16 The hepatobiliary and gastrointestinal system

Biliary: Pertaining to the gallbladder and bile ducts.

Cholelithiasis: The presence of a common bile duct stone. Also called chronic cholangitis.

Diarrhea: Rapid movement of fecal matter through the large intestine.

Enteric System: The gastrointestinal tract.

Gastritis: Inflammation of the gastric mucosa.

Nausea: Conscious recognition of subconscious excitation in an area of the medulla closely related to the vomiting center.

Pancreatitis: Inflammation of the pancreas.

Peptic Ulcer: An excoriated area of the mucosa caused by the digestive action of gastric acid; frequently located in the first few centimeters of the duodenum.

Vomiting: A method for the gastrointestinal tract to rid itself of its contents when almost any part of the upper gastrointestinal tract becomes over irritated, distended, or excitable. The physical act of vomiting results when the muscles of the diaphragm and abdomen contract so that the gastric contents can be expelled.

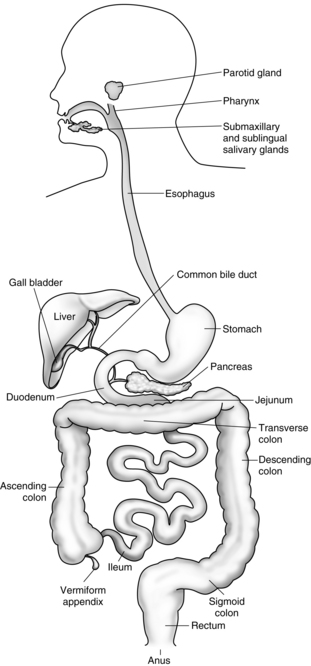

The esophagus

The esophagus is a pliable muscular tube that extends from the pharynx to the stomach (Fig. 16-1). It is located behind the trachea and in front of the thoracic aorta and traverses the diaphragm to enter the esophagogastric junction, sometimes called the cardia. Approximately 5 cm above the junction with the stomach is the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), a circular band of smooth muscle tissue, which functions to prevent the reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus. The normal resting pressure of the LES is approximately 30 torr. This pressure is maintained by stimulation provided by innervation from the vagus nerve. Ordinarily the sphincter remains constricted except during the act of swallowing. Anticholinergic drugs, such as atropine or glycopyrrolate, and pregnancy decrease the resting pressure of the lower esophagus. Drugs that increase the lower esophageal pressure include metoclopramide (Reglan) and antacids. The main function of the esophagus is to conduct ingested material to the stomach.1,2

Disorders of the esophagus

A hiatal hernia occurs when a portion of the upper stomach protrudes or herniates through the diaphragm. Ultimately this causes a stricture or narrowing to form where the diaphragm surrounds the stomach and causes a weakening of the LES. Symptoms of a hiatal hernia include chronic heartburn, pain, and vomiting. Patients with a hiatal hernia need constant observation for active and passive vomiting during the emergent phase of anesthesia. Monitoring patient with a hiatal hernia is especially important if the surgery was performed on an emergency basis when the patient had a full stomach.3

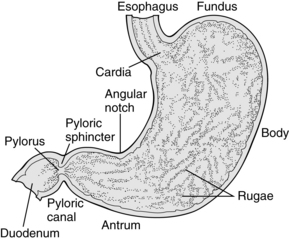

The stomach

The stomach can be anatomically divided into the following three sections: the fundus, the body, and the pyloric portion (Fig. 16-2). The fundus is the dome of the stomach, where peptic juice is secreted. The body is the middle portion of the stomach and is lined with parietal cells that secrete hydrochloric acid. The pH of the solution as secreted is approximately 0.8, which is extremely acidic. The total gastric secretion on a 24-hour basis is approximately 2 L. This volume normally has a pH of 1 to 3.5. Histamine has a major role in hydrochloric acid production by the parietal cells in the stomach, which is an effect mediated by histamine2 receptors, vagal stimulation, and the hormone gastrin. Activation on any one of these receptors potentiates the response of the other to stimulation. Blockade of the activated receptor produces a reduction in acid response because the potentiating effect of the stimulation is reduced. The third portion of the stomach is the pyloric portion, where a thick viscous mucus and the hormone gastrin are secreted. At the end of the antrum is the pylorus, an opening surrounded by a strong band of sphincter muscle that controls the amount of gastric contents that enter the duodenum.

FIG. 16-2 Anatomy of the stomach.

(From Hall JE: Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology, ed 12, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

Nervous and hormonal stimulation have profound effects on gastric volume and pH. More specifically, stimulation of the parasympathetic nervous system causes increased gastric secretion, and stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system causes decreased gastric secretion. Consequently, pain and fear, which activate the sympathetic nervous system, decrease gastric emptying. In addition, the administration of opioids and active labor prolong gastric emptying. Food, depending on the type and amount, passes through the stomach at a variable rate. For example, foods rich in carbohydrates pass through the stomach in a few hours, whereas proteins exit more slowly. The emptying time for fats is the slowest. Fluids, however, pass through the stomach rather rapidly. In fact, 90% of 750 mL of ingested saline solution exits the stomach within 30 minutes. In addition, 150 mL of fluids taken 1 or 2 hours before induction of anesthesia stimulates peristalsis and facilitates gastric emptying. Consequently, the small sips of water taken with the preoperative oral medications may in fact contribute to lower intraoperative and postoperative gastric volumes. It must be emphasized that fasting, regardless of the duration, does not guarantee that the stomach is completely empty of fluids or food.4,5

Effect of pregnancy on gastric motility and secretions

During pregnancy, many alterations occur as a result of the enlarged uterus and altered hormonal state. Because of the enlarged uterus, the stomach and intestine are moved cephalad and the axis of the stomach is shifted to a more horizontal position. The gastric emptying time is increased in women who are at least 34 weeks pregnant. In regard to the gastric volume and pH, no difference between pregnant and nonpregnant states seems to exist. Consequently, pregnant patients who have had nothing by mouth (NPO) for elective surgery do not have any additional risk of aspiration pneumonitis than do nonpregnant patients. However, research findings suggest that pregnant patients who have heartburn may be at greater risk for regurgitation and subsequent development of aspiration pneumonitis. In addition, if intramuscular opioids are given during labor, gastric emptying time is substantially delayed. Epidural anesthesia with local anesthetics does not seem to affect gastric volume or pH; however, if opioids are introduced into the epidural space, a delay in gastric emptying occurs.6,7

Postoperative nausea and vomiting

A great deal of research on PONV over the past few years has yielded drugs that have certainly improved the outcomes of the patient in regard to PONV. The 5-HT3 antagonists, such as ondansetron, tropisetron, granisetron, and dolasetron, competitively antagonize the effect of 5-HT at the 5-HT3 receptor site. Other drug therapies are the antihistamines (promethazine and dimenhydrinate), anticholinergics (scopolamine), neuroleptics (droperidol and triflupromazine), and glucocorticoids, such as dexamethasone. The pathophysiology and pharmacology of PONV is discussed at length in Chapter 29.

With recent research and the advent of new pharmacologic agents, the ability to prevent and efficaciously treat PONV has greatly improved, even for those patients at highest risk for these complications. Under the auspices of the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses, a multidisciplinary panel met to review current literature regarding the prevention and treatment of PONV and formulate a multimodal, multidisciplinary, evidenced-based set of guidelines to guide the practice of those taking care of surgical patients.8 Chief among these recommendations are that each patient should be assessed for the four evidenced-based risk factors for PONV (female gender, nonsmoker, a history of PONV or motion sickness, and administration of postoperative opioids); pharmacologic interventions should be based on the assessed risk for PONV; multimodal interventions, often consisting of more than one pharmacologic intervention targeting different drug receptors are superior to a single intervention; and rescue therapy should consist of administration of a different class of drug targeted at a different set of receptors than the ones given prophylactically.8

The incidence rate for this syndrome is higher in patients who had a full stomach at induction of anesthesia, who underwent intestinal or emergency surgery, or who have a suspected hiatal hernia. The best treatment is prevention. These patients should have a complete return of consciousness before the endotracheal tube is removed. If the endotracheal tube is to be removed in the PACU, the patient should be placed in a lateral position with the head down. Oxygen should be administered, and suction should be available for immediate use before the extubation is performed.9–12

The intestine

Sodium is absorbed by the small intestine at a rate of 25 to 35 g/day. This absorption accounts for approximately 16% of all the sodium in the body. When a patient has extreme diarrhea, sodium can be depleted to a lethal level within a few hours.13,14

The colon and rectum

Of surgical importance is the appendix, which arises from the cecum at its inferior tip. The appendix represents a special type of intestinal obstruction when it becomes inflamed by hyperplasia of submucosal lymphoid follicles, fecaliths, foreign bodies, or tumors.

The rectum functions entirely as an excretory canal and has no digestive function. It begins anatomically at the distal end of the sigmoid colon and ends at the anus. It is tubular and has two layers. The innermost layer is the lumen of the intestinal tract, and the outermost layer is skeletal muscle of the pelvic floor. The muscle is innervated by the parasympathetic nervous system.13

The liver

Drug biotransformation

The enzymes needed for oxidation and conjugation in the liver are called the microsomal enzymes. These enzymes are part of the cytochrome P-450 microsomal system. Exposure to certain drugs, including barbiturates and some anesthetics, can lead to an increase in the amount of microsomal enzymes in the liver. This process is commonly called enzyme induction. Enzyme induction increases the rate of drug biotransformation. Patients with severe liver disease may have reduced microsomal activity in the liver. As a result, drugs such as thiopental, diazepam, and meperidine have a prolonged action caused by a decreased rate of drug biotransformation by the microsomal enzymes. Consequently, patients with severe hepatic disease should be closely monitored for respiratory and cardiovascular depression in the PACU phase of the anesthetic experience.1,5

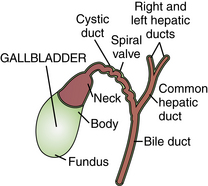

The gallbladder

The gallbladder is a thin-walled, pear-shaped organ attached to the inferior surface of the liver (Fig. 16-3) whose function is to store bile from the liver and release it into the small intestines to aid in the digestion of fats. Anatomically, it is divided into the fundus; the distal tip; the corpus (body), the middle body portion; the infundibulum, a pouch-like structure; and the neck, which leads to the cystic duct. The cystic duct joins the common hepatic duct to form the common bile duct. The common bile duct and the main pancreatic duct of Wirsung usually join at the choledochoduodenal junction, which is a passageway through the duodenal wall. The muscle of the choledochoduodenal junction is the sphincter of Oddi, which regulates the flow of bile into the duodenum. Many common opioid analgesics can produce spasm of the sphincter of Oddi and the duodenum and can increase the pressure in the biliary tree.

FIG. 16-3 Gallbladder and its extrahepatic ducts.

(From Buck CJ: 2012 ICD-9-CM professional edition, St. Louis, 2012, Saunders.)

Cholelithiasis is a common occurrence in patients with chronic gallbladder disease. As many as 20 million people have some form of cholelithiasis. Gallstones are composed of cholesterol, which is almost insoluble in pure water. The causes of gallstones include an excess of cholesterol in the bile, chronic inflammation of the epithelium, excessive absorption of bile acids from the bile, and excessive absorption of water from the bile. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is one of the most common abdominal surgeries and offers a clear advancement over the open removal of the gallbladder (see Chapters 40 and 47).15,16

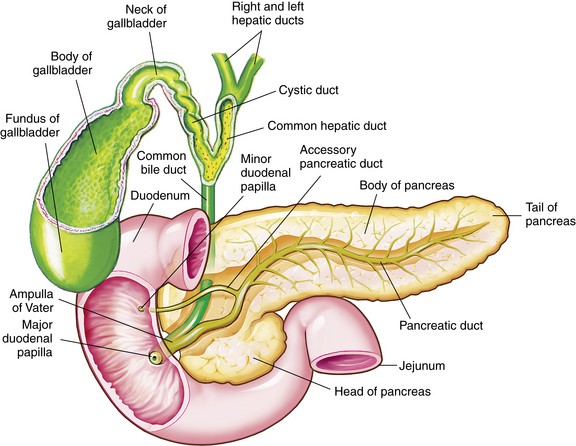

The pancreas

The pancreas is situated in the upper abdomen behind the stomach. It is a slender organ that consists of a head, a body, and a tail (Fig. 16-4). Its main duct, through which pass the pancreatic enzymes, runs the entire length of the gland and opens into the duodenum along with the common bile duct. Scattered throughout the pancreas are small clusters of cells called the islets of Langerhans. They are responsible for the production and secretion of hormones that they empty directly into the blood stream; therefore the islets of Langerhans are considered an endocrine gland. The following three types of cells are found in the islets of Langerhans: alpha, beta, and delta. The alpha cells are associated with the production of the hormone glucagon, and the beta cells are associated with insulin. The physiologic significance of the delta cells has not been determined.

FIG. 16-4 Associated structures of the gallbladder and pancreas.

(Modified from Thibodeau GA, Patton KT: Anatomy and physiology, ed 7, St. Louis, 2010, Mosby.)

Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis is a serious complication of surgery on the biliary tract. It can occur as a result of common duct exploration during gallbladder surgery. Acute postoperative pancreatitis should be suspected with excessive pain, vomiting, fever, tachycardia, persistent ileus, or jaundice. The perianesthesia nurse should be aware of these symptoms, which, if detected, should be reported to the surgeon. Treatment of this disorder may include nasogastric suction, anticholinergic drugs, antibiotics, and replacement of fluids and electrolytes.

The spleen

Normal health is possible after splenectomy because other tissues can assume the functions the spleen normally performs. Splenectomy is usually performed to cure or alleviate hematologic disease or because of its traumatic rupture. Because the spleen is friable and vascular, blood loss from a splenectomy can be high; therefore the perianesthesia nurse must assess the blood loss and the cardiovascular status of the patient during recovery (see Chapter 40).

Summary

The hepatobiliary and gastrointestinal systems are certainly multidimensional, and the understanding of the anatomy and physiology of these systems is essential to the perianesthesia nurse. The pathophysiologies of selected disorders that pertain to perianesthesia care were presented. Problems such as PONV (see Chapter 29), changes during pregnancy, and drug biotransformation were introduced. A complete overview of the care of the gastrointestinal, abdominal, and anorectal surgical patient is presented in Chapter 40.

1. Stoelting R. Pharmacology and physiology in anesthetic practice, ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

2. Evers A, Maze M. Anesthetic pharmacology: physiologic principles and clinical practice. ed 2. St. Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2011.

3. Hines RL, Marschall KE. Stoelting’s anesthesia and co-existing disease, ed 5. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008.

4. Barash P, et al. Clinical anesthesia, ed 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

5. Hall J. Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology, ed 12. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2011.

6. Miller R, et al. Miller’s anesthesia, ed 7. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

7. Stoelting R, Miller R. Basics of anesthesia, ed 6. St. Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2011.

8. American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses: ASPAN’S evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the prevention and/or management of PONV/PDNV. J Perianesth Nurs.2006;21(4):230–250.

9. Brunton L, et al. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, ed 12. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2010.

10. Hornby PJ. Central neurocircuitry associated with emesis. Am J Med. 2001;111(Suppl 8A):106S–112S.

11. Murphy M, et al. Identification of risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting in the perianesthesia adult patient. J Perianesth Nurs. 2006;21(6):377–384.

12. Odom-Forren J, et al. Evidence-based interventions for post discharge nausea and vomiting: a review of the literature. J Perianesth Nurs.2006;21(6):411–430.

13. Drake R, et al. Gray’s anatomy for students, ed 2. St. Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

14. Nagelhout J, Plaus K. Nurse anesthesia, ed 4. St. Louis: Saunders; 2009.

15. Hansen JT. Netter’s clinical anatomy, ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010.

16. Townsend CM, et al. Sabiston textbook of surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice. ed 19. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2012.