Chapter 21

The Pediatric Patient1

Children are not like men or women; they are almost as different creatures, in many respects, as if they never were to be the one or the other; they are as unlike as buds are unlike flowers, and almost as blossoms are unlike fruits.

Walter Savage Landor (1775–1864)

General Considerations

Since the late 1920s, awareness of the importance of child health care has increased. Along with better control of infectious disease and great strides in nutrition and technology has come the recognition of the importance of the behavioral and social aspects of a child’s health. Despite the many advances and the marked reduction in infant mortality rates, the neonatal period remains a time of very high risk.2

In 2004, a total of 27,936 deaths occurred in the United States in children younger than 1 year, an infant mortality rate of 6.8 per 1000 live births; 70% of these deaths occurred in the first month after birth, almost all of those in the first week.3 Although the infant mortality rate reached a record low level of 6.14 infant deaths per 1000 live births in 2010,4 the United States still ranks poorly in this regard when compared with other industrialized countries.5

Unintentional injury and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) are the leading causes of infant mortality after the first month of life. SIDS is the leading cause of death among infants aged 1 to 12 months and is the third leading cause overall of infant mortality in the United States. Although the overall rate of SIDS in the United States has declined by more than 50% since 1990, thanks to the “Back to Sleep” campaign, rates have declined less among non-Hispanic African-American, and American Indian/Alaska Native infants. SIDS is defined as the sudden death of a healthy infant younger than 1 year that cannot be explained after a thorough investigation is conducted, including a complete autopsy, examination of the death scene, and review of the clinical history. Preventing SIDS remains an important public health priority. Several risk factors have been associated with SIDS, including prone sleeping, sleeping on soft surfaces, loose bedding, overheating as a result of overdressing, smoking in the home, maternal smoking during pregnancy, bed sharing, and prematurity or low birth weight. In some cases, SIDS seems to be caused by a mutation in a gene that leads to a cardiac channelopathy, resulting in prolonged QT interval and other arrhythmogenic states.

Unintentional injury remains the top killer of children aged 1 to 14 years6 ahead of cancer and birth defects. More than 5300 children in the United States died in 2004 from unintentional injuries—an average of 15 children each day. Motor vehicle occupant injury is the leading cause of injury-related death among all children after infancy. Death from airway obstruction is the leading cause of injury death for children younger than 1 year, and drowning follows motor vehicle injuries for children aged 1 to 14 years. Poverty is the primary predictor of fatal injury; male sex and race are additional factors. Native American and African-American children are the groups at highest risk; they are approximately twice as susceptible to fatal injury as are white children.

Previous chapters discussed the history and physical examination as they relate to adult patients. This chapter discusses the differences related to physical diagnosis in the pediatric age group. The field of pediatrics is broad and encompasses birth through adolescence, often defined as up to age 22. During this period, there are enormous changes in children’s emotional, social, cognitive, and physical development, all of which must be discussed thoroughly.

This chapter is organized somewhat differently from the previous chapters. The first section is devoted to the pediatric history, which is similar in most pediatric age groups but differs in important ways from the adult history. The sections that follow are devoted to the physical examinations of the following age groups:

• Neonatal period (birth to 1 month of age)

• Infancy (1 month to 1 year of age)

• Toddler and early childhood (1 to 5 years of age)

Most of this chapter is devoted to the first three groups because the order and techniques of examining children 6 to 22 years of age are similar to those for adults. You will note, however, that the order of the physical examination does differ from that of the adult in the younger age groups.

The reader is advised to watch the video presentation on Student Consult to review the physical examinations of the newborn and the toddler, as well as specific pointers about the neurologic assessment at these ages. The internet version also contains a demonstration of an adolescent history with a standardized patient.

The Pediatric History

The pediatric history, like the adult history, is obtained before the examination is performed. During this period, the child can get accustomed to the clinician. Unlike the adult history, however, much of the pediatric history is taken from the parent or guardian. But it can be helpful to include the child in the process. If the child is old enough, interview him or her as well.

Effective communication with the child is the key to a successful workup, just as with an adult. An infant communicates by crying and, in so doing, indicates the existence of an unmet need. Although older children can communicate through language, they also often use crying as a response to pain or to express emotional unrest. This mode of communication merits attention. Newborns can also communicate by cooing and babbling, which indicates contentment.

In infancy, children use sounds to mimic words, as well as using gestures to communicate. At approximately 10 to 12 months of age, children usually speak their first word, usually “dada” or “mama.” By 15 months of age, children are expected to say between 3 and 10 words, and by 2 years of age, their vocabulary may contain more than 200 words; it is at this age that we expect children to be able to put 2 or more words together in a phrase, such as “Juice gone” or “Up me!” By 3 years of age, children are able to put together sentences of 5 or 6 words from a 1500-word vocabulary, and should be 50% intelligible to an adult who does not know the child. By the time they are 6 years of age, they are able to communicate in longer sentences, with a vocabulary of several thousand words, and use most of the grammar of their native language. Three-year-olds can give the clinician a good idea of what hurts, where, and how it feels. The 6-year-old can give some idea of how and when the complaint started. The examiner must pay attention to everything the child says because the words used may give insight into the child’s physical, emotional, and developmental state, as well as his or her home situation and other factors in his or her environment.

An effective relationship with a child begins by engaging with him or her. Start by admiring the child’s shoes or toy; possessions are more neutral topics for the child to talk about at first than his or her own body or behavior. One of the best ways to make a child feel comfortable is through praise. When talking to a child, it is useful to say, “Thank you for holding still. That makes the examination easier.” The use of “You’re a good boy” or “You are such a sweet girl” may produce embarrassment. Therefore praise should be given for a child’s behavior or actions and not for his or her personality. Sharing a book with the child (e.g., as part of the “Reach Out and Read” program7) is another useful way to engage the toddler or preschooler. Particularly for this age group, some examiners may choose not to wear a white coat to alleviate some of the child’s fears.

It is important not to talk down to children. The examiner must assess the developmental level of the child and choose words that are appropriate to that child’s level of understanding. This is especially important in dealing with a preadolescent; in fact, when interviewing such a child, the interviewer may gain more cooperation from the child by treating him or her as a bit older than his or her actual age, rather than younger.

Although most of the history is obtained from the parent or guardian, some questions are asked of the child. There are two simple rules in asking questions of children:

Interviewers are often amazed by how well a child can respond to questions phrased according to these rules. School-aged children can respond to structured, open-ended questions. Asking “How do you like school?” may elicit only a shrug. Asking “What do you like best about school?” is likely to get the child talking. It is useful to spend time observing the child at play while interviewing a parent. It is also rewarding to allow a toddler to play with a stethoscope, tongue blade, or penlight to “make friends” with the equipment that will be used later in the physical examination.

The pediatric history consists of the following:

The chief complaint and the history of the present illness are obtained in the same manner as with the adult patient. The history should identify the informant, and the interviewer should try to establish whether and where the child has a regular source of medical care. The history of the present illness should always include information about the effect of an acute illness on the child’s oral intake, activity level, hydration status, and ability to sleep. For a chronic problem, the examiner should look for effects on the child’s growth and development.

Birth History

The past medical history section begins with the birth history. An opening with the mother such as “How was your pregnancy?” may be all that is needed to start this part of the medical history. Determine any maternal problems, medications taken, illnesses, bleeding, whether x-ray films were taken during the pregnancy, and whether the child was born “on time.” Ask the following questions:

“How old were you at the time of your child’s delivery? How old was the baby’s father?”

“How many times have you been pregnant? Have you had any miscarriages or children who died in infancy?” If yes, “Do you know the cause? Were any of your children born too early?” (Box 21-1 contains an explanation of the shorthand notation for this information.)

Although testing for human immunodeficiency virus infection is not automatic, most women also accept it because therapy with antiretroviral drugs in the last trimester can reduce rates of congenital infection from 25% to less than 2%.

“How long was your labor? Were there any unusual problems with it?”

“What type of delivery did you have, vaginal or cesarean?” If cesarean, ask for the reason. Was it because of a previous cesarean birth or a problem related to this pregnancy?8

“Did the baby come out head first or feet first?”

“Were you told of any abnormalities at birth?”

“Were you told the Apgar9 scores?” If the parents don’t know, ask, “Did he cry right away? Or did the doctors need to do something to help him start breathing?”

“Did the child experience any problems in the newborn nursery, such as breathing difficulties? Jaundice? Feeding problems?”

“Did the child receive oxygen in the nursery? Antibiotics? Phototherapy?”

“After delivery, how long did the baby remain in the hospital?”

“Did the child go home with you?” If not, ask what the reason was.

“Were you told that problems were found on the newborn screening tests?”10 If yes, “What were they? Was follow-up testing performed?”

Note the order of these questions: they begin with the prenatal course, then focus on the actual birth, and then turn to the postnatal course. See the sample write-up of a newborn’s history at the end of this chapter. The amount of detail needed in the birth history depends on the age of the child and the clinical situation. Most of this information is pertinent for an infant; for a teenager, it is probably enough to know whether the child was born full term and whether there were any problems in the neonatal period.

In recent years, many babies are being born following methods of conception and delivery that were unavailable in the past. Babies might be adopted; they can be conceived via in vitro fertilization; conception may have occurred by artificial insemination using sperm provided by the rearing father or by a donor; a donor egg might have been used; the pregnancy might have been carried in the womb of the rearing mother or of a maternal surrogate. Gathering this information is important for different reasons: psychologically and emotionally, it is important to support the parents who are raising the child, regardless of whether they are the biological parents. However, genetically, it is important to obtain information about the biological parents to assess the child’s susceptibility to inherited disease. Interviews to explore inherited disorders need to be conducted with considerable tact. The parents may not want to discuss this family history in front of the child, and each parent should be offered a private interview.

Past Medical History

As with the adult, the past medical history should include details of any hospitalizations, injuries, and surgeries, as well as any medications taken on a regular basis. Ask, “Does your child have any chronic health problems?” Common chronic health problems in children include asthma, seizure disorders, eczema, recurrent ear infections or urinary tract infections, sickle cell disease, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and cerebral palsy. If the child was born before term, ask about late effects of preterm birth, such as chronic lung disease, nutritional problems, developmental and motor difficulties, and sensory deficits.

It is important to identify allergies to medication (including penicillin), foods, or other substances. The most common problem associated with medications is the development of a rash. Rashes, however, are common in children and may have occurred coincidentally at the time a medication was prescribed. Therefore try to determine whether the medication was the cause of the rash. Certain viral states “sensitize” a patient to a medication. The medication may be given at other times without any problems. Whenever a parent describes a “medication allergy,” ask the following questions:

“How do you know the child is allergic to …?”

“What was the rash like?” A hivelike or urticarial rash is likely to be a true allergy.

“Did the child have any problems other than the rash?”

“How long after the child started the medication11 did the rash appear?”

“After the medication was stopped, how long did the rash last?”

“Has the child ever taken the medication again with recurrence of the rash?”

Nutrition

Nutrition is central to the child’s well-being. Obesity in childhood is considered by some to be an epidemic in this country. In 2009–2010, 16.9% of U.S. children and adolescents or 12.5 million children and adolescents were obese.12

Parents need to be proactive in preventing their children from becoming obese by feeding them healthy foods and teaching them how to make healthy food choices for later on as older children and adults. Getting a complete nutritional history not only helps you monitor the child’s nutritional health, but may also help you make the diagnosis of an acute problem. Ask the following questions:

For infants:

“How many ounces of formula13 is the baby given a day? What kind of formula do you feed? How do you prepare it?”

“When did you introduce solid foods, such as cereals?”

“Has the child ever had a problem with vomiting? Diarrhea? Constipation? Colic?”

For infants, differentiate diarrhea from normal liquid stools. If the child is breast-fed, the stools are usually a yellow or mustard-colored liquid and may follow each feeding. If the child is formula-fed, the stools are more likely to be yellowish-tan and firmer. Infants frequently have green, brown, or grayish stools, and normal stools may be loose or liquid in consistency. With diarrhea, the stools are more frequent and all liquid, and watery rings stain the infant’s diaper. Minor changes in the stool are common. Normal infants may have several bowel movements a day but may go 1 or more days without a bowel movement. Small, hard, pebble-like stools indicate constipation.

Until an infant is 1 year of age, breast milk or infant formula should be his or her main food. Cow’s milk may be fine for older children, but it may irritate the infant’s digestive system, which is not fully developed. There are some major differences between cow’s milk and breast milk or formula: Cow’s milk has too much protein and sodium and too little iron, vitamin C, copper, and zinc for a developing infant. For a toddler or older child, determine how many ounces of milk and juice the child drinks. Inquire about the daily consumption of vegetables, fruit, protein, and especially “junk foods.” Does the child take a vitamin supplement? It is also valuable to ask about the meal pattern: Does he or she eat breakfast, lunch, dinner, and healthy snacks? Where does he or she eat? With whom? Do you eat any meals together as a family? Older children and adolescents eat many meals away from home; such patients are your best source of information about their eating patterns.

Growth and Development

Ask about the child’s pattern of growth. As is discussed later, the height, weight, and head circumference of children should be plotted on appropriate growth curves. Has the child’s growth been consistent, or has he or she crossed percentile lines on the growth chart? Is the mother concerned about her child’s growth?

Ask, “How has the child been growing? Are you concerned about his or her weight gain or about his or her linear growth?” Asking about how quickly the child outgrows shoes and clothes may give you an indication of his or her growth rate.

The child’s characteristics or temperament during infancy may be predictive of early developmental progress and of how he or she will respond to new experiences in years to come.

Ask, “Would you describe your child as active, average, or quiet?” If this is not the mother’s first child, it is appropriate to ask how this infant compares with the family’s other children: Is this child slower, faster, or about the same in development?

“When did the child first sleep through the night?”

“Do you have any concerns about the child’s development?” If yes, “What are they?”

“Has the child ever failed to make progress or ever lost any ability he or she once had?”

“Does the child have difficulty keeping up with other children?”

After asking general questions about the child’s development, you need to get information about specific developmental milestones that reflect the child’s ability in at least four areas: gross motor, language, fine motor, and personal and social development. The following questions should be asked:

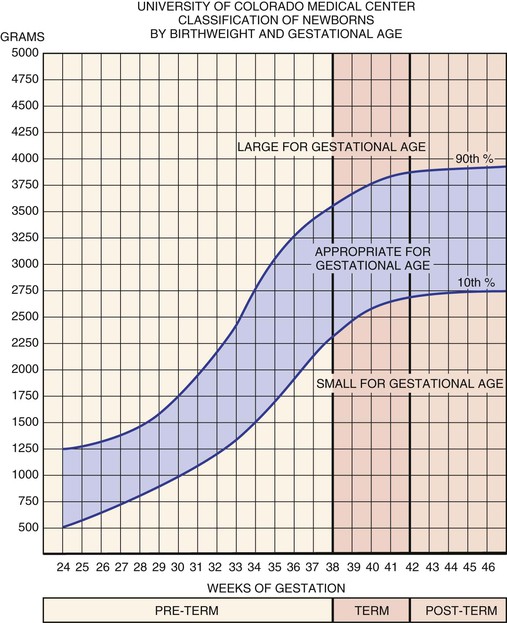

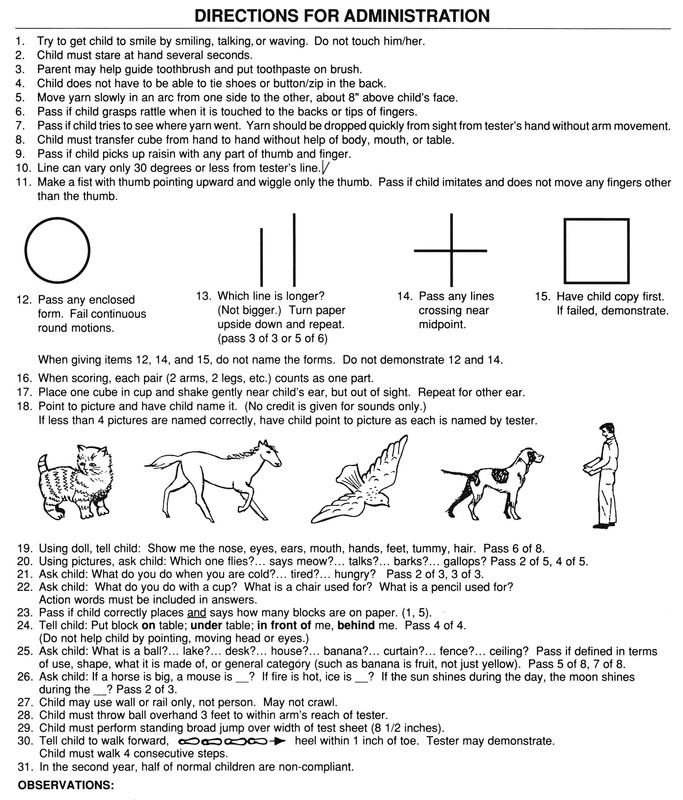

The Denver Developmental Screening Test, shown in Figure 21-1, was developed to detect developmental delays in the first 6 years of a child’s life, with special emphasis on the first 2 years. It is standardized on the basis of findings from a large group of children in the Denver, Colorado, area and tests the four main areas of development indicated previously. A line is drawn from top to bottom of the sheet according to the age of the child. Each of the milestones crossed by this line is tested. Each milestone has a bar that indicates the percentage of the “standard” population that should be able to perform this task. Failure to perform an item passed by 90% of children is significant. Two failures in any of the four main areas indicate a developmental delay. This test is a screening device for developmental delays; it is not an intelligence test.

Figure 21–1 Denver Developmental Screening Test. (Reprinted with permission from William K. Frankenburg, MD, Denver Developmental Materials, Inc. Denver, Colo.)

Another screening test, the Ages and Stages Questionnaires,14 is a series of 19 age-specific questionnaires that use parents’ responses to specific questions to assess progress in communication, gross and fine motor, problem solving and personal adaptive skills. The questionnaires, which provide a pass/fail score, are useful in children from 4 to 60 months, takes 10 to 15 minutes to administer, and were normed on more than 12,000 children from diverse ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, including Spanish speakers.

For the school-aged child, the child’s social, motor, and language development, as well as emotional maturation, are reflected in current behavior. A nice way to broach this topic is to ask, “How would you describe your child as a person?” Follow up with some or all of these questions:

“What do you enjoy the most about your child? The least?”

“Does your child usually complete what he or she starts?”

“How does your child get along with other children his or her age?”

“How many hours of sleep does your child get each night?”

“Does the child have any recurrent nightmares?”

“What type of responsibility can he or she be given?”

“How old was your child when he or she started school?”

“In what grade is he or she now?”

“How is he or she doing in school?”

“Has he or she ever been left back?”

“What is your child’s grade level for reading? Math?”

“What does your child enjoy doing during his or her free time?”

“What kinds of things scare him or her?”

“How does the child get along with his or her brothers and sisters?”

“How much time does your child spend watching TV? Playing video games? On the computer?”

It is useful to ask whether the child has any disturbing habits. This question allows the parent or guardian to vent any previously unexpressed concerns. This may be asked as follows:

In 2007, because of a striking increase in the prevalence of autism and autistic spectrum disorders, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended screening all children for the following behaviors:

Because it is clear that early intervention can significantly improve the outcome for children with autism and autistic spectrum disorders, the Academy recommends that this screening be performed at least twice during the first 2 years of life.

Immunization History

The pediatric history contains detailed information about immunizations. The current immunization schedule for persons aged 0 to 18 years of age in the United States,15 as of February 1, 2013, is shown in Appendix F.

Vaccines are one of the major successes of twentieth-century medicine; clinicians are unlikely to ever see many of the vaccine-preventable diseases such as polio, rubella, or diphtheria, and if an immunized child does have one of these diseases, that child may have an immune deficiency. However, if the child is missing one or more vaccines, you should consider the possibility the child is suffering from a vaccine-preventable illness. Note that the immunization schedule offers instructions for providing “catch-up” vaccinations for children who have fallen behind.

As the schedule of vaccines has become rather complex, many parents are unsure about the exact vaccines given to the child. Ask to see the immunization record, which many parents carry with them. Also, many localities have centralized vaccine registries where health care providers can access the record of a particular child.

You can partially reconstruct the child’s vaccine history, if necessary, with the following questions:

“Did the child get shots right after his or her first birthday? How many?”

For the child 11 or older, ask, “Has she gotten any vaccines recently? How many?” Recent additions to the vaccine schedule provide adolescents with protection against pertussis; meningococcal disease; hepatitis A; and, for both boys and girls, human papillomavirus, the leading cause of cervical cancer. Also ask, “Did your child have a reaction to any of the shots?”

For an older child, ask “Has he or she ever had chickenpox?” See “Clinicopathologic Correlations” at the end of this chapter for a detailed description of this disease.

Social and Environmental History

The social and environmental history should include the parents’ ages and occupations, as well as the current living conditions. Ask these questions:

“How many rooms do you live in?”

“Is the child cared for in any other house?”

“Who supervises the child during the day?”

“How does the family have fun together?”

“Do both the child’s parents share in family life?”

“What is the condition of the paint and plaster in your home?”

Dust and chips from deteriorating lead-based paint are the most common sources of lead exposure in young children. Although the rates and severity of pediatric lead poisoning have declined in the United States, childhood lead poisoning remains a problem throughout the world. The effects of lead poisoning are more pervasive and longer lasting in children than previously believed, and they occur at levels once thought safe. Prenatal exposure and exposure in children 2 to 3 years of age are of particular concern. In 2011, elevated blood lead levels were found in 35,000 children16 on screening blood tests. Children who are younger than 6 years, especially 1- and 2-year-olds, are at greatest risk because of normal hand-to-mouth activity. Although pica (a morbid craving to ingest nonfood substances such as chalk or coal) has been implicated in lead poisoning, children more commonly ingest lead-containing dust through normal hand-to-mouth activity. Ask the parent or guardian the following:

“Does the child live in or visit a home that was built before 1960?”

“Has any renovation been done in your home recently?”

“Does the child have a sibling, house mate, or friend with an elevated blood level of lead?”

“Has the child visited other countries for substantial periods?”

“Does the child live near a heavily traveled major highway, bridge, or elevated train?”

“Does the family use ceramic pottery from another country?”

“Does the child come in contact with an adult whose job or hobby involves exposure to lead?”

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, the child should be tested with a direct blood lead test.

Other questions related to safety in and around the home concern the presence of smoke detectors and window guards in the home, use of a crib with the child sleeping on his or her back, supervision and hot water temperature during baths, and use of car seats and bicycle helmets.

Cultural History

During the past 40 years, the United States has experienced, in absolute numbers, the biggest immigration wave in its history with more than 40 million arrivals. Unlike previous waves that were almost entirely from Europe, the modern influx has been dominated by Hispanic and Asian immigrants. These immigrants, similar to those in previous centuries, tend to have higher numbers of women of childbearing age and higher birth rates than the U.S.-born population.17

Because the United States is composed of many diverse populations, questions about culture and spirituality need to be explored to understand the unique contexts in which children and families view their health and illness. Kleinman’s explanatory model18 frames questions to elicit responses from children and families about their illnesses that are influenced by their beliefs:

1. What do you think caused (your infant’s or child’s) problem?

2. Why do you think it happened when it did?

3. What do you think (is the effect of) your (infant’s or child’s) sickness? How does it work?

4. How severe is the sickness? Will it have a short course?

5. What kind of treatment do you think (your infant or child) should receive?

6. What are the most important results you hope to receive from this treatment?

7. What are the chief problems your (infant’s or child’s) sickness has caused?

8. What do you fear most about (your infant’s or child’s) sickness?

It is imperative that the health care provider not allow his or her own beliefs to blind himself or herself to the merits in the beliefs of people of other cultures.19 The other cultures could be correct. It is all too easy to dismiss the beliefs of others, citing “the science” to support our Western medical beliefs. As you take care of all patients, remember that all medical systems are based on observed cause-and-effect relationships. The major difference with the scientific approach is that science is capable of being tested (verified or nullified) by experiment or observation. A scientific hypothesis can be proven incorrect. The beliefs of others cannot.

Family History

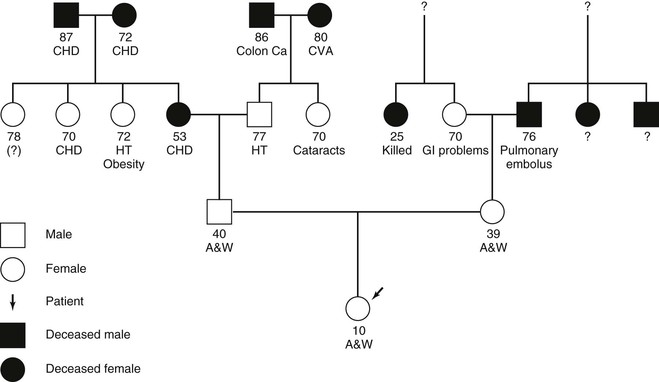

The pediatric family history is basically the same as in the adult history but may play a more significant role in identifying genetic disorders and inborn errors of metabolism. When taking the family history of a pediatric patient, it is worthwhile to construct a pedigree or genogram, a graphic representation of the family history. As illustrated in Figure 21-2, in a pedigree, boys and men are represented by squares; girls and women are represented by circles; the patient, or proband, is illustrated with an arrow; and for individuals who are deceased, the shape is black, or a line is drawn through the circle or square. Information about three generations should be obtained: that is, the child and his or her siblings; the parents and their siblings; and the grandparents. For each individual, the following information should be obtained:

• If alive, name and current age

• Any miscarriages or children who died in infancy or later

Figure 21–2 Pedigree (family tree). A&W, Alive and well; Ca, cancer; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; GI, gastrointestinal; HT, hypertension.

By analyzing the pedigree, the examiner can gain insight into the child’s risk for having specific diseases in the future. Recently, advances in assisted reproductive technology have required the addition of new pedigree symbols to designate sperm and egg donors, surrogates, etc.20

Review of Systems

The review of systems needs to be age-appropriate, and so it is described along with the approach to the physical examination in the following sections.

The Adolescent Interview

Although most adolescents are well adjusted and easy to interview, some can present a number of special challenges.

In 2005, more than 42 million residents of the United States were adolescents 10 to 19 years of age, constituting approximately 14% of the U.S. population. Three-fifths of the adolescent population was non-Hispanic white, and two-fifths consisted of other racial and ethnic groups.21 Too old to be considered children but too young to be considered adults, adolescents may avoid health care because they do not feel comfortable either at the pediatrician’s office or at an internist’s office. On the other hand, mortality rates are almost five times higher among 15- to 21-year-olds than among 5- to 14-year-olds, and adolescents experience considerable morbidity. Perhaps 20% of adolescents have a chronic health condition, and many suffer consequences of engaging in adult behaviors: sexual activity, drug and alcohol use, driving, paid employment, and competitive sports. Adolescents’ limited life experience and their psychologic stage (described as “adolescent egocentrism”) magnify the risks of these exposures. The rapid physical changes in a teenager’s body come at a time when the psychologic process of forming a body image is at its strongest; the mismatch between the actual and the desired physique can be a serious source of distress for a teenager. Major mental illness, from depression to schizophrenia, can manifest in this age range as well.

Until ages 11 to 12 years, the pediatric history is usually obtained from the child and parent together. Both sources continue to be important, but it is essential to give an adolescent private time with the doctor. In fact, laws in most states entitle adolescents to confidential care for sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy, and drug use.

Early in the visit, it is vital to establish the ground rules about confidentiality with both the parent and the teenager, as well as to support the parent’s role in their son’s or daughter’s health care. For instance, the clinician may say something like, “For someone your son’s age, it’s very important for him to have a private visit with his doctor, just as it would be for you with your doctor. I will keep what he and I talk about confidential unless something comes up that is acutely life-threatening. While it’s crucial that I keep what he tells me confidential, I also encourage my teenaged patients to share with their parents what they have told me.” Generally, during the physical examination, the parent or caretaker should be asked to leave the room, which provides an opportunity to discuss confidential matters with the adolescent privately.

“What are your responsibilities?”

“What are the rules that you have to follow?”

“Do you have brothers or sisters? How do you get along? What sort of things do you argue about?”

If the situation warrants it, you might need to ask, “Do you feel safe at home?”

For “Education,” you can ask the following questions:

If indicated, you might need to ask the following questions:

“A” stands for “activities” and “alcohol.” Some questions about activities are as follows:

“Are you involved in any clubs or sports?”

“What do you do after school?”

Asking about alcohol use broaches a potentially sensitive subject, and there are many ways to introduce it; for instance:

“Do any of your friends use alcohol? Have you ever tried it?”

“Lots of kids your age are curious about drinking. How about you?”

If the teenager does report drinking, then you need to explore how much, how often, and whether there have been negative consequences (i.e., losing consciousness, a “driving while intoxicated” offense, or a suspension from school).

“D” stands for “drugs” and “depression.” Drug use can be asked about in the same way as alcohol. Remember that nicotine and other chemicals in tobacco are drugs. Screening for depression merits special emphasis. Suicide is one of the top three causes of death among teenagers, and at least 50% of teenagers who complete suicide had visited a physician in the preceding 2 weeks. Therefore at every visit with a teenager, ask something like:

“How would you describe your mood?”

“Do you ever find yourself feeling down and sad for more than a few hours?”

If the teenager admits to a depressed mood, then you need to probe further:

Thoughts of suicide on the part of a teenager are a clear-cut indication to violate confidentiality. You must involve the parent or another responsible adult in getting the adolescent prompt mental health care.

The “S” stands for “safety” and “sex.” Safety refers not only to personal safety practices, such as using a seat belt or wearing a bike helmet, but also to the risk of violence in interpersonal relations: at home, with an intimate partner, at school, or in the community. Almost 50% of students in ninth through twelfth grades have initiated sexual activity, 6% of them before age 13.22 Half of the new cases of sexually transmitted diseases occur in people aged 15 to 24 years, and almost 1 million girls aged 15 to 19 years become pregnant each year.

There are many ways to introduce the topic of sexual activity. For instance, you can normalize the questions: “I know that lots of people your age are thinking about having sex. How about you?” It may also be very helpful to explain your “need to know”: “In order to understand what is causing your pain, I need to know something about your sexual experiences.” However or whenever you bring it up, it is useful to be explicit: Something like “Have you ever had sex?” is more likely to tell you what you need to know than “Are you sexually active?” The teenager may answer no to the second question because he or she has not had sex in 2 weeks. It is also important to consider the possibility that your patient is having sex with someone of the same gender and to phrase your questions with as little heterosexual bias as possible.

It can be challenging to maintain your composure when a teenager discloses high-risk behavior to you. You need to help the teenager appreciate the risk that he or she is incurring at the same time that you support your relationship with your patient. One way to handle this is to invite the teenager to reflect on his or her own behavior:

A large number of teenagers who are sexually promiscuous turn out to have been victims of incest or sexual abuse as children. In more than 80% of all cases of sexual abuse, the molester is not a stranger. All children should be told that their bodies are private and that no one has the right to touch them in a way that makes them feel uncomfortable. Children need to know that there are different types of touch: Good touches are hugs, kisses, and pats; confusing touch is tickling or rubbing; bad touch is hitting, hurting, spanking, or touching or fondling the “private parts” of their bodies. Listen carefully to a child who describes any type of sexual abuse. Children do not confabulate sexually explicit stories. If the clinical circumstances warrant, a child older than 3 years of age can be asked the following:

A child who has been sexually or physically abused may exhibit behavior such as aggression, moodiness, irritability, withdrawal, regression, memory loss, insecurity, and clinging. In addition, the child may exhibit some of the following physical changes: torn or bloody clothing, bruises or other suspect injuries, difficulty in walking or sitting, loss of appetite, stomach problems, genital soreness or burning sensation, difficulty in urination, vaginal or penile discharge, excessive bathing, or a desire not to bathe at all. An older child in school may exhibit a drop in academic performance, prevarication, stealing, or even running away from home.

Adolescents and even younger children now spend a great deal of time exploring the Internet, which is both a boon and a source of concern. Ask the youngster about the family’s rules about using the Internet. Specifically, ask the following:

“How much time each day do you spend online?”

“Do you have a page on Facebook or Twitter or something similar?”

The American Academy of Pediatrics has published guidelines for youngsters and families to minimize the hazards of Internet use.23

Examination of the Newborn

When examining the newborn, you are trying to answer three questions:

1. How well is this infant making the transition to extrauterine life?

2. Is there any evidence of birth trauma?

3. Does this infant have any evidence of congenital malformations?

The newborn is assessed in the delivery room immediately after birth to determine the integrity of the cardiopulmonary system. The infant is dried with a towel and placed on a warming table, where the initial examination is conducted. Gloves are worn for this initial examination because the newborn is coated with the mother’s vaginal secretions and blood.

The initial examination consists of the evaluation of five signs:

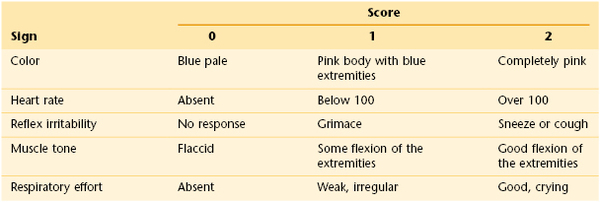

Dr. Virginia Apgar developed a scale for rating these signs 1 and 5 minutes after birth. The Apgar scale is shown in Table 21-1. Each of the signs is scored from 0 to 2. At 1 minute, a total score of 3 to 4 indicates severe cardiopulmonary depression, and the infant requires immediate resuscitative measures; a score from 5 to 6 indicates mild depression. The tests are repeated at 5 minutes; if the infant is still mild or moderately depressed at that point, a 10-minute Apgar score can also be given. A score of 8 or more indicates grossly normal findings of the cardiopulmonary examination.

Table 21–1

Apgar Scale

The acronym APGAR is useful for remembering the examinations of the Apgar test: Appearance, or color; Pulse, or heart rate; Grimace, or reflex irritability; Activity, or muscle tone; Respiratory effort.

General Assessment

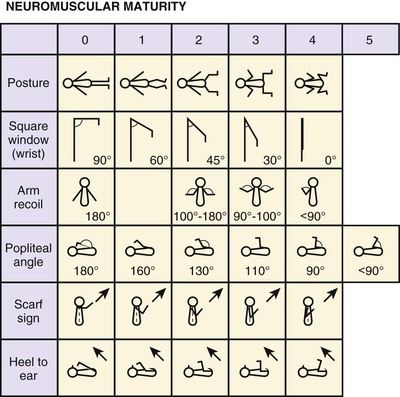

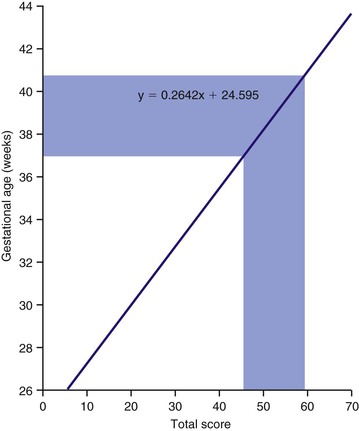

After the Apgar score has been determined, the gestational age should be assessed. Because gestational age based on menstrual dates is frequently inaccurate, it is important to make an objective determination of the gestational age, which is an indicator of the maturity of the newborn. Gestational age has important implications for the challenges of adaptation the infant will face in the coming hours and days. Experienced clinicians can make a fairly accurate assessment of gestational age in the delivery room. A more formal assessment is then performed in the nursery; it should be done in the first 24 hours after the infant’s birth. The standardized system for assessing gestational age is the Ballard clinical assessment. This is based on 10 neurologic signs and 11 external signs such as skin texture, breast size, and genital development. The neurologic scoring system is shown in Figure 21-3, and the external criteria are shown in Table 21-2.

Figure 21–3 Ballard clinical assessment. Following are some notes on techniques for assessing the neurologic criteria: Posture: Observed with infant quiet and in supine position. Score 0, arms and legs extended; 1, beginning of flexion of hips and knees, arms extended; 2, stronger flexion of legs, arms extended; 3, arms slightly flexed, legs flexed and abducted; 4, full flexion of arms and legs. Square window: The hand is flexed on the forearm between the thumb and index finger of the examiner. Enough pressure is applied to get as full a flexion as possible, and the angle between the hypothenar eminence and the ventral aspect of the forearm is measured and graded according to the diagram. (Care is taken not to rotate the infant’s wrist while performing this maneuver.) Arm recoil: With the infant in the supine position, the forearms are first flexed for 5 seconds, then fully extended by pulling on the hands, and then released. The sign is fully positive if the arms return briskly to full flexion (score 2). If the arms return to incomplete flexion or the response is sluggish, it is scored as 1. If they remain extended or show only random movements, the score is 0. Popliteal angle: With the infant supine and the pelvis flat on the examining couch, the thigh is held in the knee-to-chest position, with the examiner’s left index finger and thumb supporting the knee. The leg is then extended by gentle pressure from the examiner’s right index finger behind the ankle, and the popliteal angle is measured. Scarf sign: With the infant supine, the examiner takes the infant’s hand and tries to put it around the neck and as far posteriorly as possible around the opposite shoulder. This maneuver is assisted by lifting the elbow across the body. How far the elbow goes across is measured and graded according to the illustrations. Score 0, elbow reaches opposite axillary line; 1, elbow reaches between midline and opposite axillary line; 2, elbow reaches midline; 3, elbow does not reach midline. Heel-to-ear maneuver: With the infant supine, the examiner draws the infant’s foot as near to the head as it will go without forcing it. The examiner observes the distance between the foot and the head, as well as the degree of extension at the knee, and grades according to the diagram. Note that the knee is left free and may draw down alongside the abdomen. (Reprinted with permission from Ballard J, Novak K, Driver M: A simplified score for assessment of fetal maturation of newly born infants, J Pediatr 95:769, 1979.)

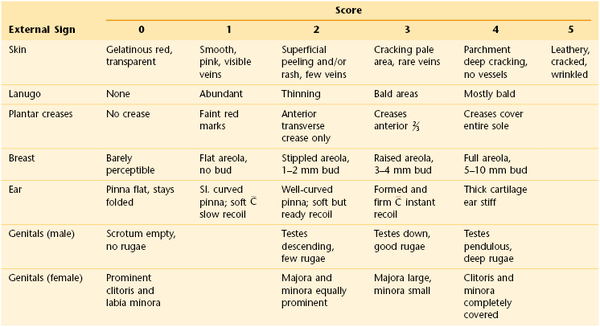

Table 21–2

Scoring System for External Criteria of Ballard Clinical Assessment

, Cartilage; Sl., slightly. Reprinted with permission from Ballard J, Novak K, Driver M: A simplified score for assessment of fetal maturation of newly born infants, J Pediatr 95:769, 1979.

, Cartilage; Sl., slightly. Reprinted with permission from Ballard J, Novak K, Driver M: A simplified score for assessment of fetal maturation of newly born infants, J Pediatr 95:769, 1979.

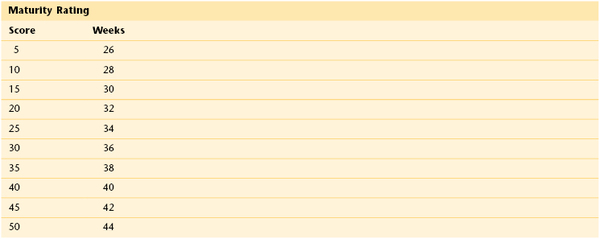

The total scores of the neurologic and external signs are summed. The sum is then correlated with the gestational age, according to the graph shown in Figure 21-4. A sum between 46 and 60 is associated with a gestational age of 37 to 41 weeks. A child with a gestational age from 37 to 41 weeks is denoted a term infant, although some authorities believe that a gestational age of 38 to 42 weeks defines a term infant (see Fig. 21-4). A child with a gestational age of less than 37 weeks is preterm; one with a gestational age of more than 41 weeks (or 42 weeks) is postterm.

Figure 21–4 Graph for determining gestational age on the basis of neurologic criteria and external signs.

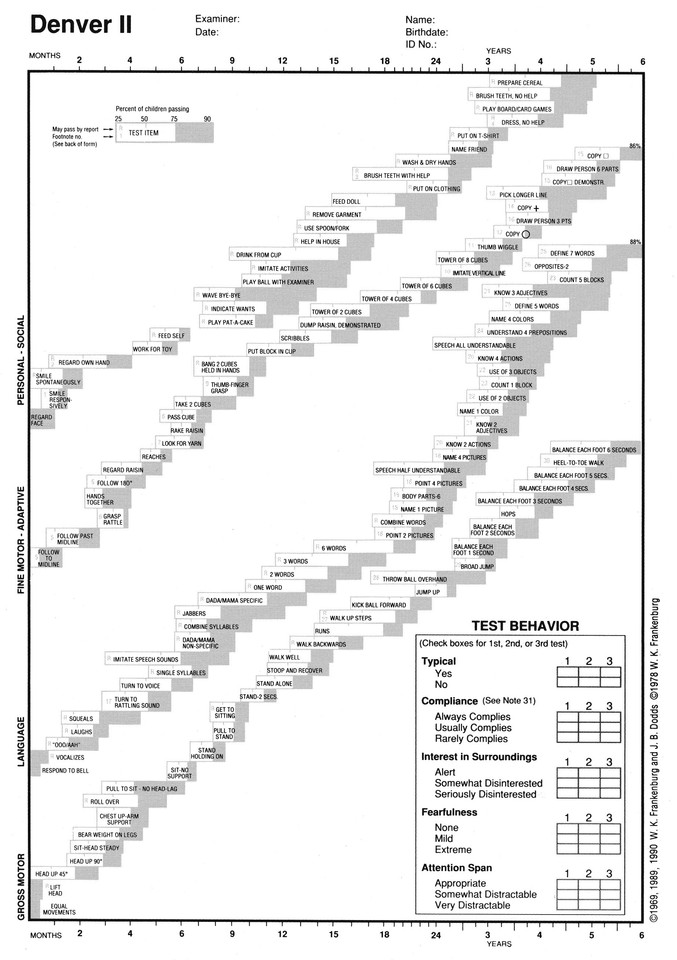

The newborn infant is also weighed, but weight alone does not determine maturational age. The birth weight is correlated with gestational age according to the standard classification of Battaglia and Lubchenco, which is shown in Figure 21-5. By this method, the infant is classified as being SGA, AGA, or LGA. If the birth weight is between the tenth and ninetieth percentiles, the infant is AGA. If the birth weight is lower than the tenth percentile on the intrauterine growth curve, the newborn is classified as SGA. If the birth weight is higher than the ninetieth percentile, the newborn is called LGA.

The remainder of the examination is usually performed in the warmed environment of the nursery, often within 24 hours after birth. Before examining the child, review some key historical facts with the mother and the nurses:

“Is there any drooling?” Drooling in the newborn can be a sign of esophageal atresia.

“Has there been any respiratory distress, noisy breathing, or cyanosis?” Infants are obligatory mouth-breathers. An obstruction of their nasal passages, such as the choanae, can lead to cyanosis and severe respiratory distress in the immediately newborn period. Cyanosis is also an important clue to congenital heart disease.

“Has there been any abdominal distention?”

“Has the child passed meconium?” Failure to pass meconium25 by 48 hours of age may indicate bowel obstruction, meconium ileus (seen in cystic fibrosis), or Hirschsprung’s disease.

Thus this review of systems for a newborn is brief but significant.

The comprehensive examination begins with inspection. If the infant has achieved temperature stability, then he or she should be undressed except for the diaper. Is there evidence of respiratory distress or cyanosis? If so, immediate intervention is indicated. If not, proceed with the rest of the examination. The following description of the examination is in a head-to-toe sequence. However, the examiner must usually vary the order when actually performing the examination, using the infant’s quiet state to listen to the heart and lungs, catching glimpses of the eyes when the infant opens them, and taking advantage of crying spells to examine the mouth.

The respiratory rate and degree of respiratory effort are carefully assessed while the infant is undressed. The respiratory rate of a newborn usually averages from 30 to 50 breaths per minute. Observe the respiratory rate for 1 to 2 minutes because periods of apnea and periodic breathing are common, especially among preterm infants. Look for grunting respirations and for chest retractions, each of which is evidence of respiratory distress.

Determine the pulse by auscultation of the heart. The average heart rate of a newborn ranges from 120 to 140 beats per minute. There are wide fluctuations; the rate increases to as fast as 190 during crying and decreases to as low as 90 during sleep. A heart rate lower than 90 is of concern.

Measure the temperature by using a rectal thermometer. The infant is placed in a prone position on an examining table or in the examiner’s lap. The infant’s buttocks are spread, and a well-lubricated thermometer is inserted slowly through the anal sphincter to approximately 1 inch (2.5 cm). Note that this also establishes that the anus is patent, thereby ruling out the existence of imperforate anus. After 1 minute, the temperature may be read. Newborn infants often have relative thermal instability, and for this reason the ambient temperature should also be determined. Achieving temperature stability is one of the early adaptational challenges for a term infant and takes much longer for preterm infants. Note that the nursing staff usually measures the newborn’s temperature.

Basic measurements are taken next. The infant’s length is measured from the top of the head to the bottom of the feet; the length is usually between 18.5 and 20.5 inches (47 and 52 cm). The head is measured at its greatest circumference around the occipitofrontal area. In general, three measurements are taken, the largest of which is recorded. The head circumference is usually 13.5 to 14.5 inches (34 to 37 cm). These and all other measurements performed during the physical examination should be plotted on appropriate growth curves, correcting for the gestational age.

Note the posture. A normal term newborn keeps the arms and legs symmetrically flexed. Relaxation of the limbs is suggestive of neurologic depression and necessitates further evaluation. The finding of one side flexed while the other side is relaxed is abnormal; such posture is suggestive of an injury, either neurologic or musculoskeletal, that occurred before or during the birthing process.

Note the movements. Normally, all four limbs should be moving in a random and asymmetric manner. Fine movements of the face and fingers are usually present. Abnormal movements include jerky, symmetric, coarse movements. All extremities should be moving, with full range of motion seen at some time. Injury to the brachial plexus may cause paralysis of the upper arm. This injury may result from lateral traction on the head and neck during delivery of the shoulder. Erb’s palsy produces an inability to spontaneously abduct the arm at the shoulder, rotate the arm externally, flex the elbow, and supinate the forearm. This injury to the fifth and sixth cervical nerves results in a characteristic position of arm adduction, with elbow extension, forearm pronation, and arm internal rotation known as the “waiter’s tip” position. The grasp reflex is usually preserved. Klumpke’s paralysis is much rarer, and results from injury to the seventh and eighth cervical nerves, producing paralysis of the hand and forearm. The grasp reflex is absent. Involvement of the first thoracic nerve with Klumpke’s paralysis may also result in ipsilateral ptosis and miosis, or Horner’s syndrome. The prognosis of any brachial plexus palsy depends on whether the nerve or nerves were lacerated or only bruised. If the palsy is related only to edema of the nerve fibers and not to actual injury, function usually returns within a few months.

Skin

Skin color in newborns is related partially to the amount of fat present. Preterm infants generally appear redder because they have less subcutaneous fat than do term infants.

The newborn has vasomotor instability, and the color of the skin may vary greatly from moment to moment and from one area of the body to another. It is often noted that when the infant is lying on one side for a time, a sharp color demarcation appears: The lower half of the body becomes red, and the upper half is pale. Seen more commonly in preterm than in term infants, this has been termed the harlequin color change and is benign. The episodes may persist from 30 seconds to 30 minutes.

Inspect for cyanosis or acrocyanosis. Acrocyanosis is a benign condition in which the hands and feet are cyanotic and cool but the trunk is pink and warm. This condition is common among newborns. In central cyanosis, the tongue and gums are also blue. Persistent central cyanosis can be suggestive of respiratory abnormalities or the presence of cyanotic congenital heart disease.

Is plethora present? Plethora is a condition marked by an excess of blood and a marked redness of the complexion. Plethora in the newborn usually indicates high levels of hemoglobin.

Is pallor present? Pallor may be associated with anemia or, more commonly, with cold stress and peripheral vasoconstriction. Pallor may also reflect asphyxia, shock, sepsis, or edema. It should be recognized that the presence of pallor may mask cyanosis in a newborn with circulatory failure.

Are there any skin findings from birth trauma, manifested by petechiae, ecchymoses, or lacerations?

Physiologic jaundice is found in almost 50% of all term newborns by the third or fourth day after birth. This finding, which is even more prevalent among preterm infants, results from delay in the maturation of enzymatic processes in the liver. In most cases, jaundice is a self-limited condition, resolving after 96 hours of age. However, very high levels of bilirubin in the newborn’s serum can lead to a condition known as kernicterus, in which permanent neurologic damage may occur. As such, it is important to monitor the serum bilirubin level and to treat elevated levels with phototherapy.

Icterus appearing before the third day may indicate a pathologic condition. Disorders that must be considered are hemolytic anemia, caused by blood group incompatibility or by bacterial or viral infections, and galactosemia, an inborn error of galactose metabolism. Visible jaundice in newborns does not appear until the serum bilirubin is approximately 5 mg/dL. When the level exceeds this threshold, the jaundice spreads in an orderly manner, from the top of the head to the soles of the feet. When the soles become yellow, the serum bilirubin level has usually reached 12 mg/dL. Many centers now use a transcutaneous bilirubinometer to facilitate recognizing potentially dangerous levels of jaundice.

Observe the pigmentation. Large, slate-blue, well-demarcated areas of pigmentation in the sacrogluteal area or elsewhere are called dermal melanocytosis, originally referred to as mongolian spots, and are normal variants. Ninety percent of all dermal melanocytosis are in the buttock area. These spots fade and disappear by 5 to 6 years of age in 98% of children who have them. Dermal melanocytosis is present in more than 90% of African-American newborns and 70% of Asian-American newborns but in fewer than 10% of white newborns. Figure 21-6 shows a classic dermal melanocytosis.

Figure 21–6 Dermal melanocytosis.

Vascular nevi may be isolated defects or part of a syndrome and can be classified as malformations or hemangiomas. Hemangiomas are the most common tumors of infancy. They may be flat and are commonly caused by dilated capillaries, or they may be mass lesions and consist of large, blood-filled cavities. The port wine stain, also known as the nevus flammeus, consists of dilated capillaries and appears as a pink to purple macular lesion of variable size. It can be as large as half the body. It manifests at birth and represents a permanent defect. Figure 21-7 shows a port wine stain involving the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. Often, children with port wine stains in this area have associated capillary hemangiomas of the ipsilateral meninges and occipital portion of the cerebral cortex, a condition known as Sturge-Weber syndrome. Intellectual disabilities, seizures, hemiparesis, contralateral hemianopsia, and glaucoma are often seen in the first few years of life. Figure 21-8 shows a child with Sturge-Weber syndrome (see also Fig. 7-27).

Figure 21–7 Port wine stain.

Figure 21–8 Sturge-Weber syndrome.

The strawberry nevus, or capillary hemangioma, is a bright red, protuberant lesion seen commonly on the face, scalp, back, or anogenital area. It may be present at birth, but it more commonly develops within the first 2 months of life. Girls are affected more often than boys. The lesion may expand rapidly, reach a stationary period, and then regress. More than 60% of capillary hemangiomas become involuted by the time the child is 5 years of age, and 95% become involuted by 9 years of age. Figure 21-9 shows a strawberry nevus.

Figure 21–9 Strawberry nevus.

The cavernous hemangioma is more deeply situated and is a cystic, often compressible lesion that is more diffuse and ill-defined than the capillary hemangioma. The overlying skin may appear normal in color or may have a bluish hue. Like the capillary hemangioma, the cavernous hemangioma has a growth phase followed by a period of involution. If it is located near the trachea, life-threatening compression may result when the hemangioma enlarges. The child pictured in Figure 21-10 has a combination of a strawberry nevus and a cavernous hemangioma. The strawberry lesion overlies the cavernous hemangioma. The child pictured in Figure 21-11 has a mixed hemangioma; it has both superficial capillary and deep cavernous components. This lesion involuted by the child’s third year of life. Although these lesions usually resolve by the seventh year of life, they may leave scarring, loose skin, and telangiectases. Also, as part of the Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome, they may be associated with overgrowth of a portion of the body (a complete side, an arm, a leg, or a smaller portion.)

Figure 21–11 Mixed hemangioma.

Other birthmarks that may suggest the presence of an underlying genetic disorder include café-au-lait spots (see Fig. 5-46) and hypopigmented macules. One or two café-au-lait spots, the color of coffee with milk, are not uncommon in the newborn. In dark-skinned individuals, the macule is darker than the surrounding skin and should be described as “café sans lait” (coffee without milk). The presence of more than six of these spots, measuring greater than 0.5 cm, is the hallmark of neurofibromatosis type I, an autosomal dominantly inherited condition that combines café-au-lait spots, axillary or inguinal freckles (see Fig. 5-49), pigmented hamartomas in the iris (Lisch nodules), and bony abnormalities such as scoliosis and pseudarthrosis with benign tumors of the Schwann cells called neurofibromas. In this condition, multiple café-au-lait spots are frequently the presenting feature.

The presence of hypopigmented macules suggests a condition known as tuberous sclerosis complex. In this disorder, the hypomelanotic macules (Fig. 21-12) are often described as ash-leaf shaped, with one side smooth and the other side jagged, and are associated with other dermatologic manifestations (facial angiofibromas known as adenoma sebaceum, and shagreen patches, as seen in Fig. 21-13), the presence of benign tumors in the brain (cortical “tubers,” subependymal nodules), kidney (angiomyolipomas and cysts), and heart (rhabdomyomas), seizures, and mental retardation. Because of the significance of some of these findings, the presence of multiple hypomelanotic ash-leaf spots noted during an initial evaluation should trigger a full evaluation for associated features.

Figure 21–13 Shagreen patch.

Is a rash present? Bullous lesions may be present at birth. One or two blisters on the lips or hands may represent “sucking blisters.” Widespread blisters, many of them ruptured and leaving a collarette of scale with underlying pigmentation, represent transient neonatal pustular melanosis, which is benign. This condition, present at birth, is of unknown origin and is most commonly found on the trunk and extremities. It is seen in 5% of African-American newborns and in 0.5% of white newborns. Figure 21-14 shows transient neonatal pustular melanosis in a newborn. Notice the intact pustule and the ruptured pustule with a collarette of scale. The vesicopustules last 48 to 72 hours, and the pigmented macules may last 3 weeks to 3 months.

Figure 21–14 Transient neonatal pustular melanosis.

Erythema toxicum is a common rash among newborns. It is a self-limited, benign eruption of unknown cause, consisting of erythematous macules, papules, and pustules. The condition is seen in 40% of otherwise healthy term newborns; it is not seen in premature newborns. The lesions may appear anywhere on the body except on the palms and soles and have the appearance of flea bites. It is most commonly seen during the first 3 to 4 days after birth but may be present at birth. The lesions may rarely last 2 to 3 weeks. Erythema toxicum is pictured in Figure 21-15.

Figure 21–15 Erythema toxicum.

Milia on the face are seen in almost 50% of all newborns. Milia appear as tiny whitish papules on the cheeks, nose, chin, and forehead and usually disappear by 3 weeks of age.

Prenatal or transplacental infections of the fetus may manifest with cutaneous symptoms. If a pregnant woman contracts rubella in the first trimester, there is a 20% chance that the infant may have the congenital rubella syndrome. A cutaneous sign of congenital rubella is the blueberry muffin lesion. Such lesions, which represent sites of extramedullary hematopoiesis, are bluish-red macular or papular lesions ranging in size from 2 to 8 mm. They are noted at birth or within the first 24 hours and appear on the face, neck, trunk, or extremities. Other features of the congenital rubella syndrome include eye defects (especially cataracts), cardiac defects (e.g., ventricular septal defects and valvular defects), deafness, bone lesions, hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, thrombocytopenia, interstitial pneumonitis, and, later, mental retardation. Figure 21-16 shows a child with the classic blueberry muffin rash of congenital rubella.

Figure 21–16 Congenital rubella with a blueberry muffin rash.

Congenital syphilis may present as an erythematous maculopapular rash that later turns brown or becomes a hemorrhagic vesicular rash. This is a rash that commonly affects the palms and soles.

Is hair present? A newborn’s skin may be covered with fine, soft, immature hair, known as lanugo hair. Lanugo hair frequently covers the scalp and brow in premature infants but is usually absent in term infants, except perhaps on the ears and shoulders. Inspect the lumbosacral area for tufts of hair. Tufts of hair (hypertrichosis) in this area are suggestive of the presence of an occult spina bifida or a sinus tract, anomalies that may be an external sign of tethering of the spinal cord. Figure 21-17 shows sacral hypertrichosis in a child who had a tethered spinal cord. Examine the fingernails. In a postterm infant, the fingernails are long and may be stained yellow if meconium was present in the amniotic fluid. Hypoplastic fingernails may be a marker for fetal alcohol syndrome.

Figure 21–17 Sacral hypertrichosis.

Examine the dermatoglyphics of the fingers, palms, and soles. In addition to their value for identification purposes, these patterns are important indicators of genetic abnormalities. Normal finger dermatoglyphic patterns are the loop, whorl, and arch. The loop is normally the most prevalent pattern. The arch is the least prevalent pattern, and the presence of more than four arches is usually abnormal, often signaling the presence of congenital abnormalities. A single transverse palmar crease, known as a simian crease, is found in more than 50% of individuals with chromosomal abnormalities such as trisomy 21; however, simian creases are present in 10% of individuals who are normal.

Head

Examination of the head involves a thorough assessment of its shape, symmetry, and fontanelles. The skull may be molded, especially if the labor was prolonged and the head was engaged for a long period. The skull of a child born by primary cesarean section without preceding labor has a characteristic roundness.

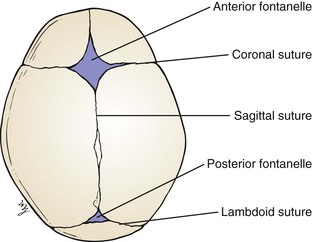

In the newborn, the sutures are frequently felt as ridges as a result of the overriding of the cranial bones by molding as the skull passes through the vaginal canal. Palpate the fontanelles, or “soft spots.” The anterior fontanelle is located at the junction of the sagittal and coronal sutures, is usually 1.5 to 2.5 inches (4 to 6 cm) in diameter, and appears diamond-shaped. The triangular posterior fontanelle is located at the junction of the sagittal and lambdoid sutures and measures 0.4 to 0.8 inch (1 to 2 cm) in diameter. Normally, the fontanelles are flat. A bulging fontanelle may be indicative of increased intracranial pressure; a depressed fontanelle may be seen in dehydration. Normally during crying, the fontanelles bulge. Pulsations of the fontanelles reflect the pulse. The anterior fontanelle normally closes by 18 months of age, but there is a wide range of normality; the posterior fontanelle should be closed by 2 months of age and may already be closed in the neonatal period. The locations of the fontanelles are shown in Figure 21-18.

Figure 21–18 Location of the fontanelles.

Caput succedaneum is edema of the soft tissues over the vertex of the skull that is related to the birth process during a vertex delivery. The normal movement of the fetal head through the birth canal produces a marked molding of the very soft fetal skull and scalp edema. This swelling, which is present at delivery, crosses the sutures and resolves in the first few days. In a face presentation, there can be diffuse swelling, discoloration, and swelling of the newborn’s face.

Caput succedaneum should be differentiated from a cephalohematoma, which is a subperiosteal hemorrhage limited to one cranial bone, often the parietal. There is no discoloration of the overlying scalp, and the swelling does not cross the suture line. The swelling is usually not visible until several hours or days after birth, inasmuch as subperiosteal bleeding is generally a slow process. Approximately 15% of cephalohematomas are bilateral, and each is palpably distinct from the other side. No treatment is required for cephalohematomas, which are generally resorbed by 2 to 12 weeks, depending on the size. Figure 21-19 shows a newborn with a caput succedaneum; Figure 21-20 shows a child with a cephalohematoma. Note in Figure 21-20 that the swelling stops in the midline at the sagittal suture; this is characteristic of a cephalohematoma, and the extravasated blood may contribute to jaundice.

Figure 21–19 Caput succedaneum.

Figure 21–20 Cephalohematoma.

A few days after delivery, the head shape should return to normal. An unusual head shape may be due to craniosynostosis, premature closure of the sutures of the skull, or may represent a deformational process, caused by unusual forces acting on the otherwise normal skull. The latter condition, termed plagiocephaly, may become worse during the first few months of life because the infant will prefer to rest his or her head on one side. This position of comfort dictates which side of the occiput is more prominent. After 6 months, when the infant is able to sit unassisted, the plagiocephaly caused by intrauterine deformation gradually resolves.

Craniosynostosis is a malformation caused by sutural closure at an unusually early age. Closure of the coronal sutures leads to brachycephaly, in which the head is short in the anteroposterior diameter and wider laterally. This is the opposite of the head shape that results from premature closure of the sagittal suture, a head that is long in the anteroposterior diameter and narrow laterally (a skull shape known as dolichocephalic or scaphocephalic). Premature closure of one lambdoid suture leads to posterior plagiocephaly that does not resolve on its own.

Inspect the skull for symmetry.

Inspect the scalp for lesions from fetal scalp electrodes, used for monitoring fetal well-being during difficult labors, and for areas of alopecia. A 0.4- to 0.8-inch (1- to 2-cm) well-demarcated area of smooth shiny skin with no hair may represent aplasia cutis congenita, an abnormality of fetal development of unknown cause. Usually an isolated finding in an otherwise well newborn, aplasia cutis also occurs commonly in trisomy 13, and may result from fetal exposure to the antithyroid medication, methimazole.

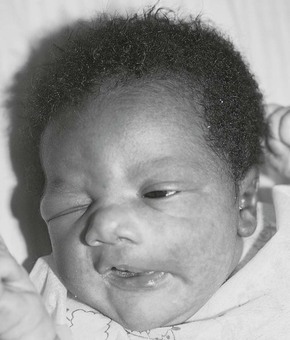

Inspect the face for symmetry. The eye creases should be equal. Observe the infant as he or she sucks or cries. The mouth should remain on a level plane. If it is asymmetric, suspect a facial paralysis or a congenital anomaly of one or more facial muscles, a condition known as asymmetric crying facies syndrome (a condition that may be associated with other congenital malformations, such as congenital heart disease). Figure 21-21 shows a 2-day-old neonate born by forceps extraction with a traumatic peripheral facial nerve palsy.25 Notice the involvement of the entire left side of the face with failure of the left eye to close and the drooping of the corner of the left side of the mouth. Failure of eye closure on the affected side is usually the first noticeable sign of a peripheral facial palsy. During labor and delivery, the peripheral portion of the facial nerve may be compressed over the stylomastoid foramen through which the nerve emerges, or where the nerve traverses the ramus of the mandible.

Figure 21–21 Traumatic facial palsy, left.

The face may reveal abnormal features such as epicanthal folds, widely spaced eyes, or low-set ears, each of which may be associated with congenital defects.

Eyes

Several attempts to evaluate the eyes of the newborn may be necessary. Eyelid edema related to the birth process, infections, or medications used to prevent infections may make this part of the examination difficult.

Inspect the eyes for symmetry. The eyes should be the same size and should be at the same depth in the orbits. Bulging eyes may be a sign of congenital glaucoma. Microcornea or microphthalmia may result from congenital rubella or other teratogens.

Assess whether the eyes are normal distance from one another. If there is a concern about the eyes being too close together (hypotelorism) or too far apart (hypertelorism), careful measurements should be taken. These include inner canthal distance (distance between the inner canthi), outer canthal distance (distance between the outer canthi), and interpupil distance (distance between the pupils). Each of these measurements should be plotted on an appropriate growth curve.26 Hypotelorism (all measurements less than the fifth percentile) may be associated with midline defects of the brain, such as alobar holoprosencephaly; hypertelorism can be part of a number of multiple malformation syndromes, such as cleidocranial dysplasia and Crouzon syndrome.

The best method of evaluating the eyes of a newborn is to hold the infant upright at arm’s length while slowly rotating him or her in one direction. The infant’s eyes usually open spontaneously.

Inspect the sclerae. In newborns, the sclerae may be icteric as a result of physiologic jaundice (described earlier). When icterus is absent, the sclerae of a young infant may appear bluish. During the first 6 months, the connective tissue of the sclera becomes thicker, leading to the normal white color expected in an adult. Persistence of blue color of the sclera after 6 months of age is suggestive of the presence of a connective tissue disorder, such as osteogenesis imperfecta or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (see Fig. 7-52).

Inspect the cornea. The cornea should be clear. Cloudiness or a corneal diameter that is greater than 0.4 inch (1 cm) may be indicative of congenital glaucoma. Enlargement of the orbit, a condition known as buphthalmos, may also be seen in individuals with congenital glaucoma.

Inspect the iris. The iris of a newborn may be pale because full pigmentation does not occur before 10 to 12 months of life. Is an abnormal ventral cleft present in the iris? This cleft, known as a coloboma, is associated with defects in the iris and/or retina (see Figs. 7-66 and 7-146). A coloboma may occur in isolation, but is commonly associated with chromosomal abnormalities such as trisomy 13 or 18 and the syndrome of coloboma, heart disease, atresia choanae, retardation of growth or development, genitourinary tract anomalies, and ear anomalies (CHARGE). In rare cases, the irides are absent; this condition, known as aniridia, is associated with the susceptibility to development of Wilms tumor. Is there a ring of whitish dots at the periphery of the iris? These dots are best seen in a slit-lamp examination by an ophthalmologist, but the ring is sometimes visible to the naked eye. These dots, called Brushfield spots, may be associated with trisomy 21 or may be normal.

Inspect the conjunctivae. Small subconjunctival hemorrhages are common, a result of the forces involved in the birth process. They heal without any effect on the child’s vision. As a result of the erythromycin drops28 instilled at birth, there may be some inflammation of the conjunctivae, as well as edema of the eyelids.

The pupils of neonates are usually constricted until approximately the third week after birth. Pupillary reflexes are present but hard to interpret in this age group.

Rotate the infant slowly to one side. The eyes should turn in the direction to which he or she is being turned. At the end of the motion, the eyes should quickly look back in the opposite direction after a few quick, nonsustained nystagmoid movements. This is termed the rotational response, and its presence establishes that the motor control of the eyes is intact.

Place the infant back on his or her back.

To test for visual acuity in the newborn, the examiner must rely on indirect methods such as the response to a bright light, known as the optical blink reflex. This reflex is normally observed when a bright light is shined on each eye: the newborn blinks and dorsiflexes the head. The visual acuity of newborns has been estimated to be approximately 20/100 to 20/150, according to their ability to fixate on and imitate the adult face.

In all newborns, the presence of the red reflex bilaterally suggests grossly normal eyes and the absence of glaucoma, cataract, or intraocular disorders. Determine the presence of the red reflex by holding the ophthalmoscope 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30.5 cm) away from the infant’s eyes. The presence of the red reflex indicates that there is no serious obstruction to light between the cornea and the retina. If a red reflex is absent, funduscopic examination is required at this time. A funduscopic examination by an ophthalmologist is also indicated if you suspect any of the intrauterine infections associated with chorioretinitis, such as toxoplasmosis, congenital rubella, or cytomegalovirus infection.

Ears

Inspect the external ear. An imaginary line from the inner and outer canthus of the eye toward the vertex should be at or below the level of the superior attachment of the ear. Low-set ears are often associated with congenital kidney defects or chromosomal disorders. Frequently, the ears are misshapen as a result of intrauterine positioning. Such misshaping usually resolves within 1 to 2 days after birth. In rare instances, one ear is malformed and reduced in size. This condition, microtia, is often associated with a condition called hemifacial microsomia or Goldenhar syndrome. It is frequently associated with other anomalies on the ipsilateral side of the face.

Are any skin tags present? A skin tag or cleft in front of the tragus often represents a remnant of the first branchial cleft and may be an isolated anomaly or part of a more widespread group of malformations, such as Treacher Collins syndrome or the aforementioned hemifacial microsomia.

Hearing in newborns may be tested by using the primitive acoustic blink reflex. Blinking in response to snapping of the fingers or a loud noise indicates that the newborn can hear. This is a crude test with low sensitivity. A negative response should be further tested with a specific pure-tone screening device. Most states now mandate neonatal hearing screening before discharge from the birth hospital. The parents of a child who passes the screen can be told with confidence that their child has normal hearing at birth. (Some congenital causes of deafness may cause progressive hearing loss over the first 2 years of life.) Only a fraction of children who fail the screen do in fact have hearing deficits.

The external canal should be inspected. Hold the otoscope (as indicated in Chapter 8, The Ear and Nose) by bracing it against the newborn’s head. Insert the otoscope by pulling the pinna gently downward. The external canal is usually filled with vernix caseosa, and so the tympanic membrane may not be seen. If the tympanic membrane can be seen, usually only the most superior portion is visualized. The tympanic membrane may appear to be bulging, with amniotic fluid behind it. This is a normal condition. Rotation of the tympanic membrane to the adult position occurs within 6 to 12 weeks.

Nose

If this has not already been done in the delivery room, patency of the nasopharynx is determined by passing a soft, sterile, 6-French catheter through each external naris and advancing it into the posterior nasopharynx. This test rules out the presence of unilateral or bilateral choanal atresia, which is a cause of severe respiratory distress in newborns. Newborns are nasal breathers, and obstruction to nasal flow can cause considerable distress; the infant with nasal obstruction is cyanotic and distressed at rest, but the cyanosis diminishes when he or she cries. Choanal atresia may occur as an isolated anomaly (in which case, more than 90% of affected individuals are female), or it may be part of the CHARGE syndrome, which was mentioned in the discussion of iris colobomas.

Mouth and Pharynx

Assess the lips and philtrum. Is there a cleft of the lip? This may be to the left or the right of the midline and may be unilateral or bilateral. Is the philtrum well formed, with normal architecture? Flattening of the philtrum is seen in infants with fetal alcohol syndrome.

Test the sucking reflex. Put on a glove, and insert your index finger into the newborn’s mouth. A strong sucking reflex should be present. The sucking reflex is usually strong by 34 weeks’ gestation and disappears at 9 to 12 months of age. Feel for any clefts in the palate.

Inspect the gingivae. The gums should be raised, smooth, and pink.

Inspect the tongue. The normal frenulum may be short or may extend almost to the tip of the tongue. Because the production of saliva is limited in the first few months of life, the presence of excessive saliva in the mouth is suggestive of esophageal atresia.