Chapter 42 The menopause

From the mean age of 40 (±5) years a woman’s ovaries become less receptive to the effects of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), either because the number of receptor-binding sites on each follicle is decreasing or because increasing numbers of follicles are disappearing, or both. The effect is that oestrogen secretion declines and fluctuates and anovulation becomes more frequent. The fluctuations are a major factor in causing the menstrual disturbances that occur in some women in the years preceding the menopause (see Ch. 28). The negative feedback to the hypothalamus and pituitary gland is less effective, with the result that FSH levels begin to rise. The release of FSH is also increased by the falling levels of inhibin secreted by the ovarian follicles.

The remaining ovarian follicles become increasingly resistant to the higher FSH levels and oestrogen secretion is reduced still further until oligomenorrhoea, and later, amenorrhoea result. If the amenorrhoea persists for 12 months, with or without menopausal symptoms, the menopause has been reached. If the clinician is doubtful whether the menopause has occurred, it can be confirmed by measuring serum FSH on several occasions. A level of more than 40 IU/L indicates menopause (Table 42.1). The measurement of oestrogen levels is not helpful, as the levels of oestrone, oestradiol and oestriol fluctuate even after the menopause, particularly in the first 12 months. A change in the ratio of oestradiol to oestrone occurs, oestrone becoming the dominant circulating oestrogen. After the menopause, any circulating oestrogen detected is synthesized in the peripheral fat by aromatization of androstenedione, derived mainly from the adrenal cortex, with some from the ovarian stroma.

Table 42.1 Postmenopausal plasma hormone levels measured 1 year after the menopause

| FSH (IU/L) | 90 –110 |

| LH (lU/L) | 60 –70 |

| Oestradiol (pmol/L) | 30 –100 |

| Oestrone (pmol/L) | 100 –150 |

| Total testosterone (nmol/L) | 1–3 |

| Free testosterone (pmol/L) | 3–9 |

| Dihydrotestosterone (pmol/L) | 100 –300 |

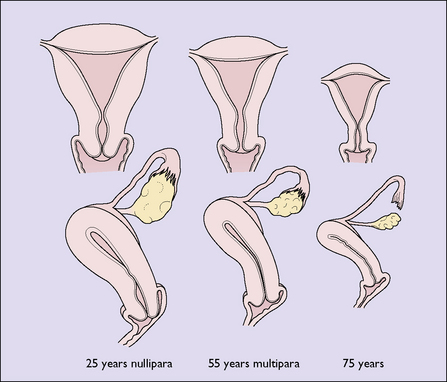

CHANGES IN THE GENITAL TRACT AFTER THE MENOPAUSE

The decline in circulating oestrogen after the menopause leads to atrophy of the organs of the genital tract and the breasts (Fig. 42.1). The ovaries, the Fallopian tubes and the uterus become progressively atrophic. In the uterus, the muscle fibres are converted into fibrous tissue and any fibroids present atrophy. The vaginal epithelium becomes thinner and less rugose, and intermediate cells replace superficial cells. The vaginal secretions diminish, as does the vaginal acidity, and pathogenic organisms grow more easily. The urethral mucosa may become atrophic. In some women, urinary symptoms of frequency, dysuria and incontinence result (see Ch. 39). The pelvic floor muscles lose their tone as their blood supply is reduced; relaxation of the muscles increases and uterovaginal prolapse may become evident (Ch. 38). The external genitals slowly become atrophic, and in old age the labia majora may lose their fat, revealing the labia minora.

SYMPTOMS OF THE CLIMACTERIC

MANAGEMENT OF THE CLIMACTERIC

POSTMENOPAUSAL BLEEDING

Irregular vaginal bleeding may also occur in women not taking HRT. The causes are listed in Table 42.2. As 15% of women who have postmenopausal bleeding will be found to have a malignancy, investigations include inspection of the vagina, a Pap smear and an endometrial curettage or biopsy, even if the clinical diagnosis appears to be atrophic vaginitis or a cervical polyp. Treatment depends on the cause.

Table 42.2 Causes of postmenopausal bleeding (800 reported cases)

| Percentage | |

|---|---|

| No demonstrable lesion | 25 |

| Oestrogen therapy | 20 |

| Atrophic vaginitis | 15 |

| Endometrial adenocarcinoma | 15 |

| Endometrial polyp or hyperplasia | 15 |

| Cervical carcinoma | 4 |

| Benign cervical lesions (polyps) | 4 |

| Ovarian tumour (mostly malignant) | 1 |

| Bleeding from urinary tract | 1 |

OSTEOPOROSIS

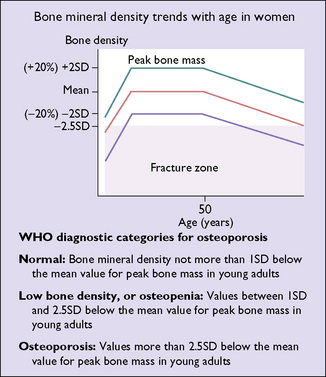

Osteoporosis is defined as a reduced bone mass per unit volume and, in clinical practice, as the relation to the degree to which bone mineral density is reduced. There are several types of osteoporosis (Box 42.1), but that which concerns women most is postmenopausal osteoporosis. The WHO has provided diagnostic criteria for the categories of osteoporosis (Fig. 42.2).

The chance that a woman will develop osteoporosis depends on genetic inheritance, her peak bone mineral density (which is reached between the ages of 15 and 25), and the rate at which she loses bone. Until the age of 40 bone loss is balanced by bone formation; after this about 0.5% of the bone mass is lost annually (Fig. 42.3). Following the menopause, bone loss varies from 1 to 7% a year depending on the individual, averaging 3% a year.

This amount of bone loss continues for 10 years and then reduces to between 0.5 and 1.0% per year.

Prevention of osteoporosis

A mature woman should take the following measures to try to prevent osteoporosis:

A postmenopausal woman with risk factors should also consider starting to take HRT, as oestrogen effectively prevents bone loss. If HRT is contraindicated, or she chooses not to take the hormones, an alternative is to take one of the bisphosphonates and seek specialist help. Before starting this treatment a more accurate prognosis can be obtained if her bone mineral density is measured using DEXA. Depending on the result, she should be advised whether she needs treatment or to wait and repeat the scan 2 years later (see Fig. 42.2). It is unclear whether exercise helps to reduce the rate of bone loss, but it may increase bone strength and reduce the chance of falls.