Chapter 35 THE HEPATITIS C-POSITIVE PATIENT

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Prevalence and natural history

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection varies worldwide with relatively low prevalence in North America and Europe compared with higher prevalence in Asia and southern Europe. The prevalence in Australia is approximately 0.1%, making HCV infection a common cause of chronic liver disease. Recent estimates from the Hepatitis C Projections Working Group 2006 suggest that around 200,000 people were chronically infected with the virus at the end of 2005 in Australia and that the prevalence will triple over the next 20 years. Of chronically infected individuals, 10%–15% will develop liver cirrhosis over a 20-year period. Once cirrhosis is established, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) develops at an annual incidence of 2%. In most countries where data are available, HCV infection is the leading cause of liver transplantation. The Hepatitis C Projections Working Group concluded that the current number of people receiving treatment would need to be increased three-fold to reduce the proportion of patients living with advanced liver disease due to HCV infection.

VIROLOGY

HCV is classified on the basis of similarity of nucleotide sequence into major genetic groups designated genotypes. A recent reclassification has resulted in six major genotypes with a number of subtypes that vary geographically. Genotypes 1, 2 and 3 are common in North America, Europe, Japan and Australia; genotype 4 is common in the Middle East including Egypt, genotype 5 in South Africa and genotypes 6 and its subtypes in Asia. All major genotypes have been identified in Australia, although genotypes 1 and 3 are more common.

CLINICAL COURSE OF HCV INFECTION

Acute HCV infection

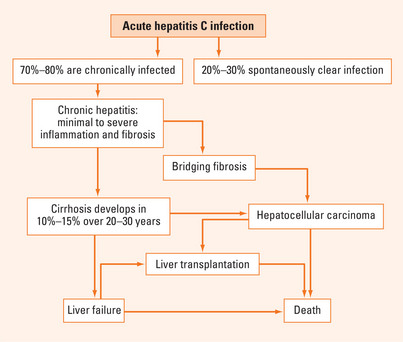

Acute HCV infection is commonly asymptomatic and thus infrequently recognised clinically. Systematic reviews suggest that approximately 25% of patients may spontaneously clear acute HCV infection although the exact proportion is unclear. Acute HCV may be associated with a clinical syndrome of fatigue, lethargy, low-grade fever and right upper quadrant discomfort. Serum HCV RNA typically becomes detectable 7–21 days after exposure and specific antibodies appear subsequently. Jaundice occurs in less than 20% of acute infections. Interestingly, the patients who develop clinically apparent acute hepatitis clear the virus and avoid chronic disease with greater frequency than those who have clinically silent disease (see Treatment section). The host and viral factors that influence resolution of HCV infection remain unclear.

Chronic HCV infection

The majority of persons exposed to HCV will develop chronic infection with persistence of detectable serum HCV RNA for more than 6 months. A certain proportion of these patients will have persistently normal liver function tests; in these patients the risk of progression to advanced liver diseases is low. In patients with abnormal alanine aminotransferase (ALT), the overall fibrosis progression rates are higher and some will progress through increasing stages of fibrosis to cirrhosis (Figure 35.1).

Complications of chronic HCV infection

Progression to hepatocellular carcinoma

The risk of HCC is increased 25-fold in HCV-infected patients compared with HCV-negative controls. Virtually all HCV-related HCC cases occur among patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. The annual risk of HCC development in patients with HCV cirrhosis is 1%–4% in Western populations and higher in Asian populations (up to 7%). Factors affecting progression to HCC include male gender, older age, duration of HCV infection (most cases occur after 25–30 years of chronic infection), daily alcohol intake >60 g (>6 standard alcoholic drinks/day) and coinfection with HBV.

TREATMENT

Interferon and ribavirin

Interferons are naturally occurring antiviral proteins that produce an ‘antiviral state’ to promote elimination of virally infected cells. Jay Hoofnagle and colleagues first reported using recombinant alpha interferon to treat non-A, non-B hepatitis in 1986. John McHutchison and colleagues showed in 1998 that the addition of ribavirin, a guanosine analogue, in combination with interferon reduced the relapse rate following the end of therapy, and thus improved the overall sustained response rate. The precise mechanism of ribavirin’s antiviral activity is unknown; it is ineffective against HCV when given alone. Currently the combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin is the international standard of therapy for patients with chronic HCV infection. Addition of polyethylene glycol (pegylation) to the interferon molecule allows for weekly administration; ribavirin tablets are taken daily in divided doses.

Treatment regimens

For patients with chronic HCV infection, the recommended treatment duration with pegylated interferon and ribavirin varies by genotype. Patients with genotype 1 should receive treatment with either peginterferon alfa-2a (180 μg weekly) or peginterferon alfa-2b (1.5 μg/kg weekly) plus weight-based ribavirin daily for 12 months. Patients with genotypes 2 and 3 should receive the same interferon dosages plus ribavirin for 6 months; recent data suggest that a ribavirin dose of 800 mg/day is sufficient for these patients. Unfortunately, there are few data to guide therapy for patients with genotypes 4, 5 and 6, although it is generally thought that patients with genotype 4 require therapy for 12 months and patients with genotype 6 may only require treatment for 6 months. The overall SVR rate following therapy with pegylated interferon and ribavirin is approximately 55%; patients with genotype 1 have lower response rates than patients with non-1 genotypes. There is currently no consensus on the most effective treatment for patients who have either relapsed or failed to respond to pegylated interferon plus ribavirin.

Treatment with interferon may be individualised by considering genotype and, more recently, viral kinetics during therapy (see Table 35.1). Patients with genotype 1 who achieve an early virological response (EVR), generally defined as ≥2 log reduction in HCV RNA by week 12, are more likely to achieve an SVR compared with patients who do not reach this threshold. Those patients who achieve a 2 log reduction by week 12 should continue therapy until week 24; if they have undetectable HCV RNA by qualitative PCR at that time, then they should continue therapy until week 48. Patients who fail to achieve an EVR or who have detectable HCV RNA at week 24 should stop treatment, since the likelihood of achieving a SVR is less than 2%. Recent studies have looked at shortening treatment duration in genotype 1 patients with low pretreatment viral loads (Table 35.1) and prolonging treatment duration in genotype 1 patients with high viral loads.

| Genotype 1 | |

| Week 12 | Quantitative HCV RNA ≤2 log reduction → Discontinue therapy |

| Quantitative HCV RNA ≥2 log reduction → Continue therapy to week 24 | |

| Week 24 | Qualitative HCV RNA detectable → Discontinue therapy |

| Qualitative HCV RNA undetectable → Continue therapy to week 48 | |

| Week 48 | End of therapy—check HCV RNA by qualitative PCR |

| Week 72 | End of follow-up—check HCV RNA by qualitative PCR (this determines sustained virological response or relapse) |

| Recent developments: | |

HCV = hepatitis C virus; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; RNA = ribonucleic acid; SVR = sustained virological response.

Adverse events associated with treatment

Ribavirin

Prior to commencing therapy patients should have a baseline full blood examination, urea, electrolytes, creatinine, thyroid function tests and pregnancy testing. Patients with diabetes or hypertension should have an ophthalmological examination. Counselling prior to treatment and ongoing support during treatment are important in helping patients adhere to a difficult treatment regimen; those patients who complete a course of treatment have the best chance of eradicating HCV.

SUMMARY

The pandemic of hepatitis C remains an important public health issue and a major challenge to individual patients in regard to understanding the impact of this chronic viral infection on their health and in making a decision whether to undertake a demanding treatment regimen. The international standard therapy is a combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin, which achieves viral eradication in 55% of patients overall, although this proportion varies with genotype and viral load. Individualisation of treatment is possible based on virological responses during therapy in different genotype groups. Treatment is associated with significant adverse effects so that ongoing medical and nursing support is required. A number of new treatment approaches, based on direct antiviral agents and immune manipulation, are likely to improve patient outcomes in the future.

De Francesco R, Migliaccio G. Challenges and successes in developing new therapies for hepatitis C. Nature. 2005;436:953-960.

Halfon P, Penaranda G, Bourliere M, et al. Assessment of early virological response to antiviral therapy by comparing four assays for HCR RNA quantitation using the international unit standard: implications for clinical management of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Med Virol. 2006;78:208-215.

Hoofnagle JH, Mullen KD, Jones DB, et al. Treatment of chronic non-A, non-B hepatitis with recombinant human alpha interferon. A preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1575-1578.

Manns M, Wedemeyer H, Cornberg M. Treating viral hepatitis C: efficacy, side effects and complications. Gut. 2006;55:1350-1359.

McCaughan G, George J. Fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gut. 2004;53:318-321.

McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schif ER, et al. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485-1492.

Micallef J, Kaldor J, Dore G. Spontaneous viral clearance following acute hepatitis C infection: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Viral Hep. 2006;13:34-41.

Prati D. Transmission of hepatitis C virus by blood transfusions and other medical procedures: a global review. J Hepatol. 2006;45:607-616.