5 THE HIP

Applied Anatomy

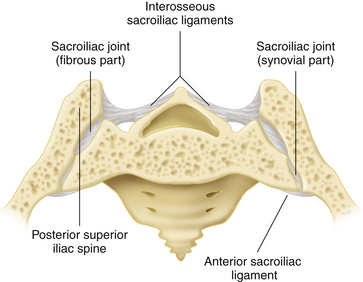

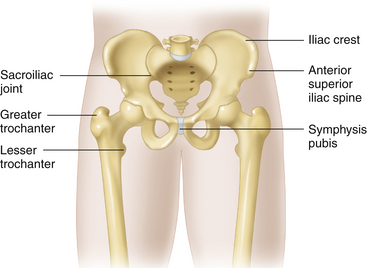

The morphology of the sacroiliac (SI) joint varies considerably with age, among individuals, and even from side to side in the same individual. It represents the largest paraxial joint, with a surface area of more than 17 cm2 in adults. The anteroinferior ventral part of the SI joint is synovial, whereas the posterosuperior part is a fibrous joint supported by powerful ligaments. The joint is surrounded by a thin capsule that may be absent posteriorly. Little movement occurs at the SI joint (Figure 5-1; see also Figure 8-6 in Chapter 8). The SI joint is innervated by the L5 and S1 through S4 nerve roots.

HIP JOINT

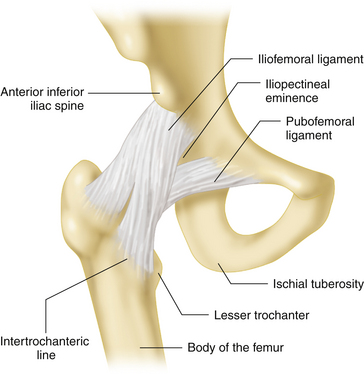

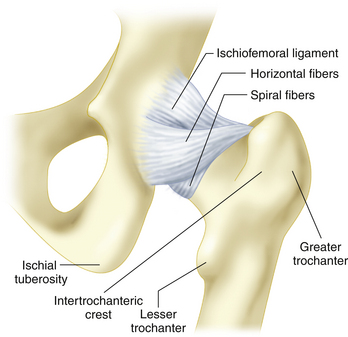

The anterior capsule is reinforced by the powerful Y-shaped iliofemoral ligament, which prevents excessive hip extension and external rotation (Figure 5-2). The weaker posterior capsule is reinforced by the thinner ischiofemoral ligament, which prevents excessive external rotation, and the pubofemoral ligament, which opposes excessive hip abduction (see Figure 5-2). The ligamentum femoris teres—which is a channel for blood vessels to the femoral head, is located between the pit of the femoral head and the transverse ligament of the acetabulum. It provides little stability but nourishes a small area of the femoral head adjacent to the attachment of the ligament. Therefore, dislocation of the femoral head from the acetabulum is resisted primarily by the acetabular labrum and by the strong hip joint capsule, which incorporates the capsular Y ligament (see Figure 5-2). The fibers of the hip joint capsule are wound around the femoral neck so as to tighten with hip extension and internal rotation (Figure 5-3). The position is uncomfortable for patients with hip arthritis because of tension on the capsular structures. The intracapsular space of the hip joint is smallest with the hip in extension and internal rotation, a position that produces maximum tension on the capsular Y ligament. Consequently, patients with inflammation of the hip joint often hold the extremity flexed and externally rotated as a position of relative comfort.

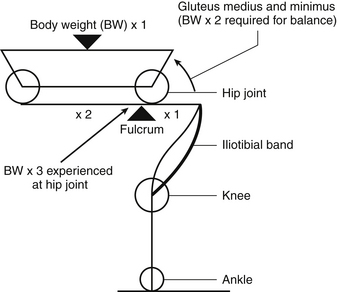

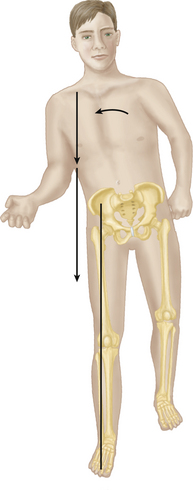

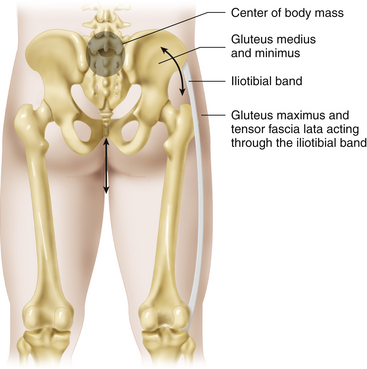

Having the femoral head situated in an offset position on the femoral shaft, through the femoral neck, minimizes bony impingement and maximizes normal hip ROM. It does, however, require strong muscular support to stabilize the trunk over the hip joints, especially in single-leg stance phase, when the body’s center of gravity is medial to the supporting leg. One can consider the hip joint as a fulcrum for a lever, with the body’s center of gravity acting approximately 1 cm anterior to the first sacral segment in the midline (Figure 5-4). To counteract this load, the gluteus medius and minimus act in conjunction with the tensor fascia lata and gluteus maximus muscles, which function mainly through their insertion into the iliotibial band. Given the fact that the distance is twice as far to the center of gravity as it is to the gluteus insertion into the proximal femur, a force approximately equal to three times body weight is transmitted through the hip joint during single-leg stance, compared with one half of the body weight during normal bilateral stance (Figure 5-5).

FIGURE 5-4 HIP BIOMECHANICS DURING SINGLE-LEG STANCE.

(From Gross J, Fetto J, Rosen E., eds.: Musculoskeletal Examination, 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2002.)

Hip Pain and History Taking

Patients who complain of hip pain often mean very different things, from pain in the lower back or buttock region to groin pain or thigh pain. Patients with true hip joint disease will classically complain of pain in the groin region, although this varies depending on the type of hip pathology. Pain typically radiates down toward the anterior aspect of the knee. Individuals who are experiencing pain on the lateral aspect of the hip, in the region of the greater trochanter, or pain in the lower back or in the buttock area may also complain of hip pain. To determine what the patient’s complaint of “hip pain” really means, it is essential to ask the patient to describe exactly where the pain is primarily located and where it radiates. Other than pain, the patient may complain of limited function, stiffness, limping, and audible or palpable clicking or snapping noises about the hip. As with any history, it is important to delineate the onset of these symptoms, their severity, whether they were preceded by injury or overuse, and whether there are any constitutional or systemic symptoms. Inflammatory arthritis generally affects multiple joints, and although the hip may be the presenting problem, it is important to inquire about similar symptoms in any other joints. It is essential to inquire about childhood hip problems, previous injuries, and the nature of any previous hip or spinal operations.

Common Painful Disorders of the Hip Region

TROCHANTERIC BURSITIS

This condition is extremely common. The greater trochanteric bursa may become inflamed due to direct trauma or overuse with strenuous physical activity, such as running or jumping. A tight iliotibial tract, with a positive Ober test, may be present. The inflamed bursa becomes painful with activities that compress it between the greater trochanter and the overlying iliotibial band. Patients may be unable to lie on the affected side, and they usually experience pain with weight bearing, especially in a single-leg stance, as the iliotibial band tightens to maintain the body’s upright posture. Tenderness over the greater trochanter with direct palpation and pain with resisted hip abduction are typical physical findings. A fluid-distended bursa associated with a palpable fluctuant swelling may be palpated on rare occasions in a thin patient.

CONSIDERATIONS IN PATIENTS AFTER TOTAL HIP REPLACEMENT

Safety Considerations

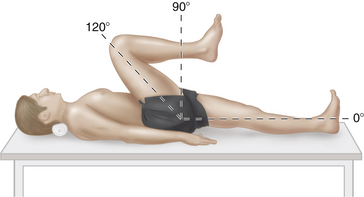

Special care should be taken when evaluating the hip joint of a patient who has previously undergone total hip replacement. In the early postoperative period, the clinician should ask patients whether their surgeon has informed them of any specific restrictions. For example, hip revision surgery may involve compromise to the hip abductor muscles, and active hip abduction may be contraindicated in the early postoperative period. Similarly, patients may be instructed to avoid weight bearing during the initial 6 weeks after complex revision hip reconstructive surgery and occasionally after uncemented or complicated primary hip replacement surgery. Hip precautions in the early postoperative period are meant to minimize the risk of hip dislocation, although with the newer surgical techniques, these restrictions are being relaxed. The restrictions involve limiting hip flexion beyond 90°, internal rotation of the hip in flexion, external rotation of the hip in extension, and hip adduction beyond the midline. When testing ROM, the risk of anterior dislocation of the hip is greatest with the hip in extension, adduction, and external rotation. The risk of posterior dislocation is greatest when the hip is flexed, internally rotated, and adducted.

Pain after Total Hip Arthroplasty

TENDINITIS AND CONTRACTURES OF TENDONS AND MUSCLES

Before hip replacement surgery, contractures may have formed in the soft tissues around the hip as a consequence of arthritis-related joint stiffness. These muscles and tendons may become painful as a consequence of increased ROM and tension on the structures after successful joint replacement surgery that allows greater ROM. The hip abductors and flexors are most commonly affected. The patient may complain of a deep anteromedial or medial pain that is worse with active hip flexion or active adduction. Tenderness should be evaluated over specific tendons, although the iliopsoas tendon usually cannot be palpated because of its deep insertion. Pain with active contraction of the affected tendon–muscle unit and pain with passive stretch are consistent with the diagnosis of tendinitis.

Physical Examination

INSPECTION

It is often easiest to divide the inspection portion of the exam into that which can be done with the patient standing and then that which should be done with the patient supine. With the patient standing, the examiner should inspect the patient’s gait (see Gait Analysis). The examiner should then examine the standing patient from the front, from each side, and from the back. In this position it is easier to detect the presence of spinal curvature and pelvic tilts. These are assessed by examining the relationship between the adjacent spinous processes and the left and right iliac crests. A leg-length deformity may be apparent while the patient is standing with the feet together. If the patient needs to flex one knee to keep the pelvis level, the side with the flexed knee might be long. Conversely, if the pelvis is tilted to one side and the knees are fully extended, the side on which the pelvis is lower may be short. Gross varus or valgus deformity of the knee can also be evaluated (see Chapter 6). When the patient moves to a supine position, a more detailed inspection of skin, superficial, and deep tissues can be performed.

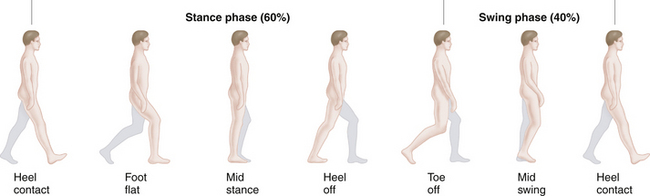

GAIT ANALYSIS

Normal gait involves a complex integration of muscle and joint activity that results in forward propulsion of the body with minimum displacement in the vertical and horizontal planes. Each leg alternates between a stance phase and a swing phase (Figure 5-6). During normal gait, the stance phase accounts for approximately 60% of the gait cycle. With faster walking speed, stance time is reduced and swing time is increased. The stance phase includes heel strike, foot flat, midstance, heel lift, and toe lift. Swing phase begins after toe lift and involves an initial period of acceleration, followed by midswing and a period of deceleration before heel contact and the stance phase begin again.

Vertical displacement of the body’s center of gravity is minimized by the following mechanisms: 1) a slight pelvic drop during midswing, after an initial rise of the pelvis on the unsupported side after toe lift; 2) pelvic rotation forward on the swing side; 3) ankle plantar flexion shortly after heel strike; 4) stance phase knee flexion; and 5) ankle plantar flexion in preparation for toe lift. The body’s center of gravity moves laterally by a distance equal to the space between the ankle joints. If the axis of the femur and tibia were collinear, then the lateral displacement would equal the distance between the hips. However, physiological genu valgus acts to minimize lateral displacement of the center of gravity during gait.

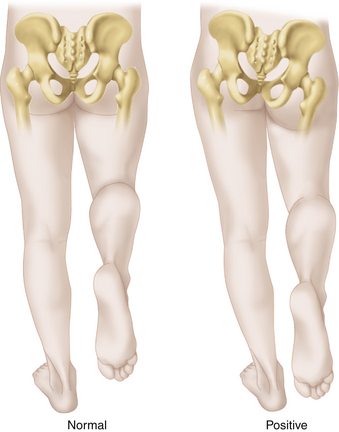

Trendelenburg Sign and Gait

In 1895, Friedrich Trendelenburg described a clinical sign present in patients with weak hip abductors due to poliomyelitis or congenital hip dislocation. The Trendelenburg sign is observed by having the standing patient alternately raise each leg for at least 30 seconds. The examiner stands behind the patient and observes the pelvis. Normally, the pelvis rises up on the unsupported side due to contraction of the gluteus medius to maintain body balance, but the trunk should not swing over the stance leg by more than a few degrees. In a positive uncompensated Trendelenburg sign, the pelvis drops down toward the unsupported side. This indicates weakness of the abductor muscles of the planted leg (Figure 5-7). The dropping pelvis will be observed only if the patient is prevented from compensating for the weak abductor muscles by thrusting the body over the planted leg. If the patient must thrust the weight over the leg in stance phase when lifting the opposite leg, this is considered a positive compensated Trendelenburg sign (Figure 5-8). Normally, a patient should be able to maintain the muscle force for at least 30 seconds. If the sign is initially negative (normal) but becomes positive within 30 seconds, this is known as a delayed (compensated or uncompensated) Trendelenburg sign and suggests muscle weakness or progressive pain inhibition of muscle contraction.

Gluteus Maximus Gait

An individual with hip extensor weakness tends to thrust the pelvis forward while leaning back with the trunk and shoulders at heel strike. This passively extends the hip until the iliofemoral ligament becomes taut and stabilizes the lower extremity (see Figures 5-2 and 5-3). The center of gravity can then move forward over the planted leg without it collapsing.

Drop-Foot Gait

Nerve injury to the peroneal division of the sciatic nerve results in weakness of the foot and ankle dorsiflexor muscles. With severe weakness of ankle dorsiflexion, the toes drag on the floor during swing phase, unless the patient lifts the foot higher than normal by exaggerated flexion of the hip and knee (high-steppage gait). The patient may also clear the ground by circumducting the leg out to the side during swing (circumduction gait). During heel strike, a weak tibialis anterior muscle cannot hold the foot, which slaps to the ground shortly after heel strike (slap-foot gait).

PALPATION, LANDMARKS, AND SPECIFIC MANEUVERS

Is There Pathology of the Soft Tissues, Muscles, or Tendons?

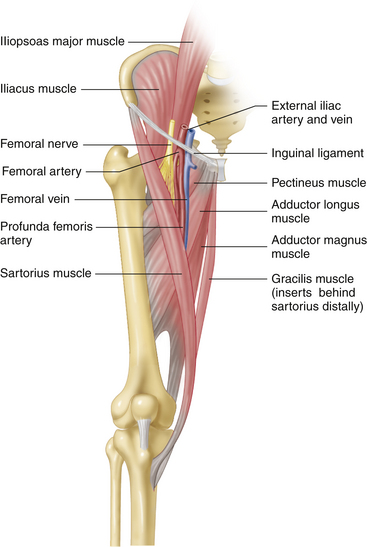

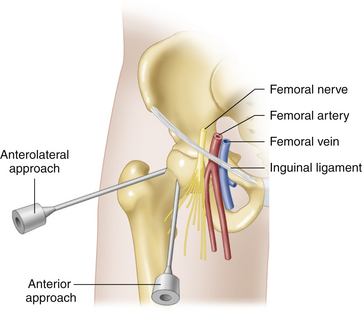

Femoral neurovascular structures. The vascular status of both limbs should always be determined as part of a lower-extremity evaluation. A quick arterial screening test involves examining the quality of the distal skin and palpating the pedal pulses (dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial). If distal arterial circulation is intact, there is usually no proximal impediment to arterial flow, and a detailed examination of femoral and popliteal pulses may not be required. The femoral artery can be palpated just lateral to the midpoint of the inguinal ligament. The femoral vein lies immediately medial to the artery but usually cannot be palpated. The femoral nerve lies lateral to the artery, within the iliopsoas muscle sheath, and also cannot be palpated (Figure 5-9). Lymph nodes that drain the leg are located medial to the vein. Some nodes are normally palpable, but enlarged, painful nodes may indicate infection or other pathology.

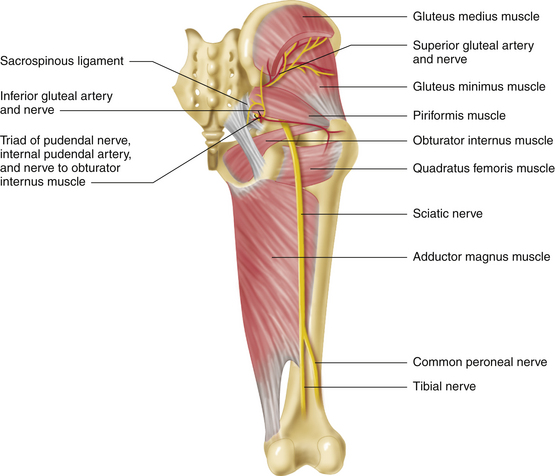

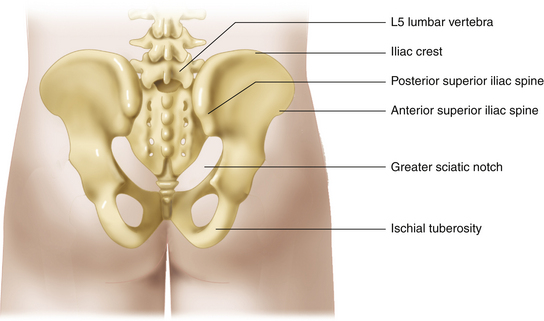

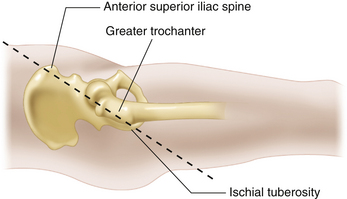

Sciatic nerve and adjacent structures. With the patient in the lateral position, and the hip slightly flexed, the sciatic nerve may occasionally be palpable in thin individuals, just superior to a line connecting the ischial tuberosity and the greater trochanter, where the nerve lies on the obturator internus tendon and the quadratus femoris muscle. Tenderness in this area and just above it, in the greater sciatic notch region, may indicate sciatic nerve irritation or piriformis muscle spasm or inflammation. The piriformis muscle lies somewhat higher, above the line between the greater trochanter and the ischial tuberosity, but it usually cannot be palpated. The sciatic nerve typically exits through the greater sciatic notch just below the piriformis muscle, but it may penetrate the muscle or exit entirely above it (Figure 5-10).

Active muscle contraction is painful in the face of an inflamed musculotendinous unit. The iliopsoas can be isolated to some degree with the patient seated at 90° and the hip slightly externally rotated. The patient is then asked to flex the hip against resistance with the knee flexed or extended. Pain in the groin region may be due to inflammation along the iliopsoas or at its insertion into the lesser trochanter.

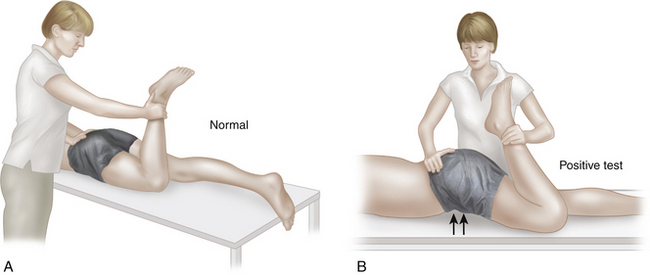

Piriformis muscle pathology. Piriformis syndrome is caused by piriformis muscle sprain or inflammation or by irritation or compression of the sciatic nerve as it passes the piriformis muscle posterior to the hip joint. A history of blunt, local trauma is common. Piriformis syndrome is associated with posterior hip pain produced by resisted external rotation of the hip with the hip and knee flexed at 90° (Pace test). Buttock pain—exacerbated by passive hip Flexion, Adduction, and Internal Rotation (FAIR test)—is also commonly present. In the piriformis test, the piriformis muscle is isolated by flexing the hip to approximately 60°, with comfortable knee flexion, in either the supine position or a lateral decubitus position. The examiner then passively stretches the piriformis muscle by bringing the knee into adduction (Figure 5-11). Active abduction of the limb against resistance can also be tested. Pain results if the muscle or tendon is strained, and radicular pain may indicate sciatic nerve irritation at the level of the piriformis muscle.

A number of tests have been developed to evaluate specific conditions. These are applied as required based on the history of potential pathology.

Is the Iliotibial Band Tight?

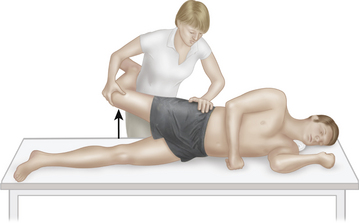

With the patient in the lateral position, the uppermost hip being evaluated is abducted and extended, and the knee is flexed. On removal of the medial support, the normal hip passively adducts to allow contact of the knee with the examining table (Ober test). A tight iliotibial band prevents the hip from adducting passively (Figure 5-12). In complete deformity due to severe contraction of the iliotibial band, the hip is held flexed, abducted, and externally rotated; the knee is flexed with a genu valgus deformity; and pes equinovarus, unequal leg lengths, and compensatory lumbar lordosis are often present.

Are the Hamstring Muscles Tight?

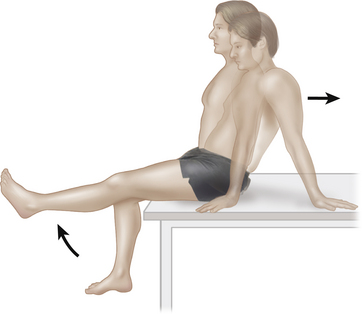

The hamstring muscles cross both the hip and the knee joints. Hamstring muscle tension can be properly assessed only if hip flexion is normal, the hamstring muscles are relaxed (by flexing the knee), and there is no evidence of sciatic nerve root irritation. While the patient is sitting with hips and knees in 90° flexion, the knee is extended on the side being tested. If the hamstrings are tight on that side, the patient will lean back to extend the hip and avoid tension in the tight hamstring (tripod sign or flipping sign). To balance themselves on the examining table as they lean back, patients may place their arms behind them, creating a tripod to support the trunk (Figure 5-13).

Is the Rectus Femoris Muscle Tight?

The rectus femoris muscle crosses both the hip and the knee joint. Muscle contracture can be demonstrated by noting movement at one joint as the muscle is stretched at the other. In the Ely test, the patient lies prone as the affected knee is flexed; a tight rectus muscle will cause the hip joint to flex, resulting in elevation of the affected buttock (Figure 5-14). Conversely, if the patient is supine, and the knee is flexed over the end of the examining table, the affected knee will extend as the hip joint is extended. (Hip extension is accomplished by flexing the opposite hip passively to flatten the lumbar lordosis, as in the Thomas test, and then pushing the affected hip into extension.)

Is There Pathology Involving Bony Structures?

Greater trochanters. The greater trochanters are readily palpated in most individuals, in supine or standing position, by placing the extended fingers of both hands on the lateral aspect of each upper thigh and feeling gently from the buttock posteriorly to the thigh anteriorly, until the firm bony prominence of the greater trochanter is detected. The superior and posterior aspect of the greater trochanter is usually the most readily palpable, and the superolateral area is generally the point of tenderness in trochanteric bursitis (Figure 5-15). Trochanteric bursitis is a common cause of hip pain, and palpation for tenderness in this area is usually part of a routine hip examination.

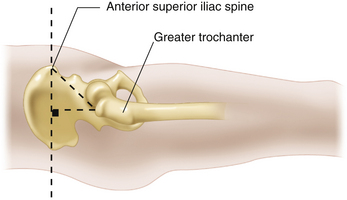

Iliac crests and anterior and posterior superior iliac spines. The iliac crest can be readily palpated in most individuals. The relative position of the two iliac crests in relation to the spine and the lower extremities is used to evaluate joint deformity and ROM. The most medial and distal point of the iliac crest is the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). This landmark is used as a reference point when measuring leg lengths, when assessing pelvic position in the measurement of hip ROM, and when evaluating pelvic obliquity. From behind, in the prone or standing patient, the PSIS can be palpated by following the iliac crest downward and posterior, until the most distal and medial point is reached (Figure 5-16). This landmark is used to further delineate the spatial orientation of the pelvis. It is also useful during surgery as a landmark for posterior approaches to the hip and acetabulum. Palpation upward from the midline at the level of the posterior superior iliac spines reveals the S1 spinous process and, above it, the more prominent L5 spinous process.

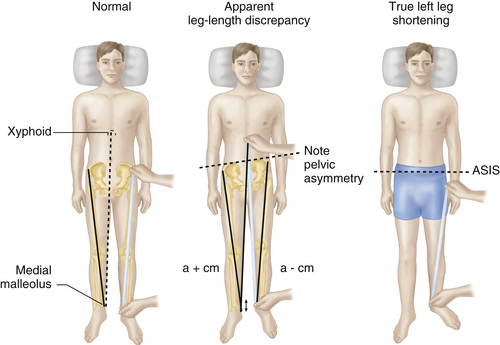

MEASURING LEG LENGTH

An apparent or functional leg-length discrepancy may be quantified by measuring from the xiphoid cartilage or umbilicus to the distal end of the medial malleolus of each ankle. Apparent leg-length discrepancy may be caused by pelvic obliquity or deformity, asymmetric hip or knee fixed flexion deformity, or a true difference in the lengths of the lower extremities (Figure 5-17). Measuring from a bony pelvic landmark, such as the ASIS, to the medial malleolus negates the effect of pelvic obliquity (see Figure 5-17) but may still be an inaccurate comparison of leg lengths if there is asymmetric fixed deformity in one hip or knee joint. Therefore, measurement of true limb lengths requires that any deformity on one side be replicated on the other before measuring. Sliding the tape up to the ASIS from below allows for easy identification of the landmark, even in a relatively heavy individual, and the distal end of the medial malleolus is readily identifiable.

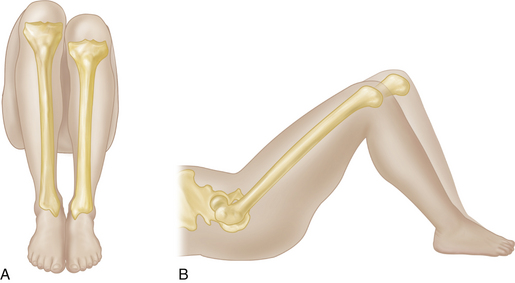

True leg-length discrepancy may be caused by proximal displacement of the femur (collapse of the femoral head, hip dislocation) or by shortening of the lower-extremity long bones. A difference of less than 1.0 to 1.5 cm between the two legs can be normal and does not produce any significant functional problem. Shortening from the ASIS to the greater trochanter often indicates coxa vara, whereas shortening from the greater trochanter to the lateral knee joint line suggests shortening of the femoral shaft. Shortening of the tibial shaft is associated with shortening of the distance between the knee medial joint line and the medial malleolus. The length of the femur and tibia can be compared by direct measurement to the medial joint line of the knee or the medial femoral condyle, but direct observation with the hips and knees flexed and the heels placed a similar distance from the hips will uncover asymmetry below or above the knee joint, as manifested by the relative positions of the superior and anterior aspects of the knees (Figure 5-18).

FIGURE 5-18 LEG-LENGTH DISCREPANCY.

A, The tibia on the patient’s left is shorter. B, The femur on the right is shorter.

HIP RANGE OF MOTION

Hip ROM should be assessed actively and passively, paying particular attention to the location of any discomfort felt during mobility testing. In reality, passive testing is performed immediately after the patient has reached maximum active movement in the given direction, to maximize efficient flow of the examination. Normal ROM varies considerably but should not be painful. It is essential to compare the two sides, usually examining the more painful extremity last. After active and passive ROM have been assessed, the muscle strength of the movement is graded on a six-point scale, with values of 0, or no activity; 1, a flicker; 2, movement with gravity eliminated; 3, movement against gravity; 4, movement against resistance; and 5, normal muscle power.

Hip Flexion

After the active flexion has been recorded, passive ROM should be tested. The patient should start by lying supine with the knee flexed, and the hip is flexed passively until a firm end point is reached (Figure 5-21). This may not occur until the knee touches the chest (about 120°), but other normal individuals may demonstrate only 100° of flexion. Even patients with a solid hip fusion may appear to have some hip flexion mobility due to pelvic rotation. To eliminate the possibility of misinterpreting pelvic rotation as hip flexion, the examiner should place a hand behind the upper pelvis and lower lumbar spine to monitor pelvic rotation. Once that firm end point has been palpated, the examiner should add a little extra stress in the direction being tested to test for stress pain that may be indicative of an actively inflamed joint.

Hip flexion power can be assessed with the patient supine or in a sitting position, beginning with the hip in approximately 90° of flexion. Although the rectus femoris also crosses the hip and knee joint, the iliopsoas muscle (L2, L3) is the main hip flexor. Because it inserts posteriorly into the lesser tuberosity of the femur, the iliopsoas can be isolated by externally rotating the hip during flexion strength testing.

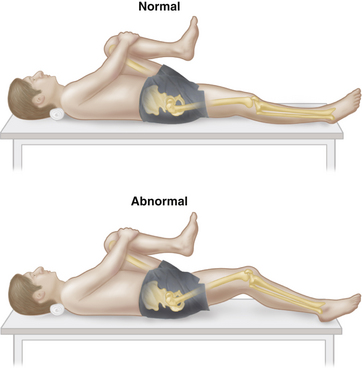

Hip Extension

Thomas test for fixed flexion deformity. When assessing hip ROM, it is essential to rule out a fixed flexion deformity. Such a deformity, which is common with hip joint arthritis, may be masked in the supine position due to an exaggerated lumbar lordosis that allows the legs to lie flat on the examining table. To assess for fixed hip-flexion deformity, the lumbar lordosis must be flattened completely by rotating the pelvis back, but care should be taken to avoid overrotating the pelvis and thereby overestimating the amount of deformity. The easiest way to rotate the pelvis is to use the opposite leg as a fulcrum. By passively bringing the opposite flexed hip and knee up toward the patient’s chest, while feeling for flattening of the lumbar lordosis with the other hand behind the lower back, the correct pelvic position can readily be achieved. The patient may be asked to hold the flexed hip in this position with the hands placed around the knee to “hug” it toward the chest. Sometimes it is easier to flex both hips and knees until the lordosis is flattened. The hip to be tested is then extended until an end point is reached. If the femur can be dropped completely down to the examining table, no fixed flexion deformity of the hip is present, although extension may still be limited compared with the other side. The angle between the examining table and the femur of the limb being tested represents the degree of fixed flexion deformity in that hip joint (Figure 5-22). This maneuver was first described by Hugh Owen Thomas in the late 1870s and has become known as the Thomas test. It should be noted that a flexion deformity of the knee may masquerade as a fixed hip-flexion deformity, because it prevents the femur from lying flat on the table. In this circumstance, one can drop the lower leg of the side being tested off the side of the examining table. The angle between the table and the femur will then represent the magnitude of any fixed hip-flexion deformity. A fixed flexion deformity of the hip may be caused by capsular or muscle contracture or by joint deformity.

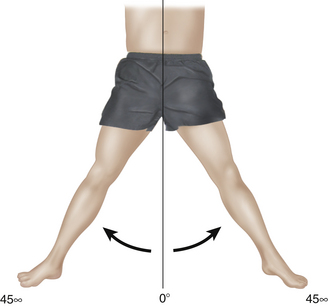

Abduction

Active and passive hip abduction can be measured in both flexion and extension. With the patient lying supine, the pelvis is stabilized by placing the examiner’s hand on the opposite ASIS. The patient is instructed to abduct one leg at a time. Maximum abduction occurs at the point just before the ASIS begins to move, with any further movement representing pelvic tilt as opposed to hip joint motion (Figure 5-23). The same movement is then performed passively. Similarly, with the hip and knee in 90° of flexion, the knee is moved laterally toward the examining table. Again, lifting off of the opposite hemipelvis indicates the beginning of pelvic motion and the limit of hip joint abduction. Assessing abduction of both limbs simultaneously obviates the problem of having to stabilize the pelvis and can also reveal subtle differences between the two sides more readily than individual limb testing can. Normal hip abduction is about 45° in extension and 60° in flexion, although there is considerable interindividual variation. The gluteus medius (L5; also L4 and S1), along with the gluteus maximus (S1, S2) and the tensor fascia lata, which insert into the iliotibial band, represent the main hip abductors. Hip abduction power is most easily tested in the opposite lateral decubitus position. In this position the pelvis is stabilized on the examining table by the body. The examiner can then resist hip abduction either in full extension or in varying degrees of hip flexion.

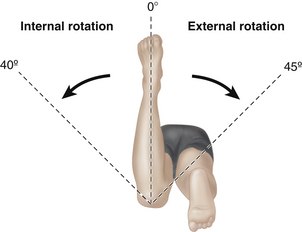

Internal and External Rotation

Rotation can be assessed in either the prone position (Figure 5-24) or supine position, and it can be evaluated with either the hip in flexion or in extension. Active and passive internal and external rotation are generally performed as part of the same movement. With the patient in the supine position and the knee flexed to 90°, the patient is asked to rotate the raised foot down toward the resting foot while keeping the thigh flexed at 90°. This will test external rotation. Rotating the foot in the other direction will test internal rotation. This same movement is then performed passively. The examiner should make note of the relative position of each hemipelvis to detect pelvic rotation that could result in overestimation during rotation testing; however, it usually is not necessary to stabilize the pelvis manually. The main external rotators of the hip are the piriformis, obturator externus, obturator internus, gemelli, and quadratus femoris muscles (L4, L5, S1). The iliopsoas and pectineus muscles are also weak external rotators. The normal range of external rotation is about 45°. Internal hip rotation is less powerful than external rotation. The normal range is about 40°. The gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fascia lata are the main internal rotators (L4, L5, S1), with assistance from the semitendinosus and semimembranosus. Alternatives to testing this range-of-motion test rotation in hip extension, which can be accurately quantified with the patient prone. In the prone position, with the knees flexed to 90°, the angle between the tibia and an imaginary line perpendicular to the examining table can be used as a goniometer to measure internal and external hip rotation. It is important to remember that internal hip rotation involves rotation of the lower leg, rotating away from the midline, whereas external hip rotation involves rotation of the lower leg toward the midline. Rotation in hip extension with the patient supine, determined by rolling the leg medially and laterally, is less accurate and requires consideration of the transepicondylar femoral axis and the patella. Relying on the foot to demonstrate the amount of internal or external hip rotation can lead to errors.

Is the Sacroiliac Joint Painful?

There are many tests that attempt to stress the SI joints. The FABER test (Flexion, ABduction, and External Rotation) is also known as the Patrick test, but the ankle-to-knee or heel-to-knee test is the most common term for it. With the patient in the supine position, the affected hip is externally rotated with the knee flexed, so that the affected ankle can be placed on top of the opposite knee in a number-four position. Applying downward pressure to the affected knee stresses the hip joint and may cause typical hip pain. In the absence of hip pathology, when the pelvis is stabilized by applying pressure over the opposite iliac crest, the affected SI joint is stressed (Figure 5-25). Pain in the gluteal region of the stressed side is considered a positive test.

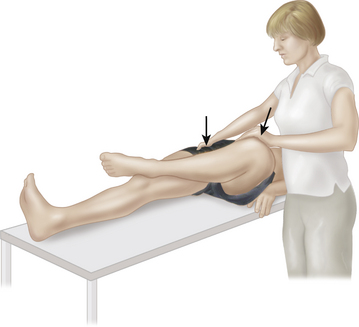

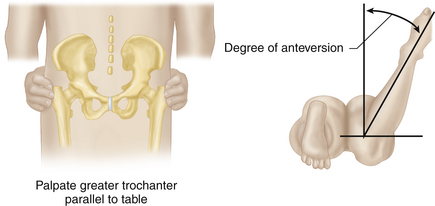

What Is the Degree of Femoral Anteversion?

Although a computed tomographic (CT) scan provides the most accurate method of measuring the degree of femoral anteversion, an approximation can be achieved by considering the position of the greater trochanter during hip rotation (Craig test). In a normal individual, the greater trochanter will be felt most prominently and directly lateral with 10° to 15° of internal hip joint rotation when the femoral neck is parallel to the floor. The degree of internal rotation required to bring the trochanter into this position can be noted in a prone patient with the knees flexed to 90°. The examiner places the greater trochanter into the most prominent position by rotating the hip. The angle between the leg and an imaginary line perpendicular to the floor from the knee denotes the degree of rotation required to achieve this position, which corresponds to the degree of femoral anteversion (Figure 5-26).

Routine Hip Exam for the Chronic Painful Hip

Aspiration and Joint Injection

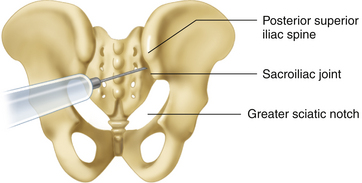

SACROILIAC JOINT

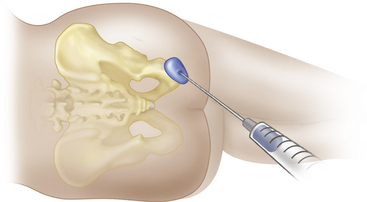

With the patient lying prone on a radiolucent table, the joint is approached from behind with a long spinal needle in the lower portion of the joint, just above the greater sciatic notch (Figure 5-27) and just below the PSIS. The needle is carefully advanced, slightly superiorly and laterally through the skin and subcutaneous tissue, at a 45° angle toward the affected SI joint. If bone is encountered, the needle is withdrawn and redirected more superiorly and laterally. After the needle enters the joint, aspiration and injection are performed.

HIP JOINT

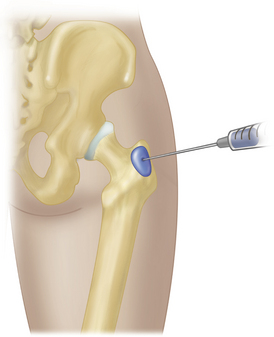

In the anterolateral approach, the needle is inserted along the femoral neck, beginning anterior and just inferior to the greater trochanter. The femoral neck is palpated with the needle until the capsule is entered, between 5 to 10 cm from the bone edge, depending on the size of the patient (Figure 5-28).

The hip joint lies approximately 2 to 3 cm lateral to the femoral artery, which can readily be palpated. In the anterior approach, the needle is inserted, under fluoroscopic guidance, approximately 2.5 cm lateral to the femoral artery and 2.5 cm distal to the inguinal ligament. The needle is advanced proximally and medially until the hip joint is entered, at 5 to 8 cm from the skin’s surface (see Figure 5-28).

BURSAE

Trochanteric Bursitis

With the patient lying on the nonpainful side, the greater trochanter is palpated to find the most tender area. The bursa is generally located in the posterolateral region. Once the area has been marked and prepared, a 25 gauge needle is inserted perpendicular to the skin, until the trochanter is reached, and then withdrawn slightly before a lidocaine-corticosteroid mixture is injected in a fan-shaped fashion (Figure 5-29). In most patients, a 1½ inch needle is adequate to reach the trochanter. In patients with greater adiposity, a longer needle may be required.

ISCHIOGLUTEAL BURSITIS

With the patient lying on the nonpainful side, hips and knees flexed, the site of greatest tenderness over the ischial tuberosity is identified. The needle is inserted at this site, and a lidocaine-corticosteroid mixture is injected, with care being taken to avoid needle-tip slippage off the tuberosity, which could injure the adjacent sciatic nerve (Figure 5-30).

Dreyfuss P., Dreyer S.J., Cole A., et al. Sacroiliac joint pain. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg.. 2004;12:225-265.

Gross J., Fetto J., Rosen E., editors. Musculoskeletal Examination, second ed., Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2002.

Hardcastle P., Nade S. The significance of the Trendelenburg test. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1985;67:741-746.

Harris N., Stanley D., editors. Advanced Examination Techniques in Orthopaedics. London: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Magee D.J. Orthopedic Physical Assessment, fourth ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002.

Narvani A.A., Tsiridis E., Kendall S., et al. A preliminary report on prevalence of acetabular labrum tears in sports patients with groin pain. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc.. 2003;11:403-408.

Rosenberg J.M., Quint T.J., de Rosayro M. Computerized tomographic localization of clinically guided sacroiliac joint injections. Clin. J. Pain. 2000;16:18-21.

Slipman C.W., Jackson H.B., Lipetz J.S., et al. Sacroiliac joint pain referral zones. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.. 2000;81:334-338.

Tile M., Hefet D.L., Kellam J.F. Fractures of the Pelvis and Acetabulum, Third ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

Vasudevan P.N., Vaidyalingam K.V., Nair P.B. Can Trendelenburg’s sign be positive if the hip is normal? J. Bone Joint Surg. Br.. 1997;79:462-466.