chapter 2

The Neurological History

This chapter will endeavour to provide a basic understanding of the principles of history taking so that the time spent on the ward learning how to take a history can be more effective, more interesting and more enjoyable. In particular, the pivotal aspects of clinical neurology will be discussed.

• Where is the lesion? Is the problem in the cerebral hemispheres, brainstem, cerebellum, spinal cord, nerve roots, brachial or lumbosacral plexus, peripheral nerve, neuromuscular junction or muscle? When considering the nature (i.e. whether it is weakness, sensory symptoms or visual or speech disturbances) and the distribution of the weakness and sensory symptoms in terms of which parts of the body are affected, thinking about the underlying neuroanatomy will help to localise the problem within the nervous system.

• What is the pathology? Establish the mode of onset and progression of the illness.

and family history of migraine was used to make a diagnosis of migraine. This patient’s symptoms were of instantaneous onset and were related to a ruptured berry aneurysm causing subarachnoid haemorrhage (bleeding into the subarachnoid space – the space beneath the outer lining of the brain, referred to as the dura mater, and the surface of the brain).

A past history of a medical problem does not preclude the patient suffering from

a totally unrelated illness. The approach of using the past history to influence the diagnosis of the current problem often leads to a delay in diagnosing new problems in patients with chronic diseases. In most instances ‘prior probability’ is correct, and this can lull clinicians into thinking that they are clever when in fact it was difficult for them to be wrong even if they did not obtain a detailed history. Typical examples of this are an older person with a hemiparesis with the most likely cause being a stroke and the general practitioner (GP) who diagnoses most patients as having a tension-type headache and is correct the vast majority of the time simply because most patients attending a GP with headache do in fact suffer from tension-type headache.

Spencer [1] stated that it is not possible to learn how to take an effective history from a textbook. The clinical environment is the only setting in which the skills of history taking, physical examination, clinical reasoning, decision making, empathy and professionalism can be taught and learnt as an integrated whole. Although this is correct, one could use the analogy of learning to play golf: you can either hack away for years to teach yourself or you can have lessons that will make the practice more effective.

Traditionally, students have been taught to ask a long list of neurological questions about headache, dizziness, weakness, numbness etc in the forlorn hope that, after this ‘fishing expedition’ (also referred to as ‘looking for the pony’1) [2], a diagnosis will be apparent. In other words, in the hope of finding the diagnosis (‘the pony’), one collects a large list of answers to numerous specific questions that largely relate to the nature of the symptoms with little understanding about what the answers represent. It has been suggested that students should be taught to take a history this way and then taught not to take it that way. I disagree. I would like to recommentd that students should be taught how to take a history in a way that is meaningful to them rather than just collecting useless information they do not know how to use.

PRINCIPLES OF NEUROLOGICAL HISTORY TAKING

An alternative method of obtaining the history in patients presenting with intermittent disturbances of neurological function or recurrent episodes, e.g. epilepsy or headache, is recommended. In essence, with intermittent disturbances it is better to obtain a blow-by-blow description of several individual episodes. This alternative approach is described in Chapter 7, ‘Episodic disturbances of neurological function’ and Chapter 8, ‘Seizures and epilepsy’.

1. Define the likely underlying pathological basis by eliciting the mode of onset, progression and duration of each and every symptom (i.e. the time course of the illness).

2. Establish the site of the disorder within the nervous system by determining the nature and distribution of symptoms.

3. Elicit other facts that may either establish a cause for the problem or, more importantly, influence subsequent management of the patient. This includes the family history, past history, coexistent medical problems, prescribed drugs and natural remedies the patient is taking, social factors and the patient’s concerns.

THE UNDERLYING PATHOLOGICAL PROCESS: MODE OF ONSET, DURATION AND PROGRESSION OF SYMPTOMS

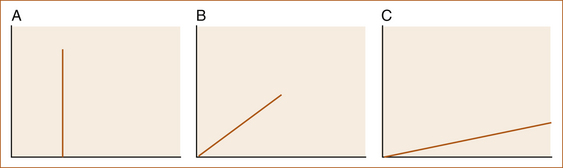

Different pathological processes evolve over variable periods of time and it is this variability that can be used to determine the most likely pathology. Three modes of onset can be loosely defined: sudden onset within seconds to minutes, gradual onset over hours to days and a very gradual onset over months to years (see Figure 2.1). The expression ‘mode of onset’ refers to the time for all symptoms to FULLY develop in terms of either their intensity and/or their distribution.

The pathological processes that reflect these modes of onset are:

A Instantaneous – seconds, rarely minutes

• Electrical: an epileptic seizure or an arrhythmia such as a tachyarrhythmia (fast heart beat), bradyarrhythmia (slow heart beat) or complete heart block (no impulse between the right atrium and ventricles, the Stokes–Adams attack)

• Vascular: subarachnoid haemorrhage, cerebral embolus

• Mechanical: trauma, a slipped intervertebral disc or positional vertigo

• Infective: meningitis, encephalitis

• Inflammatory: multiple sclerosis, acute inflammatory neuropathies

• Neoplastic: benign and occasionally malignant tumours

• Degenerative: cervical spondylitic myelopathy and the various genetic disorders

• Chronic endocrine problems: hypothyroidism, Cushing’s disease, pituitary disorders

• Chronic inflammatory/infective processes: polymyositis, chronic inflammatory demyelinating peripheral neuropathies, cryptococcal or tuberculous meningitis

Exceptions to the rule include:

• Symptoms such as diplopia (double vision) and vertigo will, as a result of their very nature, always begin abruptly and need not necessarily indicate a pathological process with a vascular or mechanical basis (see the section ‘The nature and distribution of symptoms’).

• At time, neoplastic disorders can present with a very rapid evolution of symptoms as a result of a seizure and the rapid onset of a focal neurological deficit after the seizure; tumours can also appear to evolve more rapidly when there is a superimposed mechanical shift due to the mass effect.

• Vascular disorders can have a slower onset: for example, the stroke-in-evolution that may or may not be stepwise; the intracerebral haemorrhage that evolves over many minutes; the subdural that develops over hours to days (although here the bleeding results in a mass lesion); or the giant aneurysm that behaves as a tumour with symptoms due to the mass.

• In older patients with a chronic disease the deterioration is so slow that it is assumed that their increasing disability is simply related to old age until there is a sudden crisis, such as a fall where they are unable to get up. Patients present under these circumstances with an apparent illness of sudden onset, where in reality it is simply the ‘straw that broke the camel’s back’ phenomenon. The true nature is only clarified when a careful and detailed history of slowly evolving disability is obtained.

THE NATURE AND DISTRIBUTION OF SYMPTOMS

Symptom clarification

When clarifying the nature of symptoms, the following sample questions may be helpful:

• By weakness, do you mean an actual loss of strength?

• You said you had double vision – do you mean you actually saw two objects and, if you did, were they side-by-side or one above the other?

• When you say you are dizzy, what do you mean? Do you have a feeling of light-headedness or is it a sensation that the room or your head is spinning?

• When you say your speech is slurred, do you mean it sounds as if you are intoxicated (this would be the description of dysarthria) or do you mean that either you have difficulty finding the words that you want to say or, even though you can think of what you want to say, you are unable to actually say those words (this is the description of dysphasia)?

The nature of symptoms

Some symptoms can point to involvement of a specific part of the nervous system, others only indicate a particular pathway or system within the nervous system, while others are so non-specific that they have no value in localising the problem.

SYMPTOMS THAT LOCALISE TO A PARTICULAR PART OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

• Unilateral visual loss indicates that either the ipsilateral eye or optic nerve is affected.2

• Visual loss affecting both temporal fields (lateral vision): optic chiasm.3

• Hemianopia (loss of vision to one side): the optic radiation or occipital cortex.

• Vertical diplopia: brainstem, specifically the midbrain, 3rd or 4th cranial nerve (very rarely due to local muscle; superior and inferior recti or superior and inferior oblique muscle problems in the orbit).

• Horizontal diplopia: brainstem, specifically the pons, 6th cranial nerve or median longitudinal fasciculus (very rarely due to local muscle; medial or lateral rectus problems within the orbit).

• The ‘pill-rolling’ tremor at rest of Parkinson’s: basal ganglia – specifically the subthalamic nucleus.

• Variability of weakness with exercise suggests the neuromuscular junction and myasthenia gravis or Lambert–Eaton syndrome.4 Increased weakness with exercise indicates possible myasthenia gravis, while increased strength (and increased reflexes if examined before and after exercise) with exercise the Lambert–Eaton syndrome.

• A loss of speech is referred to as aphasia, while impairment of speech is referred to as dysphasia affecting the production and/or comprehension of written or spoken language. This almost invariably indicates a dominant hemisphere problem, usually cortical. Very rarely, a subcortical or even a thalamic problem can cause dysphasia.

SYMPTOMS THAT ONLY POINT TO INVOLVEMENT OF A PARTICULAR PATHWAY

• Vertigo (room or head spinning): vestibular system, anywhere from the inner ear through the vestibular nerve to the brainstem and the central vestibular cortex in the temporal lobe

• Weakness: motor pathway between the cerebral cortex and the muscle

• Altered sensation: sensory pathways between the peripheral nerves and the cerebral cortex

• Marked wasting or fasciculations (visible twitching) of muscles: the lower motor neuron from the anterior horn cells in the spinal cord through the anterior nerve roots, brachial or lumbrosacral plexus and peripheral nerves

NON-SPECIFIC SYMPTOMS

• Dysarthria: has no localising value (other than it clearly indicates the problem is above the level of the foramen magnum). It can result from non-dominant hemisphere lesions, deep dominant hemisphere lesions, brainstem pathology and problems affecting the 9th, 10th and 12th nerves, the neuromuscular junction and even disorders of muscle. Neurologists can often differentiate between the different causes of dysarthria but this is difficult for non-neurologists.

• Anosmia: is the loss of the sense of smell; if it is of neurological origin it points to involvement of the olfactory pathway, but in most patients it does not relate to any disorder of the nervous system but is rather due to local nasal pathology.

• Exacerbation of symptoms from heat and exercise: transient worsening of symptoms with heat or exercise that is not relieved by immediate rest is very common with many neurological disorders. One of the most common conditions in which this is a feature is multiple sclerosis.

• Ataxia (or unsteadiness on the legs): is a very non-specific symptom. Although it suggests a cerebellar problem, it can also be present in patients with arthritis in the joints of the legs, weakness or a proprioceptive disturbance in the legs and in patients with vertigo that is vestibular and not cerebellar in origin. A useful question to ask is whether the instability relates to a feeling of instability in the head, indicating probable involvement of the vestibular system, hypotension or a cerebellar problem, or to a sense of unsteadiness in the legs in the absence of any altered sensation in the head, suggesting a problem of weakness or sensory disturbance in the legs.

• Pain: is most often related to non-neurological disorders. If it is of neurological origin, it is almost invariably an indication of involvement of the peripheral nervous system as central pain syndromes are exceedingly rare. Central pain syndromes develop after thalamic infarction in which there is pain in the distribution of the contralateral hemi-sensory loss.

• Urinary or bowel sphincter disturbance: sphincter disturbance is a prominent symptom of intrinsic spinal cord problems (as opposed to extrinsic cord compression in which sphincter disturbance develops late), sacral nerve root lesions or autonomic nervous system involvement. However, in females urinary incontinence is more often of gynaecological origin and not related to a neurological problem.

• Dysphagia: (or difficulty swallowing) can occur with brainstem (medulla) or hemisphere problems and is therefore in itself a poor localising symptom.

The distribution of symptoms

As already discussed in Chapter 1, ‘Clinically oriented neuroanatomy’, ALWAYS think about the underlying neuroanatomy that the nature and distribution of symptoms represents. In most instances the history can assist in establishing whether the pathology is affecting the brain or spinal cord (in the central nervous system) or peripheral nervous system.

As you take the history, think of the nervous system as a map grid with the meridians of longitude and parallels of latitude that were discussed in Chapter 1, ‘Clinically oriented neuroanatomy’. Although the neurological examination is far more important when it comes to accurate localisation, many patients present with transient neurological symptoms and there may not be any neurological signs. For example, establishing from the history that a patient has weakness affecting the entire left side of the body including the face clearly indicates that the problem must be in the central nervous system and on the contralateral side above the mid pons.

PATTERNS OF WEAKNESS

An example of how the pattern of weakness can help to localise the problem while taking a history is shown in Case 2.3.

• Weakness confined to one limb: weakness affecting the entire arm or the entire leg, particularly when it begins suddenly, is most likely to be due to a central rather than a peripheral nervous system problem. The history is not particularly useful when there is a focal weakness in a limb. Focal weakness in a limb can be either of central or peripheral nervous system origin and a neurological examination is needed to sort out the various causes. On the other hand, establishing exactly what part of the limb is weak can narrow down the possibilities if the problem is in the PNS.

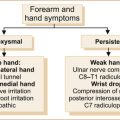

• Weakness of the hand or forearm: C7, C8, T1 nerve root, median, ulnar or radial nerve (Case 2.4 illustrates weakness in the right arm accompanied by some sensory loss.)

• Weakness of the upper arm or shoulder: C5–C6 nerve root, axillary, musculocutaneous or suprascapular nerve problems

• Weakness of the upper leg: L2, L3, L4 nerve root or femoral nerve

• Weakness the lower part of the leg: L5–S1 nerve root, sciatic, common peroneal or posterior tibial nerve problem.

• Hemiparesis: the abrupt onset of weakness of the arm and leg with or without facial involvement is almost certainly a central nervous (upper motor neuron) system problem. Most often it is related to a problem in the contralateral hemisphere, less likely the contralateral brainstem and very rarely in the ipsilateral spinal cord above the level of C5. Slowly evolving hemiparesis could be of central or peripheral nervous system origin.

• Paraparesis: weakness confined to both legs is most often related to a spinal cord problem or a lower motor neuron problem such as a peripheral neuropathy.

• Quadriparesis: four-limb weakness indicates a cervical spinal cord problem above the C5 level, less often a peripheral neuropathy or muscle disease.

PATTERNS OF SENSORY SYMPTOMS

For example, a patient complains of numbness in the hand. If the numbness affects the medial 1½ fingers on both the palmar and dorsal aspects of the fingers and the medial aspect of the hand up to the wrist, this pattern of sensory loss is typical of an ulnar lesion (see Figures 1.14 and 1.15). A second example is the patient who

complains of numbness in the leg, which in itself cannot help localise the problem, whereas numbness confined to the lateral aspect of the thigh below the groin and above the knee is the area supplied by the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh (see Figure 1.20). Case 2.5 illustrates numbness originating from a central nervous system problem.

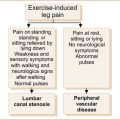

PAIN

When pain does reflect a neurological problem, defining the exact distribution of the pain can be very helpful in localising the problem. Pain radiating from the neck down the arm to the thumb indicates probable involvement of the C6 nerve root. This is often termed referred pain as the site of the pain is not at the site of the pathological process but is referred to another part of the body. Pain confined to one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve on the face indicates involvement of that nerve (although dental pain is also confined to the distribution of the trigeminal nerve as all the dentures are supplied by the nerve), whereas pain beyond the distribution of the trigeminal nerve clearly excludes trigeminal neuralgia (see Chapter 9, ‘Headache and facial pain’). Case 2.6 illustrates how the distribution of pain and reduced sensation can aid in diagnosis.

PAST HISTORY, FAMILY HISTORY AND SOCIAL HISTORY

Another important point is that, although patients may state that there is a past or family history of a particular illness, the diagnosis may have been incorrect. This is another reason why the past and family history should not be used to make a diagnosis. It is very important to be certain that there is either proof of the diagnosis or symptoms that are consistent with that diagnosis. This is particularly so with a past or family history of an illness such as migraine, for which there is no test to confirm the diagnosis. In many instances on detailed questioning the prior headaches do not fulfil the criteria for migraine as defined by the International Headache Society [3]. Many relatives are told that the cause of death was a heart attack when patients suffer sudden death or succumb during sleep without any pathological confirmation of the diagnosis.

In many patients with chronic neurological diseases, there is a tendency for both the patient and the inexperienced practitioner to assume that all new symptoms relate to that chronic neurological illness. However, a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease does not exclude the patient from suffering a stroke, spinal cord compression or some other neurological problem. In a patient with a chronic slowly progressive neurological problem, the vital clue that there may be an additional illness is a sudden change in the rate of progression of the disability. An example of this seen by the author is a patient with slowly progressive difficulty walking over years related to Parkinson’s disease who developed a rapid decline in function from walking to being bedridden within 6 months due to dermatomyositis. Another example is a patient with slowly progressive Parkinson’s disease who develops rapidly worsening walking related to increasing leg weakness due to spinal cord compression.

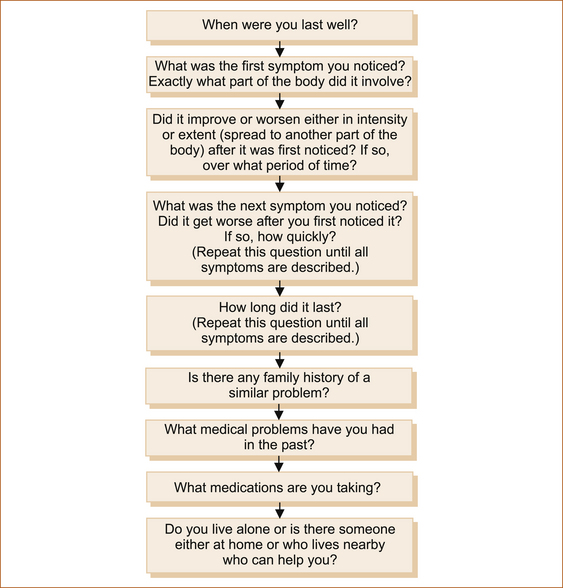

THE PROCESS OF TAKING THE HISTORY

Most often patients come to the consultation with a preconceived idea about what they intend to say, some with many, many pages of notes. After the initial introductions, it is very important to allow the patient time to describe the symptoms without interruption, recording brief comments that you can explore later. If you interrupt the patient at this early stage a vital piece of information may be forgotten while another patient may feel ‘cheated’ and complain that the doctor did not listen to what they had to say! This usually takes a few minutes. In many cases, one has a few clues after the patient’s initial comments but often there is a lot of information that does not help in determining the nature of the problem. At some stage it is necessary to clarify (where possible):

• the mode of onset and progression of the symptoms

• the exact nature and distribution of the symptoms

• the past, family, social and medication history that may influence subsequent management.

This is best achieved by using the approach illustrated in Figure 2.2.

REFERENCES

1. Spencer, J. Learning and teaching in the clinical environment. BMJ. 2003;326(7389):591–594.

2. Sackett, D.L., Haynes, R.B., Tugwell, P. Clinical diagnostic strategies. In: Sackett D.L., Haynes R.B., Tugwell P., eds. Clinical epidemiology: A basic science for clinical medicine. 1st edn. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1985:11.

3. International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders, 2nd edn. Cephalgia 2004; 24:24–37.

1‘Looking for the pony’ comes from a Christmas tale of two brothers, one of whom was an incurable pessimist and the other an incurable optimist. On Christmas day, the pessimist was given a room full of new toys and the optimist a roomful of horse manure. The optimist threw himself into the muck and began burrowing about in it. When his horrified parents extricated him from the excrement and asked why on earth he was thrashing about in it, he joyfully cried, ‘With all this horse manure, there’s got to be a pony in here somewhere!’

2A note of caution: patients can confuse a visual loss to one side of their vision (a hemianopia) with a monocular or unilateral visual loss. For example, when the patient has visual symptoms on the right, they sometimes assume it is in the right eye. It may, however, be in the right visual field. It is important to clarify whether the patient could see all or only one half of an object; it would be helpful if they had covered each eye in assessing their vision, but most patients do not do this.

3Optic chiasm lesions are extremely rare and most patients are not aware of the bilateral visual disturbance.

4Fatigue- and exercise-induced worsening of symptoms is very common in many chronic neurological disorders and does not imply problems at the neuromuscular junction.