Chapter 26 The newborn infant

TRANSITION TO EXTRA-UTERINE LIFE

Changes in the pattern of blood circulation

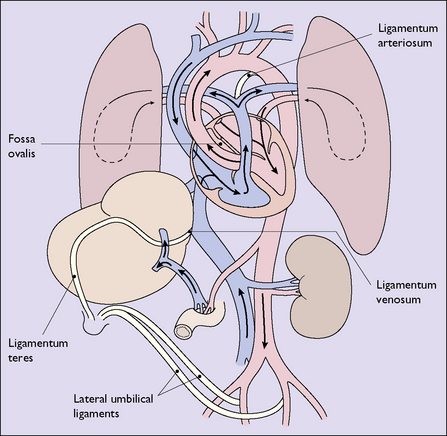

With the closure of the ductus venosus, the foramen ovale and the ductus arteriosus, the adult pattern of circulation of the blood is established (Fig. 26.1; compare with Fig. 4.1, p. 29).

PERINATAL HYPOXIA

Any condition occurring during late pregnancy or labour that reduces the oxygen available to the fetus will predispose it to cardiorespiratory and neurological depression at birth. These conditions have been mentioned when discussing the at-risk fetus in pregnancy and labour (see p. 152).

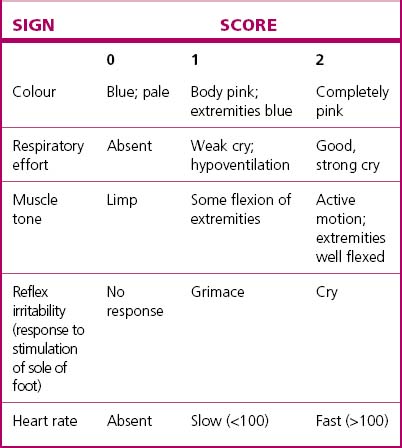

The severity of cardiorespiratory and neurological depression around the time of birth can be assessed by the Apgar scoring system (Table 26.1) or by the pH and/or blood lactate of umbilical artery blood. Both are useful in managing the immediate problem but are relatively poor indicators of long-term outcome.

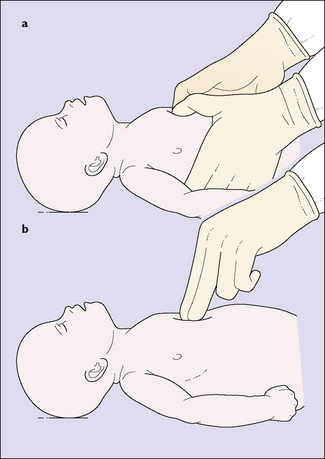

The basic resuscitation of the newborn is described on page 77 (see Fig. 8.15). The most important step in resuscitation is to initiate ventilation with intermittent positive-pressure respiration; current evidence suggests that ventilation using air (21% oxygen) should be the initial step for term babies, with oxygen being added only if hypoxia persists despite adequate ventilation. Initial ventilation should be with a mask and inflating device; failure to initiate spontaneous breathing within 2–5 minutes may require endotracheal intubation – but only if a person skilled in this technique is present. If the infant remains bradycardic (HR <60) despite adequate ventilation, the circulation should be supported by external cardiac massage (Fig. 26.2) and, possibly, endotracheal 1: 10 000 adrenaline 0.3–1.0 mL/kg. Once the umbilical vein is cannulated a further 0.1–0.3 mL/kg dose of adrenaline is given, and if there is no response further doses of adrenaline 0.1– 0.3 mL/kg can be given at 3–5-minute intervals.

BIRTH INJURIES

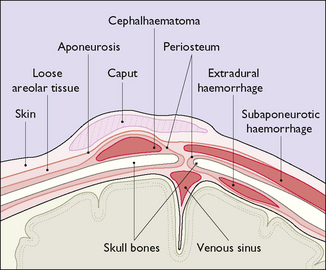

Cranial injuries (Fig. 26.3)

Subaponeurotic (subgaleal) haemorrhage

Subaponeurotic haemorrhage, while rare, occurs most commonly after a traumatic vacuum extraction (see p. 195–197) and may result in significant blood loss from the infant’s circulation. Occasionally the bleeding is very rapid and life-threatening and requires urgent blood transfusion. Frequent observation for diffuse head swelling following vacuum extraction is mandatory.

RESPIRATORY DISORDERS

Pneumonia

Pneumonia may be initially difficult to distinguish from other causes of respiratory distress so all babies with respiratory distress must have infection considered as a cause. Several different organisms may cause neonatal pneumonia, but group B streptococcus (see p. 137) may cause rapid deterioration and requires early treatment. Listeria monocytogenes is prevalent in some communities. Aspiration of meconium causes a chemical pneumonitis that can be life-threatening.

Management

NEONATAL INFECTIONS

Infections occurring during pregnancy that affect the fetus are discussed in Chapter 17. Infection may be acquired during labour, particularly if the membranes have been ruptured for a long time, or from vaginal colonisation by group B streptococci (GBS) (see p. 137). Acquired GBS infection may cause rapid onset of septicaemia, pneumonia ± meningitis within hours of birth.

Infections occurring after birth include:

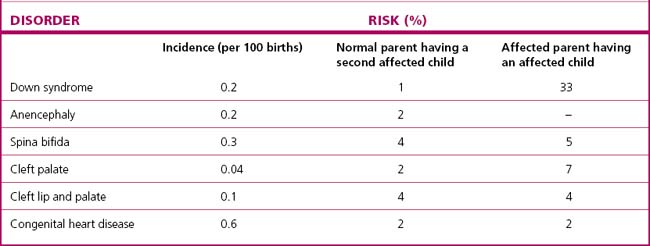

CONGENITAL MALFORMATIONS

Congenital malformations affect up to 3.5% of all infants. In about 2% of all infants such defects are major (Table 26.2). Many of the more severe structural abnormalities are now diagnosed antenatally during the 18-week morphology ultrasound scan, which gives the opportunity for counselling and discussion of the likely prognosis. When the diagnosis has been established the doctor should talk with the parents, explaining the malformation and the prognosis calmly and sympathetically. Most parents go through a grieving period. They may express anger and guilt, questioning whether anything they did or did not do during the pregnancy caused the malformation. Most appreciate counselling sessions.

Table 26.2 Order of prevalence of 28 selected birth defects: Victoria, Australia 2005–6

| Defect | N/10 000 | 1 IN N Births & Tops† |

|---|---|---|

| Hypospadias* | 74 | 135 |

| Obstructive defects of renal pelvis | 40 | 250 |

| Ventricular septal defect | 32.2 | 311 |

| Trisomy 21 | 29.5 | 339 |

| Developmental dysplasia of hip | 27.5 | 364 |

| Trisomy 18 | 8.4 | 1190 |

| Hydrocephalus | 8.1 | 1235 |

| Cleft palate | 8.0 | 1250 |

| Cystic kidney | 6.8 | 1471 |

| Renal agenesis/dysgenesis | 6.6 | 1515 |

| Transposition of great vessels | 6.3 | 1587 |

| Spina bifida | 6.0 | 1667 |

| Cleft lip and palate | 5.5 | 1818 |

| Anencephaly | 5.5 | 1818 |

| Coarctation of aorta | 4.9 | 2041 |

| Limb reduction defects | 4.8 | 2083 |

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome | 4.5 | 2222 |

| Anorectal atresia and/or stenosis | 4.4 | 2273 |

| Trisomy 13 | 3.9 | 2564 |

| Cleft lip | 3.9 | 2564 |

| Oesophageal atresia and/or stenosis | 3.8 | 2632 |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | 3.7 | 2703 |

| Exomphalos | 3.1 | 3226 |

| Intestinal atresia and/or stenosis | 3.2 | 3125 |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | 2.8 | 3571 |

| Gastroschisis | 2.3 | 4348 |

| Microcephalus | 1.8 | 5556 |

| Encephalocele | 1.2 | 8333 |

* Per male babies. From Riley M & Halliday J, Birth Defects in Victoria 2005–2006, Victorian Perinatal Data Collection Unit, Victorian Government Department of Human Services, Melbourne, 2008, with permission.

† Terminations of pregnancies.

The major malformations are described below.

Central nervous system defects

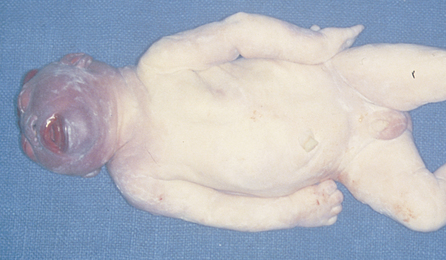

Anencephaly (Fig. 26.4) and spina bifida (Fig. 26.5) can be diagnosed in pregnancy, as described on page 43. Hydrocephalus can be diagnosed in the second half of pregnancy by ultrasound scanning, but may only be noticed when delivery is difficult.

Musculoskeletal defects

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) (including congenital dislocation) is characterized by an anteverted femoral head and neck and a shallow acetabulum, from which the femoral head may be partially or completely displaced. Between 1 and 3% of neonates show evidence of instability of the hip at birth, but in most cases this resolves spontaneously within a week or two. It is more common in females, in breech presentations and where there is a family history of DDH. In a few infants (1.5 per 1000) the defect persists. Examination of the newborn for congenital hip dislocation is described in Box 9.1, page 87. Any suspicion of congenital dislocation or subluxation of the hip is referred for an ultrasound examination; if confirmed, treatment is placement of the hips in abduction under specialist orthopaedic supervision.

Urogenital defects

Atresia of the kidneys is rare and fatal, presenting antenatally with oligohydramnios.

Down syndrome (Trisomy 21)

Down syndrome is the most common genetic defect. The infant may have slanting eyes with epicanthic folds, short hands, small fingers, simian creases of the palms and increased spacing between the first and second toes; the head is flattened at the back, the neck short and webbed, (Fig. 26.6). Generalized hypotonia is a characteristic finding. Most Down syndrome children have a lower than average cognitive ability, often ranging from mild to moderate impairment; a small number have severe to profound mental disability. There may be associated congenital anomalies – most commonly cardiac or gastrointestinal, but any system may be involved.

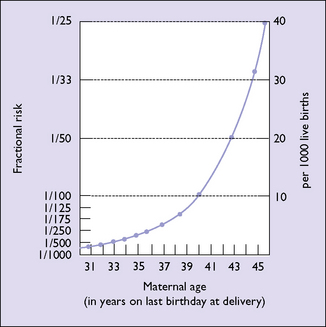

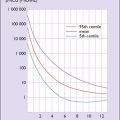

The incidence of Down syndrome increases with the age of the mother (Fig. 26.7). As mentioned in Chapter 6 (p. 42), Down syndrome can now be diagnosed by routine screening in over 80% of cases in early pregnancy, and termination offered.