20 The Orbit and Lacrimal System

ANATOMY OF THE ORBIT

The orbit is conical with a volume of approximately 27 ml. It contains the globe and the optic nerve, external ocular muscles, ophthalmic artery and its branches, orbital veins and nerves and the lacrimal gland. Orbital fat fills the remaining space and acts as a supportive cushion and fibrous septa run in planes between the ocular muscles and periosteum to support the orbital contents (see Ch. 18).

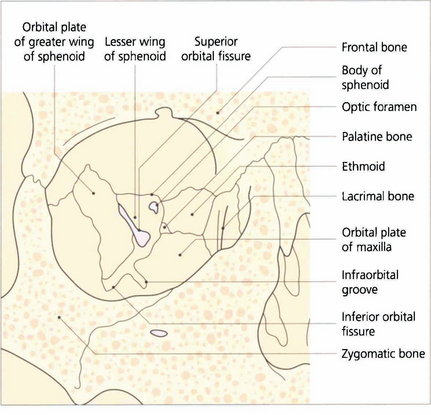

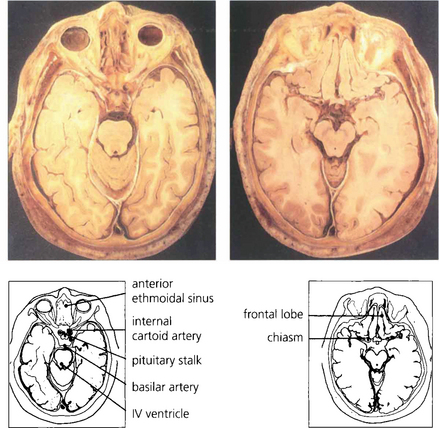

Fig. 20.1 Periosteum covers the orbital bones and adheres firmly at the anterior rim and at the apex around the optic canal. It is continuous with intracranial dura through the superior orbital fissure and optic canal. The lateral wall of the orbit is formed by the zygomatic bone and greater wing of the sphenoid. The frontal bone and part of the lesser wing of the sphenoid make up the roof. The fossa of the lacrimal gland lies superotemporally as a recess in the frontal bone, just above the junction with the zygoma. The floor is formed anteriorly by the maxillary process of the zygoma, centrally by the orbital plate of the maxilla and posteriorly by a small portion of the palatine bone. The infraorbital fissure lies between the greater wing of the sphenoid and the orbital plate of the maxilla and communicates with the pterygopalatine fossa posteriorly. The infraorbital groove carries the infraorbital nerve (Vb) and vessels. The medial wall is formed from anterior to posterior by the frontal process of the maxilla, the lacrimal bone (with the fossa of the lacrimal sac lying between), the ethmoid and the body of the sphenoid.

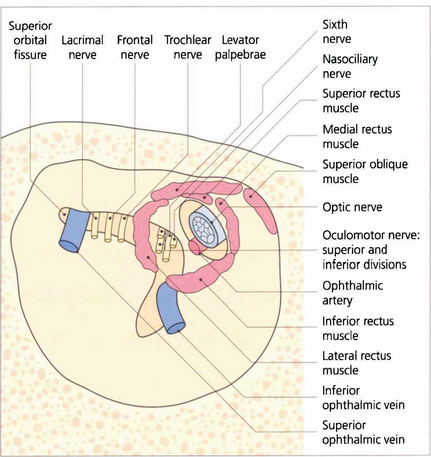

Fig. 20.2 The superior orbital fissure lies between the greater wing of the sphenoid inferiorly and the lesser wing superiorly (see Fig. 20.1). The lacrimal and frontal branches of the fifth nerve, the trochlear nerve and the superior ophthalmic vein are found superiorly and external to the annulus of Zinn; the superior and inferior divisions of the third nerve, the sixth nerve and nasociliary nerve lie within the annulus. The optic canal lies in the body of the sphenoid, medial and superior to the superior orbital fissure. It is lined with dura and transmits only the optic nerve and ophthalmic artery which lies inferior to the nerve. Space-occupying lesions at the orbital apex may compress the optic nerve and ocular motor nerves. Infiltrating lesions can spread through the superior orbital fissure into the cavernous sinus and middle cranial fossa to cause pain and loss of sensation in the distribution of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. The sphenoidal sinus lies medial to the optic canal and the two are separated by extremely thin bone, which may even be absent, so that the optic nerve is easily damaged by surgery or disease within the sphenoidal sinus.

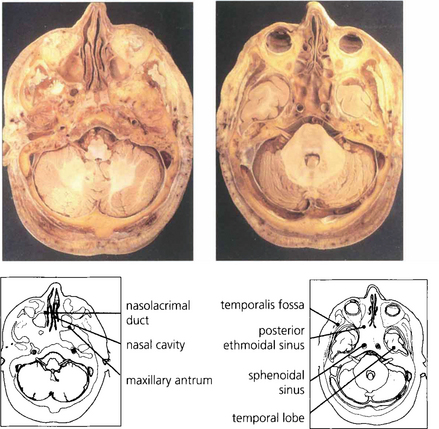

Fig. 20.3 The middle cranial fossa and temporal lobes lie posterior to the orbit and are separated from it by the sphenoidal wings. The temporalis muscles and fossa lie laterally and the maxillary sinus lies inferomedially.

Fig. 20.4 Anatomical sections enable a clear correlation to be made between the orbital anatomy and the computed tomography (CT) appearance. Note the close relationship of the frontal lobes to the orbital roof, the anterior and posterior ethmoidal sinuses to the medial orbital wall and the sphenoidal sinus to the optic canal.

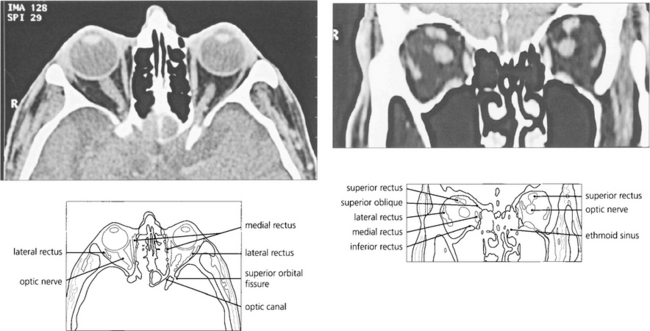

Fig. 20.5 CT scanning still has advantages over magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the orbit as the bony anatomy and calcification (an important sign of many pathological processes) is readily seen on CT. Axial scans taken along the line joining the external auditory meatus and inferior orbital rim cut the globe through the lens, optic nerve and optic canal in a single plane. The superior orbital fissure can be mistaken for the optic canal, which lies medially and superiorly, adjacent and medial to the anterior clinoid process. The optic nerve has a sinuous course within the orbit and cannot always be seen on a single cut if the section is thin. Similarly, partial sections of the ocular muscles may resemble a space-occupying mass at the apex if the scan is not interpreted carefully. Coronal scans are frequently much more informative and easier to interpret.

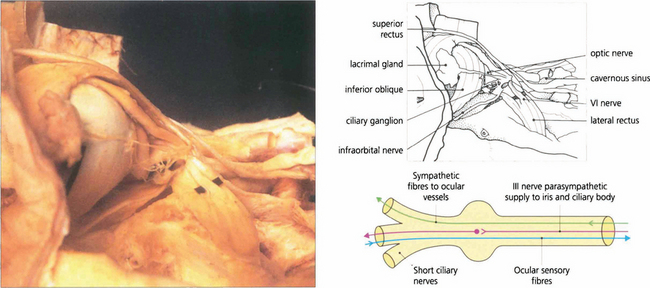

Fig. 20.6 A dissection of the lateral aspect of the orbit shows the orbital lobe of the lacrimal gland and its nerve. The lateral rectus muscle and sixth nerve are retracted to demonstrate the ciliary ganglion and short ciliary nerves. The ciliary ganglion (b) contains not only the synapses of the parasympathetic fibres to the iris and ciliary body from the third nerve, but also the efferent (and nonsynapsing) sympathetic fibres to the ocular blood vessels. Afferent sensory fibres from the cornea, iris and ciliary body pass through the ganglion to the nasociliary branch of the ophthalmic nerve.

ORBITAL BLOOD SUPPLY

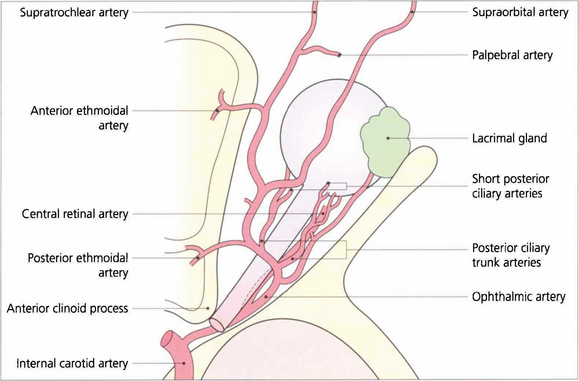

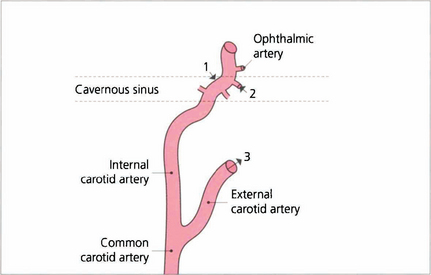

Fig. 20.7 The ophthalmic artery arises from the internal carotid artery immediately above the cavernous sinus and enters the orbit through the optic canal inferior to the optic nerve. It then passes laterally and superiorly over the optic nerve to give branches to the lacrimal gland and ocular muscles. The ophthalmic artery continues anteriorly and leaves the muscle cone to anastomose with branches of the external carotid artery in the lids, face and scalp. These anastomoses are of clinical importance if the internal carotid system is occluded.

The two posterior ciliary arteries leave the ophthalmic artery inferior to the optic nerve at the orbital apex. They pass forwards and divide before entering the globe around the optic nerve as several short posterior ciliary branches to supply the optic nerve head, retrolaminar optic nerve and choroid. The central retinal artery also arises from the ophthalmic artery and passes forwards and inferior to the optic nerve, to penetrate the nerve some 10–12 mm posterior to the sclera (see Ch. 17).

Fig. 20.8 The vortex veins from the choroid drain into the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins which flow into the cavernous sinus posteriorly and the pterygopalatine plexus inferiorly. Apsidal veins join the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins in the orbit. Anteriorly the orbital veins communicate with the frontal vein draining the scalp to form the facial vein which then drains into the external jugular vein. Orbital veins do not have valves and the intracranial and extracranial venous systems communicate freely explaining the facility with which infection can spread intracranially from the orbit. A distended superior orbital vein is seen as a neuroradiological feature of caroticocavernous fistulas

Adapted from Snell RS, Lemp MA. Clinical Anatomy of the Eye. ©1989 Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publishers.

| Children | Adults |

|---|---|

| Orbital cellulitis | Trauma |

| Dermoid and epidermoid cysts | Thyroid eye disease |

| Capillary haemangioma and lymphangioma | Idiopathic orbital inflammatory disease (formerly known as ’pseudotumour’) |

| Neurofibroma* | Lacrimal gland inflammation and tumours |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma* | Cavernous haemangioma |

| Optic nerve glioma* | Varices and lymphangioma |

| Leukaemia* | Lymphoma and lymphoproliferative disease |

| Meningioma (optic nerve or sphenoid wing) | |

| Metastases |

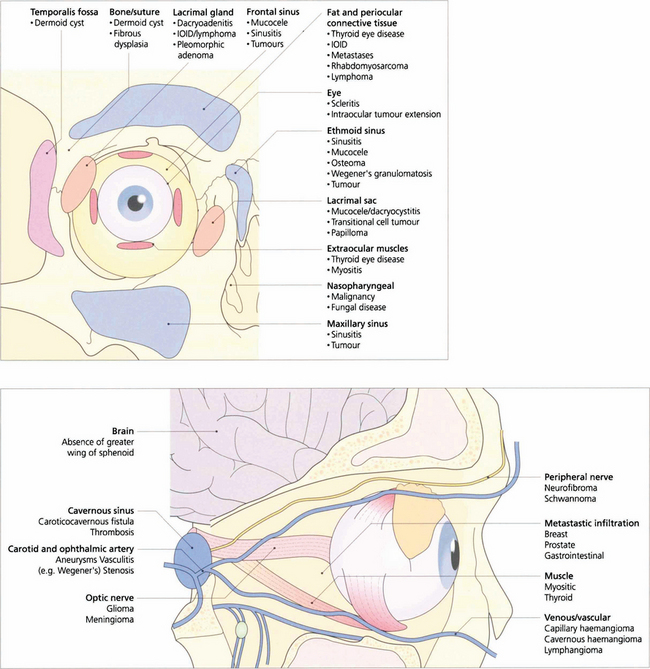

CAUSES OF ORBITAL DISEASE

Fig. 20.9 Orbital disease may arise from abnormalities of the normal constituents of the orbit, contiguous spread of disease from adjacent structures, or invasion from haematogenous spread.

EXAMINATION OF THE ORBIT

Proptosis must be distinguished from pseudo-proptosis due to enlargement of the globe, congenital bony deformity or facial asymmetry, enophthalmos of the fellow eye and lid disease such as retraction. Ptosis will occasionally present as ‘proptosis’ of the contralateral eye (see Ch. 2).

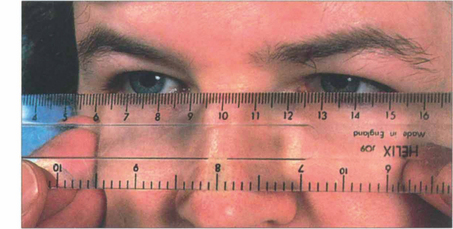

Fig. 20.10 The degree of proptosis is measured with an exophthalmometer. The feet of the instrument are placed on each bony lateral orbital margin and the distance between the feet (i.e. the distance between each lateral orbital rim) is recorded for future comparison. The eye of the patient and that of observer are aligned, corrected for parallax (the fellow eye must be occluded if a strabismus is present) and the degree to which the corneal apex protrudes in front of the lateral orbital margin is recorded. Protrusion of the corneal apex varies with facial anatomy and so there is no absolute normal value of proptosis although asymmetrical proptosis of 2 mm or more is usually considered significant.

Fig. 20.11 Variation in ocular position and pulsatile proptosis should be sought where appropriate. Proptosis is axial if displacement is along the visual axis and nonaxial if displacement is off the visual axis. This can be judged by placing a clear plastic rule horizontally across the bridge of the nose to measure the horizontal and vertical positions of the visual axis of each eye. The fellow eye should be occluded when strabismus is present.

ACUTE PROPTOSIS

Fig. 20.12 Acute orbital cellulitis presents with fever and malaise, pain, proptosis, restriction of eye movements and conjunctival injection and oedema. This girl has an acutely swollen and painful left upper lid with the globe depressed from cellulitis in the superior part of the orbit secondary to a frontal sinusitis. Patients require hospital admission, nasal and blood cultures and intravenous antibiotics. These should not be delayed for investigations such as imaging. An orbital or subperiosteal abscess generally requires surgical drainage.

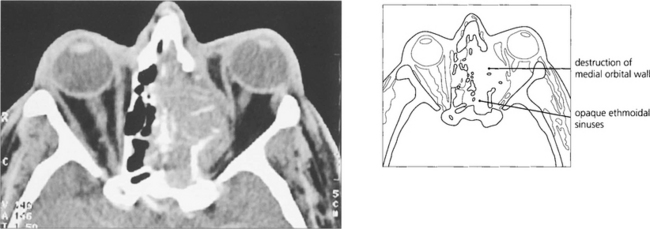

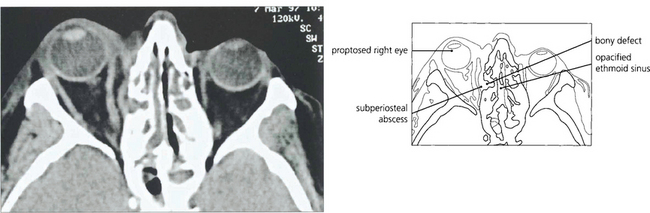

Fig. 20.13 CT scan from another patient showing an infective extension from the ethmoidal sinus into the orbit with a small subperiosteal abscess elevating the periosteum.

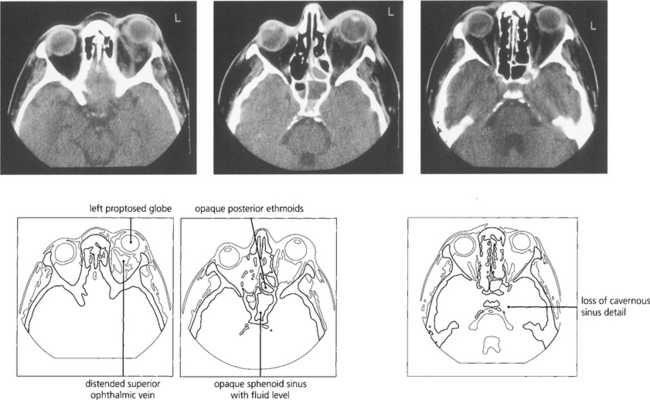

Fig. 20.14 Cavernous sinus thrombosis is now a rare complication of orbital cellulitis but must be considered when clinical signs progress rapidly with associated meningism, ocular motor and pupillary palsies, and signs of acute inflammation in the cerebrospinal fluid. MRI shows the thrombosis in the cavernous sinus better than CT.

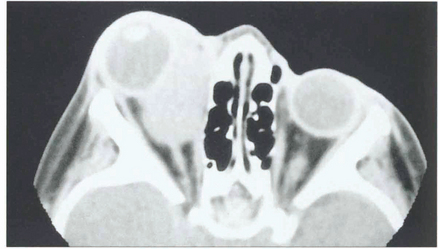

Fig. 20.15 Embryonal sarcomas are tumours of mesenchymal cells with the potential to differentiate into striated muscle (striated or nonstriated rhabdomyomatous differentiation). They are commonly known as rhabdomyosarcomas although they do not arise from striated muscle. They are the commonest primary orbital malignancy of childhood. They can grow very rapidly; this child’s proptosis increased almost daily.

Fig. 20.16 CT scan showing a mass in the region of the medial rectus. After diagnostic biopsy treatment with radiotherapy and chemotherapy carries an excellent prognosis provided the tumour is confined to the orbit. These lesions can invade the orbital walls and metastasize haematogenously to the lung, lymph nodes and bone marrow.

CHRONIC AXIAL PROPTOSIS

THYROID EYE DISEASE

The commonest cause of axial proptosis is thyroid eye disease which can affect the orbits symmetrically or asymmetrically, with the latter producing apparently uniocular proptosis. Patients may be hypothyroid, euthyroid or hyperthyroid. T3, T4 and thyroid autoantibodies should be measured in all patients but about 15 per cent of patients have completely normal findings; in these patients the diagnosis is made clinically and by CT. Patients should be assessed for cosmesis, corneal exposure, diplopia and optic nerve involvement, all of which may occur independently of each other. Patients may have sore, irritable or watery eyes from exposure keratopathy, superior limbic keratitis (see Ch. 5) or disturbance of tear film metabolism. Smoking has been shown to be a significant risk factor for the development of dysthyroid eye disease which may also deteriorate at the time of treatment of hyperthyroidism with I131.

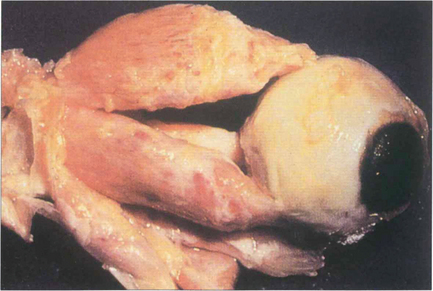

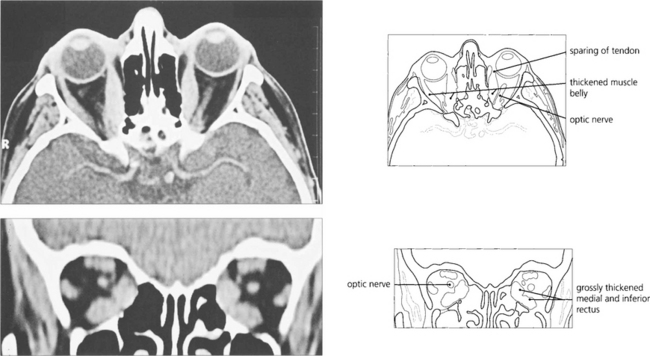

Fig. 20.17 Pathologically, dysthyroid eye disease affects the external ocular muscles rather than their tendinous insertions in contrast to idiopathic myositis. In the early stage inflammatory cells infiltrate the muscle belly causing oedema; as the disease progresses, collagen and glycosaminoglycans are produced by endomysial fibroblasts. Chronically, the muscles become fibrotic from contraction of the collagen and infiltrated by fat and may be expanded by up to eight times their normal size.

By courtesy of Dr R Eagle.

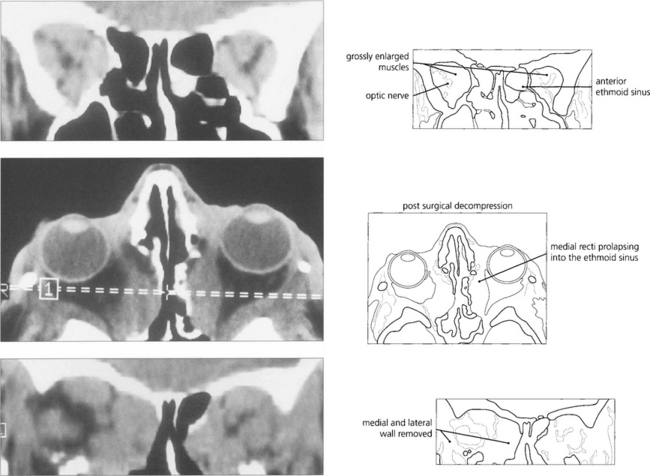

Fig. 20.18 Axial and coronal CT scans demonstrate thickening of the extraocular muscles. The medial and inferior recti are preferentially involved. Note that the muscle tendons are spared.

Fig. 20.20 Symmetrical and inactive (‘burnt-out’) thyroid eye disease. This patient has bilateral proptosis, and upper and lower lid retraction. Upper eyelid retraction is attributed to excessive sympathetic stimulation of Müller’s muscles and fibrosis of the levator complex.

Fig. 20.21 Asymmetrical orbital involvement is extremely common. Dysthyroid eye disease is common in young women. The cosmetic aspects of the disease cannot be overemphasized.

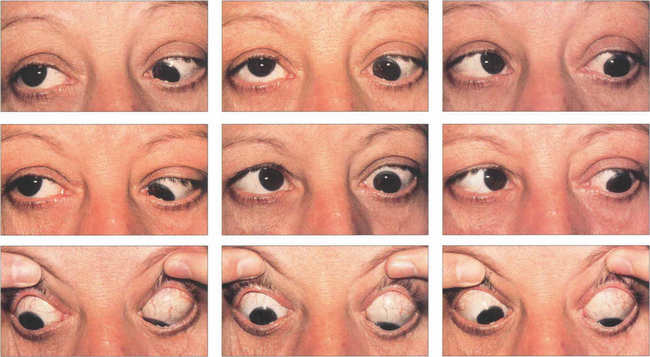

Fig. 20.22 Dysthyroid eye disease preferentially affects the inferior and medial recti, typically producing tethering of the globes in upgaze and convergence. This patient shows limitation of all ocular movements except left downgaze. Elevation of both eyes is affected, left more than right. She is convergent in primary gaze with a right over left hypertropia; abduction of both eyes is limited, the left more than the right, from tethering by the medial recti.

Fig. 20.23 Corrective muscle surgery is contraindicated until the diplopia has stabilized. Repeated monitoring of the ocular movements with Hess charts or fields of BSV are very useful in monitoring progress (see Ch. 18). Temporary Fresnel prisms give symptomatic relief until the patient is ready for definitive surgery.

Fig. 20.24 This patient shows conjunctival and some corneal exposure when gently closing her eyelids, as in sleep. With chronic disease the lids often compensate to some extent but the patient may have considerable problems with watering and discomfort of the eyes from night time exposure.

Fig. 20.25 Acute proptosis and orbital congestion can lead to corneal exposure and ulceration as well as optic neuropathy. High dosage of intravenous steroids can help in the short term to reduce proptosis but in severe cases urgent surgical orbital decompression is required to save the eye.

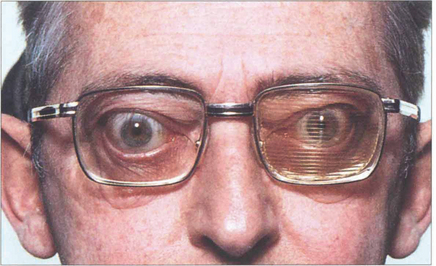

Fig. 20.26 Enlarged muscle bellies cram the orbital apex and cause optic nerve compression, especially in patients with minimal proptosis; those with gross proptosis tend to ‘decompress’ their own orbits. Decreasing acuity, colour loss, afferent pupillary defect and a central scotoma suggest optic nerve compression. The optic disc may be swollen, normal or atrophic. Many patients respond to systemic steroids but orbital decompression is indicated if the optic nerve compression is unrelieved. Intraorbital tension can be assessed by gently ballotting the globes against the retrobulbar fat.

Fig. 20.27 Coronal scans show gross muscle hypertrophy crowding the orbital apex and causing optic nerve compression. Axial and coronal scans show the postoperative appearances following decompression of both orbits into the ethmoidal and maxillary sinuses and removal of the lateral wall relieving orbital apical congestion.

ORBITAL VARICES

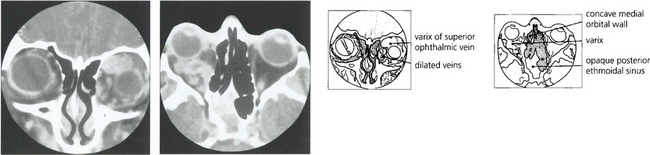

Fig. 20.28 Variable proptosis of the right eye is demonstrated in this patient. On a Valsalva manoeuvre the right eye becomes proptosed with ptosis of the upper lids due to increased pressure in the malformation. Varices consist of ectatic vascular channels or a segmentally dilated vein there can rarely thrombose or bleed spontaneously causing acute painful proptosis.

CAROTICOCAVERNOUS FISTULAS

The clinical presentation depends on the rapidity of onset, extent of vascular shunting and increased orbital venous pressure and consequent orbital or ocular hypoxia. High-flow shunts present with proptosis which may be bilateral and asymmetrical due to communication with the contralateral cavernous sinus, external ophthalmoplegia with orbital ischaemia from shunting, and high venous pressure. Visual loss is caused by optic nerve or intraocular ischaemia, rubeosis iridis may be seen and patients may complain of a bruit. Low-flow shunts may present as a glaucomatous eye with arterialized and engorged conjunctival vessels (see Ch. 8).

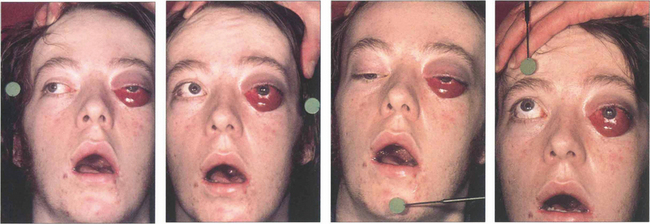

Fig. 20.31 High-flow fistulas result from traumatic tears of the internal carotid artery in the cavernous sinus (1). Fistulas may result from communication between the branches of the internal carotid artery with the cavernous sinus; these are usually low flow (2). Dural fistulas result from branches of the external carotid artery communicating with the cavernous sinus through dural shunts. These are also low flow (3). Fistulas frequently have multiple communications. A combination of 2 and 3 is the commonest. Low-flow fistulas may occasionally result from excessive straining (e.g. childbirth) and sometimes close spontaneously.

Fig. 20.32 This patient suffered a severe head injury and fracture of the base of the skull in a motorcycle accident. His asymmetrical proptosis was greater in the left eye and associated with a total ophthalmoplegia of the left eye and partial ophthalmoplegia of the right eye. Pulsating exophthalmos and an audible bruit were present indicating a high-flow fistula. The conjunctiva of the left eye was chemotic and its veins engorged. The eye was blind and there were signs of ocular hypoxia with a dilated, unreactive pupil. The right eye had normal visual acuity. Intraocular pressure on the side of the fistula was higher with a larger pulse amplitude which can help in diagnosing cases with low flow and mild signs.

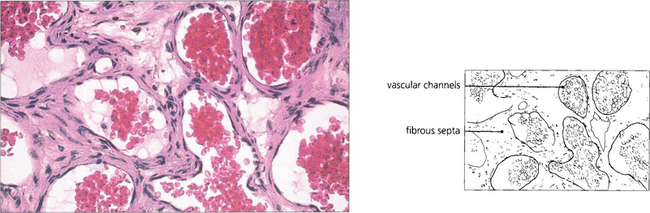

Fig. 20.33 CT shows proptosis and dilatation of the superior ophthalmic vein, a consistent finding in caroticocavernous fistulas. Carotid angiography of the same patient demonstrates a massive fistula in the region of the cavernous sinus that was treated successfully by embolization using a balloon catheter technique. The patient’s chemosis, proptosis and ocular movements improved but the vision did not.

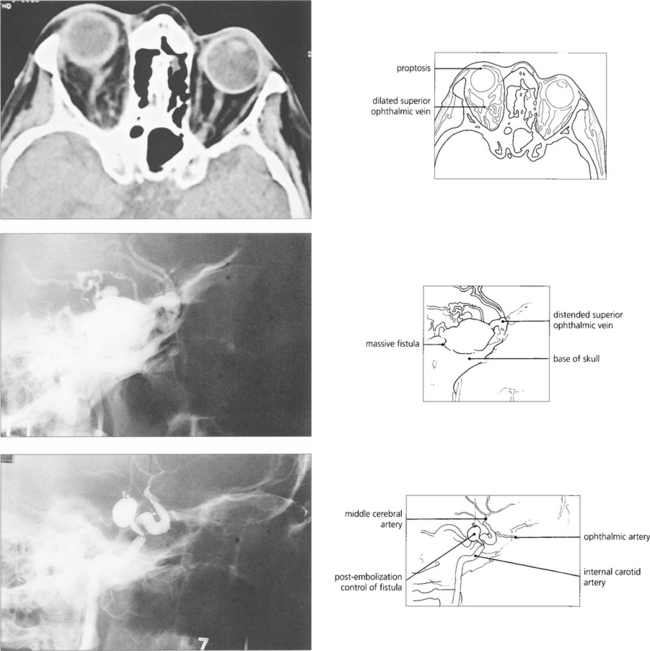

CAVERNOUS HAEMANGIOMA

Fig. 20.34 CT shows a typical haemangioma as a well defined mass that is distinct from the globe and optic nerve. Blood flow through the lesion is sluggish and explains why lesions enhance slowly and patchily following injection of contrast. The lesion was removed intact through a lower-lid swinging flap.

OPTIC NERVE GLIOMAS

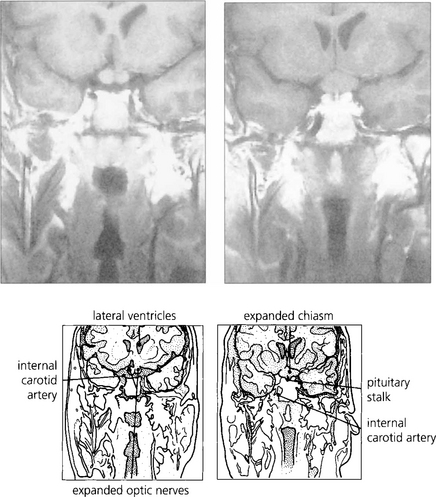

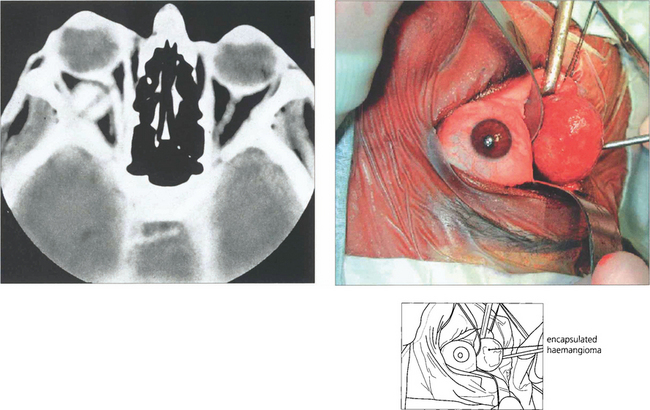

Fig. 20.36 The neuroradiological appearances are characteristic. MRI shows an enlarged orbit with a smooth fusiform enlargement of the optic nerve.

MENINGIOMAS

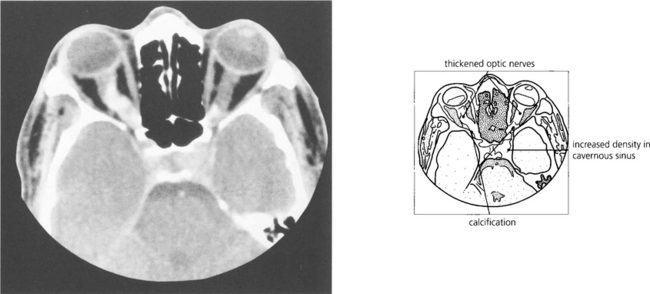

Fig. 20.39 CT characteristically shows tubular thickening of the optic nerve with areas of calcification with minimal proptosis. Bilateral optic nerve involvement is well recognized, as in this patient; note that the left cavernous sinus is expanded by tumour. MRI with contrast enhancement is necessary to determine the extent of intracranial involvement.

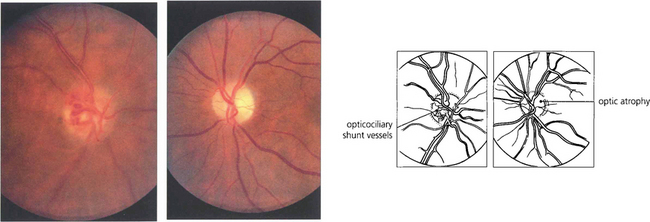

Fig. 20.40 Slow strangulation of the optic nerve produces chronic disc oedema followed by optic atrophy. Fundus photographs of the same patient show opticociliary collateral vessels (shunting blood from the obstructed central retinal vein to the choroidal circulation) in the right eye and optic atrophy in the left. Occasionally, aggressive meningiomas may even invade the optic disc.

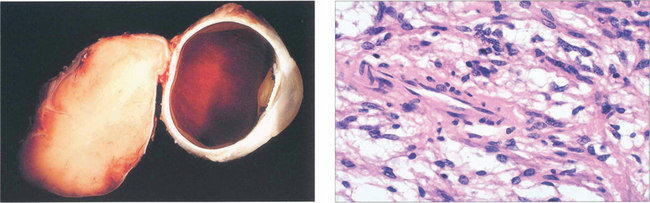

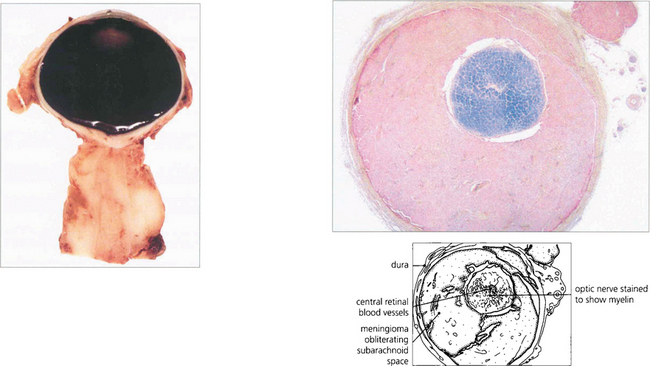

Fig. 20.41 This pathological specimen shows a meningioma surrounding the optic nerve. In adults the tumour is locally invasive but slow growing. Limited surgical exploration may risk spreading the tumour into the orbit and indolent tumours are best either watched or completely excised; both types of treatment have their protagonists. Radiotherapy may be considered for aggressive recurrent tumours.

Left figure by courtesy of Dr M P Carey.

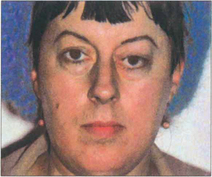

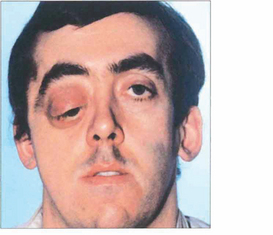

Fig. 20.42 Sphenoidal ridge meningiomas typically occur in middle-aged women. They are slow growing over many years and produce painless proptosis from infiltration and thickening of the orbital walls. This woman shows proptosis with the globe displaced inferiorly and swelling of the left temporal fossa which is a characteristic feature of temporal bone involvement.

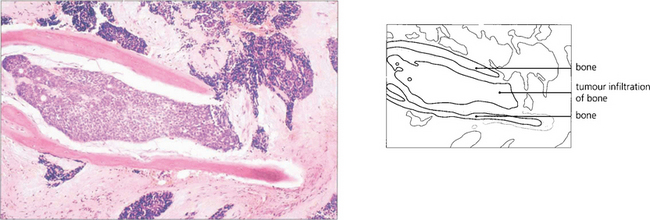

Fig. 20.43 The meningioma usually originates on the greater wing of the sphenoid and infiltrates the bone producing thickening and sclerosis (as shown on this CT). Optic nerve compression occurs when the tumour affects the optic canal, and motility when it spreads into the cavernous sinus. MRI is necessary to evaluate intracranial spread fully. Surgical removal is unsatisfactory and produces further visual loss or ocular motor nerve damage.

IDIOPATHIC ORBITAL INFLAMMATORY DISEASE AND ORBITAL APEX SYNDROME

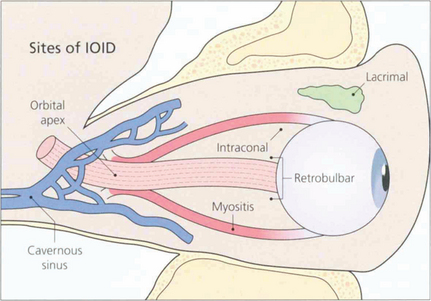

Fig. 20.44 IOID is uncommon and may occur anywhere in the orbit such as in the lacrimal gland, intraconal space, external ocular muscles or orbital apex. Presentation is usually acute or subacute and pain is an important feature; depending on the location there may be acute proptosis, chemosis, motility disturbance or visual deterioration. A few present as chronic, painless space-occupying lesions. The orbital apex is a common site for IOID and produces a characteristic syndrome of painful proptosis and visual loss with third, fourth, fifth and sixth nerve palsies (the ‘orbital apex syndrome’). Lesions found slightly more posteriorly in the cavernous sinus produce the same signs but without visual loss.

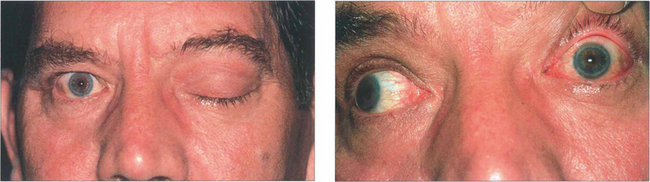

Fig. 20.45 This middle-aged man presented with painful proptosis and complete ptosis coming on over a few days. There was complete left ophthalmoplegia from third, fourth and sixth nerve palsies. The close-up photograph (b) shows the ocular motor paresis with the patient attempting to look right. Note the conjunctival injection. Sparing of the pupil with the third nerve palsy is due to a concomitant Horner’s syndrome. Visual acuity was reduced to 20/100. Colour perception was decreased in the left eye and there was a left relative afferent pupillary defect with a relative central scotoma in the visual field. The optic disc appeared normal.

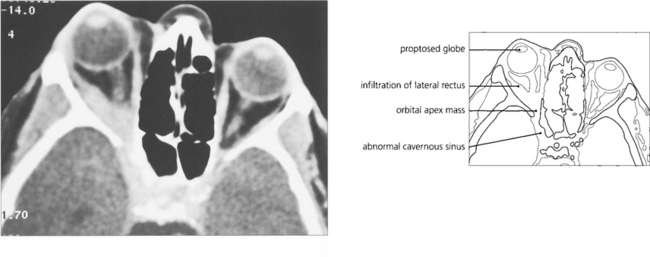

Fig. 20.46 CT shows proptosis with an orbital apex mass extending forwards into the lateral rectus and posteriorly through the superior orbital fissure into the cavernous sinus. MRI would be necessary to discern the degree of cavernous sinus involvement.

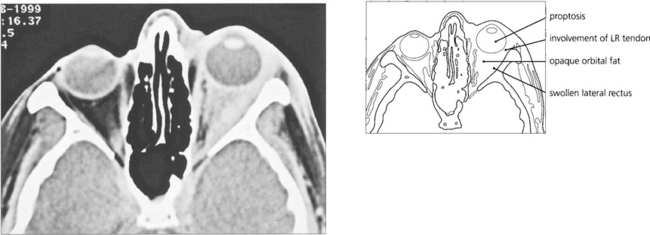

Fig. 20.47 This 37-year-old radiologist presented with horizontal diplopia worse on left gaze with pain and proptosis. The scan shows a thickened lateral rectus with involvement of the tendon characteristic of myositis. The adjacent orbital fat is involved with mild proptosis. The patient was treated with steroids; failure to make a full and rapid clinical recovery requires biopsy to exclude other pathology.

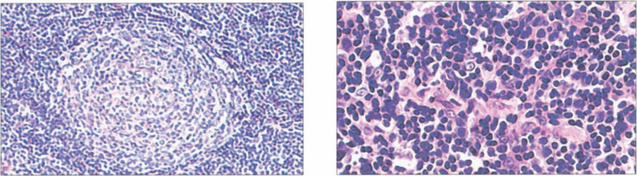

Fig. 20.48 A range of pathology may be seen in IOID. Germinal follicle formation (left) is a feature of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, a benign lesion that will respond satisfactorily to steroid therapy or even resolve. Lymphomas (right) also show a lymphoid infillrate. Many lesions are difficult to classify without immunohistological techniques which are necessary for accurate diagnosis. Monoclonal immunoglobulin expression is indicative of malignancy, but 15–20 per cent of patients with polyclonal tumours eventually develop lymphoma.

CHRONIC NONAXIAL PROPTOSIS

DERMOID CYST

Fig. 20.49 A dermoid cyst in the superior part of the orbit displaces the right globe inferiorly. The patient was referred as having a right ‘ptosis’ without diplopia. The other child has a more superficial dermoid cyst presenting as a lump in the upper lid.

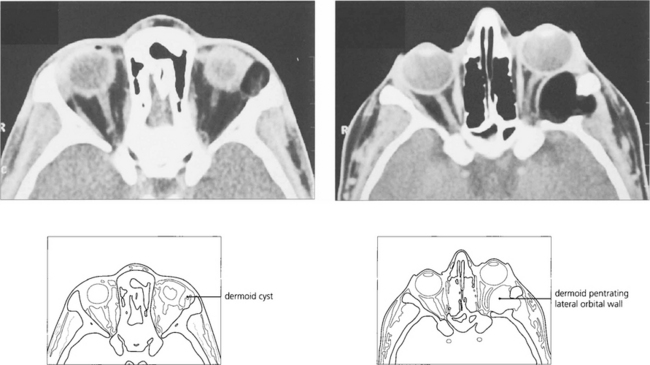

Fig. 20.50 Slow expansion of the cyst produces a bony skull defect with a sharp sclerotic margin readily seen on CT. Dermoid cysts must be evaluated and excised with care as they may occasionally penetrate through to the dura to require a combined neurosurgical excision. Partial excision must be avoided as the remnants produce chronic inflammation with a discharging sinus.

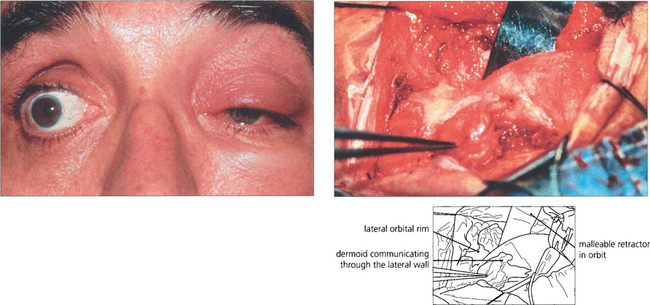

Fig. 20.51 The oily sebaceous contents of a dermoid cyst can leak and cause a lipogranulomatous reaction and acute cellulitis. In this patient inflammation improved after 2 weeks of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy. At operation the dermoid is dumb-bell shaped, communicating through a hole in the bone.

NEUROFIBROMATOSIS (VON RECKLINGHAUSEN’S DISEASE)

Neurofibromatosis (NF) is two separate diseases. NF1 is the commoner type with the well recognized cutaneous stigmata of café-au-lait spots, neurofibromas and Lisch nodules on the iris (see Chs 2 and 9). The gene is located on chromosome 17, has an incidence of 1 in 3000 live births and a dominant inheritance with high penetrance but variable expressivity; new mutations are common. There is a wide variation in the disease spectrum between patients and within families. The gene for NF2 is located on chromosome 22 and is much rarer with an incidence of 1 in 40,000. It is dominantly inherited and is characterized by bilateral acoustic neuromas (see Ch. 17). Café-au-lait spots and neuro-fibromas are less prominent than in NF1. Lisch nodules can occur in both conditions. Patients with NF1 tend to develop neural or astrocytic tumours such as astrocytomas or gliomas, whereas those with NF2 develop tumours of nerve sheaths and coverings such as schwannomas and meningiomas.

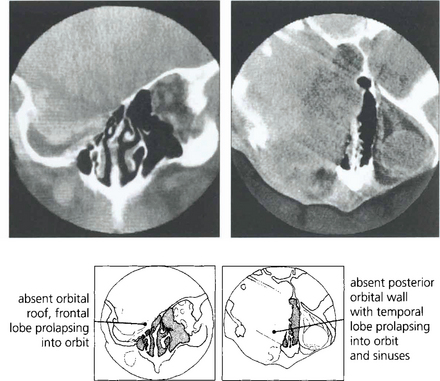

Fig. 20.52 Neurofibromatosis is sometimes associated with orbital bony malformations, particularly absence of the greater and lesser wings of the sphenoid. In this case the intracranial contents of the middle fossa (temporal lobe) lie directly in contact with the orbit and produce a characteristic pulsating proptosis from the transmitted cerebral pulse wave.

LACRIMAL FOSSA LESIONS

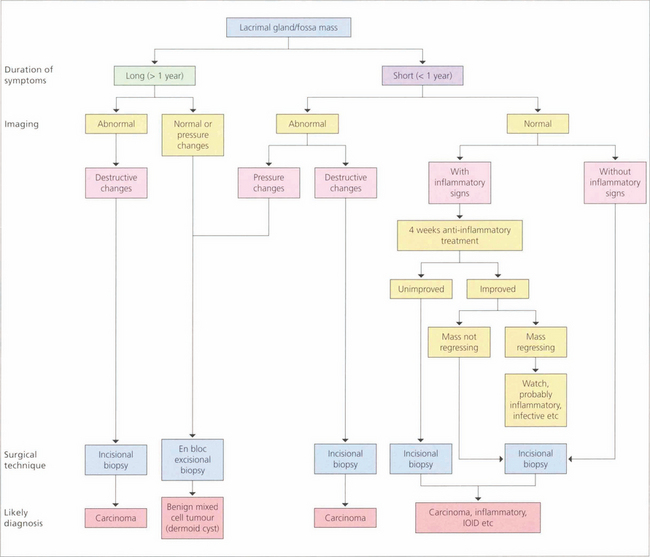

Fig. 20.54 Flow diagram of the differential diagnosis of lacrimal fossa masses based on the duration of symptoms and findings on imaging helps to provide a clinical diagnosis. Pleomorphic adenomas (benign mixed tumours) occur in adults aged 20–60 years and are characterized by a slow, painless, progressively enlarging, lacrimal fossa lesion that has usually been present for at least a year before presentation. A mass can be palpated and CT may show diffuse enlargement of the lacrimal fossa without bony invasion. These lesions must be excised en bloc by lateral orbitotomy as biopsy or partial excision leads to local recurrence with invasion of the surrounding structures and a potentially fatal outcome. Carcinomas characteristically have a short progressive history of less than 1 year and are painful; CT may show bony invasion or calcification within the tumour. Diagnosis is made by biopsy with the option of debulking and radiotherapy. Patients with lacrimal gland carcinomas tend to have a poor prognosis. Other causes of lacrimal fossa masses are viral adenitis (e.g. mumps), inflammatory granulomas (sarcoid), IOID or dermoids.

Fig. 20.55 This elderly patient had a painless long-standing mass in the lacrimal fossa with the globe displaced medially and downward, as is typical of a pleomorphic adenoma. A close-up photograph demonstrates the swelling more clearly (b).

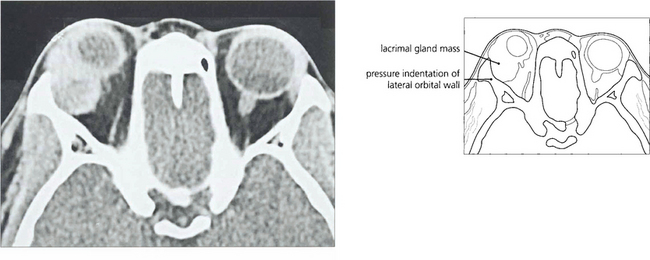

Fig. 20.56 CT showed an enlarged lacrimal fossa and solid mass typical of a pleomorphic adenoma (which is to be distinguished from a dermoid cyst that looks cystic) with a sharp sclerotic bony margin.

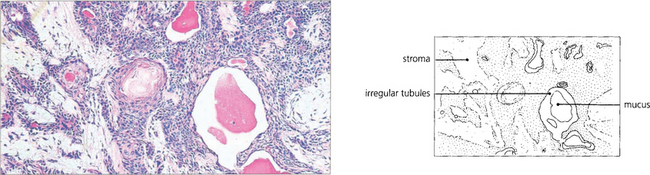

Fig. 20.57 The histological appearance of a typical pleomorphic adenoma varies considerably within itself. Epithelial and myoepithelial cells proliferate and glandular and myxoid tissues are seen. Irregular epithelial lined tubules contain mucus and keratin; the myxoid stroma may contain fat and cartilage. There is a pseudocapsule which is often penetrated by nodules of tumour tissue that lead to local recurrence if excision is complete.

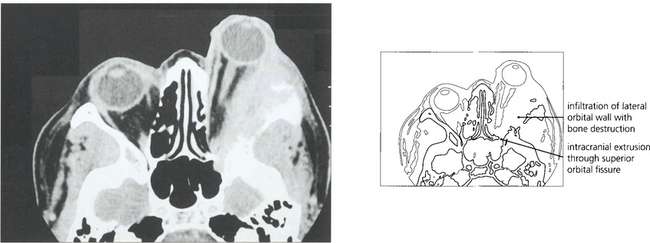

Fig. 20.58 In contrast to a benign mixed tumour, this girl has an adenoid cystic carcinoma that presented with pain in the right lacrimal fossa area and a palpable mass which had been present for a few months.

MEDIAL WALL ORBITAL LESIONS

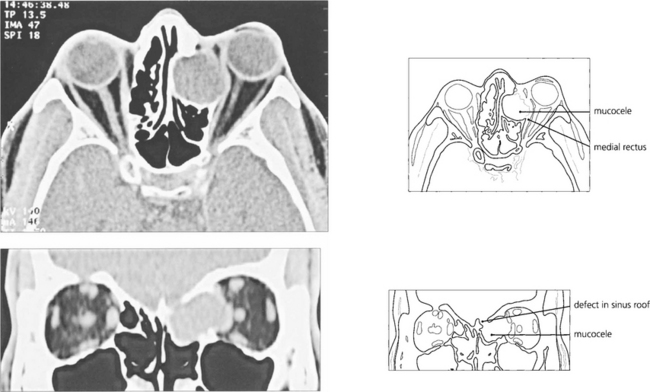

Fig. 20.61 An ethmoidal mucocele causes globe displacement. The absence of orbital inflammation is demonstrated by the normal dark signal of the orbital fat; compare this to the ‘dirty’ fat signal of IOID (see Fig 20.47).

Fig. 20.62 These two patients have carcinomas of the ethmoidal sinus. The globe is displaced laterally in the younger man (left), whereas the base of the nose is expanded in the older man (right). Because symptoms are initially nonspecific (nasal discharge, bleeding, etc.), patients with paranasal sinus carcinomas tend to present late and consequently have a poor prognosis.

ORBITAL TRAUMA

A blunt injury to the globe can increase intraorbital pressure to produce a ‘blow-out’ fracture into the maxillary or ethmoidal sinuses (see Ch. 18).

Fig. 20.64 This patient presented with no perception of light in the right eye following a gardening accident in which she poked the end a fine cane support into the right eye as she bent over. Closer examination showed a conjunctival laceration over the medial aspect of the globe. The tip of the cane displaced the globe laterally and travelled medially along the orbital wall to transect the optic nerve at the orbital apex. The right pupil has been dilated for diagnostic purposes.

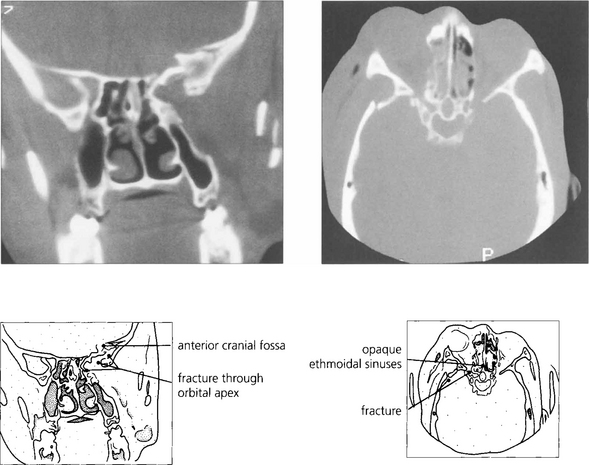

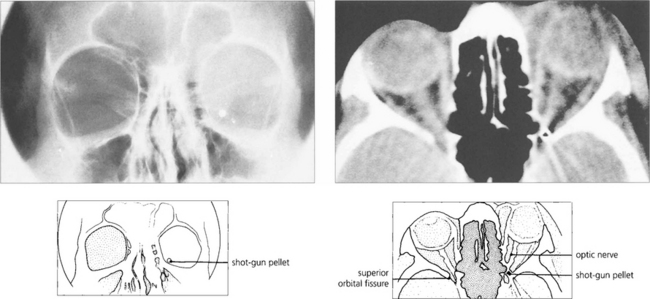

Fig. 20.65 CT and skull radiography show a shotgun pellet lodged in the left orbital apex following a sporting accident. The patient had an inferior altitudinal field loss in the affected eye that remained unchanged on subsequent examinations. Surgical removal of the pellet is contraindicated as this is likely to cause further visual loss.

THE LACRIMAL DRAINAGE SYSTEM

Outflow obstruction may be at the level of the punctum, canaliculi, nasolacrimal sac or nasolacrimal duct. Accurate evaluation of the cause of epiphora is essential to implementing appropriate treatment. (Dry eyes are discussed in Ch. 5.)

Fig. 20.68 Innervation of the lacrimal gland. Parasympathetic fibres arise in the lacrimal nucleus, which is part of the superior salivatory nucleus just caudal to the seventh nerve nucleus in the floor of the fourth ventricle. Leaving the brain in the nervus intermedius they pass without synapse through the geniculate ganglion to the greater superficial petrosal nerve, running forwards in a groove on the floor of the petrous temporal bone. At the foramen lacerum they are joined by sympathetic fibres of the deep petrosal nerve from the carotid plexus to form the nerve of the pterygoid canal (vidian nerve). The lacrimal secretory fibres synapse in the sphenopalatine ganglion and join the zygomaticotemporal branch of the maxillary nerve. This nerve passes through a foramen in the lateral orbital wall to join the lacrimal branch of the ophthalmic division of V in the orbit to supply the lacrimal gland. Crocodile tears are due to aberrant innervation of the lacrimal gland by misdirected secretomotor fibres from the superior salivary nucleus producing epiphora in response to stimulation of taste. It can occur congenitally or with acquired lesions of the facial nerve proximal to the geniculate ganglion.

Adopted from Bron et al. Wolff’s Anatomy of the Eye and Orbit. ©1997 London: Hodder Arnold Publishers.

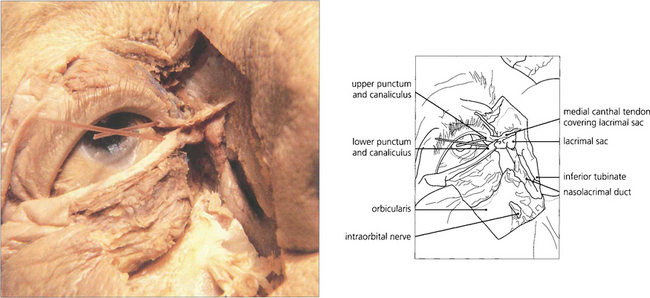

Fig. 20.69 A cadaver dissection shows the medial palpebral ligament lying anteriorly to the canaliculi. The orbicularis has been excised to show the lacrimal sac and the nasolacrimal duct passing downwards through the maxilla to enter the nasal cavity under the inferior turbinate. Mucosal flaps within the nasolacrimal duct act as valves and prevent retrograde air entry into the lacrimal sac.

By courtesy Dr Ted Garway Heath.

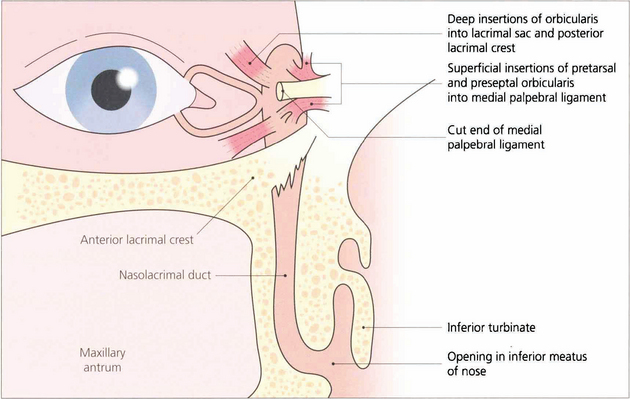

Fig. 20.70 A diagram shows the anatomy in more detail. The upper and lower puncta enter the canaliculus as a short vertical passage that turns medially in the lid margin. The canaliculi have a length of about 8 mm. They anastomose to form the common canaliculus which opens by a single orifice into the lateral wall of the lacrimal sac. Palpebral fibres from the orbicularis oculi muscle are inserted superficially into the medial palpebral ligament and deeply into the lacrimal fascia surrounding the fundus of the sac. The nasolacrimal duct has an intraosseus length of approximately 12 mm and opens into the inferior meatus of the nose.

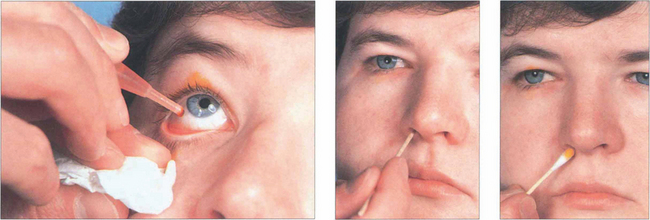

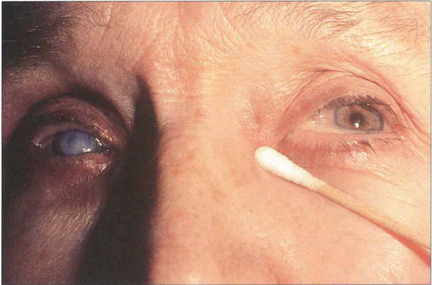

TESTS OF OUTFLOW PATENCY

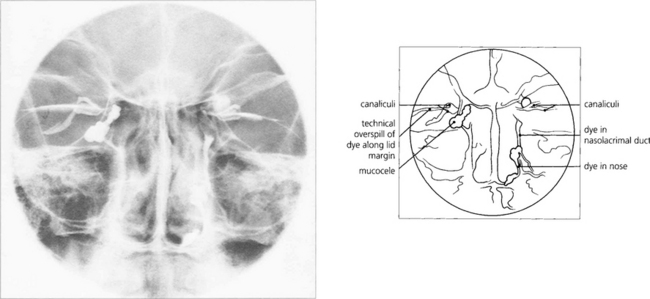

Fig. 20.71 The Jones’ dye test is a refinement of syringing the nasolacrimal system. Its main use is in the evaluation of unrelieved symptoms following dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR). Fluorescein drops are instilled into the conjunctival sac. A cottonwool bud, soaked in local anaesthetic, is placed in the inferior meatus or alongside the rhinostomy site after DCR and examined for signs of fluorescence after 5 min. Identification of nasal dye indicates a physiologically patent, although not necessarily normally functioning, system. Many normal patients have a negative test at this stage and, if so, excess fluorescein is washed from the conjunctiva and the canaliculi are syringed with clear saline. Entry of fluorescein into the nose indicates that dye has entered the sac; if clear saline is seen, fluorescein has not entered the sac and indicates punctal or canalicular stenosis. The absence of saline entering the nose indicates a complete obstruction.

OUTFLOW OBSTRUCTION

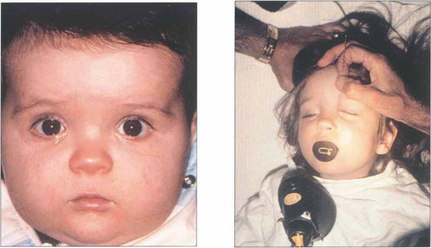

CONGENITAL BLOCKAGE OF THE NASOLACRIMAL DUCT

Fig. 20.73 At birth the process is usually complete but a membrane may persist at the lower end and fail to perforate leaving the child with a watering eye. This can be ruptured with a probe under general anaesthesia if it has not perforated spontaneously by 1 year of age.

Fig. 20.74 This child has a congenital lacrimal fistula with an aberrant punctum lying over the lacrimal sac.

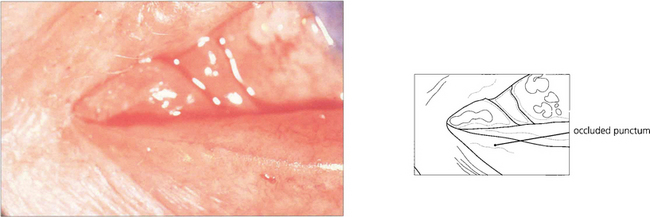

Fig. 20.75 Punctal stenosis follows conjunctival scarring from such inflammatory causes as trachoma, chronic staphylococcal lid disease, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, ocular pemphigoid and topical drugs. Provided the canaliculus is not involved, dilating and opening the punctum with a ‘two or three snip’ operation cures the condition.

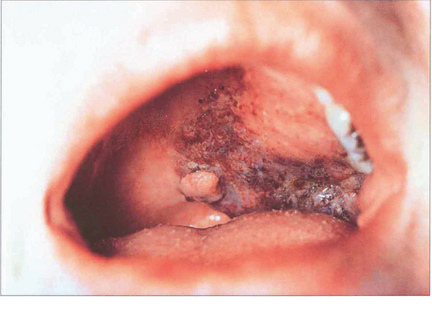

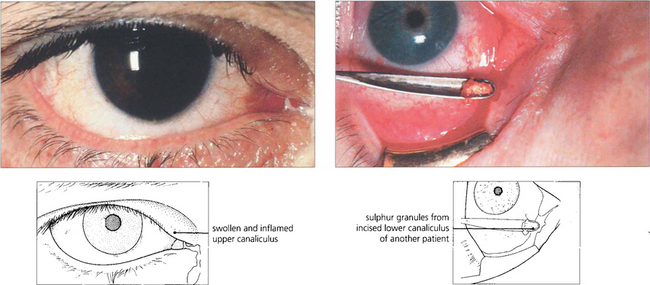

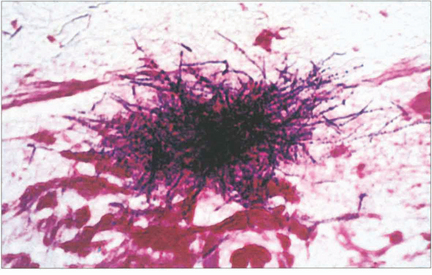

Fig. 20.76 Canaliculitis occurs most commonly from Actinomyces israelii infection. The infected canaliculus becomes chronically red, swollen and tender. Pressure over the swelling sometimes reveals stringy, tenacious mucous and ‘sulphur granules’ at the punctum. Treatment is by incision and curettage of the canaliculus and a short course of topical penicillin.

Fig. 20.77 Typical clusters of Gram-positive Actinomyces can be seen in the ‘sulphur granule’ curettings of this patient.

Fig. 20.78 Obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct as a result of chronic infection or irritation may lead to stasis and an acute infection of the lacrimal sac. Patients present with epiphora and an acutely painful, swollen mass over the area of the lacrimal sac; this may form an abscess and require incision, drainage and systemic antibiotics. Incision, when required, should be performed as far laterally as possible, to facilitate subsequent DCR. DCR is usually necessary to reconstitute lacrimal drainage as soon as the acute inflammation has subsided.

Fig. 20.79 Chronic obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct can lead to a watering eye and a mucocele of the lacrimal sac. Provided the canaliculi are patent, pressure over the sac causes mucoid material to regurgitate through the puncta.

Fig. 20.80 A painless, irreducible mass that extends above the medial canthal tendon may signify a lacrimal sac tumour. There may be associated blood-stained tears or bloody reflux with syringing. Ultrasound will show whether the lesion is solid or cystic and further evaluation with CT or MRI is necessary to plan surgery.