Chapter 5 The ill child – assessment and identification of primary survey positive children

Introduction

Sick children present particular challenges to the pre-hospital practitioner. The anatomy of children is different to that of adults, and this can result in differences in the presentation and severity of a range of conditions. Paediatric physiology also differs from that of adults, and although this means children often compensate very well for significant clinical illness it also carries the risk that a severe problem will be overlooked or underestimated. When compensatory mechanisms fail in children, they often do so rapidly, catastrophically and irreversibly. The index of suspicion of the pre-hospital practitioner must therefore be higher than for an adult when assessing the ill child, and the threshold for hospital admission will consequently be lower than for an adult patient with similar findings. The emphasis should be on detecting and treating the seriously ill child at an early stage to prevent deterioration rather than to attempting to cope with a decompensated, critically ill child.

The paediatric section of this text is divided into two chapters. The objectives of this first chapter are outlined in Box 5.1.

Whilst this chapter concentrates on identifying or ruling out potentially time critical problems, it should be remembered that many children have problems that are not immediately life threatening. Common illnesses affecting children are covered in Chapter 6.

Significant anatomical and physiological differences between children and adults

Airway

In infants (aged 0–1 years) and children (aged 1–8 years) the head is proportionately larger and the neck shorter than in adults. This can lead to neck flexion in the recumbent baby or child, precipitating airway obstruction. The trachea is also more malleable, and this coupled with the large tongue can result in airway obstruction if the head is over-extended when attempting to open the airway by positioning, particularly in infants. Milk teeth may be loose, and the smaller size of the mouth increases the risk of dislodgment or tissue damage. Compressing the surface of the skin below the lower jaw in an attempt to open the airway can result in the tongue being displaced and worsening obstruction. Infants less than 6 months old are obligate nasal breathers. The epiglottis is horseshoe shaped and the larynx higher and more anterior, the tracheal rings are soft and not fully formed, and the cricoid cartilage is the narrowest part of the upper airway. All have implications for airway management and the consequences of related illnesses.

Breathing

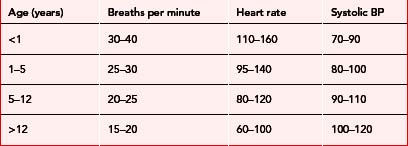

The total surface area of the lungs and the number of small airways is limited in infants and children and small diameters throughout the respiratory system increase the risk of obstruction. Infants have ribs that lie more horizontally and therefore rely predominantly on the diaphragm for breathing. They are more prone to muscle fatigue and therefore respiratory failure. Increased metabolic rate and oxygen consumption contribute to higher respiratory rates than in adults (Table 5.1).

Circulation

Infants and children have a relatively small stroke volume but a higher cardiac output than in adults, facilitated by higher heart rates (Table 5.1). Stroke volume increases with age as heart rate falls, but until the age of two the ability of the child to increase stroke volume is limited. Systemic vascular resistance is lower in infants and children, evidenced by lower systolic blood pressure (Table 5.1). The circulating volume to body weight ratio of children is higher than adults at 80–100 ml/kg (decreasing with age) but the total circulating volume is low. A comparatively small amount of fluid loss can therefore have significant clinical effects.

Range of normal development in children, and assessment strategies

Infants

The developmental milestones of infants are outlined in Table 5.2. Remember, there may be wide variation in the age of attaining these milestones.

| Age (months) | Activity |

|---|---|

| < 2 | Predominantly sleeping or eating |

| Unable to differentiate between strangers and carers/family | |

| 2–6 | Spends more time awake |

| Starting to make eye contact | |

| May follow movement of toys/lights with eyes | |

| May turn head towards sounds | |

| Starts to vocalise sounds | |

| Active extremity movements | |

| May recognise caregivers | |

| 7–12 | Sits unsupported |

| Reaches for objects and puts them in mouth | |

| Recognises caregivers and afraid of separation from them; afraid of strangers |

When assessing an infant, the caregiver can be asked to hold the child and get down to ‘baby level’. It is a good idea to say the child’s name, speak softly and avoid sudden movements. The examination may be commenced by simply observing the child, and then ‘hands on’ examination can begin starting with the least upsetting steps. It is wise to adjust the order of the examination according to the child’s behaviour – for example, listening to breath sounds and counting the respiratory rate when the child is calm and certainly before doing anything that may be painful or distressing. Your hands and any instruments should be warm, and clothing should be removed only one item at a time to maintain body warmth and reduce fear.

Children

The developmental milestones for children aged 1–12 are outlined in Table 5.3.

Table 5.3 Range of normal behaviours in children aged 1 to 12 years

| Age (years) | Activity |

|---|---|

| 1–2 | Initially crawling and walking supported by furniture, then walking and running Feed themselves Plays with toys Starting to communicate with increasing vocabulary; will understand more than they can vocalise Independent and opinionated: cannot be reasoned with Curious but with no sense of danger Frightened of strangers |

| 2–5 | Illogical thinkers (by adult standards) May misinterpret what is said to them Fearful of being left alone, loss of control, and being unwell Limited attention span |

| 5–12 | Talkative Understand the relationship between cause and effect Pleased to learn new skills Older children may understand simple explanations about how their bodies work and their illness Fearful about separation from parents, loss of control, pain and disability May be unable to express their thoughts Desire to ‘fit in’ with peers |

The child can be observed from a distance initially whilst the history is being taken, and then approached slowly, preferably avoiding physical contact until the child is familiar with you. Children should remain with caregivers, and sit on their lap if they wish to do so. Young children respond to praise – admiring clothes or a favourite toy and recognising good behaviour are effective ways to win them over. They may be soothed by being allowed to play with their own toys or by being allowed to hold instruments such as a stethoscope. The caregiver can assist with the assessment, by removing clothes or holding an oxygen mask. Use of very simple words and toys can facilitate explanations to the child. Critical parts of the assessment can be undertaken whenever the child is at their most calm: consider examining from toes to head. A limited element of control can be given to the child, asking which part the child would like you to examine first. Do not lie to children and, in particular, never tell them something will not hurt if it will!

Primary survey positive patients

Primary survey positive children fall into one of two groups. Those who are seriously ill but are currently compensating require immediate transportation to definitive care to prevent further deterioration. Pre-hospital treatment for this group of patients should be given en route: treatment that cannot be practically administered by a single practitioner in the back of a moving ambulance should be postponed until arrival at hospital, unless the patient decompensates prior to arrival. Those that are seriously ill but are no longer able to compensate will require some life-saving interventions ‘on-scene’ before transportation to hospital but this should be strictly limited to that which will allow delivery of a live child to the emergency department.

Recognition

The main features of the primary survey for children are described in Box 5.2.

Box 5.2 Main features of paediatric primary survey

Work of breathing

Decompensating primary survey positive patients

Table 5.4 describes the significant findings and pre-transportation treatment for children who are primary survey positive and decompensating. To minimise distress, parents should be encouraged to hold small children who remain alert.

Table 5.4 Recognition and pre-transportation treatment of the decompensating primary survey positive patient

| Problem | Findings | Pre-transportation treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory failure | Noisy upper airway becoming quiet without improvement in condition Very rapid and shallow or slow weak respirations Decreasing evidence of increased work of breathing due to exhaustion Significantly decreased air entry on auscultation Limited chest expansion Loss of wheeze without improvement in condition SpO2 less than 90% on high concentration oxygen Cyanosis Reduced AVPU score Flaccid or increased muscle tone No interaction with carers or responders Glazed, unfocused gaze Abnormal, weak or absent cry Hypoglycaemia |

Secure airway using the most simple manoeuvre if possible: use advanced interventions (e.g. intubation) only if simple manoeuvres fail Give high concentration oxygen via non-rebreathing mask Consider assisting ventilation with bag valve mask if respiratory rate is very fast or slow In the presence of wheeze consider nebulisation with beta-2 agonist and anti-cholinergic (e.g. salbutamol and ipratropium Consider nebulised epinephrine in the presence of suspected croup (1 ml of 1:1000 once only) Decompress tension pneumothorax Consider transmucosal glucose (Hypostop) or intravenous/intraosseous 10% dextrose 5 ml/kg |

| Circulatory failure | Increased respiratory rate in the absence of increased work of breathing Central pallor, mottling or cyanosis Cool skin centrally Bradycardia or falling heart rate in the absence of improvement in condition Central capillary refill time >5 seconds or absent Reduced AVPU score Flaccid muscle tone No interaction with carers or responders Glazed, unfocused gaze Weak or absent cry Non-blanching rash in an ill child |

Secure airway using simple manoeuvres if possible: use advanced interventions (e.g. intubation) only if simple manoeuvres fail Give high concentration oxygen via non-rebreathing mask Consider intravenous/intraosseous fluid challenge of 5 ml/kg (repeat up to 20 ml/kg) Consider intravenous/intraosseous 10% dextrose 5 ml/kg Consider benzylpenicillin IV or IM |

| Central nervous system failure | Reduced AVPU score Flaccid muscle tone No interaction with carers or responders Glazed, unfocused gaze Weak or absent cry Continuous fits, or failure to regain consciousness between fits Hypoglycaemia |

Consider the presence of undiagnosed respiratory or circulatory failure and treat accordingly. Otherwise: Secure airway using simple manoeuvres if possible: use advanced interventions (e.g. intubation) only if simple manoeuvres fail Give high concentration oxygen via non-rebreathing mask Consider assisting ventilation with bag valve mask if respiratory rate is very fast or slow Consider rectal diazepam (0–1 year 2.5 mg, 1–3 years 5 mg, 4–12 years 10 mg) or IV diazepam 250–400 μg/kg, but do not delay to obtain IV access Consider transmucosal glucose (Hypostop) or intravenous/intraosseous 10% dextrose 5 ml/kg |

Once life-saving interventions have been initiated, the child should be moved to the ambulance and transported immediately, continuing treatment en route as described in Table 5.5.

Table 5.5 Findings associated with compensating primary survey positive patients and en route treatment

| Problem | Findings | Treatment en route to hospital |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory distress | Noisy upper airway (snoring, stridor, muffled or hoarse speech) Grunting Increased respiratory rate Refuses to lie flat, or adopts tripod or sniffing position Use of accessory muscles (head bobbing in infants) Sternal, sub-sternal, supra-clavicular or intercostal recession present Nasal flaring Increased or asymmetrical chest expansion Wheezing SpO2 less than 94% on room air Pallor or peripheral cyanosis Normal AVPU score Good muscle tone; may be playing with toys Interacts with carers or responders Focused gaze Strong cry |

Secure airway using simple manoeuvres if possible: use advanced interventions (e.g. intubation) only if simple manoeuvres fail Give high concentration oxygen via non-rebreathing mask Consider nebulised budesonide in the presence of suspected croup (2 mg once only) or oral steroids (dexamethasone syrup 0.15 mg/kg) In the presence of wheeze consider nebulisation with beta-2 agonist and anti-cholinergic (e.g. salbutamol and ipratropium) |

| Compensated shock | Increased respiratory rate in the absence of increased work of breathing Peripheral pallor, mottling or cyanosis Cool skin peripherally, warm centrally Prolonged capillary refill >2 seconds centrally Increased heart rate Normal AVPU score Good muscle tone; may be playing with toys Interacts with carers or responders Focused gaze Strong cry |

Secure airway using simple manoeuvres if appropriate: use advanced interventions (e.g. intubation) only if simple manoeuvres fail Give high concentration oxygen via non-rebreathing mask Consider intravenous fluids 20 ml/kg (unless uncontrolled bleeding in which case use 5 ml/kg aliquots) |

Remember to pre-alert the receiving hospital of your estimated time of arrival and the child’s age and condition

Compensating primary survey positive children

Seriously ill but compensating children will have signs of either shock or respiratory distress but will have a relatively normal appearance and level of consciousness. Transportation to hospital should be commenced immediately for such patients and whatever appropriate treatment from Table 5.4 that is practical to initiate in a moving ambulance provided en route. Parents should be encouraged to hold small children to minimise distress.

The findings associated with compensating primary survey positive patients and recommendations for en route treatment are described in Table 5.5.

Primary survey negative children with need for early hospital attendance

Primary survey negative patients with the findings listed in Box 5.3 usually require hospital assessment and may need admission.

Box 5.3 Diagnostic criteria for primary survey negative patients requiring hospital admission

Some conditions suggesting need for early hospital review in primary survey negative patients:

Parents may have requested the assistance of healthcare providers after using the Baby Check scoring system.1 This uses a simple 19-point check list to help parents assess the severity of illness in babies up to 6 months old, and to determine the need for medical assessment.

Consent to treatment

Young person over the age of 16

Young people over the age of 16 should normally be treated as competent adults. Informed consent to treatment should be sought from the patient. Adults with parental responsibility may not refuse treatment on behalf of the minor if the young person has consented to it. Adults with parental responsibility may, however, over-ride the decision of a minor to refuse life-saving treatment, as may a court of law. If both a young person and those with parental responsibility refuse life-saving treatment this can be over-ridden by a court of law or, in an emergency, health professionals. ‘Parental responsibility’ is defined in Box 5.4.

Child or young person under the age of 16 who is not ‘Gillick aware’

If possible, obtain informed consent to treatment from an adult with parental responsibility (see Box 5.4) as well as the child. If such an adult is not immediately available and treatment cannot be delayed, the legal doctrine of necessity may be invoked if the treatment is necessary to save life, ensure improvement, or prevent deterioration in health. The doctrine of necessity can only apply if the treatment provided is in accordance with normal current medical practice and is restricted to that required until parental consent can be obtained.

If those with parental responsibility refuse treatment, a court order should be sought. If this is not feasible because treatment is life-saving and cannot be delayed, the practitioner should discuss the need for the treatment in detail and document this in the presence of a witness. If possible, a colleague should provide a supporting written recommendation that the treatment is necessary and appropriate, and a defence union contacted.

Child protection

Taking action

All healthcare professionals have a duty of care to report any child that might be at risk from abuse to the appropriate authorities and should be familiar with their organisation’s procedures for child welfare and protection. However, in the event that child abuse is suspected, it is not the role of healthcare workers to undertake an investigation. In particular, children should not be asked leading questions as this may prejudice any future criminal enquiry. Concerns should be referred to Social Services without delay or, in the event that immediate action is required, to the police. Child protection policies should document how to make contact with the appropriate organisations outside of normal working hours. Verbal notifications must be followed-up with a written report, and all findings and concerns should be documented in the patient record in detail. It is a good idea to ensure that a referral not requiring immediate action is acknowledged in writing: if it is not, this should be followed up with the relevant agency.

4th edn. Advanced Life Support Group, editor. Advanced paediatric life support. The practical approach. BMJ Books, London, 2002.

2nd edn. Advanced Life Support Group, editor. Pre-hospital paediatric life support. The practical approach. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2005.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatric education for prehospital professionals. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett, 2000.

Department of Health. What to do if you are worried a child is being abused (summary). London: Crown Publishing, 2003.

Montague A. Legal problems in emergency medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Morley CJ, Thornton AJ, Cole TJ, Hewson PH, Fowler MA. Baby Check. Available online http://nicutools.org/ (5 Mar 2007)