CHAPTER 7 THE ORGANISATION AND DELIVERY OF OPTIMAL DIABETES CARE

BACKGROUND TO THE CHANGING ORGANISATION OF DIABETES SERVICES

INTRODUCTION

In October 1989, government health departments and patients’ organisations from across Europe, under the aegis of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), agreed upon a series of recommendations for diabetes care to be implemented. Called the St Vincent Declaration, this set out goals and targets for improved effective care (WHO/IDF 1990, Krans et al 1992). Subsequent initiatives in the UK have built upon this landmark declaration.

GOVERNMENT POLICIES AND NHS CHANGES

Current government health policy aims to deliver an improved quality of service to individual patients and to the whole population (DoH 1998). General practitioners’ (GPs) contracts with the National Health Service (NHS) now reflect the government’s intention to support and reward improved quality of care in various areas, including diabetes. In order to address the increasing prevalence of the condition, to take account of greater evidence for and availability for effective interventions, and to meet local patient needs, the organisation of diabetes services needs to adopt an integrated approach between primary, secondary and community care.

National Service Frameworks for Diabetes

Authoritative guidelines

Other authoritative guidelines for the management of diabetes are now readily available from:

New General Medical Services (GMS) contract

Since the implementation of the new GMS contract (between an individual general practice and its primary care trust) in 2004, some of general practitioners’ annual income is “performance related”: derived from practices achieving points in the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), which covers a range of clinical, organisational and “patient experience” indicators. The contents and payment stages of the QOF are reviewed and revised on a 2-yearly cycle. For the 2006–2008 cycle, Appendix 3 lists and describes the indicators that are relevant to the delivery of care to diabetics. These are not only the disease-specific indicators, but are also relevant to other clinical and organisational areas.

Performance data from the first year (2004–2005) of QOF showed that, for diabetes, practices across the country achieved, on average with some variations, about 94% of the maximum points available (Khunti 2006, National Diabetes Support Team 2006b).

NHS reorganisation and policy documents

The NHS continues to undergo changes in its organisation. Many of these changes affect how diabetes care is delivered. Government policy has been to reform the delivery of care in the community, particularly with the significant injection of funding into the NHS. A series of policy documents (available on the DoH website) have been published that outline the direction of this reform process. Among these are the new White Paper “Your Health, Your Care, Your Say: a new direction for community services” published in 2006, covering all aspects of the care people need in the community and their own homes (DoH 2006).

The introduction of practice-based commissioning (PBC) may alter radically in some districts the delivery of diabetes care: although quality assurance remains central, implementation of cost management may result in care and resources being shifted from secondary care into the community, possibly into new “frameworks” (National Diabetes Support Team 2006c). Bearing in mind the high proportion of QOF points achieved, practices will probably continue to manage most of their diabetics, but delivery of care for more “complex” individuals or problems may change.

Evaluation of service delivery of diabetes care

The aim of the Healthcare Commission is to promote improvement in the quality of health care and public health in England and Wales. The Commission is committed to annual assessments of the performance of NHS organisations, including components of the diabetes services. A fact sheet summarises this activity (National Diabetes Support Team 2006a).

Patient experience

As part of the QOF, practices are now expected to undertake an annual patient survey, using one of two approved tools (Improving Practice Questionnaire [IPQ], online at www.cfep.co.uk, or General Practice Assessment Questionnaire [GPAQ], online at http://www.gpaq.info/), reflect upon it and produce an action plan.

AIMS

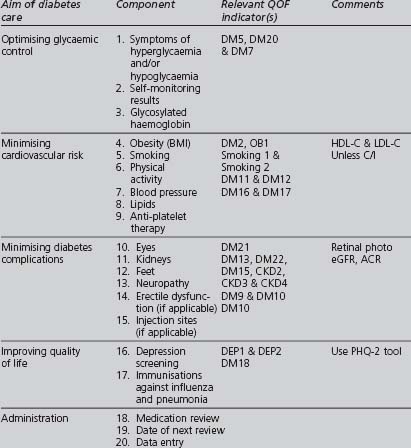

The delivery of high-quality care to type 2 diabetic patients in primary care requires that their needs are identified clearly and correctly, and that the available resources are used optimally to address these needs. Better outcomes are more likely to result if the delivery of care respects and complements the goals chosen by the patient. Patients should be regarded as the main managers of their disease. Diabetics who understand their disease are more likely to have similar aims to those of a caring professional. Table 7.1 summarises a professional’s perspective of suitable aims for the care of individual patients with diabetes.

| Ensure the earliest possible detection of the disease |

| Abolish symptoms of the disease |

| Achieve optimal blood glucose control, avoiding extremes of hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia |

| Prevent or delay, and provide early treatment of diabetes complications |

| Minimise the risk and impact of cardiovascular disease |

| Enable patients to play the fullest possible role in the management of their disease, by providing suitable education and psychological support, maximising self-reliance |

COMPONENTS OF OPTIMAL ORGANISATION WITHIN PRIMARY CARE

Effective delivery of care to diabetics has relied traditionally upon the three Rs of chronic disease management: Registration, Recall and regular Review. “Multifaceted” interventions (such as individualised goal-setting with patients and suitable education) improve the performance of both the practitioners and the organisation, with better outcome measurements of such parameters as blood pressure and glycated haemoglobin (Olivarus et al 2001, Renders et al 2001). A successful “recipe” for diabetes care needs to contain the appropriate “ingredients”:

ACTIVE PARTICIPATION OF DIABETIC PATIENTS IN THEIR CARE

Attention to the following guiding principles should enhance this autonomy:

PRIMARY HEALTHCARE TEAM PERSONNEL

The following points may inform how members of the primary healthcare team can deliver diabetes care more effectively:

Chapter 6 of the Diabetes NSF Delivery Strategy (DoH 2002) outlines issues that relate to workforce planning and development. Although directed more at a district level, the document and its references may be relevant to how individual practices might manage their own personnel.

ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURES AND PROCESSES

The following should enhance the delivery of quality diabetes care in practices:

INFORMATION MANAGEMENT

Optimal information management is an essential ingredient in achieving improved quality in any area of health care. Strategic planning in this area needs to look at what is recorded and how information is handled. Practices may wish to refer to the DoH’s documents Diabetes Information Strategy (DoH Diabetes Information Strategy 2003) and Information for Health (NHS Executive 1998).

Manual records now have only an archive role. The National Programme for Information Technology (NPfIT) is an ambitious national programme to develop an IT system in the NHS. Among its elements that will be relevant to the delivery of care to patients with diabetes are patient records (National Care Records Service), electronic transfer of prescriptions (Electronic Prescription Service) and referrals (Choose & Book). The aims are ambitious, but implementation may prove problematic and the track record of national government-funded IT programmes has been poor.

Content

The data recorded by each practice are determined by clinical, administrative and medico-legal requirements. Any data recorded must have a clear purpose and should not be only “for information’s sake”. QOF indicators and the components of the periodic review could provide the basis for the data that practices wish to record. Precise definitions of all recorded data need to be agreed and understood by all users. All current UK electronic systems use Clinical Terms, known as Read Codes, which are produced and maintained by the NHS Information Authority (NHSIA online). Read Codes for the QOF have been agreed and the relevant documents available from the General Practice Committee of the BMA (West Midlands Local Medical Committee online). Where multiple codes are available for single or similar terms, practices should agree a unique code for each item of data to be recorded and ensure that it will be counted in the QOF.

System design

The design of any information system must address:

Data retrieval

It is essential that all relevant data are readily available both to the patient and to the involved healthcare professional. With the increasing use of audit for administrative (e.g. contracts) and clinical purposes, the speed and accuracy of retrieving data for analysis on an electronic system is seen to far outweigh the initial extra effort of data entry. The storage and retrieval of patient data must respect all the relevant legal requirements, in particular the Data Protection Acts. This is a minefield, and any practice is well advised to have in place clear policies and suitable training for all involved staff.

PHYSICAL PREMISES AND EQUIPMENT

PATIENT INFORMATION AND SUPPORT

Patient information may include:

Patients and their families may also benefit from support beyond that offered by their professionals. Patients (and families) who join Diabetes UK gain access to a confidential helpline, useful publications and various insurance and financial “products”; there are also better opportunities to meet other people with diabetes.

DELIVERING HIGH-QUALITY CARE TO OLDER PATIENTS WITH TYPE 2 DIABETES

Type 2 diabetes in the elderly may pose both clinical and logistical problems. With the growing number of older individuals, the prevalence of older diabetics will also increase significantly. Older diabetics are also more likely to request out-of-hours consultations and to need acute hospital admission (Tattersall & Page 1998).

Guidelines for the care of older diabetics have been published by the American Geriatric Society (Brown et al 2003) and the European Diabetes Working Party for Older People (Sinclair et al 2006). The latter suggests that “areas of clinical importance and targets for concerted action” in older diabetics should include:

OLDER POPULATION

Due to the increasing prevalence of diabetes with increasing age and to frequent asymptomatic presentation, clinicians need to have a lower threshold for considering the diagnosis and arranging appropriate screening. Although the OGTT is the ideal diagnostic test, a fasting plasma glucose may be a more feasible test, and an HbA1c greater than 7.5% may be useful if the individual is frail, demented or confined to a residential home (Greci et al 2003).

ASSESSMENTS

TREATMENT AIMS

Although glycaemic control is important in older diabetics, the greatest reduction in morbidity and mortality may result from some improvement in all modifiable cardiovascular risk factors. Treating hypertension in the elderly has been shown to be beneficial. There is less evidence for benefits of lipid modification and aspirin therapy; nevertheless, since all diabetics (especially the elderly) are at increased risk for developing CVD, these interventions are worth considering, unless contraindicated or in the very frail with limited life expectancy. Older diabetics who “are active, cognitively intact, and willing to undertake the responsibility of self-management should be encouraged to do so and be treated using the stated goals for younger adults with diabetes” (ADA 2007).

CARE HOMES

With increasing age, individuals are more likely to be house-bound or live in some form of residential or nursing home. The nature and quality of provision of diabetes care within residential care homes is variable. Among the potential or existing problems that may be encountered in these institutions are:

THE NEWLY DIAGNOSED PATIENT

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS TO BE ADDRESSED AT THE INITIAL CONTACT

Correction of elevated blood glucose begins at diagnosis. Using the “step-up” recommendations outlined in Table 3.3, the initial choice of diet alone, oral hypoglycaemic agents or insulin (if ketonuria is present) is based upon the following:

IMPORTANT AREAS TO ADDRESS FROM DIAGNOSIS

At or soon after diagnosis, three further areas will require attention:

IMMEDIATE ADMINISTRATIVE TASKS

The urgency of addressing these needs depends upon the patient’s circumstances and clinical status.

EARLY ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

The newly diagnosed type 2 patient requires an early full assessment to detect diabetes complications and cardiovascular risk factors, to identify any specific needs and to tailor management to these findings. This can be done either in the next available diabetic clinic session (if held regularly) or over a series of appointments. The components of the full periodic review are the basis of this assessment, which does need to be more comprehensive to establish a baseline. Additional information gathering will be dictated by the clinical situation. The structure of this assessment involves history, examination, investigations and administrative tasks (see Table 7.2), and will form the basis of the patient’s management plan. Optimal outcomes are more likely if the patient understands and agrees with the aims and methods. The familiar acronym RAPRIO (reassurance, advice, prescription, referral, investigations, observation) provides a useful framework to organise management interventions.

TABLE 7.2 Components of a full assessment of a newly diagnosed patient with type 2 diabetes

| History |

THE PERIODIC REVIEW: WHAT SHOULD IT CONTAIN?

Deciding what to include in the periodic review needs to take into account the following:

A suggested list of the essential components for a periodic review is given in Table 7.3. Accurate recording of what is measured is essential.

It is essential, if attempting to achieve optimal outcomes for diabetics, that patient-centred care is both delivered by appropriate members of the team and based upon a “structured, protocol-driven, multi-factorial approach” (Marshall & Flyvbjerg 2006). To avoid fragmenting care by focussing upon specific risk factors and/or complications to the exclusion of all relevant components, it is useful to remember the “Alphabet Strategy” (Lee et al 2004):

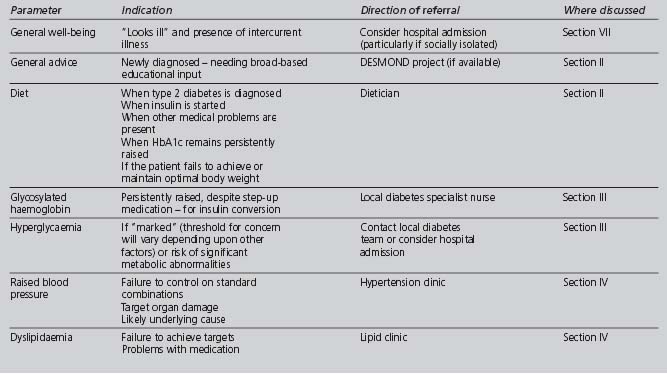

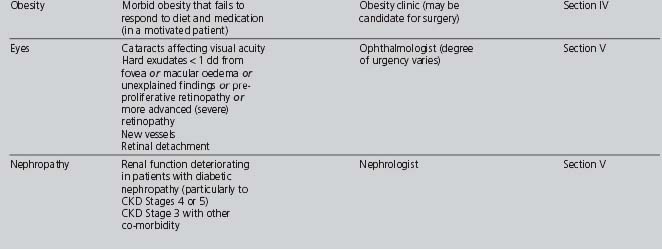

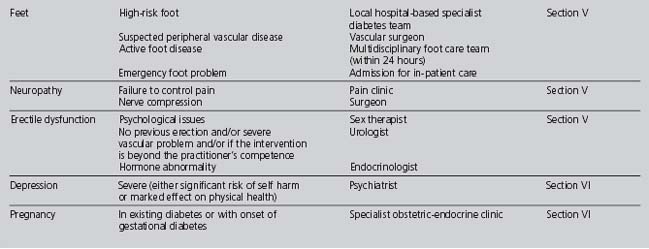

REFERRALS OUTSIDE THE PRIMARY HEALTHCARE TEAM

Although indications and mechanisms of referral to specialists (mainly secondary care) are discussed throughout the previous sections, a quick reference summary (not exhaustive) is provided in Table 7.4. Patient safety must remain paramount: clinicians should recognise the limits of their own competence and act accordingly.

MEASURING PERFORMANCE: AUDIT

WHAT IS AUDIT?

“Audit is the process of looking critically and systematically at our own professional activities with a view to improving personal/practice performance and the quality and/or cost effectiveness of patient care” (Fraser 1982). Guidance for undertaking clinical audit has been set out in Principles for Best Practice in Clinical Audit, published in March 2002 (NICE QUIDS 2002). Quality Indicators for Diabetes Services (QUIDS) has developed an audit methodology “appropriate for measuring the clinical quality performance of population based (primary and secondary care) routine, continuing diabetes care”. The final report commissioned by NICE, Diabetes UK and the NHS Executive Northwest, is now available (NICE CHI 2002) and complements the Diabetes Information Strategy.

STAGES OF CLINICAL AUDIT, AS APPLIED TO DIABETES CARE

1. Prepare for audit

TABLE 7.5 Aspects of diabetes care suitable for audit (Griffin & Kinmouth 1997)

| Criteria group | Suitable examples |

|---|---|

2. Select criteria

Standards are the percentage of events that should comply with the criterion (Baker 1995). If standards are set, they need to be agreed by the team, based upon relevant high-quality research evidence (if available) and realistic (current targets for glycaemic control, lipids and blood pressure are not always attainable). As the aim of the audit is to improve care, standards may be reset just above the predicted level of performance.

3. Measure performance

Identifying the study population

An accurate, up-to-date diabetic register enables the whole relevant population to be studied.

Ethical and legal implications

Data collection may have ethical and legal implications, especially in respect of confidentiality. The regulations set out in the Data Protection Act 1998 (HMSO 1997) must be followed. Professional bodies, such as the General Medical Council (General Medical Council 2000) and the Nursing and Midwifery Council, have issued relevant guidance.