The myelodysplastic syndromes

Classification

This is not straightforward. The French-American-British (FAB) classification divides MDS into five subtypes depending on morphological features and particularly the number of blood and marrow leukaemic blast cells. The more recent WHO system (Table 25.1) divides MDS into unilineage or multilineage dysplasia, refractory anaemia with ring sideroblasts and dysplasia with excess blasts. The FAB entity chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CMML) is now included in the overlap ‘MDS with myeloproliferative disorder’ category. It is likely that cytogenetic and molecular abnormalities will be increasingly incorporated into the classification; a current example is 5q− syndrome, a distinct subtype of MDS associated with a response to novel therapy and a good prognosis.

Clinical features

The diagnosis may follow a routine blood count in an asymptomatic patient. Where symptoms do occur they range from a mild anaemia to the consequences of severe marrow failure with profound anaemia, leucopenia and thrombocytopenia (Fig 25.1). Abnormal haematopoiesis can cause functional abnormalities of cells, and infection and haemorrhage may be more severe than would be predicted from the degree of cytopenia. Pronounced symptoms are predictably more common in the subtypes with increased blast cells. CMML, like the acute monocytic leukaemias, has specific features including splenomegaly (rare in other forms of MDS), skin infiltration and serous effusions.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of MDS depends on careful morphological examination of the blood film and bone marrow aspirate and trephine specimens (Fig 25.2). Common abnormalities include:

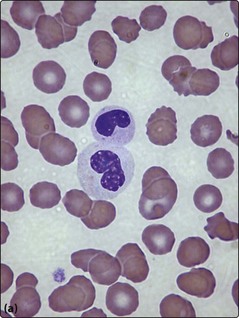

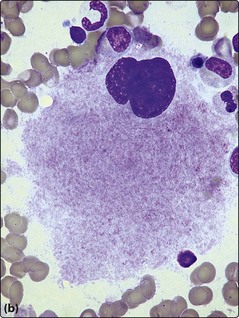

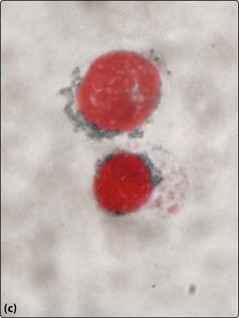

Fig 25.2 Myelodysplastic syndromes.

Morphological changes in the blood film and bone marrow aspirate. (a) Pseudo-Pelger neutrophil with bilobed nucleus. (b) Dysplastic megakaryocyte in the bone marrow. (c) Iron stain of the bone marrow showing ‘ring sideroblasts’.

Peripheral blood. Red cells – anisopoikilocytosis, macrocytosis. Neutrophils – hypogranulation, pseudo-Pelger forms. Platelets – giant forms.

Peripheral blood. Red cells – anisopoikilocytosis, macrocytosis. Neutrophils – hypogranulation, pseudo-Pelger forms. Platelets – giant forms.

Bone marrow. Erythroid cells – multinuclearity, nuclear budding, ring sideroblasts. Myeloid cells – hypogranularity, increased blast cells. Megakaryocytes – giant forms or micromegakaryocytes.

Bone marrow. Erythroid cells – multinuclearity, nuclear budding, ring sideroblasts. Myeloid cells – hypogranularity, increased blast cells. Megakaryocytes – giant forms or micromegakaryocytes.

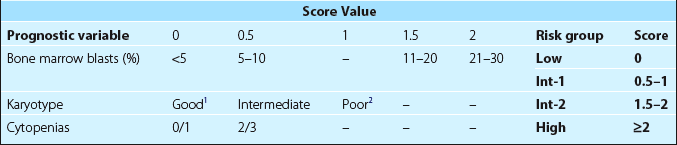

Prognostic factors

The outcome is closely linked to the classification and the risk of transformation to leukaemia. The International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) – based on the number of blood cytopenias, percentage of bone marrow blasts and karyotype – is a simple prognostic tool which can be used to direct treatment (Table 25.2). Median survivals vary from 6 years in the low risk group to less than a year in patients at higher risk. Patients with low risk disease have an average period of 10 years before the onset of AML whereas for high risk patients this is only a few months.

Treatment

Specific treatments

Treatment needs to be individualised according to the type of disease and age of the patient.

High-risk MDS

In high-risk MDS (e.g. RAEB; see Table 25.1), the primary aim is to prolong survival and delay transformation to AML. In younger patients, AML-type chemotherapy and allogeneic stem cell transplantation, the only potentially curative treatment, are possible options. The hypomethylating agent azacitidine has shown efficacy in higher risk subgroups with significantly prolonged survivals and delay of onset of AML. It is given subcutaneously as outpatient therapy and is generally well tolerated.