4 The neurological examination

Peripheral nervous system

Examination of the peripheral nervous system assumes a stylised approach when adopting the traditional method. This means following a set pattern of: observation and inspection; tone; power; reflexes; sensation; coordination; and gait. This ignores what was stated earlier, namely that the consultation starts long before the patient enters the consultation room.

Before undergoing the formal peripheral assessment it is worth testing for grasp reflexes. This is done by distracting the patient, possibly by engaging in ‘small talk’, and while doing so sliding the hand out, pushing up against the patient’s palm and fingers. Grasp reflex may be as subtle as feeling the fingers of the patient flexing downwards towards the examiner’s sliding fingers. A positive grasp reflex is indicative of contralateral frontal lobe (upper motor neurone) damage. Other frontal lobe signs may include palmar–mental response. This is evoked by applying a noxious stimulus (such as scratching) to the palm of the patient’s hand and observing the movement of the chin (mentalis muscle) on the same side as the scratched hand. This again suggests contralateral frontal lobe damage.

The glabellar tap is elicited by tapping the index finger on the patient’s forehead. It is best achieved by holding the hand above the forehead and tapping the forehead without coming front-on as this movement, equivocal to menace (as described when testing visual fields in Ch 2), may itself evoke a blink response. When testing the glabellar tap the normal response allows up to three blinks. More than three blinks represent a positive response. When testing glabellar tap it is worth reappraising the patient for ptosis, as attention is focused on the eyelids.

Tone

If Parkinson’s disease is considered, then the initial testing of tone by moving the hand up and down at the wrist should be normal early in the disease process. The patient is asked to move their head from side to side, pushing the ear into the shoulder with each turn, at which time the tone increases with ‘cogwheeling’ and ‘lead pipe’ rigidity. This is pathognomic of early Parkinson’s disease.

Power

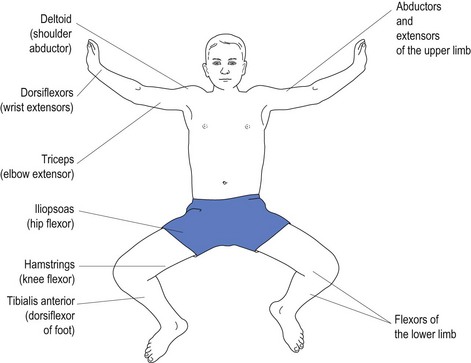

Various conditions affect different muscles. Upper motor neurone weakness, as with stroke, affects the antigravity muscles. Most inexperienced doctors have difficulty remembering which muscles constitute the antigravity muscles (see Fig 4.1).

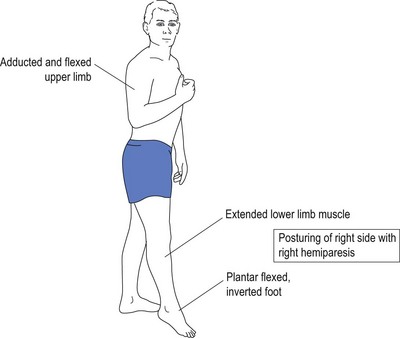

It is because of weakness of the antigravity muscles that the patient with upper motor neurone damage presents with flexion of the upper limbs and extension of the lower limbs. With weakness of the antigravity muscles, the opposing muscles exert their effect causing posturing without counter effect by opposing muscles (see Fig 4.2).

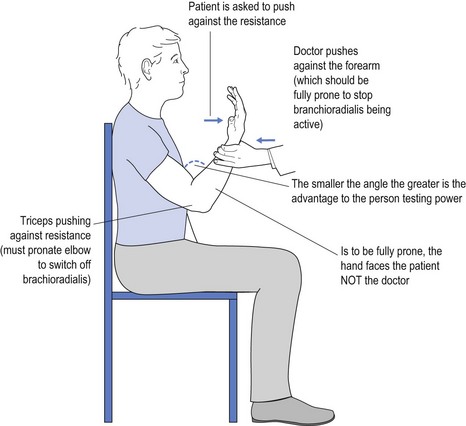

It is obvious that a 60 kg female may have trouble overcoming the strength of a 100 kg male who is engaged in very physical work. One way to overcome this is to use mechanical advantage to test power. An example of this might be to test triceps power by flexing the elbow much more than the traditional 90° (see Fig 4.3).

Power is graded on a five-point scale:

Weakness may be restricted to particular innervated muscles with mononeuritic disease. An example of this is specific weakness of abductor pollicis brevis (APB), flexor pollicis brevis (FPB), opponens pollicis and the lateral two lumbricals with median nerve entrapment and carpal tunnel disease.

Reflexes

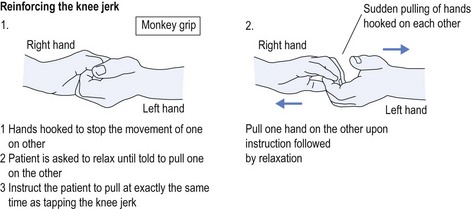

Some anxious patients are too ‘uptight’ to allow the free movement/jerk of the muscle. The patient needs to relax, and the best way to encourage this is to distract the patient. Ask the patient to adopt the finger clasp known as a ‘monkey grip’ (see Fig 4.4). The patient is asked to close the eyes and relax, and to only pull on the grip when told to do so. This instruction is given as the reflex is tapped. Some neurologists ask the patient to clench the teeth at the exact same time as tapping the reflex. This is another method of distraction.

It is more difficult to test upper limb deep tendon reflexes in a patient who is stressed (and uptight) and who is ‘splinting’ their muscles. To test the right upper limb deep tendon reflexes, the patient is given an object to hold in the left hand. The patient is asked to squeeze the object at exactly the same time as the deep tendon is tapped with the hammer, or more correctly just as the swing of the hammer starts. The sides are reversed when testing left upper limb reflexes. Again, clenching the teeth tightly at the same time as swinging the tendon hammer to tap the reflex is an alternative method of distraction. This is often best achieved with the patient’s eyes closed so they cannot anticipate the tap of the hammer.

Deep tendon reflexes represent specific spinal root levels:

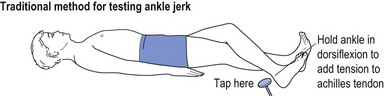

Ankle jerks are difficult to elicit if one is not sure how to do it. If the patient is lying down then the foot is drawn across the opposite shin and the Achilles tendon is tapped (see Fig 4.5).

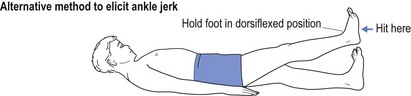

An alternative method is to dorsiflex the ankle joint and then tap the sole of the foot (see Fig 4.6).

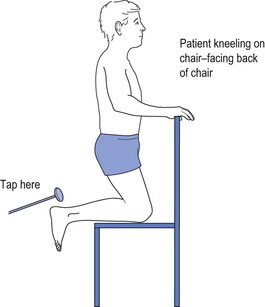

If both these methods fail, then the patient may be asked to kneel on a chair while the Achilles tendon is tapped (see Fig 4.7). This way the patient is distracted by kneeling on the chair and cannot predict when the ankle jerk will be tested, thus reducing the propensity of ‘splinting’.

Sensation

Joint position should be tested moving from the periphery centrally, namely the great toe before the ankle, before the knee, before the hip or, in the upper limb, finger, before the wrist, before the elbow, before the shoulder. The great toe is held between index finger and thumb (held on the sides of the toe rather than the top and bottom). The reason for holding the sides is to avoid additional position sense cues, as may be provided by pushing up and down with pressure on the top or bottom of the toe. A similar approach can be adopted with other joints if the patient cannot identify upward/downward movement of the joint, starting at the periphery, namely great toe or little finger.

Coordination

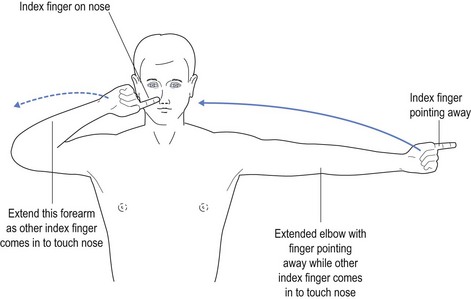

Finger–nose ataxia can easily be tested by asking the patient to place their index finger on their nose while extending the contralateral index finger to the side and swapping the positions repeatedly, seeking exact movements (Fig 4.8).