Chapter 1 The lumbar vertebrae

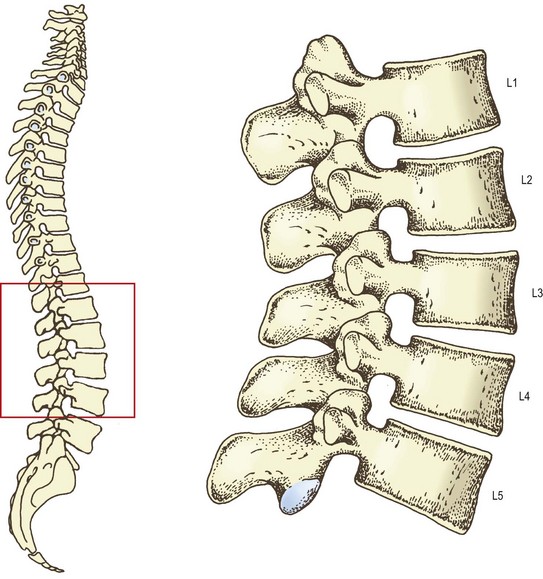

The lumbar vertebral column consists of five separate vertebrae, which are named according to their location in the intact column. From above downwards they are named as the first, second, third, fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae (Fig. 1.1). Although there are certain features that typify each lumbar vertebra, and enable each to be individually identified and numbered, at an early stage of study it is not necessary for students to be able to do so. Indeed, to learn to do so would be impractical, burdensome and educationally unsound. Many of the distinguishing features are better appreciated and more easily understood once the whole structure of the lumbar vertebral column and its mechanics have been studied. To this end, a description of the features of individual lumbar vertebrae is provided in the Appendix and it is recommended that this be studied after Chapter 7.

A typical lumbar vertebra

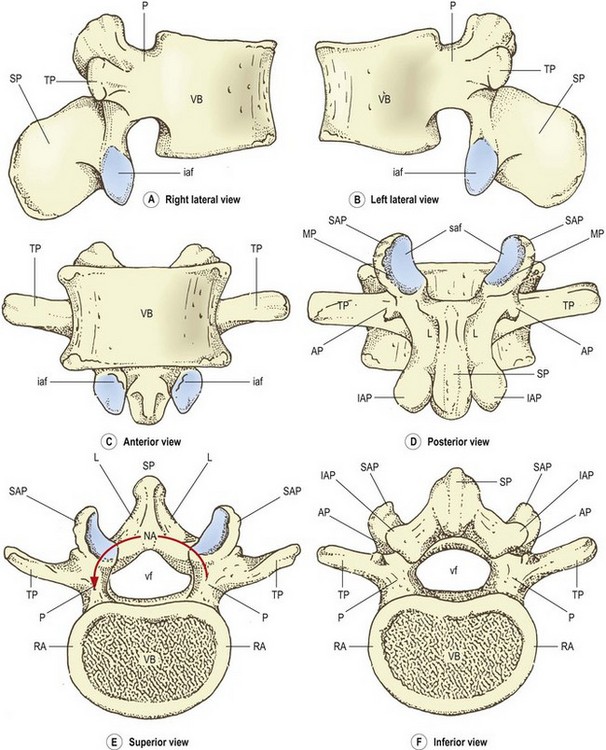

The lumbar vertebrae are irregular bones consisting of various named parts (Fig. 1.2). The anterior part of each vertebra is a large block of bone called the vertebral body. The vertebral body is more or less box shaped, with essentially flat top and bottom surfaces, and slightly concave anterior and lateral surfaces. Viewed from above or below the vertebral body has a curved perimeter that is more or less kidney shaped. The posterior surface of the body is essentially flat but is obscured from thorough inspection by the posterior elements of the vertebra.

The greater part of the top and bottom surfaces of each vertebral body is smooth and perforated by tiny holes. However, the perimeter of each surface is marked by a narrow rim of smoother, less perforated bone, which is slightly raised from the surface. This rim represents the fused ring apophysis, which is a secondary ossification centre of the vertebral body (see Ch. 12).

The posterior surface of the vertebral body is marked by one or more large holes known as the nutrient foramina. These foramina transmit the nutrient arteries of the vertebral body and the basivertebral veins (see Ch. 11). The anterolateral surfaces of the vertebral body are marked by similar but smaller foramina which transmit additional intra-osseous arteries.

Projecting from the back of the vertebral body are two stout pillars of bone. Each of these is called a pedicle. The pedicles attach to the upper part of the back of the vertebral body; this is one feature that allows the superior and inferior aspects of the vertebral body to be identified. To orientate a vertebra correctly, view it from the side. That end of the posterior surface of the body to which the pedicles are more closely attached is the superior end (Fig. 1.2A, B).

The word ‘pedicle’ is derived from the Latin pediculus meaning little foot; the reason for this nomenclature is apparent when the vertebra is viewed from above (Fig. 1.2E). It can be seen that attached to the back of the vertebral body is an arch of bone, the neural arch, so called because it surrounds the neural elements that pass through the vertebral column. The neural arch has several parts and several projections but the pedicles are those parts that look like short legs with which it appears to ‘stand’ on the back of the vertebral body (see Fig. 1.2E), hence the derivation from the Latin.

The full extent of the laminae is seen in a posterior view of the vertebra (Fig. 1.2D). Each lamina has slightly irregular and perhaps sharp superior edges but its lateral edge is rounded and smooth. There is no medial edge of each lamina because the two laminae blend in the midline. Similarly, there is no superior lateral corner of the lamina because in this direction the lamina blends with the pedicle on that side. The inferolateral corner and inferior border of each lamina are extended and enlarged into a specialised mass of bone called the inferior articular process. A similar mass of bone extends upwards from the junction of the lamina with the pedicle, to form the superior articular process.

Extending laterally from the junction of the pedicle and the lamina, on each side, is a flat, rectangular bar of bone called the transverse process, so named because of its transverse orientation. Near its attachment to the pedicle, each transverse process bears on its posterior surface a small, irregular bony prominence called the accessory process. Accessory processes vary in form and size from a simple bump on the back of the transverse process to a more pronounced mass of bone, or a definitive pointed projection of variable length.1,2 Regardless of its actual form, the accessory process is identifiable as the only bony projection from the back of the proximal end of the transverse process. It is most evident if the vertebra is viewed from behind and from below (Fig. 1.2D, F).

Apart from providing this aid in orientating a lumbar vertebra, these notches have no intrinsic significance and have not been given a formal name. However, when consecutive lumbar vertebrae are articulated (see Fig. 1.7), the superior and inferior notches face one another and form most of what is known as the intervertebral foramen, whose anatomy is described in further detail in Chapter 5.

Particular features

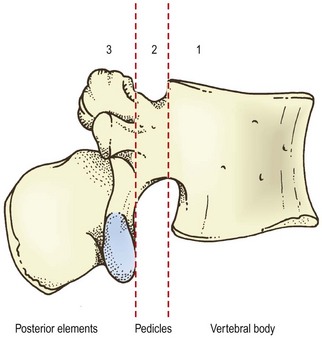

Conceptually, a lumbar vertebra may be divided into three functional components (Fig. 1.3). These are the vertebral body, the pedicles and the posterior elements consisting of the laminae and their processes. Each of these components subserves a unique function but each contributes to the integrated function of the whole vertebra.

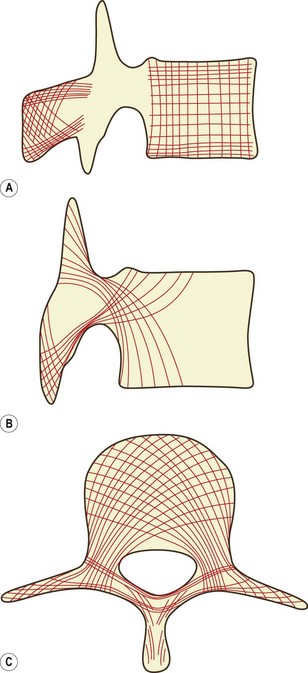

Vertebral body

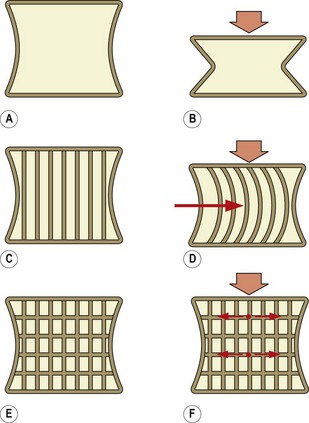

With just an outer layer of cortical bone, a vertebral body would be merely a shell (Fig. 1.4A). This shell is not strong enough to sustain longitudinal compression and would collapse like a cardboard box (Fig. 1.4B). It needs to be reinforced. This can be achieved by introducing some vertical struts between the superior and inferior surfaces (Fig. 1.4C). A strut acts like a solid but narrow block of bone and, provided it is kept straight, it can sustain immense longitudinal loads. The problem with a strut, however, is that it tends to bend or bow when subjected to a longitudinal force. Nevertheless, a box with vertical struts, even if they bend, is still somewhat stronger than an empty box (Fig. 1.4D). The load-bearing capacity of a vertical strut can be preserved, however, if it is prevented from bowing. By introducing a series of cross-beams, connecting the struts, the strength of a box can be further enhanced (Fig. 1.4E). Now, when a load is applied, the cross-beams hold the struts in place, preventing them from deforming and preventing the box from collapsing (Fig. 1.4F).

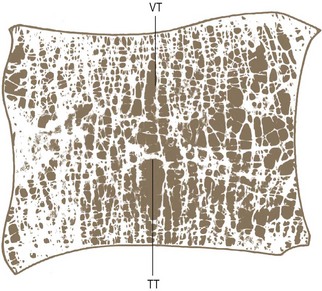

The internal architecture of the vertebral body follows this same design. The struts and cross-beams are formed by thin rods of bone, respectively called vertical and transverse trabeculae (Fig. 1.5). The trabeculae endow the vertebral body with weight-bearing strength and resilience. Any applied load is first borne by the vertical trabeculae, and when these attempt to bow they are restrained from doing so by the horizontal trabeculae. Consequently, the load is sustained by a combination of vertical pressure and transverse tension in the trabeculae. It is the transfer of load from vertical pressure to transverse tension that endows the vertebra with resilience. The advantage of this design is that a strong but lightweight load-bearing structure is constructed with the minimum use of material (bone).

A further benefit is that the space between the trabeculae can be profitably used as convenient channels for the blood supply and venous drainage of the vertebral body, and under certain conditions as an accessory site for haemopoiesis (making blood cells). Indeed, the presence of blood in the intertrabecular spaces acts as a further useful element for transmitting the loads of weight-bearing and absorbing force.3 When filled with blood, the trabeculated cavity of the vertebral body appears like a sponge, and for this reason it is sometimes referred to as the vertebral spongiosa.

Posterior elements

The posterior elements of a vertebra are the laminae, the articular processes and the spinous processes (see Fig. 1.3). The transverse processes are not customarily regarded as part of the posterior elements because they have a slightly different embryological origin (see Ch. 12), but for present purposes they can be considered together with them.

The spinous, transverse, accessory and mamillary processes provide areas for muscle attachments. Moreover, the longer processes (the transverse and spinous processes) form substantial levers, which enhance the action of the muscles that attach to them. The details of the attachments of muscles are described in Chapter 9 but it is worth noting at this stage that every muscle that acts on the lumbar vertebral column is attached somewhere on the posterior elements. Only the crura of the diaphragm and parts of the psoas muscles attach to the vertebral bodies but these muscles have no primary action on the lumbar vertebrae. Every other muscle attaches to either the transverse, spinous, accessory or mamillary processes or laminae. This emphasises how all the muscular forces acting on a vertebra are delivered first to the posterior elements.

That part of the lamina that intervenes between the superior and inferior articular process on each side is given a special name, the pars interarticularis, meaning ‘interarticular part’. The pars interarticularis runs obliquely from the lateral border of the lamina to its upper border. The biomechanical significance of the pars interarticularis is that it lies at the junction of the vertically orientated lamina and the horizontally projecting pedicle. It is therefore subjected to considerable bending forces as the forces transmitted by the lamina undergo a change of direction into the pedicle. To withstand these forces, the cortical bone in the pars interarticularis is generally thicker than anywhere else in the lamina.4 However, in some individuals the cortical bone is insufficiently thick to withstand excessive or sudden forces applied to the pars interarticularis,5 and such individuals are susceptible to fatigue fractures, or stress fractures to the pars interarticularis.5–7

Pedicles

The pedicles transmit both tension and bending forces. If a vertebral body slides forwards, the inferior articular processes of that vertebra will lock against the superior articular processes of the next lower vertebra and resist the slide. This resistance is transmitted to the vertebral body as tension along the pedicles. Bending forces are exerted by the muscles attached to the posterior elements. Conspicuously (see Ch. 9), all the muscles that act on a lumbar vertebra pull downwards. Therefore, muscular action is transmitted to the vertebral body through the pedicles, which act as levers and thereby are subjected to a certain amount of bending.

Internal structure

The trabecular structure of the vertebral body (Fig. 1.6A) extends into the posterior elements. Bundles of trabeculae sweep out of the vertebral body, through the pedicles, and into the articular processes, laminae and transverse processes. They reinforce these processes like internal buttresses, and are orientated to resist the forces and deformations that the processes habitually sustain.8 From the superior and inferior surfaces of the vertebral body, longitudinal trabeculae sweep into the inferior and articular processes (Fig. 1.6B). From opposite sides of the vertebral body, horizontal trabeculae sweep into the laminae and transverse processes (Fig. 1.6C). Within each process the extrinsic trabeculae from the vertebral body intersect with intrinsic trabeculae from the opposite surface of the process. The trabeculae of the spinous process are difficult to discern in detail, but seem to be anchored in the lamina and along the borders of the process.8

The intervertebral joints

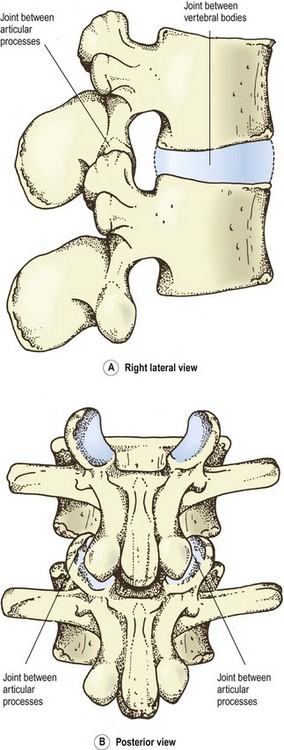

When any two consecutive lumbar vertebrae are articulated, they form three joints. One is formed between the two vertebral bodies. The other two are formed by the articulation of the superior articular process of one vertebra with the inferior articular processes of the vertebra above (Fig. 1.7). The nomenclature of these joints is varied, irregular and confusing.

The joints between the articular processes have an ‘official’ name. Each is known as a zygapophysial joint.9 Individual zygapophysial joints can be specified by using the adjectives ‘left’ or ‘right’ and the numbers of the vertebrae involved in the formation of the joint. For example, the left L3–4 zygapophysial joint refers to the joint on the left, formed between the third and fourth lumbar vertebrae.

Because the zygapophysial joints are located posteriorly, they are also known as the posterior intervertebral joints. This nomenclature implies that the joint between the vertebral bodies is known as the anterior intervertebral joint (Table 1.1) but this latter term is rarely, if ever, used. In fact, there is no formal name for the joint between the vertebral bodies, and difficulties arise if one seeks to refer to this joint. The term ‘interbody joint’ is descriptive and usable but carries no formal endorsement and is not conventional. The term ‘anterior intervertebral joint’ is equally descriptive but is too unwieldy for convenient usage.

Table 1.1 Systematic nomenclature of the intervertebral joints

| Joints between articular process | Joints between vertebral bodies |

|---|---|

| Zygapophysial joints | (No equivalent term) |

| (No equivalent term) | Interbody joints |

| Posterior intervertebral joints | Anterior intervertebral joints |

| Intervertebral diarthroses | Intervertebral amphiarthroses or intervertebral symphyses |

The only formal technical term for the joints between the vertebral bodies is the classification to which the joints belong. These joints are symphyses, and so can be called intervertebral symphyses9 or intervertebral amphiarthroses, but again these are unwieldy terms. Moreover, if this system of nomenclature were adopted, to maintain consistency the zygapophysial joints would have to be known as the intervertebral diarthroses (see Table 1.1), which would compound the complexity of nomenclature of the intervertebral joints.

Spelling

Some editors of journals and books have deferred to dictionaries that spell the word ‘zygapophysial’ as ‘zygapophyseal’. It has been argued that this fashion is not consistent with the derivation of the word.10

The English word is derived from the singular: zygapophysis. Consequently the adjective ‘zygapophysial’ is also derived from the singular and is spelled with an ‘i’. This is the interpretation adopted by the International Anatomical Nomenclature Committee in the latest edition of the Nomina Anatomica.9

1 Le Double AF. Traité des Variations de la Colonne Vertébral de l’Homme. Paris: Vigot; 1912. 271–274

2 Louyot P. Propos sur le tubercle accessoire de l’apophyse costiforme lombaire. J Radiol Electrol. 1976;57:905-906.

3 White AA, Panjabi MM. Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1978.

4 Krenz J, Troup JDG. The structure of the pars interarticularis of the lower lumbar vertebrae and its relation to the etiology of spondylolysis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1973;55B:735-741.

5 Cyron BM, Hutton WC. Variations in the amount and distribution of cortical bone across the partes interarticulares of L5. A predisposing factor in spondylolysis? Spine. 1979;4:163-167.

6 Hutton WC, Stott JRR, Cyron BM. Is spondylolysis a fatigue fracture? Spine. 1977;2:202-209.

7 Troup JDG. The etiology of spondylolysis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1977;8:57-64.

8 Gallois M, Japiot M. Architecture intérieure des vertébrés (statique et physiologie de la colonne vertébrale). Rev Chirurgie. 1925;63:687-708.

9 International Anatomical Nomenclature Committee. Nomina Anatomica, 6th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1989.

10 Bogduk N. On the spelling of zygapophysial and of anulus. Spine. 1994;19:1771.