Chapter 27 The low-birthweight infant

DEFINITION OF LOW BIRTHWEIGHT

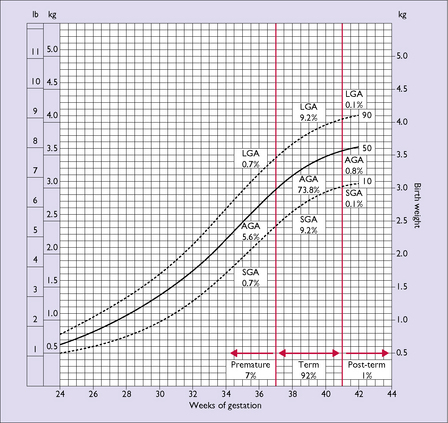

Although the rate of prematurity varies between communities, a common rate in developed countries is 7%, (and that of post-maturity up to 1%). The relation between growth and gestation is illustrated in Figure 27.1, including approximate percentages of the various combinations of gestation and growth relative to the normal parameters. Note that by these definitions less than 75% of babies are born of ‘normal’ gestation and weight. Note also that some LBW infants may be both premature and IUGR.

Fig. 27.1 Birthweight distribution versus gestation period. Dotted lines show the 10th and 90th centiles.

The growth chart illustrated in Figure 27.1 is from an Australian community. It is not necessarily applicable to all communities because of different genetic growth potentials; for instance the birthweights in a population of some Pacific Island groups would show higher growth centiles and some Indian populations would show lower centiles.

CAUSES OF LOW BIRTHWEIGHT

Causes and prevention of prematurity are discussed in Chapter 19, with a summary of causes given in Table 19.1.

The intra-uterine growth of the fetus depends on its inherited growth potential and the effectiveness of the support to its growth provided by the uteroplacental environment. The latter is affected by the presence or absence of maternal disease. The causes of IUGR can be classified according to maternal, placental and fetal causes, and are outlined in Box 27.1. In many cases no precise factor has been identified.

PROBLEMS OF PREMATURE AND GROWTH-RESTRICTED INFANTS

MANAGEMENT OF PREMATURE AND GROWTH-RESTRICTED INFANTS

The care of these infants should be conducted by a paediatrician with the resources available in a neonatal special care nursery (SCN – often called a special care baby unit – SCBU). Most VLBW infants and all ELBW require the care of a specialist neonatal multidisciplinary team in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). As mentioned in Chapter 19, a woman who goes into labour before the 36th week of pregnancy should, if possible, be transferred to a hospital with an SCN. If delivery is required before the completion of 32 weeks (in some regions this may be a higher gestation) all attempts should be made to transfer the mother for delivery at a hospital with an NICU.

Key points in the management include:

MORTALITY AND MORBIDITY OF LOW-BIRTHWEIGHT INFANTS

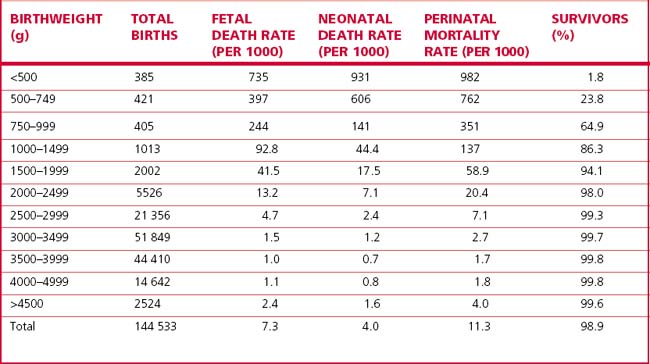

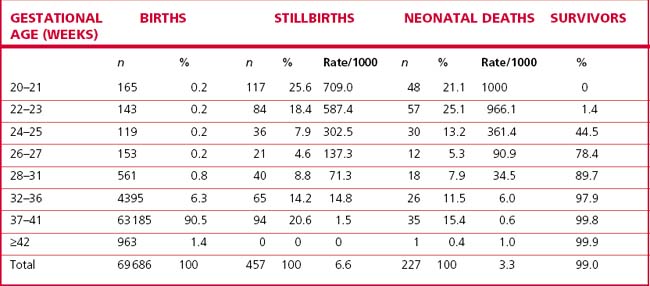

Low-birthweight infants contribute 70% of early neonatal deaths; the smaller and less mature the infant, the less its chance of survival (Table 27.1). The survival rates depend on the place of birth. Few infants of less than 24 weeks’ gestation survive; neonatal survival of live births at 24–25 weeks’ gestation is 45%, 78% at 26–27 weeks’, 90% at 28–31 weeks’, and over 99% at 32 weeks’ and above (Victoria, Australia, 2006).

The morbidity of the surviving infants has decreased in recent years; the highest morbidity is among infants whose gestational age is less than 27 weeks and whose birthweight is 750 g or less. An Australian study of outcome at 2 years of age of 168 surviving infants (a survival rate of 73%) who were born with birthweights less than 1000 g showed that 51% had no disability, 23% a mild disability, 13% a moderate and 14% a severe disability, 11% had cerebral palsy, 2% were blind and 2% were deaf. For those born 20 years earlier the survival rate was 25%; disability rates were mild 33%, moderate 13% and severe 15%, cerebral palsy 14%, blindness 7% and deafness 5% (Table 27.2).