CHAPTER 14 The male facelift

History

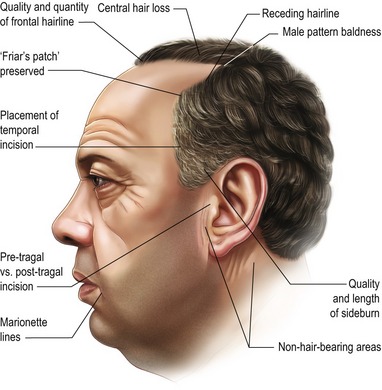

Facial rejuvenation in the male patient can be particularly challenging for a variety of plainly apparent reasons: men don’t wear makeup, they eschew any possibility of an over-operated appearance, and the hairline and beard cause many differences in terms of operative strategies (see Table 14.1). In a world that equates youthful appearance with fresh, new ideas, the patient population now encompasses men who want to stay busy in a very competitive environment rather than for vanity. They may be in business, acting, television, even politics. Growing social acceptability of aesthetic techniques has added to this demand.

The technical and aesthetic goals of the male facelift (Tables 14.2A and 14.2B) share similar principles as for the female: dissection in skin and sub-SMAS layers, repositioning of the SMAS and supra-SMAS fat to restore volume in a vertical vector, avoiding a lateral pull, and redraping of the skin in a natural way. It is, however, absolutely essential that the surgeon understands important differences between the male and female patient and also has a commanding knowledge of the male anatomy and techniques to achieve these goals in a naturally appearing way.

Table 14.2A General aesthetic goals for male facial rejuvenation

Table 14.2B Immediate surgical goals for male facial rejuvenation

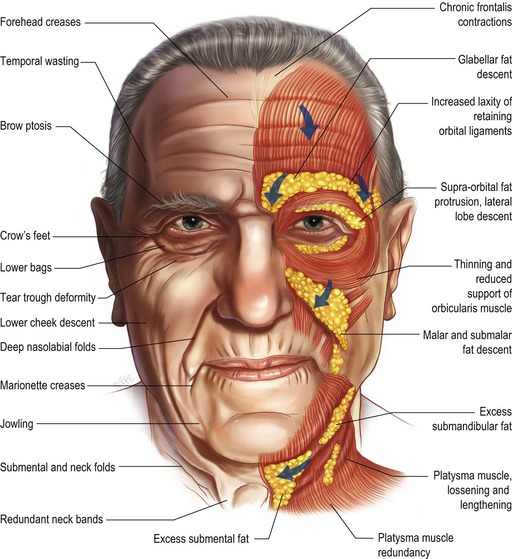

The process of facial aging represents a combination of gravitational effects, atrophy, and sun damage yielding the characteristic changes shown in Figs 14.1 and 14.2. This chapter will review the process of facial aging, the relevant surgical anatomy, and the common male facelift techniques.

Physical evaluation

Preoperative counseling

The classic “SIMON” patient described in the plastic surgery literature (see Table 14.3) should be avoided as well as patients with body dysmorphic disorder. These patients can be easily recognized, screened and referred for psychiatric evaluation.

Technical steps

Preoperative management

0.1–0.2 mg of clonidine is administered to the hypertensive patient at least 45 minutes prior to the procedure. Ten minutes before, the patient is also infused with local tumescent fluid (0.5% lidocaine, 1 : 200,000 epinephrine) bilaterally. These two steps will help blood pressure control intra- and postoperatively. It is especially important to maintain a dry intra-operative field as the hypervascularity of the male follicular skin contributes to the increased incidence of hematoma formation.

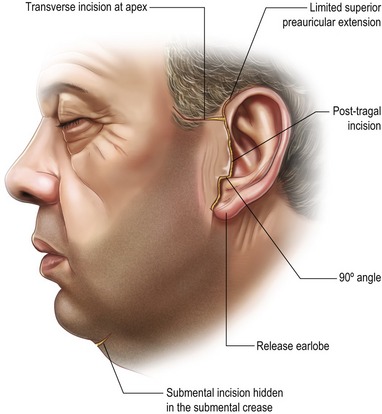

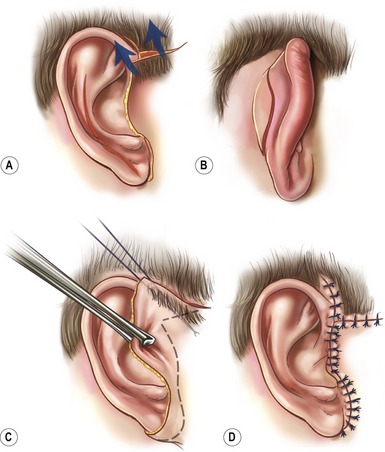

The incision options for the male facelift are illustrated in Fig. 14.3. The preauricular hairline incision chosen depends on the amount of skin laxity, skin quality, and previous incisions. The incision is initiated a short distance anterior and superior to the root of the helix in the temporal scalp, may extend transversely into the sideburn, and if necessary, sparingly follows the anterior temporal hairline (see Fig. 14.4). As discussed previously, the preauricular incision then proceeds caudally in the pre-tragal region if there is a natural skin crease and very little sun damage. The scalpel should bevel in line with the hair shaft. Alternatively, a post-tragal incision with defatting and follicular cauterization is performed. For the short-scar facelift, the incision passes beneath the earlobe and extends into the retroauricular sulcus staying 2 mm on the concha, so any scar migration that may occur will pull the scar no farther than into the sulcus. If there is severe laxity of the neck skin, the incision then traverses the hairless skin in the retroauricular region for 3–5 mm at a point which is superior enough in this region to be hidden if the patient opts for short hair. The final result should not be compromised simply to rigidly commit to a shorter retroauricular incision. If there is too much cervical laxity, the surgeon must extend the incision into the hair. Going into the retroauricular scalp with a sigmoid curve, instead of the occipital hairline incision, is preferred as men tend to retain their hair growth in this region and it allows the patient to have closely cropped hair without a visible incision.

Submental dissection and undermining

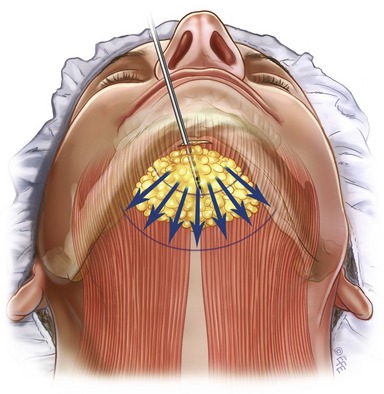

In patients with abundant excess skin in the submental region, a 1.5–2.5 cm submental incision is made and submental liposuction (see Fig. 14.5) and subcutaneous undermining is performed. In younger patients with minimal laxity or early aging, the incision is omitted and submental liposuction centrally or lateral undermining is performed via the inferior pole of the retroauricular incisions only. The author prefers to make the incision at the submental crease. Dissection is then performed retrograde to undermine the crease. Rarely, in patients in whom the crease is deep, the crease is completely excised. It is especially important to retain a cuff of subcutaneous fat at the incision to avoid deepening the submental crease.

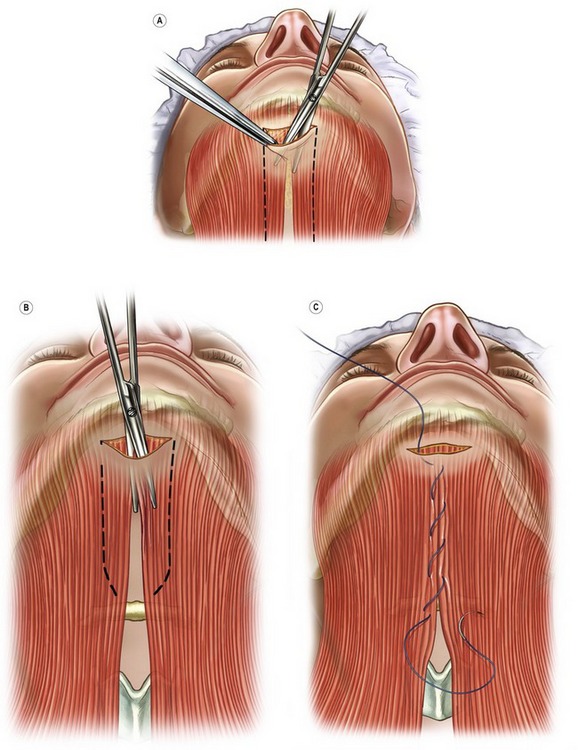

The platysma is defatted under direct vision and the anatomy of the medial borders of the platysma is identified (see Fig. 14.5). Subplatysmal fat may occasionally be directly resected. Submandibular gland resection should be avoided because of the increased risk of hematoma with this practice. Also, gland resection can result in a feminizing “popsicle on a stick” appearance of a skeletonized, over-operated neck. A midline plication of the platysmal muscles may be performed using buried 3-0 PDS sutures. A wedge of platysma may be excised bilaterally caudal to the plication to break the continuity of the platysmal bands (see Fig. 14.6).

SMAS/platysma flap

A SMAS imbrication alone may be preferred in cases of a secondary facelift or in cases of minimal laxity in a slender patient with a thin SMAS. The area to be imbricated should be initiated from 1 cm inferior to the earlobe and extend to 1 cm lateral and inferior to the lateral canthus (Figs 14.7D and Fig. 14.7E). The medial “dog-ear” from this imbrication will create an attractive rejuvenating malar fullness. It is of the utmost importance to ensure that this malar eminence is symmetrical.

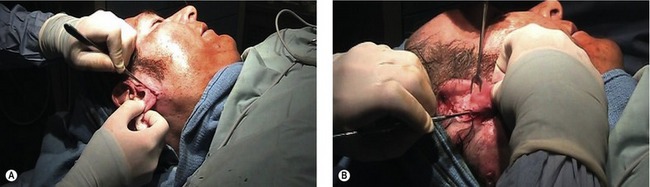

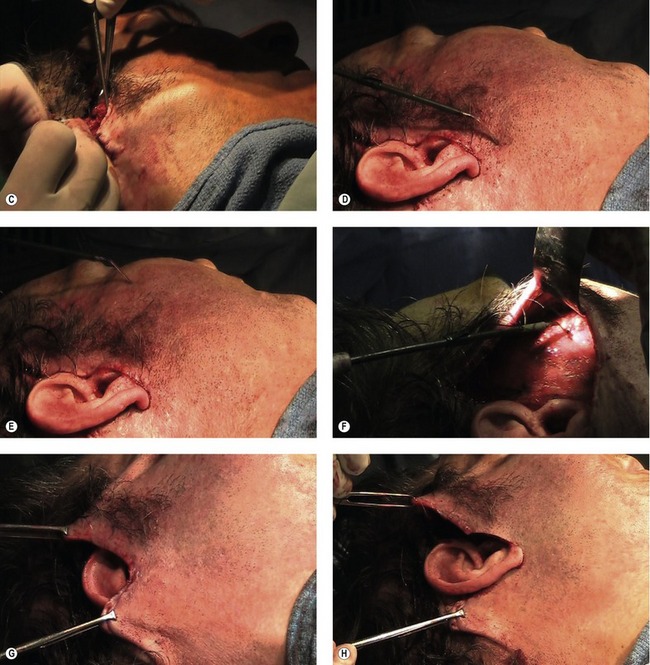

Fig. 14.7 Intraoperative photos of the male facelift in a 56-year-old man. A, The anterior incision is made, in this case pretragal incision was chosen. B, The retroauricular incision: staying high on the concha. C, Subcutaneous dissection with facelift scissors. D, Indicator demonstrates lateral endpoint of the lateral SMASectomy one centimeter inferior to the earlobe. E, Indicator demonstrates medial endpoint of the lateral SMASectomy one centimeter inferior and lateral to the lateral canthus. F, Indicator demonstrates lateral SMASectomy. G, Double Alice-clamp setting superiolateral vector. Emphasis should be on vertical lift to avoid a laterally pulled appearance. H, Trimming skin flap conservatively to inset lobe. I, Insetting midface flap anteriorly at the root of the helix. J, Posterior extent of short scar incision with redundant skin sparingly trimmed. Placement of #7 closed suction drain or open penrose drain posteriorly either through separate incision or within retroauricular closure. K, Insetting temporal flap with staples (“cheating” tissue in place and avoiding transverse excision of sideburn in this case). L, Insetting anterior flap with 5-0 nylon intertragal interrupted and running 6-0 nylon (5-0 plain gut running tragal suture is chosen for retrotragal incisions). Limited retroauricular gathering to close with a short incision which will remodel in postoperative phase. M, Anterior worm’s eye view demonstrating elevated malar repositioning, hollowing of lower midface, and improvement of neck and jawline on right side.

For the full SMAS dissection, a transverse incision is made in the SMAS at the level of the infraorbital rim, above the zygomatic arch. An intersecting vertical incision is made in the SMAS in the preauricular region and extended along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The SMAS and platysma muscle are elevated in continuity and advanced beyond the anterior border of the parotid gland resulting in a significant release and subsequent elevation of the midface structures. The SMAS is rotated in a cephaloposterior direction; the excess is resected, and the flap is sutured to the temporal fascia. A second set of sutures are placed in the platysma muscle which is tightened below the angle of the mandible and sutured to the fascia of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. A tongue of excess SMAS may be transposed behind the ear to reinforce the platysmal tightening. Additional sutures are then placed along the entire suture line to reinforce this maneuver.

Complications

Hematomas

The etiology of hematomas is multifactorial, but correlates most closely with perioperative hypertension, with hematomas occurring 2.6 times more frequently in hypertensive patients than those with normal blood pressures. Any medications or substances (aspirin-containing medications, herbal teas and other agents) which affect the coagulation cascade must be discontinued 2 weeks before the procedure.

Hyperpigmentation

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• During SMAS dissection, the smart surgeon must have the utmost respect for the glistening parotid fascia to avoid facial nerve and parotid duct injury.

• Generally minimize incision length without compromising the patient’s result.

• Minimizing dissection when possible will lower the rate of hematoma formation when dealing with the highly vascularized male skin.

• Don’t go for the last wrinkle and tell this to the patient preoperatively. One or two lines give a natural character. Avoid or educate the patient who wants too much.

• When dissecting the submental subcutaneous area, leave a cuff of subcutaneous fat near the incision to avoid the tell-tale incision step-off postoperatively.

• Bevel the scalpel parallel to the hair shaft in all incisions to prevent alopecia.

• Clonidine patch or hydralazine is the surgeon’s friend in the postoperative hypertensive patient.

Pitfalls

• Avoid over-retracting the skin flap during skin and SMAS dissection to prevent undue trauma which inevitably results in sloughing postoperatively.

• Knowledge of facial nerve anatomy is an absolute must and the junior surgeon should be familiar or review the danger points to avoid injury.

• When using the Bovie for hemostasis, say: “nerve” or “flap” so the assistant can monitor the face, responding with “twitch” or “burn” (denoting nerve twitch or thermal injury to the flap, respectively). This will prevent the two major Bovie injuries.

• Don’t make the submental incision too long to avoid visible scars after skin flaps are redraped cephaloposteriorly.

• Focus on a lifting vector, erring on the vertical rather than the lateral to avoid a “lateral pull” appearance.

• Don’t rely on a single running dissolvable suture for the retroauricular closure. Placing two additional interrupted sutures will save a 3 a.m. phone call and a wide scar postoperatively.

Summary of steps

1. Administer clonidine, 0.1–0.2 mg, preoperatively.

2. Inject with 0.5% lidocaine, 1 : 200,000 epinephrine.

4. Submental liposuction of central fat.

5. Suture platysma in midline for vertical bands, as necessary.

6. 10-blade and Adson’s forceps with teeth to develop subcutaneous plane. Pre- or retrotragal incision or preauricular incision (see Fig. 14.7A).

7. Thumb in thimble hook with third and fourth finger controlling tension.

8. Incise behind ear, staying 2 mm on the concha (see Fig. 14.7B); carry into the scalp only if necessary.

10. Finger-assisted malar elevation (FAME, Aston). Sweep on periosteum from orbital rim to free all of midface structures for deep plane composite of skin, muscle, and fat.

11. Assistant skinhooks ear forward. Use double hook, ribbon retractor to dissect with 10-blade behind the ear.

12. Return to anterior scissor dissection in the subcutaneous plane with two single skin hooks in contralateral hand (see Fig. 14.7C). Flap thickness determined by response of scissors through tissues and contralateral hand tactile pressure.

13. Continue scissor dissection down into the neck. Assistant retracts ear.

14. Identify spinal accessory nerve “peeking” out from lateral boarder of SCM in loose aereolar fascia.

15. Assistant gently applies two fingers on flap while surgeon gently lifts with lighted retractor.

16. Preserve position of sideburn. Incise flap at the root of the helix. Assistant stabilizes the transverse incision with two staples.

17. SMAS dissection: stay sub-SMAS; respect glistening parotid fascia to avoid parotid duct and facial nerve injury.

18. SMAS treatment possibilities: (securing mobile to immobile SMAS; consider barbed suture) (see Fig. 14.7D–F):

19. Finish contour of jawline with the suction-vacuum for polished effect.

21. Use two Alice clamps to set skin flap rotation (see Fig. 14.7G). Set posterior flap with 3-0 plain gut suture.

22. Excise redundant sigmoid of occipital scalp incision and re-approximate with staples; minimal hemostasis of scalp skin edge necessary in this area.

23. Trim non-hair bearing area of the skin in front of the ear.

24. Trim conservatively around the lobe (see Fig. 14.7H) and set with a tri-stitch involving lobe skin, flap skin, and mastoid fascia with no tension, 5-0 nylon stitch at lobe then run a 6-0 nylon cephalad.

25. Stabilize flap anteriorly at root of the helix (see Fig. 14.7I) with figure-of-eight suture.

26. Trim retroauricular (see Fig. 14.7J) and run with 5-0 plain cat-gut with good bites.

27. Assistant pulls flap laterally as Burrow’s triangle in sideburn is resected and staple superior temporal hair-bearing area (see Fig. 14.7K).

28. Place drain exiting through separate stab or at superior pole of retroauricular incision.

29. Defat and cauterize beard follicles in the generous neo-tragal area (the excess will retract).

30. Thin tragus and close with 5-0 fast-absorbing cat gut suture.

31. Set the intertragal notch with 5-0 nylon.

32. Close remainder with 6-0 nylon, full thickness and run superiorly (see Fig. 14.7L).

33. Observe differences between preoperative and postoperative sides (see Fig. 14.7M).

Aston SJ. FAME dissection in rhytidectomy. Personal Communication, 3 March 2008.

Aston SJ. Platysma muscle in rhytidoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 1979;3(6):529–539.

Baker D, Conley J. Avoiding facial nerve injuries in rhytidectomy: Anatomic variations and pitfalls. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;64:781.

Baker DC, Aston SJ, Guy CL, Rees TD. The male rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;4:514.

Baker DC. Complications of cervicofacial rhytidectomy. Clin Plast Surg. 1983;10:543.

Connell BF. Eyebrow, face, and neck lifts for males. Clin Plast Surg. 1978;5(1):15–28.

Cremone J, Courtiss EH, Baker JL, Jr. Male rhytidectomy incisions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;71(3):423–426.

Ellenbogen R. Transcoronal eyebrow lift with concomitant upper blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;71:490.

Furnas D. The retaining ligaments of the cheek. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:11.

Gosain A, et al. Surgical anatomy of the SMAS: A reinvestigation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1254.

LaTrent G. Atlas of Aesthetic Face & Neck Surgery. Philadelphia PA. Saunders. 2004.

Mitz V, Peyronie M. The superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:80.

Rees TD, Aston SJ. Complications of rhytidectomy. Clin Plast Surg. 1978;5:1.

Stuzin J, et al. Anatomy of the frontal branch of the facial nerve: The significance of the temporal fat pad. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:265.