20 The masseters and their treatment with botulinum toxin

Summary and Key Features

• The masseter muscle may become hypertrophied distorting the mandibular angle

• Masseteric hypertrophy may be a cause of bruxism and facial pain syndromes

• Botulinum toxin may be used to treat both medical pain syndromes and to change facial shape by changing the mandibular angle

• Botulinum toxin may replace surgical and orthodontic techniques in selected patients in both medical and aesthetic indications

• Botulinum toxin may allow us to beautify patients by altering the lower facial width and converting the face to a more youthful triangular or heart-shaped face

History

Evidence has begun to accumulate that the masseteric hypertrophy has other effects besides the bulk it directly confers because of the muscle volume. In line with theories of bone deposition and development, Wu found in 2010 that this muscle development may have effects on the underlying bone growth and volume. Bone growth and volume are under the influence and related to the activity of the muscles attached to the bone. A bone responds to the activity and strength of the muscles attached to it by thickening and the corollary is that bone will decrease when the muscular force acting on the bone is decreased, as reported by Tsai et al. Molina et al found that the masseter neuromuscular end plates are developed by 12 weeks’ fetal gestation. By restraining mouth opening, Habib and co-workers showed by the use of suturing that restricted fetal temporomandibular joint movement influences the process of endochondral bone formation of condylar cartilage. These effects on bone may explain the trimming effect that botulinum toxin has on the facial shape may be above and beyond the effects of what would be expected by a decrease in muscle bulk alone (Fig. 20.1). However, not all authors (e.g. Chang et al) believe that bony resorption occurs after botulinum toxin injection.

Anatomy

Masseter muscle

1. The superficial part arises from the zygomatic process of the maxilla and from the anterior two-thirds of the lower border of the zygomatic arch

2. The middle part originates from the deep surface of the anterior two-thirds of the zygomatic arch and from the lower border of the posterior one-third of the arch

3. The deep part arises from the deep surface of the zygomatic arch.

Surface anatomy of the masseter muscle

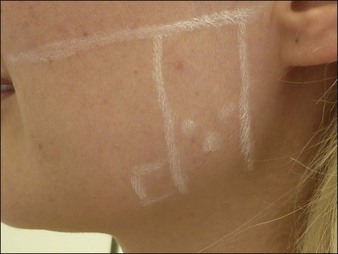

The muscle is easily outlined, with the superior border represented by the zygomatic arch and the inferior border being the inferior border of the mandible, The posterior border is the posterior border of the mandible, and the anterior border is easily seen in those with hypertrophy by asking the patient to clench their teeth. Anteriorly, along the jawline the masseter muscle will give way to a gap where often the arterial pulsation of the facial artery may be felt, and superior to this the hardness of the contracting masseter muscle may be contrasted with the softer connective tissue of the face anterior to the contracting muscle (Fig. 20.2).

Raison d’être for botulinum injection of the masseters in the lower face

Treatment of the masseter muscle for shaping and beautification of the lower face

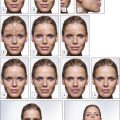

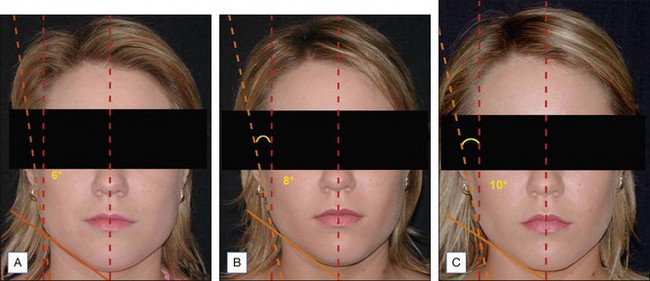

Aesthetic recontouring of the lower face has been gradually developing as a concept initially with East Asian patients, but more recently also in Western patients. There has been a gradual increase in understanding of the use of botulinum toxin in the treatment of masseteric hypertrophy to promote a better facial appearance and enhance beauty. However, there is a definite gender difference in what is perceived to be attractive. Male facial shape is ideally full of sharp angles. The ideal facial female shape has been stated to be heart shaped, oval or base-up triangular or similar (Fig. 20.3).

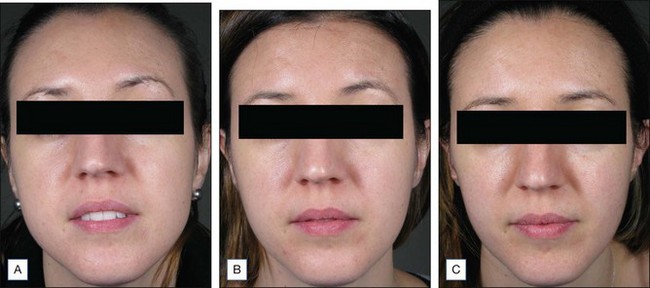

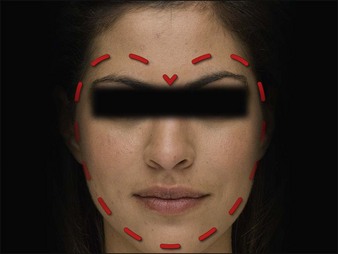

There are many surgical procedures that have been described to decrease width of the lower third of the face, for example by Yang et al and Ying et al, and there is general agreement that attractiveness in female faces has as one of its components an aesthetically pleasing angles of the lower third of the face. In 2011 Liew looked at the similarities in truly beautiful people in different racial groups, and found that if one transposes a vertical line from the midline to intersect with the angle cast between the line drawn along the body of the mandible and tissue overlying the ascending ramus of the mandible it will form an acute angle (Fig. 20.4A–C). This angle is more acute (a lower angle) if the facial shape is square, such as one cast with masseter hypertrophy or parotid enlargement. It is less acute or greater if the facial shape is more triangular or the lower facial width is decreased. Hence, in Figure 20.3, one can see the improvement in attractiveness as one moves towards a greater ‘angle of beauty’, the ideal being 9–12°.

Treatment method

Injecting masseters

The patient is asked to clench the jaw and the masseter palpated, outlining the anterior and posterior borders of the masseter muscle. Three to five injection points are used depending on the masseter bulk and markings placed at the site of maximum bulge, which is usually in the lower half of the muscle. The injection points are placed below a line drawn from the tragus to the angle of the mouth (see Fig. 20.2) and at least 1 cm from the borders of the muscles. Injecting outside these limits may interfere with other masticatory muscles, especially superolaterally, and the salivary glands posteriorly and inferiorly. The injections are placed deeply, as superficial placement may not reach the deeper heads of the muscle and produce n appearance of a chipmunk chewing on nuts when the patient is eating. Possibly this is due to the action of the functional deep head pushing against a treated and flaccid superficial head.

Pearl 5

Injections should be deep and inferior to a line between the tragus and the angle of the mouth.

Pearl 6

Dose will depend on muscle bulk, but 15–40 units of onabotulinum toxin may be required per side.

Masseter treatments may be repeated at 1–3-monthly intervals until the desired shape is attained (Fig. 20.5). Patients will readily report most often that their jaw clenching, morning headaches, sore teeth or other symptoms are better even after the first injection session. However, if symptoms are not improved or substantially settled this is a sign for reinjection of similar dose, otherwise often a lower dose than initially may be used.

Quite often there will be asymmetry to the masseteric hypertrophy or even unilateral hypertrophy. Doses should be tailored to this event but, unless it is totally unilateral, often it is better to inject some on both sides but more obviously on the palpably stronger and visibly bigger side (Fig. 20.6).

Complications

1. Occasionally the botulinum toxin will drift into anterior and superficial muscles especially the risorius limiting the smile somewhat

2. Weakness when chewing foods that require powerful biting and grinding such as an apple or steak (can be limited to some degree if the injections are kept to the lower part of the muscular bulk)

3. Injecting especially older patients with large muscle bulk may allow a redundancy to develop anteriorly, with jowling and sagging due to the volume reduction of the skin envelope overlying the masseters

4. Over-hollowing of the infrazygomatic area causing a somewhat haggard appearance

5. Intramuscular or subcutaneous hematoma

6. Muscle bulging on mastication (usually temporary and mostly avoided by deep injection).

Ahlberg J, Rantala M, Savolainen A, et al. Reported bruxism and stress experience. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 2002;30:405–408.

Ahn J, Horn C, Blitzer A. Botulinum toxin for masseter reduction in Asian patients. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery. 2004;6:188–191.

Berkovitz B, Kirsch C, Moxham BJ, et al. Interactive Head and Neck. Primal Pictures Ltd; 2003. Software version 1.10

Chang CS, Bergeron L, Yu CC, et al. Mandible changes evaluated by computed tomography following Botulinum Toxin A injections in square-faced patients. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2011;35:452–455. Epub 2010 Nov 20

Habib H, Hatta T, Udagawa J, et al. Fetal jaw movement affects condylar cartilage development. Journal of Dental Research. 2005;84:474–479.

Iglesias-Linares A, Yáñez-Vico RM, et al. Common standards in facial esthetics: craniofacial analysis of most attractive black and white subjects according to People magazine during previous 10 years. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2011;69(6):e216–24. Epub 2011 Apr 5

Jankovic J, Orman J. Botulinum A toxin for cranial-cervical dystonia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurology. 1987;37:616–623.

Kim NH, Chung JH, Park RH, et al. The use of botulinum toxin type A in aesthetic mandibular contouring. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2005;115:919–930.

Kwon JS, Kim ST, Jeon YM, et al. Effect of botulinum toxin type A injection into human masseter muscle on stimulated parotid saliva flow rate. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2009;38:316–320. Epub 2009 Feb 23

Lagueny A, Deliac MM, Julien J, et al. Jaw closing spasm – a form of focal dystonia? An electrophysiological study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1989;52:652–655.

Lavigne GJ, Montplaisir JY. Restless legs syndrome and sleep bruxism: prevalence and association among Canadians. Sleep. 1994;17:739–743.

Liew S 2011 Presentation, Hong Kong, December 9

Liew S, Dart A. Nonsurgical reshaping of the lower face. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2008;28:251–257.

Molina W, Reyes E, Joshi N, et al. Maturation of the neuromuscular junction in masseters of human fetus. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology. 2010;51:537–541.

Moore AP, Wood GD. The medical management of masseteric hypertrophy with botulinum toxin type A. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1994;32:26–28.

Reddy R, White DR, Gillespie MB. Obstructive parotitis secondary to an acute masseteric bend. ORL Journal of Otorhinolaryngology and its Related Specialties. 2012;74(1):12–15. Epub 2011 Dec 8

Santamato A, Panza F, Di Venere D, et al. Effectiveness of botulinum toxin type A treatment of neck pain related to nocturnal bruxism: a case report. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine. 2010;9(3):132–137.

Smyth AG. Botulinum toxin type A treatment of bilateral masseteric hypertrophy. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1994;32:29–33.

Tsai CY, Chiu WC, Liao YH, et al. Effects on craniofacial growth and development of unilateral botulinum neurotoxin injection into the masseter muscle. American Journal of Orthodontal and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 2009;135(2):142.e1–142.e6. discussion 142–143

Tsai CY, Shyr YM, Chiu WC, et al. Bone changes in the mandible following botulinum neurotoxin injections. European Journal of Orthodontics. 2011;33(2):132–138. Epub 2010 Sep 30

Van Zandijcke M, Marchau MM. Treatment of bruxism with botulinum toxin injections. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1990;53:530.

Wu WT. Botox facial slimming / facial sculpting: the role of botulinum toxin-A in the treatment of hypertrophic masseteric muscle and parotid enlargement to narrow the lower facial width. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 2010;18:133–140.

Yang J, Wang L, Xu H, et al. Mandibular oblique ostectomy: an alternative procedure to reduce the width of the lower face. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 2009;20(suppl 2):1822–1826.

Ying B, Wu S, Yan S, et al. Intraoral multistage mandibular angle ostectomy: 10 years’ experience in mandibular contouring in Asians. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 2011;22(1):230–232.

inch) 30-gauge hypodermic needle.

inch) 30-gauge hypodermic needle.