Chapter 4 The integumentary, skeletal and muscular systems

The integumentary system

The skin

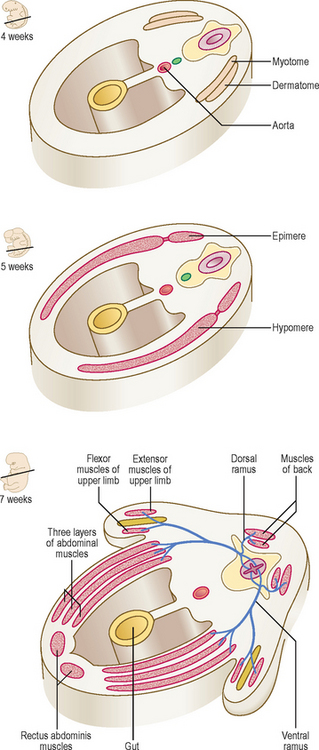

By the end of the first month the single layer of ectodermal cells divide, forming a superficial layer of cells known as the periderm and a basal layer. The basal layer becomes the stratum germinativum which produces all the definitive layers of the epidermis (Fig. 4.1A, B). The cells of the periderm become keratinized, and are continuously lost in the amniotic fluid during fetal life. In a newborn infant, the sloughed cells of the periderm mix with the skin secretions to form the vernix caseosa that covers the entire skin. Later in fetal life, the peridermal cells are replaced by the stratum corneum and the melanocytes derived from the neural crest migrate into the epidermis (Fig. 4.1B, C).

The dermis is derived from two sources: the somatic layer of the lateral plate of mesoderm and the dermatomes of the somites. The capillary network develops in the dermis to nourish the epidermis, and by 9 weeks, the sensory nerve endings grow into the dermis and epidermis. By 12 weeks, the outer layer of dermis projects into the overlying epidermis as dermal papillae (Fig. 4.1B).

The hairs and glands of the skin

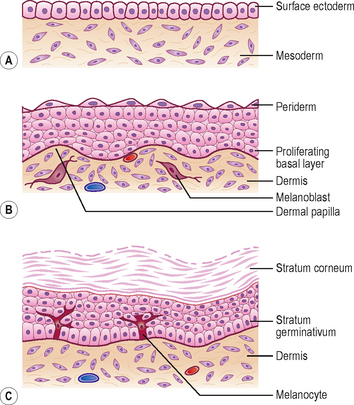

Hairs develop during the fetal period as proliferations of the stratum germinativum of the epidermis growing into the underlying dermis. The tip of the hair bud becomes a hair bulb and is soon invaginated by the mesenchymal hair papilla in which the vessels and nerve endings develop (Fig. 4.2A, B). The epidermal cells in the centre of the hair bud become keratinized to form the hair shaft, and the surrounding mesenchymal cells differentiate into the dermal root sheath (Fig. 4.2C). Small bundles of smooth muscle fibres called arrector pili muscles develop in the mesenchyme and are attached to the dermal sheath (Fig. 4.2C). Most sebaceous glands develop as buds from the side of the epithelial root sheath growing into the dermis; these glands produce an oily secretion that lubricates the hair and skin. The sweat glands develop as epidermal buds into the underlying dermis which become coiled to form the secretory part of the glands (Fig. 4.2C).

Mammary glands and teeth

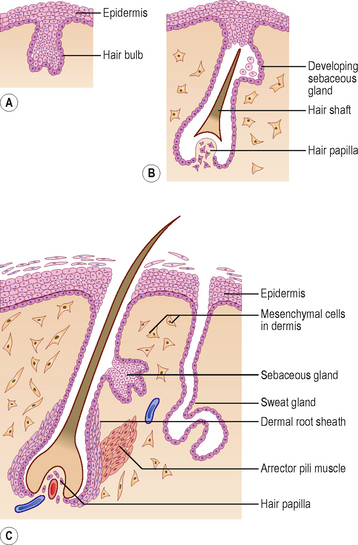

The mammary glands arise from a pair of epidermal thickenings called mammary ridges which appear in both sexes during the fourth week from the axilla to the inguinal region (Fig. 4.3A). Normally these ridges disappear except in the pectoral region where breasts develop, but part of the mammary ridges may persist to form an extra breast (polymastia) or supernumary breasts and nipples (Fig. 4.3A). The breast develops from a primary mammary bud which gives rise to several secondary buds that form the lactiferous ducts and their branches. The buds branch throughout the fetal period, become canalized and open into a small depression called the mammary pit of the nipple (Fig. 4.3B, C).

The teeth develop as tooth buds from the epithelial lining of the oral cavity along a U-shaped epidermal ridge called the dental lamina along the curves of the upper and lower jaws. The ectodermal tooth bud grows into the neural crest-derived mesenchyme, and passes through a ‘cap’ and a ‘bell’ stage. The enamel is produced by ameloblasts which are derived from the ectoderm; the underlying dentin and other tissues are derived from the mesenchyme and neural crest cells.

The musculoskeletal system

The mesenchyme gives rise to the musculoskeletal system. Most of the mesenchyme is derived from the mesodermal cells of the somites and the somatopleuric layer of lateral plate mesoderm (see Chapter 1). The mesenchyme in the head region comes from the neural crest cells. Regardless of their sources, a common feature of mesenchymal cells is their ability to migrate and differentiate into many different cell types, e.g. myocytes, fibroblasts, chondroblasts or osteoblasts. This differentiation often requires interaction with either epithelial cells or the components of the surrounding extracellular matrix.

The skeletal system

Development of the axial skeleton

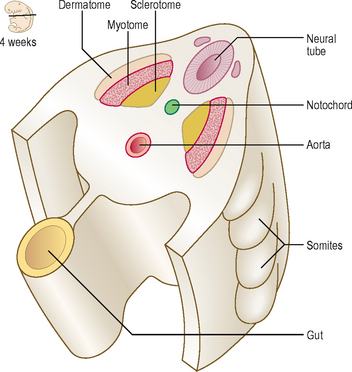

The axial skeleton is composed of the skull, vertebral column, sternum and ribs. This part of the skeleton is derived from the paraxial mesoderm, which is soon organized into the somites. The first somites appear on day 20 in the cranial region, and by 30 days approximately 37 pairs are formed. Somites appear as rounded elevations under the surface ectoderm on the dorsal aspect of the embryo from the base of the skull to the tail region. Each somite subdivides into two parts: the sclerotome and the dermomyotome (Fig. 4.4). The cells of the sclerotome give rise to the vertebrae and ribs, and those of the dermomyotome form muscle and the dermis of the skin.

The vertebral column

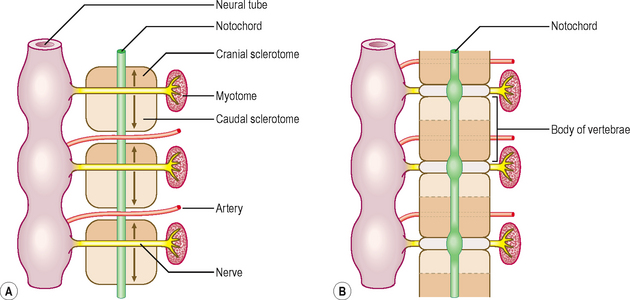

During the initial mesenchymal stage, the sclerotome cells migrate medially towards the notochord, and meet the sclerotome cells from the other side to form the centrum or vertebral body. Each sclerotome splits into a cranial and a caudal segment (Fig. 4.5A). The cranial half of the sclerotome consists of loosely arranged cells, whereas the caudal half contains densely packed cells. The caudal half of a sclerotome fuses with the cranial half of the sclerotome below to form the vertebral body (Fig. 4.5B). From the vertebral body, sclerotome cells move dorsally and surround the developing spinal cord to form the vertebral arch. In each vertebra, the costal and transverse processes develop from the vertebral arches. The vertebral arches of each vertebra join dorsally to form the spinous processes. The formation of the vertebral body is dependent on inducing substances produced by the notochord, and that of the vertebral arch, on the interaction of sclerotome cells with the surface ectoderm.

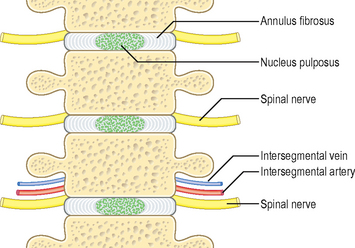

The intervertebral disc has an outer collagenous annulus fibrosus and a central gelatinous core, the nucleus pulposus (Fig. 4.6). The annulus fibrosus develops from the densely packed lower portion of the sclerotome, whereas the nucleus pulposus is derived from the notochord. The rest of the notochord at the level of the vertebral bodies soon disappears.

A spina bifida occulta (see Chapter 10 and Fig. 10.5A) may occur when the two halves of the vertebral arch fail to fuse behind the spinal cord. This minor anomaly usually occurs in the lumbosacral region, often marked by a patch of hairy skin overlying the affected area, and is often first identified on routine radiological examination.

Sternum and ribs

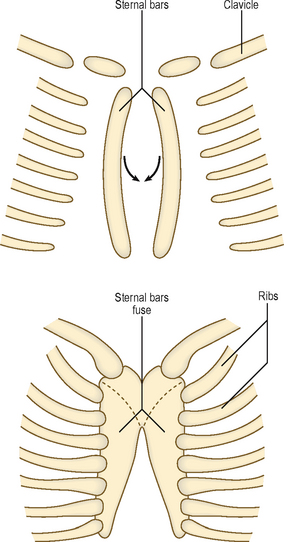

The sternum develops from a pair of cartilaginous bars that form in the ventral body wall. These bars fuse in the midline in a craniocaudal sequence to form the manubrium and the body of the sternum (Fig. 4.7). The anomaly of cleft sternum would occur if the two sternal bars fail to unite, and may present as a circular defect in the sternum, often an incidental finding at a radiological examination. The ribs arise from the costal processes of the vertebrae in the thoracic region. These become cartilaginous, grow laterally toward the sternum, and become ossified. At other vertebral levels the costal processes do not grow distally but are incorporated into the transverse processes of the vertebrae.

Skull

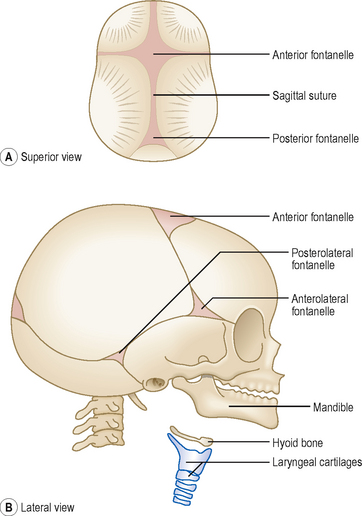

The bones of the cranial vault are thin at birth and are separated by fibrous tissue called sutures. The areas where more than two bones meet the unossified mesenchyme are known as fontanelles (Fig. 4.8). Six fontanelles are present at birth but the anterior and posterior fontanelles are most obvious. The growth of the brain is accompanied by expansion of skull bones, and both continue to grow during fetal life and early childhood. Not only do the sutures and fontanelles allow skull bones to expand but the fontanelles also override each other during birth to allow the fetal head to pass through the birth canal. Most of the fontanelles disappear during the first year because of growth of surrounding bones, but the anterior fontanelle remains membranous until 18 months after birth.

The skeleton of the viscerocranium is derived from the first two pharyngeal arches, which support the jaws (see Chapter 11). The mesenchyme in these arches condenses to form a rod of cartilage surrounded by perichondrium. Some of the perichondrium from the pharyngeal arches gives rise to ligaments attached to the skull, and most of the cartilage is replaced by membranous bone. The body and ramus of the mandible develops from the mesenchyme around the ventral end of the first pharyngeal arch cartilage (Meckel’s cartilage). The condyle and the chin area of the mandible ossify by the process of endochondral ossification. The ear ossicles, the hyoid bone and laryngeal cartilages are also derived from the cartilaginous bars of pharyngeal arches (see Chapter 11).

Development of the limbs and appendicular skeleton

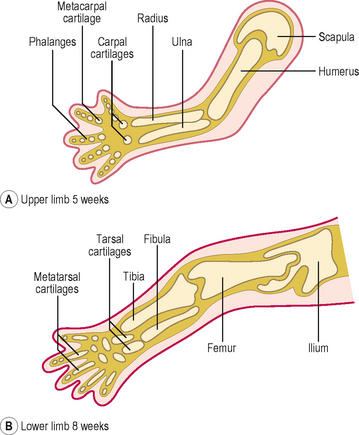

The appendicular skeleton consists of the limb girdles and the bones of the limbs. The bones of the appendicular skeleton develop from mesenchymal condensations which become cartilaginous models (Fig. 4.9). The clavicle is the only exception, which begins as a model membranous bone. The centres of ossification first appear in the limb bones during the eighth week. By the twelfth week, the shafts of the limb bones are ossified, though the carpal bones of the wrist remain cartilaginous until after birth. The ossification of the three largest tarsal bones of the ankle begins at about 16 weeks, but some of the smaller tarsal bones do not ossify until 3 years after birth.

The muscular system

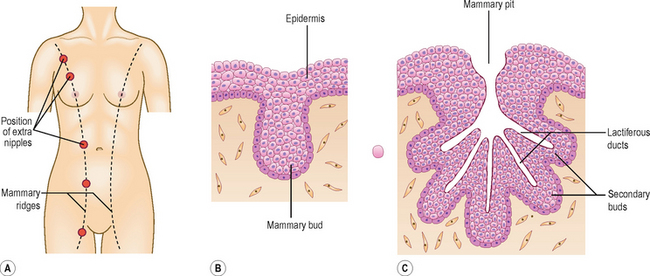

Skeletal muscles develop from the myoblasts derived from the somites, with the exception of much of the head musculature, which is derived from the pharyngeal arches or the neural crest mesenchyme (see Chapter 11). The muscles of the neck and trunk are derived from the myotomes, whereas the limb musculature develops from myogenic cells that migrate from the ventrolateral region of the dermomyotome of the somite.

Each myotome divides into a dorsal epimere and a ventral hypomere (Fig. 4.10). The epimere gives rise to the back muscles, including the erector spinae, whereas the hypomere forms the lateral and ventral muscles of the thorax and abdomen. The muscles derived from the hypomere include the intercostal muscles in the thorax, the three layers of the anterior abdominal wall, the rectus abdominis and the infrahyoid muscles. The spinal nerves divide into dorsal and ventral rami supplying each division of the myotome. The dorsal rami innervate the muscles derived from the epimeres, and the ventral rami innervate the muscles derived from the hypomeres.

Fig. 4.10 The origin of the muscular system from myotomes between 4 and 7 weeks showing its innervation.

The epidermis of the skin and its derivatives develop from the ectoderm. The dermis is from the lateral plate of mesoderm and dermatomes.

The epidermis of the skin and its derivatives develop from the ectoderm. The dermis is from the lateral plate of mesoderm and dermatomes. The musculoskeletal system is mesenchymal in origin, derived from somites, the lateral plate somatopleuric layer and the neural crest.

The musculoskeletal system is mesenchymal in origin, derived from somites, the lateral plate somatopleuric layer and the neural crest. The components of the axial skeleton are vertebrae, sternum and ribs. Individual vertebrae develop from sclerotome cells of two adjoining somites.

The components of the axial skeleton are vertebrae, sternum and ribs. Individual vertebrae develop from sclerotome cells of two adjoining somites. The developing skull has two parts: a neurocranium and a viscerocranium. The flat bones of the skull develop in membrane, but the base of the skull is derived from cartilaginous components.

The developing skull has two parts: a neurocranium and a viscerocranium. The flat bones of the skull develop in membrane, but the base of the skull is derived from cartilaginous components. The limb bones develop from endochondral ossification of cartilaginous precursors. The only exception is the clavicle which ossifies in membrane. The ossification of cartilaginous models of limb bones begins between the eighth and twelfth week.

The limb bones develop from endochondral ossification of cartilaginous precursors. The only exception is the clavicle which ossifies in membrane. The ossification of cartilaginous models of limb bones begins between the eighth and twelfth week. Limb anomalies are multifactorial and form as a result of genetic defects, drug actions and mechanical effects.

Limb anomalies are multifactorial and form as a result of genetic defects, drug actions and mechanical effects.

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box

Clinical box Clinical box

Clinical box