Chapter 1

The Interviewer’s Questions

What is spoken of as a “clinical picture” is not just a photograph of a man sick in bed; it is an impressionistic painting of the patient surrounded by his home, his work, his relations, his friends, his joys, sorrows, hopes and fears.

Francis Weld Peabody (1881–1927)

Basic Principles

Good communication skills are the foundation of excellent medical care. Even with the exciting new technology that has appeared since 2000, communicative behavior is still paramount in the care of patients. Studies have shown that good communication improves health outcomes by resolving symptoms and reducing patients’ psychological distress and anxiety. In the United States, 85% of all malpractice law suits are based on poor communication skills. It is not that the doctor didn’t know enough; the doctor did not communicate well enough with the patient!

Technologic medicine cannot substitute for words and behavior in serving the ill. The quality of patient care depends greatly on the skills of interviewing, because the relationship that a patient has with a physician is one of the most extraordinary relationships between two human beings. Within a matter of minutes, two strangers—the patient and the healer—begin to discuss intimate details about a person’s life. Once trust is established, the patient feels at ease discussing the most personal details of the illness. Clearly, a strong bond, a therapeutic alliance, has to have been established.

The main purpose of an interview is to gather all basic information pertinent to the patient’s illness and the patient’s adaptation to illness. An assessment of the patient’s condition can then be made. An experienced interviewer considers all the aspects of the patient’s presentation and then follows the leads that appear to merit the most attention. The interviewer should also be aware of the influence of social, economic, and cultural factors in shaping the nature of the patient’s problems. Other important aspects of the interview are educating the patient about the diagnosis, negotiating a management plan, and counseling about behavioral changes.

Any patient who seeks consultation from a clinician needs to be evaluated in the broadest sense. The clinician must be keenly aware of all clues, obvious or subtle. Although body language is important, the spoken word remains the central diagnostic tool in medicine. For this reason, the art of speaking and active listening continues to be central to the doctor-patient interaction. Active listening takes practice and involves awareness of what is being said in addition to body language and other nonverbal clues. For the novice interviewer, it is very easy to think only about your next question without observing the entire picture of the patient, as described masterfully in the quote by Peabody that introduced this chapter. Once all the clues from the history have been gathered, the assimilation of those clues into an ultimate diagnosis is relatively easy.

Communication is the key to a successful interview. The interviewer must be able to ask questions of the patient freely. These questions must always be understood easily and adjusted to the medical sophistication of the patient. If necessary, slang words describing certain conditions may be used to facilitate communication and avoid misunderstanding.

The success of any interview depends on its being patient-centered and not doctor-centered. Encourage the patient to tell his or her story and follow the patient’s leads to better comprehend the problems, concerns, and requests. Do not have your own list of “standard questions” as would occur in a symptom-focused, doctor-centered interview. Patients are not standard; don’t treat them as such. Allow the patient to tell his or her story in his or her own words. In the words of Sir William Osler (1893), “Listen to your patient. He is telling you the diagnosis. . . . The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.” No truer words have been spoken.

Once the patient has told his or her story of the history of the present illness, it is customary for you to move from open-ended questions to direct, more focused questions. Always start by casting a wide net and then gradually close the net to develop your differential diagnosis. Start general and then get more specific to clarify the patient’s story and symptoms.

Using an Interpreter

Health care providers are increasingly treating patients across language barriers. In 2006, nearly 49.6 million Americans had a “mother tongue” other than English; an additional 22.3 million (8.4%) had limited English proficiency. Lack of English proficiency can have deleterious effects. For any patient who speaks a language other than that of the health care provider, it is important to seek the help of a trained medical interpreter. Unless fluent in the patient’s language and culture, the health care provider should always use an interpreter. The interpreter can be thought of as a bridge, spanning the ideas, mores, biases, emotions, and problems of the clinician and patient. The communication is very much influenced by the extent to which the patient, the interpreter, and the provider share the same understanding and beliefs regarding the patient’s problem. The best interpreters are those who are familiar with the patient’s culture. The interpreter’s presence, however, adds another variable in the doctor-patient relationship; for example, a family member who translates for the patient may alter the meaning of what has been said. When a family member is the interpreter, the patient may be reluctant to provide information about sensitive issues, such as sexual history or substance abuse. It is therefore advantageous to have a disinterested observer act as interpreter. On occasion, the patient may request that a family member be the interpreter. In such a case, clinicians should respect the patient’s wishes. Friends of the patient, although helpful in times of emergency, should not be relied on as translators because their skills are unknown and confidentiality is a concern. The clinician should also master a number of key words and phrases in several common languages to gain the respect and confidence of patients. When using an interpreter, clinicians should remember the following guidelines:

1. Choose an individual trained in medical terminology.

2. Choose a person of the same sex as the patient and of comparable age.

3. Talk with the interpreter beforehand to establish an approach.

4. When speaking to the patient, watch the patient, not the interpreter.

5. Do not expect a word-for-word translation.

6. Ask the interpreter about the patient’s fears and expectations.

7. Use clear, short, and simple questions.

9. Keep your explanations brief.

10. Avoid questions using if, would, and could, because these require nuances of language.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has put together a useful mnemonic (INTERPRET) for working with interpreters in a cultural setting:

Even with a trained translator, health care workers are ultimately responsible for ensuring safe and effective communication with their patients. A recent article (Schenker et al., 2008) describes a conceptual framework of when to call for an interpreter and what to do when one is not available.

When speaking with the patient, the interviewer must determine not only the main medical problems but also the patient’s reaction to the illness. This is of great importance. How has the illness affected the patient? How has he or she reacted to it? What influence has it had on the family? On work? On social life?

The best interview is conducted by an interviewer who is cheerful, friendly, and genuinely concerned about the patient. This type of approach is clearly better than that of the interviewer who acts like an interrogator shooting questions from a standard list at the poor, defenseless patient. Bombarding patients with rapid-fire questions is a technique that should not be used.

Important Interviewing Concepts

In the beginning, the patient brings up the subjects that are easiest to discuss. More painful experiences can be elicited by tactful questioning. The novice interviewer needs to gain experience to feel comfortable asking questions about subjects that are more painful, delicate, or unpleasant. Timing of such questions is critical.

A cardinal principle of interviewing is to permit patients to express their stories in their own words. The manner in which patients tell their stories reveals much about the nature of their illnesses. Careful observation of a patient’s facial expressions, as well as body movements, may provide valuable nonverbal clues. The interviewer may also use body language such as a smile, nod, silence, hand gesture, or questioning look to encourage the patient to continue the story.

Listening without interruption is important and requires skill. If given the chance, patients often disclose their problems spontaneously. Interviewers need to hear what is being said. They must allow the patient to finish his or her answer even if there are pauses while the patient processes his or her feelings. All too often, an interview may fail to reveal all the clues because the interviewer did not listen adequately to the patient. Several studies have shown that clinicians commonly do not listen adequately to their patients. One study showed that clinicians interrupt the patient within the first 15 seconds of the interview. The interviewers are abrupt, appear uninterested in the patient’s distress, and are prone to control the interview.

As mentioned earlier, the best clinical interview focuses on the patient, not on the clinician’s agenda.

An important rule for improved interviewing is to listen more, talk less, and interrupt infrequently. Interrupting disrupts the patient’s train of thought. Allow the patient, at least in part, to control the interview.

Interviewers should be attentive to how patients use their words to conceal or reveal their thoughts and history. Interviewers should be wary of quick, very positive statements such as, “Everything’s fine,” “I’m very happy,” or “No problems.” If interviewers have reason to doubt these statements, they may respond by saying, “Is everything really as fine as it could be?”

If the history given is vague, the interviewer may use direct questioning. Asking “how,” “where,” or “when” is generally more effective than asking “why,” which tends to put patients on the defensive. Often replacing the word “Why . . .” with “What’s the reason . . .” will allow for better, less confrontational dialogue. The interviewer must be particularly careful not to disapprove of certain aspects of the patient’s story. Different cultures have different mores, and the interviewer must listen without any suggestion of prejudice.

Always treat the patient with respect. Do not contradict or impose your own moral standards on the patient. Knowledge of the patient’s social and economic background will make the interview progress more smoothly. Respect all patients regardless of their age, gender, beliefs, intelligence, educational background, legal status, practices, culture, illness, body habitus, emotional condition, or economic state.

Clinicians must be compassionate and interested in the patient’s story. They must create an atmosphere of openness in which the patient feels comfortable and is encouraged to describe the problem. These guidelines set the foundation for effective interviewing.

The interviewer’s appearance can influence the success of the interview. Patients have an image of clinicians. Neatness counts; a slovenly interviewer might be considered immature or careless, and his or her competence may be questioned from the start. Surveys of patients indicate that patients prefer medical personnel to dress in white coats and to wear shoes instead of sneakers.

As a rule, patients like to respond to questions in a way that satisfies the clinician to gain his or her approval. This may represent fear on the part of patients. The clinician should be aware of this phenomenon.

The interviewer must be able to question patients about subjects that may be distressing or embarrassing to the interviewer, the patient, or both. Answers to many routine questions may cause embarrassment to interviewers and leave them speechless. Therefore there is a tendency to avoid such questions. The interviewer’s ability to be open and frank about such topics promotes the likelihood of discussion in those areas.

Very often, patients feel comfortable discussing what an interviewer might consider antisocial behavior. This may include drug addiction, unlawful actions, or sexual behavior that does not conform to societal norms. Interviewers must be careful not to pass judgment on such behavior. Should an interviewer pass judgment, the patient may reject him or her as an unsuitable listener. Acceptance, however, indicates to the patient that the interviewer is sensitive. It is important not to imply approval of behavior; this may reinforce behavior that is actually destructive.

Follow the “rule of five vowels” when conducting an interview. According to this rule, a good interview contains the elements of audition, evaluation, inquiry, observation, and understanding. Audition reminds the interviewer to listen carefully to the patient’s story. Evaluation refers to sorting out relevant from irrelevant data and to the importance of the data. Inquiry leads the interviewer to probe into significant areas in which more clarification is required. Observation refers to the importance of nonverbal communication, regardless of what is said. Understanding the patient’s concerns and apprehensions enables the interviewer to play a more empathetic role.

Speech Patterns

Speech patterns, referred to as paralanguage components, are relevant to the interview. By manipulating the intonation, rate, emphasis, and volume of speech, both the interviewer and the patient can convey significant emotional meaning through their dialogue. By controlling intonation, the interviewer or patient can change the entire meaning of words. Because many of these features are not under conscious control, they may provide an important statement about the patient’s personal attributes. These audible parameters are useful in detecting a patient’s anxiety or depression, as well as other affective and emotional states. The interviewer’s use of a warm, soft tone is soothing to the patient and enhances the communication.

Body Language

A broad interest in body language has evolved. Body language, technically known as kinesics, is a significant aspect of modern communications and relationships. This type of nonverbal communication, in association with spoken language, can provide a more comprehensive picture of the patient’s behavior. Your own body language reveals your feelings and meanings to others. Your patient’s body language reveals his or her feelings and meanings to you. The sending and receiving of body language signals happens on conscious and unconscious levels.

It is well known that the interviewer may learn more about the patient from the way the patient tells the story than from the story itself. A patient who moves about in a chair and looks embarrassed is uncomfortable. A frown indicates annoyance or disapproval. Lack of comprehension is indicated by knitted brows. Body language experts generally agree that hands send more signals than any part of the body except for the face. A patient who strikes a fist on a table while talking is dramatically emphasizing what he or she is saying. A patient who slips a wedding band on and off may be ambivalent about his or her marriage. A palm placed over the heart asserts sincerity or credibility. Many people rub or cover their eyes when they refuse to accept something that is pointed out. When patients disapprove of a statement made by the interviewer but restrain themselves from speaking, they may start to remove dust or lint from their clothing.

Six universal emotional facial expressions are recognized around the world. The use and recognition of these expressions is genetically inherited rather than socially conditioned or learned. Although minor variations and differences are found among isolated people, the following basic human emotions are generally used, recognized, and part of humankind’s genetic character:

Of interest, Charles Darwin was first to make these claims in his book The Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals, published in 1872.

Smiling is an important part of body language. As a general rule, a genuine smile is symmetrical and produces creases around the eyes and mouth, whereas a fake smile tends to be a mouth-only gesture.

Arms act as defensive barriers when across the body, and conversely indicate feelings of openness and security when in open positions, especially combined with open palms. Arms are quite reliable indicators of mood and feeling, especially when interpreted with other body language. For example:

• Crossed arms may indicate defensiveness.

• Crossed arms and crossed legs probably indicate defensiveness.

Full interpretation of body language can be made only in the context of the patient’s cultural and ethnic background because different cultures have different standards for nonverbal behavior. Middle Eastern and Asian patients often speak with dropped eyelids. This type of body language indicates depression or lack of attentiveness in a patient from the United States. The interviewer may use facial expressions to facilitate the interview. An appearance of attention demonstrates an interest in what the patient is describing. Attentiveness on the part of the interviewer is also indicated by leaning slightly forward toward the patient.

Body language in a certain situation might not mean the same in another. Occasionally, body language isn’t what it seems. For example:

• Someone rubbing his or her eye might have an irritation, rather than being disbelieving or upset.

• Someone with crossed arms might be keeping warm, rather than being defensive.

• Someone scratching his or her nose might actually have an itch, rather than concealing a lie.

A single body language signal isn’t as reliable as several signals. As with any system of evidence, groups of body language signals provide much more reliable indication of meaning than one or two signals in isolation. Avoid interpreting only single signals. Look for combinations of signals that support an overall conclusion, especially for signals that can mean two or more quite different things. It is important to recognize that body language is not an exact science.

Touch

Touching the patient can also be very useful. Touch can communicate warmth, affection, caring, and understanding. Many factors, including gender and cultural background, as well as the location of the touch, influence the response to the touch. Although there are wide variations within each cultural group, Latinos and people of Mediterranean descent tend to use a great deal of contact, whereas British and Asians tend not to use contact. Scandinavians and Anglo-Saxon Americans are in the middle of this range. Be aware, however, that certain religious groups prohibit touching a person of the opposite sex. In general, the older the patient, the more important touch is. Appropriate placement of a hand on a patient’s shoulder suggests support. Never place a hand on a patient’s leg or thigh, because this is a threatening touch. An interviewer who walks with good posture to a patient’s bedside can hope to gain the patient’s respect and confidence. An interviewer who maintains eye contact with the patient conveys interest in the patient.

Depersonalization of the Doctor-Patient Relationship

In this age of biomedical advancements, a new problem has arisen: a depersonalization of the doctor-patient relationship. Clinicians may order computed tomography scans or sonograms without taking the appropriate time to speak with the patient about the tests. Both doctor and patient may feel increasingly neglected, rejected, or abused. Patients may feel dehumanized on admission to the hospital. Many find themselves in a strange environment, lying naked while clothed people march in and out of the room and touch them, tell them what to do, and so forth. They may be apprehensive because they have a problem that their health care provider considers too serious to be treated on an outpatient basis. Their future is filled with uncertainty. A patient admitted to the hospital is stripped of clothing and often of dentures, glasses, hearing aids, and other personal belongings. A name tag is placed on the patient’s wrist, and he or she becomes “the patient in 9W-310.” This lowers the morale of the patient even more. At the same time, clinicians may be pressed for time, overworked, and sometimes unable to cope with everyday pressures. They may be irritable and pay inadequate attention to the patient’s story. They may eventually come to rely on the technical results and reports. This failure to communicate weakens the doctor-patient relationship.

Inexperienced interviewers not only must learn about the patient’s problems but also must gain insight into their own feelings, attitudes, and vulnerabilities. Such introspection enhances the self-image of the interviewer and results in the interviewer’s being perceived by the patient as a more careful and compassionate human being to whom the patient can turn in a time of crisis.

A good interviewing session determines what the patients comprehend about their own health problems. What do the patients think is wrong with them? Do not accept merely the diagnosis. Inquire specifically as to what the patient thinks is happening. What kind of effect does the illness have on the patient’s work, family, or financial situation? Is there a feeling of loss of control? Does the patient feel guilt about the illness? Does the patient think that he or she will die? By pondering these questions, you can learn much about patients, and patients will realize that you are interested in them as whole persons, not merely as statistics among the hospital admissions.

Medical Malpractice and Communication Skills

The literature indicates that malpractice suits have increased at an alarming rate. A good doctor-patient relationship is probably the most important factor in avoiding malpractice claims. As mentioned previously, most malpractice litigation is the result of a deterioration in communication and of patient dissatisfaction rather than of true medical negligence. The patient who is likely to sue has become dissatisfied with the clinician and may have lost respect for him or her. From the patient’s point of view, the most serious barriers to a good relationship are the clinician’s lack of time; seeming lack of concern for the patient’s problem; inability to be reached; attitude of superiority, arrogance, or indifference; and failure to inform the patient adequately about his or her illness. Failure to discuss the patient’s illness and treatment in understandable terms is viewed as a rejection by the patient. In addition, the congeniality and competence of a physician’s office staff can go a long way toward avoiding malpractice suits. Physicians who have never been sued orient their patients to the process of the visit, use facilitative comments, ask the patient for opinions, use active learning, use humor and laughter, and have longer visits. A doctor-patient relationship based on honesty and understanding is thus recognized as essential for good medical practice and the well-being of the patient.

It is sometimes difficult for a novice interviewer to remember that there is no need to try to make a diagnosis out of every bit of information obtained from the interview. Accept all the clues and then work with them later when trying to establish a diagnosis.

If during the interview you cannot answer a question, do not. You can always act as the patient’s advocate; listen to the question and then find someone who can provide an appropriate answer.

Doctor-Patient Engagement

A very important task of communication is to engage the patient. A helpful way of building rapport with a patient is to be curious about the person as a whole. Ask, “Before we begin, tell me something about yourself.” When the patient returns, mention something personal that you learned from a previous visit, for instance, “How was your trip to Seattle to see your son?” Another part of engagement is to determine the patient’s expectations from the visit; for instance, ask, “What are you hoping to accomplish today?” At the conclusion of the visit, ask, “Is there anything else you are concerned about?” If the patient has several problems, it is acceptable to say, “We might need to discuss that problem at another visit. I want to be certain that we completely evaluate your main concern today.”

Privacy Standards

On April 14, 2003, the first federal privacy standards were put in place to protect the medical records and other health information of patients. The U.S. Congress asked the Department of Health and Human Services to issue privacy protection as part of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. HIPAA regulations include provisions designed to encourage electronic transactions and to safeguard the security and confidentiality of health information. The final regulations cover health plans, health care clearinghouses, and health care providers who conduct financial and administrative transactions electronically. In short, these regulations regarding patient confidentiality limit the ways in which health care providers, health plans, pharmacies, hospitals, clinics, and other entities can use patients’ personal medical information. These regulations ensure that medical records and other identifiable health information, whether on paper, in computers, or orally communicated, are protected.

In summary, the medical interview is a blend of the cognitive and technical skills of the interviewer and the feelings and personalities of both the patient and the interviewer. The interview should be flexible and spontaneous and not interrogative. When used correctly, it is a powerful diagnostic tool.

Symptoms and Signs

The clinician must be able to elicit descriptions of, and recognize, a wide variety of symptoms and signs. Symptom refers to what the patient feels. Symptoms are described by the patient to clarify the nature of the illness. Shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, diarrhea, and double vision are all symptoms. These labels help the patient describe the discomfort or distress that he or she is experiencing. Symptoms are not absolute; they are influenced by culture, intelligence, and socioeconomic background. As an example, consider the symptom of pain. Patients have different thresholds of pain. This is discussed further in Chapter 27, Caring for Patients in a Culturally Diverse Society, which can be accessed on the internet version of this textbook.

Constitutional symptoms are symptoms that commonly occur with problems in any of the body systems, such as fever, chills, weight loss, or excessive sweating.

A sign is what the examiner finds. Signs can be observed and quantified. Certain signs are also symptoms. For example, a patient may describe episodes of wheezing; this is a symptom. In addition, an examiner may hear wheezing during a patient’s physical examination; this is a sign.

The major task of the interviewer is to sort out the symptoms and signs associated with a specific illness. A major advantage that the seasoned interviewer has over the novice is a better understanding of the pathophysiologic processes of disease states. The novice operates under the limitation of not knowing all the signs and symptoms of the associated diseases. With experience and education, the novice will recognize the combination of symptoms and signs as they relate to the underlying illness. For any given disease, certain symptoms and signs tend to occur together. When there is only an isolated symptom, the interviewer must be careful in making a definitive assessment.

Conducting an Interview

Getting Started and Introduction

The diagnostic process begins at the first moment of meeting. You should be dressed appropriately, wearing a white coat with your name badge identifying you as a member of the health care team. Patients expect this standard of professional attire. Casual attire may signify condescension.

Introduce yourself, greet the patient by last name, make eye contact, shake hands firmly, and smile. You may wish to say something like

Alternatively, you may say,

or

The term student doctor should generally be avoided because patients may not actually understand this term; they may hear only the word doctor. The introduction also includes a statement of the purpose of the visit. The welcoming handshake can serve to relax the patient.

It is appropriate to address patients by their correct titles—“Mr.,” “Mrs.,” “Miss,” “Dr.,” “Ms.”—unless they are adolescents or younger. A formal address clarifies the professional nature of the interview. For a woman, the default always is “Ms.” unless you know positively that a woman wishes to be addressed as “Miss” or “Mrs.” Name substitutes such as “dear,” “honey,” or “grandpa” are not to be used. Also, avoid using “Sir” or “Ma’am.” “Ma’am” is mostly obsolete, with a few exceptions. It is commonly used to address any woman in the southern or southwestern areas of the United States. Use the patient’s name. If you are not sure about the pronunciation, ask the patient how to say his or her name correctly.

The patient may address an interviewer as Ms. Jones, for example, or might elect to use the interviewer’s first name. It is not correct for an interviewer to address the patient by his or her first name, because this changes the professional nature of this first meeting.

If the patient is having a meal, ask whether you can return when he or she has finished eating. If the patient is using a urinal or bedpan, allow privacy. Do not begin an interview in this setting. If the patient has a visitor, you may inquire whether the patient wishes the visitor to stay. Do not assume that the visitor is a family member. Allow the patient to introduce the person to you.

The interview can be helped or hindered by the physical setting in which the interview is conducted. If possible, the interview should take place in a quiet, well-lit room. Unfortunately, most hospital rooms do not afford such luxury. The teaching hospital with four patients in a room is rarely conducive to good human interactions. Therefore make the best of the existing environment. The curtains should be drawn around the patient’s bed to create privacy and minimize distractions. You may request that the volume of neighboring patients’ radios or televisions be turned down. Lights and window shades can be adjusted to eliminate excessive glare or shade. Arrange the patient’s bed light so that the patient does not feel as if he or she is under interrogation.

You should make the patient as comfortable as possible. If the patient’s eyeglasses, hearing aids, or dentures were removed, ask whether the patient would like to use them. It may be useful to use your stethoscope as a hearing aid for hearing-impaired patients. The ear tips are placed in the ears of the patient, and the diaphragm serves as a microphone. The patient may be in a chair or lying in bed. Allow the patient the choice of position. This makes the patient feel that you are interested and concerned, and it allows the patient some control over the interview. If the patient is in bed, it is a nice gesture to ask whether the pillows should be arranged to make him or her more comfortable before the interview begins.

To Stand or to Sit?

Normally, the interviewer and patient should be seated comfortably at the same level. Sometimes it is useful to have the patient sitting even higher than the interviewer to give the patient the visual advantage. In this position, the patient may find it easier to open up to questions. The interviewer should sit in a chair directly facing the patient to make good eye contact. Sitting on the bed is too familiar and not appropriate. It is generally preferred that the interviewer sit at a distance of about 3 to 4 feet from the patient. Distances greater than 5 feet are impersonal, and distances closer than 3 feet interfere with the patient’s “private space.” The interviewer should sit in a relaxed position without crossing arms across the chest. The crossed-arms position is not appropriate because this body language projects an attitude of superiority and may interfere with the progress of the interview.

If the patient is bedridden, raise the head of the bed, or ask the patient to sit so that your eyes and the patient’s eyes are at the same level. Avoid standing over the patient. Try to lower the bed rail so that it does not act as a barrier to communication, and remember to put it back up at the conclusion of the session.

Regardless of whether the patient is sitting in a chair or lying in bed, make sure that he or she is appropriately draped with a sheet or robe.

The Opening Statement

Once the introduction has been made, the interview may begin with a general, open-ended question, such as “What medical problem has brought you to the hospital?” or “I understand you are having. . . . Tell me more about the problem.” This type of opening remark allows the patient to speak first. The interviewer can then determine the patient’s chief complaint: the problem that is regarded as paramount. If the patient says, “Haven’t you read my records?” it is correct to say, “No, I’ve been asked to interview you without any prior information.” Alternatively, the interviewer could say, “I would like to hear your story in your own words.”

Patients can determine very quickly if you are friendly and personally interested in them. You may want to establish rapport by asking them something about themselves before you begin diagnostic questioning. Take a few minutes to get to know the patient. If the patient is not acutely ill, you may want to say, “Before I find out about your headache, tell me a little about yourself.” This technique puts the patient at ease and encourages him or her to start talking. The patient usually talks about happy things in his or her life rather than the medical problems. It also conveys your interest in the patient as a person, not just as a vehicle of disease.

The Narrative

Novice interviewers are often worried about remembering the patient’s history. However, it is poor form to write extensive notes during the interview. Attention should be focused more on what the person is saying and less on the written word. In addition, by taking notes, the interviewer cannot observe the facial expressions and body language that are so important to the patient’s story. A pad of paper may be used to jot down important dates or names during the session.

After the introductory question, the interviewer should proceed to questions related to the chief complaint. These should naturally evolve into questions related to the other formal parts of the medical history, such as the present illness, past illnesses, social and family history, and review of body systems. Patients should largely be allowed to conduct the narrative in their own way. The interviewer must select certain aspects that require further details and guide the patient toward them. Overdirection is to be avoided because this stifles the interview and prevents important points from being clarified.

Small talk is a useful method of enhancing the narrative. Small talk, also known as “chit-chat,” is neither random nor pointless, and studies in conversation analysis indicate that it is actually useful in communication. It has been shown that during conversations, the individual who tells a humorous anecdote is the one who is in control. For example, if an interviewer interjects a humorous remark during an interview and the patient laughs, the interviewer is in control of the conversation. If the patient does not laugh, the patient may take control.

Be alert when a patient says, “Let me ask you a hypothetical question” or “I have a friend with . . . ; what do you think about . . . ?” In each case, the question is probably related to the patient’s own concerns.

A patient often uses utterances such as “uh,” “ah,” and “well” to avoid unpleasant topics. It is natural for a patient to delay talking about an unpleasant situation or condition. Pauses between words, as well as the use of these words, provide a means for the patient to put off discussing a painful subject.

When patients use vague terms such as “often,” “somewhat,” “a little,” “fair,” “reasonably well,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “average,” the interviewer must always ask for clarification: “What does sometimes mean?” “How often is often?” Even terms such as “dizzy,” “weak,” “diarrhea,” and “tired” necessitate explanation. Precise communication is always desirable, and these terms, among others, have significant variations in meaning.

The interviewer should be alert for subtle clues from the patient to guide the interview further. There are a variety of techniques to encourage and sustain the narrative. These guidelines consist of verbal and nonverbal facilitation, reflection, confrontation, interpretation, and directed questioning. These techniques are discussed later in this chapter.

The Closing

It is important that the interviewer pace the interview so that adequate time is left for the patient to ask questions and for the physical examination. About 5 minutes before the end of the interview, the interviewer should begin to summarize the important issues that were discussed.

If the patient asks for an opinion, it is prudent for the novice interviewer to answer, “I am a medical student. I think it would be best to ask your doctor that question.” You have not provided the patient with the answer that he or she was seeking; however, you have not jeopardized the existing doctor-patient relationship by possibly giving the wrong information or a different opinion.

At the conclusion, it is polite to encourage the patient to discuss any additional problems or to ask any questions: “Is there anything else you would like to tell me that I have not already asked?” “Are there any questions you might like to ask?” Usually, all possible avenues of discussion have been exhausted, but these remarks allow the patient the “final say.”

Thus a good closure should consist of the following four parts:

Basic Interviewing Techniques

The successful interview is smooth and spontaneous. The interviewer must be aware of subtleties and be able to pick up on these clues. The successful interviewer sustains the interview. Several techniques can be used to encourage someone to continue speaking, and this section discusses those interviewing techniques. Each technique has its limitations, and not all of them are used in every interview.

Questioning

The secret of effective interviewing lies in the art of questioning. The wording of the question is often less important than the tone of voice used to ask it. In general, questions that stimulate the patient to talk freely are preferred.

Open-Ended Questions

Open-ended questions are used to ask the patient for general information. This type of question is most useful in beginning the interview or for changing the topic to be discussed. An open-ended question allows the patient to tell his or her story spontaneously and does not presuppose a specific answer. It can be useful to allow the patient to “ramble on.” An open-ended question is a question that cannot be answered by saying “Yes” or “No.” Examples of open-ended questions are the following:

“What kind of medical problem are you having?”

“Are you having stomach pain? Tell me about it.”

“Tell me about your headache.”

“How was your health before your heart attack?”

Too much rambling, however, must be controlled by the interviewer in a sensitive but firm manner. This freedom of speech should obviously be avoided with overtalkative patients, whereas it should be used often with silent patients.

Direct Questions

After a period of open-ended questioning, the interviewer should direct the attention to specific facts learned during the open-ended questioning period. These direct questions serve to clarify and add detail to the story. This type of question gives the patient little room for explanation or qualification. A direct question can usually be answered in one word or a brief sentence; for example:

Care must be taken to avoid asking direct questions in a manner that might bias the response.

Symptoms are classically characterized according to several dimensions or elements, including bodily location, onset (and chronology), precipitating (and palliating) factors, quality, radiation, severity, temporal, and associated manifestations. These elements may be used as a framework to clarify the illness. Examples of appropriate questions follow.

Onset (and Chronology)

Precipitating Factors

Palliating Factors

Radiation

Severity (or Quantity)

“On a scale from 1 to 10, with 10 the worst pain you can imagine, how would you rate this pain?”

“How has the pain affected your lifestyle?”1

“What do you mean by ‘a lot’?”

“How many sanitary napkins do you use?”

“How many times did you vomit?”

“What kind of effect does the pain have on your work?”

“How does the pain compare with the time you broke your leg?”

Temporal

Associated Manifestations

“Do you have any other symptoms?”

“Do you ever have nausea with the pain?”

“Have you noticed other changes that happen when you start to sweat?”

“Before you get the headache, do you ever experience a strange taste or smell?”

The mnemonic O-P-Q-R-S-T, which stands for onset (chronology), precipitating (or palliative), quality, radiation, severity, and temporal, is useful in helping the interviewer remember these important dimensions of a symptom. The setting is also important to determine. Did the symptom occur when exposed to certain environmental conditions, during specific activities, during emotional periods, or under other circumstances?

Question Types to Avoid

There are several types of questions that should be avoided. One is the suggestive question, which provides the answer to the question. For example:

A better way to ask the same question would be as follows:

The why question carries tones of accusation. This type of question almost always asks a patient to account for his or her behavior and tends to put the patient on the defensive; for example:

The answers to such questions, however, are important. As mentioned previously, try rephrasing as “What is the reason . . . ?” The “why” question is useful in daily life with friends and family, with whom you have a relationship different from that with your patients; do not use it with patients.

The multiple or rapid-fire question should also be avoided. In this type of question, there is more than one point of inquiry. Don’t barrage the patient with a list of questions. The patient can easily get confused and respond incorrectly, answering no part of the question adequately. The patient may answer only the last inquiry heard; for example:

The other problem with multiple questions is that you may think you have asked the question, but the patient has answered only part of it. For example, in the first inquiry just mentioned, the patient may answer “No” to indicate “no chills,” but if you ask about the symptoms separately, you might find out that the patient does have a history of night sweats.

Questions should be concise and easily understandable. The context should be free of medical jargon. Frequently, novice interviewers try to use their new medical vocabularies to impress their patients. They may sometimes respond to the patient with technical terms, leaving the patient feeling confused or put down. By using medical jargon, the interviewer distances himself or herself from the patient. This use of technical medical terms is sometimes called doctorese or medicalese. For example:

“You seem to have a homonymous hemianopsia.”

“Have you ever had a myocardial infarction?”

“We perform Papanicolaou smears to check for cervical carcinoma in situ.”

“I am going to order a CBC with differential.”

“The MUGA scan shows that you have congestive heart failure.”

Medical terminology, as a rule, should not be used in conversations with patients. Technical terms scare patients who are unfamiliar with them. Every medical and nursing student understands the term heart failure, but a patient might interpret it as failure of the heart to pump—that is, cardiac standstill, or death. Although patients should be given only as much information as they can handle, adequate explanations must always be provided. A partial explanation can leave the patient confused and fearful. Conversely, patients may try to use medical terms themselves. Do not take these terms at face value; ask patients to describe what they mean. For example, some patients may use “heart attack” to describe angina, “stroke” to describe a transient ischemic attack, “spells” to describe dizziness, or “water pills” or “heart pills” when referring to their medication.

A leading or biased question carries a suggestion of the kind of response for which the interviewer is looking. For example, “You haven’t used any recreational drugs, have you?” suggests that the interviewer disapproves of the patient’s use of drugs. If the patient has used recreational drugs, he or she may not admit it under this line of questioning. Instead, ask, “Do you use recreational drugs?” Questions should be asked in the positive or affirmative mode, not the negative. Questions asked in the affirmative or positive mode convey a nonjudgmental approach and encourage the patient to answer more candidly without the fear of being blamed for an action.

It is also incorrect to ask, “You don’t have diabetes, do you?” or “You haven’t been wheezing, have you?” Instead, the interviewer should ask in the positive affirmative mode, “Do you have diabetes?” or “Have you been wheezing?” A leading question may also invite a particular answer. For example, “Did you notice that the pain came on after you vomited?”

In addition to avoiding certain types of questions, the interviewer should avoid certain situations. For example, patients may respond to a question in an unexpected manner, resulting in a period of unexpected silence on the part of the interviewer. This “stumped silence” can be interpreted by the patient in a variety of ways. The interviewer must be able to respond quickly in such instances, even if it means broaching another topic.

If a patient suggests that a test not be performed, perhaps because of an underlying fear of the test, the interviewer should never respond by stating, “I’m the doctor. I’ll make the decisions.” The interviewer should recognize the anxiety and handle the response from that point of view. He or she should ask the patient, “What are your concerns about taking the test?”

If a patient appears overweight, ask first whether there has been any change in the patient’s weight before asking whether he or she has tried to lose weight. The patient may have lost 30 pounds already but is still overweight. Never refer to an overweight person as obese.

Finally, assume nothing about patients’ knowledge of their disease, their sexual orientation or experiences, their education, their family, or their knowledge of illness in general. People come from different backgrounds and have different beliefs based on culture, religion, and experience. It is incorrect to assume that if a medicine has been prescribed for an illness, the patient is taking it correctly or actually taking it at all. Do not even presume that a patient is happy or sad about an event in his or her life or in the lives of friends and family. It is much safer to ask questions in the following manner:

Silence

Silence is most useful with silent patients. Silence should never be used with overtalkative patients, because letting them talk continuously would not allow the interviewer to control the interview. This difficult type of communication, when used correctly, can indicate interest and support. Silence on the part of the patient can be related to hostility, shyness, or embarrassment. The interviewer should remain silent, maintaining direct eye contact and attentiveness. The interviewer may lean forward and even nod. After no more than 2 minutes of silence, the interviewer may say,

If the patient remains silent, another method of sustaining the interview must be chosen.

The interviewer must use silence when the patient becomes overwhelmed by emotion. This act allows the patient to release some of the tension evoked by the history and indicates to the patient that it is acceptable to cry. Handing the patient a box of tissues is a supportive gesture. It is inappropriate for the interviewer to say, “Don’t cry” or “Pull yourself together” because these statements imply that the patient is wasting the interviewer’s time or that it is shameful to show emotions.

It is important to use silence correctly. An interviewer who remains silent, becomes fidgety, reviews notes, or makes a facial expression of evaluation will inhibit the patient. The patient may perceive the frequent use of silence by the interviewer as aloofness or a lack of knowledge.

Facilitation

Facilitation is a technique of verbal or nonverbal communication that encourages a patient to continue speaking but does not direct him or her to a topic. A common verbal facilitation is “Uh huh.” Other examples of verbal facilitations include “Go on,” “Tell me more about that,” “And then?” and “Hmm.”

An important nonverbal facilitation is nodding the head or making a hand gesture to continue. Moving toward the patient connotes interest. Be careful not to nod too much, as this may convey approval in situations in which approval may not be intended.

Often, a puzzled expression can be used as a nonverbal facilitation to indicate, “I don’t understand.”

Confrontation

Confrontation is a response based on an observation by the interviewer that points out something striking about the patient’s behavior or previous statement. This interviewing technique directs the patient’s attention to something of which he or she may or may not be aware. The confrontation may be either a statement or a question; for example:

“Is there any reason why you always look away when you talk to me?”

“You sound uncomfortable about it.”

Confrontation is particularly useful in encouraging the patient to continue the narrative when there are subtle clues given. By confronting the patient, the interviewer may enable the patient to explain the problem further. Confrontation is also useful to clarify discrepancies in the history.

Confrontation must be used with care; excessive use is considered impolite and overbearing. If correctly used, however, confrontation can be a powerful technique. Suppose a patient is describing a symptom of chest pain. By observing the patient, you notice that there are now tears in the patient’s eyes. By saying sympathetically, “You look very upset,” you are encouraging the patient to express emotions.

Interpretation

Interpretation is a type of confrontation that is based on inference rather than on observation. The interviewer interprets the patient’s behavior, encouraging the patient to observe his or her own role in the problem. The interviewer must fully understand the clues the patient has given before he or she can offer an interpretation. The interviewer must look for signs of underlying fear or anxiety that may be indicated by other symptoms, such as recurrent pain, dizziness, headaches, or weakness. Once these underlying fears have been discovered, the patient may be led to recognize the inciting event during future interviews. Interpretation frequently opens previously unrecognized lines of communication. Examples are the following:

“You seem to be quite happy about that.”

“Are you afraid you’ve done something wrong?”

“I wonder whether there’s a relation between your dizziness and arguments with your wife.”

Interpretation can demonstrate support and understanding if used correctly.

Reflection

Reflection is a response that mirrors or echoes that which has just been expressed by the patient. It encourages the patient to expound further on details of the statement. The tone of voice is important in reflection. The intonation of the words may indicate entirely different meanings. For example:

In this example, the emphasis should be on “2012.” This asks the patient to describe the conditions that did not allow him or her to work. If the emphasis is incorrectly placed on “worked,” the interviewer immediately puts the patient on the defensive, implying, “What did you do with your time?” Although often very useful, reflection can hamper the progress of an interview if used improperly.

Support

Support is a response that indicates an interest in or an understanding of the patient. Supportive remarks promote a feeling of security in the doctor-patient relationship. A supportive response might be “I understand.” An important time to use support is immediately after a patient has expressed strong feelings. The use of support when a patient suddenly begins to cry strengthens the doctor-patient relationship. Two important subgroups of support are reassurance and empathy.

Reassurance

Reassurance is a response that conveys to the patient that the interviewer understands what has been expressed. It may also indicate that the interviewer approves of something the patient has done or thought. It can be a powerful tool, but false reassurance can be devastating. Good examples of reassurance are the following:

“That’s wonderful! I’m delighted that you started in the rehabilitation program at the hospital.”

“That’s great that you were able to stop smoking.”

“It’s understandable why you are so upset after your accident.”

“It’s good you came in today. We will do everything to help you.”

The use of reassurance is particularly helpful when the patient seems upset or frightened. Reassurance must always be based on fact. Reassurance is very important because it tells the patient that his or her fears are understandable and real.

False reassurances restore a patient’s confidence but ignore the reality of the situation. Telling a patient that his or her “surgery will be successful” clearly discounts the known morbidity and mortality rates associated with it. The patient wants to hear such reassurance, but it may be false.

Never tell a patient to relax. Patients are often nervous and are entitled to be upset or worried. Try to instill confidence in your patient instead of trying to talk the patient out of being nervous. These comments may be counterintuitive. Telling a patient to be calm may send the message that you are uncomfortable with their problem or that you do not really understand the problem’s severity.

Empathy

Empathy is a response that recognizes the patient’s feeling and does not criticize it. It is understanding, not an emotional state of sympathy. You try to put yourself in the shoes of the patient. The empathic response is saying, “I hear what you’re saying.” The use of empathy can strengthen the doctor-patient relationship and allow the interview to flow smoothly. Examples of empathy are the following:

“I’m sure your daughter’s problem has given you much anxiety.”

“The death of someone so close to you is hard to take.”

“I guess this has been kind of a silent fear all your life.”

The last two examples illustrate an important point: it is critical to give credit to patients to encourage their role in their own improvement.

It is really impossible, however, to put yourself in the shoes of the patient because of a difference in age, gender, life experiences, education, culture, religion, and other factors. An extremely empathic statement, which sounds counterintuitive, is “It’s impossible for me to fully understand how you are feeling, but how can I help you? How can we work together to get past this problem?”

Empathetic responses can also be nonverbal. An understanding nod is an empathetic response. In certain circumstances, placing a hand on the shoulder of an upset patient communicates support. The interviewer conveys that he or she understands and appreciates how the patient feels without actually showing any emotion.

Transitions

Transitional statements are used as guides to allow the patient to understand better the logic of the interviewer’s questioning and for the interview to flow more smoothly from one topic to another. An example of a transitional statement might be, after learning about the current medical problem, the interviewer’s statement, “Now I am going to ask you some questions about your health history.” Other examples while the history is documented might be, “I am now going to ask you some questions about your family,” and “Let’s talk about your lifestyle and your activities in a typical day.”

Usually, the line of questioning being pursued is obvious to the patient, so transitions are not always needed. Transitioning to the sexual history, however, often requires a transitional statement. As an example, a transitional statement such as “I am now going to ask you some routine questions about your sexual history” may bridge to this area comfortably for both the patient and interviewer. An alternative transitional statement might be, “To determine your risk for several diseases, I am now going to ask you some questions about your sexual health [or sexual activity, or sexual habits].” Avoid phrases such as “personal habits” or “personal history,” because these expressions send the message of what the interviewer considers these habits to be; the patient may be more open to discuss this area and may not consider it “personal.” It is better to ask about “sexual habits,” “sexual activity,” or “sexual health,” rather than “sexual life.” Other words to be avoided include “like to,” “want to,” “need to,” or “have to” (e.g., “I would now like to ask you some questions about your sexual habits” or “I now have to ask you some questions about your sexual habits”). As will be discussed in subsequent chapters, always use specific language. Refer to the genitalia with explicit terms such as vagina, penis, uterus, and so on; do not use the term “private parts.”

Format of the History

The information obtained by the interviewer is organized into a comprehensive statement about the patient’s health. Traditionally, the history has been obtained by using a disease-oriented approach emphasizing the disease process that prompted the patient to seek medical advice. For example, a patient may present with shortness of breath; the interview would be conducted to ascertain the pathologic causes of the shortness of breath.

An alternative approach to obtaining the history is a patient-oriented one. This entails evaluating the patient and his or her problems more holistically. By using this approach, the health care provider can elicit a more complete history, keeping in mind that other symptoms (e.g., pain from arthritis, weakness, depression, anxiety) may have an effect on the patient’s shortness of breath. For example, if a patient has arthritis and cannot walk, shortness of breath may manifest as less severe than if the patient were able to walk and experienced shortness of breath with minimal activity. In this way, the entire patient is taken into account.

The major traditional sections of the history, with some patient-oriented changes, are as follows:

• History of the present illness and debilitating symptoms

• Occupational and environmental history

• Psychosocial and spiritual history

Source and Reliability

The source and reliability contains identifying data; source of the history; and, if appropriate, the source of the referral. The identifying data consist of the age and gender of the patient. The source of information is usually the patient. If the patient requires a translator, the source is the patient and the translator. If family members help in the interview, their names should be included in a single-sentence statement. The source could also be a medical record.

The reliability of the interview should be assessed. Is the patient competent to provide a history? Often determination of orientation to person, time, and place (discussed in Chapter 18, The Nervous System) is done early in the interview to assess the cognitive function of the person. If the patient is not oriented to person, time, and place, a statement such as, “The patient is a 76-year-old white man with a moderate cognitive impairment as manifested by a lack of orientation to person, time, and place who presents with. . . .” This indicates that the rest of the history needs to be taken with “a grain of salt” or that some or all of the history that follows may be inaccurate. The date and time of the interaction is also vital for the record.

Chief Complaint

The chief complaint is the patient’s brief statement explaining why he or she sought medical attention. Try to actually quote the patient’s own words. It is the answer to the question, “What is the medical problem that brought you to the hospital?” or “How can I help you today?” The chief complaint might then be:

“I’ve been having chest pain for the past 5 hours.”

“I have had terrible nausea and vomiting for 2 days.”

“I’ve got a splitting headache for the last few days.”

Patients sometimes use medical terms. The interviewer must ask the patient to define such terms to ascertain what the patient means by them.

History of Present Illness and Debilitating Symptoms

The history of the present illness refers to the recent changes in health that led the patient to seek medical attention at this time. It describes the information relevant to the chief complaint. It should answer the questions of what, when, how, where, which, who, and why. It provides a clear, chronologic explanation of the patient’s symptoms accounting for the reason the patient has sought medical attention.

Chronology is the most practical framework for organizing the history. It enables the interviewer to comprehend the sequential development of the underlying pathologic process. In this section, the interviewer gathers all the necessary information, starting with the first symptoms of the present illness and following its progression to the present day. To establish the beginning of the present illness, it is important to verify that the patient was entirely well before the earliest symptom. Patients often do not remember when a symptom developed. If the patient is uncertain about the presence of a symptom at a certain time, the interviewer may be able to relate it to an important or memorable event, for example, “Did you have the pain during your summer vacation?” In this part of the interview, mainly open-ended questions are asked because these afford the patient the greatest opportunity to describe the history.

In the patient-centered evaluation, the interviewer must determine whether any debilitating symptoms are also present and what effect they have on the patient. These symptoms include pain, constipation, weakness, nausea, shortness of breath, depression, and anxiety.

For each symptom, seven attributes are important to ascertain. They are:

• Location

• Quality

• Severity

• Timing, including onset, duration, and frequency

The effect of the symptom or condition on the patient’s life must be assessed. One can simply ask, “How has your problem interfered with your daily life?”

Pain

Pain is one of the most debilitating symptoms and has traditionally been underrecognized. Unrelieved pain is very common and is one of the most feared symptoms of illness. Surveys indicate that 20% to 30% of the U.S. population experiences acute or chronic pain, and it is the most common symptom experienced by hospitalized adults. More than 80% of patients with cancer and more than two thirds of patients dying of noncancer illnesses experience moderate to severe pain. There are approximately 75 million episodes of acute pain per year resulting from traumatic injuries and surgical procedures. Acute pain is caused by trauma or medical conditions, is usually brief, and abates with resolution of the injury. Chronic pain persists beyond the period of healing or is present for longer than 3 months.

The effect of pain on the quality of life is important to understand. Untreated or undertreated pain impairs physical and psychological health, functional status, and quality of life. In particular, pain may produce unnecessary suffering; decrease physical activity, sleep, and appetite, which further weakens the patient; may increase fear and anxiety that the end is near; may cause the patient to reject further treatment; may diminish the ability to work productively; may diminish concentration; may decrease sexual function; may alter appearance; and may diminish the enjoyment of recreation and social relationships. In addition, pain has been associated with increased medical complications, increased use of health care resources, decreased patient satisfaction, and unnecessary suffering. In the United States, the economic costs of undertreated pain approach $80 billion per year in treatment, compensation, and lost wages.

Because of health care providers’ lack of knowledge about analgesics, negative attitudes toward the use of pain control, and lack of understanding about addiction, and because of drug regulations and the cost of effective pain management, patients often suffer unnecessarily from inadequate pain control. A study of medical inpatients and the use of narcotic analgesics revealed that 32% of patients were continuing to experience “severe” distress despite the analgesic regimen, and 41% were in “moderate” distress. Breitbart and colleagues (1996) also revealed that pain was dramatically undertreated in ambulatory patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Of patients experiencing severe pain, only 7.3% received opioid analgesics at the recommended doses. Approximately 75% with severe pain received no opioid analgesics at all. The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment (1995) indicated that 50% of conscious patients who died in a hospital suffered “moderate-severe” pain during their last week of life.

Cleeland and associates (1997) reported that members of ethnic minority groups are likely to receive inadequate treatment for pain. Their study showed that minority patients were three times more likely to be undertreated for pain. Sixty-five percent of minority patients did not receive guideline-recommended analgesic prescriptions. Latino patients reported less pain relief than did African-American patients. Morrison and colleagues (2000) investigated the availability of commonly prescribed opioid analgesics in pharmacies in New York City. They found that 50% of a random sample of pharmacies surveyed did not stock sufficient medications to treat patients with severe pain adequately. Pharmacies in predominantly nonwhite areas were less likely to stock opioid analgesics than were pharmacies in predominantly white neighborhoods.

Whatever the cause of pain, health care providers must ask repeatedly about the presence of pain and the adequacy of its control:

“Have you had pain in the past week?”

“Tell me where your pain is located.”

“How has the pain affected your life?”

It is often useful with geriatric patients to say, “Many people have pain. Is there anything you want to tell me?” In cognitively impaired patients, the interviewer should ask about the real-time assessment of pain: pain now, not pain in the past 3 days.

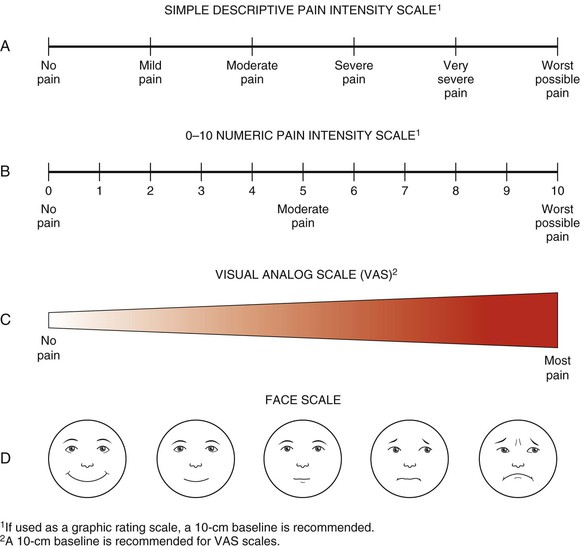

Patients must be able to assess pain with easily administered rating scales and should document the efficacy of pain relief at regular intervals after the initiation or modification of treatment. In addition, it is vital to teach patients and their families how to promote effective pain management at home. The interviewer should ask patients to quantify their pain and should try using some form of pain rating scale. There are four commonly used scales:

These scales are illustrated in Figure 1-1.

Past Medical History

The past medical history consists of the overall assessment of the patient’s health before the present illness. It includes all of the following:

General State of Health

As an introduction to the past medical history, the interviewer may ask, “How has your health been in the past?” If the patient does not elaborate about specific illnesses, but says only “Excellent” or “Fair,” for example, the interviewer might ask, “What does ‘excellent’ mean to you?” Direct questioning is appropriate and allows the interviewer to focus on pertinent points that need elaboration.

Past Illnesses

The record of past illnesses should include a statement of childhood and adult problems. Recording childhood illnesses is obviously more important for pediatric and young adult interviewees. All patients should nevertheless be asked about measles, mumps, whooping cough, rheumatic fever, chickenpox, polio, and scarlet fever. Older patients may respond, “I really don’t remember.” It is important to remember that a diagnosis given to the interviewer by a patient should never be considered absolute. Even if the patient was evaluated by a competent clinician in a reputable medical center, the interviewer may have misunderstood the information given.

Prior Injuries and Accidents

The patient should be asked about any prior injuries or accidents: “Have you ever been involved in a serious accident?” The type of injury and the date are important to record.

Hospitalizations

All hospitalizations must be indicated, if not already described. These include admissions for medical, surgical, and psychiatric illnesses. The interviewer should not be embarrassed to ask specifically about psychiatric illness, which is a medical problem. Interviewer embarrassment inevitably leads to patient embarrassment and reinforces the “shame” associated with psychiatric illness. Student interviewers should learn to ask direct questions in a sensitive manner. The interviewer might ask, “Have you ever been in therapy or counseling?” or “What nervous or emotional problems have you had?” Another way to ask about psychiatric hospitalizations is to ask, “Have you ever been hospitalized for a nonmedical or nonsurgical reason?”

Surgery

All surgical procedures should be specified. The indication, type of procedure, date, hospital, and surgeon’s name should be documented, if possible.

Allergies

All allergies should be described. These include environmental (including insects), ingestible, and drug-related reactions. The interviewer should seek specificity and verification of the patient’s allergic response. “How do you know you’re allergic?” “What kind of problem did you have when you took . . . ?” The specific symptoms of an allergy (e.g., rashes, nausea, itching, anaphylaxis) should be clearly indicated.

Immunizations

It is important to determine the immunization history of all patients. Tetanus and diphtheria immunity is present in fewer than 25% of adults, and fewer than 25% of targeted groups receive influenza vaccines yearly. Tetanus and diphtheria are preventable, and the current recommendation is to use the combined toxoid whenever either immunization is considered. Any patient who has never received this toxoid receives an initial injection and follow-up doses at 1 month and 6 to 12 months. A booster dose is required every 10 years.

All patients with chronic cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, renal, or hematologic disorders and patients with immunosuppression should be vaccinated yearly against influenza. Patients older than 65 years should also receive the vaccine.

Indications for the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine are similar to those for the influenza vaccine. In addition, patients with multiple myeloma, lymphoma, alcoholism, cirrhosis, and functional or anatomic asplenia should receive the vaccine. This vaccine usually provides lifelong immunity. Revaccination every 6 years is necessary only in asplenic patients because they are at high risk for pneumococcal infection.

Hepatitis A is one of the most common vaccine-preventable infections acquired during travel. Hepatitis A is a liver disease caused by the hepatitis A virus. Hepatitis A can affect anyone and is transmitted by the fecal-oral route. In the United States, hepatitis A can occur in situations ranging from isolated cases of disease to widespread epidemics. Good personal hygiene and proper sanitation can help prevent hepatitis A. Vaccines are also available for long-term prevention of hepatitis A virus infection in persons 12 months of age and older. The first dose of hepatitis A vaccine should be administered as soon as travel to countries with high or intermediate endemicity is considered. One month after receiving the first dose of monovalent hepatitis A vaccine, 94% to 100% of adults and children have protective concentrations of antibody. The final dose in the hepatitis A vaccine series is necessary to promote long-term protection. Immune globulin is available for short-term prevention of hepatitis A virus infection in individuals of all ages.

Hepatitis B vaccine should be given to all health care providers, staff of institutions for developmentally disabled patients, intravenous drug abusers, patients with multiple sexual partners, hemodialysis patients, sexual partners of hepatitis B carriers, and patients with hemophilia. Complete immunization necessitates three injections: an initial dose and follow-up doses at 1 month and at 6 to 12 months. Booster doses are not required. For best results, persons at high risk of exposure (especially medical, dental, and nursing students) should receive immunization before possible exposure.

Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) vaccine is now used routinely in children to prevent invasive H. influenzae diseases. In 2005, Hib was estimated to have caused 3 million cases of serious disease, notably pneumonia and meningitis, and 450,000 deaths in young children. Meningitis and other serious infections caused by Hib disease can lead to brain damage or death. Hib disease is preventable by immunizing all children younger than 5 years with an approved Hib vaccine. Several Hib vaccines are available. The general recommendation is to immunize children with a first dose at 2 months of age and to follow with additional doses according to the schedule for the vaccine being used. Three to four doses are needed, depending on the brand of Hib vaccine used. Hib vaccine should never be given to a child younger than 6 weeks, because this might reduce his or her response to subsequent doses.

Between 1991 and 1992, there was a 75% decrease in the number of cases of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR), presumably because of the use of the MMR vaccine. This vaccine is now typically given in childhood, but it should also be given to adult health care providers who have not had the diseases. Because the vaccine contains a live virus, it should not be given to pregnant patients, those with generalized malignancies, those receiving steroid therapy, those with active tuberculosis, or those receiving antimetabolites.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices annually reviews the recommended adult immunization schedule to ensure that the schedule reflects the current recommendations for the licensed vaccines. It is advisable for the health care worker to review these guidelines regularly.

Substance Abuse

A careful review of any substance abuse by the patient is included in the past medical history. Substance abuse includes cigarette smoking and the use of alcohol and recreational drugs. In the United States in 2007, an estimated 46 million people were smokers. Approximately 23% of men and 19% of women smoke. As many as 30% of all deaths related to coronary heart disease in the United States each year are attributable to cigarette smoking; the risk is strongly dose-related. Smoking also nearly doubles the risk of ischemic stroke. Smoking acts synergistically with other risk factors, substantially increasing the risk of coronary disease. Smokers are also at increased risk for peripheral vascular disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, and many other chronic diseases. Cigarette smoking is the single most alterable risk factor contributing to premature morbidity and mortality in the United States, accounting for approximately 430,000 deaths annually.

The interviewer should always ask whether the patient smokes and for how long: “Do you use nicotine in any form: cigarettes, cigars, pipes, chewing tobacco?” A pack-year is the number of years a patient has smoked cigarettes multiplied by the number of packs per day. A patient who has smoked 2 packs of cigarettes a day for the past 25 years has a smoking history of 50 pack-years. If the patient answers that he or she does not smoke now, the interviewer should inquire whether the patient ever smoked. If the patient has quit smoking, indicate for how long.

It has been estimated that the incidence of hazardous alcohol drinking in the United States ranges from 4% to 5% among women and 14% to 18% among men. In primary care settings, the prevalence rates range from 9% to 34% for hazardous drinking. Although studies have shown the beneficial effects of moderate alcohol consumption (one to two drinks daily), these effects are lost at higher doses. Heavy alcohol consumption is associated with many medical problems (e.g., hypertension, decreased cardiac function, arrhythmias, hemorrhagic stroke, ischemic stroke, liver disease, increased risk of breast cancer), as well as behavioral and psychiatric problems. According to the American Psychiatric Association and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, “moderate drinking” for men is defined as less than 2 drinks per day; for women and persons older than 65 years, it is defined as less than 1 drink per day.