CHAPTER 9 The obsessive-compulsive spectrum

Obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders are characterised by the presence of:

obsessional thoughts, which are recognised by the individual as their own, and are intrusive, anxiety-provoking and distressing, and

obsessional thoughts, which are recognised by the individual as their own, and are intrusive, anxiety-provoking and distressing, and compulsions, which are ritualised acts or mental processes responsive to the obsession and which reduce (at least in the short term) the anxiety associated with the obsession.

compulsions, which are ritualised acts or mental processes responsive to the obsession and which reduce (at least in the short term) the anxiety associated with the obsession.Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

When obsessional thoughts become excessively intrusive, and the obsessions and compulsions become time-consuming (over an hour a day) and interfere with daily functioning, the individual can be considered to have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), as long as other psychiatric and medical (organic) causes have been excluded.

OCD itself can manifest in a number of ways. The most robust subtypes of OCD are shown in Box 9.1. There is overlap between these subtypes, and some patients present with symptoms from a number of them at the same time or at different time-points on their illness trajectory.

There is less debate about gender differences, with most studies suggesting an equal lifetime risk for males and females, but with males having an overall earlier onset of illness (late teens versus early 20s for females). The longitudinal course of illness is variable, and symptoms often wax and wane, usually worsening at times of personal stress.

Management

The management of OCD encompasses psychological and pharmacological domains.

Pharmacological domain

The most effective and well-established pharmacotherapy for OCD is serotonergic antidepressants, including the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and clomipramine (see Ch 13). Doses required are often higher than those usually needed for depression and it can take some months of treatment to see the full benefit. Many patients are left with residual symptoms, and some of these benefit from the adjunctive use of other agents such as antipsychotics. There is some evidence that patients with concomitant motor tics or schizotypal personality disorder benefit particularly from this latter approach.

Obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders

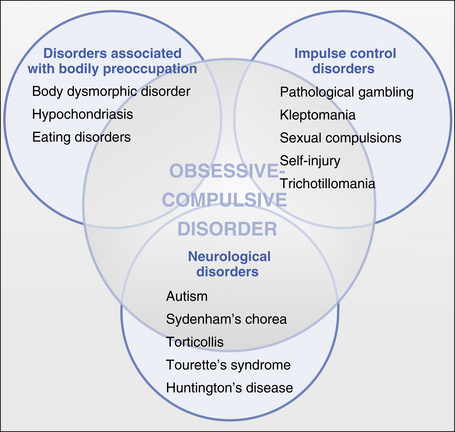

Obsessions and/or compulsions can also occur in a number of other disorders, as shown in Figure 9.1. These are sometimes grouped together into a so-called obsessive-compulsive spectrum of disorders (OCS). While the veracity of this approach is open to criticism, and some members of the spectrum fit much more snugly than do others, we use this overall structure here to address these groups of disorders in turn.

Disorders associated with bodily preoccupation

Hypochondriasis

This is a somewhat old-fashioned term which refers to a preoccupation with physical health, a belief one has a physical illness, and the seeking of help for this perceived problem from health professionals. Numerous medical tests and reassurance from health professionals are to no avail. It is one manifestation of somatisation, and is classed with the somatoform disorders in DSM–IVTR (see Ch 11). Hypochondriacal preoccupations can be seen in a number of other disorders, including depression (where they can reach delusional intensity: see Ch 6), generalised anxiety disorder (see Ch 8), and monosymptomatic hypochondriacal delusions (in DSM–IVTR, delusional disorder, somatic subtype: see Ch 5).

Neurological disorders

A number of other neuropsychiatric disorders can manifest OCS. These include autism, Huntington’s disease and Tourette’s syndrome.

Impulse control (‘habit’) disorders

CASE EXAMPLES: obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders

Obsessive-compulsive syndrome secondary to an atypical antipsychotic

A 40-year-old man with schizophrenia developed, after commencing the antipsychotic clozapine, ritualised checking and cleaning behaviours, which themselves became distressing and very time-consuming. The beliefs were quite independent of any psychotic beliefs, which had actually abated with the clozapine. Treatment was to continue the clozapine and treat the OCS with the established psychological and pharmacological techniques (note that the antidepressant fluvoxamine should be avoided as it interacts with clozapine).

References and further reading

Castle D., Groves A. The internal and external boundaries of obsessive compulsive disorder. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;34:249-255.

Castle D., Phillips K.A. The obsessive-compulsive spectrum of disorders: a defensible construct? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;40:114-120.

Crino R., Slade T., Andrews G. The changing prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder criteria from DSM–III to DSM–IV. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:876-882.

Hollander E. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and spectrum across the lifespan. International Review of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2005;9:79-86.

Stein D.J., editor. Obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2006;29:343-613.