Chapter 9

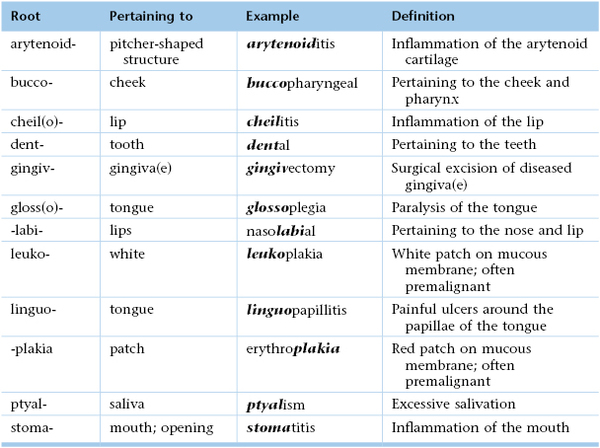

The Oral Cavity and Pharynx

Look to thy mouth; diseases enter here.

George Herbert (1593–1632)

General Considerations

The mouth and oral cavity are used by individuals to express an entire range of emotions. As early as infancy, the mouth provides gratification and sensory pleasure.

Approximately 20% of all visits to primary care physicians are related to problems of the oral cavity and throat. Most patients with these problems present with throat pain, which may be acute and associated with fever or difficulty in swallowing. A sore throat may be the result of local disease, or it may be an early manifestation of a systemic problem.

It has been estimated that more than 90% of patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have at least one oral manifestation of the disease. It appears that as further immunologic impairment develops, the risk of oral lesions increases. There are several important oral manifestations that are strongly associated with early HIV infection. The presence of any of them mandates HIV testing.

Oral cancer is the largest group of those cancers that fall into the head and neck cancer category. It is estimated that in 2013, 42,000 people in the United States will be newly diagnosed with oral cancer. This includes those cancers that occur in the mouth itself, the oropharynx, and on the exterior lip of the mouth. There is a 2 : 1 male-to-female incidence ratio, with oral cancer representing approximately 3% of all new cancer cases in men. This is the fifth year in a row in which there has been an increase in the rate of occurrence of oral cancers; in 2007 there was a major jump of over 11% in that single year. Worldwide, the problem is much greater: more than 600,000 new cases are diagnosed annually.

Although some believe that oral cancer is rare, it will be newly diagnosed in approximately 100 new individuals each day in the United States alone, and a person dies from oral cancer every hour of every day. Cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx was responsible for 7900 deaths in 2011. The rate of death from oral cancer is relatively high because the cancer is routinely discovered late in its development, with metastases to other areas or invasion deep into local structures. Oral cancer is also particularly dangerous because it has a high risk of producing second primary tumors. This means that patients who survive a first encounter with the disease have up to a 20 times higher risk for development of a second cancer. Death rates have, however, been decreasing continuously in both men and women over the past three decades.

For all stages combined, approximately 84% of persons with oral cancer and pharynx cancer survive 1 year after diagnosis. The 5-year and 10-year relative survival rates are 61% and 51%, respectively. There are several pathologic types of oral cancers, but approximately 90% are squamous cell carcinomas. It was estimated in 2010 that approximately $3.2 billion was spent in the United States on the treatment of head and neck cancers.

There are two distinct etiologic factors by which most people develop oral cancer. One is through the use of tobacco and alcohol. The second is human papillomavirus (HPV). Recent studies have shown that incidence is increasing for oral cancers associated with HPV type 16 infection among white men younger than 50 years of age. This is the same virus responsible for the vast majority of cervical cancers in women. A small percentage of people (less than 7%) develop oral cancers from no currently identified cause.

Although the exact cause of tongue cancer remains unknown, it most often occurs in people who use tobacco products (cigarettes, cigars, pipes, and smokeless tobacco), consume alcohol (especially when combined with tobacco use), or chew betel nuts. Chewing of betel nuts, discussed later in this chapter, is not a common practice in the United States, but it is a widespread habit in many parts of the world, especially in Taiwan and India (see Fig. 9-51). HPV infection is associated with cancer of the tonsil, base of the tongue, and other sites of the oropharynx.

In 2012, there were 12,360 new cases of laryngeal cancer in the United States with 3650 deaths attributed to it. There is a clear association between smoking, excess alcohol ingestion, and the development of squamous cell cancers of the larynx. For smokers, the risk of the development of laryngeal cancer decreases after the cessation of smoking but remains elevated even years later when compared with that of nonsmokers. Supraglottic cancers typically present with sore throat, painful swallowing, referred ear pain, change in voice quality, or enlarged neck nodes. Early vocal cord cancers are usually detected because of hoarseness. Prognosis for small laryngeal cancers that have not spread to lymph nodes is very good with cure rates of 75% to 95% depending on the site, tumor bulk, and degree of infiltration.

The clinical picture of the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome has long been recognized without an understanding of the disease process. The term “Pickwickian syndrome” that is sometimes used for the syndrome was coined by the famous early twentieth century physician, Sir William Osler, who must have been a reader of Charles Dickens. The description of Joe, “the fat boy” in Dickens’s novel The Pickwick Papers, is an accurate clinical picture of an adult with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. The early reports of obstructive sleep apnea in the medical literature described individuals who were very severely affected, often presenting with severe hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and congestive heart failure. The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study estimated in 1993 that roughly 1 in every 15 Americans is affected by at least moderate sleep apnea. It also estimated that in middle-age as many as 9% of women and 24% of men are affected, undiagnosed, and untreated. The National Commission on Sleep Disorders Research estimated that minimal sleep apnea affects 7 to 18 million people in the United States and that relatively severe cases affect 1.8 to 4 million people. The prevalence increases with age. Sleep apnea remains undiagnosed in approximately 92% of affected women and 80% of affected men.

The costs of untreated sleep apnea reach further than just health issues. It is estimated that in the United States the average untreated sleep apnea patient’s annual health care costs $1336 more than an individual without sleep apnea. This may cause $3.4 billion per year in additional medical costs.

Many physician visits for oral problems are associated with psychiatric disturbances. Psychosomatic disease symptoms often center on the mouth. Patients with psychosomatic disease may complain of “burning” or “dryness” of the mouth or tongue. Bruxism, or grinding of the teeth other than for chewing, occurs especially during sleep. This overuse of the muscles of mastication has often been interpreted as a manifestation of rage or aggression that is not overtly displayed; it may also be an infantile response to reduce psychic tension. Bruxism can produce facial pain, which causes further spasm of the muscles and continued bruxism, resulting in a vicious circle. Individuals who habitually have something in their mouths, such as a pipe, a thumb, or a pencil, may cause damage to their oral cavities.

Although it is often thought that the oral cavity is examined only by dentists, other health care professionals must have competency in evaluating this important region of the body. The health care provider must be able to accomplish the following:

2. Recognize dental caries and periodontal disease.

4. Recognize oral manifestations of systemic disease.

5. Recognize systemic problems caused by oral disease and procedures.

6. Assess physical findings concerning the range and smoothness of jaw motion.

7. Identify dental appliances.

8. Know when a dental consultation is required or should be postponed because of a medical problem.

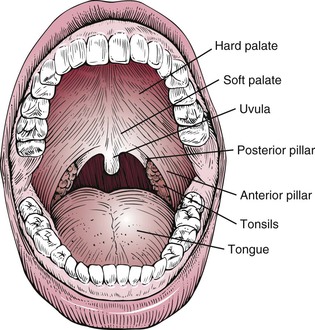

Structure and Physiologic Characteristics

The Oral Cavity

The oral cavity consists of the following structures:

The oral cavity extends from the inner surface of the teeth to the oral pharynx. The hard and soft palates form the roof of the mouth. The soft palate terminates posteriorly at the uvula. The tongue lies at the floor of the mouth. At the most posterior aspect of the oral cavity lie the tonsils, between the anterior and posterior pillars. The oral cavity is illustrated in Figure 9-1.

Figure 9–1 The oral cavity.

The buccal mucosa is a mucous membrane that is continuous with the gingivae and lines the insides of the cheeks. The linea alba, or bite line, is a pale or white line along the line of dental occlusion. It may be slightly raised and show impressions of the teeth.

Lips are red as a result of the increased number of vascular dermal papillae and the thinness of the epidermis in this area. An increase in desaturated hemoglobin, cyanosis, is manifested as blue lips. The common blue discoloration of the lips in a cold environment is related to the decreased blood supply and increased extraction of oxygen.

The tongue lies at the floor of the mouth and is attached to the hyoid bone. It is the main organ of taste, aids in speech, and serves an important function in mastication. The body of the tongue contains intrinsic and extrinsic muscles and contains the strongest muscle of the body. The tongue is supplied by the hypoglossal, or twelfth cranial, nerve.

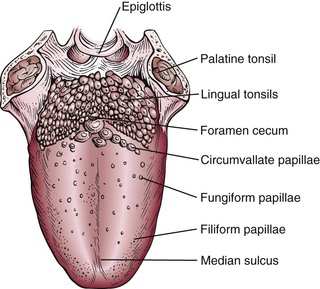

The dorsum of the tongue has a convex surface with a median sulcus. Figure 9-2 shows the tongue viewed from above. At the posterior portion of the sulcus is the foramen cecum, which marks the area of the origin of the thyroid gland. Behind the foramen cecum are mucin-secreting glands and an aggregate of lymphatic tissue called the lingual tonsils. The texture of the tongue is rough as a result of the presence of papillae, the largest of which are the circumvallate papillae (Fig. 9-3). There are approximately 10 of these round papillae, which are located just in front of the foramen cecum and divide the tongue into the anterior two thirds and the posterior one third. Filiform papillae are the most common papillae and are present over the surface of the anterior portion of the tongue. The fungiform papillae are located at the tip and sides of the tongue. These papillae can be recognized from their red color and broad surface.

Figure 9–2 The tongue viewed from above.

Figure 9–3 Circumvallate papillae.

The taste buds are located on the sides of the circumvallate and fungiform papillae. Taste is perceived from the anterior two thirds of the tongue by the chorda tympani nerve, a division of the facial nerve. The glossopharyngeal, or ninth cranial, nerve perceives taste sensation from the posterior third of the tongue. There are four basic taste sensations: sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. Sweetness is detected at the tip of the tongue. Saltiness is sensed at the lateral margins of the tongue. Sourness and bitterness are perceived at the posterior aspect of the tongue and are carried by the glossopharyngeal nerve.

When the tongue is elevated, a mucosal attachment, the frenulum, may be seen underneath the tongue in the midline connecting the tongue to the floor of the mouth.

The hard palate is a concave bone structure. The anterior portion has raised folds, or rugae. Figure 9-4 shows the palatal rugae. The soft palate is a muscular, flexible area posterior to the hard palate. The posterior margin ends at the uvula. The uvula aids in closing off the nasopharynx during swallowing.

Figure 9–4 Palatal rugae.

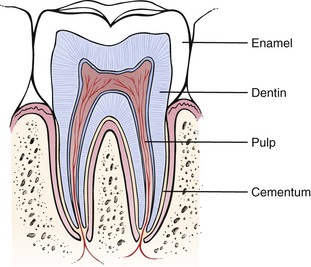

Teeth are composed of several tissues: enamel, dentin, pulp, and cementum. Enamel covers the tooth and is the most highly calcified tissue in the body. The bulk of the tooth is the dentin. Under the dentin is the pulp, which contains branches of the trigeminal, or fifth cranial, nerve and blood vessels. The cementum covers the root of the tooth and attaches it to the bone. Figure 9-5 shows a cross section through a molar tooth.

Figure 9–5 Cross-sectional view through a molar tooth.

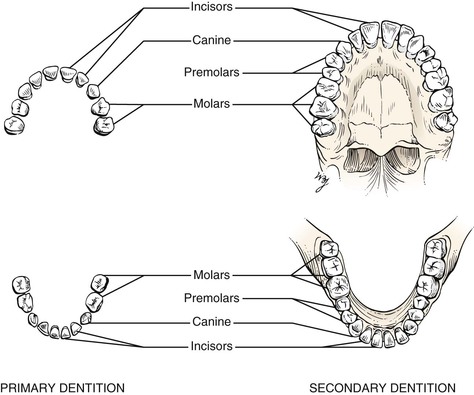

The primary dentition, or the deciduous teeth, consists of 20 teeth that erupt from the ages of 6 to 30 months. The primary dentition per quadrant of jaw consists of two incisors, one canine, and two premolars. These teeth are shed from the ages of 6 to 13 years. The secondary dentition, or the permanent teeth, consists of 32 teeth that erupt from the ages of 6 to 22 years. The secondary dentition per quadrant of jaw consists of two incisors, one canine, two premolars, and three molars. Figure 9-6 illustrates the primary and secondary dentition, and Table 21-4 summarizes the chronology of dentition.

Although not part of the oral cavity proper, the salivary glands are considered part of the mouth. There are three major salivary glands: the parotid, the submandibular, and the sublingual glands. The parotid gland is the largest of the salivary glands. It lies anterior to the ear on the side of the face. The facial, or seventh cranial, nerve courses through the gland. The duct of the parotid gland, Stensen‘s duct, enters the oral cavity through a small papilla opposite the upper first or second molar tooth. The submandibular gland is the second largest salivary gland. It is located below and in front of the angle of the mandible. The duct of the submandibular gland, Wharton‘s duct, terminates in a papilla on either side of the frenulum at the base of the tongue. The sublingual gland is the smallest of the major salivary glands. It is located in the floor of the mouth, beneath the tongue. There are numerous ducts of the sublingual gland, some of which open into Wharton’s duct. In addition to these major salivary glands, there are hundreds of very small salivary glands located throughout the oral cavity.

The Pharynx

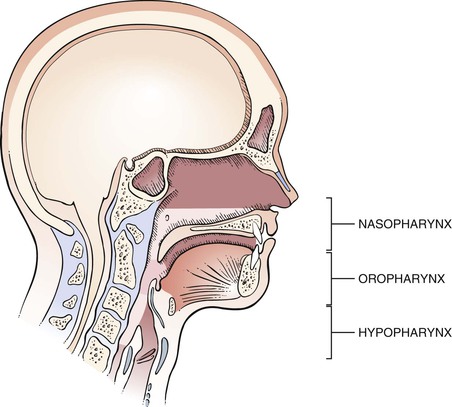

The pharynx is divided into the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the hypopharynx. The nasopharynx lies above the soft palate and is posterior to the nasal cavities. On its posterolateral wall is the opening of the eustachian tube. The adenoids are pharyngeal tonsils and hang from the posterosuperior wall near the opening of the eustachian tube. The oropharynx lies below the soft palate, behind the mouth, and superior to the hyoid bone. Posteriorly, it is bounded by the superior constrictor muscle and the cervical vertebrae. Below the oropharynx is the area known as the hypopharynx (or laryngopharynx). The hypopharynx is surrounded by three constrictor muscles, which are innervated by the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. The hypopharynx ends at the level of the cricoid cartilage, where it communicates with the esophagus through the upper esophageal sphincter. Figure 9-7 illustrates the functional parts of the pharynx.

Figure 9–7 Functional parts of the pharynx.

The muscular walls of the pharynx are formed by the constrictor muscles, which function during the act of swallowing. The blood supply is derived from the external carotid artery.

Lymphatic tissue is abundant in the pharynx. The lymphoid tissue consists of the palatine tonsils, the adenoids, and the lingual tonsils. These tissues form Waldeyer‘s ring. The palatine tonsils lie in the tonsillar fossa, between the anterior and posterior pillars. The palatine tonsils are almond-shaped and vary considerably in size. The adenoids lie on the posterior wall of the nasopharynx, and the lingual tonsils are located at the base of the tongue. The upper portion of the pharynx drains to the retropharyngeal nodes, and the lower part drains to the deep cervical lymph nodes.

The functions of the pharynx are as follows:

Swallowing, or deglutition, is divided into three stages. The voluntary stage occurs when a bolus of food is forced by the tongue past the tonsils to the posterior pharyngeal wall. The second stage is involuntary constriction by the pharyngeal muscles, propelling the bolus from the pharynx to the esophagus. The third stage is also involuntary, in which the esophageal muscles push the bolus down into the stomach. The larynx is first raised and then closed during the first two stages of swallowing. The eustachian tubes open during swallowing when the nasopharynx closes.

The pharynx also acts as a structure of resonation and articulation. Resonation refers to the vibration of a structure. Articulation is the change in shape of a structure to produce speech. Contracting the pharyngeal muscles causes a change in the acoustic quality of speech. Changes in the size and shape of the pharynx affect resonance. The soft palate affects resonance by opening and closing the partition between the oral and nasal cavities. If closure is incomplete, nasal speech results.

The Larynx

The larynx is located at the superior margin of the trachea and below the hyoid bone, which is located at the base of the tongue. The larynx is at the level of the fourth to sixth cervical vertebrae. The larynx functions as a guard against the entrance of solids and liquids into the trachea, as well as being the organ of voice production.

The epiglottis is attached above the larynx. The function of the epiglottis is generally believed to be protection of the airway during swallowing.

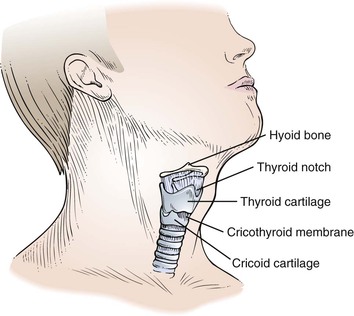

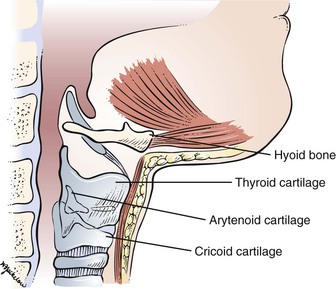

The body of the larynx consists of a series of cartilaginous structures: the thyroid, the cricoid, and the arytenoid cartilages. The thyroid cartilage forms the bulk of the structure of the larynx and produces the prominence in the neck known as the Adam‘s apple. Toward the top of the thyroid cartilage is the thyroid notch. Farther down on the thyroid cartilage, there is a space, the cricothyroid space and membrane, that separates the thyroid cartilage from the cricoid cartilage. The cricoid cartilage articulates with the cricothyroid membrane superiorly and the trachea inferiorly. It is the only complete ring of cartilage in the larynx. The paired arytenoid cartilages provide an important area for attachment of the vocal cords. A diagram of the thyroid and cricoid cartilages onto the neck is illustrated in Figure 9-8, and the laryngeal skeleton is illustrated in Figure 9-9.

Figure 9–8 Laryngeal cartilages.

Figure 9–9 Laryngeal skeleton.

Review of Specific Symptoms

The Oral Cavity

All patients should be asked the following:

“When did you last see a dentist?”

“Have you any pain, sores, or masses on your lips or in your mouth that do not heal?”

“Have you had any problems after extraction of a tooth?”

(If the patient wears dentures) “Have you noticed any change in the way your dentures fit?”

Cancers of the oral cavity are most often found in people who are older than 45 years of age. Cancer of the lip is more common in men than in women and is more likely to develop in people with light-colored skin who have spent extensive time in the sun. Cancer of the oral cavity is more common in people who chew tobacco or smoke pipes. A possible sign of a cancer of the mouth or gums is when dentures no longer fit well.

The most important symptoms of disease of the oral cavity are as follows:

Pain

When a patient complains of oral pain, it is important to ask the following:

“Do you feel the pain anywhere else?”

“How long has the pain been present?”

Tooth pain may be a symptom of underlying gingival disease. A history of dental procedures and recent dental work should be documented.

Pain in the teeth may sometimes be referred from the chest. Patients with angina may actually complain of pain in their teeth associated with exertion. Careful and thoughtful questioning is indicated.

Ulceration

Oral ulcerative lesions are common and may be manifestations of local or systemic disease of immunogenic, infectious, malignant, or traumatic origin. The patient’s history is important because it indicates whether the lesions are acute or chronic, single or multiple, and primary or recurrent.

“Have you had a lesion like this before?”

“How long have the lesions been present?”

“Are there lesions anywhere else on the body, such as in the vagina? In the urethra? In the anus?”

The examiner should ask about a patient’s sexual habits. These questions were discussed in Chapter 1, The Interviewer’s Questions. Smoking and drinking alcohol predispose an individual to precancerous lesions of the mouth, such as leukoplakia and erythroplakia.

Bleeding

Bleeding may result from a primary hematologic disorder or from a local inflammation or neoplasm. Many medications may also cause or predispose a patient to bleeding. Always ask whether the patient is taking any medications.

Mass

If a patient complains of, or on physical examination is found to have, an intraoral mass or a mass in the region of a salivary gland, determine its duration and whether the mass is painful. A painless mass is usually a sign of a tumor.

Are there associated symptoms such as excessive salivation, known as ptyalism, or dryness of the mouth, known as xerostomia? Is dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing) present?

Halitosis

Halitosis affects approximately 50% of all adults. Fortunately, in only a small percentage does the problem persist the entire day. Most individuals with halitosis are told by others that they have bad breath, although they themselves may be unaware of the problem. In some cases, the odor in the mouth is so objectionable that it can compromise the patient’s social and professional life.

The source of bad breath is in the oral cavity in 90% of cases; the other 10% have disorders in the nasal passages or lungs or a systemic disease. It is questionable whether the gastrointestinal tract is a source of halitosis.

It is believed that halitosis is caused by volatile sulfur and other compounds exhaled into the air during speech and respiration. These compounds are produced by putrefactive, gram-negative anaerobic bacteria colonizing on the posterior dorsum of the tongue, in periodontal pockets, and around some dental restorations and prostheses. The volatile sulfur compounds are generated by the bacterial metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids. Xerostomia increases the level of volatile sulfur compounds.

Patients with systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, cirrhosis, uremia, and cancer; infections of the perioral regions; and trimethylaminuria (fish odor syndrome) can suffer from bad breath. These conditions must be considered in the absence of oral and sinonasal disease.

Treatment of halitosis should be directed toward the underlying cause. Once it has been determined that the source of the bad breath is the oral region, the patient should be instructed in procedures of good oral hygiene, including proper tooth brushing, flossing, and, most important, cleaning of the posterior dorsum of the tongue with a special scraping device or toothbrush. Appropriate mouthwash may also be used. These procedures must be performed at least twice a day to remove the bacteria and accumulated metabolic products.

Xerostomia

Xerostomia, or dry mouth, is a common symptom of reduced or absent salivary secretion. It is most common in women and in aging populations. It is frequently observed as a side effect of various medications, including antihistamines, decongestants, tricyclic antidepressants, antihypertensives, and various anticholinergic medications. It may also occur with mouth breathing, neurologic disorders, radiation therapy to the head and neck, HIV infection, and autoimmune disorders. The saliva is thick, and the oral mucosal surfaces are dry; the tongue is commonly fissured and atrophic. The dry environment predisposes to candidiasis and dental caries.

The Pharynx

The most common symptoms of disease of the pharynx include the following:

Nasal Obstruction

Nasal obstruction can result from enlarged adenoids or from tumor formation in the nasopharynx. It is important to determine whether the patient has any allergies or sinus trouble or has sustained nasal trauma.

Pain

Pain can result from inflammation of the tonsils or posterior pharynx, as well as from a tumor in this area. Acute throat pain may be caused by inflammatory processes or injury. A foreign body in the pharynx often produces severe pain that is worsened by swallowing. Often, throat pain may be referred to the ipsilateral ear. Chronic throat pain may be caused by inflammatory processes, as well as by neoplasms. Enlarged thyroid lobes or diffuse thyroid enlargement may cause throat pain associated with dysphagia. Hysteria is another cause of chronic throat pain.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is difficulty in swallowing. Determine the site of obstruction. Does the dysphagia occur with liquids, solids, or tablets? Questions related to tonsillar infections are relevant because enlarged tonsils may interfere with swallowing. It is prudent to ask whether regurgitation of food occurs; this results from an abnormal pharyngeal pouch. The patient may say that the “food gets stuck.” This is often associated with significant disease.

Deafness

A tumor at the distal end of the eustachian tube in the nasopharynx can produce conductive deafness. Benign masses such as hypertrophied adenoids may be responsible. Nasopharyngeal malignancies may also be the cause of conductive deafness. In many cases, serous effusions in the middle ear space cause eustachian tube dysfunction.

Snoring

Snoring is a common complaint. An important problem often associated with heavy snoring is obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep apnea is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition suffered by more than 20 million Americans. Sleep apnea is largely undiagnosed, with only 10% of people with the condition being treated. Sleep apnea is a sleep disorder characterized by brief interruptions of breathing during sleep. During an episode of obstructive apnea, efforts to inhale air create suction that collapses the windpipe. This blocks the airflow for 10 seconds to as much as a minute while the sleeping person attempts to breathe. When the blood oxygen level falls, the brain responds by waking the person enough to tighten the upper airway muscles and open the windpipe. The person may snort or gasp, then resume snoring as he or she falls back to sleep. This cycle may be repeated hundreds of times a night. The frequent awakenings that sleep apnea patients experience leave them continually sleepy and may lead to personality changes such as irritability or depression.

The true prevalence is unknown, but it has been estimated that it is 4% among men and 2% among women from the ages of 30 to 60 years. The prevalence is higher in individuals older than 60 years. Ask the following questions:

“Have you been told that you snore?”

“Does your snoring bother other people?”

“Have breathing pauses been noticed?”

“Are you tired after sleeping?”

“Are you tired during the daytime?”

“Have you ever fallen asleep while driving?”

“Do you have high blood pressure?”

“Is your body mass index greater than 28?”

“Are you 50 years old or older?”

“During usual sleep, have you noticed or been told that you toss and turn frequently?”

“Have you noticed or been told that you kick or jerk your legs repeatedly?”

▪ Sitting and talking to someone

▪ At work

▪ While a passenger in a vehicle

“About how many times per night do you wake up?”

Sleep apnea also deprives the person of oxygen, which can lead to morning headaches or a decline in mental functioning. It also is linked to high blood pressure, irregular heartbeats, and an increased risk of heart attacks and stroke. Patients with severe, untreated sleep apnea are two to three times more likely to have automobile accidents than the general population. In some high-risk individuals, sleep apnea may even lead to sudden death from respiratory arrest during sleep, heart attacks, or strokes.

The presence of snoring, sleepiness, and tiredness are suggestive symptoms of sleep apnea.

To diagnose sleep apnea, doctors may order a sleep study such as a polysomnogram (PSG). For a PSG, the patient will stay usually overnight at a sleep center. This study records brain activity, eye movements, heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, nasal air movement, snoring, and chest movements. The chest movements show whether the patient is making an effort to breathe. If the PSG shows that the patient has sleep apnea, a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine may be recommended. CPAP is a treatment that uses mild air pressure to keep the airways open.

Refer to Chapter 10, The Chest, for more information on sleep apnea.

The Larynx

Dysphonia

The major symptom of laryngeal disease is a change in the voice, especially the development of dysphonia, or hoarseness. Ask the following questions:

“How long have you had the hoarseness?”

“What seems to make it better? Worse?”

“Is there any time of day when it is worse?”

“Have you had any surgery necessitating general anesthesia?”

Determine whether the patient is or was a smoker. Recent onset of hoarseness may result from impingement on the recurrent laryngeal nerve as it hooks around the left bronchus. This may be caused by a tumor or by an enlarged left atrium. Voice overuse or vocal cord neoplasms are other causes of hoarseness. Procedures involving general anesthesia necessitate the use of an endotracheal tube, which could potentially damage a vocal cord and cause hoarseness.

Effect of a Voice Disorder on the Patient

Phonation is the process of sound production by the interaction of airflow through the glottis and the opening and closing of the vocal cords of the larynx. Voice loudness is proportional to the air pressure below the glottis; pitch is related to this pressure and to the length of the vocal cords. Voice quality may change when there is interference with the vocal cords or pharyngeal cavity vibration (i.e., resonance).

A voice disorder may be related to an enlarged vocal cord, a laryngeal mass, or a neurologic or psychologic problem. A voice disorder is defined as the presence of a voice that is different in pitch, quality, loudness, or flexibility in comparison with the voices of other persons of similar age, sex, and ethnic group. An abnormal voice may be a symptom or sign of illness, and its cause should be determined.

In a study of a school-aged population, voice disorders were found in up to 23% of children. Most of these disorders were related to voice abuse and not to organic problems. In another study, 7% of men and 5% of women from 18 to 82 years of age were found to have voice disorders. Most of these disorders were related to organic problems.

Many patients with organic speech disorders are rejected by other people. Their speech may be high-pitched or nasal and a cause of embarrassment. Their self-esteem is low. They are rejected by others because their voice patterns are objectionable.

Just as a voice disorder has an effect on a person, a person can use his or her voice to influence others. The manner in which a person speaks—the quality, pitch, loudness, stress patterns, rate—reflects his or her personality. Psychogenic voice disorders are functional disorders that are manifestations of psychologic imbalance. Voice is a useful indicator of affective disorders, such as depression, manic states, and mood swings, as well as of schizophrenia.

Physical Examination

The equipment necessary for the examination of the oral cavity consists of a penlight, gauze pads, gloves, applicator sticks, and tongue depressors.

The Oral Cavity

The physical examination of the oral cavity includes inspection and palpation of the following structures:

Sit or stand directly in front of the patient, who should be seated. The patient’s face should be well illuminated. Work systematically from front to back so that no areas are omitted. Put on a pair of gloves when palpating any structure in the mouth. When any lesion is found, note its consistency and tenderness. If the patient is wearing dentures, ask him or her to remove them. Inspect the face and mouth for asymmetries and abnormalities.

Evaluate the patient’s breath. Is there any distinctive odor to the patient’s breath? This may suggest poor oral hygiene or systemic disease. A fetid odor may be caused by extensive caries or periodontal disease.

Have the patient open his or her mouth. If the mouth can be opened much beyond 35 mm, subluxation of the jaw may be present. Deviation of the jaw is suggestive of a neuromuscular or temporomandibular joint problem.

Inspect the Lips

Inspect the lips for localized or generalized swellings, and assess the patient’s ability to open the mouth.

Assess the color of the lips. Is cyanosis present? Are there any lesions on the lips? If a lesion is detected, palpate it to characterize its texture and consistency. Figure 9-10 depicts the mouth of a patient with multiple herpetic ulcers, commonly known as cold sores, or herpes simplex labialis, on the lips and external nares. Figure 9-11 depicts multiple telangiectatic lesions on the tongue that are secondary to Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome. In this syndrome, multiple telangiectases are present throughout the gastrointestinal tract. These may bleed insidiously, causing anemia. Figure 9-12 depicts the classic brown pigmentary changes on the lips of a patient with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. This is an autosomal dominant disorder that is characterized by generalized gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis and mucocutaneous pigmentation.

Figure 9–10 Herpes simplex labialis.

A mucocele of the lip is a common bluish, cystic-appearing, painless, translucent, traumatically induced lesion. Mucoceles, which occur mostly on the lower lip, range in size from several millimeters to several centimeters and arise from obstruction or rupture of the minor salivary gland. When ruptured, a mucocele releases a clear, thick fluid. Figure 9-13 depicts a mucocele of the lower lip.

Figure 9–13 Mucocele of the lower lip.

Inspect the Buccal Mucosa

The patient should be asked to open the mouth widely. The mouth should be illuminated with a light source. The buccal mucosa must be evaluated for any lesions or color changes, and the buccal cavity is inspected for any evidence of asymmetry or areas of injection (dilated vessels, usually indicative of inflammation). The buccal mucosa, teeth, and gingivae are easily evaluated by using a tongue depressor to retract the cheek away from the gums, as shown in Figure 9-14. The examiner should inspect for discolorations, evidence of trauma, and the condition of the parotid duct orifice.

Figure 9–14 Inspection of the mouth.

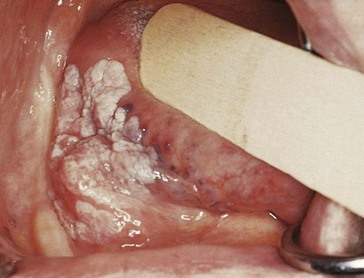

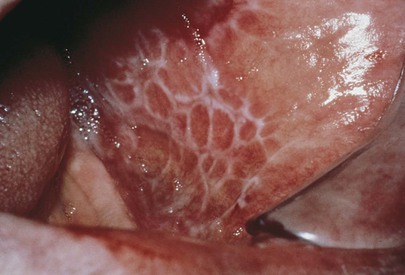

Are there any ulcerations of the buccal mucosa? Are there white lesions on the buccal mucosa? A common painless white lesion in the mouth is lichen planus, which appears as a reticulated, or lacelike, eruption bilaterally on the buccal mucosa. An erosive, painful variant is similar in appearance except for the presence of hemorrhagic and ulcerated lesions. Nonerosive lichen planus is shown in Figure 9-15. Is leukoplakia present? In the mouth, leukoplakia can manifest as a painless, precancerous white plaque on the cheeks, gingivae, and tongue. Leukoplakia of the gingiva is pictured in Figure 9-16. Over 15 years, this lesion developed into verrucous hyperplasia, verrucous carcinoma, and finally squamous cell carcinoma. A resection of the maxilla and palate was required. Figure 9-17 depicts leukoplakia of the tongue in another patient. The thick, white, adherent patches are sharply demarcated and cannot be denuded from the tongue.

Figure 9–15 Nonerosive lichen planus of the buccal mucosa.

Figure 9–16 Leukoplakia of the gingiva.

Figure 9–17 Leukoplakia of the tongue.

Small, pinhead-sized, yellow papules on the buccal mucous membrane are usually Fordyce‘s spots or granules. Fordyce’s spots are normal, prominent, ectopic sebaceous glands commonly seen on the lips or buccal mucosa near the exit of the parotid duct and are probably the most common lesions in the mouth. Figure 9-18 depicts Fordyce’s spots on the buccal mucosa. Ectopic sebaceous glands can also be found on the shaft of the penis (see Fig. 15-11) and on the labia (see Fig. 16-13).

Figure 9–18 Fordyce’s spots (granules) on the buccal mucosa.

Figure 9-19 shows angiokeratomas of the buccal mucosa, or angiokeratoma corporis diffusum, in a patient with Fabry‘s disease. Figure 15-18 depicts angiokeratomas on the scrotum of the same patient.

Figure 9–19 Angiokeratomas of the buccal mucosa.

Inspect the Gingivae

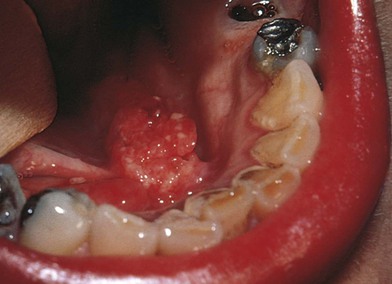

Normal gingivae are stippled, pink, and firm. Does the gingival tissue completely occupy the interdental space? Are the roots of the teeth visible, indicating recession of the periodontal tissue? Is there pus or blood along the gingival margin? Are the gingivae swollen? Is there evidence of bleeding? Is gingival inflammation present? Is abnormal coloration present? Erythroplakia is an area of mucous membrane on which there are granular, erythematous papules that bleed. Erythroplakia has a greater potential for malignancy than does leukoplakia. Figure 9-20 shows the mouth of a patient with erythroplakia of the gingiva (on the right) and inflammatory gingivitis (on the left).

Figure 9–20 Erythroplakia of the gingiva (right).

There are many causes of gingival hyperplasia, including heredity, hormonal imbalances of puberty and pregnancy, medications, and leukemia. Gingival hyperplasia is common in patients taking phenytoin (Dilantin), an antiepilepsy medication, and in those taking nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker. It has been estimated that gingival hyperplasia develops in 30% to 50% of all patients taking phenytoin. The hyperplastic gingival changes of hormonal imbalances usually recede once the hormones have returned to their normal, lower levels. Figure 9-21 depicts marked gingival hyperplasia in a patient who was taking phenytoin. Dense leukemic infiltration of the gingiva is commonly seen in acute monocytic and acute monomyelocytic leukemia. Figure 9-22 shows gingival enlargement and bleeding caused by acute monomyelocytic leukemic infiltration.

Inspect the Teeth

There are 32 teeth in the full adult dentition. Is the dentition appropriate for the patient’s age? The teeth should be inspected for caries and malocclusion. Are the teeth clean, especially around the gum line? Is there discoloration of the teeth? Is there tooth loss? Inspection of the teeth often provides insight into the patient’s attitude toward general hygiene.

Are the teeth aligned properly? Ask the patient to bite normally while you retract the buccal mucosa with a tongue depressor. How many teeth bear force on mastication? Repeat this inspection on the other side. Do the maxillary teeth overlap the mandibular ones, and are they in contact with them? If so, the bite is probably normal.

If the patient is wearing dental appliances such as dentures or bridges, he or she should remove them for a complete evaluation.

Inspect the Tongue

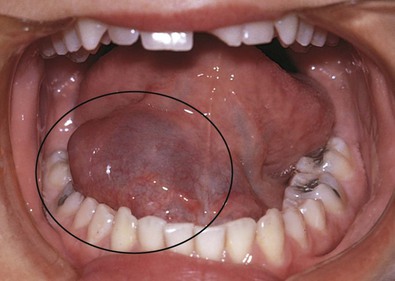

Inspect the mucosa, and note any masses or ulceration. Is the tongue moist? Ask the patient to stick out the tongue. A neuromuscular weakness may be present if the tongue cannot protrude in the midline or move rapidly in all directions. Are there any mass lesions on the sides or undersurface of the tongue? Ask the patient to lift the tongue to the roof of the mouth so that the inferior aspect of the tongue can be inspected. In older individuals, the large veins on the ventral aspect of the tongue may be tortuous. These varicosities never bleed spontaneously and have no clinical significance. Figure 9-23 shows a patient with sublingual varices. Figure 9-24 shows a patient with a benign lipoma of the tongue.

Figure 9–23 Sublingual varices of the tongue.

Figure 9–24 Benign lipoma of the tongue.

A geographic tongue is a benign condition in which the dorsum of the tongue has smooth, localized red areas, denuded of filiform papillae, surrounded by well-defined, raised yellowish-white margins and normal filiform papillae. These areas together give the tongue a maplike appearance. The appearance of the tongue gradually changes as the depapillated areas heal and new areas of depapillation occur. A black hairy tongue is another benign condition in which the filiform papillae on the dorsum of the tongue are greatly elongated; these enlarged, “hairy” papillae become pigmented with a brownish black color caused by staining from food or tobacco or proliferating chromogenic microorganisms. This condition, more commonly seen in men, may be a sequela to antibiotic therapy. A scrotal, or fissured, tongue is another normal variant; approximately 5% of the population has fissures in the tongue. The fissures first develop in late childhood and become deeper with age. The fissure pattern is quite variable. Food debris may collect in the fissures, causing inflammation, but the condition is otherwise benign. Halitosis may be a problem. Figure 9-25 shows these three normal tongue variants.

Figure 9–25 Three normal tongue variants. A, Geographic tongue. B, Black hairy tongue. C, Scrotal, or fissured, tongue.

Is candidiasis present? Candidiasis, also known as moniliasis or thrush, is an opportunistic mycotic infection. It frequently involves the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, perineum, or vagina. The lesions appear as white, loosely adherent membranes, beneath which the mucosa is fiery red. Oral candidiasis is the most common cause of white lesions in the mouth. It is uncommon in healthy individuals who have not been receiving broad-spectrum antibiotic or steroid-based therapies. The presence of thrush in such a patient may be an initial manifestation of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Candidiasis is the most common oral infection in patients with AIDS. The tongue of a patient with AIDS and oral candidiasis is pictured in Figure 9-26.

Figure 9–26 Oral candidiasis.

Is leukoplakia present? One form of leukoplakia, termed oral hairy leukoplakia, is associated with the subsequent development of AIDS. These raised white lesions appear corrugated, or “hairy,” and range in size from a few millimeters to 2 to 3 cm. They are most commonly found on the lateral margins of the tongue but may also be seen on the buccal mucosa. In the absence of other causes of immunosuppression, oral hairy leukoplakia is diagnostic of HIV infection. It is seen in more than 40% of patients with HIV infection. The tongue of a patient with AIDS with oral hairy leukoplakia is pictured in Figure 9-27.

Figure 9–27 Oral hairy leukoplakia.

Look for indurated ulcers or masses in the middle, lateral aspect of the tongue. This is the most common site for intraoral squamous cell carcinoma. Figure 9-28 depicts squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in the classic location.

Figure 9–28 Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue.

Palpate the Tongue

After a thorough inspection of the tongue, the examination proceeds with palpation. The patient sticks out the tongue onto a piece of gauze. The tongue is then held by the examiner’s right hand as the sides of the tongue are inspected and palpated with the left hand. This is illustrated in Figure 9-29. To examine the other side of the tongue, the examiner reverses hands.

Figure 9–29 Palpation of the tongue.

The anterior two thirds and the lateral margins of the tongue can be evaluated without stimulating the gag reflex. The examiner should palpate the lateral margins of the tongue because more than 85% of all lingual cancers arise in this area. All white lesions should be palpated. Is there evidence of induration (hardness)? Induration or ulceration is strongly suggestive of carcinoma. After the tongue is palpated, it is unwrapped, and the gauze is discarded. Any intraoral lesion, ulcer, or mass present for more than 2 weeks should be examined through biopsy and evaluated by an oral pathologist.

Inspect the Floor of the Mouth

The patient is asked to lift the tongue to the roof of the mouth, and the examiner inspects the floor of the mouth. Is there edema on the floor of the mouth? The opening of the submandibular gland, Wharton’s duct, should be observed. The examiner should look for leukoplakia, erythroplakia, or a mass.

A ranula is a large mucous retention cyst on the floor of the mouth in association with submandibular and sublingual glands. The lesion is unilateral, painless, and bluish. It is lateral to the frenulum and is typically larger than a mucocele. As a ranula increases in size, there may be a reduction in tongue movement and difficulty in speech and swallowing. An example of a ranula is pictured in Figure 9-30.

Figure 9–30 Ranula.

Palpate the Floor of the Mouth

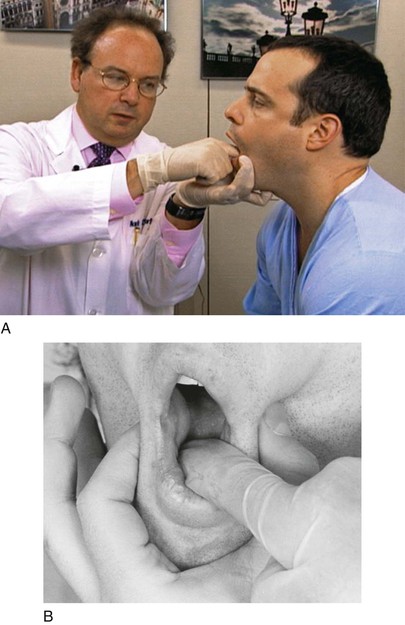

The floor of the mouth should be examined by bimanual palpation. This is performed by placing one finger under the tongue and another finger under the chin to assess any thickening or masses. Whenever palpating in a patient’s mouth, the examiner should hold the patient’s cheeks, as shown in Figure 9-31. This is done as a precaution in case the patient suddenly tries to speak or bite down on the examiner’s finger. The examiner’s right index finger is placed under the tongue; the left thumb and third finger are pushing the patient’s cheeks inward to prevent biting; and the left index finger palpates under the patient’s chin.

Inspect the Hard and Soft Palates

Inspect the rugae and vault shape of the palates. Also inspect the palates for ulceration and masses. Masses are usually minor salivary gland tumors, mostly malignant. Are any white plaques present? Is the soft palate edematous? Is the uvula in the midline?

Is the palate intact? Figure 9-32 shows a severe cleft palate. Clefts of the palate and lips are distinct entities but are closely related embryologically, functionally, and genetically. The incidence of an isolated cleft palate is 1 per 1000 births. Clefts of the palate vary widely in size and shape. They can extend from the soft palate, to the hard palate, and to the incisive foramen. Recurrent otitis media, hearing loss, and speech defects are frequent complications.

Figure 9–32 Cleft palate.

In patients with impaired immunity, or in those whose microbial flora has been altered by antibiotics, Candida albicans, a normal commensal organism of the gastrointestinal tract, can become highly invasive, as seen in Figure 9-33. The patient, who has AIDS, has pseudomembranous candidiasis of the palate and uvula.

Figure 9–33 Pseudomembranous candidiasis.

Are petechiae present? Petechiae are commonly seen in association with infective endocarditis, leukemia, oral sex, and viral infections such as infectious mononucleosis. Fellatio can result in palatal petechiae, characteristically at the junction of the hard and soft palates, as pictured in Figure 9-34.

Figure 9–34 Palatal petechiae.

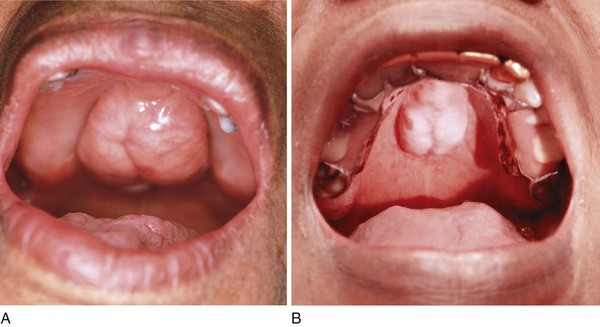

A common finding is a torus palatinus, which is a discrete, hard, lobulated swelling in the midline of the posterior portion of the hard palate. This benign lesion is an overgrowth of the palatine bone. It is painless and asymptomatic and occurs twice as often in women as in men. It may remain undetected until it interferes with the fit of a denture. More than 20% of the population have at least a small torus palatinus. Figure 9-35 shows tori palatini in two patients. Not uncommonly, individuals may have multiple tori palatini; Figure 9-36 shows a patient with three tori palatini. A torus mandibularis is a hard, bony, often bilateral swelling that protrudes from the lingual surface of the mandible at the level of the premolar teeth. It is much less common than a torus palatinus. Approximately 5% to 10% of the population have a torus mandibularis; however, one fifth of mandibular tori are unilateral. Figure 9-37 shows bilateral mandibular tori in two patients.

Figure 9–35 A and B, Torus palatinus.

Figure 9–36 Multiple tori palatini.

Figure 9–37 A and B, Bilateral mandibular tori.

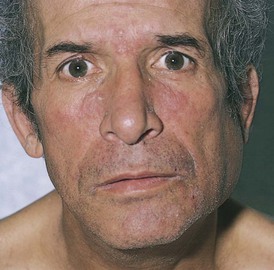

Figure 9-38 shows a patient with early invasive erythroplakia (red plaque) of the palate.

Figure 9–38 Erythroplakia of the palate.

Inspect the Salivary Glands

The ductal orifices of the parotid gland and the submandibular gland should be visualized. The condition of the papillae should be inspected. Is there a flow of saliva? This is best evaluated by drying the papilla with a cotton applicator and observing the flow of saliva produced by exerting external pressure on the gland itself.

The salivary glands are usually not visible. Careful observation of the face determines any asymmetry that is due to unilateral salivary gland enlargement. Obstruction to flow or infiltration of the gland results in glandular enlargement. Figure 9-39 illustrates a patient with left parotid enlargement as a result of obstruction to flow by a stone.

Figure 9–39 Left parotid enlargement.

Palpate the parotid and submandibular glands. Determine the consistency of each gland. Is tenderness present?

Inspect the Twelfth Cranial Nerve

Ask the patient to stick out the tongue. Does the tongue deviate to one side? A hypoglossal, or twelfth cranial, nerve palsy does not allow the lingual muscles on the affected side to contract normally. Consequently, the contralateral side “pushes” the tongue to the side of the lesion.

The Pharynx

Inspect the Pharynx

Examination of the pharynx is limited to inspection. To visualize the palate and oropharynx adequately, the examiner usually must use a tongue depressor. The patient is asked to open the mouth widely, stick out the tongue, and breathe slowly through the mouth. On occasion, leaving the tongue in the floor of the mouth provides better visibility. The examiner should hold the tongue depressor in the right hand and a light source in the left. The tongue blade should be placed on the middle third of the tongue. The tongue is depressed and scooped forward behind the front teeth. The examiner should be careful not to press the patient’s lower lip or tongue against the teeth with the tongue depressor. If the tongue depressor is placed too anteriorly, the posterior portion of the tongue will mound up, making inspection of the pharynx difficult; if placed too posteriorly, the gag reflex may be stimulated.

Is infection present? Is candidiasis present?

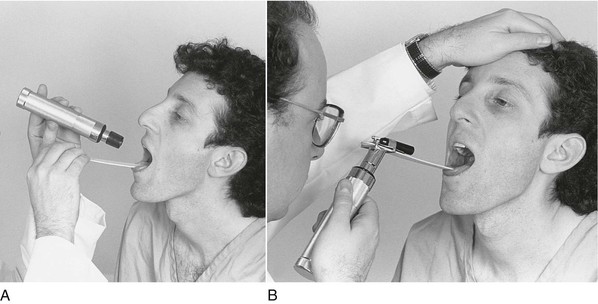

An accessory for the oto-ophthalmoscope handle is a light source that holds the tongue depressor and makes the examination easier. Both techniques of holding the tongue depressor are demonstrated in Figure 9-40.

Inspect the Tonsils

Evaluate tonsillar size. Tonsillar enlargement results from infection or tumor. In chronic tonsillar infection, the deep tonsillar crypts may contain cheeselike debris. Figure 9-41 shows enormous tonsillar enlargement, known as “kissing tonsils.” Figure 9-42 depicts massive tonsillar enlargement in a patient with infectious mononucleosis; the cheeselike deposit in the tonsillar crypts is visible.

Figure 9–41 “Kissing tonsils.” Notice the tonsillar crypts.

Figure 9–42 Infectious mononucleosis. Note the massive tonsillar enlargement and the cheeselike substance in the crypts.

Is a pseudomembranous patch or membrane present over the tonsils? A membrane is associated with acute tonsillitis, infectious mononucleosis, and diphtheria. Figure 9-43 shows the oral cavity, characterized by erythema and a gray, membranous exudate, in a patient with diphtheria.

Figure 9–43 Pseudomembrane secondary to diphtheria.

Inspect the Posterior Pharyngeal Wall

Is there a discharge, mass, ulceration, or infection present? Ask the patient to say, “Aahhh,” as you observe for soft palate elevation.

Inspect the Gag Reflex

At the end of the inspection, tell the patient that you are now going to test the gag reflex. The tip of the tongue depressor should gently touch the posterior surface of the tongue or the posterior pharyngeal wall. The gag reflex should follow rapidly.

The Larynx

Using the Laryngeal Mirror

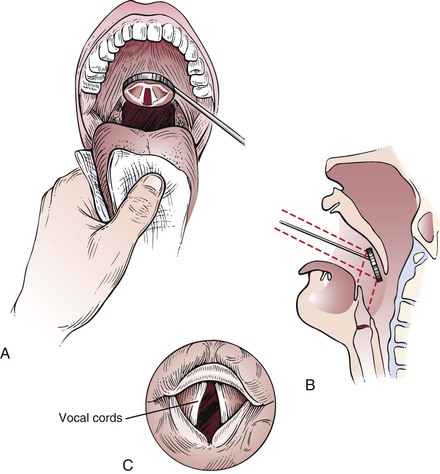

The tongue is held while a small, slightly warmed mirror is introduced into the mouth. The mirror should not be excessively warm and should avoid contact with the tongue. The patient is asked to breathe normally through the mouth. The mirror should be pushed upward against the uvula and positioned in the oropharynx. A beam of light can then be reflected off the mirror onto the internal laryngeal structures. This technique is demonstrated in Figure 9-44.

Figure 9–44 Mirror laryngoscopy. A, Proper technique for holding the tongue and placement of the mirror. B, Cross-sectional view through the pharynx, illustrating placement of the mirror. C, Mirror reflection of the vocal cords.

Although the examination of the larynx is important, indirect laryngoscopy is usually performed only by specialists. Any patient exhibiting symptoms of laryngeal disease should certainly be evaluated further.

Clinicopathologic Correlations

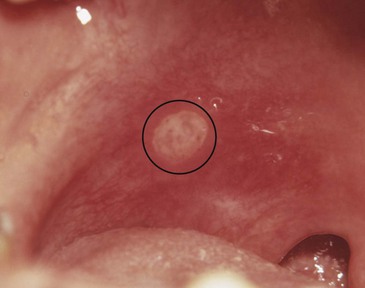

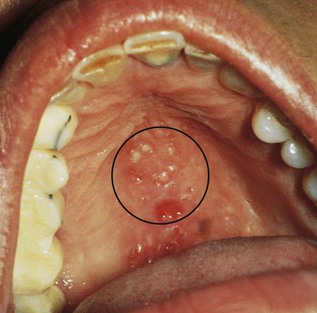

Lesions of the oral cavity are common. The most common acute oral ulcer is the traumatic ulcer; the aphthous ulcer, or canker sore, is the next most common. Traumatic and aphthous lesions vary widely in size, although the latter are usually less than 1 cm in diameter. Both are relatively superficial with raised borders. Aphthous ulcers are usually located on the loose buccal or labial mucosa, whereas traumatic ulcers can occur anywhere. Despite the small size of many of these ulcers, they can be extremely painful. In addition, aphthous ulcers may recur in many patients. Both types of ulcers usually heal within 2 to 3 weeks without scarring. A solitary, or giant, aphthous ulcer of the palate is shown in Figure 9-45. The patient has periadenitis mucosa necrotica recurrens, also known as major aphthous ulcer. These lesions are larger than multiple aphthous ulcers and start as submucosal lesions that break down to form ulcers that may persist for many weeks before healing by secondary intention. Any part of the oropharynx may be affected, but the tonsils and soft palate are the most common sites.

Figure 9–45 Solitary aphthous ulcer.

Acute multiple ulcers that are preceded by or associated with vesicles may have infective or immunologic causes. Primary herpes simplex, herpes zoster, coxsackievirus, and HIV are causative infective agents. Allergic stomatitis, benign mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, Behçet’s disease, and erythema multiforme are common immunologic causes. Radiation therapy or chemotherapy may predispose an individual to the development of acute multiple ulcers.

Benign mucous membrane pemphigoid, or cicatricial pemphigoid, is a chronic mucocutaneous bullous disease of older adults in which the lesions are commonly limited to the oral cavity and conjunctiva. Subepidermal bullae, up to 2 cm in size, and autoantibodies to the basement membrane are present; erosion may be present as well. Skin involvement is rare and usually not severe. Nikolsky’s sign, in which the bulla or external layer of mucous membrane or skin is easily separated from the underlying tissue by slight friction, is usually positive. Figure 9-46 depicts benign mucous membrane pemphigoid. Note the denudation of the gingivae. Figure 9-47 depicts cicatricial pemphigoid. The most common oral finding is patchy, desquamative gingivitis, as seen in this figure.

Figure 9–46 Benign mucous membrane pemphigoid.

Figure 9–47 Cicatricial pemphigoid.

Pemphigus vulgaris affects the oral cavity in 75% of cases. Autoantibodies to the epithelial intercellular substance are present. Nikolsky’s sign1 is negative. The lesions are almost always painful. Figure 9-48 depicts pemphigus vulgaris; the desquamative gingivitis is visible. Another case of pemphigus vulgaris is seen in Figure 9-49. Note the large and confluent ulcerations, which were painful, on the soft palate.

Figure 9–48 Pemphigus vulgaris.

Figure 9–49 Pemphigus vulgaris.

Large chronic single ulcers may result from fungal infections such as aspergillosis or histoplasmosis. Infections by herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, Mycobacterium organisms (which cause tuberculosis), and Treponema pallidum (which causes syphilis) are also well-known causes of this type of ulcer. Immunologic disorders such as pemphigus, systemic lupus erythematosus, bullous pemphigoid, and erosive lichen planus are often the cause of chronic multiple ulcers.

Cancer of the oral cavity is common. Carcinoma of the lip accounts for 30% of all cancers in this area and approximately 0.6% of all cancers. Most of these malignant tumors are squamous cell carcinomas. The lower lip is the site most frequently involved (95%). The patients are usually 50 to 70 years of age, with a strong male predominance (95%). Squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by a hard, infiltrative, usually painless ulcer. The risk factors that predispose to squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity are the same as for leukoplakia: smoking, spirits (alcohol), spices, syphilis, and spikes (ill-fitting dentures)—the “five Ss.” Figure 9-50 depicts a squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip.

Figure 9–50 Squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip.

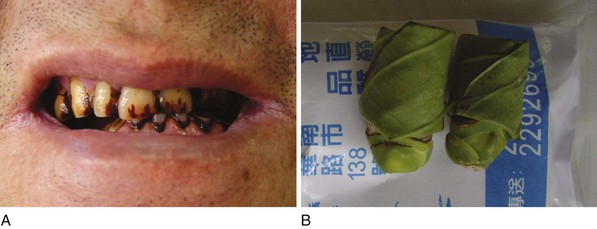

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, risk factors for oral cancers include tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and chewing betel nuts. Betel nuts are actually seeds of the betel palm (Areca catechu). Betel nut and leaf chewing is a tradition that dates back thousands of years. The nuts are chewed for their mildly euphoric stimulant effect, attributed to the presence of relatively high levels of psychoactive alkaloids. Chewing betel nuts increases the capacity to work, creates a warm sensation in the body, heightens alertness, and increases sweating. Although betel nut chewing is a part of many Asian and Pacific cultures and often takes place at ceremonies and gatherings, betel nuts and leaves are often sold at roadside booths decorated with multicolored neon lights for taxi and truck drivers to keep them awake. In India and Pakistan, the preparation of betel nut with or without the betel leaf is commonly referred to as paan.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer regards the betel nut as a known human carcinogen. In Asian countries and communities where betel nuts are consumed extensively, oral cancer accounts for up to 50% of all malignant cancers. Betel nut chewers in Taiwan were found to have a risk of acquiring oral cancer 28 times higher than that of nonusers, and people who chew betel nuts, smoke cigarettes, and drink alcohol are 123 times more likely to develop oral cancer. The Taiwan Department of Health’s statistics of cancer rates in 2008 and the death rate in 2010 showed that oral cancer ranked fourth among the 10 leading causes of cancer mortality among men in Taiwan, and that approximately 6000 people were diagnosed with oral cancer each year. Of people with oral cancer in Taiwan, 9 out of 10 chew betel nuts. In 2006 in Taiwan, it was estimated that the government spent at least NT$5 billion (US$151 million) to cover medical expenses for betel nut–related diseases. Figure 9-51A shows the mouth of a patient from Taiwan with a long-standing habit of betel nut chewing; note the red stain on his teeth. Figure 9-51B shows a betel nut wrapped in its leaf.

In addition to these risk factors, biologic factors include viruses and fungi, which have been found in association with oral cancers. HPV, particularly strains HPV-16 and HPV-18, has been implicated in some oral cancers. HPV is a common sexually transmitted virus that infects approximately 40 million Americans. There are more than 80 strains of HPV, most thought to be harmless. However, 1% of persons infected have the HPV-16 strain, which is a causative agent in cervical cancer and now is linked to oral cancer as well. Another possible risk factor for oral cancer is lichen planus, an inflammatory disease of the oral soft tissues.

Lingual carcinoma is often easily missed because, in its early stages, it is usually painless. In 2007, it was estimated that there were 9800 new cases of lingual cancer. It occurs on the lateral aspects of the tongue or on its undersurface; there is commonly extension onto the tongue from a lesion on the floor of the mouth. Figure 9-52 depicts a carcinoma of the right lateral border of the tongue. Figure 9-53 depicts squamous cell carcinoma of the right lateral border of the tongue in another patient, with extension on the floor of the mouth.

Figure 9–52 Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue.

Carcinoma of the floor of the mouth accounts for 10% to 15% of all oral cancers and is the most common site of oral cancer in African Americans. In 2007, it was estimated that there were 10,660 new cases of floor of the mouth cancer. It occurs primarily in men at an average age of 65 years. Approximately 20% of patients with carcinoma of the floor of the mouth have a second primary tumor. It is particularly important to examine the area behind the last molar tooth and the associated floor of the mouth and base of the tongue. Figure 9-54 shows a squamous cell carcinoma of the floor of the mouth.

Salivary gland neoplasms are not uncommon. They occur with an annual incidence of 6 per 100,000 individuals. More than 70% occur in the parotid gland. There are more than 50 types of salivary gland tumors. The most common salivary gland tumor (65%) is the pleomorphic adenoma, and 20% of these mixed-cell tumors are malignant. Tumors of the submandibular gland are much less frequent, but 40% are malignant. Sublingual gland tumors are rare but usually malignant.

Herpetic gingivostomatitis is infection of the gums and oral mucosa by herpes simplex virus. Small vesicles form on the oral mucous membrane and rapidly break down into painful ulcers on an intensely erythematous base. Figure 9-55 depicts herpetic gingivostomatitis; the multiple erosions and marginal gingivitis are apparent. Figure 9-56 shows herpetic lesions on the palate with ulceration.

Figure 9–55 Herpetic gingivostomatitis.

Figure 9–56 Herpetic lesions on the palate.

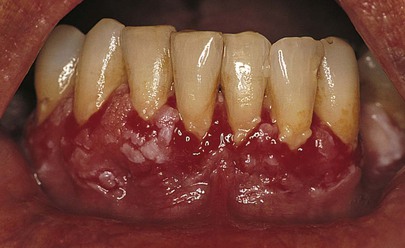

Acute necrotizing gingivostomatitis (also known as ulcerative gingivostomatitis or Vincent‘s gingivitis) is a severe, noncommunicable disease of young adults resulting from infection by Fusobacterium nucleatum or Borrelia vincentii. Most cases occur suddenly in the spring or autumn. The patients, commonly men with poor oral hygiene, present with gingival bleeding, alteration of taste, gingival pain, malaise, fever, and halitosis. As the disease progresses, a whitish pseudomembrane develops along the gingival margins, with ulceration and blunting of the interdental papillae. Acute necrotizing gingivitis, pictured in Figure 9-57, may be an early feature of HIV infection.

Figure 9–57 Acute necrotizing gingivostomatitis.

On August 6, 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a new estimate of the annual number of new HIV infections (HIV incidence) in the United States, revealing that the HIV epidemic is worse than previously thought. That estimate indicated that approximately 56,300 people were newly infected with HIV in the United States in 2006, which is higher than the CDC’s previous estimate of 40,000. The new estimate also confirmed that gay and bisexual men of all races, African Americans, and Hispanics/Latinos were most heavily affected by HIV. Although first observed in men having sex with men, HIV is spreading among the heterosexual population. These cases are related to the use of recreational drugs and contaminated needles, prostitution, and unprotected sex. It has been estimated that more than 90% of patients infected with HIV will have at least one oral manifestation of their disease. It appears that as further immunologic impairment develops, the risk of oral lesions increases. It has also been shown that the oral manifestations can be used as a marker of immune compromise, which is independent of the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count. If left untreated, the oral lesions may interfere with chewing, swallowing, and talking. Many patients have such severe pain that they reduce their oral intake, which results in additional weight loss, malnutrition, and further wasting.

A common oral manifestation of HIV infection is angular cheilitis, also known as perlèche. This painful condition is characterized by macerated, fissured, eroded, encrusted, whitish (occasionally erythematous) lesions in the corners of the mouth. Accumulations of saliva gather in the skin folds and are subsequently colonized by yeast organisms such as C. albicans. Angular cheilitis may be associated with intraoral candidiasis. Angular cheilitis may also develop in patients with normal immunity who wear ill-fitting dentures or wear dentures during the night. An example of angular cheilitis is pictured in Figure 9-58.

Figure 9–58 Angular cheilitis.

Figures 9-26 and 9-33 show patients with oral candidiasis, another extremely common condition associated with HIV infection. Oral candidiasis is characterized by chronic severe pain in the throat that worsens on swallowing or eating. The curdlike white plaques are soft and friable and can easily be wiped off, leaving an area of intensely erythematous mucosa.

Figure 9-27 shows a patient with oral hairy leukoplakia. As mentioned previously, this lesion is seen most frequently either unilaterally or bilaterally on the lateral margins of the tongue. The lesion is white, does not rub off, and occasionally occurs elsewhere in the mouth and oropharynx. Although not correlated with the stage of HIV infection, oral hairy leukoplakia may be the first sign of infection. It is seen most commonly in gay and bisexual men infected with HIV. It has been suggested that the Epstein-Barr virus may be a cofactor in the development of oral hairy leukoplakia. The finding of oral hairy leukoplakia mandates HIV testing.

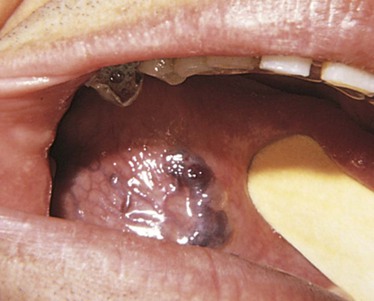

As discussed in Chapter 5, The Skin, the oral lesions of Kaposi’s sarcoma are common. Figure 5-100 shows some of the typical oral lesions. Lesions of Kaposi’s sarcoma of the tongue (Fig. 9-59) and the hard palate (Fig. 9-60) are frequently found in patients with AIDS.

Figure 9–59 Kaposi’s sarcoma of the tongue.

Figure 9–60 Kaposi’s sarcoma of the hard palate.

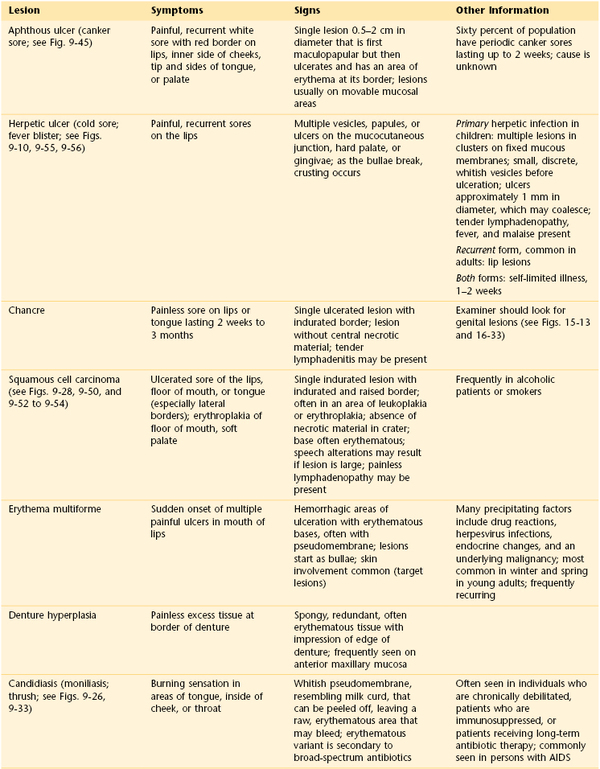

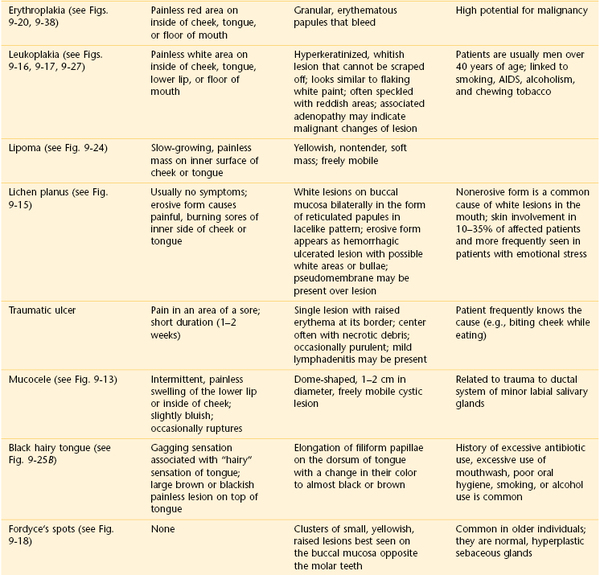

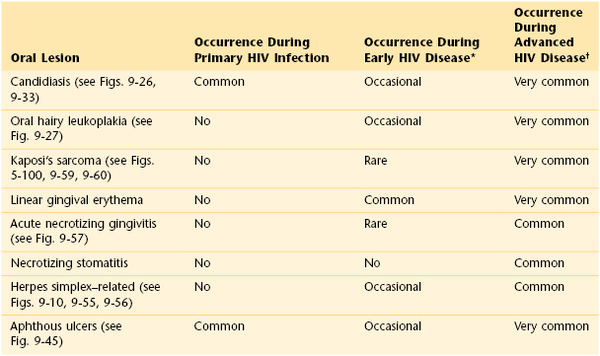

Table 9-1 summarizes the important signs and symptoms of some of the more common oral lesions. Table 9-2 reviews the most common oral lesions seen during the stages of HIV infection. Table 21-4 lists the chronology of dentition.

Table 9–2

Occurrence of Oral Lesions During the Stages of HIV Infection

* CD4+ count > 500 cells/mm3.

† CD4+ count < 200 cells/mm3.

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus.

Adapted from Weinert M, Grimes RM, Lynch DP: Oral manifestations of HIV infection, Ann Intern Med 125:485, 1996.

The bibliography for this chapter is available at studentconsult.com.

Bibliography

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures. American Cancer Society: Atlanta; 2007.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2012. American Cancer Society: Atlanta; 2012 http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-031941.pdf.

Armstrong WB, Vokes DE, Maisel RH. Malignant tumors of the larynx. [ch 107] Flint PW, et al. Cummings otolaryngology head and neck surgery. ed 5. Mosby Elsevier: St Louis; 2010.

Gupta PC, Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of areca nut usage. Addict Biol. 2002;7:77.

Hall HI, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520.

I-Chia L. Most oral cancers caused by betel nuts, bureau says. [Taipei Times, April 19, 2012. Available at] http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2012/04/19/2003530723 [Accessed February 7, 2013] .

Kirby AJ, et al. Thrush and fever as measures of immunocompetence in HIV-1–infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:1242.

McIsaac WJ, et al. Empirical validation of guidelines for the management of pharyngitis in children and adults. JAMA. 2004;291:1587.

Moore PS, Chang Y. Detection of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in Kaposi’s sarcoma in patients with and without HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1181.

National Cancer Institute. General information about laryngeal cancer. [Updated October 23, 2012. Available at] http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/laryngeal/HealthProfessional [Accessed February 5, 2013] .

Neuner JM, et al. Diagnosis and management of adults with pharyngitis: a cost-effective analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2004;139:113.

Oral Cancer Foundation. Oral cancer facts: rates of occurrence in the United States. [Updated October 15, 2012. Available at] http://oralcancerfoundation.org/facts/index.htm [Accessed February 6, 2013] .

Patil SP, et al. Adult obstructive sleep apnea: pathophysiology and diagnosis. Chest. 2007;132:325.

Posner M. Head and neck cancer. [ch 196] Goldman L, Schafer AI. Cecil medicine. ed 24. Saunders Elsevier: Philadelphia; 2011.

Rosenberg M. Clinical assessment of bad breath: current concepts. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:475.

Selim B, Won C, Yaggi HK. Cardiovascular complications of sleep apnea. Clin Chest Med. 2010;31(2):203.

Silverman S. Color atlas of oral manifestations of AIDS. ed 2. Mosby–Year Book: St Louis; 1996.

Speilman AL, Bivona P, Rifkin BR. Halitosis: a common oral problem. N Y State Dent J. 1996;62:36.

Strohl KP. Overview of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview_of_obstructive_sleep_apnea_in_adults [Accessed August 15, 2013] .

Vincent MT, Celestin N, Hussain AN. Pharyngitis. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1465.

Warnakulasuriya S, Trivedy C, Peters TJ. Areca nut use: an independent risk factor for oral cancer. BMJ. 2002;324:799.

What is sleep apnea? National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/sleep_apnea/sleep_apnea.htm [Accessed April 27, 2012] .

Wu MT, et al. Risk of betel chewing for oesophageal cancer in Taiwan. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:658.

Yaggi HK, Strohl KP. Adult obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: definitions, risk factors, and pathogenesis. Clin Chest Med. 2010;179:31.

1 Nikolsky’s sign is a dermatologic finding in which the top layers of the skin slip away from the lower layers when slightly rubbed.