16

The management of achalasia and other motility disorders of the oesophagus

Introduction

For many years oesophageal manometry was done using water-perfused systems that were difficult to set up and with many technical constraints. These were gradually replaced by solid-state pressure transducers.With further miniaturisation and developments in computer software, thin catheters containing multiple pressure recording transducers (high-resolution manometry) have become widely available, leading to novel ways of displaying pressure information as isobaric contour plots using colour gradations to indicate different pressures (high-resolution oesophageal pressure topography). The latter systems have disclosed considerable new information about oesophageal motor disturbances, resulting in new criteria (Chicago classification, Table 16.1) to define these disorders.1 Further details of manometry techniques are described in Chapter 12 and manometry of a normal swallow is shown in Fig. 12.1.

Table 16.1

The Chicago classification of oesophageal motility

| Diagnosis | Criteria |

| Achalasia type I | Classic achalasia: mean IRP > upper limit of normal, 100% failed peristalsis |

| Achalasia type II | Achalasia with oesophageal compression: mean IRP > upper limit of normal, no normal peristalsis, pan-oesophageal pressurisation with ≥ 20% of swallows |

| Achalasia type III | Mean IRP > upper limit of normal, no normal peristalsis, preserved fragments of distal peristalsis or premature (spastic) contractions with ≥ 20% of swallows |

| Oesophagogastric junction outflow obstruction | Mean IRP > upper limit of normal, some instances of intact peristalsis or weak peristalsis with small breaks such that the criteria for achalasia are not met |

| Distal oesophageal spasm | Normal mean IRP, ≥ 20% premature contractions |

| Hypercontractile oesophagus | At least one swallow DCI > 8000 mmHg • s • cm with single peaked or multipeaked contraction |

| Absent peristalsis | Normal mean IRP, 100% of swallows with failed peristalsis |

| Weak peristalsis with large peristaltic defects | Mean IRP < 15 mmHg and > 20% swallows with large breaks in the 20 mmHg isobaric contour (> 5 cm in length) |

| Weak peristalsis with small peristaltic defects | Mean IRP < 15 mmHg and > 30% swallows with small breaks in the 20 mmHg isobaric contour (2–5 cm in length) |

| Frequent failed peristalsis | > 30%, but < 100% of swallows with failed peristalsis |

| Rapid contractions with normal | Rapid contraction with ≥ 20% of swallows, DL > 4.5 s |

| Hypertensive peristalsis (nutcracker oesophagus) | Mean DCI > 5000 mmHg • s • cm, but not meeting criteria for hypercontractile oesophagus |

DCI, distal contractile integral; DL, distal latency; IRP, integrated relaxation pressure.

Achalasia

The term ‘achalasia’ comes from Greek, meaning ‘failure to relax’. It was first used by Sir Arthur Hurst early in the 20th century, although the clinical features were first described in 1697 by Thomas Willis. It is conventionally defined by the absence of peristalsis (this does not mean the absence of contractions) in association with a lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) that fails to relax completely. High-resolution pressure topography recognises this classic type (type I) but also considers two other types of achalasia, where there can be either pan-oesophageal pressurisation to more than 30 mmHg with at least 20% of swallows (type II) or preserved fragments of distal peristaltic activity or premature (spastic) contractions with at least 20% of swallows (type III).2 These last two types probably represent the entity usually referrred to as ‘vigorous achalasia’ when seen on conventional manometry. Primary or idiopathic achalasia needs to be considered separately from secondary achalasia. While symptoms may be similar, the presence of a specific aetiology can influence management. These secondary causes are discussed later in this chapter.

Primary achalasia

This is an uncommon condition with an incidence in the Western world that is probably less than 1 case per 100 000 people per year.3 It is due to progressive loss of ganglion cells in the myenteric plexus of unknown cause. The neural loss is somewhat selective as there is particularly severe loss of inhibitory nitrergic neurotransmission.4,5 This process is often accompanied by an inflammatory infiltrate that has led to many theories regarding aetiology. While there is circumstantial evidence of viral exposure and autoimmune phenomena, neither provides a satisfactory explanation for all patients.5

Investigations

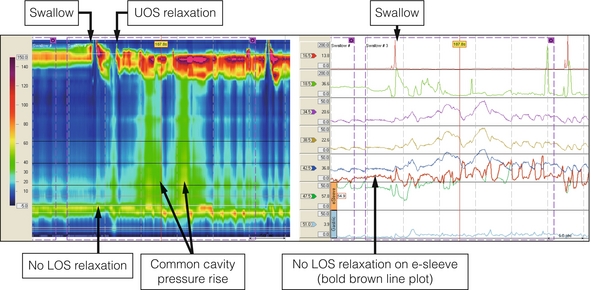

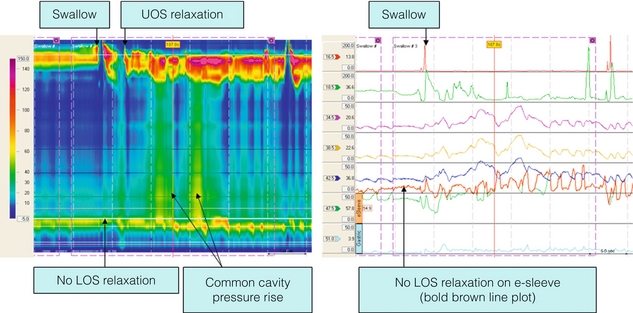

A firm diagnosis can only be made by oesophageal manometry. High-resolution techniques suggest that conventional manometry, however, only diagnoses about a quarter of patients with achalasia on the basis of the classic features of a hypertensive lower oesophageal sphincter that does not relax completely on swallowing, aperistalsis of the oesophageal body and a raised resting pressure in the oesophagus (Fig. 16.1). The other two variants can be separated by the Chicago classification and this may be clinically relevant. Limited evidence suggests that patients with type II achalasia with pan-oesophageal pressurisation do respond well to treatment, but this seems not to be the case for type III.2

Figure 16.1 Achalasia. High-resolution manometry from a patient presenting with dysphagia and regurgitation. The swallow is followed by a ‘common cavity’ rise in oesophageal pressure indicating filling. LOS relaxation is absent and there is a positive oesophagogastric pressure gradient. Upper oesophageal sphincter (UOS) relaxation shortly after the swallow was related to regurgitation of oesophageal contents.

Treatment

Botulinum toxin injection

This involves the injection of 100 units of botulinum toxin into the LOS.

When compared to pneumatic dilatation in a randomised trial, only 32% of patients who had received botulinum toxin were in symptomatic remission after a year compared to 70% after dilatation.7 A Cochrane review published in 2006 came to the conclusion that botulinum toxin injection was inferior to pneumatic dilatation at 6 months.10

Pneumatic dilatation

There is wide variation in the incidence of GORD (between 4% and 40%) after successful dilatation, which reflects method of assessment (symptomatic versus endoscopic), the number of repeat dilatations and the length of follow-up.13–15 In most patients, however, this can usually be controlled satisfactorily with a proton-pump inhibitor.

Cardiomyotomy

The two trials that claimed a difference are open to major criticism, not least because both were statistically underpowered. In the trial published by Csendes et al. in 1981,21 a superior result in favour of surgery in terms of relieving dysphagia needs to be balanced against a higher rate of reflux. In addition, the pneumatic dilatation was of very short duration and there is no doubt that the results in that arm of the study were inferior to those achieved subsequently with more modern balloons. A trial in Sweden with 51 patients included a routine partial fundoplication as part of the surgery and found more treatment failures in the dilatation arm. A pan-European study involving over 200 patients found no difference in success rates at 2 years (dilatation 86% and cardiomyotomy 90% success).23

Secondary achalasia

In South America, chronic infection with the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi causes Chagas’ disease, which has marked similarities to achalasia. The oesophagus becomes dilated (‘megaoesophagus’) and tortuous with a persistent retention oesophagitis due to fermentation of food residues. A severe cardiomyopathy is the main cause of death in these patients but some do require oesophagectomy.34

Pseudo-achalasia is an achalasia-like disorder that is usually produced by adenocarcinomas at the cardia or by any other tumour in the oesophageal wall at that level (e.g. gastrointestinal stromal tumours). While it seems attractive to suppose that the structural abnormalities related to these neoplasms must interfere with local neurotransmitters, pseudo-achalasia is sometimes also seen in patients with cancers outside the oesophagus (e.g. lung, pancreas), suggesting a paraneoplastic process.35

Diffuse oesophageal spasm

This is a rare condition of unknown cause characterised clinically by episodes of severe chest pain and/or dysphagia.36 The upper oesophagus covered by striated muscle is usually unaffected, in contrast to the lower two-thirds, where there is pronounced muscular thickening. Chest pain can be very severe and often occurs in isolation at night. Sometimes chest pain and dysphagia occur at the same time. Many patients undergo detailed assessment for cardiac causes of chest pain or reflux disease.

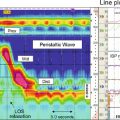

The diagnosis is rarely made by endoscopy or contrast radiology. Corkscrew oesophagus on a barium swallow is the exception rather than the rule. Diffuse oesophageal spasm is defined by conventional manometry as the presence of two or more non-peristaltic sequences in a series of 10 wet swallows, but high-resolution techniques suggest that this is inadequate (Table 16.1). In many patients, abnormal contractions are characterised by multipeaked waves of increased duration and amplitude37 (Fig. 16.2) exceeding 300 mmHg on conventional studies or 8000 mmHg • s • cm as defined by high-resolution pressure topography (hypercontractile or jackhammer oesophagus). It is evident that not all abnormal contractions produce a symptomatic event, but all symptomatic events are associated with abnormal manometric appearances.38

Figure 16.2 Diffuse oesophageal spasm. High-resolution manometry from a patient presenting with dysphagia and chest pain. The swallow is followed by simultaneous, repetitive contractions in the mid-distal smooth muscle oesophagus. LOS relaxation is preserved. Note that the sequential simultaneous contractions first in the middle and distal segments of the oesophagus and then LOS make it appear as if there is progressive peristalsis on the conventional line plots (dotted arrow). Repetitive contractions are seen clearly on both.

Oesophagogastric junction outflow obstruction and non-specific oesophageal motor disorders

Nutcracker oesophagus merely refers to high-amplitude contractions (> 180 mmHg) with normal peristalsis during standard manometry and undoubtedly some of these patients can be re-classified by high-resolution techniques. So-called ‘hypertensive LOS’ (on the basis of a resting pressure > 45 mmHg) used to be diagnosed when the sphincter was thought to still exhibit normal relaxation and there was normal peristalsis. The ability of high-resolution pressure topography to separate effects of the lower sphincter from the diaphragmatic crura has shed new light on this phenomenon, implying that in a proportion of such patients the true functional obstruction is at the diaphragm and not the sphincter, potentially related to the presence of a sliding hiatus hernia. Non-specific motor disorders cover a ragbag of manometric abnormalities that lie outside the normal ranges covered by conventional or high-resolution manometry. Many patients with reflux disease will have one or more of these abnormalities and treatment should be directed towards their reflux disease. Inevitably, most patients with a non-specific manometric abnormality have oesophageal symptoms, but correlation with these manometric abnormalities is poor. Great care should be exercised in labelling patients with a manometric diagnosis.40 There is virtually no evidence that any of these abnormalities responds to a specific treatment.

Oesophageal motor disturbances and autoimmune disease

References

1. Bredenoord, A.J., Fox, M., Kahrilas, P.J., et al, Chicago classification criteria of esophageal motility disorders defined in high resolution esophageal pressure topography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(Suppl. 1):57–65. 22248109

2. Pandolfino, J.E., Kwiatek, N.A., Nealis, T., et al, Achalasia: a new clinically relevant classification by high resolution manometry. Gastroenterology 2008; 135:1526–1533. 18722376

3. Podas, T., Eaden, J., Mayberry, M., et al, Achalasia: a critical review of epidemiological studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(12):2345–2347. 9860390

4. Mearin, F., Mourelle, M., Guarner, F., et al, Patients with achalasia lack nitric oxide synthase in the gastrooesophageal junction. Eur J Clin Invest 1993; 23:724–728. 7508398

5. Kraichely, R.E., Farrugia, G., Achalasia: physiology and etiopathogenesis. Dis Esophagus 2006; 19:213–223. 16866850

6. Pasricha, P.J., Ravich, W.J., Hendrix, T.R., et al, Intrasphincteric botulinum toxin for the treatment of achalasia. N Engl J Med 1995; 322:774–778. 7862180

7. Fishman, V.M., Parkman, H.P., Schiano, T.D., et al, Symptomatic improvement in achalasia after botulinum toxin injection into the lower oesophageal sphincter. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91:1724–1730. 8792688

8. Gordon, J.M., Eaker, E.Y., Prospective study of oesophageal botulinum toxin injection in high-risk achalasia patients. Am J Gastroenterol 1997; 92:1812–1817. 9382042

9. Vaezi, M.F., Richter, J.E., Wilcox, C.M., et al, Botulinum toxin versus pneumatic dilatation in the treatment of achalasia: a randomised trial. Gut 1999; 44:231–239. 9895383 A small study, with no CONSORT diagram to explain recruitment and randomisation, and no power calculation.

10. Leyden, J.E., Moss, A.C., MacMathuna, P., Endoscopic pneumatic dilatation versus botulinum toxin injection in the management of primary achalasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; CD005046. 17054234 A careful overview of the relative merits of the two techniques. Nothing has changed in the last few years.

11. Kadakia, S.C., Wong, R.K.H., Graded pneumatic dilatation using Rigiflex achalasia dilators in patients with primary oesophageal achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol 1993; 88:34–38. 8420271

12. Annese, V., Basciani, M., Perri, F., et al, Controlled trial of botulinum toxin injection versus placebo and pneumatic dilatation in achalasia. Gastroenterology 1996; 111:1418–1424. 8942719

13. Vela, M.F., Richter, J.E., Khandwala, F., et al, The long-term efficacy of pneumatic dilatation and Heller myotomy for the treatment of achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4:580–587. 16630776

14. Zerbib, F., Thetiot, V., Benajah, D.A., et al, Repeated pneumatic dilatations as long-term maintenance therapy for esophageal achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101:692–697. 16635216

15. Leeuwenburgh, I., Van Dekken, H., Scholten, P., et al, Oesophagitis is common in patients with achalasia after pneumatic dilatation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 23:1197–1203. 16611281

16. Richards, W.O., Torquati, A., Holzman, M.D., et al, Heller myotomy versus Heller myotomy with Dor fundoplication for achalasia: a prospective randomized double-blind clinical trial. Ann Surg 2004; 240:405–412. 15319712 A small study from a centre with a number of publications on achalasia. Compare this with their own results in earlier studies.

17. Sharp, K.W., Khaitan, L., Scholz, S., et al, 100 consecutive minimally invasive Heller myotomies: lessons learned. Ann Surg 2002; 235:631–638. 11981208

18. Costantini, M., Zaninotto, G., Guirolli, E., et al, The laparoscopic Heller–Dor operation remains an effective treatment for esophageal achalasia at a minimum 6-year follow-up. Surg Endosc 2005; 19:345–351. 15645326 The most useful recent article describing long-term outcomes, highlighting the paucity of data in relation to all achalasia treatments.

19. Bonavina, L., Incarbone, R., Reitano, M., et al, Does previous endoscopic treatment affect the outcome of laparoscopic Heller myotomy? Ann Chir 2000; 125:45–49. 10921184

20. Portale, G., Costantini, M., Rizzetto, C., et al, Long-term outcome of Heller–Dor surgery for esophageal achalasia: possible detrimental role of previous endoscopic treatment. J Gastrointest Surg 2005; 9:1332–1339. 16332491

21. Csendes, A., Velasco, N., Braghetto, J., et al, A prospective randomized study comparing forceful dilatation and oesophagomyotomy in patients with achalasia of the oesophagus. Gastroenterology 1981; 80:789–795. 7202950 An important study and clearly the first true comparison. It is inevitably open to criticism, mainly regarding the method of pneumatic dilatation. The late follow-up paper from the same group is worth reading.

22. Kostic, S., Kjellin, A., Ruth, M., et al, Pneumatic dilatation or laparoscopic cardiomyotomy in the management of newly diagnosed achalasia. Results of a randomised controlled trial. World J Surg 2007; 31:470–478. 17308851

23. Boeckxstaens, G.E., Annese, V., Bruley des Varannes S, et al. Pneumatic dilatation versus laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy for idiopathic achalasia. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1807–1816. 21561346 The first adequately powered and generalisable study, showing no important differences.

24. Urbach, D.R., Hansen, P.D., Khajanchee, Y.S., et al, A decision analysis of the optimal initial approach to achalasia: laparoscopic Heller myotomy with partial fundoplication, thoracoscopic Heller myotomy, pneumatic dilatation or botulinum toxin injection. J Gastrointest Surg 2001; 5:192–205. 11331483

25. O’Connor, J.B., Singer, M.E., Imperiale, T.F., et al, The cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci 2002; 47:1516–1525. 12141811

26. Kostic, S., Johnsson, E., Kjellin, A., et al, Health economic evaluation of therapeutic strategies in patients with idiopathic achalasia: results of a randomized trial comparing pneumatic dilatation with laparoscopic cardiomyotomy. Surg Endosc 2007; 21:1184–1189. 17514399

27. Karanicolas, P.J., Smith, S.E., Inculet, R.I., et al, The cost of laparoscopic myotomy versus pneumatic dilatation for esophageal achalasia. Surg Endosc 2007; 21:1198–1206. 17479318

28. Devaney, E.J., Lannettoni, M.D., Orringer, M.B., et al, Esophagectomy for achalasia: patient selection and clinical experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2001; 72:854–858. 11565670 A highly informative case series that highlights the problems faced in dealing with end-stage disease.

29. Meijssen, M.A., Tilanus, H.W., van Blankenstein, M., et al, Achalasia complicated by oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective study in 195 patients. Gut 1992; 33:155–158. 1541408

30. Aggestrup, S., Holm, J.C., Sorensen, H.R., Does achalasia predispose to cancer of the esophagus? Chest 1992; 102:1013–1016. 1395735

31. Streitz, J.M., Jr., Ellis, F.H., Jr., Gibb, S.P., et al, Achalasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the eosophagus: analysis of 241 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 1995; 59:1604–1609. 7771859

32. Sandler, R.S., Nyren, O., Ekbom, A., et al, The risk of esophageal cancer in patients with achalasia. A population-based study. JAMA 1995; 274:1359–1362. 7563560

33. Zendehdel, K., Nyren, O., Edberg, A., et al, Risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in achalasia patients, a retrospective cohort study in Sweden. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(1):57–61. 21212754

34. Pinotti, H.W., A new approach to the thoracic esophagus by the abdominal trans-diaphragmatic route. Langenbecks Arch Chir 1983; 359:229–235. 6855378

35. Portale, G., Costantini, M., Zaninotto, G., et al, Pseudoachalasia: not only esophago-gastric cancer. Dis Esophagus 2007; 20:168–172. 17439602

36. Osgood, H. A peculiar form of oesophagismus. Boston Med Surg J. 1889; 120:401–405.

37. Richter, J.E., Bradley, L.A., Castell, D.O., Esophageal chest pain: current controversies in pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. Ann Intern Med 1989; 110:66–78. 2642283

38. Barham, C.P., Gotley, D.C., Fowler, A., Diffuse oesophageal spasm: diagnosis by ambulatory 24 hour manometry. Gut 1997; 41:151–155. 9301491 The first study to characterise diffuse oesophageal spasm in this way. It emphasises the importance of manometric abnormality and symptom correlation.

39. Leconte, M., Douard, R., Gaudric, M., et al, Functional results after extended myotomy for diffuse oesophageal spasm. Br J Surg 2007; 94:1113–1118. 17497756

40. Hsi, J.J., O’Connor, M.K., Kang, Y.W., et al, Nonspecific motor disorder of the esophagus: a real disorder or a manometric curiosity? Gastroenterology 1993; 104:1281–1284. 8482442

41. Kaye, M.D., Oesophageal motor dysfunction in patients with diverticula of the mid-thoracic oesophagus. Thorax 1974; 29:666–672. 4217474

42. Di Marino, A.J., Cohen, S., Characteristics of lower esophageal sphincter function in symptomatic diffuse esophageal spasm. Gastroenterology 1974; 66:1–6. 4809495