18 The lowest four cranial nerves

Comments on the last four cranial nerves in ascending order:

Hypoglossal Nerve

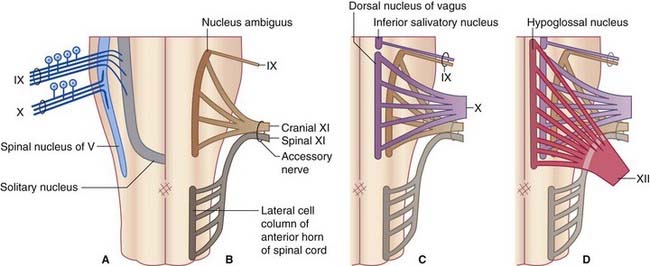

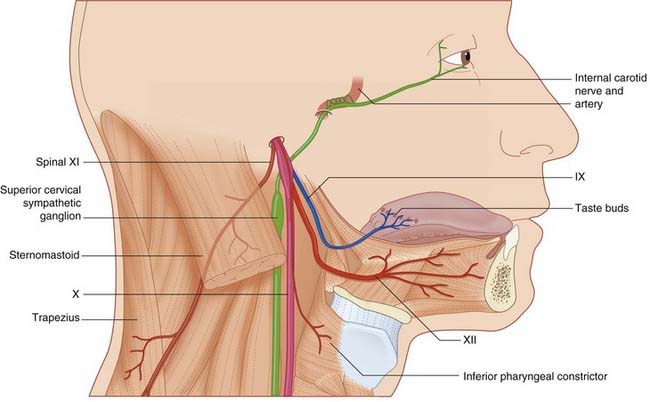

The hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII) contains somatic efferent fibers for the supply of the extrinsic and intrinsic muscles of the tongue, except palatoglossus (supplied by the cranial accessory nerve). Its nucleus lies close to the midline in the floor of the fourth ventricle and extends almost the full length of the medulla (Figure 18.1). The nerve emerges as a series of rootlets in the interval between the pyramid and the olive. It crosses the subarachnoid space and leaves the skull through the hypoglossal canal. Just below the skull, it lies close to the vagus and spinal accessory nerves (Figure 18.2). It descends on the carotid sheath to the level of the angle of the mandible, then passes forward on the surface of the hyoglossus muscle where it gives off its terminal branches.

Supranuclear supply to the hypoglossal nucleus

Supranuclear, nuclear, and infranuclear lesions of the hypoglossal nerve are described together with lesions of the accessory nerve (see Clinical Panels 18.1–18.3).

Clinical Panel 18.1 Supranuclear lesions of the lowest four cranial nerves

Effects of unilateral supranuclear lesions

Clinical Panel 18.2 Nuclear lesions of the X, XI, and XII cranial nerves

Lesions of the hypoglossal nucleus and nucleus ambiguus occur together in progressive bulbar palsy, a variant of progressive muscular atrophy (Ch. 16) in which the cranial motor nuclei of the pons and medulla are attacked at the outset. The patient quickly becomes distressed by a multitude of problems: difficulty in chewing and articulation (mandibular and facial nerve nuclei) and difficulty in swallowing and phonation (hypoglossal and cranial accessory nuclei).

Unilateral lesions at nuclear level may be caused by occlusion of the vertebral artery or of one of its branches (see Clinical Panel 19.2). The distribution of motor weakness is the same as for infranuclear lesions (see Clinical Panel 18.3).

Clinical Panel 18.3 Infranuclear lesions of the lowest four cranial nerves

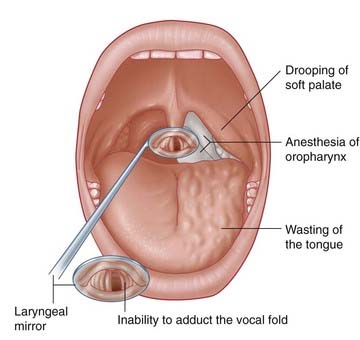

Symptoms

Signs (Figure CP 18.3.1)

A jugular foramen syndrome may also be caused by invasion of the jugular foramen from above, for instance by a tumor extending from the cerebellopontine angle (Ch. 20). In this case, the sympathetic and spinal accessory nerves will be out of reach, and unaffected.

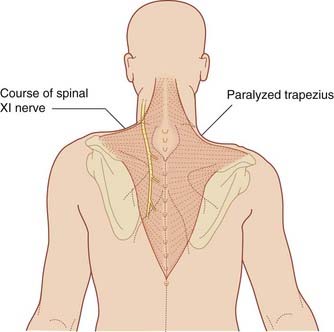

Isolated lesion of the spinal accessory nerve

The surface marking for the spinal accessory nerve in the posterior triangle of the neck is a line drawn from the posterior border of the sternomastoid one-third of the way down to the anterior border of the trapezius two-thirds of the way down. It may be injured in this part of its course by a stab wound, or during a surgical procedure for removal of cancerous lymph nodes. The trapezius is selectively paralyzed, whereupon the scapula and clavicle sag noticeably because trapezius normally helps to carry the upper limb. Shrugging of the shoulder is weakened because the levator scapulae must work alone. Progressive atrophy of the muscle leads to characteristic scalloping of the contour of the neck (Figure CP 18.3.2)

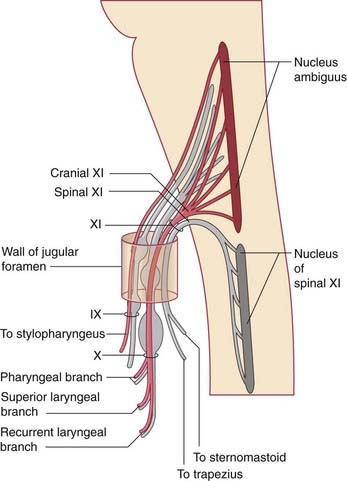

Spinal Accessory Nerve

The nerve runs upward in the subarachnoid space, behind the denticulate ligament. It enters the cranial cavity through the foramen magnum and leaves it again through the jugular foramen. While in the jugular foramen, it shares a dural sheath with the cranial accessory nerve, but there is no exchange of fibers (Figure 18.3). Upon leaving the cranium, it crosses the transverse process of the atlas and enters the sternomastoid muscle, in company with twigs from roots C2 and C3 of the cervical plexus. It emerges from the posterior border of the sternomastoid and crosses the posterior triangle of the neck to reach the trapezius. It pierces the trapezius in company with twigs from roots C3 and C4 of the cervical plexus. In the posterior triangle, the nerve is vulnerable, being embedded in prevertebral fascia and covered only by investing cervical fascia and skin.

Glossopharyngeal, Vagus, and Cranial Accessory Nerves

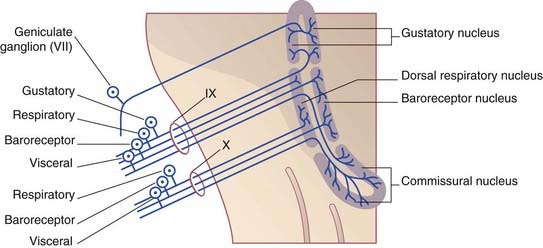

Anatomically, the nucleus is divisible into eight parts. Functionally, four regions have been clarified (Figure 18.4):

Glossopharyngeal nerve

Immediately below the skull, the glossopharyngeal is in the company of three other nerves (Figure 18.2): the vagus, the spinal accessory, and the internal carotid (sympathetic) branch of the superior cervical ganglion. Together with the stylopharyngeus, it slips between the superior and middle constrictor muscles to reach the mucous membrane of the oropharynx.

Functional divisions and branches

Note: the important carotid baroreceptor reflex is described in Chapter 24.

Note: carotid chemoreceptor reflex arcs are described in Chapter 24.

Vagus and cranial accessory nerves

The vagus is the main parasympathetic nerve. Its preganglionic component has a huge territory which includes the heart, the lungs, and the alimentary tract from esophagus through transverse colon (Ch. 10). At the same time, the vagus is the largest visceral afferent nerve; afferents outnumber parasympathetic motor fibers by four to one. Overall, the vagus contains the same seven fiber classes as the glossopharyngeal, and they will be listed in the same order.

The rootlets of the vagus and cranial accessory nerves are in series with the glossopharyngeal, and the three nerves travel together into the jugular foramen. At this point, the cranial accessory nerve shares a dural sheath with the spinal accessory, but there is no exchange of fibers (Figure 18.3). Just below the foramen, the cranial accessory is incorporated into the vagus. The vagus itself shows a small, jugular (superior) and a large, nodose (inferior) ganglion; both are sensory.

Functional divisions and branches

Andresen MC. Nucleus tractus solitarii – gateway to neural circulatory control. Ann Rev Physiol. 1994;56:93-117.

Eman AB, Kejner AE, Hogikyan ND, Feldman EL. Disorders IX and X. Semin Neurol. 2009;29:85-92.

FitzGerald MJT, Sachithanandan SR. The structure and source of lingual proprioceptors in the monkey. J Anat. 1979;128:523-552.

FitzGerald MJT, Comerford PT, Tuffery AR. Sources of innervation of the neuromuscular spindles in sternomastoid and trapezius. J Anat. 1982;144:184-190.

Lin HC, Barkhaus PE. Cranial nerve XII: the hypoglossal nerve. Semin neurol. 2009;29:45-52.

Massey EW. Spinal accessory nerve lesions. Semin Neurol. 2009;29:82-84.

Mtui EP, Anwar M, Reis DJ, Ruggiero DA. Medullary visceral reflex circuits: local afferents to nucleus tractus solitarii synthesize catecholamines and project to thoracic spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1995;351:5-26.

Ryan S, Blyth P, Duggan N, Wild M, Al-Ali S. Is the cranial accessory nerve really a portion of the accessory nerve? Anatomy of the cranial nerves in the jugular foramen. Anat Sci Int. 2007;82:1-7.

Thompson PD, Thickbroom GW, Mastaglia FL. Corticomotor representation of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Brain. 1997;120:245-255.