Chapter 6

The Head and Neck

A lady, aged twenty, became affected with some symptoms which were supposed to be hysterical. … After she had been in this nervous state about three months it was observed that her pulse had become singularly rapid. … She next complained of weakness on exertion and began to look pale and thin. … It was observed that the eyes assumed a singular appearance, for the eyeballs were apparently enlarged. In a few months … a tumour, of a horseshoe shape, appeared on the front of the throat and exactly in the situation of the thyroid gland.

Robert James Graves (1796–1853)

General Considerations

The appearance of the head and face, their contours and texture, often provides the first insight into the nature of illness. Sunken cheeks, wasting of the temporal muscles, and flushing of the face are important visible clues of systemic illness. Some facial appearances are pathognomonic of disease. The pale, puffy face of nephritis, the startled expression of hyperthyroidism, and the immobile stare of parkinsonism are examples of classic facies.

The appearance of the patient’s face may also provide information regarding psychologic makeup: is the person happy, sad, angry, or anxious?

Thyroid disease takes many forms. The World Health Organization estimates that more than 200 million people in the world have enlarged thyroid glands, a condition known as goiter. Asians first described goiter around 1500 BCE. Even at that time, they recognized that seaweed in the diet tended to make goiters smaller. Iodine was not discovered until the nineteenth century, but it is now believed that those goiters were related to an iodine deficiency that was partially corrected by the iodine in the seaweed.

The ancient Greeks and Romans recognized that when a thin thread tied around the neck of a newly married woman broke, she was pregnant. This was caused by an increase in the size of the thyroid during pregnancy.

Thyroid cancer is the most common endocrine cancer, and its incidence has increased by approximately 3% per 100,000 people per year. In 2011, there were 48,020 new cases of thyroid cancer. Of these new cases, approximately 11,470 occurred in men and 36,550 occurred in women. Thyroid is the fifth leading site of new cancers in women. The incidence rate of thyroid cancer has been increasing sharply since the mid-1990s, and it is the fastest increasing cancer in both men and women. There were 1740 deaths in 2011 from thyroid cancer: 760 in men and 980 in women. The death rate for thyroid cancer has been increasing in men and stable in women. Risk factors include radiation exposure related to medical treatment during childhood. The 5-year survival rate for all thyroid cancer patients is 97%. Survival, however, varies markedly by stage, age of diagnosis, and disease subtype. The 5-year survival rate approaches 100% for localized disease, is 97% for regional stage disease, and 58% for distant stage disease.

In the United States, cancer of the head and neck constitutes approximately 5% of all malignancies in men and 3% in women. Head and neck cancer includes cancers of the mouth, nose, sinuses, salivary glands, throat, and lymph nodes in the neck. Most begin in the moist tissues that line the mouth, nose, and throat. Symptoms include a lump or sore in the mouth that does not heal, a persistent sore throat, trouble swallowing, or a change or hoarseness in the voice. Using tobacco or alcohol increases the risk of developing head and neck cancer. In fact, 85% of all head and neck cancers are linked to tobacco use. If found early, these cancers may be curable. Treatment can include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or a combination, but these treatments may affect eating, speaking, or even breathing.

In 2011, there were 39,400 (27,710 men and 11,690 women) new cases of head and neck cancer and 7900 related deaths. It has been estimated that nearly 90% of these cases are associated with poor dental hygiene, tobacco use, exposure to nickel, and alcohol use. Tobacco, whether chewed, smoked, or simply kept in the buccal pouch, predisposes an individual to tumors of the upper aerodigestive tract. Pipe smokers and tobacco chewers are at risk for tumors of the oral cavity, and the Chinese are at risk for nasopharyngeal carcinomas. On the basis of rates from 2002 to 2004, it is estimated that 1.02% of both sexes born in 2007 in the United States will receive diagnoses of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx at some time during their lifetime.

Structure and Physiology

The Head

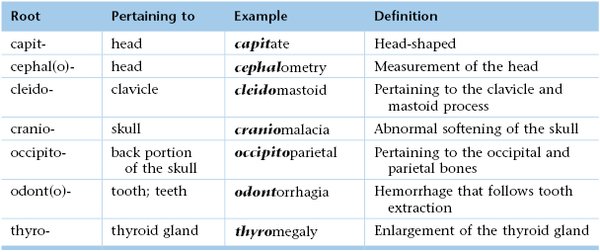

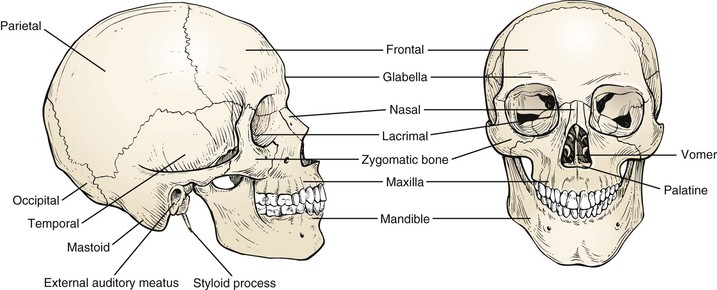

The skull is composed of 22 bones, 14 in the face alone. This bony structure acts as a support and protection for the softer tissues within.

The facial skeleton is composed of the mandible; the maxilla; and the nasal, palatine, lacrimal, and vomer bones. The unpaired mandible forms the lower jaw. The maxilla is an irregular bone and forms the upper jaw on each side. The nasal bones form the bridge of the nose. The other bones are not relevant to this discussion.

The main bones of the cranial skeleton include the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital bones. The frontal bones form the forehead. The temporal bones form the anterolateral walls of the brain. The mastoid process, which is part of the temporal bone, is particularly important in ear disease and is discussed in Chapter 8, The Ear and Nose. The parietal bones form the top and posterolateral portions of the skull. The occipital bones form the posterior portion of the skull. The bones of the face and skull are shown in Figure 6-1.

Figure 6–1 Bones of the face and skull.

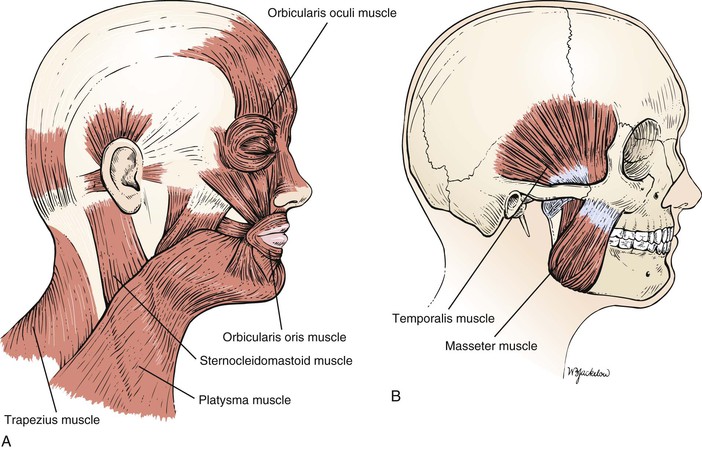

The orbicularis oculi muscle surrounds the eye. Its function is to close the eyelids. This muscle and its action are further discussed in Chapter 7, The Eye.

The platysma is a thin, superficial muscle of the neck, crossing the outer border of the mandible and extending over the lower anterior portion of the face. The main action of the platysma is to pull the mandible downward and backward, which results in a mournful facial expression.

The muscles of mastication include the masseter, pterygoid, and temporalis. These muscles insert on the mandible and effect chewing. The masseter is strong and thick and is one of the most powerful muscles of the face. The action of the masseter is to close the jaw by elevating and drawing the mandible backward. Tension in the masseter may be felt by clenching the jaw. Although important to jaw function, the other muscles of mastication are not clinically relevant to physical diagnosis and are not discussed here. The locations of these muscles are shown in Figure 6-2.

Figure 6–2 Muscles of the face and skull. A, The more superficial muscles. B, The underlying muscles.

The trigeminal, or fifth cranial, nerve carries sensory fibers from the face, oral cavity, and teeth and carries efferent motor fibers to the muscles of mastication. The major divisions of this nerve are discussed in subsequent chapters.

The Neck

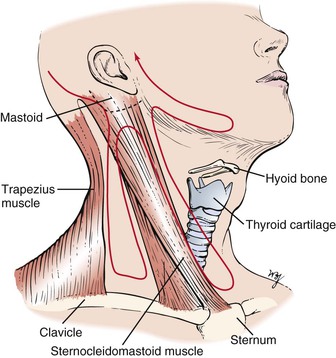

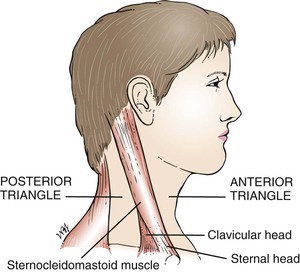

The neck is divided by the sternocleidomastoid muscle into the anterior, or medial, triangle and the posterior, or lateral, triangle. These are illustrated in Figure 6-3.

Figure 6–3 Boundaries of the triangles of the neck.

The sternocleidomastoid is a strong muscle that serves to raise the sternum during respiration. The sternocleidomastoid has two heads: The sternal head arises from the manubrium sterni, and the clavicular head originates on the sternal end of the clavicle. The two heads unite and insert on the lateral aspect of the mastoid process. The sternocleidomastoid is innervated by the spinal accessory, or eleventh cranial, nerve.

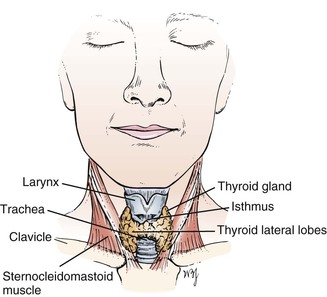

The thyroid gland envelops the upper trachea and consists of two lobes connected by an isthmus. It is the largest endocrine gland in the body. As seen from the front, the thyroid is butterfly-shaped and wraps around the anterior and lateral portions of the larynx and trachea, as shown in Figure 6-4.

Figure 6–4 Thyroid gland.

The thyroid isthmus lies across the trachea just below the cricoid cartilage of the larynx. The lateral lobes extend along both sides of the larynx, reaching the middle of the thyroid cartilage of the larynx. On occasion, the thyroid gland may extend downward and enlarge within the thorax, producing a substernal goiter. The function of the thyroid gland is to produce thyroid hormone in accordance with the needs of the body.

The pharynx and larynx are discussed in Chapter 9, The Oral Cavity and Pharynx.

The sternocleidomastoid muscle overlies the carotid sheath. The carotid sheath lies lateral to the larynx. This sheath contains the common carotid artery, the internal jugular vein, and the vagus nerve.

Posterior to the sternocleidomastoid is the posterior triangle. This is bounded by the trapezius muscle posteriorly and by the clavicle inferiorly. The posterior triangle also contains lymph nodes.

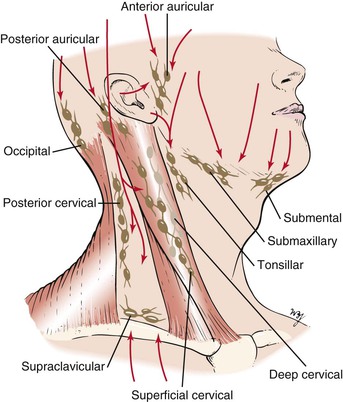

It has been estimated that the neck contains more than 75 lymph nodes on each side. The chains of these lymph nodes are named for their location. Starting posteriorly, they are the occipital, posterior auricular, posterior cervical, superficial and deep cervical (adjacent to the sternocleidomastoid muscle), tonsillar, submaxillary, submental (at the tip of the jaw in the midline), anterior auricular, and supraclavicular (above the clavicle) chains. Knowledge of lymphatic drainage is important because the presence of an enlarged lymph node may signal disease in the area draining into it. The main groups of lymph nodes and their drainage areas are shown in Figure 6-5.

Figure 6–5 Lymph nodes of the neck and their drainage.

Review of Specific Symptoms

The most common symptoms related to the neck are as follows:

Neck Mass

The most common symptom is a lump or swelling in the neck. Once a patient complains of a neck lump, ask the following questions:

“When did you first notice the lump?”

“Does the lump change in size?”

“Have you had any ear infections? Infections in your mouth?”

“Has there been hoarseness associated with the mass?”

“Is there a family history of thyroid cancer?”

“Is there a history of prior neck or thyroid gland radiation?”

If there is associated pain with a mass in the neck, an acute infection is likely. Masses that have been present for only a few days are commonly inflammatory, whereas those present for months are more likely to be neoplastic. A mass that has been present for months to years without any change in size often turns out to be a benign or congenital lesion. Blockage of a salivary gland duct may produce a mass that fluctuates in size while the patient eats.

The age of the patient is relevant in the assessment of a neck mass. A lump in the neck of a patient younger than 20 years of age may be an enlarged tonsillar lymph node or a congenital mass. If the mass is in the midline, it is most likely to be a thyroglossal cyst.1

From the ages of 20 to 40 years, thyroid disease is more common, although lymphoma must always be considered. When a patient is older than 40 years of age, a neck mass must be considered malignant until proved otherwise.

The location of the mass is also important. Midline masses tend to be benign or congenital lesions, such as thyroglossal cysts or dermoid cysts. Lateral masses are frequently neoplastic. Masses located in the lateral upper neck may be metastatic lesions from tumors of the head and neck, whereas masses in the lateral lower neck may be metastatic from tumors of the breast and stomach. One benign lateral neck mass is a branchial cleft cyst, which may manifest as a painless neck mass near the anterior upper third border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Hoarseness associated with a thyroid nodule is suggestive of vocal cord paralysis resulting from impingement of the recurrent laryngeal nerve by tumor.

Neck Stiffness

If a patient complains of a stiff neck, ask the following questions:

“How long have you had the stiff neck?”

“Have you done any strenuous activity recently?”

“Are you aware of sleeping differently before the stiff neck occurred?”

“Do you have a headache associated with the stiff neck?”

“Have you had recent nausea or vomiting?”

A stiff neck is typically characterized by soreness and difficulty moving the neck, especially when trying to turn the head to the side. A stiff neck may also be accompanied by a headache, neck pain, shoulder pain, or arm pain, and, in severe cases, may cause the individual to turn the entire body as opposed to the neck when trying to look sideways or backwards. By far the most common cause of a stiff neck is a muscle sprain or muscle strain, particularly to the levator scapula muscle. Located at the back and side of the neck, the levator scapula muscle connects the cervical spine (the neck) with the shoulder. This muscle is controlled by the third and fourth cervical nerves (C3, C4).

The levator scapula muscle may be strained or sprained throughout the course of many common activities, such as sleeping in a position that strains the neck muscles, sports injuries, rapid swimming, poor posture, stress, or holding the neck in an abnormal position for a long period.

The sudden occurrence of stiff neck, high fever, nausea, vomiting, sleepiness, or headache should raise suspicion of possible meningeal irritation. Any time a stiff neck is accompanied by a fever it is advisable to seek medical evaluation.

Neck pain may be associated with referred pain from the chest. Patients with angina or a myocardial infarction may complain of neck pain or neck stiffness.

Effect of Head and Neck Disease on the Patient

The concept of body image is important. The head and neck are the most visible portions of the body. The shape of the eyes, mouth, face, and nose is very important to people. Many dislike their body image and want to change it by cosmetic surgery. Others require cosmetic surgery to repair alterations caused by trauma. Still others suffer from disfiguring head and neck cancer and need to undergo surgical procedures for the removal of these lesions. Many of these procedures are themselves mutilating.

Distortion of the body image, especially on the head and neck, can have a devastating effect on the patient. The most common reaction to head and neck disease is depression. Many affected patients suffer from feelings of sadness and hopelessness. They look in the mirror hoping that someday they will see themselves with a more acceptable body image. Recurrent thoughts of suicide are common. Many of these depressed patients turn to alcohol or other drugs.

On occasion, patients who have undergone cosmetic surgery are dissatisfied with the results. Many of these patients are trying to escape from feelings of inferiority and social maladjustment. They may have had only minor defects, but they viewed those defects as a major source of their interpersonal problems. Cosmetic surgery is a way to change their image in the hope of improving their social maladjustment. Some individuals may even blame their physicians for “destroying” their faces. Even after further revisions, these patients may never be satisfied. One of the keys to successful cosmetic surgery is the proper psychological evaluation of patients.

Physical Examination

No special equipment is needed for the examination of the head and neck. It is performed with the patient seated, facing the examiner. The examination consists of the following steps:

• Auscultation for carotid bruits (discussed in Chapter 12, The Peripheral Vascular System)

Inspection

Inspect the position of the head. Does the patient hold the head erect? Is there any asymmetry of the facial structure? Is the head in proportion to the rest of the body?

Inspect the scalp for lesions. Describe the hair.

Are any masses present? If so, describe their size, consistency, and symmetry. Figure 21-42 depicts a child with a midline thyroglossal duct cyst. The cyst is smooth, firm, and midline. When the patient is asked to swallow or stick out the tongue, the thyroglossal duct cyst moves upward.

The thyroid gland in an embryo actually starts as a small group of cells at the very back of the base of the tongue. The base of the tongue is the posterior one third of the tongue. The furthest point backward is where the thyroid begins to develop. From here, in the earliest weeks of gestation the thyroid cells begin a journey downward along the midline of the neck until they arrive low in the neck just above the sternum. These cells then grow into the butterfly-shaped gland that we recognize as the thyroid gland. The tubelike path that these cells took to get their final destination then closes. If it doesn’t close in its entirety, it may leave an open space that may fill up with fluid or a thick mucouslike material. This fluid-filled sac is called a thyroglossal duct cyst.

Thyroglossal duct cysts usually make themselves known early in life, either in childhood or young adulthood. They are usually a round or oval soft mass found in the midline of the neck (or a little to the left of the midline) just above the larynx.

Most commonly thyroglossal duct cysts are approximately the size of a ping pong ball, but they can get much larger. If they get infected, the skin may turn red and become tender, and sometimes these cysts will spontaneously rupture through the skin and the fluid and pus within will drip down the neck. Avoiding infection is one of the primary reasons to remove these cysts.

One must always determine whether the thyroglossal duct cyst contains any thyroid tissue. The reason the presence of thyroid tissue is important is twofold. First, in a rare patient, it may be that the thyroid tissue in a thyroglossal duct cyst is the entire thyroid gland that did not make its normal descent to its correct anatomic location lower down in the neck. For this reason it is important to make sure the patient has a normal thyroid gland as well as the cyst. Second, thyroid cancer can exist in thyroid tissue within a thyroglossal duct cyst.

Inspect the eyes for proptosis (a forward displacement, or bulging, of the eyeball). Proptosis may be caused by thyroid dysfunction or by a mass in the orbit.

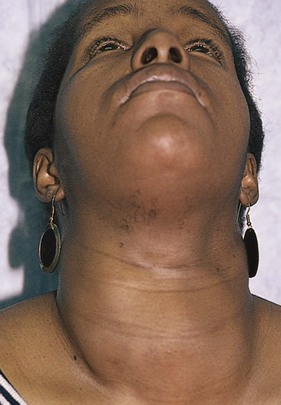

Inspect the neck for areas of asymmetry. Ask the patient to extend the neck so that the neck can be inspected for scars, asymmetry, or masses. The normal thyroid is barely visible. Ask the patient to swallow while you observe any upward motion of the thyroid with swallowing. A diffusely enlarged thyroid gland often causes generalized enlargement of the neck. A patient with diffuse thyromegaly is pictured in Figure 6-6. This patient has Graves’ disease with bilateral proptosis.

Figure 6–6 Graves’ disease.

Is nodularity of the neck present? Nodular neck masses caused by a multinodular goiter are pictured in Figure 6-7.

Figure 6–7 Multinodular goiter.

Is superficial venous distention present? It is important to evaluate venous distention in the neck because it may be associated with a goiter.

Palpation

Palpate the Head and Neck

Palpation confirms the information obtained by inspection. The patient’s head should be slightly flexed and cradled in the examiner’s hands, as demonstrated in Figure 6-8.

Figure 6–8 Palpation of the head and neck.

All areas of the cranium should be palpated for tenderness or masses. The pads of the examiner’s fingers should roll the underlying skin over the cranium in circular motions to assess its contour and to feel for the presence of lymph nodes or masses. Starting from the occipital region, the examiner’s hands are moved into the posterior auricular region, which is superficial to the mastoid process; down into the posterior triangle to feel for the posterior cervical chain; along the sternocleidomastoid muscle to feel for the superficial cervical chain; hooking around the sternocleidomastoid muscle to feel for the deep cervical chain deep to the muscle; into the anterior triangle region; up to the jaw margin to feel for the tonsillar group; along the jaw to feel the submaxillary chain; to the tip of the jaw for the submental nodes; and up to the anterior auricular chain in front of the ear. This sequence of examination is shown in Figure 6-9.

Enlarged posterior auricular and posterior cervical nodes are pictured in Figure 6-10.

Any nodes that are palpated should be observed for mobility, consistency, and tenderness. Tender lymph nodes are suggestive of inflammation, whereas fixed, firm nodes are consistent with a malignancy.

Palpate the Thyroid Gland

There are two approaches to palpating the thyroid gland. The anterior approach is carried out with the patient and examiner sitting face to face. By flexing the patient’s neck or turning the chin slightly to the right, the examiner can relax the sternocleidomastoid muscle on that side, making the examination easier to perform. The examiner’s left hand should displace the larynx to the left, and during swallowing, the displaced left thyroid lobe is palpated between the examiner’s right thumb and the left sternocleidomastoid muscle. This is demonstrated in Figure 6-11. After the left lobe has been evaluated, the larynx is displaced to the right, and the right lobe is evaluated by reversing the hand positions.

At this point in the examination, the examiner should stand behind the patient to palpate the thyroid by the posterior approach. In this approach, the examiner places two hands around the patient’s neck, which is slightly extended. The examiner uses the left hand to push the trachea to the right. The patient is asked to swallow while the examiner’s right hand rolls over the thyroid cartilage. As the patient swallows, the examiner’s right hand feels for the thyroid gland against the right sternocleidomastoid muscle. The patient is again asked to swallow as the trachea is pushed to the left, and the examiner uses his or her left hand to feel for the thyroid gland against the patient’s left sternocleidomastoid muscle. The patient should be given water to drink to facilitate swallowing. The posterior approach is shown in Figure 6-12.

Although both the anterior and the posterior approaches of palpation are usually performed, the examiner can rarely feel the thyroid gland in its normal state.

The consistency of the gland should be evaluated. The normal thyroid gland has a consistency of muscle tissue. Unusual hardness is associated with cancer or scarring. Softness, or sponginess, is often observed with a toxic goiter. Tenderness of the thyroid gland is associated with acute infections or with hemorrhage into the gland.

If the thyroid is enlarged, it should also be examined by auscultation. The bell of the stethoscope is placed over the lobes of the thyroid while the examiner listens for the presence of a bruit (a murmur heard when there is increased turbulence in a vessel). The finding of a systolic or a to-and-fro2 thyroid bruit, particularly if heard over the superior pole, indicates an abnormally large blood flow and is highly suggestive of a toxic goiter.

Palpate for Supraclavicular Nodes

Palpation for supraclavicular nodes concludes the examination of the head and neck. The examiner stands behind the patient and places the fingers into the medial supraclavicular fossae, deep to the clavicle and adjacent to the sternocleidomastoid muscles. The patient is instructed to take a deep breath while the examiner presses deeply in and behind the clavicles. Any supraclavicular nodes that are enlarged are palpated as the patient inspires. This technique is shown in Figure 6-13.

The examination of the trachea is discussed in Chapter 10, The Chest. The examination of the carotid arterial and jugular venous pulsations is discussed in Chapter 11, The Heart.

Clinicopathologic Correlations

Although iodine deficiency is still a worldwide cause of thyroid enlargement, other important causes of goiter are infection, autoimmune disease, cancer, and isolated nodules. An enlarged thyroid may be associated with hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, or a simple or multinodular goiter of normal function.

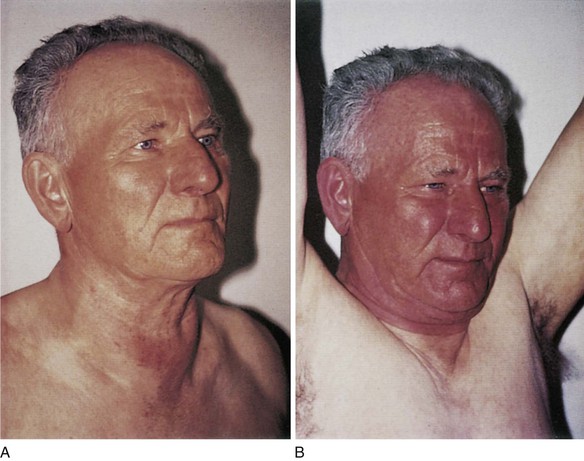

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, the thyroid may enlarge and expand into the chest cavity. If the thyroid is large enough, it may impair venous outflow from the head and neck and may even be responsible for airway or vascular compromise. Pemberton’s sign is useful for detecting latent obstruction in the thoracic inlet. To determine whether the sign is present, the patient is asked to elevate both arms until they touch the sides of the head. Pemberton’s sign is present when facial suffusion with dilatation of the cervical veins develops within a few seconds. After 1 to 2 minutes, the face may even become cyanotic. Figure 6-14 shows a patient with a positive Pemberton’s sign. The patient is a 62-year-old man with an anterior neck mass, the existence of which was known for 25 years. The upper border of the thyroid was palpable on examination, but the lower pole descended below the clavicle and was not palpable.

Figure 6–14 A and B, Pemberton’s sign.

As indicated in the quotation at the beginning of this chapter, hyperthyroidism may manifest with a variety of generalized symptoms and signs. It has been said, “To know thyroid disease is to know medicine,” because there are so many generalized effects of thyroid hormone excess. Table 6-1 lists the variety of clinical symptoms related to thyroid hormone excess.

Table 6–1

Symptoms of Hyperthyroidism

| Organ System | Symptom |

| General | Preference for the cold Weight loss with good appetite |

| Eyes | Prominence of eyeballs* Puffiness of eyelids Double vision Decreased motility |

| Neck | Goiter |

| Cardiac | Palpitations Peripheral edema† |

| Gastrointestinal | Increased numbers of bowel movements |

| Genitourinary | Polyuria Decreased fertility |

| Neuromuscular | Fatigue Weakness Tremulousness |

| Emotional | Nervousness Irritability |

| Dermatologic | Hair thinning Increased perspiration Change in skin texture Change in pigmentation |

* Appears to result from mucopolysaccharide deposition behind the orbit.

† Appears to result from excessive mucopolysaccharide deposition under the skin, especially in the legs.

A nervous, perspiring patient with a stare and bulging eyes offers an unmistakable combination of physical signs associated with hyperthyroidism. The most common type of hyperthyroidism is the diffuse toxic goiter, known as Graves’ disease. Symptomatic Graves’ disease has an incidence of 1 per 1000 women in multinational studies. This disease can occur at any age and in all races. Graves’ disease is viewed as an autoimmune disorder provoked by the elaboration of a thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin. The many clinical manifestations of Graves’ disease are truly multisystemic and include the following:

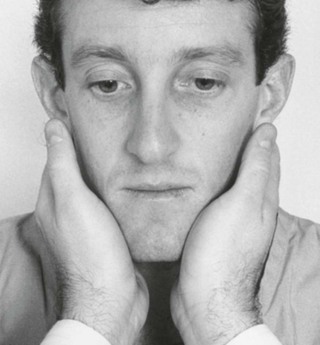

On occasion, Graves’ disease manifests with unilateral proptosis, as shown in Figure 6-15. This patient presented with proptosis and was treated for Graves’ disease 20 years before this photograph was taken. As is common, the proptosis never disappeared.

Figure 6–15 Graves’ disease: unilateral proptosis.

Sometimes hyperthyroidism is caused by a single hot nodule.3

Toxic adenomatous goiter, also known as Plummer’s disease, accounts for fewer than 10% of all cases of hyperthyroidism. Hyperthyroidism may be caused by a single, autonomously functioning thyroid adenoma. The adenoma is usually papillary and is unrelated to any autoimmune process. Hyperfunction may also occur in multiple nodules. The distinctive features of hyperthyroidism caused by Graves’ and Plummer’s diseases are summarized in Table 6-2.

Table 6–2

Distinctive Features of Graves’ Disease and Plummer’s Disease

| Feature | Graves’ Disease (Toxic Diffuse Goiter*) | Plummer’s Disease (Toxic Adenomatous Goiter†) |

| Age at onset | 40 years | 40 years |

| Onset | Acute | Insidious |

| Goiter | Diffuse | Nodular |

| Signs and symptoms | Clear-cut | Vague |

| Myopathy (muscle disease) | Present | Absent |

| Heart involvement | Sinus tachycardia Atrial fibrillation (occasional) |

Atrial fibrillation (frequent) Congestive heart failure |

| Ophthalmopathy | Exophthalmos Vision changes Motility abnormalities Chemosis (conjunctival edema)‡ |

Eyelid lag Eyelid retraction |

* See Figures 6-6 and 6-15.

† See Figure 6-7.

‡ See Figure 7-44.

Approximately 5% of the population has a single thyroid nodule larger than 1 cm in diameter. Although most (90% to 95%) of these nodules are benign and necessitate no therapy, all should be investigated for malignancy. They develop from thyroid follicular cells and can be found in normal-sized thyroid glands and goiters. The history and physical examination can provide some clues as to the nature of the lump. Table 6-3 summarizes some of the important characteristics of benign and malignant nodules.

Table 6–3

Characteristics of Benign and Malignant Thyroid Nodules

| Characteristic | Benign Nodule | Malignant Nodule |

| Age at onset | Adulthood | Adulthood |

| Predominant gender | Female | Male |

| Patient history | Symptoms present | Previous x-ray treatment to head or neck |

| Family history | Benign thyroid diseases | None |

| Speed of enlargement | Slow | Rapid |

| Change in voice | Absent | Present |

| Number of nodules | More than one | One |

| Lymph nodes | Absent | Present |

| Remainder of thyroid | Abnormal | Normal |

Many patients with thyroid cancer, especially in the early stages, do not experience any symptoms. As the cancer grows, symptoms may include a lump or nodule in the neck, hoarseness, difficulty in speaking, difficulty in swallowing, pain in the neck or throat, and swollen lymph nodes. Many symptoms and signs of thyroid disease have been evaluated for their sensitivity and specificity. Most of these findings are specific but are too insensitive to be useful. Table 6-4 summarizes the characteristics that are significant when a thyroid nodule is evaluated for malignancy. The most useful signs are a palpable, hard nodule and a fixed mass.

Table 6–4

Characteristics of Thyroid Nodules Suspect for Cancer

| Characteristic | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

| Palpable, hard nodule | 42 | 89 |

| Fixed mass | 31 | 94 |

| Local symptoms | 3 | 97 |

| Dysphagia | 10 | 93 |

| Unilateral adenopathy | 5 | 96 |

| Nodule found on routine examination | 50 | 56 |

| Family history of goiter | 17 | 79 |

Data from Kendall and Condon (1976) and Haff et al. (1976)

There are several types of thyroid cancer: papillary, follicular, medullary, and anaplastic. Papillary and follicular carcinomas are well differentiated and represent 80% to 90% of all thyroid cancers. Both types begin in the follicular cells of the thyroid. Papillary carcinomas are the most common (80% to 90% of all thyroid cancers). They typically grow very slowly. Usually they occur in only one lobe of the thyroid gland, but approximately 10% to 20% of the time both lobes are involved. Even though papillary thyroid cancer is slow growing, it often spreads early to the lymph nodes in the neck. Follicular cancer is much less common than papillary thyroid cancer, making up approximately 5% to 10% of all thyroid cancers. It tends to occur in older individuals, and it is more common in countries where people do not get enough iodine in their diet. If there is early detection, these cancers can be treated successfully. Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) accounts for only 5% to 10% of all thyroid cancers. MTC is the only thyroid cancer that develops from the C cells, not the follicular cells, of the thyroid gland. There are two types of MTC: sporadic and familial. On occasion, MTC is associated with tumors of certain other organs (adrenal and parathyroid gland) and is called multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN 2), of which there are two subtypes: MEN 2a is associated with pheochromocytomas and parathyroid gland tumors; MEN 2b lacks the parathyroid gland tumors. Genetic studies should be performed on individuals with MTC. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is the least common of all thyroid cancers, accounting for 1% to 2%. It is also, however, the most aggressive type and therefore is the most difficult to control and treat.

A heavy, puffy-faced, lethargic patient with dry skin, sparse hair, and a hoarse voice provides the classic picture of hypothyroidism. Hypothyroidism develops insidiously. Often the only complaint is a tired or “run-down” feeling. The careful interviewer and examiner must be on the alert with any patient, especially one older than 60 years, who has these symptoms. Patients with hypothyroidism commonly have hung, or delayed, reflexes. Measurement of the relaxation time of the Achilles tendon reflex has long been used to monitor the effects of treatment in patients with hypothyroidism. However, it is useless as a screening technique because there may be many false-negative or false-positive results.

Table 6-5 lists some of the major symptoms and signs of hypothyroidism.

Table 6–5

Symptoms and Signs of Hypothyroidism

| System | Symptom | Sign |

| General | Weight gain with regular diet Feeling chilly while other people are warm |

Obesity |

| Gastrointestinal | Constipation | Enlarged tongue |

| Cardiovascular | Fatigue | Hypotension Bradycardia |

| Nervous | Speech disorders Short attention span Tremor |

Hyporeflexia Defective abstract reasoning Spasticity Tremor Depressed affect |

| Musculoskeletal | Lethargy Thickened, dry skin Hair loss Brittle nails Leg cramps Puffy eyelids Puffy cheeks |

Hypotonia Puffy facies |

| Reproductive | Heavier menses Decreased fertility |

The bibliography for this chapter is available at studentconsult.com.

Bibliography

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures. [Atlanta] 2011.

Bahn RS, et al. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Thyroid. 2011;21:593.

Davies TF, Larsen PR. Thyrotoxicosis. Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. ed 11. Saunders Elsevier: Philadelphia; 2008.

Haff RC, et al. Factors increasing the probability of malignancy in thyroid nodules. Am J Surg. 1976;131:707.

Kendall LW, Condon RE. Prediction of malignancy in solitary thyroid nodules. Lancet. 1976;1:1019.

King AD. Multimodality imaging of head and neck cancer. Cancer Imaging. 2007;7(Spec No A):S37.

Mohan PS, et al. Thyroglossal duct cyst: a consideration in adults. Am Surg. 2005;71:508.

PubMed Health. Graves’ disease. [Updated June 4, 2012. Available at] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0001398/; 2013 [Accessed February 5] .

PubMed Health. Hyperthyroidism. [Updated June 4, 2012. Available at] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0001396/; 2013 [Accessed February 5] .

Rosenberg TL, Brown JJ, Jefferson GD. Evaluating the adult patient with a neck mass. Med Clinic North Am. 2010;94:1017.

Stan MN, et al. The evaluation and treatment of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Med Clin North Am. 2012;96:311.

Wallace C, Siminoski K. The Pemberton sign. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:568.

Werner JA. Patterns of metastasis in head and neck cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2007;135:203.

1 A thyroglossal cyst may arise anywhere along the route of the thyroid gland’s descent from the foramen cecum of the tongue to its adult location in the neck. See Figure 21-42. The thyroid gland is a painless, mobile structure that moves on swallowing and with movement of the tongue.

2 Refers to two separate murmurs, systolic and diastolic.

3 The terms hot and cold are descriptions of nodules seen on a thyroid scan and are used to indicate whether a nodule accumulates more or less radioactive iodine than the surrounding thyroid tissue. A hot nodule is functioning thyroid tissue and has a greater iodine uptake than the surrounding tissue. A cold nodule is nonfunctioning and fails to take up the radioactive tracer.