21 The lecture and teaching with large groups

The use of lectures

Brown and Manogue (2001) describe lectures as an economical and efficient method of conveying information to large groups of students. The lecture can provide an entrée into a difficult topic, it can offer different perspectives on a subject, it can communicate relevant personal, clinical or laboratory experience, and it can deliver a research-based view where teaching is immersed in a research-intensive university.

Problems with lectures

Problems attributed to the lecture may be the result of a ‘bad lecturer’ or the inappropriate use of the lecture. Common criticisms of lectures (Fig. 21.1) include:

• The lecture is a passive learning experience with a failure to engage the students in their own learning.

• Much of what is covered can be learned better from reading a book or engaging in an online programme.

• The delivery is difficult to follow with the visuals overloaded with information.

• The content of the lecture is inappropriate for the audience and is irrelevant, too advanced or too simple.

When to use lectures

Lectures, if used properly, offer a number of advantages:

• The lecturer can meet simultaneously with a large group of students and convey his or her passion and enthusiasm for a subject.

• The lecture can serve as an introduction to a difficult topic and provide the students with a framework for their further studies.

• Dealing with a controversial area, the lecture can provide different perspectives and at the same time relate the topic to the local context.

• In an advancing area of knowledge, the lecture can provide up-to-date information and highlight the contributions of research in an area.

• The lecture can be used to provoke thought and discussion and to encourage the student to reflect on the topic.

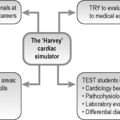

• The lecture can include a practical demonstration, for example with a cardiac simulator or a patient introduced to illustrate a point (with the agreement of the patient).

• The lecture can provide the students with guidelines about their further study of the topic and can introduce the resources available.

Delivering a good lecture

Get some facts in advance

Before concentrating on the content of the lecture, first do some fact finding:

• Refer to the statement of learning outcomes for the course. This should provide a clear idea of the purpose of the lecture and how it fits into the curriculum.

• Find out what the students already know about the subject of the lecture.

• Establish whether the lecture is one of a series of lectures on the subject and, if so, what the other lectures cover.

Think about the content and structure

Plan in advance the content and structure of the lecture:

• Plan the content for a lecture the students will wish to hear rather than the lecture you would like to give.

• Create a title for the lecture. It is sometimes easier to get started with the content if you first think of a title as it helps to structure your thoughts. It is more likely to interest students if the title is in the form of a question.

• Consider how you wish to structure the lecture. Two commonly used approaches are the classical method, where the lecture content is divided up into broad areas which are then subdivided, and the problem-centred approach where a problem or case study is presented and solutions are discussed. This chapter focuses on the classical approach although most of the tips given apply to both approaches.

• Lecturing styles vary considerably, so you must choose the style you feel most comfortable with and which suits your personality.

Visual aids

PowerPoint is an application designed to help the speaker or lecturer assemble professional looking slides and is widely used in oral presentations. The result sadly is often an unending stream of slides with bullet lists, animations that obscure rather than clarify the point and cartoons that distract from rather than convey the message. A host of sites are available on the web that provide practical advice on PowerPoint presentations and can help you to avoid ‘death by PowerPoint’ (Harden 2008).

Tips on lecturing

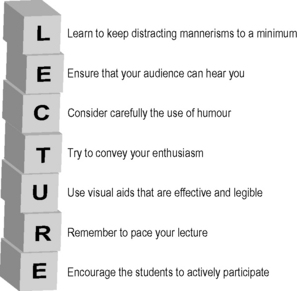

It is normal for a lecturer to feel just a little bit anxious before a lecture. Have a glass of water at the podium or nearby just in case you ‘dry up’. This will be less of a problem, however, if you have done the necessary preparation and have considered the following tips highlighted in the acronym ‘LECTURE’ (Fig. 21.2):

• Learn to keep distracting mannerisms to a minimum – taking spectacles off and putting them back on or jingling coins can be annoying.

• Ensure that your audience, especially those at the back of the theatre or classroom, can hear you.

• Consider carefully the use of humour. Does it add to your lecture and can you really deliver the joke or cartoon or will your attempts fall flat?

• Try to convey your enthusiasm and passion for the subject. This will be almost impossible if you read your notes. You need to vary the volume, pitch and speed of your delivery.

• Use visual aids that are effective and are legible and be sure to rehearse with the equipment and lighting before the start of the lecture.

• Remember to pace your lecture and allow time for note-taking. Speaking at the rate of an express train will not go down well with students who are struggling to keep up.

• Encourage the students to actively participate in the lecture without them feeling inhibited or threatened and leave time at the end for questions or discussion. Some strategies for engaging the audience are described below.

Engaging the audience

• Introduce at various stages during the lecture questions on the subject with a number of alternative answers presented. Students are asked to respond using an electronic response system, or coloured cards can be used with a different colour corresponding to each answer.

• Incorporate mini brainstorming sessions during the lecture where groups of three, four or five students next to each other are encouraged to discuss a topic. Some groups are asked to report back to the whole class. Alternatively the groups may answer and respond to a multiple choice question using cards or an audience response system. This is a key activity in team-based learning.

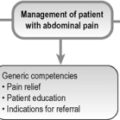

• Introduce or build your presentation around a case study or patient management problem, involving the class as the problem develops.

Reflect and react

1. How would you rate your ability as a lecturer? What might you do to improve your performance?

2. Have you evaluated your performance from the perspective of your students or your peers?

3. What do you see as the main purpose of your lecture – to inform the students, to encourage them to reflect and think or to influence their attitudes to the subject?

Brown G., Manogue M. Refreshing lecturing: a guide for lecturers. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 22. Med. Teach.. 2001;23:231-244.

Harden R.M. Death by PowerPoint – the need for a ‘fidget index’. Med. Teach.. 2008;30:833-835.

Some practical hints on the use of PowerPoint in presentations.

Newman L.R., Lown B.A., Jones R.N., et al. Developing a peer assessment of lecturing instrument: lessons learned. Acad. Med.. 2009;84:1104-1110.

O’Brien T.E., Wang W., Medvedev I., et al. Use of a computerized audience response system in medical student teaching: its effect on exam performance. Med. Teach.. 2006;28:736-738.

Robertson L.J. Twelve tips for using computerised interactive audience response system. Med. Teach.. 2000;22:237-239.