Chapter 9 The Pelvis and Sacrum

Anatomy

The bony pelvis is formed by the innominate bones, the sacrum, and the coccyx. Each hip (innominate) bone is composed of three elements: the ischium, the ilium, and the pubis. These three components meet at the acetabulum and are united by the triradiate cartilage until the age of 16 years, when fusion takes place. The sacrum is composed of five vertebrae, and the coccyx usually consists of four. The coccyx and sacrum are situated more posteriorly in women than in men and thus are more exposed to trauma. Very little motion occurs at the sacroiliac (SI) and interpubic joints because of strong ligamentous structures at these areas. Some motion occurs at the sacrococcygeal joint, but little is present between coccygeal segments.

Roentgenographic Anatomy

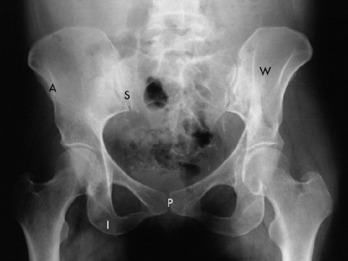

The pelvis can be well visualized by a routine anteroposterior roentgenogram (Fig. 9-1). In addition, the sacrum and coccyx may be studied by lateral views and anteroposterior views angled 15 degrees cephalad and caudad.

Osteitis Pubis

CLINICAL FEATURES

The onset is gradual, with symptoms developing a few days after the traumatic event. Pain and tenderness over the symphysis pubis are usually present. Coughing may aggravate the pain, which radiates along the adductor and rectus abdominis muscles. Stretching these muscles may reproduce the pain. Symptoms may be unilateral or bilateral. Radiation to the groin, scrotum, or perineal area is common. Examination reveals local tenderness over the symphysis pubis and adjacent soft tissue. Passive abduction of the hips and active adduction of the hips against resistance are painful.

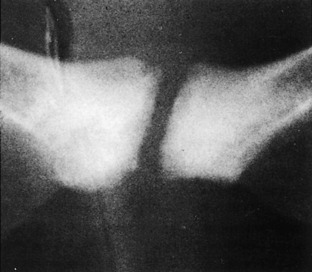

Roentgenograms of the pelvis taken early in the disease course may be normal. Later, variable amounts of spotty demineralization, widening of the symphysis pubis, and sclerosis may be noted (Fig. 9-2). Bone scanning is often positive. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also valuable. Reossification occurs over several months.

Disorders of the Sacroiliac Joint

OSTEITIS CONDENSANS ILII

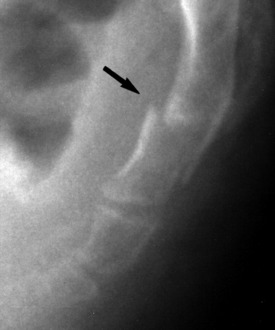

This is a lesion of unknown etiology in which bilateral sclerosis of a fairly large area of ilium adjacent to the SI joint occurs (Fig. 9-3). It is most common in multiparous women. Its importance lies in distinguishing it from ankylosing spondylitis (Marie–Strümpell disease). Ankylosing spondylitis is usually associated with an increase in the sedimentation rate and roentgenographic involvement on both sides of the SI joint. Ankylosing spondylitis also occurs primarily in men and is associated with pain. However, there is disagreement as to whether osteitis condensans ilii is ever a painful condition, and it is usually considered to be an incidental radiographic finding. It may be associated with similar lesions in the pubic bones near the symphysis pubis like those seen in osteitis pubis.

SACROILITIS

Bilateral sacroilitis occurs in conjunction with a group of diseases called seronegative spondyloarthropathies (see Chapter 8). The SI joints are involved early in the course of these diseases. The HLA-B27 antigen is usually present in these disorders, which often involve the spinal joints as well.

DEGENERATIVE JOINT DISEASE

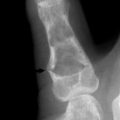

Symptomatic involvement of these joints by osteoarthritis is unusual. Even when findings are present roentgenographically, symptoms may be minimal or absent completely (Fig. 9-4). Treatment is symptomatic in these rare cases; surgery is almost never recommended, partly because of the difficulty in the diagnosis. Therapeutic steroid injections may be tried but usually require the inconvenience of fluoroscopic guidance.

Disorders of the Sacrococcygeal Region

CLINICAL FEATURES

Pain on sitting is the most common complaint. This pain is aggravated by slumping, sitting on a hard seat, or activity. Many symptoms begin with an injury and may be aggravated by constipation or rectal disease. The symptoms are more common in women. Local pain and tenderness at the sacrococcygeal joint and adjacent soft tissues are common physical findings. A rectal examination should always be performed and often reveals pain on sacrococcygeal motion. This pain often radiates into the buttocks.

Depending on the history, the roentgenogram may occasionally reveal recent injury or degenerative arthritis. Fractures, when they occur, usually involve the lower part of the sacrum or first sacrococcygeal segment (Fig. 9-5). Osteoarthritis may be noted at the sacrococcygeal joint. The alignment or configuration of the sacrum or coccygeal segments visualized roentgenographically seems to have little importance in coccygodynia.

Back and Pelvic Pain in Pregnancy

A vascular cause for back pain has also been theorized. It is known that the relaxed gravid uterus can compress the aorta and vena cava. It is also known that venous return is increased at night when the dependent edema of the lower extremities returns to the vascular space at rest with the legs elevated. This could lead to some compromise of the circulation to the lumbar neural elements and produce the back and leg pain with cramping seen at night during some pregnancies.

PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

Fractures of the Pelvis

The pelvic ring is essentially a rigid circle with very little motion at the interpubic or sacroiliac areas. Fractures involving the ring are generally classified as stable or unstable (see Chapter 16). Stable fractures are those in which the ring is completely broken only at one point (for example, superior and inferior pubic ramus fractures on the same side). With unstable fractures, the ring is broken in two or more areas (for example, both pubic rami on the same side plus an SI dislocation). Stable fractures commonly result from low energy minor falls, especially in elderly, osteoporotic females. These fractures may be treated symptomatically with a short period (1 to 2 days) of rest followed by ambulation and weight bearing as tolerated, usually with a walker.

Unstable fractures (Fig. 9-6) are often serious and potentially life threatening. They may be accompanied by genitourinary or other visceral injuries. Posterior fractures in particular may damage the adjacent venous and arterial system and produce massive retroperitoneal bleeding. The initial care is therefore directed at general stabilization of the patient. The fracture usually requires prolonged immobilization and occasionally surgical repair.

Fractures of the acetabulum occasionally involve the main weight-bearing surface of the hip joint (Fig. 9-7). Reduction, either surgically or by traction on the femur, may be needed to restore a smooth surface and prevent the development of traumatic arthritis.

PELVIC INSUFFICIENCY FRACTURES

This injury is a type of stress fracture that almost exclusively occurs in older females. Stress fractures can be of two types: fatigue and insufficiency. Fatigue fractures develop when unusually high stress is applied to a normal bone. Insufficiency fractures occur in weak bone undergoing normal stress. Osteoporosis is the usual predisposing cause, but inactivity, long-term steroid use, and other types of metabolic bone disease may also play a role. The usual sites of fracture are the pubic bones, ilium, and sacrum (Fig. 9-8). Because there is usually no history of trauma, the injury is often overlooked or misinterpreted as metastatic disease. Multiple areas may even be involved. (Compression fractures of the vertebrae and femoral neck fractures may act in a similar fashion but are generally easier to recognize.)

ROENTGENOGRAPHIC FINDINGS

Bone scanning is extremely sensitive for this injury as well as other similar conditions. Fractures may be detected as early as 3 days after the onset. (Scans may also remain slightly positive for 1 to 2 years.) Computed tomographic evaluation will usually allow differentiation from metastatic disease. MRI is also valuable in defining the lesion and differentiating it from tumor or sacroiliac joint disease.

Curtis P. In search of the ‘back mouse’. J Fam Pract. 1993;36:657-659.

Dittrich RJ. Coccygodynia as referred pain. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1951;33-A:715-718.

Dreyfuss P, Dreyer SJ, Cole A, et al. Sacroiliac joint pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12:255-265.

Howorth B. The painful coccyx. Clin Orthop. 1959;14:145.

Macnab I. Backache. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1977.

Ramsey ML, Toohey JS, Neidre A, et al. Coccygodynia: treatment. Orthopedics. 2003;26:403-405.

Resnik CS, Resnik D. Radiology of disorders of the sacroiliac joints. JAMA. 1985;253:2863-2865.

Rungee JL. Low back pain during pregnancy. Orthopedics. 1993;16:1339-1344.