Chapter 22

The Geriatric Patient

Old age isn’t so bad when you consider the alternative.

Maurice Chevalier (1888–1972)

General Considerations

The geriatric patient is an individual 65 years of age or older. Among such individuals, there is considerable variation in general health, mental status, functional ability, personal and social resources, marital status, living arrangements, creativity, and social integration. The age range of this rapidly growing population spans more than 40 years. The world’s geriatric population is currently increasing at a rate of 2.5% per year—significantly faster than the total population. Between 1900 and 2000, the number of Americans older than 65 years increased from a little more than 3 million to 35 million. Since 1960, the geriatric population has grown 107%, in comparison with 50% for the U.S. population as a whole. From 2000 to 2040, in the United States, the number of people 65 years of age or older is projected to increase from 34.8 million to 77.2 million. It is estimated that in the developed nations of the world, there are 146 million people 65 years of age and older. This group will increase to 232 million by the year 2020.

A decreasing rate of mortality, especially from heart disease and stroke, and a reduction in risk factors such as smoking, high blood pressure, and high serum cholesterol levels have contributed to this increased survival.

The population older than 85 years of age represents the fastest-growing segment of the U.S. population. This “graying of America” is expected to continue. By the year 2020, one fifth of the population will be older than 65 years of age. These statistics are extremely important in view of the cost of medical care for this population. Currently, 32% of all health care dollars is spent on the geriatric population, which constitutes only 12% of the total population.

Some other statistics are important. Eighty-nine percent of older adults are white. Older adult women outnumber older men 1.5 : 1 overall and 3 : 1 among individuals 95 years of age and older. African Americans constitute 12% of the total U.S. population but only 8% of the older age groups. In 1986, most older men (77%) were married, whereas most older women (52%) were widows. Fifteen percent of older men live alone, in comparison with 40% of women. Nursing home residents account for 5% of the population older than 65 years. Approximately 12% of the population older than 65 years of age continue to work; 25% are self-employed, in comparison with 10% of the total population. Five percent of the geriatric population—nearly 1 million individuals—are victimized by abuse or neglect. The U.S. Bureau of the Census estimates that 1 million Americans will be 100 years of age or older by the year 2050 and that nearly 2 million will be that age by the year 2080.

Falls are the leading cause of death from injury in individuals 65 years of age and older. Two thirds of reported injury-related deaths in patients 85 years of age and older are caused by falls. Falls are a leading cause of traumatic brain injuries. Approximately 3% to 5% of falls in older adults cause fractures. On the basis of the 2000 census, this translates to 360,000 to 480,000 fall-related fractures each year. Of all fall-related fractures, hip fractures cause the greatest number of deaths and lead to the most severe health problems and reductions in quality of life. In 1991, Medicare costs for hip fractures were estimated to be $2.9 billion. A fear of falling is also common; 50% to 60% of all patients older than 65 years of age have this fear.

Structure and Physiologic Characteristics

This section covers some of the anatomic and physiologic changes attributed to aging, as well as some of the physical findings that result.

Skin

There is atrophy of the epidermis, hair follicles, and sweat glands, which results in thinning skin. The skin becomes fragile and discolored. Wrinkling and dryness result from reduced skin turgor. In addition, the nails become thin and brittle, with marked ridging. There is decreased vascularity of the dermis, which contributes to prolonged healing time. There are common pigmentary changes, such as the development of senile lentigines, or “liver spots.” These brown macules are commonly found on the backs of the hands, forearms, and face. They are caused by localized mild epidermal hyperplasia, in association with increased numbers of melanocytes and increased melanin production. Figure 22-1 shows senile lentigines on the hand of an 87-year-old woman.

Figure 22–1 Senile lentigines in an 87-year-old woman. Notice the well-demarcated, brownish-black macules.

Another common skin change is senile (solar) keratosis, which is a well-defined, raised papule or plaque of epidermal hyperkeratosis. The surface scale varies in color from yellow to brown. These lesions are common on the face, neck, trunk, and hands. Figure 22-2 shows several senile keratoses on an 82-year-old man.

There is commonly a degeneration of the elastic fibers and collagen of the skin, resulting in a loss of elasticity and the development of senile purpura. These purple macules, commonly seen on the backs of the hands or on the forearms, result from blood that has extravasated through capillaries that have lost their elastic support. Figure 22-3 shows senile purpura on the forearm of a 90-year-old woman.

Figure 22–3 Senile purpura on the forearm of a 90-year-old woman. Note the red macules and the loss of turgidity of the skin.

Sebaceous gland hyperplasia, especially on the forehead and nose, is common. These yellowish glands range in size from 1 to 3 mm and have a central pore. It is important to differentiate these benign lesions from basal cell carcinomas.

Hair loses its pigment, which commonly results in “graying” of the hair. With the reduction in the number of hair follicles, there is hair loss all over the body: head, axilla, pubic area, and extremities. With the reduction in estrogens, an increase in hair may actually develop in many older women, especially on the chin and upper lip. Chin hairs on a 79-year-old woman are shown in Figure 22-4.

Figure 22–4 Chin hairs on a 79-year-old woman.

As a result of the reduction in subcutaneous tissue, there is less insulation and less padding over bony surfaces. This predisposes older people to hypothermia and the development of pressure sores, or decubitus ulcers. Figure 22-5 shows a pressure sore that developed on an 85-year-old man within 1 week. The man had been seen 1 week earlier when a small, intact erythematous area was noticed over his sacral area. He was brought back to the emergency department 7 days later with the decubitus ulcer seen in the figure. The ulceration eroded through the skin and muscle, into the sacrum, and into the bowel, with the development of a rectovesicular fistula.

Eyes

As a result of a reduction of orbital fat, the eyes appear sunken. Laxity of the eyelids, or senile ptosis, often develops. Entropion (see Fig. 7-19) or ectropion (see Fig. 7-20) may develop, caused by the lower eyelid’s falling inward or falling away, respectively. There may also be a clogging of the lacrimal duct, resulting in epiphora, or tearing. Fatty deposits in the cornea may produce an arcus senilis, seen in Figures 7-57 and 7-58. Inadequate production of mucous tears by the conjunctiva may predispose persons to corneal ulcers, exposure keratitis, or dry eye syndrome (see Chapter 7, The Eye).

An accumulation of yellow pigment in the lens alters color perception. A loss of elasticity in the lens results in presbyopia. Nuclear sclerosis of the lens develops into cataract formation. Patients experience a decrease in visual acuity and commonly complain of sensitivity to glare from interior lights, sunlight, or reflection from floors.

Degenerative changes in the iris, vitreous humor, and retina may impair visual acuity, reduce the fields of vision, and lead to the development of floaters (muscae volitantes). Senile macular degeneration (see Figs. 7-125 to 7-127) and retinal hemorrhages are other medically significant causes of decreases in visual acuity.

Ears

Degeneration of the organ of Corti may result in presbycusis, an impaired sensitivity to high-frequency tones. Patients experience a slowly progressive hearing loss with a consistent pattern of pure tone loss. Otosclerosis may produce conductive deafness, as does the excessive cerumen accumulation so commonly seen in older individuals. A degeneration of the hair cells in the semicircular canals may produce vertigo.

Nose and Throat

Atrophic changes occur in the mucosa of the nose and throat. Taste and especially smell may be altered, particularly in institutionalized individuals. A decrease in mucous production predisposes older patients to upper respiratory infections. A loss of elasticity in the laryngeal muscles may produce tremulousness and high pitch of the voice.

Mouth

Loss of teeth from dental caries or periodontal disease is common. Gingival recession may produce problems with dentures and a malalignment of bite. Atrophic changes in the salivary glands cause dryness of the mouth, known as xerostomia, a common complaint among older adults.

Lungs

A loss of elasticity in the pulmonary septa and atrophy of the alveoli cause a coalescence of the alveoli, with a reduction in vital capacity and oxygen diffusion. There are decreases in forced vital capacity and expiratory flow rate. A degeneration of bronchial epithelium and mucous glands increases the susceptibility to infections. Skeletal changes also contribute to a decrease in vital capacity.

Cardiovascular System

A loss of elasticity of the aorta may cause aortic dilation. The semilunar and atrioventricular valves may degenerate and become regurgitant. Alternatively, these valves may become sclerotic, which causes stenosis of the valves. Degeneration or calcification of the conducting system may cause heart block or arrhythmias.

Noncompliance of the peripheral arteries may cause hypertension with a widened pulse pressure. Systolic blood pressure rises progressively with age, whereas diastolic pressure levels off in the sixth decade of life; these developments lead to an increased prevalence of isolated systolic hypertension. Coronary atherosclerosis may produce angina, myocardial infarction, or nonspecific symptoms such as confusion or tiredness.

There are also decreases in plasma volume, ventricular filling time, and baroreflex sensitivity.

Breasts

The amount of glandular tissue decreases, and the tissue is replaced by fatty deposits. As a result of a loss of elastic tissue, the breasts become pendulous, and the ducts may be more palpable.

In men, gynecomastia may result from a change in the metabolism of sex hormones by the liver (see Fig. 13-21).

Gastrointestinal System

Atrophy of the gastrointestinal mucosa occurs with a reduction in the number of stomach and intestinal glands, causing alterations in secretion, motility, and absorption. Changes in elastic tissue and colonic pressures may result in diverticulosis, which can lead to diverticulitis. Pancreatic acinar atrophy is common, as are decreases in hepatic mass, hepatic blood flow, and microsomal enzyme activity. These decreases result in an increased half-life of lipid-soluble drugs.

Genitourinary System

There is a decrease in the number of glomeruli and a thickening of the basement membrane in Bowman’s capsule, resulting in a reduction in renal function. Degenerative changes occur in the renal tubules, which themselves are reduced in number. Renal blood flow is reduced to half by 75 years of age. Vascular changes may also contribute to a reduced glomerular filtration rate.

In men, prostatic atrophy or prostatic hypertrophy develops. Benign prostatic hypertrophy is present in 80% of all men older than 80 years. The penis decreases in size, and the testicles hang lower in the scrotum.

In postmenopausal women, the reduction in estrogen is associated with an increase in susceptibility to osteoporosis. The labia and clitoris are reduced in size, and the vaginal mucosa becomes thin and dry. The uterus and ovaries also decrease in size.

As discussed previously, pubic hair decreases in amount and becomes gray.

Endocrine System

There is decreased metabolism of thyroxine and decreased conversion of thyroxine to triiodothyronine. Because of a reduction in pancreatic beta cell secretion, hyperglycemia may result. The hypothalamus and the pituitary gland secrete reduced amounts of hormones. An increase in the secretion of antidiuretic hormone and atrial natriuretic hormone may alter fluid balance. There are also increased levels of norepinephrine.

Musculoskeletal System

There is general atrophy of muscles, causing a decline in strength. Muscle wasting is seen most commonly in the distal extremities, especially in the dorsal interosseous muscles.

Osteoclastic activity is greater than osteoblastic activity. An enlargement of the cancellous bone spaces and a thinning of the trabeculae result in osteoporosis. Kyphosis and a loss of height are common (see Fig. 10-6). Degenerative changes and a loss of elastic tissue occur in joints, ligaments, and tendons. This frequently results in joint stiffness. Degenerative changes in bone may result in bone cysts and erosions, making these bones prone to fracture. Osteoarthritis is common. Thinning of cartilage and synovial thickening produce joint stiffness and pain. Range of motion is also reduced, perhaps because of pain. Figure 17-58 shows Heberden’s and Bouchard’s nodes in an 86-year-old woman with osteoarthritis.

Nervous System

Changes in brain function may adversely affect memory and intelligence, although other skills such as language and sustained attention may remain. Significant variability exists among individuals, and many older individuals continue to perform at levels comparable with or exceeding those of much younger people.

Brain weight is frequently reduced 5% to 7% as a result of atrophy of selected areas. There is a decrease in blood flow to the brain by 10% to 15%. Vascular changes of atherosclerosis can result in multiple infarcts or transient ischemic attacks.

Reflexes are commonly reduced; the gag reflex is frequently absent. The Achilles tendon reflex is often symmetrically reduced or absent. Primitive reflexes, such as snout or palmomental, may be present in normal older adults.

Hematopoietic System

There is an increase in the amount of marrow fat and a decrease in the amount of active bone marrow.

Immune System

There is a decreased number of newly formed T lymphocytes and a reduced capability of T lymphocytes to proliferate in response to mitogens or antigens. Humoral immunity is impaired, and suppressor T lymphocytes are decreased in number.

Basic Principles of Geriatric Medicine

Whereas in the younger population the goal of medicine is to cure, the ultimate goal in the geriatric population is to preserve the patient’s quality of life. The health care professional must strive to maintain function and relieve the symptoms that can be relieved. This often involves moving from a doctor-patient relationship alone to a doctor-family or doctor-caregiver relationship. In the event of terminal illness, you should ensure as little mental and physical distress as possible and provide appropriate emotional support to the patient and family. There are a few basic principles of geriatric medicine.

First, there is an altered manifestation of disease. The actual symptom may not be a symptom of the organ system involved with the disease. For example, if a person in his or her 50s were to have a heart attack, the individual, unless diabetic, would usually suffer from chest pain. This is not the case in the geriatric age group. It is well documented that 70% of nondiabetic individuals older than 70 years of age do not have chest pain with a myocardial infarction. Such patients may present instead with breathlessness, falling, confusion, or palpitations.

Another illustration of this alteration in symptoms is the geriatric patient with diabetes mellitus. Ordinarily, because of lack of insulin, younger patients become acidotic and ketotic, with a smell of ketones on their breath. They may also exhibit shallow, rapid respirations. Older patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus may not become ketotic and acidotic. Instead, the syndrome of hyperosmolar, nonketotic coma may ensue. These patients, who do not have the smell of ketones on their breath and are not acidotic, are hyperosmolar and may have serum glucose levels in excess of 600 to 700 mg/dL. They may even present in coma.

A third example is a patient with hyperthyroidism. A geriatric patient with hyperthyroidism might not present with the tachycardia, sweats, or anxiety states that are seen in younger individuals with increased thyroid activity. The geriatric patient may instead appear depressed and apathetic.

An older patient with acute appendicitis might not suffer from abdominal pain, and an older patient with pneumonia might not have shortness of breath; confusion may be the only symptom.

A second principle in geriatric medicine is the nonspecific manifestation of disease. When an older person becomes ill, a family member commonly reports that the patient “just hasn’t gotten out of bed.” The patient may go to bed and stay there. The patient may not want to eat and may have only nonspecific complaints.

A fourth principle is the recognition that multiple pathologic conditions may be present in a geriatric patient. Such a patient may have been given multiple medications or therapies. One medicine may have deleterious effects on a patient if some other condition exists. Of course, this can occur with any patient, but it is more likely to occur in older patients who probably have several pathologic conditions.

A fifth principle is polypharmacy, which is defined as the administration of three or more medicines. It is critical that the interviewer see and know about all the medications being taken by the patient. Instruct the patient or family to bring in all medications, both prescription and nonprescription, and ask the patient how he or she is taking them. There is commonly a significant discrepancy between the written prescription and the dosage that the patient actually takes.

Americans older than 65 years of age use approximately 25% of all prescription medications consumed in the United States, and at any one time, the average geriatric patient uses 4.5 prescription medications. The average nursing home resident consumes the most medications, averaging 8 medications at any one time. The use of mood-altering drugs is common in the geriatric population. Approximately 7% of nursing home residents are taking 3 or more psychoactive drugs.

Finally, what is the patient’s chief complaint? This is sometimes referred to as “the myth of the chief complaint.” Many geriatric patients do not have a single complaint. There may be several problems related to their many conditions. In fact, as already discussed, if a chief complaint is given, it may bear no relationship to the organ system involved. Be careful in the evaluation of the chief complaint when dealing with older patients.

Advance directives are critical for all patients, especially those in the geriatric age group. Advance directives used in the United States take two forms: the living will and the health proxy. The living will is a treatment directive listing interventions that the patient wishes or does not wish to be performed in the event that he or she becomes unable to make such decisions. The health proxy, also known as the durable power of attorney for health care, assigns a surrogate decision maker whom the patient trusts to make decisions for him or her in the event he or she cannot make them. By law, that person cannot be the patient’s physician. These important documents provide an avenue of communication between the physician and the patient on the patient’s end-of-life care. If these documents have not been filed, all too often there may be uncertainty about the patient’s wishes, and the physician and family are left in the dark. Review the video included on Student Consult, which demonstrates how to discuss advance directives.

The Geriatric History

The main components of the medical history are basically the same for geriatric patients as for younger patients, except for the chief complaint and the family history. With the exception of a family history of Alzheimer’s disease, the family history is less important for geriatric patients than for younger patients. For example, the fact that a family member died of a myocardial infarction at 60 years of age is relatively unimportant for a patient who is already in his or her 80s. It is also often difficult for an older patient to remember how and when relatives died.

Before beginning the history, determine whether there is an impairment of hearing, vision, or cognition. A quick check of these three functions is mandatory. Ask the patient whether he or she uses any assistive devices (e.g., hearing aid, glasses, cane, walker, wheelchair). If so, evaluate the condition of the device. Is the patient using the device properly? Ask the patient how the device was obtained; often these devices have been given to the patient by friends or family members or have been left by deceased spouses.

If there is a hearing impairment, sit facing the patient, as close as possible and at ear level with the patient. Make sure that the patient is wearing, if required, the hearing aid or other assistive device. Try to minimize both audible and visual distractions. Speak in a slow, low-pitched, and moderately loud voice. Allow the patient to observe your lips as you talk. Finally, confirm with the patient that he or she is being understood by repeating portions of the history.

Because many older patients have memory deficits or dementia, it is frequently necessary to obtain a confirming history from a family member or caregiver.

All support systems must be evaluated. These include family, friends, and professional services.

Ascertain diet because many older patients have poorly balanced diets.

A comprehensive geriatric assessment is an essential component of the history. It ensures that the patient’s many complex health care needs are evaluated and met. Every geriatric history must include a comprehensive assessment of activities. Measures of the patient’s ability to perform basic activities, called activities of daily living, must be gathered. These activities include bathing, dressing, toileting, continence, feeding, and transferring in and out of bed or on and off a chair. The ability to perform more complex tasks, called instrumental activities of daily living, is also assessed. These tasks include food preparation, shopping, housekeeping, laundry, financial management, medicine management, use of transportation, and use of the telephone.

Other areas that must be evaluated for all geriatric patients are the following:

• Discussion of advance directives1

• Falls

• Incontinence (fecal and urinary)

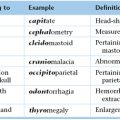

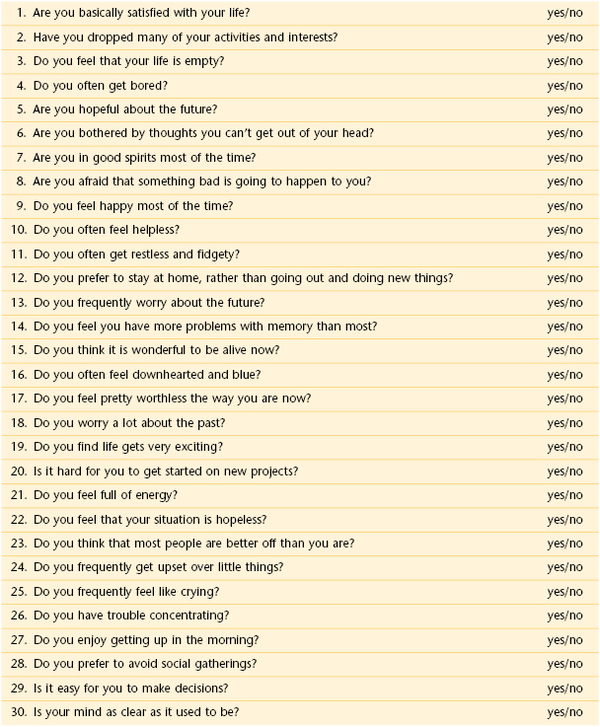

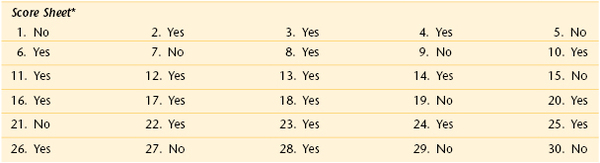

Certain questionnaires and scales have been validated with older persons and may be used to screen patients for affective disorders such as depression or dementia. An example is the Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale, which consists of 30 items (Table 22-1). Each of the patient’s answers that matches the score sheet is scored 1 point. A total score from 0 to 9 is indicative of no depression; from 10 to 19, mild depression; and from 20 to 30, severe depression.

Table 22–1

Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale

* See text for interpretation.

Reprinted from Yesavage JA, et al: Development and validation of a geriatric depression rating scale: a preliminary report, J Psychiatr Res 17:37, 1983. Copyright 1983, with permission from Pergamon Press Ltd. Headington Hill Hall, Oxford 0X3 0BW, UK.

The presentation of depression is not always classic, especially in older individuals. Symptoms suggestive of psychomotor retardation, such as listlessness, decreased appetite, cognitive impairment, and decreased energy, may be important clues.

Finally, an assessment of mental status is required for all older patients. Memory deficits and decreased intellectual functioning influence the reliability of the medical history; therefore, evaluate mental status early in your assessment. Casual conversation is rarely sufficient for detecting cognitive impairment in older patients. All older patients should be screened with the use of a validated instrument such as the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination.2

This test evaluates five areas of mental status: orientation, registration, attention and calculation, recall, and language. Scores of 1 point are given for each correct patient response. In the domain of orientation, knowledge of the date, day, month, year, and season would score 5 points. The maximum score for the complete test is 30. Scores greater than 24 are indicative of no cognitive impairment; patients with scores of 20 to 24 need further testing. Scores lower than 20 are indicative of cognitive impairment.

Effect of Growing Old on the Patient

Growing old can bring great joy and satisfaction: free time to start new hobbies or new occupations; time to travel; time to meet new friends; time to write about lifelong experiences; time to become creative; time to impart wisdom to younger generations; time to enjoy grandparenthood, great-grandparenthood, or even great-great-grandparenthood. Among individuals older than 65 years of age, 94% are grandparents and 46% are great-grandparents. Becoming a grandparent can give an older person a new lease on life and allow him or her to relive the memories of earlier years. Old age can allow the individual to use the knowledge attained throughout life to pursue goals that, perhaps because of time or financial constraints, could not be achieved earlier. All this is true if the patient’s health permits it. The physical and mental health of the person may, however, limit enjoyment of this period of life.

As already discussed, many physical changes occur with aging. Specific disabilities, such as locomotor afflictions, may be particularly handicapping in the presence of normal cognitive functioning. Loss of vision or hearing can lead to social isolation. These physical changes can have a profound effect on the emotional health of the individual. The loss of friends and loved ones may take its toll on the patient as well.

Of the 35 million Americans older than 65 years, it is estimated that 12% to 15% suffer from some functional psychiatric disorder, ranging from anxiety and depression to severe delirium and other psychotic states. Depression may result from loss, which is common among geriatric patients: loss of health, friends, spouses, and relatives, or loss of status or participation in society. These losses and others can be devastating to the older patient.

The patient may feel trapped within an aged body. Grief, a sense of helplessness, or a sense of emptiness can develop. Guilt feelings may also develop: “Why did I outlive. . . ?” In older individuals, as in children, being left alone provokes terror and anger because of a sense of vulnerability. Depression and loss of self-esteem may contribute to suicide, with rates being highest among white men in their 80s.

Finally, concerns and fears related to their own death are important. It is interesting to note that most older individuals fear death less than younger persons do. What older persons fear is not when they will die but how they will die. Will they be in pain? Will they be alone? The health care provider must address these questions directly so that the anxiety and depression so commonly related to these issues can be allayed.

Physical Examination

The physical examination of the geriatric patient is no different from that already described in this book. Special attention, however, should be given to the following areas.

Disrobing may be embarrassing for the older patient, especially because the examiner may be much younger than the patient. Modesty must be respected. Make sure that only the area being examined is exposed. Try to make sure that the room is warm; older individuals tend to become chilled easily. Finally, remember that putting on a robe or gown may not present any difficulty for a younger patient, but for an older patient who may have difficulty moving, perhaps because of arthritis, it can be a real problem.

Assessment of Vital Signs

Perform a routine evaluation, including orthostatic changes in pulse and blood pressure. Be careful if the patient complains of dizziness or chest discomfort. If this occurs, have the patient lie down immediately. Obtain body temperature. If the patient is hypometabolic, as happens in hypothyroidism or in exposure hypothermia, the temperature may be less than 36° C. In the geriatric population, a normal temperature is commonly found in patients with severe infections. Accurate weights should be documented and observed over time.

Skin

Observe the skin for any malignant changes, pressure sores, evidence of pruritus, and ecchymoses suggestive of falls or abuse.

Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat, and Neck

Evaluate the patient for any evidence of skull trauma. Palpate the superficial temporal arteries, which are located anterosuperior to the tragus. In patients who complain of visual symptoms, headaches, or polymyalgic symptoms, polymyalgia rheumatica or temporal (giant cell) arteritis should be suspected (see “Clinicopathologic Correlations” at the end of this chapter).

Is entropion (see Fig. 7-19) or ectropion (see Fig. 7-20) present? Determine visual acuity, if this was not already tested. Eye movement should be checked for gaze palsies. The ability to gaze upward declines with increasing age. Are cataracts present (see Figs. 7-72 and 7-73)? Examine the retina, if a cataract does not exist. Is macular degeneration present (see Figs. 7-125 to 7-127)?

Is cerumen impacted in the external canal (see Fig. 8-4)? Evaluate auditory acuity, if this was not already done.

Ask the patient to remove any dentures, if present. Examine the mouth for dryness, lesions (see Figs. 9-16, 9-17, and 9-20), condition of teeth, oral ulcers (see Fig. 9-45), and malignancies (see Figs. 9-50 and 9-52 to 9-54). Poor-fitting dentures may cause difficulty eating and chewing, which may lead to weight loss. Examine the tongue for malignancy (see Fig. 9-52).

Auscultate the neck. Are carotid bruits present? Palpate the thyroid. Are nodules present? Is the thyroid diffusely enlarged?

Breasts

Examine the breasts for dimpling, discharge, and masses. The incidence of breast cancer increases with advancing age. The incidence is highest among women 85 years of age and older (see Fig. 13-6).

Chest

Inspect the shape of the chest. Is kyphoscoliosis present? Auscultate the chest. Are any adventitious sounds present?

Cardiovascular System

Evaluate the point of maximum impulse. Is it displaced laterally? Auscultate the heart in the four main positions. Are any murmurs, rubs, or gallops heard? Systolic murmurs are heard in 55% of all older adults.

Are the peripheral pulses present? Loss of peripheral pulses is common and may have little clinical significance, especially if the patient does not complain of intermittent claudication. Is there evidence of peripheral vascular disease?

Abdomen

Perform routine palpation and percussion of the abdomen. Is the bladder enlarged? Is a pulsatile abdominal mass present? Palpate for inguinal and femoral hernias. Is there evidence of urine leakage on the undergarments? Perform a rectal examination. Examine the stool for blood. In a man, is the prostate enlarged?

Musculoskeletal Examination

Examine the joints. Ask the patient to stand up from a seated position, and observe for any difficulties. Can the patient lift the hands over the head to brush his or her hair?

The extremities should be examined for arthritis, impaired range of motion, and deformities. The feet should be inspected for nail care, calluses, deformities (see Figs. 17-52 and 17-65), and ulceration (see Figs. 5-126 and 17-66). Evaluate the peripheral pulses.

Neurologic Examination

Evaluate mental status, if this was not already done. Check vibration sense. Lack of vibration sense is the most common deficit in otherwise healthy older individuals. Test reflexes; asymmetry is suggestive of stroke, myelopathy, or root compression. Evaluate for rigidity. Cogwheel rigidity is suggestive of Parkinson’s disease. Perform the Romberg test. Evaluate gait.

Any patient presenting with a change in function must be evaluated for dementia, depression, and Parkinson’s disease.

Evaluate motor strength, tone, and rapid alternating movements.

Clinicopathologic Correlations

Many organ system problems are seen in the geriatric age group. This section covers several disorders and functional states especially common among older individuals and that are not discussed in other chapters of this book.

Senile macular degeneration occurs in nearly 10% of the geriatric population, affecting more women than men. It represents the most common cause of legal blindness in the United States. There is painless and progressive loss of central vision. The patient frequently complains of difficulty reading. Because only the macula is involved, peripheral vision is spared, and complete blindness does not result (see Figs. 7-125 to 7-127).

Temporal arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica are unique to the geriatric age group and probably are manifestations of a condition known also as giant cell arteritis (GCA). GCA is an inflammatory disease of blood vessels, a vasculitis, most commonly involving large and medium arteries of the head, predominantly the branches of the external carotid artery. The name giant cell arteritis reflects the type of inflammatory cell involved as seen on a biopsy. It is more common in women than in men by a ratio of 2 : 1 and more common in those of Northern European descent, as well as those residing at higher latitudes. The mean age of onset is older than 55 years of age, and it is rare in those individuals less than 55 years of age.

The symptoms of temporal arteritis include headache, which is frequently associated with scalp tenderness; the temporal artery may also be tender. There are several generalized symptoms as well, such as fever, weight loss, anorexia, and fatigue. Visual disturbances (see Chapter 7, The Eye) include loss of vision (see Fig. 7-129), blurred vision, diplopia, and amaurosis fugax. Sometimes patients may also complain of pain on chewing food. The diagnosis is made from temporal artery biopsy, which has a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 100%.

Polymyalgia rheumatica is estimated to occur in 40% to 50% of patients with temporal arteritis. Polymyalgia rheumatica is also more common in women than in men. Many patients with polymyalgia rheumatica complain of symmetric pain, especially in the morning, and stiffness of the neck, shoulders, lower back, and pelvic girdle. They often find it difficult to brush their hair. The proximal muscle groups of the upper extremities and pelvic girdle are commonly affected.

Pressure sores, or decubitus ulcers, are serious problems that can lead to pain, a longer hospital stay, and a slower recovery. They are caused by unrelieved pressure that results in damage to underlying tissue. They affect up to 3 million individuals yearly. The annual health care expenditures for these lesions are in excess of $5 billion. It has been estimated that the cost to heal one decubitus ulcer ranges from $5000 to $50,000. In long-term health care facilities, the prevalence of decubitus ulcers is 15% to 25%, whereas the prevalence in the community is 5% to 15%. There are thousands of legal cases each year as a result of the development of pressure sores and the related morbidity and mortality. Bacteremia and deep-tissue injury are common associated problems, and osteomyelitis occurs in more than 25% of all patients with nonhealing decubitus ulcers. A recent study3 from Canada has shown that there has been a decrease in overall prevalence of pressure sores, as well as hospital-acquired pressure sores, in 2009. This is related to more aggressive and earlier therapy. The study indicated that the sores were more commonly found at the heel (41%), the sacrum (19%), or the buttocks (13%).

Decubitus ulcers result from prolonged pressure over bony prominences (see Fig. 22-5). A pressure ulcer starts as reddened skin but gets progressively worse, forming a blister, then an open sore, and finally a crater. The most common places for pressure ulcers are over bony prominences (bones close to the skin) such as the elbows, heels, hips, ankles, shoulders, back, sacrum, and back of the head. It is thought that this pressure causes a decrease in perfusion to the area, leading to the accumulation of toxic products, with subsequent necrosis of skin, muscle, subcutaneous tissue, and bone. Moisture, caused by fecal or urinary incontinence or by perspiration, is also implicated because it causes maceration of the epidermis and allows tissue necrosis to occur. Shearing force is also a factor. Shear is generated when the head of a bed is elevated, causing the torso to slide down and transmit pressure to the sacrum. Poor nutritional status and delayed wound healing are other widespread contributing factors.

Pressure ulcers are staged to classify the degree of damage observed. The four clinical stages of decubitus ulcers are as follows:

Ulcers covered by superficial necrosis must undergo debridement before they can be staged. The patient in Figure 22-5 presented with a stage I pressure sore, and 1 week later, when this photograph was taken, the sore had rapidly advanced to a stage IV lesion. The patient died of sepsis 4 days after the photograph was taken.

Prevention of decubitus ulcers is extremely important in the care of bedridden or chair-bound patients. Repositioning or rotating the patient at least every 2 hours, minimizing moisture, practicing basic skin care, and improving the nutritional state are important. Skin should be cleansed at the time of soiling and at routine intervals. Care should be used to minimize the force and friction applied to the skin.

Urinary incontinence is an important problem in the geriatric age group. It occurs in 15% to 30% of community-dwelling individuals 65 years of age and older. Among institutionalized patients, the prevalence is 40% to 60%. Approximately 12 million adults in the United States have urinary incontinence. It is most common in women older than 50 years. In 2000, the total cost of health care for urinary incontinence was more than $15 billion.

There are many causes of urinary incontinence, including decreased bladder capacity, increased residual volume, medications, diabetes, and pelvic relaxation. In women, thinning and drying of the skin in the vagina or urethra may cause urinary incontinence; in men, an enlarged prostate gland or prostate surgery can cause urinary incontinence. The major transient causes of urinary incontinence can be remembered by the mnemonic “DIAPPERS”:

A: Atrophic vaginitis or urethritis; atonic bladder

P: Psychologic causes such as depression; prostatitis

E: Endocrine abnormalities such as diabetes and hypercalcemia

There are four types of urinary incontinence: stress, urge, overflow, and functional. In stress incontinence, urine leaks because of sudden pressure on the lower abdominal muscles, as during coughing, laughing, or lifting a heavy object. It is very common in women. Urge incontinence occurs when the need to urinate comes on too fast—before the patient can get to a toilet. Urge incontinence is most common in older persons and may be a sign of an infection in the kidneys or bladder. Overflow incontinence is a constant dripping of urine caused by an overfilled bladder. This type of urinary incontinence often occurs in men and can be caused by an enlarged prostate gland or tumor. Diabetes or certain medicines may also cause this problem. Functional incontinence occurs when the patient has normal urine control but has trouble getting to the bathroom in time because of arthritis or other conditions that make it hard to ambulate.

Dementia, according to criteria contained in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, is characterized by an acquired and persistent impairment in short- and long-term memory and other disturbances, such as impairment in language (e.g., reading, writing, fluency, naming, repetition), concentration ability, visuospatial function (e.g., drawing, copying), emotions, and personality, despite a state of clear consciousness. A diagnosis of dementia requires evidence of decline from previous levels of functioning and impairment in multiple cognitive domains for at least six months to support the diagnosis. The prevalence of dementia in the general population 65 years of age is estimated to be 5% to 10%, and the incidence doubles with every additional 5 years. In chronic care facilities, the prevalence is higher than 50% of all hospitalized patients. Despite its prevalence, dementia is often unrecognized in its early stages.

Dementia is not a single disease, but a nonspecific syndrome with many etiologic factors. The most common causes of dementia are strokes and Alzheimer’s disease. The onset and course of the symptoms often provide clues to the cause of dementia. A sudden onset is almost always related to a cerebrovascular accident. A subacute, insidious course may be related to tumor, Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease, or Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia with rigidity and bradykinesia is strongly suggestive of Parkinson’s disease. Dementia in association with urinary incontinence and a spastic, magnetic gait is seen in hydrocephalus. The development of dementia after a fall should raise suspicion of a subdural hematoma.

Some of the symptoms that may be indicative of dementia are difficulty in the following areas:

Falls are a common problem in the geriatric age group. More than 30% of adults 65 years of age and older fall each year. Of those who fall, two thirds fall again within 6 months. Falls are the leading cause of injury-related deaths among people aged 65 years or older and are the most common cause of nonfatal injuries and hospital admissions for trauma. In 2004, the most recent year statistics are available, almost 15,000 people in this age group died from falls, and approximately 1.9 million were treated for injuries in emergency rooms. Older adults account for 75% of deaths from falls. More than half of all fatal falls involve people aged 75 years or older—only 4% of the total population. Among people aged 65 to 69 years, 1 of every 200 falls results in a hip fracture, and among those aged 85 years or older, 1 fall per 10 results in a hip fracture. One fourth of those who fracture a hip die within 6 months of the injury.

The most profound effect of falling is the loss of independent functioning. Of persons who fracture a hip, 25% require lifelong nursing care, and approximately 50% of older adults who sustain a fall-related injury are discharged to a nursing home instead of returning home.

In 2001, more than 1.6 million older adults were treated in emergency departments for all fall-related injuries, nearly 388,000 were hospitalized, and 11,600 people 65 years of age and older died from fall-related injuries. Falls are the result of a decline in vision, balance, sensory perception, strength, and coordination and are often precipitated by medication ingestion. Most falls are sustained by patients who have taken long-acting sedative-hypnotic agents, antidepressants, or major tranquilizers. Whenever possible, try to reduce the number of medications that a patient is taking.

Several modifiable risk factors have been identified with falling. These include lower-body weakness, problems with walking and balance, and taking four or more medications or any psychoactive medications. The health care provider should try to encourage older patients to improve lower body strength and balance through regular physical activity. Tai chi is one exercise program that has been shown to be very effective. In one study, tai chi reduced the number of falls by 47%. All health care providers must also review carefully all of a given patient’s medications to reduce side effects and interactions. Eye examinations to check vision are needed at least once a year.

Approximately half to two thirds of all falls occur in and around the home. Therefore it makes sense to reduce potential home hazards. To make living areas safer, older persons should (1) remove tripping hazards such as throw rugs, (2) use nonslip mats in the bathtub, (3) have grab rails installed next to the toilet and in tub, (4) have handrails installed on both sides of stairways, and (5) improve lighting throughout the home.

The bibliography for this chapter is available at studentconsult.com.

Bibliography

Acierno R, et al. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse, and potential neglect in the United States: the National Elder Mistreatment Study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:292.

Administration on Aging. A profile of older Americans. [Available at] http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/Aging_Statistics/Profile/2009/docs/2009profile_508.pdf; 2009 [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Administration on Aging. Census data and population estimates. [Updated July 1, 2007. Available at] http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/Aging_Statistics/Census_Population/Index.aspx; 2011 [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Aggarwal NK. Reassessing cultural evaluations in geriatrics: insights from cultural psychiatry. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2191.

Allman RM. Pressure ulcers among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:850.

Alzheimer’s Association. 2010 Alzheimer’s disease: facts and figures. [Available at] http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_facts_and_figures.asp [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

American College of Sports Medicine, Chodzko-Zajko W, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand: exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:1501.

American Geriatrics Society. A guide to dementia diagnosis and treatment. [Available at] http://dementia.americangeriatrics.org/; 2010 [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

American Geriatrics Society. A pocket guide to common immunizations for the older adult (≥65 years). [Available at] http://www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/AGS_PocketGuide.pdf [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

American Medical Association. Pain management module 5: assessing and treating pain in older adults. [Updated February 2010. Available at] http://www.ama-cmeonline.com/pain_mgmt/module05/index.htm [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Baker DI, Gottschalk M, Bianco LM. Step by step: integrating evidence-based fall-risk management into senior centers. Gerontologist. 2007;47:548.

Beckett NS, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1887.

Bell AJ, Talbot-Stern JK, Hennessy A. Characteristics and outcomes of older patients presenting to the emergency department after a fall: a retrospective analysis. Med J Aust. 2000;173:176.

Brillhart B. Pressure sore and skin tear prevention and treatment during a 10-month program. Rehabil Nurs. 2005;30(3):85.

Brink TL, Yesavage JA. Geriatric depression rating scale. [Available at] http://www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/Testing.htm [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010–2011 influenza prevention and control recommendations. [Updated November 30, 2012. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/persons.htm [Accessed January 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). [National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003. Updated December 17, 2012. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines and preventable diseases: herpes zoster vaccination for health professionals. [Updated December 14, 2012. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/shingles/hcp-vaccination.htm#recommendations [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Choi H, Palmer MH, Park J. Meta-analysis of pelvic floor muscle training: randomized controlled trials in incontinent women. Nurs Res. 2007;56:226.

Cigolle CT, et al. Geriatric conditions and disability: the health and retirement study. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:156.

Covinsky KE. Dementia, prognosis, and the needs of patients and caregivers. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:573.

Daviglus ML, et al. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement: preventing Alzheimer disease and cognitive decline. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:176.

de Laat EH, Scholte op Reimer WJ, van Achterberg T. Pressure ulcers: diagnostics and interventions aimed at wound-related complaints: a review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:464.

Espinoza SE, Fried LP. Risk factors for frailty in the older adult. Clin Geratr. 2007;15:37.

Evans WJ. Skeletal muscle loss: cachexia, sarcopenia, and inactivity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1123S.

Fancher TL, Kravitz R. In the clinic: depression. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152.

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging. Related statistics: older Americans 2010: key indicators of well-being. [Available at] http://www.agingstats.gov/agingstatsdotnet/Main_Site/Data/2010_Documents/Docs/OA_2010.pdf [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189.

Freedman VA, Martin LG, Schoeni RF. Disability in old age decreased in recent years. JAMA. 2002;288:3137.

Fulmer T. Screening for mistreatment of older adults. Am J Nurs. 2008;108:52.

Ganz DA, et al. Will my patient fall? JAMA. 2007;297:77.

Gonsalves WC, Wrightson AS, Henry RG. Common oral conditions in older persons. Am Fam Physicians. 2008;78:845.

Hall SE, et al. Hip fracture outcomes: quality of life and functional status in older adults living in the community. Aust N Z J Med. 2000;30:327.

Hausdorff JM, Rios DA, Edelber HK. Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1050.

Hazzard HR, Haler JB. Hazzard’s geriatric medicine and gerontology. ed 6. McGraw-Hill: New York; 2009.

Hyde Z, et al. Prevalence of sexual activity and associated factors in men aged 75 to 95 years. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:693.

Iowa Geriatrics Education Center, University of Iowa. Geriatrics assessment tools. [Available at] http://www.healthcare.uiowa.edu/igec/tools/ [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Katz S, Stroud MW. Functional assessment in geriatrics: a review of progress and directions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:267.

Leipzig RM. Update in geriatric medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:1003.

Lim MR, et al. Evaluation of the elderly patient with an abnormal gait. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:107.

Lord SR, Dayhew J. Visual risk factors for falls in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:508.

Lorenz KA, et al. Clinical guidelines: evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:147.

Luggen AS. Wrinkles and beyond: skin problems in older adults. Adv Nurs Pract. 2003;11:55.

Mayeux R. Early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2194.

Morrison RS, Siu AL. Survival in end-stage dementia following acute illness. JAMA. 2000;284:47.

Moyer VA, et al. Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults: US Preventative Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:478.

National Institute on Aging. Age page: alcohol use in older people. [Updated August 10, 2012. Available at] http://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/alcohol-use-older-people [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

National Institutes of Health. NIH Senior Health: caring for someone with Alzheimer’s. [Updated December 2012. Available at] http://nihseniorhealth.gov/alzheimerscare/afterthediagnosis/01.html [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Norton R, Brubaker L. Urinary incontinence in women. Lancet. 2006;367(9504):57.

Panel on Prevention of Falls in Older Persons, American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society. Summary of the updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons, 2010. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:148 http://www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/health_care_pros/JAGS.Falls.Guidelines.pdf.

Qaseem A, et al. Evidence-based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:141.

Querforth HW, LaFerla FM. Mechanisms of disease: Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:329.

Ragia A, Thavendiranathan P, Detsky AS. Does this patient have hearing impairment? JAMA. 2006;295:416.

Reuben D. Medical care for the final years of life: “when you’re 83, it’s not going to be 20 years,”. JAMA. 2009;302:2686.

Rummans TA, Bostwick JM, Clark MM. Maintaining quality of life at the end of life. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:1305.

Seeman TE, et al. Disability trends among older Americans: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1988–1944 and 1999–2004. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:100.

Sherrington C, et al. Effective exercise for the prevention of falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2234.

Silviera MJ, Kim SYH, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1211.

Staats DO. Preventing injury in older adults. Geriatrics. 2008;63:12.

Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305:50.

Tinetti ME, Kumar C. The patient who falls: “it’s always a trade-off,”. JAMA. 2010;303:258.

Tseng HF, et al. Herpes zoster vaccine in older adults and the risk of subsequent herpes zoster disease. JAMA. 2011;305:160.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. [Population Projections Program, Population Division, Washington, DC, 2002. Available at] http://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2012.html [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for dementia: recommendations and rationale. June 2003. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(11):925 http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/3rduspstf/dementia/dementrr.htm.

VanGilder C, et al. The demographics of suspected deep tissue injury in the United States: an analysis of the international pressure ulcer prevalence survey 2006–2009. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2010;23(6):254.

Yeo F. How will the U.S. healthcare system meet the challenge of the ethnogeriatric imperative? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1278.

Yesavage JA, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression rating scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37.

1 These include living wills, “do not resuscitate” orders, and proxy appointments. See also the video clip by scanning the QR code to the left.

2 Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; (800) 331-8378.

3 VanGilder C, MacFarlane GD, Harrison P, et al: The demographics of suspected deep tissue injury in the United States: an analysis of the international pressure ulcer prevalence survey 2006-2009, Adv Skin Wound Care 23(6):254, 2010.