The Patient in the Community

The role of the physical therapist in the community varies widely. Over the years, this role has changed in response to a range of factors, including epidemiological indicators of chronic conditions, advances in medical and surgical management, and policy changes. Lifestyle-related conditions and their associated comorbidity are health care priorities necessitating substantial community support, often for many years (Chapter 1). In addition, other chronic systemic conditions have well-documented cardiovascular and pulmonary consequences (Chapters 6 and 13). Policy changes during the 1980s resulted in the emergence of diagnostic-related groupings (DRGs), which led to patients being discharged from the hospital at more acute stages of illness. Further, the Balanced Budget Act of 19971 narrowed the criteria for those who qualified for prolonged inpatient postacute care, resulting in patients being transitioned home from extended care facilities sooner than they had been previously. The combination of these factors has changed the role of physical therapy in the community.

Physical therapy is provided in all inpatient care settings, including subacute hospitals, Medicare or another form of insured care skilled nursing settings, long-term acute care facilities, and rehabilitation facilities with transitional care units to facilitate functional progression so that patients are able to return home within days or weeks. Thus rehabilitation, by increasing the number of patients who return home, rather than remaining or being placed in facilities, is a way of reducing cost while maintaining care standards.2 Changes in health care reimbursement from third-party payers affect patients’ access to physical therapy services. Although such policy may be viewed as reducing physical therapy access, new paradigms of health care delivery and models of care for people with chronic conditions may emerge. Epidemiological indicators support patient-centered health care delivery systems and self-care and self-management approaches. The incorporation of self-management principles of practice can improve patients’ quality of life and decrease hospitalization.3–14 This chapter describes how physical therapists can facilitate the management of chronic conditions, particularly lifestyle-related conditions, when practicing in the community and home settings.

Because of dramatic increases in both patient longevity and prevalence of chronic illness, physical therapists see an ever-widening range of diagnoses in their patients in the community. Global aging is occurring at an unprecedented pace. Worldwide, the number of people age 65 and older is expected to increase from 500 million to 1 billion by 2030.15 Physical therapist interventions unique to aging populations need to be considered in relation to the available resources, as well as the challenges that present in the community practice setting more often now that patients are living longer (Chapter 38). Chronic conditions that were previously associated with later stages in life are now presenting earlier in life as a result of changing lifestyle behaviors (Chapter 1). Also, the medical community has improved its ability to quickly and effectively manage complicated acute medical situations—premature births, heart failure, cancer. More patients are surviving diseases once considered fatal and consequently requiring more services to safely and effectively manage the morbidity issues that result. Medical interventions in intensive care units have improved greatly, thus decreasing mortality, but morbidity related to myopathy of critical illness, cognitive impairments, and mental health sequelae has been found to have a significant impact on patients’ ability to resume their prior level of independence (Chapters 33–36).16–21 These patients return home more often and more quickly than in the past, but they often do so accompanied by unresolved cardiovascular and pulmonary impairments. For patients who are too medically fragile to return home or to obtain sufficient medical care at skilled nursing facilities, specialty hospitals have become necessary. These hospitals make it possible for ventilator-dependent or ventilator-assisted patients to receive physical therapy longer and at less cost than an acute care hospital.22

Practicing physical therapy in the community is distinct from practicing in acute care. When people with chronic conditions are living in the community, their focus is on health promotion and optimal health, rather than recovery from an acute episode of a condition or surgical procedure or trauma with frequent changes in their functional status, as is seen in acute care. In the community setting, the patient’s goals are less focused on safety and more on optimal health. Patients’ participation is vital in order to understand their definition of optimal health. Consistent with values of autonomy and independence, shared decision making should always be used— including the patient and family/caregiver in decisions regarding the patient’s care with guidance from the health care team.14,23 This model is at times challenging for health care team members who may feel more comfortable continuing to use a method in which they prescribe a task and tell the patient what to do, with little collaboration. However, the expected level of practice of every physical therapist is evidence-based practice (EBP) in decision making and treatment. The three aspects of EBP are weighted comparably: external clinical evidence, patient circumstances, and individual clinical expertise.24 In this approach to practice, the patient’s goals and his or her ability to carry out an effective plan are important. A patient cannot carry out an effective plan unless he or she is taught how to identify problems and manage or avoid them in daily situations when health care professionals are not present. Patients need a targeted and tailored education to understand how to make the best decisions about their health and to appreciate their responsibility in their own health management.

Chronic Conditions and Self-Management

Many people at home or in long-term care have chronic conditions, often related to lifestyle behaviors. Regardless of whether these conditions are the diagnoses for which they are receiving physical therapy, the related activity limitations and participation restrictions can limit their abilities to participate and progress in their therapy. Chronic conditions can affect the person’s physical capabilities, as well as his or her emotions, attitude, and motivation. Many patients with chronic conditions or functional decline lead full and rewarding lives, but doing so requires the active participation of the patient and the physical therapist to maintain the fullest level of function despite the changes. The choices patients make about their health care, exercises, and methods of self-management will largely determine their health-related quality of life (Chapter 1).

Though people with chronic conditions have multiple impairments requiring adaptation of their lifestyles and schedules, the majority still accomplish what they want and need to do each day. The goal is to augment their knowledge about their symptoms and enable them to work within a collaborative, self-advocacy, and self-help model with their health care team to achieve optimal health. Positive self-management involves a combination of positive emotional outlook, active involvement in decision making, and maintenance of a lifestyle that is as optimal as possible. The interprofessional team needs to engage the patient in his or her care decisions. The physical therapist needs to be caring and fully present with the patient. Although the physical therapist can provide the initial stimulus for the process, effective self-management comes only from within the patient. The physical therapist can continue to be a resource and provide interventions as needed, but the goal is for the patient to be his or her own case manager and decision maker, whenever possible, regarding health care and optimal function (Chapter 1).14,23

Actively playing a role in decision making (i.e., self-management) empowers patients, making them more motivated, positive, active, and successful than passive patients who do only what the physical therapist and other health professionals advise.23,25 A decrease in the number of visits allowed by third-party payers has forced a necessary change towards patient self-management and empowerment, which has led to improved efficiency and effectiveness in treatment. The promotion of positive self-management strategies for a more active, healthy lifestyle is one of the most important competencies of contemporary physical therapists.

The physical therapist facilitates this process by being caring, supportive, and respectful of patient goals and priorities. This has been referred to as a “healing presence,” which may lead to a beneficial, therapeutic, positive experience for the patient.26,27 The American Physical Therapy Association promoted this practice philosophy with the phrase “the science of healing, the art of caring.”

Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Concerns in the Community

One example is a patient with coronary artery disease, who is fully independent in his or her day-to-day activities but not at a maximal functional level because of limited education on how to further improve function. Another example is a patient who cannot resume his or her prior level of independent function after an acute bout of illness or hospitalization because of limits resulting from primary and/or secondary cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunction. Both of these examples illustrate the resultant decrease in such patients’ tolerance for, and ability to independently perform, activities of daily living. Because of these decreases, patients must acquire continued support to maintain their safety and improve their level of function. Those with the least ability to care for themselves after an acute bout of illness transfer into nursing homes or alternative long-term care, and those with higher levels of function move into assisted living facilities or return home with assistance and therapy. Such patients may present with decreased strength, endurance, and balance, leading to decreased independence, mobility, and activity level. Returning home with a decrease in independent functioning may be associated with negative emotions, which may further decrease appetite, activity level, motivation, and social/community interactions (Chapter 1).

Functioning depends on the ability of the patient to maintain all of the components of oxygen transport to support activity. One example is a patient who fell in the parking lot of a hospital where she had been attending a pulmonary rehabilitation program. She was fitted with a long leg cast and discharged home. She reported being short of breath with sit-to-stand transfers, and soon she was hardly able to ambulate across the room with the standard walker she used before. When the physical therapist observed this patient using her bronchodilator metered-dose inhaler, she was using it improperly. After she was instructed on how to use the bronchodilator therapy effectively before activity, the patient’s transfers and her walking ability improved markedly. She was able to coordinate her breathing with her activity, and her endurance further improved. Case reports and professional experiences such as this provide important information for the physical therapist to use in conjunction with the findings of research studies when planning and prescribing interventions for patients at home using evidence-based practice.24

Long-Term Care Facilities and Nursing Homes

The patient’s ability to participate in therapy may be driven by multiple system impairments. Nutritional concerns are a priority. It is important to monitor whether the patient is losing or gaining weight. Poor denture fit and the impact of medications on taste and appetite can affect the patient’s ability to eat. The patient may be depressed, also limiting appetite. The patient may not want to drink because of difficulty getting to the bathroom independently. Determine whether the patient is taking a diuretic and whether he or she has urinary incontinence. Patients who have difficulty managing urination because of frequency or urgency may be less likely to drink sufficient fluids, increasing the risk for hypovolemia, hypotension, decreased cerebral perfusion, and falls.28

Functional gains may be achieved sooner when physical therapy is incorporated into the patient’s daily living with the help of the nurses and aides. This can improve physical capabilities by aiding the learning process, as well as increasing the number of repetitions performed for motor planning. For example, if the patient is taught to use ventilatory strategies with movement, such as inspiring when extending the trunk (Chapter 23), this should be communicated to other caregivers and encouraged during movements that extend the trunk, such as dressing. If the goal is for the patient to walk to meals, the physical therapist and caretakers can have the patient transition from walking as far as he or she can toward the dining room for one meal each day, then walking to two meals each day, and finally, to all meals. The next progression would be to set more functional goals, such as walking to daily activities, to social settings, to the car, and so on; thus walking is no longer associated only with therapy. In-services for nurses and care staff that help reinforce physical therapy interventions can be conducted individually and in formal classes. Instruction can be incorporated into the staff competencies upon hire and annually. One-on-one therapist/aide education sessions should not be replaced by the competencies; rather, they should occur as needed when unique patient needs arise. Educational opportunities such as this can help to make patient education more consistent.

Monitoring Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Status in the Long-Term Care Facility

Because of short hospital stays, patients in long-term care facilities may be less medically stable than patients in the past. With this increase in patient acuity, it is particularly important to monitor each patient’s response to activity. Many long-term care and subacute facilities now provide pulse oximeters and portable electrocardiogram monitors because of increased patient acuity. In addition, physical therapists need to be competent in monitoring blood pressure and heart rates. Auscultation is highly recommended as a clinical competency (Chapter 15). When patients present with acute changes in their status, it is important to utilize any methods of telemedicine available to communicate their medical status to their primary care practitioner. Telemedicine can range from a formal program for AICD-pacer monitoring, for example, to using a secure Internet connection to send video or audio portions of a physical examination.29,30

Vital signs and oximetry need to be evaluated before each physical therapy session and after intervention to assess the physiological response to exercise. Blood pressure and pulse should increase proportionally in relation to the activity (Chapter 18). An increase of 20% to 30% or 20 to 30 beats above resting heart rate would be within normal limits, with a recovery time of 5 to 10 minutes. These responses can be affected by medication; therefore it is vital to know what medications the patient is taking and to understand their impact on the vital sign response.

Physical Therapy in Home

A patient’s successful recovery from acute or long-term loss of independent function is often dependent on the availability of able caregivers. Patients who have a caregiver to help them can discharge home, rather than to a facility. Caregivers are often family, friends, or paid workers who provide this service. Caregivers should be educated to measure vital signs and monitor for changes in physical status, appetite, and behavior as part of their responsibility as the caregiver. Children with chronic illness whose parents can provide care, with or without nursing staff, often return home successfully. These children tend to integrate smoothly into the community, attend school, participate in recreation, function well, and report a high quality of life. Adult sons and daughters are often the caregivers of their parents. In such cases, these adult children may have children of their own, whose needs they are responsible for. This “sandwich generation” is often torn between caring for their aging parents and for their own children.4 It is important for physical therapists to be sensitive to the needs of the patient and the limitations of the caregiver when determining the patient’s safety at home. Many older adult patients remain independent at home, some of them amazing even the most seasoned clinicians with their inventiveness and the extent of their support systems. The physical therapist serves an integral role in teaching patients and families how to manage the impact of disease and elevate each patient’s quality of life to the fullest extent.

Education is especially important in home care. It can be directed to the patient, family, and caregivers and is especially important in ensuring the patient’s safe and independent functioning when the physical therapist is not present. Safety and medical issues can arise unexpectedly. Patients and caregivers must be familiar with the signs and symptoms that indicate a change in their condition (e.g., weakness, discomfort/pain, shortness of breath, changes in secretions, increased fatigue, inability to perform ADLs, depression, and loss of appetite). The physical therapist should gauge the patient’s and/or caregiver’s ability to interpret the medication schedule, understand the prescribed parameters for oxygen use, and recognize when to rest versus when to exercise. The therapist also needs to determine the patient’s ability to self-monitor his or her sign and symptom response to activity (Chapters 17 and 18) both during therapy and during independent activities. Patients and their caregivers need to be able to monitor their cardiovascular and pulmonary status to prevent overexertion and accidents. Because of potential limits in learning, it is important to check the reliability and validity of each patient’s self-assessments. Caregivers and family members can be taught how to monitor the patient’s blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate; they can also be taught to observe for changes in shortness of breath, amount and color of secretions, presence of dizziness or lightheadedness, color changes such as cyanosis or flushed skin, diaphoresis, changes in balance during ambulation, and changes in mental status—and to report such changes promptly to the physical therapist or physician. Patients and caregivers need to know how to manage signs and symptoms, as well as when to call 911 rather than simply calling the physician’s office. If there are concerns about the patient’s judgment and reasoning, which may cause gaps in the patient’s learning, the physical therapist should adapt the education format accordingly.14,31,32

Monitoring Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Status at Home

By using equipment such as portable pulse oximeters (Figure 41-1) and blood pressure cuffs, along with physical examination (Chapters 6, 15, and 32), the physical therapist can do much to determine a patient’s ability to safely perform exercise in the home setting, although there are limitations to the depth of such monitoring and examination. In rural and underserved areas, limited resources may restrict the use of 911 service to life-saving situations only. However, with advances in communication technology, patients and home therapists can gain access to care better than ever before. Advances in chronic disease management in relation to acute changes in status, maintenance care to avoid acute conditions, and research into chronic disease impact and management have come as greater bandwidth has improved the quality of visual and auditory communication.29 According to the National Research Council Report in 2000,33 the Internet is often used for health information websites but is only beginning to be explored for its potential value in clinical decision making, patient education, and clinical outcome improvement—all possible because of the sharing of resources by professionals, “immediate” access to specialists, and more timely adaptations in medication doses, among other advances.

Multiple articles have found limitations in health literacy can decrease a patient’s ability to understand14 prescription instructions, exercise programs, and appointment schedules. For example, in independent studies, Harmon and colleagues13 and Sorensen and coworkers32 noted that patients often do not adhere to their antihypertensive medication prescription regimen for a variety of reasons: a poor understanding of the importance of the medication, limited symptoms of hypertension, and a dislike of the side effects, complicated dosing rules, and financial constraints. This underscores the importance for physical therapists to clarify whether and how patients are taking their prescribed medication; only then can therapists determine whether their patients are sufficiently medicated to safely participate in an exercise program. Furthermore, ongoing communication between patients and their prescribing clinician needs to be fostered on a more frequent basis than is available through office visits.

The use of webcams has great potential as a communication tool for monitoring home-based exercise. This emerging resource provides patients with access to specialists that physical distance may preclude while also allowing more frequent patient interviews than would be possible with only face-to-face meetings. Webcam interviews are more revealing than phone conversations because they convey the patient’s nonverbal, as well as verbal, communication. In this way, the webcam interview is similar to an office visit—perhaps even better because the patient’s level of attention, or inattention, to self-care can often be more evident when the patient is in his or her own home.30,34,35 Webcams can be used by physical therapists to access patients for review and upgrade of their home exercise program. In one study, pulmonary rehabilitation programs performed in an outpatient setting were compared with home programs with telemedicine access, and no statistical difference in outcomes was found.36 Because of the convenience of the webcams, few patients in the study disliked them, but concern was raised about the potential for increased isolation. This concern would need to be addressed if webcams are to be used as a primary means of communication instead of face-to-face meetings. However, the use of a webcam in addition to vital sign response as a way of communicating a patient’s response to exercise can help the home physical therapist to advocate for the patient’s need for medical examination or medication adjustment more clearly than a phone call.

For patients with heart failure, the use of AICDs and biventricular pacemakers is more common because of advances in morbidity and mortality (Chapter 32). Emerging technology is available in some areas to allow the cardiologist not only to monitor a patient’s heart rate and rhythm, but also to measure discrete changes in fluid retention that are evident before activity-limiting symptoms.37,38 Changes in a patient’s clinical examination, combined with interview questions regarding diet and bowel and bladder function, can help a clinician monitor changes in fluid retention and lab values. In cases in which a patient often presents with such symptoms, more sensitive monitoring should be used to better control the patient’s disease if possible. No data point stands alone, so even when advanced telemedicine options are available, the AICD-communicated data should be analyzed in relation to the physical examination and the patient’s interpretation of his or her symptoms.39

Special Monitoring Considerations for Patients on Oxygen

Typically, arterial blood gases are drawn at rest with no patient activity (unless specifically noted, as in an exercise test with a blood gas), so it is not a likely resource to use in the home setting. Generally, Medicare guidelines specify that a patient with an SpO2 of 88% or less during activity or recovery be placed on home oxygen. This value is on the steep part of the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve (Chapter 4). Because oxygen consumption increases proportionately with exercise, a patient may desaturate if oxygen transport is compromised to the extent that it is unable to compensate or respond appropriately to increased demand (Chapter 18). For example, if a patient is on oxygen at rest and the SpO2 is 90%, he or she may desaturate because the red blood cells need to give up more oxygen to supply the exercising muscle. The patient will be short of breath, and oxygen saturation recorded with an oximeter will be abnormal. A drop below 90% is of concern.

The pulse oximeter reading is an indirect measure of arterial oxygen saturation. For otherwise healthy people, this value is at least 97% at rest, and it is clinically acceptable to maintain oxygen saturation at 90% or higher. This saturation corresponds with maintaining PaO2 generally above 55 mm Hg; below 55 mm Hg, a dramatic drop in oxygen saturation is associated with a small drop in PaO2 (Chapter 4).

Patients on oxygen at rest need to have their arterial saturation assessed. Oxygen is a drug, and thus needs to be ordered and prescribed appropriately. The prescription should be written with sufficient flexibility so that it can be adjusted to the patient’s needs. A prescription is written to account for a range of liters of oxygen that is estimated to maintain a level of acceptable saturation. For example, the prescription may state to titrate the patient’s oxygen to 4 L/min to maintain SpO2 over 90%. This is true even for people who retain carbon dioxide and whose oxygen is carefully titrated to prevent a suppression of the hypoxic drive to breathe. Strategies are used to limit risk for CO2 retention and increase ventilation, thereby improving signs and symptoms and reducing risk for desaturation (Chapters 29, 30, and 43).

Though patients may have oxygen established by another professional before the therapy evaluation, it is important to review a few parameters with the patient and caregiver during the course of physical therapy. First, ask patients to tell you their actual oxygen use versus what was prescribed. Next, ask whether they were instructed to adjust the level of oxygen with activity and whether they know how to adjust the dose. If they do adjust the oxygen level, what criteria do they use to determine that they need to adjust the dose?31 Gaps in health literacy and awareness of risk factors can make it difficult for patients to manage their home oxygen safely.

Safety Considerations in the Home Setting

Any evaluation of a patient in a home setting involves an assessment of the patient’s home layout and safety concerns. The risk for injury is increased if a patient needs to perform household tasks that trigger signs and symptoms such as overexertion. Several questions can help establish ways of adapting a patient’s activity intensity and the physical environment, while also engaging the patient in decision making (Box 41-1). Home-care agencies often provide the support of a social worker to help patients identify resources available to them. A physician’s referral may be needed, and the service is generally covered under Medicare. Although these guiding questions are not exhaustive, they provide a basis for part of the assessment and evaluation.

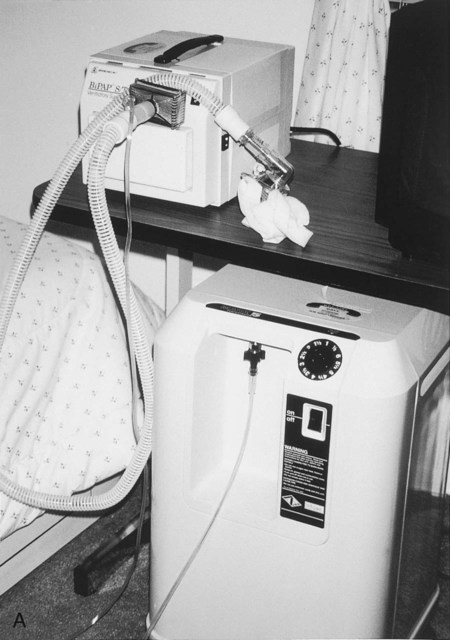

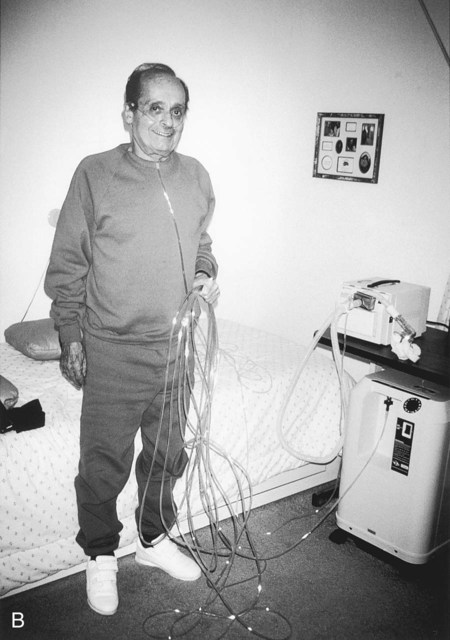

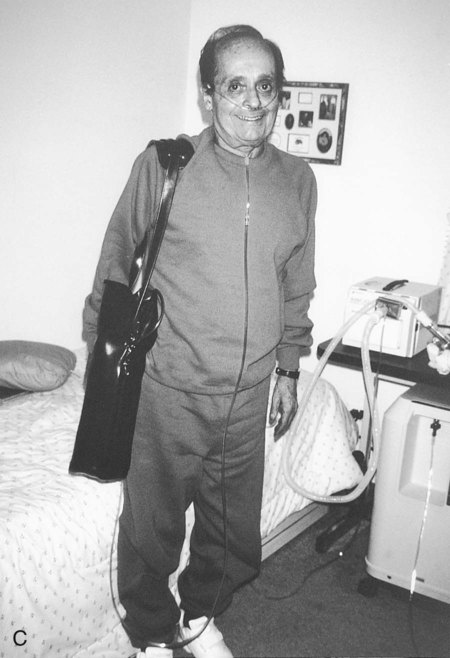

Home Oxygen

Home oxygen devices include oxygen concentrators, tanks, and liquid oxygen systems (Figure 41-2, A, and Chapter 43). Multiple extensions of oxygen tubing may be needed to enable patients to navigate throughout their homes—for instance, going to the bathroom, maneuvering in the kitchen, and walking to the living room (Figure 41-2, B). Although the presence of oxygen in the home is a safety concern that the home-care physical therapist needs to address, long tubing allows for proper oxygen delivery. Compensated flow meters measure the amount of oxygen that reaches the patient, and problems such as kinks are shown by a reduced flow reading. Some portable oxygen systems, particularly demand oxygen systems, may not deliver the amount expected (Figure 41-2, C). Thus a pulse oximeter is needed to ensure that the patient’s arterial saturation is acceptable. Patients are taught to coil the tubing or use a similar strategy to minimize the risk for tripping. To minimize the need for long lengths of tubing, some patients use more than one tank or concentrator.

Patients with sleep apnea may use nocturnal nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) (Figure 41-3) or biphasic continuous positive airway pressure (Bi-PAP), which provides varying levels of ventilator assistance at night. A Bi-PAP machine allows the patient to rest and assists ventilation by providing pressure support on inspiration and exhalation. The patient is encouraged to use the machine at night in particular. Although the patient may have difficulty adjusting to the nasal CPAP, he or she will adapt to the assistance and appreciate its benefits.

Documentation

Functional outcomes consistent with the ICF have become as important as outcomes associated with limitation of function and structure (Chapters 7 and 17). Both short- and long-term goals are linked to functional outcomes that enable patients to be safe and as mobile, functional, and independent as possible in the care setting in which they live. The Guide to Physical Therapist Practice (published by the American Physical Therapy Association) defines practice patterns within the cardiovascular and pulmonary areas to use as a reference to establish goals and treatment plans.40 Goals for patients with cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions, primary or secondary, are typically more detailed than, for example, being able to walk a specific number of feet with a particular device. Goals should also include quantifiable measures of quality—for example, rating of perceived exertion, dyspnea scores, and demonstration of symptom management during functional tasks.

Documentation is the basis for reimbursement. Third-party payers read therapist documentation to determine the examination findings, evaluation, and plan of intervention for the patient. These notes are their primary means of determining a patient’s overall status, including functional outcomes and quality of life. For patients who require long-term physical therapy, thorough and accurate documentation is vital to communication with third-party payers to increase the likelihood that patients will be able to receive the services they need. Teamwork that includes the patient in the decision making and goal planning has become a focus of optimal management in recent years.23 Written and verbal communication is vital to the exchange of information and the targeted and timely progression of care to meet patients’ ongoing and often-changing needs. One rule of thumb must always be remembered: “If it wasn’t written, it wasn’t done.”

Support for People in the Home or Community

Peer groups, in person or over the Internet, can be valuable resources to help patients with chronic conditions make choices concerning their health and life situations.41–46 Many websites and blogs offer free information or may request a nominal fee for membership for patients, health professionals, and supporters to receive newsletters and information in the mail. They host grassroots efforts such as conferences and informational sessions on self-care management and patient empowerment. These support groups publish newsletters that discusses research and provide tips from people living with chronic conditions to help share evidence-based information. These organizations inform people that they are not alone and steer them towards resources that can help with decision making as they strive for optimal health.

Many patient-friendly websites are available for people with COPD and other common chronic conditions, all of which are easily accessed through various search engines or by exploring the links sections of related websites. Box 41-2 lists examples of websites that may be helpful to people with chronic conditions and their families or caregivers.

Therapeutic Goals for Home-Care Patients with Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Dysfunction

Understand the dysfunction or condition and how it results in the changes in signs and symptoms that affect daily functioning.

Understand the dysfunction or condition and how it results in the changes in signs and symptoms that affect daily functioning.

Acquire the necessary adaptive equipment and assistive devices for use in the home and community.

Acquire the necessary adaptive equipment and assistive devices for use in the home and community.

Acknowledge functional limitations (e.g., do not push limits without monitoring responses) to ensure safety.

Acknowledge functional limitations (e.g., do not push limits without monitoring responses) to ensure safety.

Adhere to medication regimens and the direction of physicians and other health professionals. Discuss what is working well—and what is not—and collaborate to find better solutions and interventions.14,32

Adhere to medication regimens and the direction of physicians and other health professionals. Discuss what is working well—and what is not—and collaborate to find better solutions and interventions.14,32

Arrange for caregivers to safely and consistently provide assistance as needed.

Arrange for caregivers to safely and consistently provide assistance as needed.

Learn preventative care strategies (e.g., prevent pulmonary infections and do not increase salt/water intake if on cardiac precautions or taking steroids).

Learn preventative care strategies (e.g., prevent pulmonary infections and do not increase salt/water intake if on cardiac precautions or taking steroids).

Learn ventilatory strategies to increase comfort and function (Chapter 23).

Learn ventilatory strategies to increase comfort and function (Chapter 23).

Learn to self-monitor for signs of impending difficulty (e.g., increased shortness of breath, swelling in ankles, productive cough, changes in mucus, decreased urine output, or rapid weight gain of 2-3 pounds per day).

Learn to self-monitor for signs of impending difficulty (e.g., increased shortness of breath, swelling in ankles, productive cough, changes in mucus, decreased urine output, or rapid weight gain of 2-3 pounds per day).

Pace activities and use energy conservation strategies and rest periods to accomplish more with less physiological demand.

Pace activities and use energy conservation strategies and rest periods to accomplish more with less physiological demand.

Optimize nutrition and hydration and notify health professionals about increases or decreases in weight.

Optimize nutrition and hydration and notify health professionals about increases or decreases in weight.

Seek referral to a dietitian as needed to understand the impact of food choice on health and function if knowledge deficits are affecting health promotion.

Seek referral to a dietitian as needed to understand the impact of food choice on health and function if knowledge deficits are affecting health promotion.

Develop a social support network to provide emotional support when needed.

Develop a social support network to provide emotional support when needed.

Increase general exercise both in terms of a specific exercise program and in completing the necessary tasks of the day to continue functional gains.

Increase general exercise both in terms of a specific exercise program and in completing the necessary tasks of the day to continue functional gains.

Summary

The physical therapist can promote optimal health for patients with chronic and short-term illnesses who live in various community settings. A patient’s path to optimal health involves patient education on effective methods of self-monitoring during activity, adherence to medication regimen, and use of multiple available resources to achieve a higher functional level. Education methods using shared decision making23 can improve patient risk factor reduction, nutrition, and overall functional level more effectively and efficiently than methods in which the patient is not actively part of the solution. People living with chronic conditions can live more safely and independently at home if given sufficient education in a format in which they can understand the goals and expectations before them. As health professionals, physical therapists recommend modifications of patients’ home environments and offer tools to use to best achieve their functional independence and fit their lifestyle based on the best available research. Patients’ participation in such recommendations is vital to improve the degree and longevity of their progress toward optimal health. If patients are to be successful in living independently in the home setting, they need to be independent in their judgments and activities. Physical therapists must respect patients’ choices and decisions, while sharing their own experience, therapeutic judgment, and expertise. The home setting can be a particularly rewarding practice experience, although at times it can be challenging. One thing is certain—if you ask a patient where he or she wants to be, the answer is almost always the same: “There’s no place like home!”

can be attributed to labored breathing, which places considerable metabolic demand on the patient simply to breathe, let alone the challenge of pausing breathing to eat. A nutrition consult can be initiated to assess the patient’s caloric intake and supplement this intake if indicated.

can be attributed to labored breathing, which places considerable metabolic demand on the patient simply to breathe, let alone the challenge of pausing breathing to eat. A nutrition consult can be initiated to assess the patient’s caloric intake and supplement this intake if indicated.