Chapter 17

The Musculoskeletal System1

The hand of the Lord was upon me … and set me down in the midst of the valley which was full of bones … behold, there were very many in the open valley; and, lo, they were very dry. … Thus saith the Lord God unto these bones: Behold, I will cause breath to enter into you, and ye shall live. And I will lay sinews upon you, and will bring up flesh upon you, and cover with skin, and put breath in you, and ye shall live … there was a noise, and behold a commotion, and the bones came together, bone to bone … and skin covered them … and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood up upon their feet.

Ezekiel 37:1–10

General Considerations

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system rank first among disease conditions that alter the quality of life. This is related to limitation of activity, disability, and impairment. Musculoskeletal disorders are associated with high costs to employers such as absenteeism; lost productivity; and increased health care, disability, and worker’s compensation costs. Musculoskeletal disorders are more severe than the average nonfatal injury or illness (e.g., hearing loss, occupational skin diseases such as dermatitis, eczema, or rash). In the United States, one of every four persons suffers from some sort of musculoskeletal disorder. Here are the facts:

• The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported 372,683 back injury cases involving days away from work.

• Persons who are limited in their work by arthritis are said to have arthritis-attributable work limitations. These limitations affect 1 in 20 working-age adults (aged 18–64) in the United States and 1 in 3 working-age adults with self-reported, doctor-diagnosed arthritis.

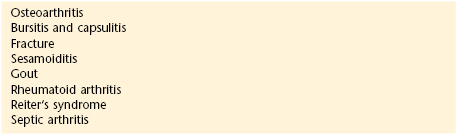

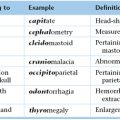

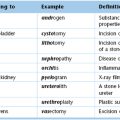

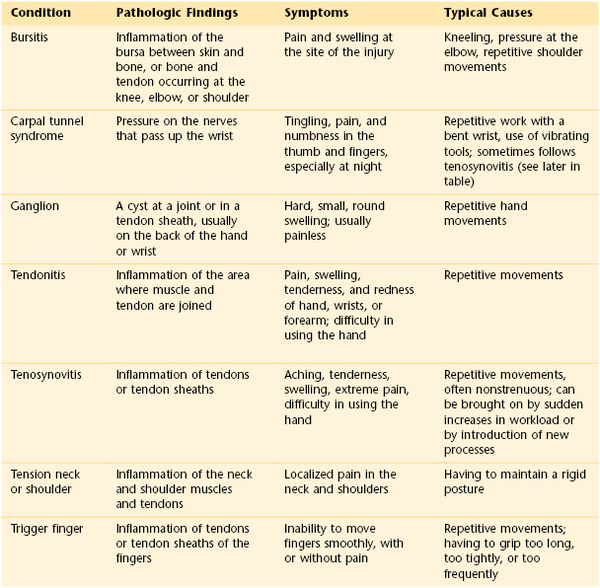

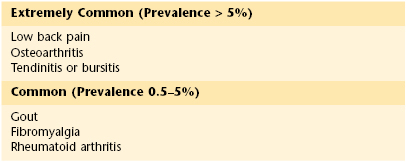

Table 17-1 lists some of the more common musculoskeletal disorders.

Table 17–1

Common Musculoskeletal Disorders

Adapted from http://www.afscme3090.org/ergo/pdf/common_musculoskeletal_disorders.pdf.

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system are divided into two categories: systemic and local. Patients with systemic disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or polymyositis, may appear chronically ill, with generalized weakness, pain, and episodic stiffness of the joints. Patients with local disease are basically healthy individuals who suffer restriction of motion and pain from a single area. Included in this group are patients suffering from back pain, tennis elbow, arthritis, or bursitis. Although these patients may have only local symptoms, their disability can greatly limit their work capacity, and the disease can have a severe effect on their quality of life.

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system rank first in cost to workers’ compensation insurance carriers. Nearly 100,000 workers receive disability payments annually, with a total cost to the carriers of more than $200 billion annually.

Although not usually fatal disorders, musculoskeletal conditions affect the quality of life. Studies indicate that backache is experienced by more than 80% of all Americans at some time in their lives. Patients with backache for longer than 6 months constitute a large portion of permanently disabled individuals. More than 50% of these patients never return to work. More than 25 million Americans suffer from arthritis that necessitates medical attention. Arthritis ranks second to cardiac disease as a cause of limitation of activity. Table 17-2 lists the most common musculoskeletal disorders in adults aged 45 years or older with the disease prevalence in the United States.

Table 17–2

The Most Common Musculoskeletal Disorders in Adults Aged 45 Years and Older:

Prevalence in Adult Populations in the United States

In the United States at least 10% of the population experiences a bone fracture, dislocation, or sprain annually. Each year more than 1.2 million fractures are sustained by women older than 50 years. There are more than 200,000 hip fractures annually, and these are associated with prolonged disability. Osteoporosis2 is the most common musculoskeletal disorder in the world and is second only to arthritis as a leading cause of morbidity in the geriatric population. Postmenopausal osteoporosis and age-related osteoporosis increase the risk of fractures in the older population. There are more than 40 million women in the United States older than 50 years, and more than 50% of them have evidence of spinal osteoporosis. Almost 90% of women older than 75 years have significant radiographic evidence of osteoporosis.

The high prevalence of musculoskeletal disease in older adult patients who require assistance has a significant effect on the American economy. The annual cost of nursing home care for patients with musculoskeletal disease is almost $75 billion. More than 10 million individuals in the United States have some form of inflammatory arthritis, the most prevalent being rheumatoid arthritis. It is estimated that more than 7 million patients have this form of arthritis.

Musculoskeletal problems have the most significant financial effect on the aged population. More than $1 billion is spent annually by Medicare for hospitalization of patients with these conditions. This represents 20% of all Medicare payments.

Structure and Physiology

The principal functions of the musculoskeletal system are to support and protect the body and to bring about movement of the extremities for locomotion and the performance of tasks.

Bone is composed of an organic matrix that consists of collagen fibers embedded in a cementing gel made up of calcium and phosphate. Bone is an actively changing tissue constantly undergoing remodeling while reappropriating its mineral stores and matrix according to mechanical stresses. Normal bone is composed of collagen fibers aligned parallel to the tension stresses to which the bone is exposed. The long bones in adults are composed of tubes of cortical, or compact, bone surrounding a medullary cavity of cancellous, or spongy, bone. Cortical bone exists in areas where support is necessary, whereas cancellous bone is found in areas where hematopoiesis and bone formation occur. In cortical bone, the bone cells, or osteocytes, are enclosed in lacunae, which are spaces in the sheets of bone tissue called lamellae. Several lamellae are arranged concentrically around a vascular channel and are termed a haversian canal. In cancellous bone, the lamellae are not arranged in haversian systems but are organized into a spongy network called trabeculae. These trabeculae align along lines of stress.

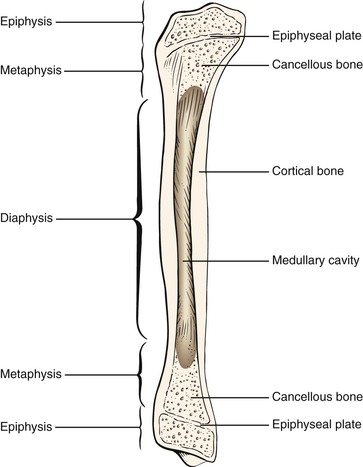

The ends of the long bones, called epiphyses, are expanded near the articular surfaces and are composed of spongy bone. The shaft of the long bone, the diaphysis, is covered with a layer of periosteum. The inner cavity of the long bone is lined with endosteum and is filled with marrow.

For a time, a layer of cartilage exists between the diaphysis and the epiphysis. This cartilage is known as the growth plate or epiphyseal plate. The purpose of the growth plate is to determine the longitudinal growth of the bone. The parts of a long bone are illustrated in Figure 17-1.

Figure 17–1 Anatomy of a long bone.

Cells in the periosteum can develop into osteoblasts, which lay down new bone, or into osteoclasts, which resorb bone. Trauma, infection, and tumors stimulate the development of osteoblasts. Osteoblasts secrete the matrix that is refashioned into lamellae and arranged to endure the mechanical stresses to which the bone is subjected.

Skeletal muscle is an organ, the contraction of which produces movement.

Ligaments attach bone to bone, and tendons attach muscle to bone. Both are dense connective tissues that offer great resistance to pulling forces.

Cartilage is a type of connective tissue with great resilience. It plays an important role in joint function and in determining bone length.

The basic functional unit of the musculoskeletal system is the joint. A joint is a union of two or more bones. There are several types of joints in the body:

Immovable joints are fixed as a result of fibrous tissue banding. Examples of this type of joint are the sutures of the skull. Slightly movable joints are termed symphyses. In this type of joint, fibrocartilage joins the articulating bones. The pubic symphysis is an example of a slightly movable joint. The most common type of joint is the movable joint. The body has many different types of movable joints, also known as synovial joints. In synovial joints, the bone structures come in contact with each other and are covered with hyaline articular cartilage. A capsule surrounds the joint by attaching to the bones on either side of the joint. Within the capsule is a small amount of synovial fluid, which plays a role in joint lubrication and nourishment of the articular cartilage. Synovial joints are classified according to the type of movement their structure permits. The classifications are as follows:

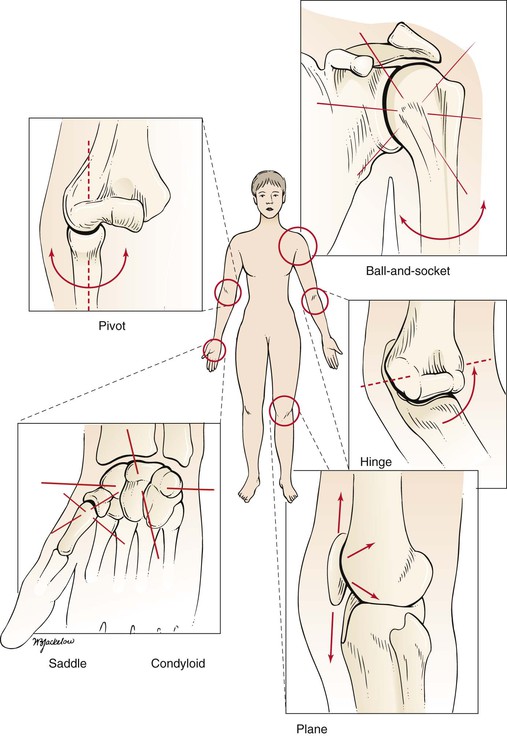

A hinge joint permits movement in only one axis: namely, flexion or extension. The axis is transverse. An example of a hinge joint is the elbow. A pivot joint permits rotation in one axis. The axis is longitudinal along the shaft of the bone. One bone moves around a central axis without any displacement from that axis. An example of a pivot joint is the proximal radioulnar joint. A condyloid joint permits movement in two axes. The articular surfaces are oval; thus these joints have been described as “egg-in-spoon” joints. One axis is the long diameter of the oval, and the other axis is the short diameter of the oval. The wrist joint is an example of a condyloid joint. A saddle joint is also a biaxial joint. The articular surfaces are saddle-shaped, with movements similar to those of a condyloid joint. The carpometacarpal joint of the thumb is an example of a saddle joint. The ball-and-socket joint is an example of a polyaxial joint; motion is possible in many axes. In a ball-and-socket joint, the articular surfaces are reciprocal segments of a sphere. The hip and shoulder joints are examples of ball-and-socket joints. A plane joint is also a polyaxial joint. In the plane joint, the articular surfaces are flat, and one bone merely rides over the other in many directions. The patellofemoral joint is an example of a plane joint. These different types of movable joints are shown in Figure 17-2.

Figure 17–2 Types of movable joints.

The stability of a joint depends on the following:

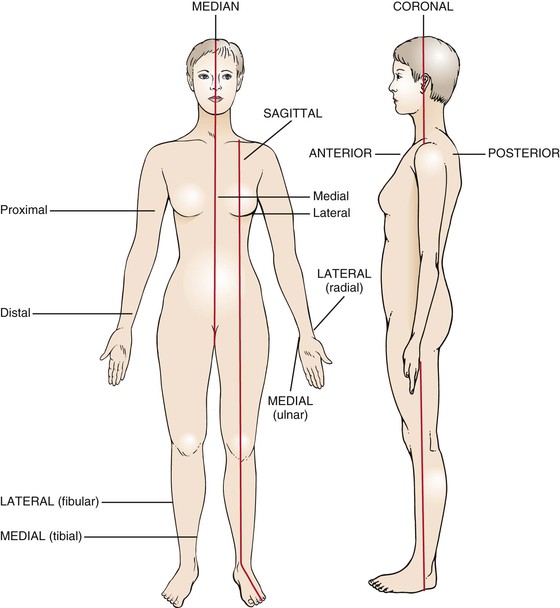

It is necessary to be familiar with certain anatomic terms that refer to position (Table 17-3). The median plane bisects the body into right and left halves. A plane parallel to the median plane is a sagittal plane. The terms medial and lateral are used in reference to the sagittal plane. A position closer to the median plane is medial; farther from the median plane, it is lateral. In the upper limb, the term ulnar is often used to denote medial, and radial to denote lateral. In the lower limb, tibial is used to denote medial, and peroneal or fibular denotes lateral. These anatomic terms are illustrated in Figure 17-3.

Table 17–3

Anatomic Terms for the Upper and Lower Limb

| Limb | Medial | Lateral |

| Upper | Ulnar | Radial |

| Lower | Tibial | Peroneal fibular |

Figure 17–3 Anatomic terms.

The front of the body is the anterior, or ventral, surface, and the back of the body is the posterior, or dorsal, side. The palmar, or volar, aspect of the hand is the anterior surface. The dorsal aspect of the foot faces upward, and the plantar aspect is the sole. Proximal refers to the part of an extremity that is closest to its root; distal refers to the part farthest from the root.

The most important terms relating to deformities of the bone structure are valgus and varus. In a valgus deformity, the distal portion of the bone is displaced away from the midline, and angulation is toward the midline. In a varus deformity, the distal portion of the extremity is displaced toward the midline, and angulation is away from the midline. The name of the deformity is determined by the joint involved. A valgus deformity of the knees, knock-knee, is termed genu valgum. A varus deformity of the knee, bowleg, is termed genu varum.

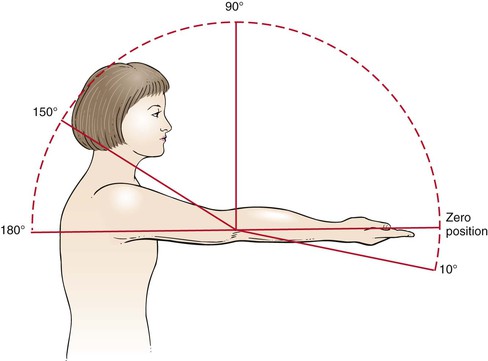

In the evaluation of a joint, assess the range of motion. Each joint has a characteristic range of motion that can be measured passively and actively. Passive range of motion is the motion elicited when the examiner moves the patient’s body. Active range of motion is the motion the patient performs as a result of moving the musculature. The passive range of motion usually equals the active range of motion except in cases of paralyzed muscles or ruptured tendons. The range of motion of individual joints is discussed later in this chapter. Joint motion is measured in degrees of a circle, with the joint at the center. If a limb is extended with the bones in a straight line, the joint is at zero position. The zero position is the neutral position of the joint. As the joint is flexed, the angle increases. The concept of range of motion is illustrated in Figure 17-4.

Figure 17–4 Range of motion.

The six basic types of joint motion are as follows:

The definitions of these motions and the joints at which they occur are summarized in Table 17-4.

Table 17–4

Joint Motion

| Motion | Definition | Example |

| Flexion | Motion away from the zero position | Most joints |

| Extension | Return motion to the position* | Most joints |

| Dorsiflexion | Movement in the direction of the dorsal surface | Ankle, toes, wrist, fingers |

| Plantar (or palmar) flexion | Movement in the direction of the plantar (or palmar) surface | Ankle, toes, wrist, fingers |

| Adduction | Movement toward the midline† | Shoulder, hip, metacarpophalangeal, metatarsophalangeal joints |

| Abduction | Movement away from the midline | Shoulder, hip, metacarpophalangeal, metatarsophalangeal joints |

| Inversion | Turning of the plantar surface of the foot inward | Subtalar and midtarsal joints of the foot |

| Eversion | Turning of the plantar surface of the foot outward | Subtalar and midtarsal joints of the foot |

| Internal rotation | Turning of the anterior surface of a limb inward | Shoulder, hip |

| External rotation | Turning of the anterior surface of a limb outward | Shoulder, hip |

| Pronation | Rotation so that the palmar surface of the hand is directed downward | Elbow, wrist |

| Supination | Rotation so that the palmar surface of the hand is directed upward | Elbow, wrist |

* Extension that goes beyond the zero position is called hyperextension.

† In the hand or foot, the midline is an imaginary line through the middle finger or middle toe, respectively.

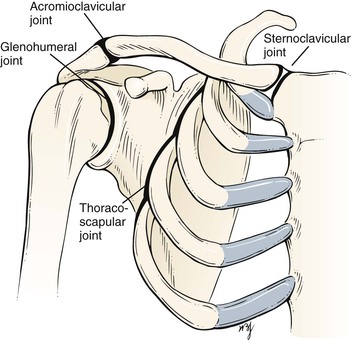

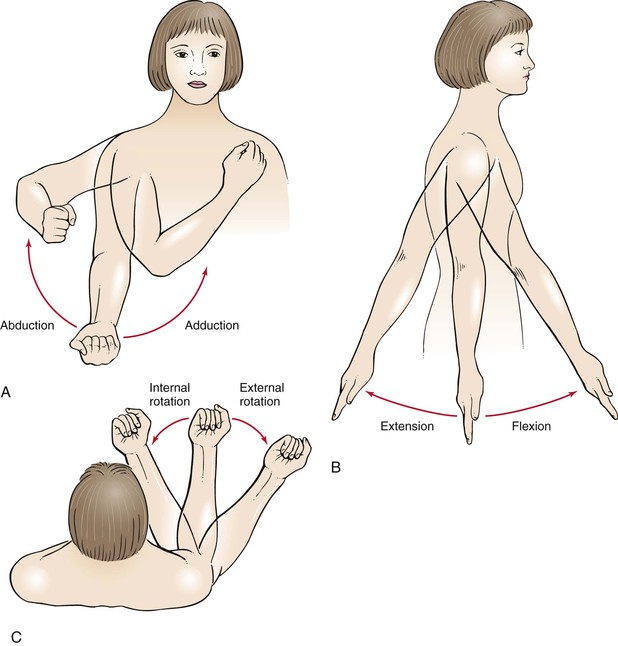

The anatomy of the shoulder joint is illustrated in Figure 17-5. The joint movements at the shoulder are abduction and adduction, flexion and extension, and internal and external rotation. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-6.

Figure 17–5 Anatomy of the shoulder joint.

Figure 17–6 Range of motion at the shoulder. A, Abduction and adduction. B, Flexion and extension. C, Internal and external rotation.

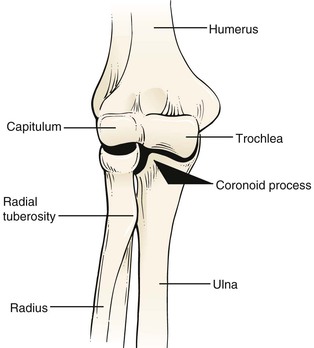

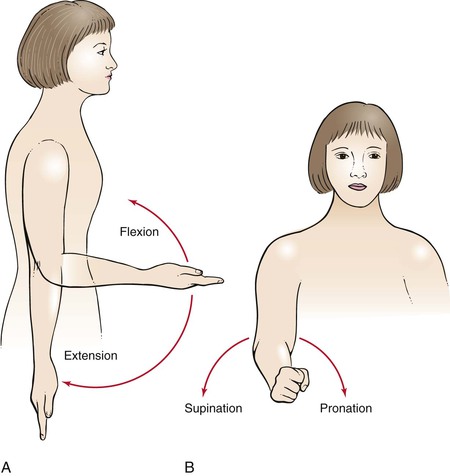

The anatomy of the elbow joint is shown in Figure 17-7. The joint movements at the elbow are flexion and extension and supination and pronation. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-8.

Figure 17–7 Anatomy of the elbow joint.

Figure 17–8 Range of motion at the elbow joint. A, Flexion and extension. B, Supination and pronation.

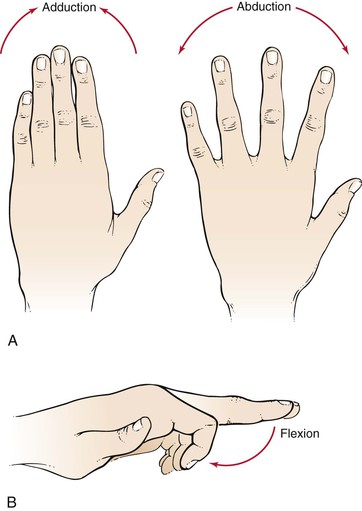

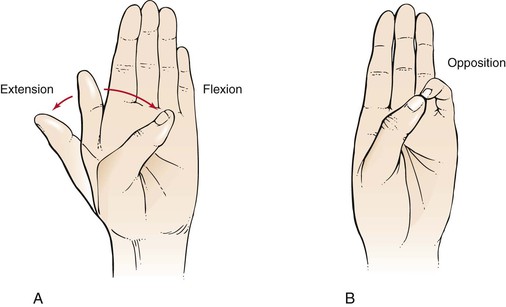

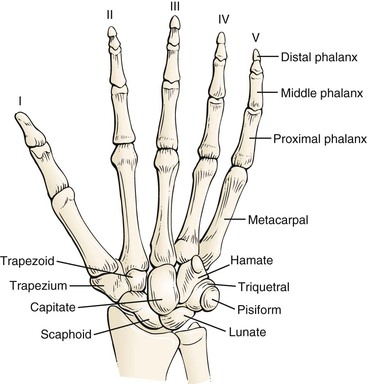

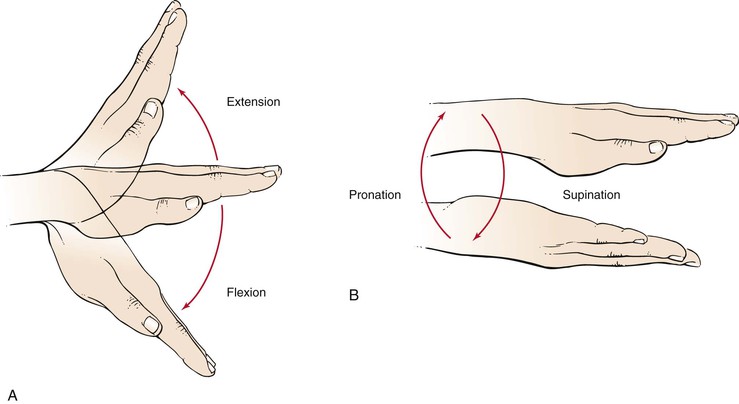

The anatomy of the wrist and fingers is illustrated in Figure 17-9. The joint movements at the wrist are dorsiflexion (or extension) and palmar flexion and supination and pronation. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-10. The joint movements at the fingers are abduction and adduction and flexion. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-11. The joint movements of the thumb are flexion and extension and opposition. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-12.

Figure 17–9 Anatomy of the wrist and fingers.

Figure 17–10 Range of motion at the wrist joint. A, Dorsiflexion (extension) and palmar flexion. B, Supination and pronation.

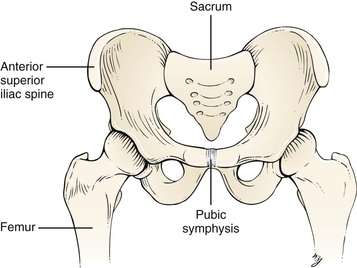

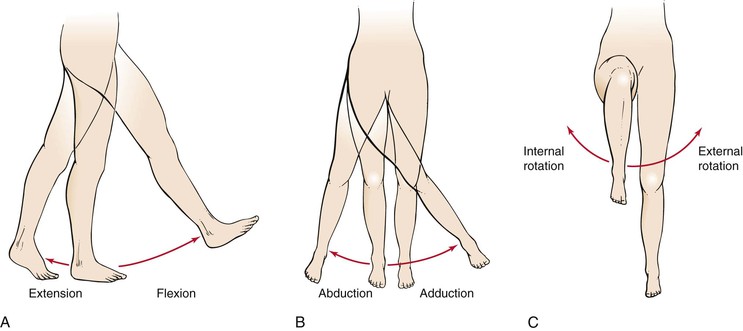

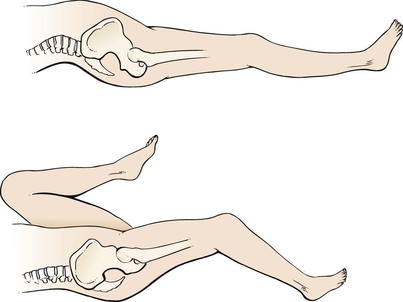

The anatomy of the hip is illustrated in Figure 17-13. The joint movements at the hip are flexion and extension, abduction and adduction, and internal and external rotation. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-14.

Figure 17–13 Anatomy of the hip joint.

Figure 17–14 Range of motion at the hip joint. A, Flexion and extension. B, Abduction and adduction. C, Internal and external rotation.

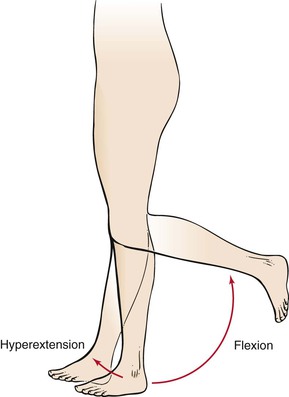

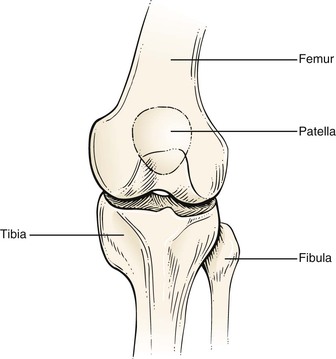

The anatomy of the knee is shown in Figure 17-15. The joint movements at the knee are flexion and hyperextension. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-16.

Figure 17–15 Anatomy of the knee joint.

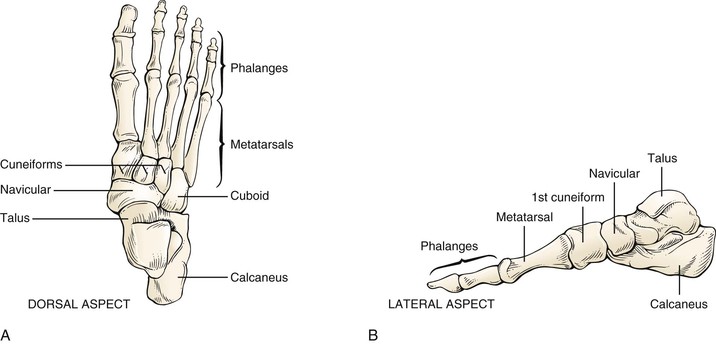

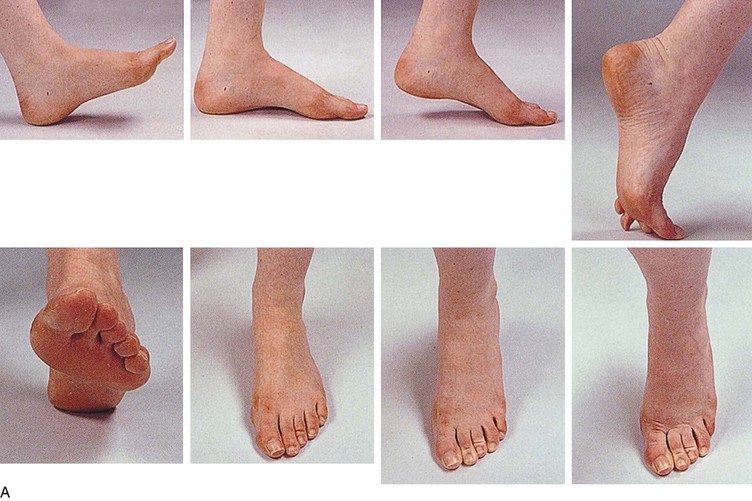

The anatomy of the ankle and foot is illustrated in Figure 17-17. There are 26 bones and 55 articulations in the foot. The bones can be divided into three regions: forefoot, midfoot, and rear foot. The forefoot is represented by the 14 bones of the toes and 5 metatarsals. The big toe (hallux) has two phalanges, two joints (interphalangeal [IP] joints), and two tiny, round sesamoid bones that enable it to move up and down. The sesamoid bones are about the size of a kernel of corn. These bones are embedded in the flexor hallucis brevis tendon, one of several tendons that exert pressure from the big toe against the ground and help initiate the act of walking: the propulsive phase of the gait cycle. The other four toes each have three bones and two joints. The phalanges are connected to the metatarsals by five metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints at the ball of the foot. The forefoot bears half the body’s weight and balances pressure on the ball of the foot.

The midfoot consists of the three cuneiform bones, the cuboid, and the navicular. The midfoot has five irregularly shaped tarsal bones, forms the foot’s arch, and serves as a shock absorber. The bones of the midfoot are connected to the forefoot and the hindfoot by muscles and the plantar fascia (arch ligament).

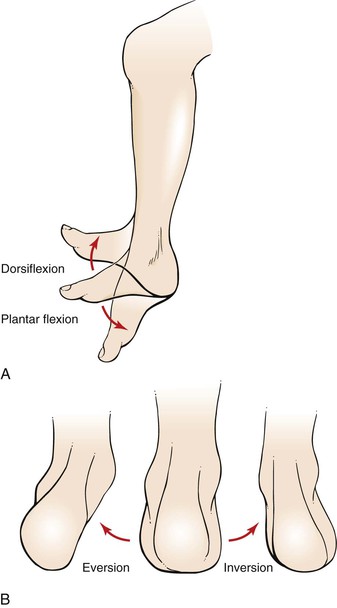

The rear foot is composed of the talus and the calcaneus. The foot contains two arches: the longitudinal in the midpart and the transverse in the forepart. The midtarsal joint is formed by the articulations of the navicular to the talus and the calcaneus to the cuboid. The largest tarsal bone is the calcaneus, the bottom of which is cushioned by a layer of fat. The attachment of the foot to the leg occurs through the talus. The joint movements at the ankle are dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. The motion of the subtalar joint is inversion and eversion. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-18.

Figure 17–18 Range of motion at the ankle and foot joints. A, Dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. B, Eversion and inversion.

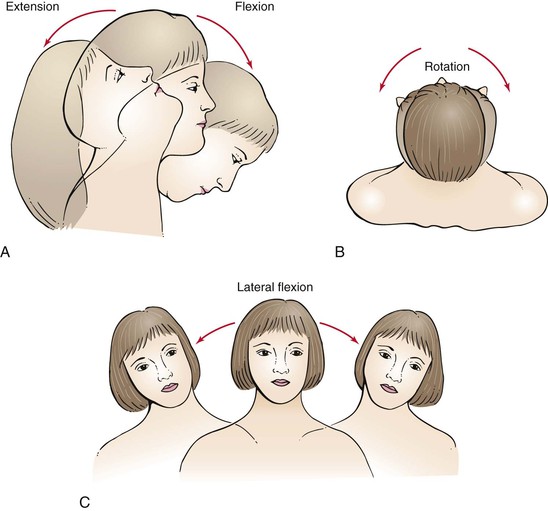

The anatomy of the cervical spine is shown in Figure 17-19. The joint movements of the neck are flexion and extension, rotation, and lateral flexion. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-20.

Figure 17–19 Anatomy of the cervical spine.

Figure 17–20 Range of motion at the cervical spine. A, Flexion and extension. B, Rotation. C, Lateral flexion.

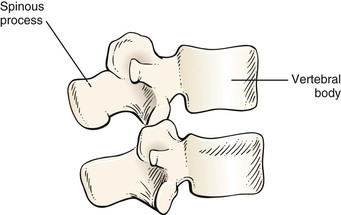

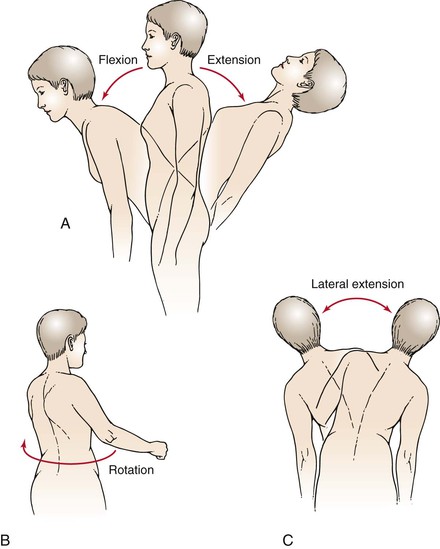

The anatomy of the lumbar spine is illustrated in Figure 17-21. The joint movements of the lumbar spine are flexion and extension, rotation, and lateral extension. These motions are illustrated in Figure 17-22.

Figure 17–21 Anatomy of the lumbar spine.

Figure 17–22 Range of motion at the lumbar spine. A, Flexion and extension. B, Rotation. C, Lateral extension.

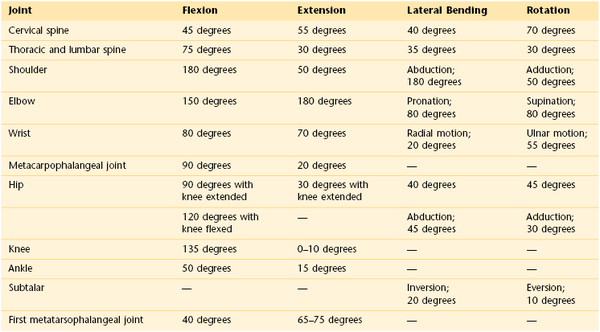

A summary of normal joint ranges of motion is shown in Table 17-5.

Review of Specific Symptoms

The most common symptoms of musculoskeletal disease are as follows:

The location, character, and onset of each of these symptoms must be ascertained. It is important for the interviewer to determine the time course of any of these symptoms.

Pain

Pain can result from disorders of the bone, muscle, or joint. Ask the following questions:

“When did you first become aware of the pain?”

“Where do you feel the pain? Point to the most painful spot with one finger.”

“Did the pain occur suddenly?”

“During which part of the 24-hour day is your pain worse: Morning? Afternoon? Evening?”

“Did a recent illness precede the pain?”

“What do you do to relieve the pain?”

“Is the pain relieved by rest?”

“What kinds of medications have you taken to relieve the pain?”

“Have you noticed that the pain changes according to the weather?”

“Do you have any difficulty putting on your shoes or coat?”

“Does the pain ever awaken you from sleep?”

“Does the pain shoot to another part of your body?”

“Have you noticed that the pain moves from one joint to another?”

“Has there been any injury, overuse, or strain?”

“Have you noticed any swelling?”

Bone pain may occur with or without trauma. It is typically described as “deep,” “dull,” “boring,” or “intense.” The pain may be so intense that the patient is unable to sleep. Typically, bone pain is not related to movement unless a fracture is present. Pain from a fractured bone is often described as “sharp.” Muscle pain is frequently described as “crampy.” It may last only briefly or for longer periods. Muscle pain in the lower extremity on walking, described in Chapter 12, The Peripheral Vascular System, is suggestive of ischemia of the calf or hip muscles. Muscle pain associated with weakness is suspect for a primary muscular disorder. Joint pain is felt around or in the joint. In some conditions, the joint may be exquisitely tender. Movement usually worsens the pain, except with rheumatoid arthritis, in which movement often reduces the pain. Pain of several years’ duration rules out an acute septic process and usually malignancy. Chronic infection with tuberculosis or fungal infections may smolder for years before pain is present. The severity of the pain can often be assessed by determining the interval between the pain’s onset and the patient’s seeking medical attention.

The time of day when the pain is worse may be helpful in diagnosing the disorder. The pain of many rheumatic disorders tends to be accentuated in the morning, particularly on rising. Tendinitis worsens during the early morning hours and eases by midday. Osteoarthritis worsens as the day progresses.

Sudden onset of pain in a MTP joint should raise suspicion of gout. Entrapment syndromes are apt to radiate pain distally. Severe pain may awaken the patient from sleep. Rheumatoid arthritis and tendinitis often cause early awakening because of pain, particularly when the patient is lying on the affected limb.

Acute rheumatic fever, leukemia, gonococcal arthritis, sarcoidosis, and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis are commonly associated with migratory polyarthritis, in which one joint is affected, the disease subsides, and then another joint becomes involved.

Viral illnesses are commonly associated with muscle aches and pains. A recent history of a sore throat, with joint pain occurring 10 to 14 days later, is suspect for rheumatic fever. If rest does not relieve the pain, serious musculoskeletal disease may be present. The interviewer should keep in mind the possibility of referred pain. Pain from a hip disorder is frequently referred to the knee, especially in a child.

Weakness

Muscular weakness should always be differentiated from fatigue. Ascertain which functions the patient is unable to perform as a result of “weakness.” Is the weakness related to proximal or distal muscle groups? Proximal weakness is usually a myopathy; distal weakness is usually a neuropathy. A patient with the symptom of muscular weakness should be asked these questions:

“Do you have difficulty combing your hair?”

“Do you have difficulty lifting objects?”

“Have you noticed any problem with holding a pen or pencil?”

“Do you have difficulty turning doorknobs?”

“Do you have trouble standing up after sitting in a chair?”

“Have you noticed any decrease in your muscle size?”

“Do you have trouble with double vision? Swallowing? Chewing?”

A patient with proximal weakness of the lower extremity has difficulty walking and crossing the knees. A proximal weakness of the upper extremity is manifested by difficulty brushing the hair or lifting objects. Patients with polymyalgia rheumatica have proximal muscle weakness. This condition is discussed in Chapter 22, The Geriatric Patient. A distal weakness of the upper extremity is manifested by difficulty turning doorknobs or buttoning a shirt or blouse. Patients with myasthenia gravis have generalized weakness, diplopia, and difficulty swallowing and chewing.

Deformity

Deformity may be the result of a congenital malformation or an acquired condition. In any patient with a deformity, it is important to determine the following:

Limitation of Motion

Limitation of motion may result from changes in the articular cartilage, scarring of the joint capsule, or muscle contractures. Determine the types of motion the patient can no longer perform easily, such as combing the hair, putting on shoes, or buttoning a shirt or blouse.

Stiffness

Stiffness is a common symptom of musculoskeletal disease. For example, a patient with arthritis of the hip may have difficulty crossing his or her legs to tie shoes. Ask the patient whether the stiffness is worse at any particular time of day. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis tend to experience stiffness after periods of joint rest. These patients typically describe morning stiffness, which may take several hours to subside.

Joint Clicking

Joint clicking is commonly associated with specific movements in the presence of dislocation of the humerus, displacement of the biceps tendon from its groove, degenerative joint disease, damaged knee meniscus, and temporomandibular joint problems.

Effect of Musculoskeletal Disease on the Patient

Musculoskeletal diseases have an enormous influence on the lives of patients and their families. The perturbation of a patient’s personal life and restriction of activities as a result of disability are frequently more catastrophic than the muscle or joint pain itself.

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system range from minor aches and pains to severe crippling disorders, often associated with premature death. Rheumatoid arthritis is a crippling disorder that strikes many patients in the prime of life. In addition to having joint pain and reduced activity, patients with rheumatoid arthritis fear the possibility of being crippled. They become more dependent on others as the disease progresses. The disability alters patients’ self-image and self-esteem. The altered body image may be devastating; patients often become withdrawn.

The physical limitations of musculoskeletal disease, especially when accompanied by joint or muscle pain, threaten patients’ integrity in their social world. Marital and familial ties may suffer as patients become more debilitated and withdrawn. Because of their disability, patients may have to change occupations, which causes further anxiety and depression. The loss of status and financial adjustments may jeopardize the marital situation. The fear of losing independence is extremely common. Patients are forced to make more demands on others but recognize that this may only worsen their relationships.

Rehabilitation is important for the physical and psychological improvement of the patient. The patient is the key contributor to this rehabilitative process. Initially, motivation may be provided by people caring for the patient, but it is the patient’s own attitude that determines whether the rehabilitation will be successful. The patient’s motivation to tackle the disability depends on many factors, including self-image, as well as psychological, social, and financial resources. It is important for the clinician to gain the patient’s confidence to help him or her overcome the disability.

Physical Examination

No special equipment is necessary for the examination of the musculoskeletal system.

The purpose of the internist’s musculoskeletal examination is as a screening examination to indicate or exclude functional impairment of the musculoskeletal system. The examination should take only a few minutes and should be part of the routine examination of all patients. If an abnormality is noted or if the patient has specific symptoms referable to a particular joint, a more detailed examination of that area is indicated. Detailed descriptions of the examination of specific joints follow the discussion of the screening examination.

Screening Examination

In the screening examination, the clinician should pay particular attention to the following:

General Principles

During inspection, asymmetry should be assessed. Nodules, wasting, masses, or deformities may be responsible for the absence of symmetry. Are there any signs of inflammation? Swelling, warmth, redness, and tenderness are suggestive of inflammation. To determine a difference in temperature, use the back of your hand to compare one side with the other.

Palpation may reveal areas of tenderness or discontinuity of a bone. Is crepitus present? Crepitus is a palpable crunching sensation often felt in the presence of roughened articular cartilages.

The assessment of range of motion of specific joints is next. Keep in mind that inflamed or arthritic joints may be painful. Move these joints slowly.

Muscle strength and integrated function are usually evaluated during the neurologic examination, and these topics are discussed in Chapter 18, The Nervous System.

Evaluate Gait

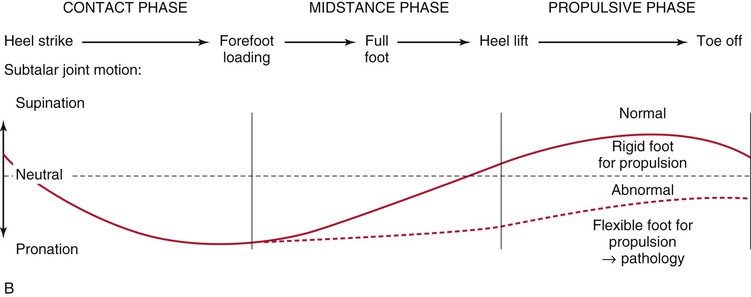

The first part of the screening examination consists of inspection of gait and posture. To determine any eccentricity of gait, ask the patient to disrobe down to underwear and walk barefoot. Have the patient walk away from you, then back to you on tiptoes, away from you on the heels, and finally back to you in tandem gait. If there is any gait difficulty, these maneuvers must be modified. The positions of the foot during the normal gait cycle are shown in Figure 17-23.

Observe the rate, rhythm, and arm motion used in walking. Does the patient have a staggering gait? Are the feet lifted high and slapped downward firmly? Does the patient walk with an extended leg that is swung laterally during walking? Are the steps short and shuffling? A complete discussion of gait abnormalities can be found in Chapter 18, The Nervous System. Figure 18-60 illustrates common gait abnormalities.

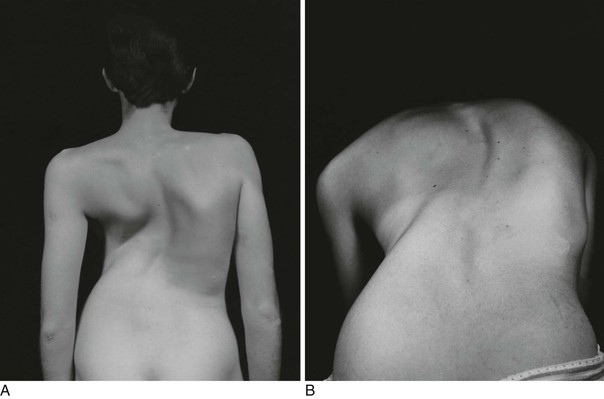

Evaluate the Spine

Attention should then focus on the spine to detect any abnormal spinal curvatures. Have the patient stand erect, and stand at the patient’s side to inspect the profile of the patient’s spine. Are the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar curves normal?

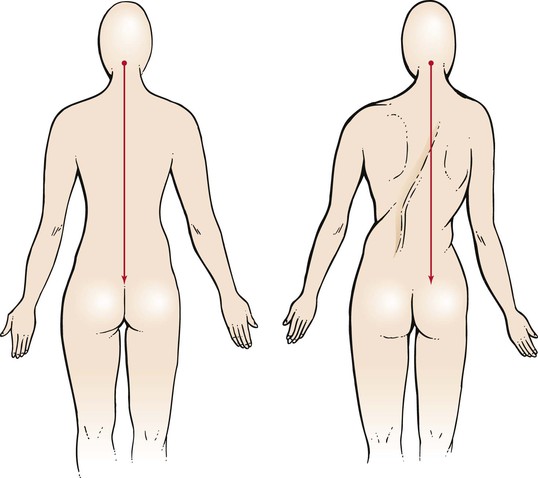

Move to inspect the patient’s back. What is the level of the iliac crests? A difference may result from a leg length inequality, scoliosis, or flexion deformity of the hip. An imaginary line extending from the posterior occipital tuberosity should run over the intergluteal cleft. Any lateral curvature is abnormal. Figure 17-24 illustrates this point. Figure 17-25A shows severe kyphoscoliosis. See also Figure 10-6.

Figure 17–24 Technique for evaluating “straightness” of the spine. Lateral deviation of the spine may be related to a herniated disc or to spasm of the paravertebral muscles. This functional deviation is often termed a list. True scoliosis may result from an actual deformity of the spine. In many cases, the spine twists in the opposite direction, so that a plumb line may actually be in the center.

Ask the patient to bend forward, flexing at the trunk as far as possible with the knees extended. Note the smoothness of this action. This position is best for determining whether scoliosis is present. As the patient bends forward, the lumbar concavity should flatten. Figure 17-25B shows the patient in Figure 17-25A when bending forward. A persistence of the concavity may indicate an arthritic condition of the spine called ankylosing spondylitis.

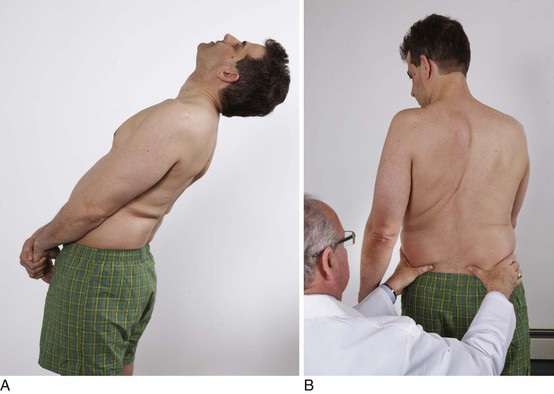

Ask the patient to bend to each side from the waist and then bend backward from the waist to test extension of the spine, as shown in Figure 17-26A.

Figure 17–26 Technique for evaluating motion of the lumbar spine. A, Test for extension of the spine. B, Test for rotation of the spine.

To test rotation of the lumbar spine, sit on a stool behind the patient and stabilize the patient’s hips by placing your hands on them. Ask the patient to rotate the shoulders one way and then reverse, as shown in Figure 17-26B.

Evaluate Strength of the Lower Extremities

To assess the function of all major joints of the lower extremities, stand in front of the patient. Have the patient squat, with knees and hips fully flexed. Assist the patient by holding his or her hands to secure balance. This is shown in Figure 17-27. Ask the patient to stand. Observing the manner in which the patient squats and then stands provides an excellent impression of the muscle strength and joint action of the lower extremities.

In addition, assessment of specific muscle groups can be performed and integrated into the arthrometric examination. Muscle strength can be graded according to the scale described in Chapter 18, The Nervous System.

Measure the dorsiflexors and plantar flexors. With the patient seated, have the patient dorsiflex and plantarflex the foot against resistance. This can also be accomplished by asking the patient to walk toward and away from you on the heels and then on the toes. Injury to the common peroneal nerve causes weakness of the anterior muscle group, with a diminished capacity to dorsiflex the foot. Injury to the Achilles tendon or to the gastrosoleus complex impairs plantar flexion.

Measure invertors and evertors. With the patient seated, have the patient invert and then evert the foot against resistance.

Measure hip abductors and adductors. With the patient seated, have the patient bring his or her knees together, then apart against the examiner’s opposing force.

Measure the hip flexors and extensors. With the patient seated, have the patient raise the knee off the examination table against the examiner’s downward, then upward, opposing force. Hip extensors can also be assessed by asking the patient to rise from a seated position unassisted.

Human immunodeficiency virus–related myopathy affects proximal muscle groups first, and patients may initially complain of difficulty rising from a chair or climbing stairs.

Evaluate Neck Flexion

The patient is instructed to sit, and the range of motion of the neck is assessed. The patient is asked to put his or her chin on the chest, with the mouth closed, as shown in Figure 17-28. This tests full flexion of the neck.

Figure 17–28 Technique for testing flexion of the neck.

Evaluate Neck Extension

To test full extension of the neck, place your hand between the patient’s occiput and spinous processes of C7. Instruct the patient to trap your hand by extending the neck. This is shown in Figure 17-29.

Figure 17–29 Technique for testing extension of the neck.

Evaluate Neck Rotation

Evaluate rotation of the neck by asking the patient to rotate the neck to one side and touch chin to shoulder. This is shown in Figure 17-30. The examination is then repeated on the other side.

Figure 17–30 Technique for testing rotation of the neck.

Evaluate Intrinsic Muscles of the Hand

The patient is instructed to stretch out the arms, with the fingers spread. The examiner attempts to compress the fingers together against resistance, as shown in Figure 17-31. This tests the intrinsic muscles of the hands.

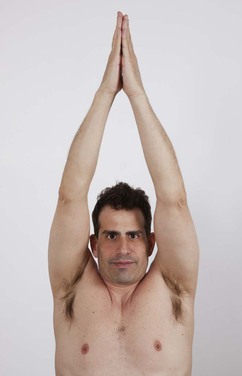

Evaluate External Rotation of the Arm

To test the functional range of rotation of the humerus and the shoulder, acromioclavicular, and sternoclavicular joints, instruct the patient to abduct the arms fully and place the palms together above the head. The arms should touch the patient’s ears with the head and cervical spine in the vertical position. This is shown in Figure 17-32.

Figure 17–32 Technique for testing external rotation of the arm.

Evaluate Internal Rotation of the Arm

The patient is then asked to place his or her hands on the back between the scapulae. The hands should normally reach the level of the inferior angle of the scapulae. This is shown in Figure 17-33. This maneuver tests internal rotation of the humerus and range of motion at the elbow.

Figure 17–33 Technique for testing internal rotation of the arm.

Evaluate Strength of the Upper Extremities

The final test of the screening examination assesses the power of the major groups of muscles in the upper extremities. The patient is asked to grasp the examiner’s index and middle fingers in each hand. The patient is instructed to resist upward, downward, lateral, and medial movement by the examiner. This position is shown in Figure 17-34.

This completes the basic musculoskeletal screening examination. The remainder of this section describes the symptoms and examination of specific joints.

Examination of Specific Joints

Any area must be inspected for evidence of swelling, atrophy, redness, and deformity, as well as palpated for swelling, muscle spasm, and local painful areas. The range of motion is assessed both actively and passively.

Temporomandibular Joint

Symptoms

A patient with temporomandibular joint problems may complain of unilateral or bilateral jaw pain. The pain is worse in the morning and after chewing or eating. The patient may also complain of “clicking” of the jaw.

Examination

To examine this joint, the examiner places his or her index fingers in front of the tragus and instructs the patient to open and close the jaw slowly. The examiner observes the smoothness of the range of motion and notes any tenderness. This is illustrated in Figure 17-35.

Shoulder

Symptoms

Although shoulder pain may be related to a primary shoulder disorder, always consider the possibility that shoulder pain is referred from either the chest or the abdomen. Coronary artery disease, pulmonary tumors, and gallbladder disease are commonly associated with pain referred to the shoulder.

Pain is the main symptom of shoulder disorders. Inflammation of the supraspinatus muscle causes pain that is usually worse at night or when the patient lies on the affected shoulder. The pain often radiates down the arm as far as the elbow. The pain is commonly referred to the lower part of the deltoid area and is characteristically aggravated by combing the hair, putting on a coat, or reaching into the back pocket. Diffuse tenderness of the shoulder associated with pain on moving the humerus posteriorly is associated with disorders of the teres minor, infraspinatus, and subscapularis muscles. In this case, the pain usually does not radiate into the arm and is usually absent when the arm is dependent.

The movements of the shoulder occur at the glenohumeral, thoracoscapular, acromioclavicular, and sternoclavicular joints. The glenohumeral joint is a ball-and-socket joint. In contrast to the hip joint, which is also a ball-and-socket joint, in the glenohumeral joint the humerus sits in the very shallow glenoid socket. Therefore the function of the joint depends on the muscles surrounding the socket for stability. These muscles and their tendons form the rotator cuff of the shoulder. For this reason, many shoulder problems are muscular, not bone or joint related, in origin.

Examination

Inspect the shoulder for deformity, wasting, and asymmetry. The shoulder should be palpated for local areas of tenderness. The range of motion for abduction, adduction, external and internal rotation, and flexion is evaluated and compared with that of the other side. Any pain is noted.

Special tests are necessary to determine specific diagnoses. The impingement syndrome, tears of the rotator cuff, and bicipital tendinitis are common. The examinations for these conditions are described in this section.

The impingement syndrome, also known as rotator cuff tendinitis, is usually secondary to sports trauma. Irritation of the avascular portion of the supraspinatus tendon progresses to an inflammatory response termed tendinitis. This inflammatory response later involves the biceps tendon, subacromial bursa, and acromioclavicular joint. With continued trauma, rotator cuff tears and calcification may occur. The most reliable test for the impingement syndrome is the reproduction of pain when the examiner forcibly flexes the patient’s arm with the elbow extended against resistance.

Sudden onset of shoulder pain in the deltoid area 6 to 10 hours after trauma suggests a rotator cuff tear or rupture. Extreme tenderness over the greater tuberosity of the humerus and pain and restricted motion at the glenohumeral joint are usually present. Active abduction of the glenohumeral joint is markedly reduced. When the examiner attempts to abduct the arm, pain and a characteristic shoulder shrug result.

The patient with a rotator cuff injury usually presents with unilateral shoulder pain and weakness. There is difficulty performing overhead or behind-the-back activities and raising arms above shoulder level. There may be pain on sleeping on the affected side.

Rotator cuff injury must be distinguished from adhesive capsulitis, or “frozen shoulder,” which can present with similar symptoms. In adhesive capsulitis there is scarring, thickening, and shrinkage of the shoulder joint capsule; it becomes inflamed and stiff, greatly restricting range of motion and causing chronic pain lasting months to years.

Generalized tenderness anteriorly over the long head of the biceps that is associated with pain, especially at night, should raise suspicion of bicipital tendinitis. In this condition, there is normal abduction and forward flexion. The hallmark of bicipital tendinitis is the reproduction of anterior shoulder pain during resistance to forearm supination. The patient is asked to place the arm at the side with the elbow flexed 90 degrees. The patient is instructed to supinate the arm against the examiner’s resistance. If there is pain in the triceps area with resisted extension of the elbow, tricipital tendinitis may be present.

Elbow

Symptoms

The most common symptom of elbow disorders is well-localized elbow pain.

Although it is a simple hinge joint, the elbow is the most complicated joint of the upper extremity. The distal end of the humerus articulates with the proximal ulna and radius. Flexion and extension of the elbow are effected through the humeroulnar portion of the joint. The radius plays little role in this action; its role is primarily in pronation and supination of the forearm. The ulnar nerve lies in a vulnerable position as it passes around the medial epicondyle of the humerus.

Examination

Palpate the elbow for swelling, masses, tenderness, and nodules. Test flexion and extension.

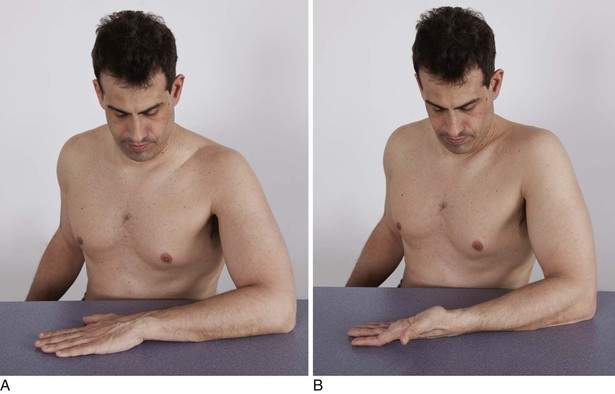

To test for pronation and supination, the elbows should be flexed at 90 degrees and placed firmly on a table. The patient is asked to rotate the forearm with wrist down (pronation), as shown in Figure 17-36A, and wrist up (supination), as shown in Figure 17-36B. Any limitation of motion or pain is noted.

Figure 17–36 Technique for evaluating pronation and supination at the elbow. A, Pronation. B, Supination.

Tennis elbow, also known as lateral epicondylitis, is a common condition characterized by pain in the region of the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. The pain radiates down the extensor surface of the forearm. Patients with tennis elbow often experience pain when attempting to open a door or when lifting a glass. To test for tennis elbow, the examiner should flex the patient’s elbow and fully pronate the hand. Pain over the lateral epicondyle while the elbow is extended is diagnostic of tennis elbow. Another test involves having the patient clench the fist, dorsiflex the wrist, and extend the elbow. Pain is elicited by trying to force the dorsiflexed hand into palmar flexion.

Wrist

Symptoms

The symptoms of wrist disorders include pain in the wrist or hand, numbness or tingling in the wrist or fingers, loss of movement and stiffness, and deformities. Pain in the hand may be referred from the neck or elbow.

The wrist is composed of the articulation of the distal end of the radius with the proximal row of the carpal bones. The stability of the wrist is caused by the banding together of these bones by strong ligaments. The distal ulna does not articulate with any of the carpal bones. On the volar aspect of the wrist, the carpal bones are connected by the carpal ligament. The passage under this ligament is the carpal tunnel, through which the median nerve and all the flexors of the wrist pass. Entrapment of the nerve, known as carpal tunnel syndrome, produces symptoms of numbness and tingling.

Examination

Palpate the patient’s wrist joint between your thumbs and index fingers, noting tenderness, swelling, or redness (Fig. 17-37).

Figure 17–37 Technique for palpation of the wrist joint.

The range of motion of dorsiflexion and palmar flexion is noted. With the forearms fixed, the degree of supination and pronation is evaluated. Is ulnar or radial deviation present?

When the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome is suspected, a sharp tap or pressure directly over the median nerve may reproduce the paresthesias of carpal tunnel syndrome, called Tinel’s sign. Another useful test is for the examiner to stretch the median nerve by extending the patient’s elbow and dorsiflexing the wrist. The development of pain or paresthesias is suggestive of the diagnosis. A third test entails the patient’s holding both wrists in a fully palmar-fixed position for 2 minutes. The development or exacerbation of paresthesias is suggestive of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Hand

Symptoms

Pain and swelling of joints are the most important symptoms of disorders of the hand.

Examination

Palpate the patient’s metacarpophalangeal joints and note swelling, redness, or tenderness, as demonstrated in Figure 17-38. Palpate the medial and lateral aspects of the proximal and distal IP joints between your thumb and index finger, as shown in Figure 17-39. Again, note swelling, redness, or tenderness.

The range of motion of the fingers includes movements at the distal IP joint, the proximal IP joint, and the metacarpophalangeal joints of the fingers and the thumb.

Ask the patient to make a fist with the thumb across the knuckles and then extend and spread the fingers. Normally, the fingers should flex to the distal palmar crease. The thumb should oppose to the distal metacarpal head. Each finger should extend to the zero position in relation to its metacarpal.

Spine

Symptoms

The most common symptom of disorders of the spine is pain. Pain from the thoracic spine often radiates around the trunk along the lines of the intercostal nerves. Pain from the upper lumbar spine may be felt in the front of the thighs and knees. Pain originating in the lower lumbar spine can be felt in the coccyx, hips, and buttocks, as well as shooting down the back of the legs to the heels and feet. The pain is often intensified by movement. Patients with herniated vertebral discs may complain of pain that is exacerbated by sneezing or coughing. Determine whether there is associated numbness or tingling in the lower extremity, which is related to nerve root lesions.

Examination

The cervical spine can be examined with the patient seated. You should inspect the cervical spine from the front, back, and sides for deformity and unusual posture. Test range of motion of the cervical spine. Palpate the paravertebral muscles for tenderness and spasm.

The thoracolumbar spine is examined with the patient standing in front of you. Inspect the spine for deformity or swelling. Inspect the spine from the side for abnormal curvature. Test ranges of motion. Palpate the paravertebral muscles for tenderness. Percuss each spinous process for tenderness.

The ranges of motion tested in the spine are forward flexion, extension, lateral flexion, and rotation.

The presence of a cervical rib may cause coldness, discoloration, and trophic changes as a result of ischemia to an upper extremity. To test for a cervical rib, palpate the radial pulse. Move the arm through its range of motion. Obliteration of the pulse by this maneuver is suggestive of the presence of a cervical rib. Ask the patient to turn the head toward the affected side and take a deep breath while you are palpating the radial pulse on the same side. Obliteration of the pulse by this maneuver is also suggestive of a cervical rib. Often, auscultation over the subclavian artery reveals a bruit suggestive of mechanical obstruction by a cervical rib. Repeat any of these tests on the opposite side. Cervical ribs are rarely bilateral.

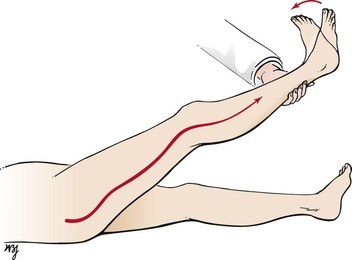

Pain from entrapment of the sciatic nerve is called sciatica. Patients with sciatica describe pain, burning sensation, or aching in the buttocks radiating down the posterior thigh to the posterolateral aspect of the calf. Pain is worsened by sneezing, laughing, or straining at stool. One of the tests for sciatica is the straight leg raising test. The patient is asked to lie supine while the examiner flexes the extended leg to the trunk at the hip. The presence of pain is a positive test result. The patient is asked to plantarflex and dorsiflex the foot. This stretches the sciatic nerve even more. If sciatica is present, this test reproduces pain in the leg. The test is illustrated in Figure 17-40.

Figure 17–40 Straight leg raising test.

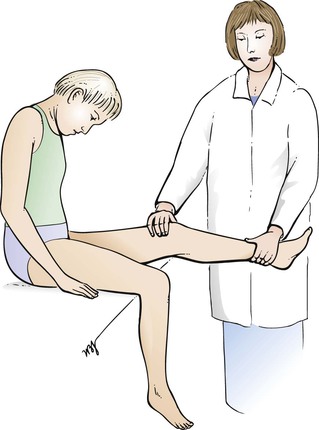

Another test for sciatica is the sitting knee extension test. The patient sits off the side of the bed and flexes the neck, placing the chin on the chest. The examiner fixes the thigh on the bed with one hand while the other hand extends the leg. If sciatica is present, pain is reproduced as the leg is extended. This test is demonstrated in Figure 17-41.

Figure 17–41 Sitting knee extension test.

Hip

Symptoms

The main symptoms of hip disease are pain, stiffness, deformity, and a limp. Hip pain may be localized to the groin or may radiate down the medial aspect of the thigh. Stiffness may be related to periods of immobility. An early symptom of hip disease is difficulty putting on shoes. This requires external rotation of the hip, which is the first motion to be lost with degenerative disease of the hip. This is followed by loss of abduction and adduction; hip flexion is the last movement lost.

Examination

The examination of the hip is performed with the patient standing and lying on the back.

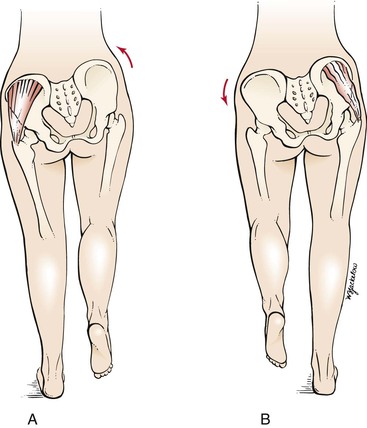

Inspection of the hips and gait has already been described. The Trendelenburg test is used to detect a disorder between the pelvis and the femur. The patient is asked to stand on the “good” leg, as illustrated in Figure 17-42A. The examiner should note that the pelvis on the opposite side elevates, demonstrating that the gluteus medius is working efficiently. When the patient is asked to stand on the “bad” leg, as shown in Figure 17-42B, the pelvis on the opposite side falls. This is a positive Trendelenburg test result.

Figure 17–42 Trendelenburg test. A, Position of the hips when standing on the normal left leg. Note that the hip elevates as a result of contraction of the left hip musculature. B, Position of the hips when standing on the abnormal right leg. Note that the left hip falls as a result of lack of adequate contraction of the right hip muscles.

Ask the patient to lie on his or her back. The hip is acutely flexed on the abdomen to flatten the lumbar spine. Flexion of the opposite thigh is suggestive of a flexion deformity of that hip. Figure 17-43 illustrates the technique.

Figure 17–43 Evaluation for flexion deformity of the hip.

Leg length measurements are useful in evaluating hip disorders. The distance between the anterosuperior iliac spine and the tip of the medial malleolus is measured on each side, and the two measurements are compared. A difference in leg length may be caused by hip joint disorders.

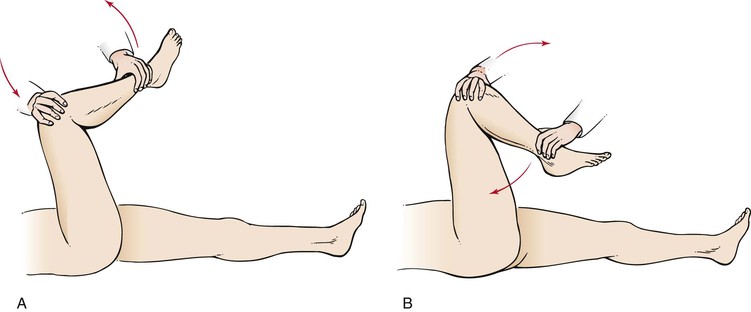

As indicated, loss of rotation of the hip is an early finding in hip disease. To test this movement, ask the patient to lie on his or her back. Flex the patient’s hip and knee to 90 degrees, and rotate the ankle inward for external rotation, as illustrated in Figure 17-44A, and outward for internal rotation, as shown in Figure 17-44B. Restriction of this motion is a sensitive sign of degenerative hip disease.

Knee

Symptoms

Although the knee is the largest joint in the body, it is not the strongest. The knee is a hinge joint between the femur and the tibia and enables flexion and extension. When it is flexed, a small degree of lateral motion is also normal. As with the shoulder, the knee depends on the strong muscles and ligaments around the joint for its stability.

Pain, swelling, joint instability, and limited movement are the main symptoms of knee disorders. Knee pain is exacerbated by movement and may be referred to the calf or thigh. Swelling of the knee indicates a synovial effusion or bleeding into the joint, also known as hemarthrosis. Knee trauma may result in hemarthrosis and limitation of joint motion. Locking of the knee results from small pieces of broken cartilage lodged between the femur and the tibia, blocking full extension of the joint.

Examination

The examination of the knee is performed with the patient standing and lying on the back.

While the patient is standing, any varus or valgus deformity should be noted. Is there wasting of the quadriceps muscle? Is there swelling of the knee? An early sign of knee joint swelling is loss of the slight depressions on the lateral sides of the patella. Inspect for swelling in the popliteal fossa. A Baker‘s cyst in the popliteal fossa may be responsible for swelling in the popliteal fossa, causing calf pain.

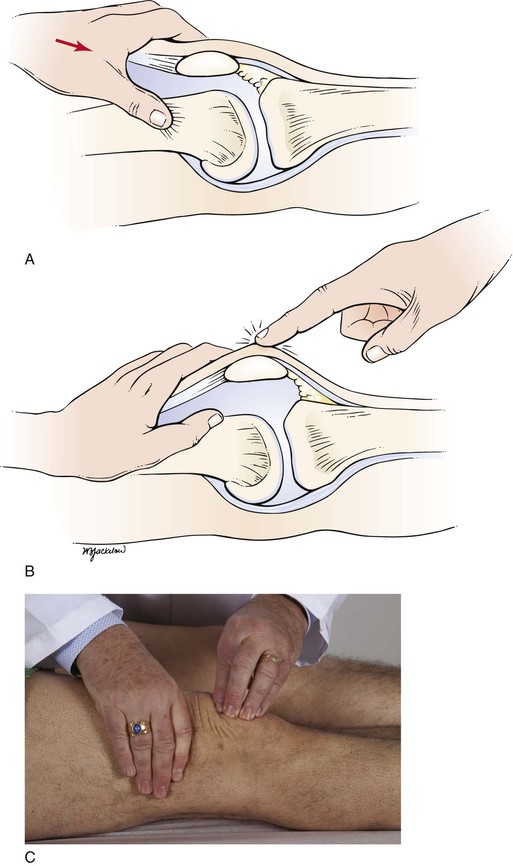

The patient is then asked to lie on the back. The contours of the knee are evaluated. The patella is palpated in extension for tenderness. By stressing the patella against the femoral condyles, pain may be elicited. This occurs in osteoarthritis.

Testing for knee joint effusion is performed by pressing the fluid out of the suprapatellar pouch down behind the patella. Start approximately 15 cm above the superior margin of the patient’s patella and slide your index finger and thumb firmly downward along the sides of the femur, milking the fluid into the space between the patella and the femur. While you maintain pressure on the lateral margins of the patella, tap on the patella with the other hand. This technique is termed ballottement. In the presence of an effusion, a distinct bump is felt in response to your tap, and the transmitted impulse is felt by the fingers on either side of the patella. This technique is shown in Figure 17-45.

Figure 17–45 Technique for testing for knee joint effusion. A, Position of the hand when pushing fluid out of the bursae. B and C, Position for tapping the patella.

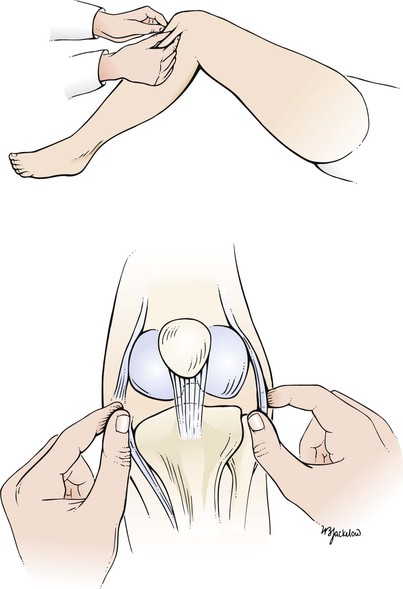

To palpate the collateral ligaments, the patient’s foot should be resting on the bed, with the knee flexed at 90 degrees. Grasp the patient’s leg and, using your thumbs, try to elicit tenderness over the patellar tendon beneath the femoral epicondyles. This technique and a medial collateral ligament rupture are illustrated in Figure 17-46.

Figure 17–46 Top, Technique for testing the collateral ligaments. Bottom, Rupture of the medial collateral ligament.

Another test for collateral ligament rupture is performed by placing the examiner’s left hand on the lateral aspect of the patient’s knee at the level of the joint. The knee is flexed to approximately 25 degrees, and the lower leg is pushed outward by the examiner’s right hand, with the left hand acting as a fulcrum. This maneuver is an attempt to “open up” the medial side of the knee joint. The result should be compared with that on the other side. Abnormal lateral motion is seen in rupture of the medial collateral ligament, as illustrated in Figure 17-47. The maneuver can be used to test for rupture of the lateral collateral ligament by reversing the positions.

The drawer test is used to test for rupture of the cruciate ligaments. The patient is instructed to flex the knee to 90 degrees. The examiner should sit close to the foot to steady it. The examiner then grasps the leg just below the knee with both hands and jerks the tibia forward, as illustrated in Figure 17-48. Abnormal forward mobility of 2 cm or more is suggestive of rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament. This maneuver can be used to test the posterior cruciate ligament by flexing the knee to 90 degrees, steadying the foot, and attempting to jerk the leg backward. Abnormal backward motion of 2 cm or more indicates rupture of the posterior cruciate ligament.

Ankle and Foot

Symptoms

The ankle is a hinge joint between the lower end of the tibia and the talus.

Although symptoms in the ankle and foot usually have a local cause, they can also be secondary to systemic disorders. Symptoms may include pain, swelling, and deformities.

Examination

The examination of the ankle and foot is performed with the patient standing, walking, and then sitting.

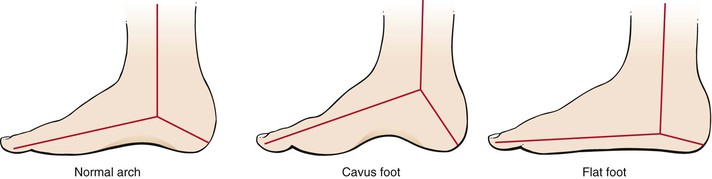

Ask the patient to stand. Inspect the ankles and feet for swelling and deformities. The number and position of toes should be noted. The toes should be straight, flat, and proportional to one another in comparison with the other foot. Compare one foot with the other with regard to symmetry. Are any toes overlapping? Describe abnormalities of the longitudinal arch. A cavus foot has an abnormally high arch. In flatfoot, the longitudinal arch is flatter than normal. Common foot abnormalities are illustrated in Figure 17-49.

Figure 17–49 Common foot abnormalities.

Ask the patient to walk without shoes and socks, and observe the gait. The patient should be able to walk normally, on heels, on toes, and one foot in front of the other (tandem walking). Note any deformities such as the width or length of the feet, heel varus or valgus, calf atrophy, varicose veins, and in-toeing or out-toeing. Take note of the patient’s posture and any shuffling or other abnormality.

Ask the patient to sit with the feet dangling off the side of the bed. Normally, there is mild plantar flexion and inversion of the feet. Palpate the medial and lateral malleoli. The distal portion of the fibula constitutes the lateral malleolus. It extends more distally than the medial malleolus. Palpate the Achilles tendon. Are any nodules present? Is tenderness present?

Test the range of motion at the ankle, which includes dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. The range of motion necessary for normal gait is 10 degrees dorsiflexion and 20 degrees plantar flexion. Ankle joint dorsiflexion with the knee flexed should approach 15 degrees.

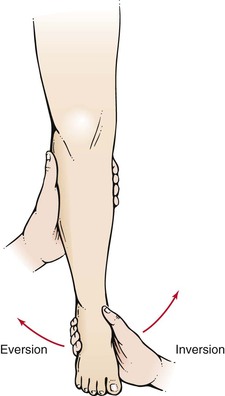

Test the range of motion at the subtalar joint, which includes eversion and inversion. With the patient lying prone on the examination table, hold the patient’s leg in one of your hands, and move the heel with your other hand into inversion and eversion. Measure the excursion of the heel with regard to the bisection of the lower one third of the leg. This technique is illustrated in Figure 17-50. The average range of motion of the subtalar joint is 20 degrees of inversion and 10 degrees of eversion.

Test the range of motion at the midtarsal joint, which includes eversion and inversion. With the patient in the prone position, stabilize the heel with one of your hands, and rotate the forefoot into inversion and eversion. Measure excursion of the plane of the metatarsal heads with regard to the bisection of the heel. This technique is illustrated in Figure 17-51.

The movements of the MTP joints are tested individually. Palpate the head of each metatarsal and the base of each proximal phalanx, as well as the groove between them. Is tenderness or joint effusion present?

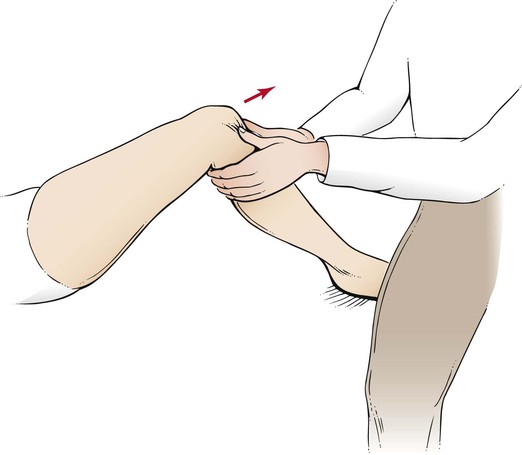

The Achilles tendon, which is the combined tendon of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, may rupture. You can test for its integrity by direct observation and having the patient jump up and down on the balls of the feet or walk on the toes. Another test for its integrity is known as the Thompson-Doherty squeeze test. This test is performed by squeezing the calf while you observe the motion of the foot. Normally, squeezing produces plantar flexion; a ruptured tendon produces little or no motion. When examining the tendon for continuity, remember that the most common place for rupture is approximately 1 to 2 inches (2.5 to 5 cm) proximal to its insertion on the calcaneus. This lies within a region of poorest blood supply that is often referred to as the “watershed area.”

Describe abnormalities of the joints, including hallux abductovalgus (HAV; bunion), and deformities and flexion contractures of the lower digits (hammer toes). Figure 17-52 shows a patient with bilateral bunions and hammer toes. Note the medial deviation of the first metatarsal and the lateral deviation of the hallux at the first MTP joints bilaterally. The hammer toe is best seen on the right second toe.

Figure 17–52 Bunions and hammer toes. Note the medial deviation of the first metatarsal and a lateral deviation of the hallux at the first metatarsophalangeal joints bilaterally. The hammertoe is best seen on the right second toe.

Palpate the soft tissue over the first MTP joint. Is bursal inflammation caused by pressure, friction, or urate deposition? Measure the range of motion of the joint. Dorsiflexion of the hallux is measured against the bisection of the first metatarsal. The normal dorsal range of motion is 65 degrees to 75 degrees. Limitation of motion of this joint is termed hallux limitus and is most commonly caused by osteoarthritis (see next section).

Figure 17-53 depicts ulceration over the distal IP joint of the fourth toe of a patient with chronic tophaceous gout. Note the bunion deformity and underlapping hallux. An acute attack of gout commonly manifests with severe pain, swelling, and inflammation in the first MTP joint, a condition termed podagra. Podagra in a patient with acute gout is pictured in Figure 17-54. Notice the erythema of the left hallux and the generalized swelling of the left foot.

Figure 17–53 Gout of the lesser metatarsophalangeal joints.

Figure 17–54 Acute gout and podagra, left big toe.

Examine the lesser MTP joints. Grasp the MTP joints between your thumb and index finger, and attempt to compress the forefoot. Pain elicited by this maneuver is often an early sign of rheumatoid arthritis. This test is demonstrated in Figure 17-55.

Clinicopathologic Correlations

Rheumatoid arthritis is a common musculoskeletal disorder and is the most destructive and disabling of the principal joint diseases. It is an autoimmune disease that causes chronic inflammation of the joints and of many other organs such as the skin, heart, kidneys, lungs, digestive tract, blood vessels, nervous system, and eyes. However, the joints display the most marked destructive changes. Rheumatoid arthritis is a progressive illness that can cause significant functional disability as a result of pain, swelling, and stiffness of the involved joints. More than 2 million Americans suffer from rheumatoid arthritis, which is 2 to 3 times more common in women than in men. Although rheumatoid arthritis generally occurs between the ages of 40 and 60 years, it can also affect young children and older adults.

The most characteristic changes are in the hands. In the early stages of the disease, there is swelling of the proximal IP, the metacarpophalangeal, and the wrist joints. As the disease progresses, there is bone erosion, which produces the classic signs of the disease. The most characteristic deformity of the fingers is ulnar deviation at the metacarpophalangeal joints. The two main deformities of the IP joints are the swan-neck deformity and the boutonnière deformity.

The swan-neck deformity, which results from shortening of the interosseous muscles, produces flexion of the metacarpophalangeal joints, hyperextension of the proximal IP joints, and flexion of the distal IP joints. The boutonnière deformity is a flexion deformity of the proximal IP joints with hyperextension of the distal IP joints. Figure 17-56 shows the hands of a woman with rheumatoid arthritis. Note the marked ulnar deviation of the metacarpophalangeal joints. Figure 17-57 depicts the characteristic swan-neck deformity.

Figure 17–57 Rheumatoid arthritis. Note the swan-neck deformity.

Osteoarthritis, or degenerative joint disease, is very common, affecting more than 20 million people in the United States. Osteoarthritis is related mostly to aging. Before age 45 years, osteoarthritis occurs more frequently in men; after age 55 years, it occurs more frequently in women. In the United States, all races appear to be affected in equal proportions. A higher incidence of osteoarthritis exists in the Japanese population, whereas black people from South Africa, people from the East Indies, and people from southern China have lower rates.

Osteoarthritis is a type of arthritis that is caused by the breakdown and eventual loss of the cartilage of one or more joints. In most cases, the inflammatory response is minimal in comparison with that of rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoarthritis causes pain, swelling, and reduced motion in the joints. The form of osteoarthritis depends on the joints involved. Osteoarthritis commonly affects the hands, feet, spine, and large weight-bearing joints, such as the hips and knees. One of the joints frequently involved is the distal IP joint of the hands. Progressive enlargement of these joints is termed Heberden’s nodes. As the disease progresses, the proximal IP joints may become involved, resulting in Bouchard’s nodes. Figure 17-58 shows the hands of a woman with osteoarthritis.

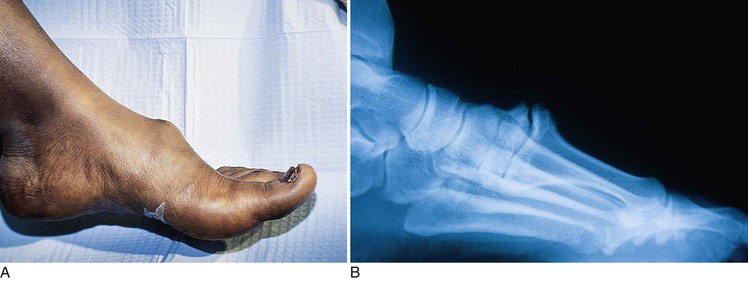

Another common podiatric complaint is an exostosis at the metatarsocuneiform joint, which produces a painful dorsal lesion. Figure 17-59A depicts this type of problem; Figure 17-59B is an x-ray film of the foot showing the bony abnormality.

Figure 17–59 A, Exostosis at the metatarsocuneiform joint. B, X-ray film of the affected metatarsocuneiform joint.

As discussed in Chapter 5, The Skin, psoriasis is one of the most common skin diseases in the United States. The pustular variant is characterized by pustules localized to the palms and soles. The patient may be quite ill, with fever and leukocytosis. Figure 17-60 shows pustular psoriasis of the soles. Note the hyperkeratosis on an erythematous base.

Figure 17–60 Pustular psoriasis.

Joint disease develops in approximately 7% of patients with psoriasis. The most common form of psoriatic arthritis (70%) is asymmetrical arthritis involving only two or three joints at a time. Arthritis mutilans is the most deforming type of psoriatic arthritis. In the most severe cases, there is osteolysis of the phalangeal and metacarpal joints, resulting in “telescoping of the digits,” also known as the opera-glass deformity. The hands of a patient with this deforming type of psoriatic arthritis are shown in Figure 17-61.

Figure 17–61 Psoriatic arthritis.

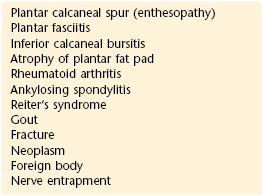

Table 17-6 lists the most common disorders associated with heel pain. Plantar fasciitis is an inflammation of the plantar fascia, usually caused by excessive, repetitive stretching. The plantar fascia is a broad band of fibrous tissue that runs along the bottom surface of the foot, attaching at the bottom of the calcaneus and extending to the forefoot. The pain is often most severe with the first steps in the morning or when rising from a chair. When the plantar fascia is excessively stretched, plantar fasciitis can occur, leading to arch pain, heel pain, and heel spurs. The most common causes of plantar fasciitis are:

• Overpronation (flatfoot), which results in the arch’s collapsing with weight bearing

• A foot with an unusually high arch

• A sudden increase in physical activity

• Excessive weight on the foot, usually attributed to obesity or pregnancy

Gout is a metabolic disease characterized by high levels of uric acid, recurrent attacks of acute arthritis, and deposition of urate crystals in and around the joints. The initial manifestation is frequently acute pain in the first MTP joint, often waking the patient from sleep. Even at rest, the pain is severe, but the slightest movement of the joint is agonizing. Within a few hours, the joint becomes swollen, shiny, and red. The higher the level of uric acid, the more likely the patient is to develop tophi, which are subcutaneous and periarticular deposits of urate crystals. The commonly involved sites are over the first MTP joint, the finger, the ear, the elbow, and the Achilles tendon. Figure 17-62 shows a gouty deposit on the big toe. Figure 17-63 shows the arms of a patient with chronic tophaceous gout who has large tophi on her elbows, as well as smaller tophi on her hands. Tophi frequently develop over the distal IP joints of the fingers and in the olecranon and prepatellar bursae. Figure 17-64 shows the hands of a patient with tophi on her fingers.

Figure 17–62 Gout affecting big toe.

Figure 17–63 Gout. Note tophi on the elbows and hands.

Figure 17–64 Gout. Note tophi on the fingers.

A sudden onset of pain along the midshaft of the lesser metatarsals should alert the clinician to the possibility of a stress fracture. The pain is usually pinpoint and can occur spontaneously even in the absence of overt trauma. Early diagnosis is often based on clinical suspicion, because x-ray examinations may appear normal. With continued weight bearing and in the absence of treatment, the hairline fracture may widen and cause symptoms to become more severe.

Pain and swelling on the medial aspect of the ankle, along the course of the posterior tibial tendon, may be indicative of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD). This condition is usually worsened by activity and may be accompanied by an inability to perform a single limb heel raise on the affected side. PTTD is one of the most common causes of acquired flatfoot in adults.

Table 17-7 lists disorders associated with first MTP joint pain. Metatarsalgia is a common ailment that affects the plantar forefoot, typically occurring in young people who engage in physical activities such as dancing or jogging. Patients with high-arch foot types are particularly susceptible. Any activity that places force on the ball of the foot—even walking—can cause metatarsalgia. Sesamoiditis is a general description for any inflammatory condition affecting the sesamoid bones. The sesamoids are tiny bones within the flexor tendons that run to the big toe. With repetitive stress, they can eventually become inflamed and even fractured. Sesamoiditis can be distinguished from other forefoot conditions by its gradual onset and location. The pain usually begins as a mild ache under the first metatarsal head and increases gradually as the aggravating activity is continued; the pain may build to an intense throbbing.

Morton’s neuroma is a common foot problem associated with pain, swelling, and inflammation of an intermetatarsal nerve, usually between the third and fourth metatarsal heads. The digital nerve traveling between the adjacent metatarsal heads becomes entrapped or pinched during the push-off phase of gait. Symptoms of this condition include sharp pain, burning, cramping and even a lack of feeling in the toes supplied by that nerve. Symptoms of Morton’s neuroma can occur during or after application of significant pressure on the forefoot area while walking, standing, jumping, or sprinting. A patient may also complain that it feels as if a marble or pebble were inside the ball of the foot. Constricting shoes can worsen the condition by pinching the nerve between the toes, causing discomfort and extreme pain.

To evaluate a patient with a suspected Morton’s neuroma, try to reproduce the pain by gently pushing the adjacent metatarsal heads together. Next, try to palpate the neuroma by pressing your thumb into the third interspace. Finally, hold the patient’s first, second, and third metatarsal heads with one of your hands and the fourth and fifth metatarsal heads in the other, and push half the foot up while pushing half the foot down slightly. In a patient with Morton’s neuroma, this maneuver may elicit an audible click, known as Mulder‘s sign. Local injections, shoe gear modification, and orthoses may prove helpful; however, surgery may also be necessary.

Bunions are one of the most frequently encountered musculoskeletal pathologic conditions seen in the foot. Also referred to as an HAV deformity, a bunion is characterized by a medial deviation of the first metatarsal and a lateral deviation of the hallux at the first MTP joint (see Fig. 17-52). Degenerative arthritis, limitation of motion, and pain can develop as the articular cartilage is slowly worn away by malalignment of the joint. Occasionally, the laterally deviated hallux encroaches on the second toe, causing it to either under- or overlap. This can cause pain not only to the bunion, but to the second toe as well. Symptoms can be made worse as the result of pressure within the toe box of a narrow or high-heeled shoe.

Figure 17-65 shows hallux abductovalgus deformity, flexion contractures of the IP joints, and bowstringing of the extensor tendons. This is a typical presentation in the geriatric age group. Note the hyperkeratotic lesion over the right bunion from shoe pressure. Bunion deformities can be a source of undue pressure in diabetic patients, leading to ulceration and infection. A large pressure ulceration over the medial eminence of the first MTP joint resulting from shoe irritation in a diabetic patient is shown in Figure 17-66.

Figure 17–66 Hallux abductovalgus deformity and ulceration.

Hammer toes are characterized by a flexion contracture of the proximal IP joint of one or more of the lesser toes, resulting in a dorsal prominence. Shoe pressure may lead to a reactive hyperkeratosis or “corn” to form on the top of the toe. Bowstringing of the extensor tendons may also be seen. The patient shown in Figure 17-52 has both bunion and hammertoe deformities.

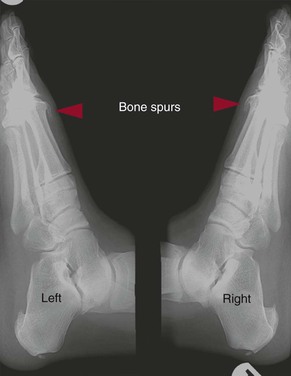

Hallux limitus and hallux rigidus are common conditions characterized by pain and a limitation of motion at the first MTP joint. Limitus is a term that refers to decreased motion of a joint; this is the early stage. Rigidus denotes a joint that has very little, if any motion available; this is the later stage. As the condition progresses from hallux limitus to rigidus, a bone spur may develop at the first MTP joint and prevent the big toe from bending as much as it needs to during gait. Pain and stiffness of the first MTP joint during activities such as walking or running are common symptoms of both conditions. The patient in Figure 17-67 has hallux rigidus and a large dorsal-medial bump. Notice the callus on the bump caused by increased pressure and rubbing on shoes. Figure 17-68 is an x-ray examination of a patient with bilateral hallux rigidus. Note the bony spurs. Osteoarthritis of the first MTP joint is evident with narrowing of the joint space and periarticular spurring.

Figure 17–67 Hallux rigidus. Note the large dorsal-medial bump on the first metatarsophalangeal joint.

Figure 17–68 Hallux rigidus. X-ray examination showing the bone spurs on the first metatarsophalangeal joints bilaterally.

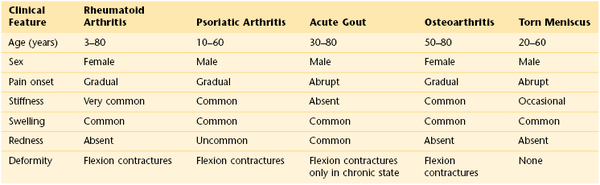

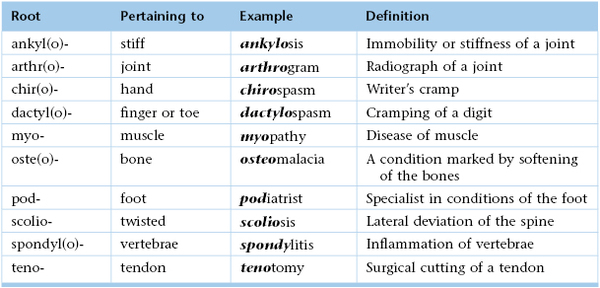

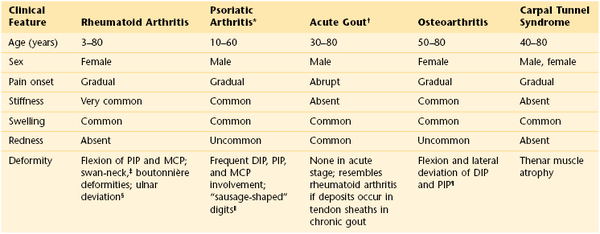

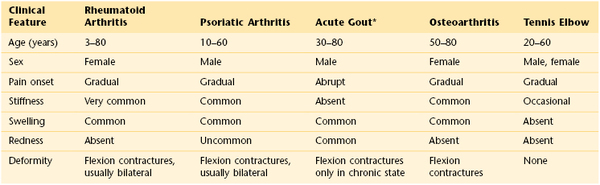

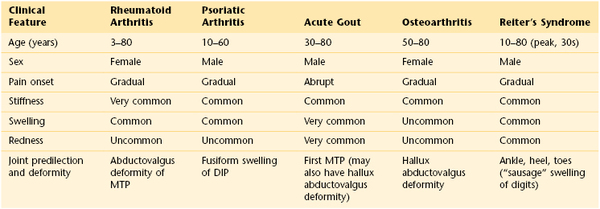

Table 17-8 summarizes the clinical features that differentiate rheumatoid arthritis from osteoarthritis. Table 17-9 summarizes some of the features of diseases affecting the hands and wrists. Table 17-10 outlines the clinical features that differentiate common musculoskeletal disorders affecting the elbow. Table 17-11 lists the clinical features that differentiate significant diseases affecting the knee. Table 17-12 lists the clinical features differentiating diseases of the foot.

Table 17–8

Clinical Features Differentiating Rheumatoid Arthritis from Osteoarthritis

| Clinical Feature | Rheumatoid Arthritis* | Osteoarthritis† |

| Patient’s age (years) | 3–80 | Older than 45 |

| Morning stiffness | More than 1 hour | Less than 1 hour |

| Disability | Often great | Variable |

| Joint distribution | ||

| •Distal interphalangeal joint | Rare | Very common |

| •Proximal interphalangeal joint | Very common | Common |

| •Metacarpophalangeal joint | Very common | Absent |

| •Wrist | Very common | Absent |

| Soft tissue swelling | Very common | Rare |

| Interosseous muscle wasting | Very common | Rare |

| Swan-neck deformity | Common | Rare |

| Ulnar deviation | Common | Absent |

* See Figures 17-56 and 17-57.

† See Figure 17-58.

Table 17–9

Clinical Features Differentiating Diseases Affecting the Hands and Wrists

* Needlepoint pitting of the nails is often associated with psoriatic arthritis. See Figures 5-14 and 5-16.

† See Figure 17-54.

‡ See Figure 17-57.

§ See Figure 17-56.

‖ See Figure 17-61.

¶ See Figure 17-58.

DIP, Distal interphalangeal joint; MCP, metacarpophalangeal joint; PIP, proximal interphalangeal joint.

Table 17–10

Clinical Features Differentiating Diseases Affecting the Elbow

* See Figure 17-63, which shows a patient with chronic tophaceous gout and painless tophi on the elbows.

Table 17–12

Clinical Features Differentiating Diseases Affecting the Foot

DIP, Distal interphalangeal joint; MTP, metatarsophalangeal joint.

The bibliography for this chapter is available at studentconsult.com.

Bibliography

Aldrige T. Diagnosing heel pain in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:332.

Balint GP, et al. Foot and ankle disorders. Best Prac Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17:887.

Benjamin M, McGonagle D. Histopathologic changes at “synovio-entheseal complexes” suggesting a novel mechanism for synovitis in osteoarthritis and spondylarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3601.

Brault MW, et al. Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults, United States, 2005. MMWR. 2008;58:421.

Buchbinder R. Plantar fasciitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2159.

Busija L, et al. Role of age, sex, and obesity in the higher prevalence of arthritis among lower socioeconomic groups: a population-based survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:553.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Arthritis. [Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/ [Updated October 31, 2012. Accessed February 19, 2013] .