5 The menstrual cycle, menstrual disorders, infertility and the menopause

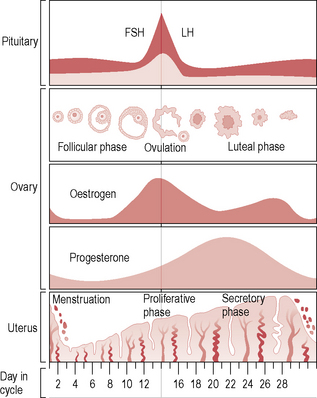

The menstrual cycle

Menstrual disorders

Menorrhagia

Aetiology

Pathological causes for menorrhagia are:

• Uterine fibroids (submucosal)

• Anovulatory bleeds, e.g. menarche, perimenopausal and with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)

• Endometrial pathology, e.g. endometrial polyps or hyperplasia

• Coagulation disorders, e.g. von Willebrand’s disease or anticoagulant treatment

In 40–60% of women no cause is found and the condition is termed dysfunctional uterine bleeding.

Presentation

Women may complain of heavy periods or be referred after a diagnosis of iron-deficiency anaemia.

History

• What is the cycle length, including the longest and shortest cycles?

• For how many days does the bleeding last?

• For how many days is bleeding heavy?

• How much sanitary protection is needed – how often does the woman need to change her sanitary towel or tampon? Does she ever need to wear both together or ‘double up’ towels?

• Does she experience flooding (sudden loss of blood, which exceeds the absorbency of the protection, causing embarrassing blood leak through to clothes or bed linen)?

• Does she pass clots of blood? If so, what size?

• Does she need to take time off work during her period?

• How else does her bleeding affect her life (social life, sex life)?

• What contraception is being used?

• Are there any anaemia symptoms (tiredness, shortness of breath, palpitations)?

First-line treatments

The following three alternative treatments have equal efficacy:

• Mefenamic acid – mefenamic acid 500 mg is taken three times daily from the first day of bleeding until the bleeding is tailing off. This, or another non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent, is particularly helpful if there is associated dysmenorrhoea.

• Combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) – this may be suitable where contraception is also required or the cycle is irregular.

• Progestogens – continuous progestogens usually cause amenorrhoea and may be helpful in women who are severely anaemic and who can tolerate the side effects. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate is an effective long-term treatment, or oral norethisterone three times daily may be used in the short term.

Second-line treatments

Complications of transcervical resection of the endometrium

Dysmenorrhoea

Clinical features

Important questions in the history are:

• What is the nature of the pain?

• When does the pain start in relation to the period?

• What medication does the woman take to relieve the pain?

• Does she have any non-menstrual pain or dyspareunia?

• How does the pain impact on her life – does she take time off work, does it limit her social life?

Amenorrhoea and oligomenorrhoea

Definitions

• Amenorrhoea is the absence of menstruation.

• Primary amenorrhoea is the failure to establish menstruation.

• Secondary amenorrhoea is the absence of periods for 6 months or more after previously regular menstruation.

• Oligomenorrhoea is fewer than four periods occurring within a 12-month interval.

Incidence

Primary amenorrhoea is experienced by 0.3% of girls and 3% of women have secondary amenorrhoea.

Primary amenorrhoea

Aetiology

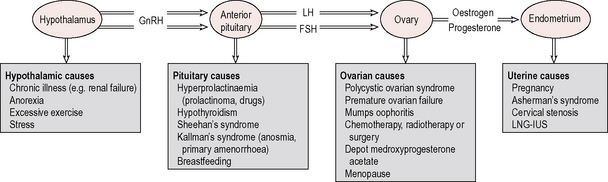

The two commonest causes of primary amenorrhoea are Turner’s syndrome and constitutional delay (Fig. 5.2). Other causes include pregnancy, hypothalamic causes (stress, excessive exercise, anorexia), androgen insensitivity syndrome, hypothyroidism, primary ovarian failure and anatomical causes (uterine malformation, imperforate hymen and vaginal septum). Drugs that cause amenorrhoea are chemotherapeutic agents (damage to ovaries) or others such as phenothiazines, which are dopamine antagonists.

Secondary amenorrhoea

The causes of amenorrhoea are illustrated in relation to the hypothalamopituitary–ovarian–endometrial axis in Figure 5.2.

History

• Is there a possibility of pregnancy?

• What contraception is used – could it be causing amenorrhoea?

• Is there a history of previous pregnancy complications, such as postpartum haemorrhage, evacuation of retained products of conception or termination of pregnancy?

• What was the nature of the periods when present – regularity, length, heaviness of flow?

• Is exercise excessive? Has there been recent weight loss?

• Is there a history of chronic illness, radiotherapy or chemotherapy?

• Does the woman experience headaches or visual symptoms?

• Are there associated endocrine symptoms such as obesity, hirsutism, acne or symptoms of hypothyroidism?

• Are there associated menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes, night sweats or vaginal dryness?

Intermenstrual and postcoital bleeding

Aetiology of intermenstrual and postcoital bleeding

Investigations

Cervical smear should be taken if it has not been performed within the last 3 years.

Colposcopy and cervical biopsy should be performed if there is suspicion of cervical malignancy.

Premenstrual syndrome

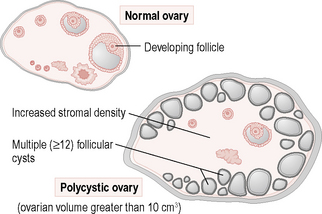

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

Investigations

A hormone profile should be taken around day 5. The investigations usually show:

Serum FSH, thyroid function tests and prolactin levels are usually normal in women with PCOS.

Infertility

Definitions

• Subfertility – failure to conceive after 1 year of regular unprotected sexual intercourse.

• Infertility – no chance of spontaneous conception, for example because of bilateral salpingectomy or azoospermia.

• Primary subfertility – the woman has never been pregnant.

• Secondary subfertility – the woman has had at least one pregnancy before.

Aetiology

Fifteen per cent of couples have more than one cause for their infertility. The causes of infertility are shown in Table 5.1.

| Male factor (30–50%): |

| Erectile problems (e.g. psychological or neurological disease) |

| Ejaculatory dysfunction (e.g. retrograde ejaculation after prostatic surgery) |

| Sperm dysfunction (motility, normality, survival) |

| Testicular failure (e.g. cryptorchidism, mumps orchitis, torsion, chemo- or radiotherapy, Klinefelter’s, hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism) |

| Genital tract obstruction (e.g. vasectomy, incidental ligation of vas deferens at hernia surgery, infection with gonorrhoea, Chlamydia or tuberculosis) |

| Congenital absence of the vas (e.g. cystic fibrosis) |

| Ovulatory problems (30%): |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome (70% of anovulatory infertility) |

| Hypogonadotrophic anovulation (e.g. excess exercise, anorexia, Sheehan’s, Kallman’s syndrome) |

| Hyperprolactinaemia (e.g. prolactinoma, drugs) |

| Genetic causes (e.g. Turner’s syndrome, androgen insensitivity) |

| Premature ovarian failure |

| Tubal problems (20%): |

| Infection (e.g. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, pelvic inflammatory disease, tuberculosis) |

| Adhesions (e.g. surgery or endometriosis, but not unruptured appendicitis) |

| Previous ectopic pregnancy |

| Other causes: |

| Endometriosis (5%) |

| Fibroids (up to 10%) |

| Uterine anomalies (1%) |

| Unexplained infertility (25%) |

History

A full medical history should be taken from both partners. Important questions for the woman are:

• Has the woman been pregnant before and what were the outcomes of the pregnancies? Has she had an ectopic pregnancy or evacuation of the uterus or other previous pregnancy complications?

• Has she had any previous abdominal operations?

• Is there a history of sexually transmitted infection or pelvic inflammatory disease?

• Have there been any other medical problems, such as previous radiotherapy, chemotherapy or thyroid disease?

• Does the woman take any medication that might affect her fertility?

• What is the menstrual cycle length and regularity?

• Does she experience dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia or menorrhagia?

• What is the frequency of sexual intercourse?

The partner should also be asked specifically:

• Have any previous partners become pregnant by him?

• Has he had any previous operations, such as inguinal hernia repair or orchidopexy?

• Have there been any recent or previous serious illnesses?

• Is there a history of chemotherapy or radiotherapy?

• Has he ever been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection?

• Does he experience any erectile or ejaculatory difficulty?

• Does he take any medications which might affect spermatogenesis, such as cimetidine, antihypertensives or anabolic steroids?

• Does he smoke and, if so, how many cigarettes per day?

• How much alcohol does he drink?

• Does his occupation involve possible exposure to chemicals or an adverse testicular environment (e.g. long-distance lorry driver)?

Investigations

Female investigations

Hormone profile

The following tests should be requested on all women complaining of subfertility:

• LH (day 2–5 of the menstrual cycle) – LH greater than 10 IU/l and a raised LH:FSH ratio suggests PCOS.

• FSH (day 2–5 of the menstrual cycle) – FSH greater than 10 IU/l suggests a poor prognosis as it is associated with poor ovarian reserve (ovarian failure) and a likely poor outcome from assisted conception, unless donor eggs are used.

• Progesterone (day 21 for a 28-day cycle, otherwise about 8 days before expected menstruation) – progesterone greater than 30 nmol/l suggests that ovulation has occurred.

• Testosterone – testosterone concentration 2.5–5 nmol/l is consistent with PCOS. If testosterone is greater than 5 nmol/l, then further investigation is needed for other causes of androgen excess.

• Prolactin – prolactin >1000 mU/ml suggests hyperprolactinaemia and if repeat test confirms this, then investigations for prolactinoma should be initiated. Prolactin levels less than 1000 mU/ml may be due to stress, exercise or venepuncture.

Male investigations

Semen analysis

The normal values for semen analysis are given in Table 5.2.

| Volume | 2–5 ml |

| Count | >20 million per ml |

| Motile forms | >50% progressively mobile and >25% rapidly progressive |

| Normal forms | >15% normal shape |

Semen deficiency definitions

Management

Anovulatory infertility

Other medication should be reviewed where this may be the cause of anovulation.

Endometriosis

IVF is the most effective treatment where the above measures have not been successful.

Assisted conception techniques

Assisted conception techniques aim to:

• Pharmacologically stimulate ovaries to produce several eggs.

• Prepare the semen by washing, and in ICSI selecting a highly motile normal form.

• Optimize fertilization by approximating the sperm and egg closely (IUI) or facilitating fertilization in vitro (IVF or ICSI).

Ovulation induction

Oral drugs such as clomifene and tamoxifen or parenteral drugs such as FSH can stimulate ovulation.

In vitro fertilization

Alternative infertility options

Acceptance of childlessness and adoption should also be discussed from an early stage.

Ovarian failure

Definitions

Menopause

The menopause can only be diagnosed retrospectively, 1 year after the last menstrual period.

Management

Types of hormone replacement therapy

Side effects of hormone replacement therapy

Risks of hormone replacement therapy

Breast cancer

The risk increases by 2.3% for each year of HRT use (Table 5.3) and declines to a normal risk 5 years after stopping. The risk is higher for oestrogen and progestogen preparations than for oestrogen alone. The risk of breast cancer with tibolone is somewhere between that of oestrogen alone and that of combined preparations.

Table 5.3 Breast cancer cases per year of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) use

| No HRT | 45 cases per 1000 women |

| 5-year HRT | 47 cases per 1000 women |

| 10-year HRT | 51 cases per 1000 women |

| 15-year HRT | 57 cases per 1000 women |

(Reproduced from Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52705 women with breast cancer and 108411 women without breast cancer. Lancet 1997; 350: 1047–1059, with permission.)

Benefits of hormone replacement therapy

Premature ovarian failure

Summary

• Menorrhagia is one of the commonest presenting complaints to gynaecologists.

• Tranexamic acid is the most effective first-line treatment for menorrhagia.

• The LNG-IUS and endometrial ablation techniques are highly effective after failure of medical treatment for menorrhagia.

• Constitutional delay and Turner’s syndrome are the usual causes of primary amenorrhoea.

• Intermenstrual and postcoital bleeding are almost always pathological and should be investigated.

• PCOS can present with a spectrum of clinical, biochemical or ultrasonographic manifestations.

• Subfertility is often multifactorial – male factor (30–50%), ovulatory (30%), tubal (20%) and unexplained (25%).

• Symptom control and osteoporosis prevention are important indications for HRT.

• All women considering HRT need individual assessment and careful counselling about the risks, benefits and uncertainties.

• Osteoporosis prevention is vital for women with premature ovarian failure.