Chapter 20 The Management of Delayed and Non-unions of the Distal Humerus

Introduction

A non-united fracture of the distal humerus threatens the function of the entire upper limb. The involved elbow joint may be stiff, or grossly unstable, painful and associated with peripheral nerve dysfunction.1 The non-union will compromise function of either the ipsilateral shoulder, hand, or both.

While fractures of the distal humerus are uncommon (2–6% of all fractures),2,3 the unique regional anatomy, with the articular surfaces supported by limited bone yet subject to substantial reactive joint forces in normal daily activities, presents significant impediments to successful surgical fixation and functional outcome.

Background/aetiology

As our patients live longer, the incidence of upper extremity fractures including those involving the distal humerus is increasing. In addition, what we are seeing are more complex fractures occurring at or distal to the olecranon sulcus and associated with osteoporotic bone. These factors are providing the surgeon with an increasing challenge to achieve stable internal fixation that facilitates bone healing without complication. It is also leading to more interest in the use of total elbow arthroplasty as a primary form of fracture treatment.4 Closed or open distal humeral fractures are also seen in younger patients associated with higher-energy injuries. In each of these situations failure of bone healing has become a well-recognized adverse sequela.5 Additional risk factors contributing to non-union include obesity, alcoholism and patient unreliability, as well as advanced osteoporosis.6

Presentation, investigation and treatment options

The patient’s physical examination involves a careful assessment of the entire upper limb. The mobility of the adjacent joints including the ipsilateral shoulder, forearm, wrist and hand may be compromised from prolonged immobilization, postsurgical swelling or peripheral nerve injury or compression. The latter is particularly relevant as ulnar nerve compromise is now well recognized as a sequela of elbow trauma and surgical reconstruction and may be the source of pain as well as motor and sensory dysfunction in the hand.1

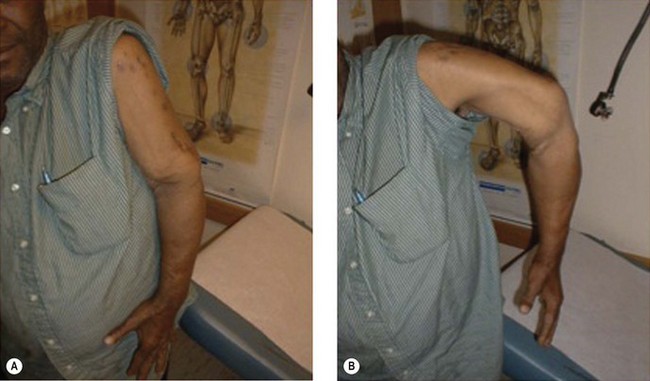

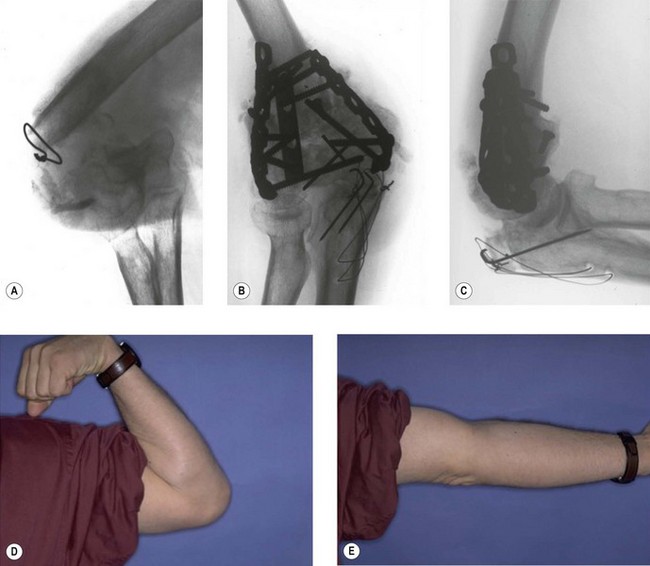

Examination of the affected elbow must document the location and extent of previous surgical incisions, the adequacy and compliance of the soft tissue envelope, and joint mobility and/or instability. A grossly unstable or flail non-union will prevent the patient from effectively lifting the forearm against gravity (Fig. 20.1).

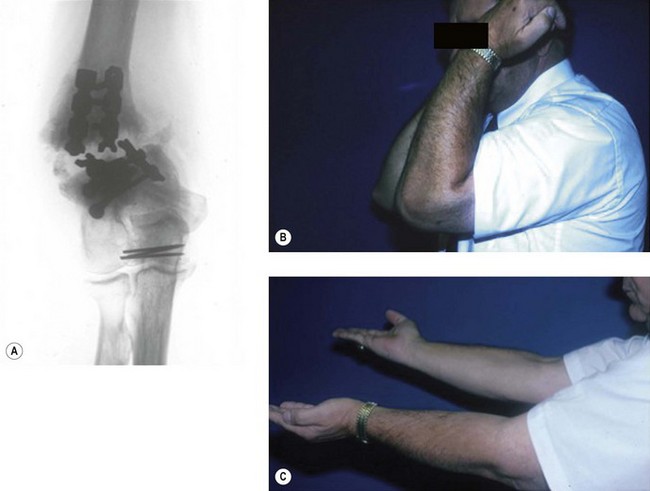

Owing to the disturbed local anatomy at the non-union site, standard radiographs of the elbow may not adequately define the morphology of the nonunion. While evaluation of the original fracture and/or postoperative radiographs will be helpful, these are not always available. The distal articular fragment(s) of the non-union may be flexed due to capsular contracture and appear on the radiographs to be anatomically smaller than in reality.7 In these situations, or when non-unions occur within the articular surfaces, 3-D CT imaging may be extremely useful.

Treatment options will include a hinged functional brace for patients too infirm for surgery or who do not wish to undergo an additional surgical procedure; realignment with internal fixation and capsular release, or total elbow arthroplasty.1

Summary Box 20.1

A non-united fracture of the distal humerus creates a dysfunctional upper limb.

Evaluation of the patient must include the function and mobility of the shoulder, wrist and hand.

Surgical techniques and rehabilitation

The tactics of surgical treatment of a distal humerus non-union will depend upon the location and morphology of the non-union. Non-unions may be classified as supracondylar, intra-articular, or combined extra- and intra-articular (Table 20.1).7

Table 20.1 Classification of distal humeral non-unions based upon anatomical location

| Supracondylar | Flail elbow – gross instability at the non-union site with a synovial membrane that will require debridement. The bone ends characteristically are sclerotic |

| Bone loss – substance loss that may require an interposition structural graft | |

| Combined extra- and intra-articular | The non-union involves both the supracondylar level and extends into the articular components |

| Intra-articular | The non-union is characterized primarily by involvement of the articular condyles |

| Osteochondral | This represents a subset of articular non-unions where the original fracture involved a shear injury to the anterior articular surface |

| Low transcondylar | Non-unions at this level will have very distorted bony anatomy of the distal fragment and require modification of internal fixation methods |

| Infected | These may be salvaged but represent unique injuries |

Non-union at the supracondylar level

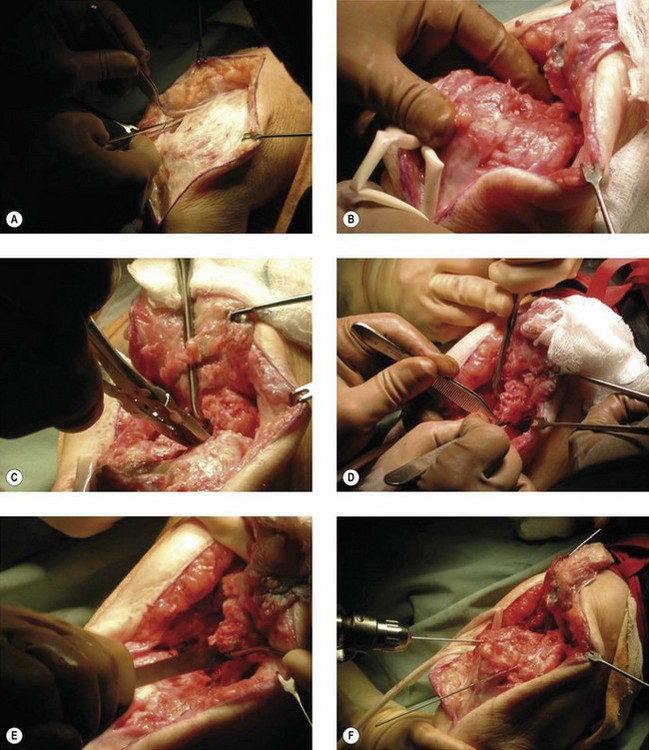

We prefer using a sterile tourniquet, although some might avoid this owing to the potential length of the reconstructive procedure. A straight dorsal surgical incision provides extensile exposure; however, prior incisions must be considered and included if possible (Fig. 20.2 (video)).

The ulnar nerve must be carefully mobilized, preferably for at least 6 cm proximal and distal to the cubital tunnel. The nerve is commonly surrounded by fibrosis that will limit its normal excursion following elbow mobilization, unless sufficiently mobilized and placed into the surrounding soft tissues (Fig. 20.3).

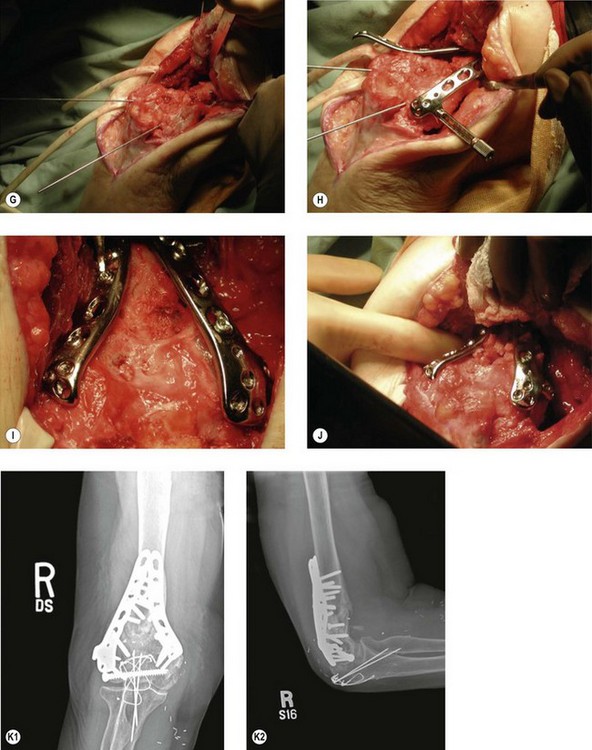

The techniques of plate fixation will vary considerably based on the size of the distal fragment, the extent of the underlying osteoporosis, as well as the type and availability of implants. Although anatomically shaped implants have been developed for the distal humerus, the often-distorted anatomy that occurs with non-unions will frequently require contouring of standard plates. A third plate has proven to be useful in cases where limited bone exists in the distal fragment particularly if it is only possible to achieve one screw purchase per plate.8 Given that there is often incomplete bony contact, cancellous iliac crest graft should be used to fill in areas of bony defect (Fig. 20.4).

Total elbow arthroplasty

The indications for total elbow arthroplasty have been well documented and include patients with very complex non-unions compounded with medical comorbidities, extreme osteoporosis, advanced patient age or those with pre-existing arthritis.9–12 A recent prospective randomized study comparing open reduction and internal fixation with total elbow arthroplasty in elderly patients with displaced intra-articular distal humerus fractures was performed by McKee et al.13 They reported an improved and more predictable 2-year functional outcome in those patients treated with arthroplasty than with internal fixation. Total elbow arthroplasty was felt to be preferable in this subset of patients, in whom stable internal fixation was not possible.

Clinical Pearl 20.2 Treatment of supracondylar non-union

Combined intra- and extra-articular non-unions

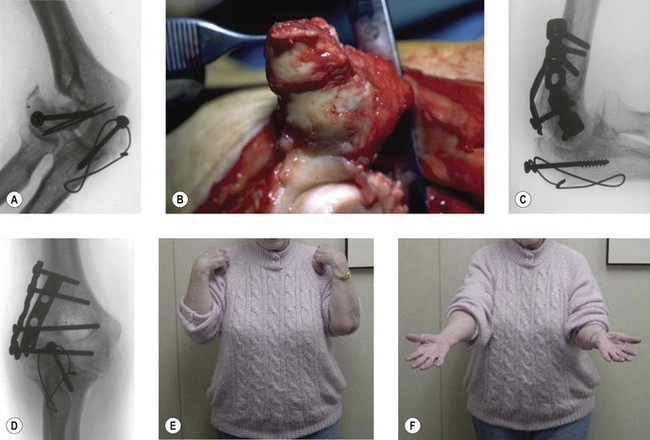

The operative technique of reconstruction of a non-union, both within the articular surfaces as well as more proximally, is extremely complex. Preoperative planning is essential to determine whether or not such surgery should be considered. If surgical treatment is offered to the patient, the extensile exposure, capsular release, and articular and bony realignment are similar to that already described for supracondylar non-unions. With primarily lateral-sided problems, however, an extensile lateral approach can be used. By elevating both the brachioradialis and the long radial wrist extensor anteriorly and the lateral triceps posteriorly, the elbow can be ‘hinged’ open, exposing the anterior articular surface (Fig. 20.5). Fixation again requires plate contouring and, depending on the fracture configuration, a third plate may once more be necessary.

Intra-articular non-union

Isolated articular non-unions are very uncommon.7 They are made more complex by the fact that the articular component has little or no subchondral bone, limited space for implant application, and a substantial risk of avascular necrosis and/or fragmentation.

Realignment and stable internal fixation of these osteochondral fragments is challenging both with regard to obtaining stable internal fixation and avoiding loss of vascularity. Headless screws placed from anterior to posterior will provide stable fixation, and if this is combined with a full capsulectomy enhanced motion can be achieved (Fig. 20.5).

Complex non-unions – infected

In the setting of an intra-articular distal humeral fracture complicated by failed internal fixation and active sepsis, the goals of treatment include eradication of the infection, realignment of the articular surface, fracture healing and maximizing the functional outcome. Alternatives include arthrodesis or distraction arthroplasty,14 but these are equally difficult to achieve and have far less function than a preserved elbow articulation. Implant arthroplasty is contraindicated in the face of active or even quiescent infection.

Summary Box 20.3 Complex non-unions

The same principles and surgical techniques apply as for non-union at the supracondylar level.

Clinical Pearl 20.3 Complex non-unions

Outcome and literature review

Operative fixation of supracondylar distal humeral non-unions have variable functional results. In one of the largest publications, with a total of 52 patients, Helfet and Rosen treated 27 non-unions at the supracondylar level. Union was achieved in all 27, though complications were found in eight patients: four with postoperative ulnar nerve neuropathy, two with radial nerve neuropathy, two with deep infection and one with a compartment syndrome.3 In the senior author’s experience of 39 non-unions at the supracondylar level, all but four united after the index procedure, with only one patient requiring a second operation, following which union was successful.7 A subgroup of 15 patients with very unstable non-unions at the supracondylar level were reviewed by Ring et al.15 Of these, 12 of the non-unions united. Three failed to heal and were converted to total elbow arthroplasty. In the 12 that achieved union, the average arc of ulnohumeral motion was 95°, with an excellent Mayo Elbow Performance Index in two, good in nine and fair in one. When comparing these very unstable supracondylar-level non-unions with those with retained hardware or fibrous non-unions, it was evident that these are a more complex subgroup to treat.

Patients in whom non-unions extended into the ulnotrochlear joint fared less well despite gaining successful union. Increasing experience with these more complex non-unions led McKee to retrospectively review a combination of his own patients and those of the senior author.16 Seven of 13 patients reviewed had a malaligned intra-articular non-union. The mean age of the entire group was 39.7 years, with an average preoperative arc of motion of 43°. Nine patients had preoperative ulnar neuropathy. The elbow reconstructions were performed an average of 13.4 months following the original injury. At a mean follow-up of 25 months, union was achieved in all patients, with an average postoperative arc of motion of 97° and with a Mayo Elbow Performance Index that was excellent in two, good in eight and fair in three.

Use of vascularized fibular grafts17 has resulted in successful outcomes in two of the senior author’s patients where the original problem included complex wounds leading to infection and segmental bone loss. This technique has also had a successful outcome in four of five patients in the reported experience of Beredjiklian et al.18

The senior author has reported three cases of intra-articular non-union.19 One involved the anterior capitellum, one the capitellum and trochlea and one the posterior trochlea. These were originally treated with internal fixation. The preoperative arc of elbow flexion was 80°, 35° and 25°, respectively. All three non-unions healed, with an average follow-up of 34 months. The capitellar non-union showed partial avascular necrosis on follow-up X-rays. All patients obtained elbow flexion of 130° with an average flexion contracture of 27°. The mean Mayo Elbow Performance Index was 85 points.

The senior author reported on five patients with infected intra-articular non-unions over a 4-year period. In this series, four of the five patients achieved union of the fracture with the Ilizarov external fixator, although secondary cancellous bone grafting was required at the supracondylar level. These patients obtained a functional range of motion.20 Similarly, in a series of six patients by Brinker et al,21 five patients achieved union with the Ilizarov external fixator. In both series the operative approach involved removal of the hardware, release of the ulnar nerve, debridement, autogenous bone grafting and application of the external fixator.

It has been widely thought that adult patients presenting with advanced ulnar nerve lesions with intrinsic muscle wasting had a poor prognosis of recovery after operative neurolysis. However, in a study of 20 consecutive patients treated following primary failure of fracture fixation and with an associated ulnar nerve lesion, a high rate of patient satisfaction was found as well as improved ulnar nerve sensory and motor function.22

Experience with linked semi-constrained total elbow arthroplasty for patients who are not amenable to internal fixation has been reported in a series by Cil et al.23 Ninety-one patients underwent total elbow arthroplasty for distal humeral non-union, with a mean follow-up of 6.5 years. Sixty-seven patients had no or mild pain, whereas 79 had moderate or severe pain preoperatively. Seventy-seven patients rated the outcome as better or much better. Twenty patients had fair or poor Mayo Elbow Performance Scores. Implant failure risk was increased by the following factors: patient age less then 65 years, two or more prior surgeries and a history of infection. In a review of 19 patients, 14 of whom had complex distal humeral non-unions associated with an unstable or flail elbow, Ramsey et al10 found functional motion in all of the patients with total elbow arthroplasty. The average arc of flexion ranged from 25° to 128°. The patients had little or no pain, although four complications were recorded.

The use of total elbow arthroplasty as a salvage procedure is also supported by the work of Friggie et al.24

Complications of treatment

Following revision surgery for distal humeral non-unions, elbow contracture, ulnar nerve dysfunction and pain associated with the implant are all potential complications.15 Elbow contracture release should be offered to patients with an ulnohumeral arc of motion of ≤80°. Ulnar nerve neuropathy may be transient but when it is not consideration should be given to obtaining electrical studies and re-exploring the nerve to be sure it is fully released and transposed.

1 Jupiter JB. Complex fractures of the distal part of the humerus and associated complications. Instr Course Lect. 1995;44:187-198.

2 Ackerman G, Jupiter JB. Non-union of fractures of the distal end of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A:75-83.

3 Helfet DL, Kloen P, Anand N, et al. Open reduction and internal fixation of delayed unions and nonunions of fractures of the distal part of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85A:33-40.

4 Frankle MA, Herscovici D, DiPasquale TG, et al. A comparison of open reduction and internal fixation and primary total elbow arthroplasty in the treatment of intraarticular distal humerus fractures in women older than age 65. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:473-480.

5 Gallay SH, McKee M. Operative treatment of nonunions about the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;370:87-101.

6 Volgas D, Stannard J, Alonso J. Nonunions of the humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;419:46-50.

7 Jupiter JB. The management of nonunion and malunion of the distal humerus: a 30-year experience. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:742-750.

8 Jupiter J, Goodman LJ. The management of complex distal humerus nonunion in the elderly by elbow capsulectomy, triple plating, and ulnar nerve neurolysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1:37-46.

9 Morrey BF, Adams RA. Semiconstrained elbow replacement for distal humeral nonunion. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1995;77:67-72.

10 Ramsey ML, Adams RA, Morrey BF. Instability of the elbow treated with semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. 1999;81:38-47.

11 McKee M, Jupiter JB. Semiconstrained elbow replacement for distal humerus nonunion. J Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77B:665-666.

12 Pugh DM, McKee M. Advances in the management of humeral nonunion. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11:48-59.

13 McKee MD, Veillette CJ, Hall JA, et al. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial of open reduction-internal fixation versus total elbow arthroplasty for displaced intra-articular distal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:3-12.

14 Morrey BF. Post-traumatic contracture of the elbow: operative treatment, including distraction arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:601-618.

15 Ring D, Gulotta L, Jupiter JB. Unstable nonunions of the distal part of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85A:1040-1046.

16 McKee M, Jupiter J, Toh CL, et al. Reconstruction after malunion and nonunion of intraarticular fractures of the distal humerus. J Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76-B:614-621.

17 Gerwin M, Weiland AJ. Vascularized bone grafts to the upper extremity: indications and technique. Hand Clin. 1992;8:509-523.

18 Beredjiklian PK, Hotchkiss RN, Athanasian ER, et al. Recalcitrant nonunion of the distal humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;435:134-139.

19 Ring D, Jupiter JB. Operative treatment of osteochondral nonunion of the distal humerus. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:56-59.

20 Ring D, Jupiter JB, Toh S. Salvage of contaminated fractures of the distal humerus with thin wire external fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;359:203-208.

21 Brinker MF, O’Connor DP, Crouch CC, et al. Ilizarov treatment of infected nonunions of the distal humerus after failure of internal fixation: an outcomes study. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:178-184.

22 McKee MD, Jupiter JB, Bosse G, et al. Outcome of neurolysis during post-traumatic reconstruction of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1998;80B:100-105.

23 Cil A, Veillette CJH, Sanchez-Sotelo J, et al. Linked elbow replacement: a salvage procedure for distal humeral nonunion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1930-1950.

24 Friggie MP, Inglis AE, Mow CS, et al. Salvage of non-union of supracondylar fracture of the humerus by total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71A:1058-1065.