The Intensive Care Unit

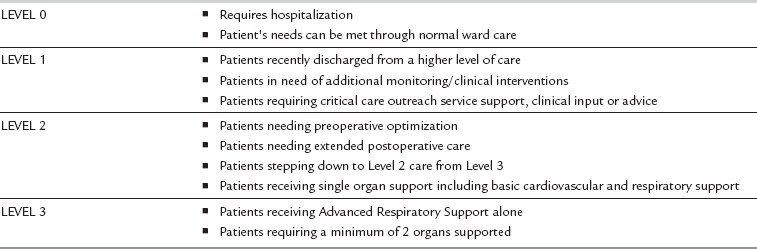

The key components of intensive care are resuscitation and stabilization, physiological optimization to prevent organ failure, support of the failing organ systems and recognition of futility of treatment. The Department of Health NHS Executive defines intensive care as ‘a service for patients with potentially recoverable conditions who can benefit from more detailed observation and treatment than can safely be provided in general wards or high dependency areas’. Levels of care within the hospital can be described from level 0 (ward-based care) to level 3 (patients requiring advanced respiratory support alone or a minimum of 2 organs being supported) (Table 45.1). There is now a move towards a comprehensive critical care system, where the needs of all patients who are critically ill, rather than just those who are admitted to designated intensive care or high dependency beds, are met with consistency.

STAFFING AN INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

The Microbiologist

Critically ill patients are immunocompromised as a result of the underlying pathological process, the impact of treatments (such as steroids) and the presence of surgical/traumatic wounds, multiple vascular catheters and other invasive tubing. This predisposes them to hospital-acquired infections. Prolonged use of broad-spectrum antibiotics encourages the development of resistant pathogens and overgrowth of other organisms. In order to effectively treat sepsis and prevent resistance, there is usually a nominated microbiologist, who is familiar with the flora and resistance patterns of the unit, and who visits the ICU daily to advise on microbiology results and antibiotic therapy. It is also essential to adhere to local policies aimed at reducing cross infection and minimizing the number of hospital-acquired infections. The National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) also has a number of helpful guidelines for personnel working on ICU (www.npsa.nhs.uk).

OUTREACH/FOLLOW-UP

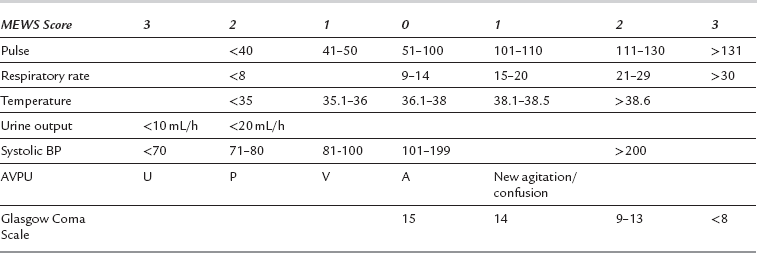

A number of scoring systems based on abnormal physiological variables, such as the modified early warning score (MEWS) (Table 45.2), can be recorded by ward staff; the outreach team can be contacted accordingly once a trigger score has been reached. Care needs to be taken with younger fitter patients, who have good physiological reserve and who may not deteriorate in terms of MEWS score until a peri-arrest situation develops (e.g. in presence of bleeding or severe sepsis). Children, obstetric, neurological, renal and other sub-specialty groups have adapted scores to allow for altered background physiological status.

ADMISSION TO THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

Assessment of Patients

Limbs/Skin and Wounds

Surgical wounds and trauma sites should be inspected for adequate healing or infection.

MONITORING IN ICU

Invasive Monitoring

Pulmonary Artery Catheter

Pulse Contour Analysis: The peripheral arterial pulse waveform is a function of the cardiac output, the peripheral vascular resistance, peripheral vascular compliance and the arterial pressure. If the cardiac output is measured for a given peripheral arterial waveform, then after calibration, changes in the peripheral pulse waveform can be used to calculate changes in the cardiac output. To calibrate the system an indicator is injected into a venous catheter and is detected by an arterial line producing a standard dilutional CO measurement. Systems such as PiCCO and LiDCO use thermodilution and lithium respectively as the indicators. Aside from cardiac output, stroke volume and systemic vascular resistance, other variables available with PiCCO include global end diastolic volume (cardiac preload) and intrathoracic blood volume. Dynamic measures, using heart–lung interactions to predict fluid responsiveness, can also be widely determined using beat to beat cardiac output monitoring.

INSTITUTION OF INTENSIVE CARE

The Respiratory System

Respiratory failure is one of the commonest reasons for admission to the ICU (Table 45.3). It may be the primary reason for admission or a feature of a non-respiratory pathological process, e.g. adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in sepsis. Respiratory failure may encompass hypoxaemia with a normal/low PaCO2 (type 1) or a combination of hypoxaemia and high PaCO2 (type 2).

TABLE 45.3

| Reduced central drive | Brainstem injury/CVA Drug effects, e.g. opioids Metabolic encephalopathy |

| Airway obstruction | Tumour Infection Sleep apnoea Foreign body |

| Lung pathology | Asthma COPD Pneumonia Fibrosis ALI/ARDS Lung contusion |

| Neuromuscular defects | Spinal cord lesion Phrenic nerve disruption Myasthenia gravis Guillain–Barré syndrome Critical illness polyneuropathy |

| Musculoskeletal | Trauma Severe scoliosis |

Assessment of the Patient with Respiratory Failure

Clinical assessment is often the most rapid way to evaluate the patient with respiratory failure (Table 45.4):

TABLE 45.4

Signs of Impending Respiratory Arrest

Marked tachypnoea, or hypoventilation, patient exhausted

Use of accessory muscles

Cyanosis and desaturation, especially if on supplemental oxygen

Tachycardia or bradycardia if peri-arrest

Sweaty, peripherally cool/clammy

Mental changes, confusion and leading to coma in extreme conditions

Can patient talk in sentences?

Can patient talk in sentences?

Are they awake and orientated?

Are they awake and orientated?

What is the pulse, BP and respiratory rate?

What is the pulse, BP and respiratory rate?

Is the patient using accessory muscles of respiration?

Is the patient using accessory muscles of respiration?

Can they cough effectively to clear secretions?

Can they cough effectively to clear secretions?

Do they appear exhausted? Exhaustion and impending respiratory failure that is likely to require ventilatory support is an end-of-bed diagnosis.

Do they appear exhausted? Exhaustion and impending respiratory failure that is likely to require ventilatory support is an end-of-bed diagnosis.

Management of Respiratory Failure

Other therapies may be useful such as bronchodilators, steroids, diuretics and physiotherapy in the first instance depending on the mechanism of respiratory failure. Many patients may be dehydrated due to poor fluid intake and increased losses and will require IV fluids. If there is no improvement over time, additional respiratory support may be necessary (Table 45.5). Options include:

TABLE 45.5

Indications for Ventilatory Support

Indications for ventilatory support in respiratory failure

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP): CPAP is provided via a tightly fitting mask or hood. A high gas flow (greater than the patient’s peak inspiratory flow rate) is required to keep the positive pressure set by the expiratory valve (+ 5–10 cmH2O) almost constant throughout the respiratory cycle. CPAP increases functional residual capacity (FRC), reduces alveolar collapse and improves oxygenation but it requires a co-operative patient, with no facial injuries. It does not generally help the patient with type 2 respiratory failure. There is a small risk of aspiration as a result of stomach distension.

Non-Invasive Positive Pressure Ventilation (NIPPV or NIV): Non-invasive techniques have been successfully used to treat acute exacerbations in patients with COPD, in the management of pulmonary oedema and as a weaning aid. Biphasic or bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP or BPAP) is a common form where a set inspiratory pressure enhances the patient’s own respiratory effort to increase achievable tidal volume and the set expiratory pressure is analogous to CPAP.

Mechanical Ventilation

Tracheal Intubation: To enable mechanical ventilation to be carried out effectively, a cuffed tube must be placed in the trachea either via the mouth or nose, or directly through a tracheostomy stoma. In the emergency situation, an orotracheal tube is usually inserted. If the patient is conscious, anaesthesia should be induced carefully with an appropriate dose of an i.v. anaesthetic induction agent and neuromuscular blocker. The full range of adjuncts for difficult intubation should be available.

After neuromuscular blockade has been produced, the tube should be inserted by the route which is associated with the least delay.

After neuromuscular blockade has been produced, the tube should be inserted by the route which is associated with the least delay.

If the patient is unconscious and the victim of blunt trauma, when cervical spine injury is a possibility, the cervical spine should be immobilized during intubation using manual in-line immobilization.

If the patient is unconscious and the victim of blunt trauma, when cervical spine injury is a possibility, the cervical spine should be immobilized during intubation using manual in-line immobilization.

Cricoid pressure should be applied to minimize the risk of aspirating gastric contents.

Cricoid pressure should be applied to minimize the risk of aspirating gastric contents.

A sterile, disposable plastic tube with a low-pressure cuff should be used. The tube should be inserted such that the top of the cuff lies not more than 3 cm below the vocal cords.

A sterile, disposable plastic tube with a low-pressure cuff should be used. The tube should be inserted such that the top of the cuff lies not more than 3 cm below the vocal cords.

The head should be placed in a neutral or slightly flexed position (on one pillow) after tracheal intubation and a chest X-ray taken to ensure that the tip of the tube lies at least 5 cm above the carina.

The head should be placed in a neutral or slightly flexed position (on one pillow) after tracheal intubation and a chest X-ray taken to ensure that the tip of the tube lies at least 5 cm above the carina.

Sedation and Analgesia: Once tracheal intubation has been performed, some amount of sedative drugs will be required to tolerate the tube and facilitate effective mechanical ventilation. The balance between providing adequate sedation to permit patient co-operation with organ system support and oversedation, which leads to a number of detrimental effects (Table 45.6) is often difficult. The aims of sedation include patient comfort and analgesia, minimizing anxiety, and to allow a calm co-operative patient who is able to sleep when undisturbed and able to tolerate appropriate organ support. Patients must not be paralysed and awake but the efficiency of supportive care will be reduced in the patient who is agitated and distressed. Clearly the patient’s needs for sedation will alter with changes in clinical condition and requirements for care, so regular review and sedation scoring are helpful (Table 45.7).

TABLE 45.6

Problems and Potential Consequences of Excessive Sedation in ICU

| Problem | Potential consequence |

| Accumulation with prolonged infusion | Delayed weaning from supportive care |

| Detrimental effect on cardiovascular system | Increased requirement for vasoactive drugs |

| Detrimental effect on pulmonary function | Increased VQ mismatch |

| Tolerance | Withdrawal on stopping sedation |

| No REM sleep | Sleep deprivation and ICU psychosis |

| Reduced intestinal motility | Impairment of enteral feeding |

| Potential effects on immune/endocrine function | Drugs such as opioids may have a role in immunomodulation and risk of infection |

| Adverse effects of specific drugs | e.g. propofol infusion syndrome, with cardiovascular collapse |

TABLE 45.7

Sedation Scoring Using the Ramsay Sedation Scale

Ramsay Sedation Scale

An Overview of Modes of Ventilation

Volume Controlled Ventilation: The simplest form of volume controlled ventilation is controlled mandatory ventilation (CMV). The patient’s lungs are ventilated at a preset tidal volume and rate (for example, tidal volume 500 mL and rate 12 breaths min− 1). The tidal volume delivered is therefore predetermined and the peak pressure required to deliver this volume varies depending upon other ventilator settings and the patient’s pulmonary compliance. A major disadvantage of CMV is that high peak airway pressures may result and this can lead to lung damage or barotrauma. Therefore it is only really suitable for patients who are heavily sedated and/or paralysed and who are making no respiratory effort.

Pressure Controlled Ventilation: Pressure controlled modes of ventilation are commonly used, and are preferred in patients with poor pulmonary compliance. A peak inspiratory pressure is set and so tidal volume delivered is a function of the peak pressure, the inspiratory time and the patient’s compliance. By using lower peak pressures and slightly longer inspiratory times the risks of barotrauma can be reduced. As the patient’s condition improves and lung compliance increases, the tidal volume achieved for the same settings will increase and the inspiratory pressure can therefore be reduced. Biphasic or bi-level positive airway pressure (BIPAP) is a variation of pressure controlled ventilation which permits spontaneous breaths by the patient at all times during the ventilator cycle.

Synchronized Intermittent Mandatory Ventilation (SIMV): Modes of ventilation have been developed which allow preservation of the patient’s own respiratory efforts by detecting an attempt by the patient to breathe in and synchronizing the mechanical breath with spontaneous inspiration; this technique is termed synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV). If no attempt at inspiration is detected over a period of some seconds then a mandatory breath is delivered to ensure that a safe total minute volume is provided.

Pressure Support Ventilation (PSV)/Assisted Spontaneous Breathing (ASB): Breathing through a ventilator can be difficult because respiratory muscles may be weak and ventilator circuits and tracheal tubes provide significant resistance to breathing. During PSV the ventilator senses a spontaneous breath and augments it by addition of positive pressure. This reduces the patient’s work of breathing and increases the tidal volume. Pressure support is usually set at 15–20 cmH2O in the first instance and can be reduced as the patient’s condition improves. It is best not to remove pressure support completely, however, because of the internal resistance of the ventilator and its connections. SIMV and PSV require a method of detecting the patient’s own respiratory effort, in order to trigger the appropriate ventilator response. This is achieved by flow sensors detecting small changes in gas flow within the circuit.

Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP): PEEP has the advantage of alveolar recruitment and maintenance of functional residual capacity, which will improve lung compliance. Some patients, e.g. those with expiratory airflow limitation can develop air trapping and a degree of so-called ‘intrinsic PEEP’. Modern ventilators are capable of calculating this and it is important to consider it when setting levels of externally applied extrinsic PEEP in this subset of patients, as there is a potential risk of sustained lung hyperinflation if external PEEP is set above the level of intrinsic PEEP. While PEEP is beneficial for the vast majority of mechanically ventilated patients, it can reduce venous return and cardiac output so caution must be exercised at higher levels.

Problem Solving in Ventilated Patients

Ventilation Strategies: The concept of ventilator-induced lung injury by overdistension, shear stress injury and oxygen toxicity has been increasingly recognized over the past few years and a number of strategies have been put into place to reduce such damage:

Limiting peak pressure to 35 cmH2O.

Limiting peak pressure to 35 cmH2O.

Limiting tidal volume to 6 mL kg–1.

Limiting tidal volume to 6 mL kg–1.

Acceptance of higher than normal PaCO2 levels (6–8 kPa), so-called ‘permissive hypercapnia’.

Acceptance of higher than normal PaCO2 levels (6–8 kPa), so-called ‘permissive hypercapnia’.

Acceptance of PaO2 7–8 kPa, SaO2 > 90%.

Acceptance of PaO2 7–8 kPa, SaO2 > 90%.

Use of higher levels of PEEP to improve alveolar recruitment.

Use of higher levels of PEEP to improve alveolar recruitment.

Use of longer inspiratory times.

Use of longer inspiratory times.

Use of ventilation modes which allow and support spontaneous respiratory effort.

Use of ventilation modes which allow and support spontaneous respiratory effort.

The acceptable threshold for such values is not known and has to be considered on an individual patient basis.

The acceptable threshold for such values is not known and has to be considered on an individual patient basis.

Other Aspects of Ventilation

High-Frequency Oscillation: In patients with poor compliance, high frequency oscillatory ventilation is a means of reducing transpulmonary pressure while providing adequate gas exchange. Small tidal volumes (lower than deadspace) are generated by an oscillating a diaphragm across the open airway resulting in a sinusoidal or square gas flow pattern. Peak airway pressure is reduced but mean airway pressure is increased allowing for alveolar recruitment and improved oxygenation. Oxygenation certainly improves, but outcomes are currently under study.

Prone Positioning: Another strategy to improve ventilation is to place the patient in the prone position. Recent work has suggested that the improvement is related to changes in regional pleural pressure. This may result partly from the decreased volume of lung compressed by the mediastinal structures when in the prone position. In the prone position, pleural pressure becomes more uniform and reduces ventilation–perfusion mismatch. The technique is very labour-intensive; four people are needed to turn the patient and great care is required to ensure that the airway and vascular catheters/cannulae are not dislodged. A recent multicentre European trial has shown that although oxygenation is improved in responders, the effect does not result in improved survival to discharge.

Nitric Oxide: Nitric oxide (NO) is an ultra-short-acting pulmonary vasodilator. When added to the respiratory gases (5–20 parts per million), it is delivered preferentially to the recruited alveoli and results in pulmonary vasodilation in areas of well ventilated lung. Blood is diverted away from poorly ventilated areas and ventilation–perfusion mismatch is reduced. It is rapidly inactivated by haemoglobin and so vasodilator effects are limited to the pulmonary circulation.

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is a possible final option if other conventional techniques of providing ventilatory support have failed. Partial cardiopulmonary venovenous bypass is initiated using heparin-bonded vascular catheters, and extracorporeal oxygenation and carbon dioxide removal are achieved using a membrane oxygenator. A low-volume, low-pressure, low-frequency regimen of ventilation is continued to allow the lungs to recover. Results of a recent trial (CESAR) appear favourable in selected patients but the trial design has been subject to criticism and in the UK the availability of ECMO in adults is limited to very few centres, so the additional risks, benefits and timing of transfer of the severely hypoxaemic patient must be considered. Smaller more portable lung assist devices are under evaluation and may be available for use in the future.

Weaning from Mechanical Ventilation

Be awake and co-operative with intact neuromuscular and bulbar function

Be awake and co-operative with intact neuromuscular and bulbar function

Have stable cardiovascular function with minimal requirements for inotropic or vasopressor drugs

Have stable cardiovascular function with minimal requirements for inotropic or vasopressor drugs

Not have a marked ongoing respiratory metabolic acidosis

Not have a marked ongoing respiratory metabolic acidosis

Have inspired oxygen requirements < 50%

Have inspired oxygen requirements < 50%

Be able to generate a vital capacity 10 mL kg–1, tidal volumes > 5 mL kg–1 and a negative inspiratory pressure > 20 cmH2O

Be able to generate a vital capacity 10 mL kg–1, tidal volumes > 5 mL kg–1 and a negative inspiratory pressure > 20 cmH2O

Have low sputum production and be able to generate a good cough

Have low sputum production and be able to generate a good cough

Cardiovascular System

Basic Applied Cardiovascular Physiology

The volume of oxygen carried by 1 g of haemoglobin is 1.34 mL.

Optimization of the Cardiovascular Status

Examples of positive inotropes can be found in Table 45.8 and further details are found in Chapter 8. Initiation of these drugs requires central venous access, although low dose phenylephrine can be infused through a peripheral cannula.

TABLE 45.8

Positive Inotropic Drugs Commonly Used in ICU

| Drug | Mode of Action |

| Dobutamine | Increases contractility, and produces peripheral vasodilatation. |

| Dopexamine | Vasodilator at low doses, with reflex tachycardia. Positive inotropic effects seen at higher doses. |

| Dopamine | Vasodilatation at low doses via dopamine receptors. At higher doses, inotropic and vasoconstrictor effects appear. |

| Adrenaline | Positive inotropic and vasoconstrictor effects. |

| Milrinone, Enoximone | Positive inotropic and vasodilator effects by inhibition of phosphodiesterase enzymes. |

| Levosimendan | Positive inotrope which increases myocardial response to calcium. |

Cardiac rhythm disturbances are common in ICU patients. Ensure that general resuscitation measures are adequate and treat any electrolyte disturbances (especially of potassium and magnesium). Specific treatment may be required, e.g. amiodarone or digoxin for supraventricular tachycardia (see Ch 8). Other cardiovascular conditions to consider include myocardial ischaemia, cardiac failure and cardiogenic shock.

Gastrointestinal System

Nutrition

Parenteral Feeding: If enteral feeding is contraindicated, e.g. for surgical reasons, or cannot be established successfully, then parenteral (i.v.) feeding is initiated. It requires dedicated central venous access and advice from the nutrition team, so that complications relating to overfeeding, hyperglycaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, uraemia, metabolic acidosis and electrolyte imbalance can be avoided. Hepatobiliary dysfunction (including derangement of liver enzymes and fatty infiltration of the liver) may also occur and is usually caused by the patient’s underlying condition and overfeeding.

Refeeding Syndrome: Refeeding syndrome results from shifts in fluid and electrolytes that may occur when a chronically malnourished patient receives artificial feeding, either parenterally or enterally. It results in hypophosphataemia, but may also feature abnormal sodium and fluid balance as well as changes in glucose, protein and fat metabolism and is potentially fatal. Thiamine deficiency, hypokalaemia and hypomagnesaemia may also be present. Patients at high risk include those chronically undernourished and those who have had little or no energy intake for more than 10 days. Ideally these patients require refeeding at an initially low level of energy replacement alongside vitamin supplementation.

Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis: Early enteral feeding promotes and maintains gastric mucosal blood flow, provides essential nutrients to the mucosa and reduces the incidence of stress ulcers. If enteral feeding cannot be established, alternative prophylactic measures need to be prescribed, commonly ranitidine or omeprazole.

Blood Glucose: Modest (not tight) glucose control is advocated for ICU patients and this is usually achieved by an infusion of insulin running alongside a dextrose-based infusion, to allow titration of blood glucose concentrations. High blood glucose worsens outcomes in brain injury and cardiac ischaemia. However, a recent large study has shown that a regimen of tight glycaemic control results in a worse outcome, thought to be primarily due to high rates of significant hypoglycaemia. Greater emphasis should probably be placed on avoiding glucose variability and easier continuous bedside blood glucose monitoring.

Renal Dysfunction

Acute kidney injury is defined as an abrupt (within 48 hours) reduction in kidney function, with the diagnosis made on the specific changes from baseline in patients who have achieved an optimal state of hydration (Table 45.9).

TABLE 45.9

Diagnosis of Acute Kidney Injury

| AKI Stage | Serum Creatinine Criteria | Urine Output Criteria |

| 1 | Increase in serum creatinine ≥ 0.3 mg dL–1 or Increase to ≥ 150–200% from baseline |

< 0.5 mL kg–1 h–1 for > 6 h |

| 2 | Increase in serum creatinine > 200–300% from baseline |

< 0.5 mL kg–1 h–1 for > 12 h |

| 3 | Increase in serum creatinine to > 300% from baseline (or serum creatinine ≥ 4 mg dL–1) with an acute increase ≥ 0.5 mg dL–1, or receiving renal replacement therapy |

< 0.3 mL kg–1 h–1 for 24 h Or anuria for 12 h |

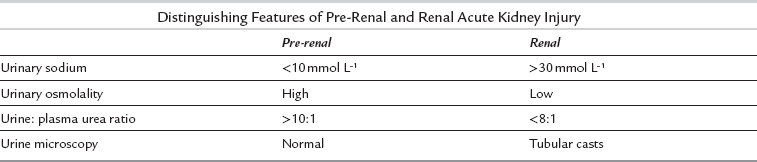

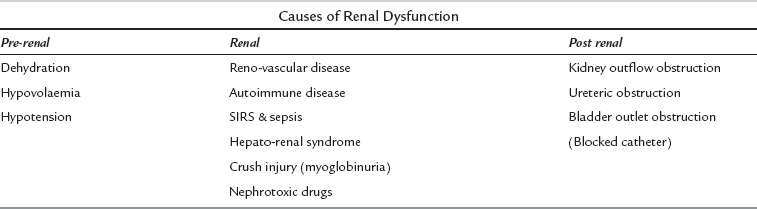

This classification takes into account the significance of even small increases in serum creatinine, given the recognized associated adverse outcomes. When managing a patient with acute kidney injury, focus the history and examination to distinguish potential causes (Table 45.10). These are classically distinguished as prerenal, renal and postrenal causes, although in many patients the cause of acute kidney injury is multifactorial. A sudden cessation of urine output should be assumed to be caused by obstruction until proved otherwise. Ensure the patient is adequately hydrated.

TABLE 45.10

Causes of Renal Dysfunction or Acute Kidney Injury in the ICU. Several Potential Causes Often Co-Exist in ICU Patients

In most cases of AKI the primary cause is prerenal, but up to 10% of cases will have other significant pathologies. Serial U & Es are essential, while urine tests can be helpful (unless the patient has received diuretics) in distinguishing pre-renal from renal failure (Table 45.11).

Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT)

Continuous renal replacement therapy is used in intensive care units because the gradual correction of biochemical abnormalities and removal of fluid results in greater haemodynamic stability, compared to intermittent haemodialysis (Table 45.12).

TABLE 45.12

Indications for Renal Replacement Therapy

| Classical Indications | Alternative Indications |

| Volume overload | Endotoxic shock |

| Hyperkalaemia (K+ > 6.5) | Severe dysnatraemia (Na+ < 115 or > 165 mmol L–1) |

| Metabolic acidosis (pH < 7.1) | Plasmapheresis |

| Symptomatic uraemia (encephalopathy, pericarditis, bleeding) | |

| Dialysable toxins (lithium, aspirin, methanol, ethylene glycol, theophylline) |

Vascular Access for Renal Replacement Therapy

Neurological System

Exclude and treat other life threatening injuries elsewhere (e.g. chest and abdominal bleeding)

Exclude and treat other life threatening injuries elsewhere (e.g. chest and abdominal bleeding)

Secure the airway definitively

Secure the airway definitively

Staff should be trained in airway and head injury management

Staff should be trained in airway and head injury management

End-tidal CO2 should be maintained at 4–4.5 kPa on a transport ventilator

End-tidal CO2 should be maintained at 4–4.5 kPa on a transport ventilator

SpO2 and arterial gases should be checked to ensure adequate oxygenation

SpO2 and arterial gases should be checked to ensure adequate oxygenation

Blood pressure and adequate fluids and vasopressors should be available

Blood pressure and adequate fluids and vasopressors should be available

Brain CT imaging should be completed and hard/electronic copies available

Brain CT imaging should be completed and hard/electronic copies available

Transfer should be complete within 4 h – no inappropriate delays, e.g. for central venous access.

Transfer should be complete within 4 h – no inappropriate delays, e.g. for central venous access.

OTHER ASPECTS OF INTENSIVE CARE

Healthcare-Associated Infection (HAI)

Care Bundles

low tidal volumes (6 mL per kg predicted body weight)

low tidal volumes (6 mL per kg predicted body weight)

capped plateau airway pressure (30 cmH2O)

capped plateau airway pressure (30 cmH2O)

sedation holds and use of sedation scores. The practice of interrupting continuous sedative infusions on a daily basis to allow intermittent decreased sedation, has been shown to reduce length of ICU stay

sedation holds and use of sedation scores. The practice of interrupting continuous sedative infusions on a daily basis to allow intermittent decreased sedation, has been shown to reduce length of ICU stay

permissive hypercapnia (accepting a PaCO2 above normal to allow pressure limitation and low plateau airway pressures)

permissive hypercapnia (accepting a PaCO2 above normal to allow pressure limitation and low plateau airway pressures)

semi-recumbent positioning (head up by 45° unless contraindicated) during ventilation to reduce the incidence of ventilator-induced pneumonia

semi-recumbent positioning (head up by 45° unless contraindicated) during ventilation to reduce the incidence of ventilator-induced pneumonia

lung recruitment by PEEP to prevent alveolar collapse at end-expiration

lung recruitment by PEEP to prevent alveolar collapse at end-expiration

avoidance of neuromuscular blocking drugs may reduce the incidence of skeletal muscle weakness associated with critical illness

avoidance of neuromuscular blocking drugs may reduce the incidence of skeletal muscle weakness associated with critical illness

ETHICAL ISSUES IN ICU

As in all medical practice, four ethical principles can be applied to the ICU patient.

OUTCOME AFTER INTENSIVE CARE

There are a number of scoring systems in use:

APACHE II. The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation score takes into account pre-existing comorbidities as well as acute physiological disturbance and correlates well with the risk of death in an intensive care population, but not on an individual basis. However, it remains one of the more widely used tools and a score is calculated on:

APACHE II. The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation score takes into account pre-existing comorbidities as well as acute physiological disturbance and correlates well with the risk of death in an intensive care population, but not on an individual basis. However, it remains one of the more widely used tools and a score is calculated on:

APACHE III has superseded the APACHE II score, with the variations in the physiological components.

APACHE III has superseded the APACHE II score, with the variations in the physiological components.

Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS). This scoring system uses 12 physiological variables assigned a score according to the degree of derangement.

Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS). This scoring system uses 12 physiological variables assigned a score according to the degree of derangement.

Therapeutic Intervention Score System (TISS). A score is given for each procedure performed on the ICU, so that sicker patients require more procedures. However, procedures undertaken are both clinician and unit specific and so TISS is less useful for comparing outcomes between different units.

Therapeutic Intervention Score System (TISS). A score is given for each procedure performed on the ICU, so that sicker patients require more procedures. However, procedures undertaken are both clinician and unit specific and so TISS is less useful for comparing outcomes between different units.

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA). This tracks changes in the patient’s condition regarding their respiratory, cardiovascular, hepatic, neurological, renal and coagulation status.

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA). This tracks changes in the patient’s condition regarding their respiratory, cardiovascular, hepatic, neurological, renal and coagulation status.

DEATH IN THE ICU

Futility and withdrawal

Vasopressor and inotropic drug support are reduced and subsequently discontinued.

Vasopressor and inotropic drug support are reduced and subsequently discontinued.

Sedation may be increased and inspired oxygen concentration can be reduced to room air.

Sedation may be increased and inspired oxygen concentration can be reduced to room air.

Other supportive treatments such as renal replacement therapy are removed.

Other supportive treatments such as renal replacement therapy are removed.

Assisted ventilation may be reduced and tracheal extubation carried out.

Assisted ventilation may be reduced and tracheal extubation carried out.

Feeding and hydration are generally continued if practical and not requiring extra invasive instrumentation.

Feeding and hydration are generally continued if practical and not requiring extra invasive instrumentation.

Death may occur quickly or be prolonged over hours or days depending on the clinical situation.

Death may occur quickly or be prolonged over hours or days depending on the clinical situation.

Once a patient has died, confirmation of death is required. Although in the UK there is no actual legal definition of death, it should be identified as the irreversible loss of the capacity for consciousness, combined with the irreversible loss of the capacity to breathe. (See a code of practice for the diagnosis and confirmation of death: www.aomrc.org.uk.)

Sudden, unexpected, suspicious, violent or unnatural deaths

Sudden, unexpected, suspicious, violent or unnatural deaths

Deaths due to alcohol or drugs

Deaths due to alcohol or drugs

Depending on the circumstance, a post mortem may be necessary.

Brainstem Death

Preconditions for brainstem death testing include:

the presence of identifiable pathology causing irreversible damage

the presence of identifiable pathology causing irreversible damage

the patient must be deeply unconscious (hypothermia, depressant drugs and potentially reversible circulatory, metabolic, endocrine disturbances must all be excluded as a cause of the conscious level)

the patient must be deeply unconscious (hypothermia, depressant drugs and potentially reversible circulatory, metabolic, endocrine disturbances must all be excluded as a cause of the conscious level)

Pupils must be fixed and not responsive to light (cranial nerves II, III)

Pupils must be fixed and not responsive to light (cranial nerves II, III)

There must be no corneal reflex (cranial nerves V, VII)

There must be no corneal reflex (cranial nerves V, VII)

Vestibulo-ocular reflexes are absent, i.e. no eye movement occur following injection of ice cold saline into the auditory meatus (cranial nerves, III, IV, VI, VIII)

Vestibulo-ocular reflexes are absent, i.e. no eye movement occur following injection of ice cold saline into the auditory meatus (cranial nerves, III, IV, VI, VIII)

No facial movement will occur in response to supra-orbital pressure (cranial nerves V, VII)

No facial movement will occur in response to supra-orbital pressure (cranial nerves V, VII)

No gag reflex to posterior pharyngeal wall stimulation (cranial nerve IX)

No gag reflex to posterior pharyngeal wall stimulation (cranial nerve IX)

No cough or other reflex in response to bronchial stimulation with a suction catheter passed down the tracheal tube (cranial nerve X)

No cough or other reflex in response to bronchial stimulation with a suction catheter passed down the tracheal tube (cranial nerve X)

No respiratory movements will occur when disconnected from the ventilator, hypoxia is prevented with pre-oxygenation and oxygen insufflation via a tracheal catheter and PaCO2 should be > 6.65 kPa.

No respiratory movements will occur when disconnected from the ventilator, hypoxia is prevented with pre-oxygenation and oxygen insufflation via a tracheal catheter and PaCO2 should be > 6.65 kPa.

DISCHARGE FROM INTENSIVE CARE

Follow-Up Clinics

Critical illness neuropathy/myopathy,

Critical illness neuropathy/myopathy,

Respiratory dysfunction – breathlessness is a common symptom

Respiratory dysfunction – breathlessness is a common symptom

Cardiac problems – MI or cardiomyopathy

Cardiac problems – MI or cardiomyopathy

Swallowing difficulties and tracheal stenosis post-intubation/tracheostomy

Swallowing difficulties and tracheal stenosis post-intubation/tracheostomy

Sexual dysfunction, affective disorders and post traumatic stress disorder

Sexual dysfunction, affective disorders and post traumatic stress disorder

Quality of life may significantly decrease following illness

Quality of life may significantly decrease following illness

Brooks A., Girling K., Riley B., et al, eds. Critical care for postgraduate trainees. London: Hodder Arnold, 2005.

Hillman, K., Bishop, G. Clinical intensive care, second ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

Hinds, C.J., Watson, J.D. Intensive care: a concise textbook, third ed. London: Saunders; 2008.

Webb, A.R., Shapiro, M., Singer, M., Suter, P. Oxford textbook of critical care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999.

Whiteley, S., Bodenham, A., Bellamy, M. Churchill Livingstone’s pocketbook of intensive care, third ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.