The periapical tissues

Normal radiographic appearances

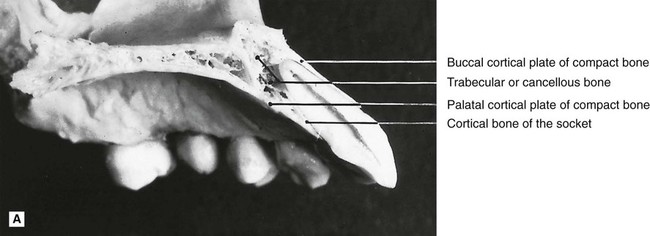

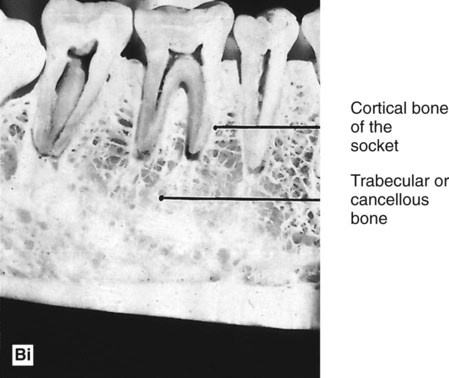

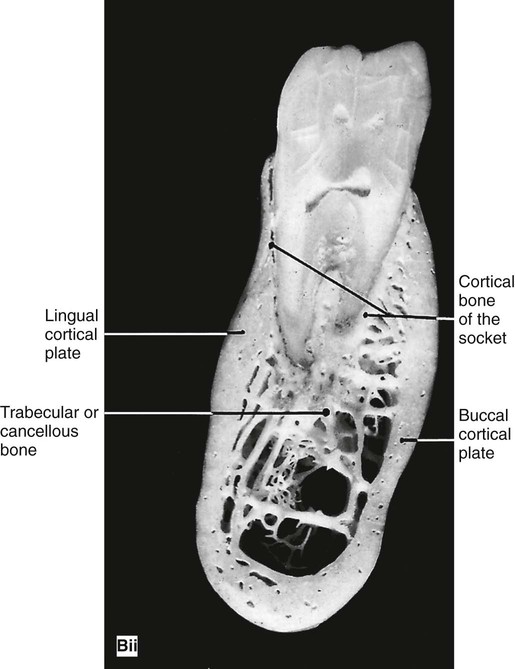

A reminder of the complex three-dimensional anatomy of the hard tissues surrounding the teeth in the maxilla and mandible, which contributes to the two-dimensional periapical radiographic image, is given in Fig. 21.1.

/>

/>

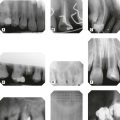

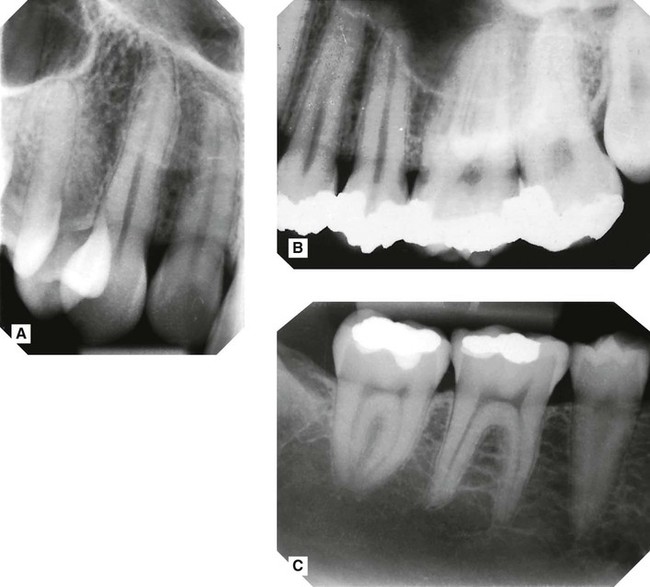

The periapical tissues of permanent teeth (Fig. 21.2)

The three most important features to observe are:

, B

, B  , C

, C  (compare with Fig. 21.1Bi) showing the normal radiographic anatomy of the periapical tissues in different parts of the jaws. Note the continuous radiolucent line of the periodontal ligament shadow and the radiopaque line of the lamina dura outlining the roots.

(compare with Fig. 21.1Bi) showing the normal radiographic anatomy of the periapical tissues in different parts of the jaws. Note the continuous radiolucent line of the periodontal ligament shadow and the radiopaque line of the lamina dura outlining the roots.• The radiolucent line that represents the periodontal ligament space and forms a thin continuous black line around the root outline

• The radiopaque line that represents the lamina dura of the bony socket and forms a thin, continuous, white line adjacent to the black line

• The trabecular pattern and density of the surrounding bone:

These features hold the key to the interpretation of periapical radiographs, since changes in their thickness, continuity and radiodensity reflect the presence of any underlying disease, as described later.

Important points to note

• There is considerable variation in the definition and pattern of these features from one patient to another and from one area of the jaws to another, owing to variation in the density, shape and thickness of the surrounding bone.

• The limitations imposed by contrast, resolution and superimposition can make radiographic identification of these features particularly difficult, hence the need for ideal viewing conditions and digital image enhancement software.

The effects of normal superimposed shadows

Radiolucent shadows

Such cavities in the alveolar bone decrease the total amount of bone that would normally contribute to the final radiographic image, with the following effects:

• The radiolucent line of the periodontal ligament may appear MORE radiolucent or widened, but will still be continuous and well demarcated

• The radiopaque line of the lamina dura may appear LESS obvious and may not be visible

• There will be an area of radiolucency in the alveolar bone at the tooth apex (see Figs 21.5 and 21.6).

Important points to note

• The fact that the radiopaque lamina dura shadow may not be visible does not mean that the bony socket margin is not present clinically. It only means that there is now not enough total bone in the path of the X-ray beam to produce a visible opaque shadow. Since the bony socket is in fact intact, it still defines the periodontal ligament space. Thus, the radiolucent line representing this space still appears continuous and well demarcated.

• Although confusing, this effect of normal anatomical radiolucent shadows on the apical tissues is very important to appreciate, so as not to mistake a normal area of radiolucency at the apex for a pathological lesion.

Radiographic appearances of periapical inflammatory changes

Types of inflammatory changes

Cardinal signs of acute inflammation

In the apical tissues, inflammatory exudate accumulates in the apical periodontal ligament space (swelling), setting up an acute apical periodontitis. The affected tooth becomes periostitic or tender to pressure (pain), and the patient avoids biting on the tooth (loss of function). Heat and redness are clinically undetectable. These signs are accompanied by destruction and resorption, often of the tooth root, and of the surrounding bone, as a periapical abscess develops, and radiographically a periapical radiolucent area becomes evident.

Hallmarks of chronic inflammation

These include the processes of destruction and healing which are going on simultaneously, as the body’s defence systems respond to, and try to confine, the spread of the infection. In the apical tissues, a periapical granuloma forms at the apex and dense bone is laid down around the area of resorption. Radiographically, the apical radiolucent area becomes circumscribed and surrounded by dense sclerotic bone. Occasionally, under these conditions of chronic inflammation, the epithelial cell rests of Malassez are stimulated to proliferate and form an inflammatory periapical radicular cyst (see Ch. 26) or there is an acute exacerbation producing another abscess (the so-called phoenix abscess).

The result is a wide spectrum of events ranging from a very rapidly spreading acute periapical abscess to a very slowly progressing chronic periapical granuloma or cyst. This variation in the underlying disease processes is mirrored radiographically, although it is often not possible to differentiate between an abscess, granuloma or cyst.

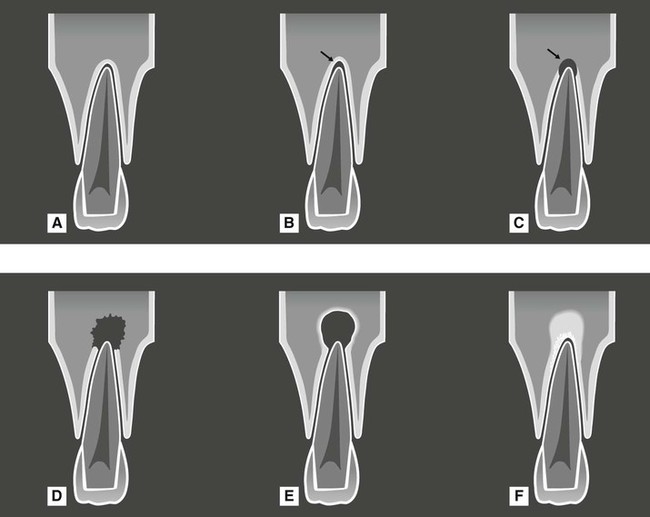

A summary of the different inflammatory effects and the resultant radiographic appearances is shown in Table 21.1. The effects are shown diagrammatically in Fig. 21.8. Various examples are shown in Figs 21.9–21.12.

Table 21.1

| State of inflammation | Underlying inflammatory changes | Radiographic appearances |

| Initial acute inflammation | Inflammatory exudate accumulates in the apical periodontal ligament space – acute apical periodontitis | Widening of the radiolucent line of the periodontal ligament space OR No apparent changes evident |

| Initial spread of inflammation | Resorption and destruction of the apical bony socket – periapical abscess | Loss of the radiopaque line of the lamina dura at the apex |

| Further spread of inflammation | Further resorption and destruction of the apical alveolar bone | Area of bone loss at the tooth apex |

| Initial low-grade chronic inflammation | Minimal destruction of the apical bone The body’s defence systems lay down dense bone in the apical region | No apparent bone destruction but dense sclerotic bone evident around the tooth apex (sclerosing osteitis) |

| Latter stages of chronic inflammation | Apical bone is resorbed and destroyed and dense bone is laid down around the area of resorption – periapical granuloma or radicular cyst | Circumscribed, well-defined radiolucent area of bone loss at the apex, surrounded by dense sclerotic bone |

/>

/> />

/>

resulting in a predominantly radiopaque sclerotic appearance (arrowed). B Long-standing low grade chronic infection associated with

resulting in a predominantly radiopaque sclerotic appearance (arrowed). B Long-standing low grade chronic infection associated with  resulting in a radiolucent periapical granuloma (white arrow), surrounded by florid opaque sclerosing osteitis (black arrow). C Well-defined area of bone destruction associated with

resulting in a radiolucent periapical granuloma (white arrow), surrounded by florid opaque sclerosing osteitis (black arrow). C Well-defined area of bone destruction associated with  which has resulted in remodelling of the antral floor, producing the so-called antral halo appearance (black arrow) (see also Fig. 28.5C).

which has resulted in remodelling of the antral floor, producing the so-called antral halo appearance (black arrow) (see also Fig. 28.5C).

Treatment and radiographic follow-up

• Repeat conventional endodontics

• Surgical exploration, curettage of the infected area and/or enucleation of the cyst (if present), apicectomy and retrograde root filling

The main recommendations of the Faculty of General Dental Practice (UK)’s 2013 Selection Criteria for Dental Radiography booklet regarding imaging the periapical tissues in relation to endodontics are summarised in Table 21.2.

Table 21.2

| Recommendation | Evidence-based Grading* |

| A good quality pre-operative paralleling technique periapical radiograph is essential for the diagnosis of endodontic problems | B |

| At least one good quality paralleling technique periapical radiograph is necessary to confirm working length(s) | B |

| If there are any doubts about the integrity of the apical constriction or resistance taper of the prepared root canal, a mid-fill periapical radiograph should be taken to confirm the position of the root filling before final compaction is carried out | C |

| At least one post-operative radiograph is necessary to assess the success of the obturation, and to act as a baseline for assessment of apical disease or healing | B |

| A further good quality follow-up paralleling technique periapical radiograph should be taken at one year after completion of treatment (see Fig 21.13) | B |

| A good quality paralleling technique periapical baseline radiograph is essential in treatment planning in vital pulp procedures | C |

| A good quality paralleling technique periapical baseline radiograph is essential for the management of minor dental trauma | C |

| Post-trauma follow-up radiographs should be taken 6 months after treatment, and then annually until root formation is complete | C |

| While expert opinion supports the taking of review radiographs, there is no evidence to support any particular frequency or duration of review | C |

| CBCT is not indicated as a standard method for the demonstration of root canal anatomy but small volume, high resolution CBCT may be indicated in selected cases | C |

*Evidence-based grading B = based on evidence from well conducted clinical studies but with no specific in vitro validation studies; C = based on evidence from expert committee reports or opinions and/or clinical experience of respected authorities and indicates an absence of directly applicable studies of good quality.

Other important causes of periapical radiolucency

Many of the conditions described in Chapters 26 and 27 can present occasionally in the apical region of the alveolar bone. Some can simulate the simple inflammatory changes described above, including:

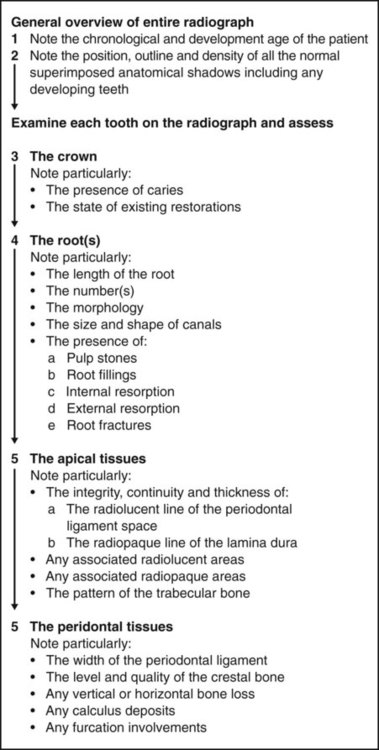

Suggested guidelines for interpreting periapical images

Overall critical assessment

A typical series of questions that should be asked about the quality of a periapical radiographic image based on the ideal quality criteria described in Chapter 9 include:

Systematic viewing

A systematic approach to viewing periapical radiographs is shown in Fig. 21.15. This approach ensures that all areas of the image are observed and that the important features of the tooth apex are examined.

To access the self assessment questions for this chapter please go to www.whaitesessentialsdentalradiography.com

in a 4-year-old, showing normal periapical tissues. Note the confusing shadows created by the radiopaque crowns and radiolucent crypts (arrowed) of the developing permanent incisors.

in a 4-year-old, showing normal periapical tissues. Note the confusing shadows created by the radiopaque crowns and radiolucent crypts (arrowed) of the developing permanent incisors.

, B

, B  . Note the circumscribed areas of radiolucency of the radicular papillae (arrowed) and the funnel-shaped roots.

. Note the circumscribed areas of radiolucency of the radicular papillae (arrowed) and the funnel-shaped roots.

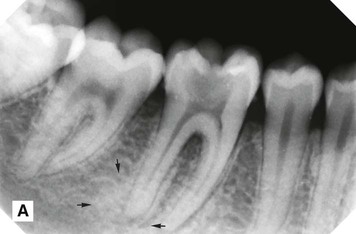

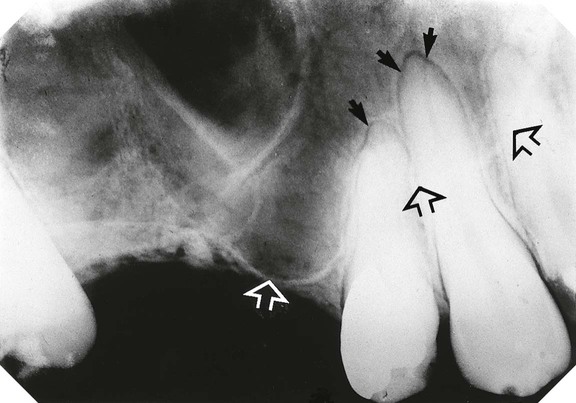

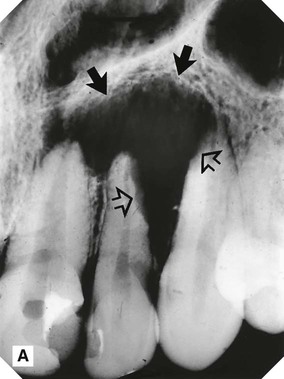

showing normal healthy apical tissues but with the radiolucent shadow of the antrum superimposed (the antral floor is indicated by the open arrows). As a result the radiolucent line of the periodontal ligament appears widened and more obvious around the apices of the canine and premolar, but it is still well demarcated, while the radiopaque line of the lamina dura is almost invisible (solid arrows).

showing normal healthy apical tissues but with the radiolucent shadow of the antrum superimposed (the antral floor is indicated by the open arrows). As a result the radiolucent line of the periodontal ligament appears widened and more obvious around the apices of the canine and premolar, but it is still well demarcated, while the radiopaque line of the lamina dura is almost invisible (solid arrows).

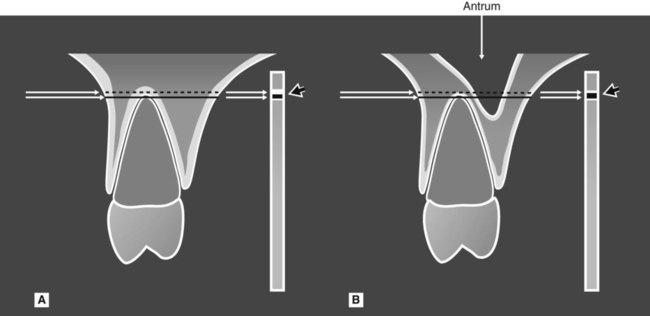

showing the anatomical tissues that the X-ray beam passes through to reach the film. A Without a normal anatomical cavity superimposed. B With the antral cavity in the path of the X-ray beam. The different resultant radiopaque (white) and radiolucent (black) lines of the apical lamina dura and periodontal ligament are shown on the film (arrowed).

showing the anatomical tissues that the X-ray beam passes through to reach the film. A Without a normal anatomical cavity superimposed. B With the antral cavity in the path of the X-ray beam. The different resultant radiopaque (white) and radiolucent (black) lines of the apical lamina dura and periodontal ligament are shown on the film (arrowed).

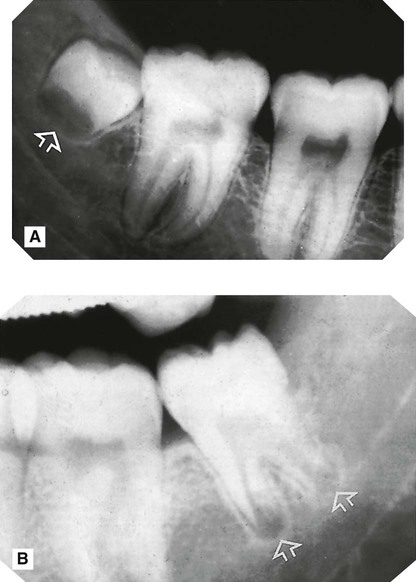

showing the radiopaque line of the mylohyoid ridge (arrowed) superimposed over the apices. B Periapical of

showing the radiopaque line of the mylohyoid ridge (arrowed) superimposed over the apices. B Periapical of  showing the radiopaque shadow of the zygomatic buttress (arrowed) overlying and obscuring the apical tissues of the molars.

showing the radiopaque shadow of the zygomatic buttress (arrowed) overlying and obscuring the apical tissues of the molars.

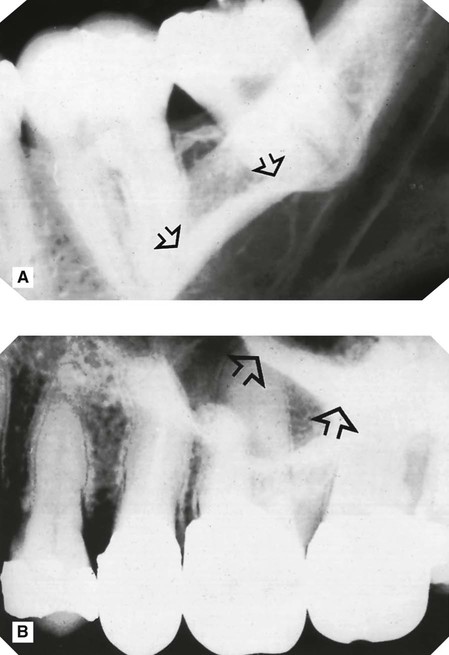

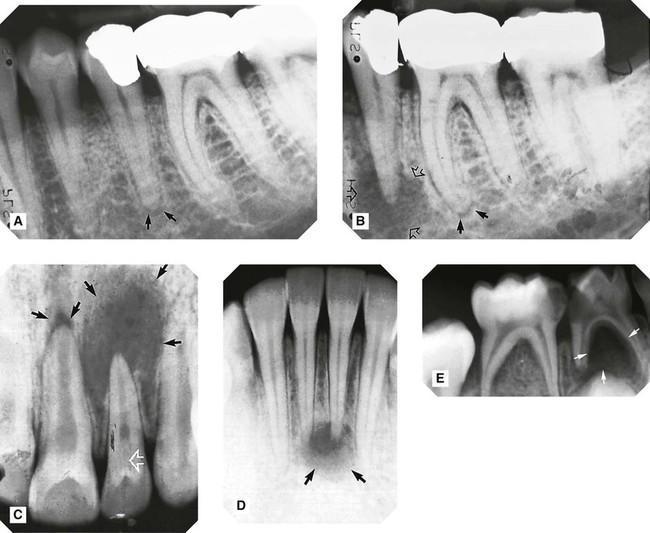

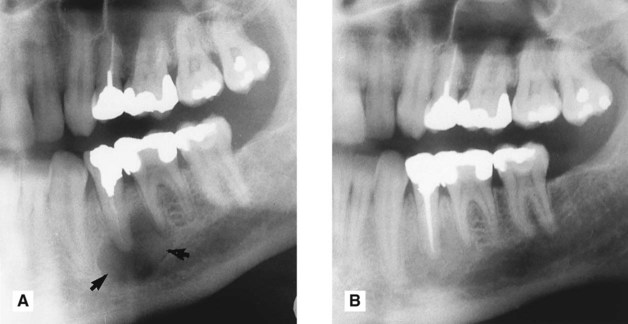

showing widening of the periodontal ligament space and thinning of the lamina dura (acute apical periodontitis) (arrowed). B Same patient 6 months later – the area of bone destruction at the apex

showing widening of the periodontal ligament space and thinning of the lamina dura (acute apical periodontitis) (arrowed). B Same patient 6 months later – the area of bone destruction at the apex  has increased considerably (open arrows) and there is now early apical change associated with the mesial root

has increased considerably (open arrows) and there is now early apical change associated with the mesial root  (solid arrows). C Large, diffuse area of bone destruction associated with

(solid arrows). C Large, diffuse area of bone destruction associated with  and a smaller area associated with

and a smaller area associated with  (black arrows) (periapical abscess).

(black arrows) (periapical abscess).  shows evidence of a dens-in-dente (invaginated odontome) (open white arrow). D Reasonably well-defined area of bone destruction (arrowed) associated with

shows evidence of a dens-in-dente (invaginated odontome) (open white arrow). D Reasonably well-defined area of bone destruction (arrowed) associated with  (periapical abscess, granuloma or cyst). E Large area of bone destruction associated with

(periapical abscess, granuloma or cyst). E Large area of bone destruction associated with  (periapical abscess). Note: with deciduous molars bone destruction is typically intra-radicular (arrowed) rather than around the apices.

(periapical abscess). Note: with deciduous molars bone destruction is typically intra-radicular (arrowed) rather than around the apices.

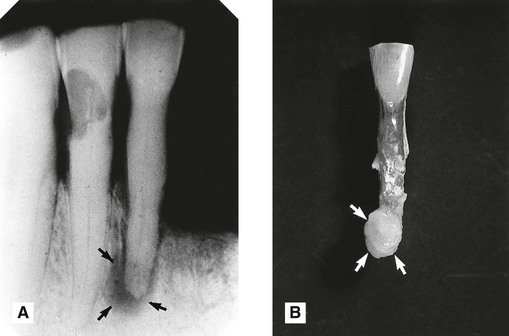

(arrowed). The surrounding bone is relatively dense and opaque, suggesting a chronic periapical granuloma or radicular cyst. B The extracted

(arrowed). The surrounding bone is relatively dense and opaque, suggesting a chronic periapical granuloma or radicular cyst. B The extracted  , showing the granuloma attached to the root apex (arrowed).

, showing the granuloma attached to the root apex (arrowed).

and B inflammatory radicular cyst (arrowed) associated with

and B inflammatory radicular cyst (arrowed) associated with  . The antrum has been displaced by the upper margin of the cyst, which is not evident on this radiograph.

. The antrum has been displaced by the upper margin of the cyst, which is not evident on this radiograph.

. B Same patient 12 months later following successful root filling at

. B Same patient 12 months later following successful root filling at  . Note the bony fill-in in the apical area.

. Note the bony fill-in in the apical area. />

/>

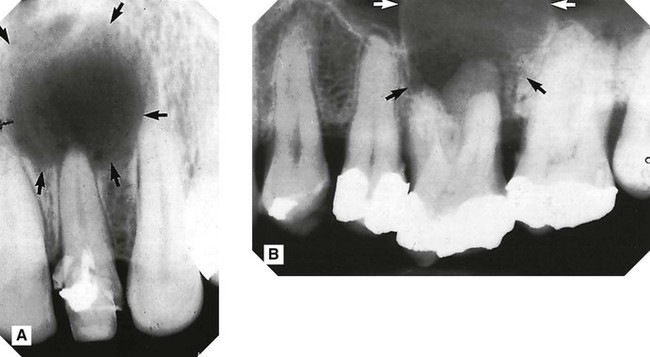

. Features of concern are the ragged bone margin (solid arrows) and the extensive resorption of

. Features of concern are the ragged bone margin (solid arrows) and the extensive resorption of  and

and  (open arrows). Initial treatment involved unsuccessful root treatment of

(open arrows). Initial treatment involved unsuccessful root treatment of  . Biopsy revealed an osteosarcoma. B Part of a panoramic radiograph showing a large poorly defined area of radiolucency in

. Biopsy revealed an osteosarcoma. B Part of a panoramic radiograph showing a large poorly defined area of radiolucency in  region (arrowed). Both premolars were caries-free and unrestored, but mobile.

region (arrowed). Both premolars were caries-free and unrestored, but mobile.  was extracted and histopathology revealed a secondary metastatic malignant tumour from a breast primary.

was extracted and histopathology revealed a secondary metastatic malignant tumour from a breast primary.