Chapter 8 The haematological system

The haematological history

Presenting symptoms (Table 8.1)

Patients with anaemia may present with weakness, tiredness, dyspnoea, fatigue or postural dizziness. Anaemia due to iron deficiency is often the result of gastrointestinal blood loss, or sometimes recurrent heavy menstrual blood loss, and so these symptoms should be sought. Disorders of platelet function or blood clotting may present with easy-bruising or bleeding problems. Recurrent infection may be the first symptom of a disorder of the immune system, including leukaemia or HIV infection. The patient may have noticed lymph node enlargement, which can occur with lymphoma or leukaemia. Not all lumps are lymph nodes; consider the differential diagnosis (Table 8.2). Ask about fever, its duration and pattern. Lymphomas can be a cause of chronic fever, and viral infections such as cytomegalovirus and infectious mononucleosis are associated with haematological abnormalities and fever.

| Major symptoms |

| Symptoms of anaemia: weakness, tiredness, dyspnoea, fatigue, postural dizziness |

| Bleeding (menstrual, gastrointestinal, after dental extractions) |

| Easy bruising, purpura, thrombotic tendency |

| Lymph gland enlargement |

| Bone pain |

| Infection, fever or jaundice |

| Enlargement of the tongue from amyloidosis |

| Paraesthesiae (e.g. B12 deficiency) |

| Skin rash |

| Weight loss |

TABLE 8.2 Differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy

| 1 Lipoma—usually large and soft; may not be in lymph node area |

| 2 Abscess—tender and erythematous, may be fluctuant |

| 3 Sebaceous cyst—intradermal location |

| 4 Thyroid nodule—forms part of thyroid gland |

| 5 Secondary to recent immunisation |

Past history

A history of gastric surgery or malabsorption may give a clue regarding the underlying cause of an anaemia. Anaemia in patients with systemic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis or uraemia can be multifactorial. Previous blood transfusions may have been required to treat the anaemia. On the other hand, patients with polycythaemia may have had many venesections (page 236).

Family history

There may be a history of thalassaemia or sickle cell anaemia in the family. Haemophilia is a sex-linked recessive disease while von Willebrand’s diseasea is autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance (Table 8.3).

| Trauma |

| Thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction (Table 8.4) |

The haematological examination

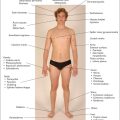

Examination anatomy

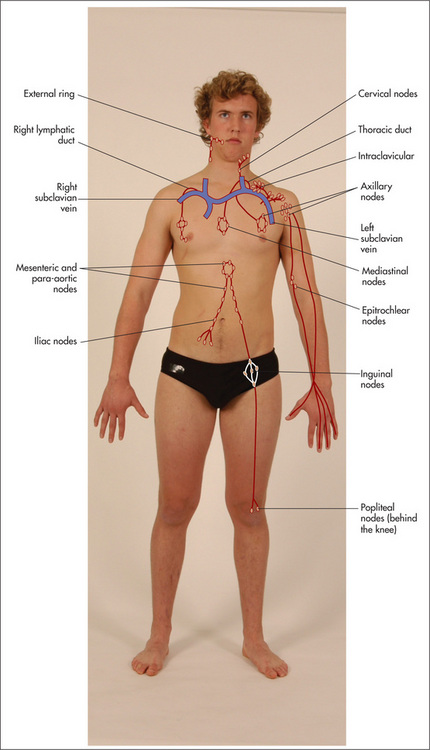

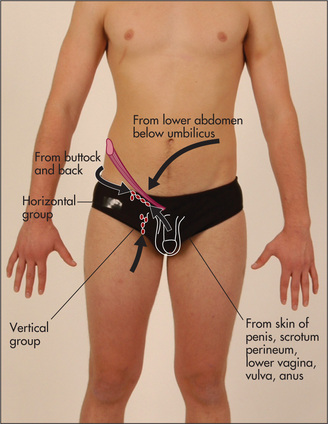

An important part of the examination involves assessment of all the palpable groups of lymph nodes. As each group is examined its usual drainage area must be kept in mind (Figure 8.1). It follows that whenever an abnormality is discovered anywhere that might be due to infection or malignancy its draining lymph nodes must be examined.

General appearance

Position the patient as for the gastrointestinal examination—lying on the bed with one pillow. Look for signs of wasting and for pallor (which may be an indication of anaemia—Good signs guide 3.1, page 26). 1–3 Note the patient’s racial origin (e.g. thalassaemia). If there is any bruising, look at its distribution and extent. Jaundice may be present and can indicate haemolytic anaemia. Scratch marks (following pruritus, which sometimes occurs with lymphoma and myeloproliferative disease) should be noted.

The hands

The detailed examination begins in the usual way with assessment of the hands. Look at the nails for koilonychia—these are dry, brittle, ridged, spoon-shaped nails, which are rarely seen today. They can be due to severe iron deficiency anaemia, although the mechanism is unknown. Occasionally koilonychia may be due to fungal infection. They may also be seen in Raynaud’s phenomenon. Digital infarction (Figure 8.2) may be a sign of abnormal globulins (e.g. cryoglobulinaemia). Pallor of the nail beds may occur in anaemia but is an unreliable sign. Pallor of the palmar creases suggests that the haemoglobin level is less than 70 g/L, but this is also a rather unreliable sign.1

Note any changes of rheumatoid or gouty arthritis, or connective tissue disease (Chapter 9). Rheumatoid arthritis, when associated with splenomegaly and neutropenia, is called Felty’s syndromeb: the mechanism of the neutropenia is unknown, but it can result in severe infection. Felty’s syndrome can also be associated with thrombocytopenia (Figure 8.3), haemolytic anaemia, skin pigmentation and leg ulceration. Gouty tophi and arthropathy may be present in the hands. Gout may be a manifestation of a myeloproliferative disease. Connective tissue diseases can cause anaemia because of the associated chronic inflammation.

Now take the pulse. A tachycardia may be present. Anaemic patients have an increased cardiac output and compensating tachycardia because of the reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of their blood.

Look for purpura (Figure 8.3), which is really any sort of bruising, due to haemorrhage into the skin. The lesions can vary in size from pinheads called petechiae (from Latin petechia ‘a spot’) (Table 8.4) to large bruises called ecchymoses (Table 8.3).

* Eduard Henoch (1820–1910), professor of paediatrics, Berlin, described this in 1865, and Johannes Schönlein (1793–1864), Berlin physician, described it in 1868.

The forearms

If thrombocytopenia or capillary fragility is suspected, the Hess testc can be performed.d

Epitrochlear nodes

These must always be palpated. The best method is to flex the patient’s elbow to 90 degrees, abduct the upper arm a little and then place the palm of the right hand under the patient’s right elbow (Figure 8.4). The examiner’s thumb can then be placed over the appropriate area, which is proximal and slightly anterior to the medial epicondyle. This is repeated with the left hand for the other side. An enlarged epitrochlear node is usually pathological. It occurs with local infection, non-Hodgkin’s lymphomae or rarely syphilis. Note the features and different causes as listed in tables 8.5 and 8.6. Certain symptoms and signs suggest that lymphadenopathy may be the result of a significant disease (Good signs guide 8.1).

| During the palpation of lymph nodes the following features must be considered: |

| Site |

TABLE 8.6 Causes of localised lymphadenopathy

| 1 Inguinal nodes; infection of lower limb, sexually transmitted disease, abdominal or pelvic malignancy; immunisations |

| 2 Axillary nodes; infections of the upper limb, carcinoma of the breast, disseminated malignancy; immunisations |

| 3 Epitrochlear nodes; infection of the arm, lymphoma, sarcoidosis |

| 4 Left supraclavicular nodes; metastatic malignancy from the chest, abdomen (especially stomach—Troiser’s sign) or pelvis |

| 5 Right supraclavicular nodes; malignancy from the chest or oesophagus |

GOOD SIGNS GUIDE 8.1 Factors suggesting lymphadenopathy is associated with significant disease

| LR if present | LR if absent | |

| Age > 40 | 2.4 | 0.4 |

| Weight loss | 3.4 | 0.8 |

| Fever | NS | NS |

| Head and neck but not supraclavicular | NS | NS |

| Supraclavicular | 3.2 | 0.8 |

| Axillary | 0.8 | NS |

| Inguinal | 0.6 | NS |

| Size: | ||

| < 4 cm2 | 0.4 | — |

| 4–9 cm2 | NS | — |

| > 9 cm2 | 8.4 | — |

| Hard texture | 3.3 | NS |

| Tender | 0.4 | 1.3 |

| Fixed node | 10.9 | NS |

| 3 or fewer nodes | 0.04 | — |

| 5 or 6 nodes | 5.1 | — |

| 7 or more nodes | 21.9 | — |

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

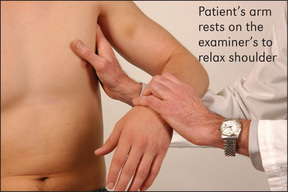

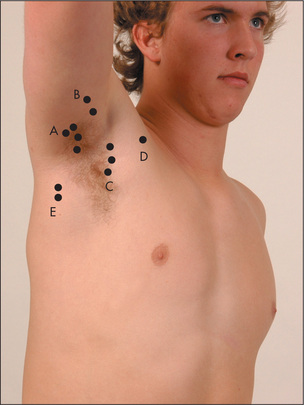

Axillary nodes

To palpate these, the examiner raises the patient’s arm and, using the left hand for the right side, pushes his or her fingers as high as possible into the axilla. The patient’s arm is then brought down to rest on the examiner’s forearm. The opposite is done for the other side (Figure 8.5).

There are five main groups of axillary nodes: (i) central; (ii) lateral (above and lateral); (iii) pectoral (medial); (iv) infraclavicular; and (v) subscapular (most inferior) (Figure 8.6). An effort should be made to feel for nodes in each of these areas of the axilla.

The face

The eyes should be examined for the presence of scleral jaundice, haemorrhage or injection (due to increased prominence of scleral blood vessels, as in polycythaemia). Conjunctival pallor suggests anaemia and is more reliable than examination of the nail beds or palmar creases.3 In northern Europeans the combination of prematurely grey hair and blue eyes may indicate a predisposition to the autoimmune disease pernicious anaemia, where there is a vitamin B12 deficiency due to lack of intrinsic factor secretion by an atrophic gastric mucosa.

The mouth should be examined for hypertrophy of the gums, which may occur with infiltration by leukaemic cells, especially in acute monocytic leukaemia, or with swelling in scurvy. Gum bleeding must also be looked for, and ulceration, infection and haemorrhage of the buccal and pharyngeal mucosa noted. Atrophic glossitis occurs with megaloblastic anaemia or iron deficiency anaemia. Multiple telangiectasiae may appear around the mouth or in the mouth in patients with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Look to see if the tonsils are enlarged. Waldeyer’s ringf is a circle of lymphatic tissue in the posterior part of the oropharynx and nasopharynx, and includes the tonsils and adenoids. Sometimes non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma will involve Waldeyer’s tonsillar ring, but Hodgkin’s disease rarely does.

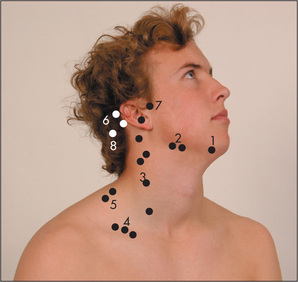

Cervical and supraclavicular nodes

Sit the patient up and examine the cervical nodes from behind. There are eight groups. Attempt to identify each of the groups of nodes with your fingers (Figure 8.7). First palpate the submental node, which lies directly under the chin, and then the submandibular nodes, which are below the angle of the jaw. Next palpate the jugular chain, which lies anterior to the sternomastoid muscle, and then the posterior triangle nodes, which are posterior to the sternomastoid muscle. Palpate the occipital region for occipital nodes and then move to the postauricular node behind the ear and the preauricular node in front of the ear. Finally from the front, with the patient’s shoulders slightly shrugged, feel in the supraclavicular fossa and at the base of the sternocleidomastoid muscle for the supraclavicular nodes. Causes of lymphadenopathy, localised and generalised, are given in Table 8.7. Note that small cervical nodes are often palpable in normal young people.4,5

| Generalised lymphadenopathy |

The detection of lymphadenopathy should lead to a search of the area drained by the enlarged nodes. This may reveal the likely cause (see Table 8.6).

The abdominal examination

Lay the patient flat again. Examine the abdomen carefully, especially for splenomegaly6 (Table 8.8, Good signs guide 8.2), hepatomegaly, para-aortic nodes (rarely palpable), inguinal nodes and testicular masses. Remember that a central deep abdominal mass may occasionally be due to enlarged para-aortic nodes. Para-aortic adenopathy strongly suggests lymphoma or lymphatic leukaemia. The rectal examination may reveal evidence of bleeding or a carcinoma.

| Massive |

Note: Secondary carcinomatosis is a very rare cause of splenomegaly.

* Phillipe Charles Ernest Gaucher (1854–1918), who described this in 1882, was physician and dermatologist at the Hôpital St-Louis, Paris.

GOOD SIGNS GUIDE 8.2 Splenomegaly

| Finding | Positive LR | Negative LR |

| Spleen palpable | 8.5 | 0.5 |

| Spleen percussion positive | 1.7 | 0.7 |

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

Assessment of the patient with suspected malignancy is presented in Table 8.9.7

TABLE 8.9 Assessing the patient with suspected malignancy

| 1 Palpate all draining lymph nodes |

| 2 Examine all remaining lymph node groups |

| 3 Examine the abdomen, particularly for hepatomegaly and ascites |

| 4 Feel the testes |

| 5 Perform a rectal examination and pelvic examination |

| 6 Examine the lungs |

| 7 Examine the breasts |

| 8 Examine all the skin and nails for melanoma |

Inguinal nodes

There are two groups—one along the inguinal ligament and the other along the femoral vessels. Small, firm mobile nodes are commonly found in otherwise normal subjects (Figure 8.8).

The legs

Inspect for any bruising, pigmentation or scratch marks. Palpable purpura over the buttocks and legs are present in Henoch-Schönlein purpurag (Figure 8.9). Leg ulcers may occur above the medial or lateral malleolus in association with haemolytic anaemia (including sickle cell anaemia and hereditary spherocytosis), probably as a result of tissue infarction due to abnormal blood viscosity. Leg ulcers can also occur with thalassaemia, macroglobulinaemia, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and polycythaemia, as well as in Felty’s syndrome. Chronic use of hydroxyurea for myeloproliferative disorders can cause malar ulcers.

Figure 8.9 Henoch-Schönlein purpura

From McDonald FS, ed., Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine, with permission. © Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press.

Very occasionally, popliteal nodes may be felt in the popliteal fossa.

The legs should also be examined for evidence of the neurological abnormalities caused by vitamin B12 deficiency: peripheral neuropathy and subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord. Vitamin B12 is an essential cofactor in the conversion of homocysteine to methionine; in B12 deficiency, the lack of methionine impairs methylation of myelin basic protein. Deficiency of vitamin B12 can also result in optic atrophy and mental changes. Lead poisoning causes anaemia and foot (or wrist) drop.

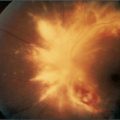

The fundi

Examine the fundi. An increase in blood viscosity, which occurs in diseases such as macroglobu, myeloproliferative disease or chronic granulocytic leukaemia, can cause engorged retinal vessels and later papilloedema. Haemo may occur because of a haemostatic disorder. Retinal lesions (multiple yellow-white patches) may be present in toxoplasmosis (see Figure 16.5) and cytomegalovirus infections (see Figure 16.6).

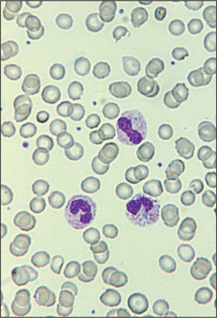

Examination of the peripheral blood film

This is a simple and useful clinical investigation.

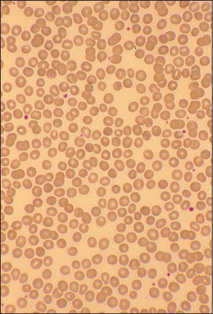

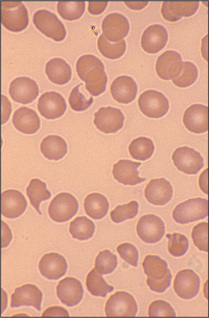

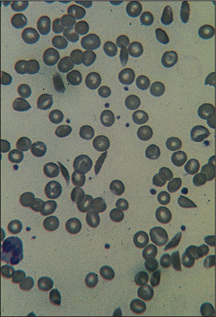

A properly made peripheral blood film is one of the simplest, least invasive and most readily accessible forms of ‘tissue biopsy’, and can be a very useful diagnostic tool in clinical medicine. An examination of the patient’s blood film can (i) assess whether the morphology of red cells, white cells and platelets is normal; (ii) help to characterise the type of anaemia; (iii) detect the presence of abnormal cells and provide clues about quantitative changes in plasma proteins—e.g. paraproteinaemia; and (iv) help to make the diagnosis of an underlying infection, malignant infiltration of the bone marrow or primary proliferative haematological disorder. The following pages present illustrated examples of some clinical problems diagnosed by examination of the blood film (Figures 8.10 to 8.22).

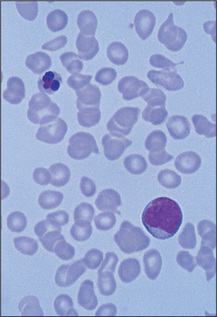

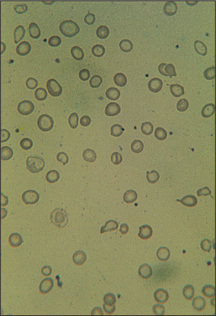

Figure 8.10 Iron-deficiency anaemia

Red cells show varying shape and size and are generally hypochromic.

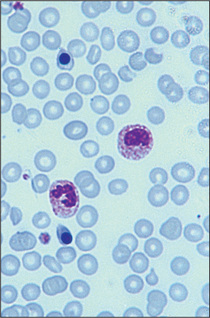

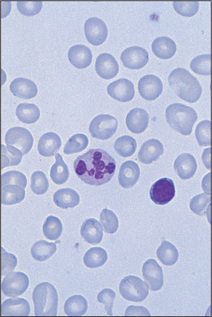

Figure 8.11 Megaloblastic anaemia

Red cells are macrocytic with many oval forms and the neutrophil is hypersegmented.

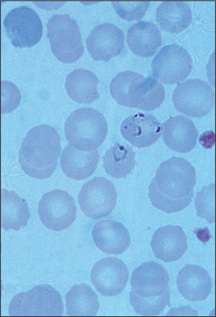

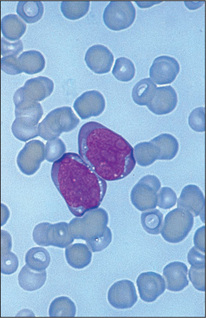

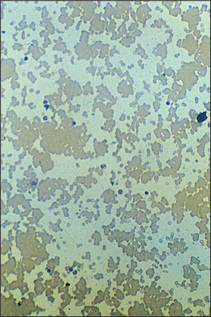

Figure 8.13 Autoagglutination

Cold haemagglutinin disease. Film shows clumping of red cells (low power).

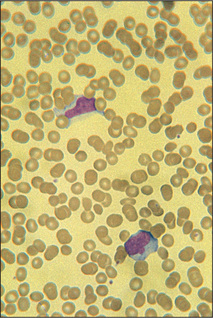

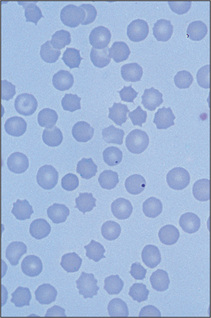

Figure 8.18 Postsplenectomy picture

Film shows several Howell-Jolly bodies, target cells and crenated cells.

Correlation of physical signs and haematological disease

Anaemia

Anaemia is a reduction in the concentration of haemoglobin below 135 g/L in an adult man and 115 g/L in an adult woman. Anaemia is not a disease itself but results from an underlying pathological process (Table 8.10, page 235). It can be classified according to the blood film. Red blood cells with a low mean cell volume (MCV) appear small (microcytic) and pale (hypochromic). Those with a high MCV appear large and round or oval-shaped (macrocytic). Alternatively, the red blood cells may be normal in shape and size (normochromic, normocytic) but reduced in number.

Signs of a severe anaemia of any cause include pallor, tachycardia, wide pulse pressure, systolic ejection murmurs due to a compensatory rise in cardiac output, and cardiac failure if myocardial reserve is reduced. There may be signs of the underlying cause.

Pancytopenia

Acute leukaemia

Signs of infiltration of the haemopoietic system

These include: (i) bony tenderness, due to infiltra or infarction; (ii) lymphadenopathy (slight to moderate, especially in acute lymphoblastic leuka); (iii) splenomegaly (slight to moderate, occurs especially in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; the spleen may be tender due to splenic infarction); and (iv) hepatomegaly (slight to moderate).

Chronic leukaemia

Signs of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

There may be tiredness and pallor. Recurrent acute infections occur.

Other abnormalities may include a Coombs’h test—positive haemolytic anaemia, herpes zoster skin infections and nodular infiltrates. Patients may note a hypersensitivity to insect bites before the diagnosis is made.

Myeloproliferative disease

Polycythaemia

This is an elevated haemoglobin concentration and can result from an increased red blood cell mass or a decreased plasma volume. Polycythaemia rubra vera results from an autonomous increase in the red blood cell production. Patients with polycythaemia often have a striking ruddy, plethoric appearance. To examine a patient with suspected polycythaemia, assess for both the manifestations of polycythaemia rubra vera and for other possible underlying causes of polycythaemia (Table 8.11).

| Signs of polycythaemia rubra vera |

* Felix Gaisböck (1868–1955), German physician, described this in 1905.

Look at the patient and estimate the state of hydration (dehydration alone can cause an elevated haemoglobin due to haemoconcentration). Note if there is a Cushingoid (page 309) or virilised (page 315) appearance. Cyanosis may be present because of an underlying condition such as cyanotic congenital heart disease or chronic lung disease. Look for nicotine staining (smoking). All these diseases can result in secondary polycythaemia.

The legs must be inspected for scratch marks, gouty tophi (Figure 9.57, page 282) and arthropathy, as well as for signs of peripheral vascular disease. In polycythaemia rubra vera, secondary gout occurs due to the increased cellular turnover resulting in hyperuricaemia. Peripheral vascular disease occurs in polycythaemia rubra vera because of thrombosis (as there is increased platelet adhesiveness and accelerated atherosclerosis) and slowed circulation due to hyperviscosity.

Primary myelofibrosis

Essential thrombocythaemia

This is a sustained elevation of the platelet count above normal without any primary cause.

Lymphoma (Figure 8.23)

This is a malignant disease of the lymphoid system. There are two main clinicopathological types: Hodgkin’s disease (with the characteristic Reed-Sternberg celli) and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Signs of lymphoma depend on the stages of the disease (Table 8.12).

| Stage I |

| Disease confined to a single lymph node region or a single extralymphatic site (IE) |

| Stage II |

| Disease confined to two or more lymph node regions on one side of the diaphragm |

| Stage III |

| Disease confined to lymph nodes on both sides of the diaphragm with or without localised involvement of the spleen (IIIS), other extralymphatic organ or site (IIIE), or both (IIIES) |

| Stage IV |

| Diffuse disease of one or more extralymphatic organs (with or without lymph node disease) |

| For any stage: a = no symptoms; b = fever, weight loss greater than 10% in 6 months, night sweats. |

| E involves direct invasion from lymph node into surrounding tissue. |

Signs of Hodgkin’s disease

Multiple myeloma

Summary

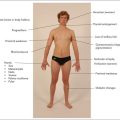

The haematological examination: a suggested method (Figure 8.24)

Figure 8.24 Haematological system examination

Go to the axillae and palpate the axillary nodes. There are five main areas: central, lateral (above and lateral), pectoral (most medial), infraclavicular and subscapular (most inferior).

Sit the patient up. Examine the cervical nodes from behind. There are eight groups: submental, submandibular, jugular chain, supraclavicular, posterior triangle, postauricular, preauricular and occipital. Then feel the supraclavicular area from the front. Tap the spine with your fist for bony tenderness (caused by an enlarging marrow—e.g. in myeloma or carcinoma). Also gently press the sternum, clavicles and shoulders for bony tenderness.

Finally, examine the fundi, look at the tempera chart, and test the urine.

1. Strobach RS, Anderson SK, Doll DC, Ringenberg QS. The value of the physical examination in the diagnosis of anaemia: correlation of the physical findings and the haemoglobin concentrations. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:831-832. Palmar crease pallor can occur above a haemoglobin of 70 g/L

2. Nardone DA, Roth KM, Mazur DJ, McAfee JH. Usefulness of physical examination in detecting the presence or absence of anemia. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:201-204.

3. Sheth TN, Choudray NK, Bowes M, Detsky AS. The relation of conjunctival pallor to the presence of anemia. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:102-106. The presence of conjunctival pallor is a useful indicator of anaemia, but its absence is unhelpful. It is also a reliable sign

4. Linet OI, Metzler C. Practical ENT: incidence of palpable cervical nodes in adults. Postgrad Med. 1977;62:210-211. 213 In young adults without chronic disease, palpable cervical lymph nodes are often detected but are not clinically important. Remember, posterior cervical nodes are almost never normal

5. Robertson TI. Clinical diagnosis in patients with lymphadenopathy. Med J Aust. 1979;2:73-76.

6. Grover SA, Barkun AN, Sackett DL. Does this patient have splenomegaly? JAMA. 1993;270:2218-2221. A valuable guide to assessment of splenomegaly, although the recommendations are controversial. A combination of percussion and palpation may best identify splenomegaly, but in contrast to hepatomegaly, percussion may be modestly more sensitive, according to the few available studies. Our conclusion is that this needs to be better established; in practice splenomegaly is often missed by percussion alone

7. Anonymous. Cancer detection in adults by physical examination. US Public Health Service. Am Fam Phys. 1995;51:871-874. 877–880, 883–885

a EA von Willebrand (1870–1949), Swedish physician, described this in 1926.

b Augustus Roi Felty (1895–1963), physician, Hartford Hospital, Connecticut, described this in 1924.

c Alfred Hess (1875–1933), professor of paediatrics, New York, described this in 1914.

d This test is only of historical interest these days, as a platelet count can be obtained almost as quickly in most hospitals and clinics. A blood pressure cuff, placed over the upper arm, is inflated to a point 10 mmHg above the diastolic blood pressure. Wait for 5 minutes, then deflate the cuff and wait for another 5 minutes before inspecting the arm. Look for petechiae, which are usually most prominent in the cubital fossa and near the wrist, where the skin is most lax. Fewer than 5 petechiae per cm2 is normal, while more than 20 is definitely abnormal, suggesting thrombocytopenia, abnormal platelet function or capillary fragility.

e Thomas Hodgkin (1798–1866), famous student at Guy’s Hospital, London, described his disease in 1832. The first case he described was a patient of Richard Bright’s. Hodgkin was one of the first to use the stethoscope in England. On failing to be appointed a physician, he gave up medicine and became a missionary.

f Heinrich Wilhelm Gottfried von Waldeyer-Hartz (1836–1921), Berlin anatomist.

g Henoch-Schönlein purpura is also characterised by glomerulonephritis (manifested by haematuria and proteinuria), arthralgias and abdominal pain.

h Robin Coombs (b. 1921), Quick professor of biology, Cambridge.

i Dorothy Reed (1874–1964), pathologist at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, described these cells in 1906 and Karl Sternberg (1872–1935), pathologist, described giant cells in 1898.