CHAPTER 97 THE NEUROLOGICAL VASCULITIDES

Disorders caused by immunological or inflammatory disturbances affecting the nervous system account for a wide range of neurological diseases. They include primary or idiopathic neuroimmune disorders, which may affect any part of the neuraxis (e.g., multiple sclerosis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, myasthenia gravis) and which are common and familiar territories for the working neurologist. However, secondary disorders, in which the neurological disturbance reflects involvement of the nervous system in a (conventionally) systemic inflammatory process, although often no less common, infrequently manifest or behave in the ordered and predictable clinical manner of proper neurological diseases. Neurosarcoidosis, central nervous system (CNS) lupus, vasculitis, and neuro-Behçet’s disease all occasionally mimic one another, pursue erratic and unpredictable clinical courses, and confine themselves wholly to the nervous system, which renders diagnosis by tissue biopsy hazardous and unattractive; they evade the cautious diagnostician, and they confound the evidence-based therapist. This chapter provides a brief overview only of vasculitic diseases or vasculitides, which are more than capable of harboring most of these unsociable habits and so strike particular anxiety in the heart of the neurologist. (Table 97-1)

TABLE 97-1 Immunological and Inflammatory Diseases of the Nervous System

| Site | Primary Disease |

|---|---|

| Brain (and spinal cord) | Multiple sclerosis |

| Spinal cord | Inflammatory myelitides |

| Stiff-person syndrome | |

| Peripheral nerve | Guillain-Barré syndrome and variants |

| Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy | |

| Multifocal motor neuropathy | |

| Myasthenia gravis | |

| Polymyositis | |

| Dermatomyositis | |

| Secondary Disease | |

| Vasculitides | |

| Lupus, rheumatoid disease; other connective tissue diseases, anticardiolipin syndromes | |

| Behçet’s disease | |

| Sarcoidosis | |

| Paraneoplasia | |

| Organ-specific autoimmune disease (e.g., celiac disease, Hashimoto’s disease) |

The vasculitides are a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by blood vessel inflammation, occasionally with additional, specific, and defining pathological features, together producing different but frequently overlapping clinical manifestations.1 The classic core histopathological change consists essentially of an inflammatory infiltrate within (not just around) the vessel wall, in association with destructive mural changes (fibrinoid necrosis), precipitating vascular occlusion and then infarction—microscopic or macroscopic—which in turn accounts for the clinical manifestations.

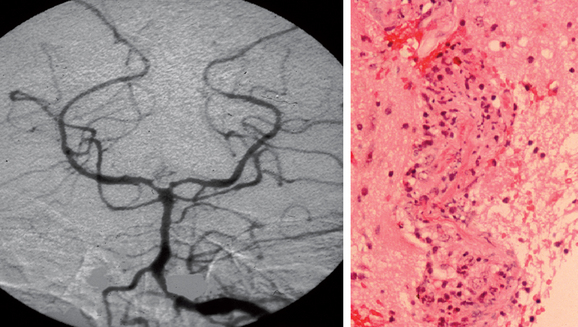

Classification of the vasculitides is complex, with subdivisions into idiopathic vasculitic disorders—for example, giant cell arteritis, polyarteritis, and Wegener’s granulomatosis—and vasculitis secondary to collagen diseases, malignancy, viral infection, drugs, and so forth. The histological characteristics allow further classification, including the presence or absence of granulomas and/or the size of the vessel implicated (Table 97-2; Fig. 97-1).

TABLE 97-2 Classification of the Vasculitides According to Size

| Dominant Vessel Involved | Primary | Secondary |

|---|---|---|

| Large arteries | Giant cell arteritis | Aortitis with rheumatoid disease; infection (e.g., syphilis) |

| Takayasu’s arteritis | Infection (e.g., hepatitis B) | |

| Medium arteries | Classic polyarteritis nodosa | |

| Kawasaki syndrome | ||

| Small vessels and medium arteries | Wegener’s granulomatosis | Vasculitis with rheumatoid disease, SLE, Sjögren’s syndrome, drugs, infection (e.g., HIV) |

| Churg-Strauss syndrome | ||

| Microscopic polyangiitis | ||

| Small vessels | Henoch-Schönlein purpura | Drugs (e.g., sulfonamides) |

| Essential cryoglobulinemia | Infection (e.g., hepatitis C) | |

| Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

MECHANISMS OF TISSUE DAMAGE

In both primary and secondary CNS and PNS vasculitis, the neurological features arise principally through ischemia and infarction. These in turn result from three consequences of inflammation within the vascular wall: obstruction of the vessel lumen, increased coagulation from the effects of proinflammatory cytokines on the endothelial surface, and alterations in vasomotor tone. The development of a vasculitic process depends on interplay between cellular and humoral factors; most research interest has centered on the latter.2

Antibody-Dependent Mechanisms

Direct Antibody Attack

In some systemic vasculitides, a pathogenic role for anti–endothelial cell antibodies in injuring or, paradoxically, activating endothelial cells is proposed,3 although their lack of specificity and variable frequency of detection do raise questions about any truly causal role. In rare cases, antibodies against amyloid-β deposits may precipitate cerebral vasculitis.4

Immune Complex–Mediated Vasculitis

Immune complex deposition in the blood vessel wall triggers complement activation, leading to polymorph and macrophage recruitment, amplification of inflammation, and the generation of lytic and injurious membrane attack complexes. Hepatitis B–and C–associated vasculitides are good examples of this process; the latter is found to underlie many cases of cryoglobulinemic vasculitis.5

Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody–Related Vasculitis

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) represent a family of antibodies directed against constituents of the neutrophil azurophil granules.6 Cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA) targets proteinase-3 and is associated with nearly 95% specificity for Wegener’s granulomatosis. Perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA), directed at myeloperoxidase, is less specifically found in patients with microscopic polyangiitis and Churg-Strauss syndrome.6 Such antibodies may play a significant role in generating and maintaining vascular inflammation.7,8

Cell-Mediated Damage

Evidence for cell-mediated involvement in tissue injury in vasculitis9 comes in part from studies of microscopic polyarteritis nodosa and of Wegener’s granulomatosis. In both disorders, circulating T cells responsive to proteinase-3 are found, and vascular lesions contain activated T cells and antigen-presenting major histocompatibility complex class II–positive dendritic cells. In primary CNS and PNS vasculitic lesions, the predominant infiltrate is one of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and monocytes.10

CAUSES OF NEUROLOGICAL VASCULITIS

Primary (Isolated) Angiitis of the Nervous System

In primary CNS vasculitis, there is no discernible recognized systemic vasculitic or, indeed, other disease, and vasculitis is confined to the brain and spinal cord. Although it is defined by this apparent exclusive distribution, autopsy studies have revealed subclinical extracranial involvement (e.g., of the pulmonary arteries and abdominal viscera11), which presumably helps explain the occasional features of fever, rigors, weight loss, raised plasma viscosity, and so forth.

The clinical definition of cerebral vasculitis is not uniform, and this helps explain significant differences in the approach to diagnosis and therapy. Some authorities have defined the disorder by its angiographic appearances,11a which implies that tissue confirmation is not needed. (Indeed, some authors have suggested a more favorable monophasic clinical course in the so-called benign angiopathy of the CNS. This is a syndrome with normal or only mildly abnormal CSF and evidence of vasculitis on angiography alone.12 The concept has been questioned, in view of the recognized nonspecificity of angiography, the fact that cases not proceeding to biopsy are more likely to be less severe, and because pediatric cases satisfying “benign angiopathy” criteria often do not have a temperate, monophasic course and have required aggressive immunotherapy.13) Most authorities, however, including this author, believe that a certain diagnosis of primary CNS angiitis must depend on a positive biopsy.

Primary PNS vasculitis closely parallels CNS disease. Otherwise termed nonsystemic vasculitic neuropathy, there is likewise no overt evidence of any recognizable vasculitic disorder elsewhere; however, authorities have varied in their definitions and in whether cases that include mild constitutional symptoms or serological abnormalities should be excluded.14 As with primary CNS disease, the arguments are finely balanced as to whether nonsystemic vasculitic neuropathy is truly an exclusively neurological disease or a systemic vasculitis in which the overwhelming burden of disease falls on the PNS.15–18 This is not merely an academic question, because upon it hinges (at least partly) the justification for extrapolating therapeutic data from the systemic vasculitides.

Primary Systemic Vasculitides with Neurological Involvement

Wegener’s granulomatosis predominantly affects the upper and lower respiratory tracts: the nose (often with destructive cartilaginous change that causes saddle nose deformity), sinuses, larynx, trachea, and lungs. Ocular involvement may occur, and renal disease occurs in 80% of affected patients. c-ANCA measurements are positive, with proteinase-3 specificity, and the biopsy findings are characteristic, with a necrotizing, granulomatous vasculitis. Neurological involvement occurs in up to 35% of affected patients19 but most commonly involves the PNS. Meningeal and middle ear disease may lead to significant cranial neuropathies (especially of nerves VII and VIII). Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is valuable in that it may reveal meningeal thickening and infiltration, which are ready targets for biopsy. Ocular involvement may occur with orbital pseudotumor. Cerebral small-vessel vasculitis is rare but, when it does occur, is usually responsible for encephalopathies, seizures, and pituitary abnormalities; however, this manifestation may be indistinguishable from that of any other form of intracranial vasculitis. More likely is the unique contiguous extension of erosive granulomas from the sinuses or from remote metastatic granulomas to the CNS.

Microscopic polyangiitis is a multisystem small-vessel vasculitis that has many similarities to Wegener’s granulomatosis, including pulmonary hemorrhage, but differs in that upper respiratory tract involvement is rare and granuloma formation is not seen. Affected patients usually have glomerulonephritis, and, indeed, this vasculitis is occasionally confined to the kidneys. In one study, mononeuritis multiplex was found in 55% of patients20; in this study, the brain was seldom affected (11%), and CNS disease did not contribute to mortality. There are, however, infrequent reports of p-ANCA–positive, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis associated with cerebral vasculitis, necessitating aggressive therapy.

Churg-Strauss syndrome is characterized by hypereosinophilia with systemic vasculitis, occurring in individuals with recently developed atopic features. Asthma and mononeuritis multiplex are frequent manifestations of this disease. Rashes, with purpura, urticaria, and subcutaneous nodules, are common. Glomerulonephritis may develop; it may also affect coronary, splanchnic, and cerebral circulations. CNS involvement is evident in only about 7% of affected patients.21 About 50% of patients are seropositive for p-ANCA, 25% are seropositive for c-ANCA, and 25% have no antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies.

Secondary Vasculitis: A Complication of “Nonvasculitic” Systemic Disorders

Autoimmune and Inflammatory Disease

Neurological or psychiatric symptoms in systemic lupus erythematosus (see Chapter 119) are common (40% to 50%),22 but the most frequent neuropathological finding is that of a noninflammatory vasculopathy of small arterioles and capillaries, with resulting microinfarcts and microhemorrhages. Histopathological studies have consistently demonstrated that vasculitis of the cerebral vessels is rare, with an incidence of 7% to 13%. Serological study naturally forms the mainstay of diagnosis.

Sarcoidosis (see Chapter 96) affects the nervous system in only 5% of cases, commonly manifesting with optic and other cranial neuropathies (especially involving the facial nerve) and usually caused by granulomatous meningeal and brainstem infiltration. Sarcoidosis may be complicated by systemic vasculitis affecting small- or large-caliber vessels in a manner similar to that of other vasculitides, with angiographic and, indeed, histological evidence of CNS vasculitis. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme and calcium levels are not always raised. CSF abnormalities are seen in 80% of affected patients, usually with an elevated protein level and pleocytosis, and oligoclonal bands are present in about 45%. Cranial MRI exhibits nonspecific multiple white matter lesions or meningeal enhancement; whole-body gallium scanning can be more useful, demonstrating a characteristic pattern of uptake (affecting the parotid glands and lungs in particular). Pathological diagnosis by the Kveim test or, better still, by biopsy of cerebral or meningeal tissue provides the most reliable basis for treatment.23

Seropositive rheumatoid disease is a well-recognized precipitant of cerebral vasculitis, although skin involvement and mononeuritis multiplex are far more typical manifestations of rheumatoid vasculitis.22 There are unusual reports of CNS angiitis in the context of systemic sclerosis, Sjögren’s syndrome, and mixed connective tissue disease, even (although rarely) without a preceding history of systemic symptoms.

Behçet’s disease is caused predominantly by vasculitis affecting small- and medium-sized vessels (see Chapter 96).

Infections

Numerous infectious agents have been implicated in primary invasion of the vascular wall, a more direct infection-associated vasculitis.24 Aspergillus, Histoplasma, and Coccidioides species are among the fungal causes, usually confined to immunosuppressed patients and patients with diabetes mellitus. In human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, cytomegalovirus and Toxoplasma infection may precipitate vasculitis, and syphilitic cerebral vasculitis has also reemerged in the context of HIV infection. Bacterial causes of meningoencephalitis—Mycobacteria, pneumococci, and Haemophilus influenzae—may also trigger intracranial vasculitis.

One infection that merits particular attention in this context is herpes zoster ophthalmicus. This can cause secondary, localized CNS vasculitis that affects the ipsilateral hemisphere, probably by direct viral invasion of blood vessels,25 producing single or multiple smooth-tapered segmental narrowing on angiography. The characteristic clinical picture, seen in approximately 0.5% of cases, is that of an acute monophasic hemiparesis contralateral to the (usually by now resolving) ocular disease. The latent period may last from days to months but is usually approximately 3 to 4 weeks. The presence of mononuclear pleocytosis and raised varicella-zoster antibody titer aids the diagnosis. A more generalized necrotizing and granulomatous vasculitis can also occur.

Chronic viral infection with parvovirus B19 has been implicated in polyarteritis nodosa, Kawasaki syndrome, and Wegener’s granulomatosis, although causality is by no means proved.24 Tuberculosis-associated vasculitis may be driven by tuberculoprotein immune complexes. Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and the viruses that cause hepatitis B, Lyme disease, syphilis, and malaria cause vasculitis by a similar mechanism, whereas in coccidioidomycosis, vascular inflammation occurs either directly or through cryoglobulinemia.

Malignancy, Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis, and Malignant Angioendothelioma

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may occur in association with a variety of cancers as a paraneoplastic phenomenon. CNS disease in the context of Hodgkin’s disease with a pathological picture indistinguishable from conventional isolated CNS angiitis has been reported.25a Lymphomatoid granulomatosis is a lymphomatous disorder centered on the vascular wall, with destructive change and secondary inflammatory infiltration lending the appearance of true vasculitis; the infiltrating neoplastic cell is of T lymphocyte derivation. Cutaneous and pulmonary involvement is common, with nodular cavitating lung infiltrates, and neurological manifestations occur in 25% to 30% of cases; they are the manifesting feature in approximately 20%. Neoplastic or malignant angioendotheliomatosis is also a rare, nosologically separate disorder, wherein the neoplastic process is intravascular (i.e., within the lumen) and the lymphomatous cells are B cell derived and characteristically do not invade the vascular wall. The neurological features of each disorder are similar, largely representing those of cerebral vasculitic disease; in malignant angioendotheliomatosis, lung involvement is not the rule; characteristic skin manifestations occur.

Drug- and Toxin-Induced Cerebral Vasculitides

The most compelling evidence of a direct association is related to amphetamines, with clinical and histological evidence of multisystem necrotizing vasculitis.26 In humans, vasculitis may occur after only a single dose of amphetamine, but repeated exposure in young adults is the usual history. However, in many other reports of drug-induced vasculitis, there is no tissue confirmation, and the diagnosis of “vasculitis” is based on angiography, despite the fact that vasospasm can cause angiographic changes identical to those of vasculitis.26a In cocaine abuse, the significantly increased risk of ischemic stroke results from vasospasm (probably caused by increased catecholamine release) and very seldom from any form of vasculitis.27 In intravenous abuse, concomitantly injected contaminants such as hepatitis C virus may cause vasculitis.

In rare cases, an immune reaction against (spontaneous) amyloid deposits within the cerebral vasculature appears to precipitate a true CNS vasculitis, a recently described disorder that has been termed Aβ-related angiitis.4

CEREBRAL VASCULITIS

The Clinical Features of Central Nervous System Vasculitis

Focal or multifocal infarction or diffuse ischemia, affecting any part of the brain, explains the protean manifestations; the wide variations in disease activity, course, and severity; and the absence of a pathognomonic or even typical clinical picture. Most accounts of both primary and secondary intracranial vasculitides describe headaches, focal or generalized seizures, strokelike episodes with hemispherical or brainstem deficits, acute or subacute encephalopathies, progressive cognitive changes, chorea, myoclonus and other movement disorders, and optic and other cranial neuropathies.28–30 The course is commonly acute or subacute, but chronic progressive manifestations are also well described, as are spontaneous relapses and remissions. Systemic features such as fever, night sweats, livedo reticularis, or oligoarthropathy may also be present (often revealed only through direct questioning).

Despite the diversity of neurological manifestation, three broad categories (not intended to carry either pathological or therapeutic differences) have been defined in one small study31; these may help to improve recognition of the condition:

Diagnosis and Management

Many other disorders, of course, may also cause a combination of headache, encephalopathy, strokes, seizures, and focal deficits of acute or subacute onset (Table 97-3). The diagnosis of cerebral vasculitis therefore first involves the exclusion of alternative possibilities, before confirmation of intracranial vasculitis and followed by pursuit of the cause of the vasculitic process. No single simple investigation can confirm a diagnosis of cerebral vasculitis; some can rule it out.

TABLE 97-3 Some Neurological and Systemic Disorders That May Mimic Cerebral Vasculitis

ADEM, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CADASIL, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy.

Blood Tests and Serology

Anemia is an infrequent finding, and a leukocytosis without eosinophilia is present in about 50% of affected patients. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein levels are often abnormal, especially in cases secondary to systemic disease, but of course lack specificity. (Some authorities include a normal ESR as a defining feature of primary angiitis of the central nervous system [PACNS]; others report moderately elevated values in two thirds of patients.28–30) Serological testing (e.g., antinuclear antibody, ANCA) is vital for ruling out lupus or helping define any systemic origin of an established intracranial vasculitis, but it is of little value in confirming or refuting isolated cerebral vasculitis. “False” ANCA positivity is sometimes seen in connective tissue disorders such as lupus and, rarely, in individuals with no apparent vasculitic disorder at all.

Spinal Fluid Examination

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis is nonspecific but, again, useful in implying an inflammatory process within the CNS and ruling out infection and malignant diseases that may manifest similarly. Pooled case reviews suggest an elevation in cell count (mainly a lymphocytosis) and protein in 50% to 80% of affected patients.28–30 The CSF opening pressure is raised in almost one half of PACNS cases. Oligoclonal immunoglobulin bands in the CSF have been studied infrequently but are found frequently enough (perhaps in 40% to 50% of patients31) to warrant consideration of analysis. Oligoclonal band patterns that vary substantially, perhaps even disappearing altogether during the course of disease, do help point away from multiple sclerosis when this is part of the differential diagnosis.

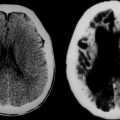

Radiography

MRI is a sensitive but not specific detector of vascular disease32; it discloses, of course, the results of vascular inflammation but not vasculitis itself. Ischemic areas, periventricular white matter lesions, hemorrhagic lesions, and parenchymal or meningeal enhancing areas can be seen. Correlation between MRI changes and blood vessel involvement may be poor: In one study, of 50 territories affected by vasculitis on contrast-enhanced angiography, at least one third appeared normal on MRI.33 Other studies confirm this imperfect sensitivity, and there are (unfortunately) reported cases of proven cerebral vasculitis with normal-appearing MRI.

Single photon emission computed tomography appears to be a useful but nonspecific imaging tool, again mirroring but not defining a vasculitic process.31 The value of positron emission tomographic scanning in this context has yet to be clarified.

Magnetic resonance angiography has a niche in imaging of large-vessel vasculitides such as Takayasu’s arteritis and classic periarteritis nodosa, with potential to supplant contrast-enhanced angiography,34 but does not have sufficient resolution to offer great value in evaluating medium- or small-vessel cranial vasculitis.

Establishing the diagnostic value of contrast-enhanced angiography is complicated by the many studies in which investigators have used this as the “gold standard” for confirmation. Studies with pathological evidence indicate that angiography yields a false-negative rate of 30% to 40%,29,30 and there have been examples of patients with histologically proven PACNS who have completely normal-appearing angiograms. The explanation may be that the resolution of conventional imaging is not sufficient for the affected vessels.

When abnormalities are present, they include segmental (often multifocal) narrowing with areas of localized dilatation or beading (see Fig. 97-1). Single stenotic areas in multiple vessels are more frequent than multiple stenotic areas along a single vessel segment in PACNS. Retrospective series30,35 suggest that the sensitivity is only 24% to 33%, and the specificity is of a similar order; an enormous number of inflammatory, metabolic, malignant, or other vasculopathies can closely mimic angiitis. Some authors have reported a risk of transient (in 10% of patients) or permanent neurological deficit (in 1%).36 Although its importance has been overemphasized, contrast-enhanced angiography remains a valuable investigational tool with a sensitivity comparable with that of biopsy.

Indium-labeled white blood cell nuclear scanning has a limited role, particularly in disclosing areas of (sometimes unsuspected) systemic inflammation.31

Ophthalmological Examination

Careful ocular examination, including slit-lamp study, forms a vital part of the assessment of patients with suspected cerebral vasculitis. On occasion, subclinical conjunctival, anterior, or posterior inflammation or retinal changes, through conjunctival biopsy, confirm ocular (and thereby imply neurological) sarcoidosis, Behçet’s syndrome, or other inflammatory disorders. Dynamic recording of erythrocyte flow, with video slit-lamp microscopic recording and low-dose fluorescein angiography to examine the vasculature of the anterior ocular chamber, can be a useful additional investigation.31

Histopathology

Histopathological confirmation is important and may be made through biopsy of an abnormal area of the brain where possible or through “blind” biopsy, incorporating meninges and nondominant temporal white and gray matter. Biopsy may reveal an underlying process not otherwise suspected with profound therapeutic implications, such as infective or neoplastic (principally lymphomatous) vasculopathies; however, it is not a trivial procedure, inasmuch as it carries a risk of serious morbidity estimated at 0.5% to 2%. Sensitivity is limited to (at best) approximately 70%.29,30,35 Nevertheless, the significant risk means that up to 75% of reported cases are “diagnosed” without histopathological confirmation.11

A retrospective study of 61 patients undergoing biopsy for suspected cerebral vasculitis has usefully illuminated this topic.35 No patients suffered any significant morbidity as a result of the procedure. Thirty-six percent of patients were confirmed as having cerebral vasculitis, but, in an equally useful and important finding, 39% of biopsies revealed an alternative, unsuspected diagnosis: lymphoma (six cases), multiple sclerosis (two cases), and infection (seven cases, including toxoplasmosis and herpes and also, in two cases, cerebral abscess). Many of these nonvasculitic disorders are treatable, often indeed curable, but inappropriate treatment with steroids alone or with more potent immunosuppressive agents would have at best no useful effect and very often serious adverse consequences. Biopsy failed to yield a clear diagnosis in 25% of patients in this study; however, even in these cases, biopsy arguably might not be described as “noncontributory,” because it at least helped rule out the alternative diagnoses mentioned. The decision not to biopsy must be balanced against the harmful effects of immunosuppressive drugs used, potentially, unnecessarily.

The Treatment of Cerebral Vasculitis

Notwithstanding the problems in recognition and diagnosis, cerebral vasculitis is considered a highly treatable condition. Prospective controlled randomized trials are lacking because of the rarity of the condition and the absence of unifying diagnostic criteria. Retrospective analyses have been the main study tool, and they, together with lessons from systemic vasculitides,37 have provided significant support for the use of steroids with cyclophosphamide in confirmed cases.38

Cyclophosphamide is associated with hemorrhagic cystitis (a complication reduced by adequate hydration and mesna cover), a 33-fold increase in bladder cancer, other malignancies, infertility, cardiotoxicity, and pulmonary fibrosis. In a study of 145 patients treated with this agent for systemic Wegener’s disease and monitored for a total of 1333 patient-years, nonglomerular hematuria occurred in approximately 50%, the majority of whom had macroscopic changes consistent with cyclophosphamide-induced bladder injury evident on cystoscopy. Seven of these (and none without hematuria) developed transitional cell bladder carcinoma; six had had a total cumulative cyclophosphamide dose exceeding 100 g and a duration of oral treatment exceeding 2.7 years.39

Deterioration, failure to respond initially, or intolerance of this regimen may necessitate the use of alternative agents. Methotrexate at 10- to 25-mg doses on a weekly basis may be used in conjunction with steroids, during either induction or maintenance. Intravenous immunoglobulin (0.4 mg/kg/day for 5 days), with its good safety record, has been found useful in cases of systemic vasculitis, although it may induce only partial remission.40

Plasmapheresis may be valuable in cryoglobulinemia. It is also considered in severe life-threatening disease (e.g., pulmonary hemorrhage and severe glomerulonephritis), with 7 to 10 treatments over 14 days.41 Although there is little experience with its use in patients with intracranial disease, there is evidence of significant improvement when it is used in combination with steroids in cerebral disease associated with Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

A number of monoclonal antibodies, directed against CD52 (present on most lymphocytes), CD20 (B cells), or tumor necrosis factor, are generating much excitement as novel therapies in various inflammatory diseases, including the vasculitides; paradoxically, however, the induction of vasculitis has also been reported with some of these agents.42–46 Interferon α can control not only hepatitis C–associated hepatitis but also cryoglobulinemia and vasculitis. Unfortunately, there frequently a relapse within months of treatment withdrawal.

GIANT CELL VASCULITIDES

Classically, it manifests as temporal headache with tender, pulseless, nodular temporal arteries and, often described only after direct inquiry, symptoms of general malaise, jaw claudication, and features of polymyalgia rheumatica (stiffness and aching of the shoulder girdle, worse in the mornings, and occasionally general malaise). Neuro-ophthalmological symptoms are the most widely recognized; blindness occurs in one sixth of treated patients with the condition.47 This occurs as a consequence of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy after vasculitic involvement of the posterior ciliary arteries and/or the ophthalmic artery, from which they are derived. The typical picture comprises locally painless loss of acuity, commonly severe, often with an altitudinal field defect. The fundal appearances may be normal, although swelling, usually mild, may be present. Conventionally, the inflammatory process is believed to involve only the extracranial vessels and rarely to extend beyond the point of penetration of the dura. A large study of 166 patients with biopsy-proved temporal arteritis demonstrated neurological involvement in 31%, describing the usual comprehensive range of neurological manifestation: neuropsychiatric syndromes, peripheral neuropathies, mononeuropathies, spinal cord lesions, neuro-otological syndromes, various pain syndromes, transient ischemic attacks, and stroke. Most authorities, however, would find almost all these manifestations outside their common experience.47 Infarction of the vertebrobasilar territory is relatively uncommon, but there have been isolated reports of temporal arteritis manifesting as lateral medullary syndrome. The expected greater incidence of cerebrovascular disease in this older subgroup may, however, be confounding.

The ESR may be used to monitor treatment response. However, it has been pointed out that a low ESR in active disease is not excessively rare and perhaps may be explained by an inability to mount an acute phase response or by very localized arteritis.48 Measuring serum interleukin-6 levels is a promising alternative to the ESR. Investigators have also emphasized that an elevated platelet count should be considered a risk factor for permanent visual loss in temporal arteritis and should accentuate the need for urgent treatment.49

VASCULITIS OF THE PERIPHERAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

In comparison with the clinical picture and diagnosis of CNS disease, those of PNS vasculitis are relatively straightforward. Up to 50% of patients present with mononeuritis multiplex; the remainder present with a more diffuse asymmetrical or a distal symmetrical polyneuropathy. Usually there are mixed sensory and motor features, which are very commonly painful and progress rapidly.15–18 Other causes of multiple focal large-nerve palsies must not be forgotten; these range from common disorders, such as diabetes mellitus, to the less common, such as hereditary liability to pressure palsies, lead poisoning, sarcoidosis, HIV infection, and paraneoplasia. As outlined previously, involvement of the PNS is substantially commoner than that of the CNS in the systemic vasculitides.

Lie JT. Classification and histopathologic spectrum of central nervous system vasculitis. Neurol Clin. 1997;15:805-819.

Schmidley JW. Central and Peripheral Nervous System Angiitis. Oxford, UK: Butterworth Heinemann, 2000.

Scolding NJ. Immunological and Inflammatory Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1999.

1 Watts RA, Scott DG. Classification and epidemiology of the vasculitides. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1997;11:191-217.

2 Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Milling DM. Pathogenesis of vasculitis. Semin Neurol. 1994;14:291-299.

3 Salojin KV, Le TM, Nassovov EL, et al. Anti-endothelial cell antibodies in patients with various forms of vasculitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1996;14:163-169.

4 Scolding NJ, Joseph F, Kirby PA, et al. Aβ-related angiitis: primary angiitis of the central nervous system associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 3):500-515.

5 Cacoub P, Maisonobe T, Thibault V, et al. Systemic vasculitis in patients with hepatitis C. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:109-118.

6 Mohan N, Kerr GS. Diagnosis of vasculitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2001;15:203-223.

7 Harper L, Williams JM, Savage CO. The importance of resolution of inflammation in the pathogenesis of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:502-506.

8 Xiao H, Heeringa P, Hu P, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies specific for myeloperoxidase cause glomerulonephritis and vasculitis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:955-963.

9 Mathieson PW, Oliveira DB. The role of cellular immunity in systemic vasculitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;100:183-185.

10 Lie JT. Biopsy diagnosis of systemic vasculitis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1997;11:219-236.

11 Lie JT. Classification and histopathologic spectrum of central nervous system vasculitis. Neurol Clin. 1997;15:805-819.

11a Scolding NJ, Wilson H, Hohlfeld R, et al. The recognition, diagnosis and management of cerebral vasculitis: a European survey. Eur J Neurol. 2002;9:343-347.

12 Calabrese LH, Gragg LA, Furlan AJ. Benign angiopathy: a subset of angiographically defined primary angiitis of the central nervous system. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:2046-2050.

13 Gallagher KT, Shaham B, Reiff A, et al. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system in children: 5 cases. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:616-623.

14 Collins MP, Periquet MI. Nonsystemic vasculitic neuropathy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17:587-598.

15 Collins MP, Periquet MI, Mendell JR, et al. Nonsystemic vasculitic neuropathy: insights from a clinical cohort. Neurology. 2003;61:623-630.

16 Davies L, Spies JM, Pollard JD, et al. Vasculitis confined to peripheral nerves. Brain. 1996;119:1441-1448.

17 Dyck PJ, Benstead TJ, Conn DL, et al. Nonsystemic vasculitic neuropathy. Brain. 1987;110:843-854.

18 Said G, Lacroix-Ciaudo C, Fujimura H, et al. The peripheral neuropathy of necrotizing arteritis: a clinicopathological study. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:461-465.

19 Nishino H, Rubino FA, DeRemee RA, et al. Neurological involvement in Wegener’s granulomatosis: an analysis of 324 consecutive patients at the Mayo Clinic. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:4-9.

20 Guillevin L, Durand-Gasselin B, Cevallos R, et al. Microscopic polyangiitis: clinical and laboratory findings in eighty-five patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:421-430.

21 Sehgal M, Swanson JW, DeRemee RA, et al. Neurologic manifestations of Churg-Strauss syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:337-341.

22 Scolding NJ. Neurological complications of rheumatological and connective tissue disorders. In: Scolding NJ, editor. Immunological and Inflammatory Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1999:147-180.

23 Zajicek JP, Scolding NJ, Foster O, et al. Central nervous system sarcoidosis—diagnosis and management. QJM. 1999;92:103-117.

24 Lie JT. Vasculitis associated with infectious agents. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1996;8:26-29.

25 Hilt DC, Buchholz D, Krumholz A, et al. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus and delayed contralateral hemiparesis caused by cerebral angiitis: diagnosis and management approaches. Ann Neurol. 1983;14:543-553.

25a Greco FA, Kolins J, Rajjoub RK, Brereton HD. Hodgkin’s disease and granulomatous angiitis of the central nervous system. Cancer. 1976;38:2027-2032.

26 Citron BP, Halpern M, McCarron M, et al. Necrotizing angiitis associated with drug abuse. N Engl J Med. 1970;283:1003-1011.

26a Nolte KB, Brass LM, Fletterick CF. Intracranial hemorrhage associated with cocaine abuse: a prospective autopsy study. Neurology. 1996;46:1291-1296.

27 Aggarwal SK, Williams V, Levine SR, et al. Cocaine-associated intracranial hemorrhage: absence of vasculitis in 14 cases. Neurology. 1996;46:1741-1743.

28 Scolding NJ. Cerebral vasculitis. In: Scolding NJ, editor. Immunological and Inflammatory Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1999:210-258.

29 Calabrese LH, Mallek JA. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Report of 8 new cases, review of the literature, and proposal for diagnostic criteria. Medicine. 1988;67:20-39.

30 Hankey G. Isolated angiitis/angiopathy of the CNS. Prospective diagnostic and therapeutic experience. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1991;1:2-15.

31 Scolding NJ, Jayne DR, Zajicek JP, et al. The syndrome of cerebral vasculitis: recognition, diagnosis and management. QJM. 1997;90:61-73.

32 Harris KG, Tran DD, Sickels WJ, et al. Diagnosing intracranial vasculitis: the roles of MR and angiography. Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:317-330.

33 Cloft HJ, Phillips CD, Dix JE, et al. Correlation of angiography and MR imaging in cerebral vasculitis. Acta Radiol. 1999;40:83-87.

34 Atalay MK, Bluemke DA. Magnetic resonance imaging of large vessel vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13:41-47.

35 Alrawi A, Trobe J, Blaivas M, et al. Brain biopsy in primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Neurology. 1999;53:858-860.

36 Hellmann DB, Roubenoff R, Healy RA, et al. Central nervous system angiography: safety and predictors of a positive result in 125 consecutive patients evaluated for possible vasculitis. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:568-572.

37 Jayne D, Rasmussen N, Andrassy K, et al. A randomized trial of maintenance therapy for vasculitis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:36-44.

38 Scolding NJ, Wilson H, Hohlfeld R, et al. The recognition, diagnosis and management of cerebral vasculitis: a European survey. Eur J Neurol. 2002;9:343-347.

39 Talar-Williams C, Hijazi YM, Walther MM, et al. Cyclophos-phamide-induced cystitis and bladder cancer in patients with Wegener granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:477-484.

40 Jayne DR, Chapel H, Adu D, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for ANCA-associated systemic vasculitis with persistent disease activity. QJM. 2000;93:433-439.

41 Gaskin G, Pusey CD. Plasmapheresis in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated systemic vasculitis. Ther Apher. 2001;5:176-181.

42 Booth A, Harper L, Hammad T, et al. Prospective study of TNFα blockade with infliximab in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated systemic vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:717-721.

43 Unger L, Kayser M, Nusslein HG. Successful treatment of severe rheumatoid vasculitis by infliximab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:587-588.

44 Mathieson PW, Cobbold SP, Hale G, et al. Monoclonal-antibody therapy in systemic vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:250-254.

45 Mohan N, Edwards ET, Cupps TR, et al. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis associated with tumor necrosis factor-α blocking agents. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1955-1958.

46 Sneller MC. Rituximab and Wegener’s granulomatosis: are B cells a target in vasculitis treatment? Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1-5.

47 Caselli RJ, Hunder GG. Neurologic complications of giant cell (temporal) arteritis. Semin Neurol. 1994;14:349-353.

48 Salvarani C, Hunder GG. Giant cell arteritis with low erythrocyte sedimentation rate: frequency of occurrence in a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45:140-145.

49 Lincoff NS, Erlich PD, Brass LS. Thrombocytosis in temporal arteritis rising platelet counts: a red flag for giant cell arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2000;20:67-72.