Chapter 36 THE HEPATITIS B-POSITIVE PATIENT

INTRODUCTION

At least 350 million people worldwide are chronically infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV).

THE ANTIGENS AND THEIR ANTIBODIES

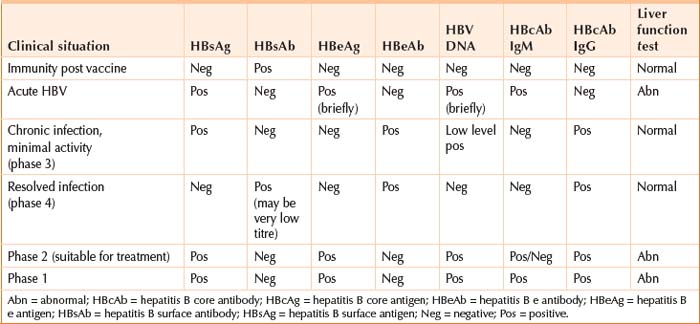

Table 36.1 and Figure 36.1 summarise the tests available for HBV and their clinical relevance. There are three antigens, and each has corresponding antibodies:

TRANSMISSION OF HBV

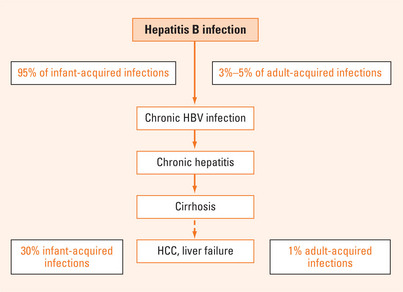

HBV is highly infectious in someone who has replicating virus—the virus will be present in all body fluids at high concentration. There are two main settings for HBV transmission. The most common global setting is transmission in early life in a highly endemic area (i.e. most parts of the world except the highly Westernised countries of Western Europe, USA, Canada and Australia). Transmission can occur from mother to baby (95% likelihood in mother with replicating HBV). Babies who do not acquire it from their mothers in these areas have a high chance of being infected by other members of the extended family within the first year of life. Such young children do not develop symptoms, but remain subclinical for the first few decades of life (Figures 36.2 and 36.3). Most people in these endemic regions are either carriers or immune by adult life. Such transmission is responsible for most of the world’s burden of HBV-related disease.

The second setting is transmission in adolescence or adult life by more ‘Western’ practices, such as injecting drug use, and sexual contact. Other risk factors are listed in Table 36.2.

TABLE 36.2 Some risk factors for acquisition of hepatitis B virus

NATURAL HISTORY OF HEPATITIS B

The outcome of hepatitis B depends almost entirely on the age of infection: young babies and children have a 90% chance of becoming a chronic carrier, but adults have less than 10% chance (Figure 36.2). The individual infected as a baby has an eventual 30% chance of dying from the consequences of hepatitis B (females 15%; males 45%), whereas the person who has acquired the infection in adult life has <1% chance. The reasons for this difference are the duration of the replicative or ‘highly infectious’ phase of the infection: this is related, in turn, to the level of immunological maturity of the host.

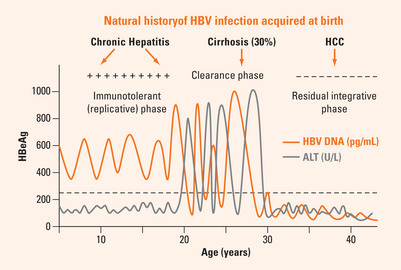

Infection acquired in early life: the three phases

Infection acquired early in life is the most common setting worldwide. The HBV is not recognised as a foreign protein until immunological maturity, generally between 15 and 40 years. Consequently, during the first two, three or four decades of life the virus continues to replicate, but there is no immune response i.e. transaminases are normal, and histology virtually normal—this is the immunotolerant replicative phase. At a variable age, often around 20 years, ‘hepatitis’ develops for the first time (i.e. transaminases rise). This is the beginning of the ‘e antigen clearance phase’. This phase can be quick, with rapid development of e antibody and minimal hepatitis, or prolonged, with ongoing cycles of regeneration and repair, leading to cirrhosis in 30% of cases. During these flares, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) will rise and the DNA will temporarily fall, only to rise again with the next flare. Eventually the third phase, the residual integrative phase, will be reached. By this stage 30% of people will have significant liver injury, but this is usually not clinically apparent for some time. Thus, people in this phase must be regarded as potentially having cirrhosis, which may be detectable only on liver biopsy.

On occasion, the e antigen clearance phase will be partially resolved by development of a mutant strain, selected out under immunological pressure—pressure which has suppressed the wild-type virus, but allowed mutations to replicate. The most common mutations are known as the precore mutant, relating to specific mutations in the precore region of the genome, and the basal core promoter mutations. These strains are more likely to develop with certain genotypes (strains) of HBV, which have geographical variation. The precore and basal core promoter mutations are unable to produce e antigen (Table 36.3) although they continue to replicate and cause significant liver damage.

TABLE 36.3 The diagnosis of wild type and precore mutant HBV

| Wild type | Precore | |

| HBsAg | Positive | Positive |

| HBeAg | Positive | Negative |

| Anti-e | Negative | Positive |

| DNA | Positive | Positive |

| ALT | Elevated | Elevated |

Diagnosis and clinical significance of the three phases

The phase of infection in a chronic HBV carrier can be identified by ordering three blood tests. Generally, in this situation, the surface antigen has already come back positive, and long-standing infection is suspected because of the clinical setting (e.g. born in highly endemic region). The blood tests to order are ALT, HBV DNA and HBe antigen/antibody. The phases of infection (Figure 36.3) are detailed below.

Hepatitis B acquired in adolescence or adult life: resolved infection

In this setting, characteristic of infection in the ‘Western’ world, the host has reached immunological maturity, there is no immunotolerant replicative phase, and he/she and enters the ‘clearance phase’ immediately. Thus, there is a high chance of clearing hepatitis B surface antigen within 6 months (Figure 36.1; Table 36.1). Following this most individuals will have markers of the resolution phase only and, in general, the chance of liver disease or HCC is very low.

HEPATITIS B IN PRACTICE

Three common scenarios are usually encountered, and each scenario prompts specific questions.

Scenario 1: The ‘healthy’ or asymptomatic chronic carrier

What phase of infection are they in?

Order ALT, HBV-DNA, HBeAg/eAb.

Scenario 2: the chronic carrier with liver disease

All of the above questions are relevant as well as the following.

Scenario 3: acute hepatitis B

When to suspect?

Investigation

Remember that there may be alternative or additional causes for jaundice in a chronic HBV carrier—in other words, this current episode may not be acute HBV. Thus, investigations should include a detailed drug history (prescribed and non-prescribed), testing for hepatitis C (by serology and polymerase chain reaction [PCR]), testing for hepatitis D (which can coinfect or superinfect those people with HBV), testing for hepatitis A and E, Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus. Also test for Wilson’s disease, iron studies and autoimmune hepatitis.

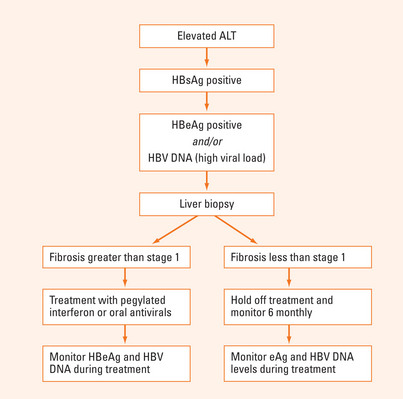

ANTIVIRAL TREATMENT

Table 36.4 compares interferon and nucleoside analogue therapy. Interferon affords a chance of long-term remission to selected patients, at the cost of side effects. Antiviral therapy is often beset by frequent resistance with need to change antivirals. Thus these patients need to be monitored every 3 months with HBV DNA and liver function tests and future trials may indicate a benefit from combination antiviral treatment in preventing resistance.

| Interferon | Antivirals | |

| Route | Subcutaneous | Oral |

| Duration of treatment | 24 weeks | Open-ended |

| Side effects | Marked | Minimal |

| Risk of resistance | No | Yes |

| Effectiveness in selected patients | 30% | 30% at 2 years |

| Precore mutant disease | Minimal effectiveness | Requires long-term treatment, risk of resistance |

| Can be used sequentially | Yes, prior to antivirals | Yes, prior to other antivirals as resistance develops |

SUMMARY

On a global scale, chronic hepatitis B infection is common, affecting approximately 3.5 million people. The are two main settings for HBV transmission: transmission in early life in a highly endemic area (mother to baby or infection by other members of the extended family within the first year of life) or transmission in adolescence or adult life by injecting drug use and sexual contact. The presence of HBsAg indicates current infection, whereas the presence of HBsAb indicates immunity. The presence of HBeAg indicates active viral replication. HBV DNA measurements provide a viral load and are a useful means of monitoring the adequacy of response to therapy. While most infected individuals develop adequate immunity, a smaller proportion become ‘carriers’ and an even smaller number develop chronic active hepatitis. The latter may lead to the development of cirrhosis and HCC. Patients with chronic active hepatitis need to be assessed for treatment. Such therapies include peginterferon alpha-2a and oral nucleoside/nucleotide analogues. They not only require long-term ongoing treatment, but are associated with the development of viral resistance. Patients are at risk of progressing to cirrhosis and HCC. Those with progressive cirrhosis may benefit from liver transplantation. Six-monthly HCC monitoring is best targeted at patients with cirrhosis. Vaccination is the best strategy for preventing this infection.

Hoofnagle JH. Hepatitis B-preventable and now treatable. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1074-1076.

Jacobson IM. Therapeutic options for chronic hepatitis B: considerations and controversies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(Suppl 1):S13-S18.

McMahon BJ. Selecting appropriate management strategies for chronic hepatitis B: who to treat. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(Suppl 1):S7-S12.

Perrillo RP, Gish RG, Peters M, et al. Chronic hepatitis B: a critical appraisal of current approaches to therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:233-248.