Chapter 7 The genitourinary system

You know my method. It is founded upon the observation of trifles.

Sherlock Holmes, created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930)

The genitourinary history

Presenting symptoms (Table 7.1)

These may include a change in the appearance of the urine, abnormalities of micturition, suprapubic or flank pain or the systemic symptoms of renal failure. Some patients have no symptoms but are found to be hypertensive or to have abnormalities on routine urinalysis or serum biochemistry. Others may feel unwell but not have localising symptoms (Questions box 7.1). The major renal syndromes are set out in Table 7.2.

| Major symptoms |

Questions box 7.1

Questions to ask the patient with renal failure or suspected renal disease

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

Table 7.2 The major renal syndromes

| Name | Definition | Example |

| Nephrotic | Massive proteinuria | Minimal change disease |

| Nephritic | Haematuria, renal failure | Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis |

| Tubulointerstitial nephropathy | Renal failure, mild proteinuria | Analgesic nephropathy |

| Acute renal failure* | Sudden fall in function, rise in creatinine | Acute tubular necrosis |

| Rapidly progressive renal failure | Fall in renal function, over weeks | Malignant hypertension or ‘crescentic’ glomerulonephritis |

| Asymptomatic urinary abnormality | Isolated haematuria, or mild proteinuria | Immunoglobulin A nephropathy |

* Newly defined as acute kidney injury, AKI; Levin A, Warnock D, Mehta R, Kellum J, Shah S, Melitoris B, Ronco C. Improving outcome for AKI. Am J Kidney Dis 2007; 50(1):1–4.

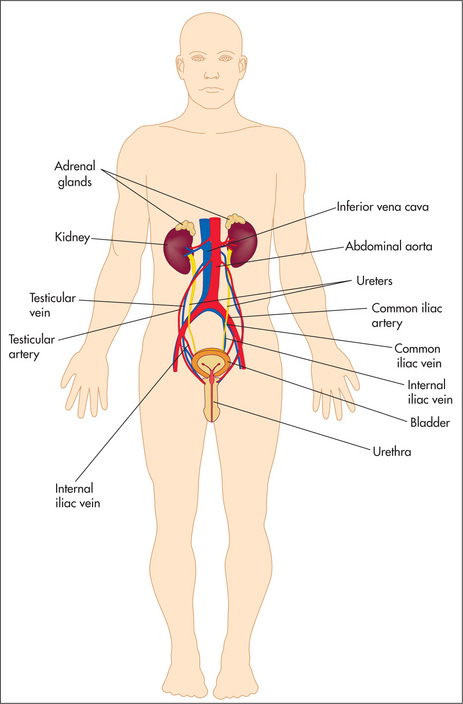

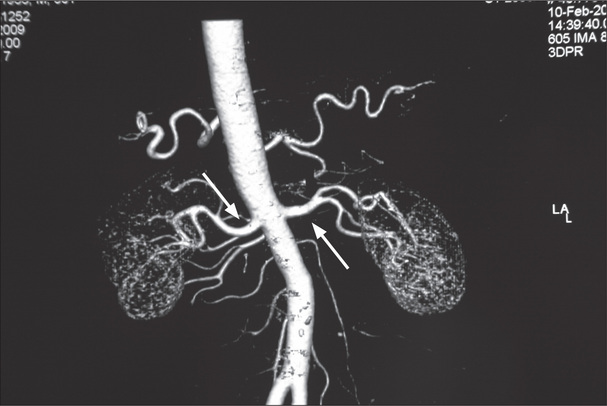

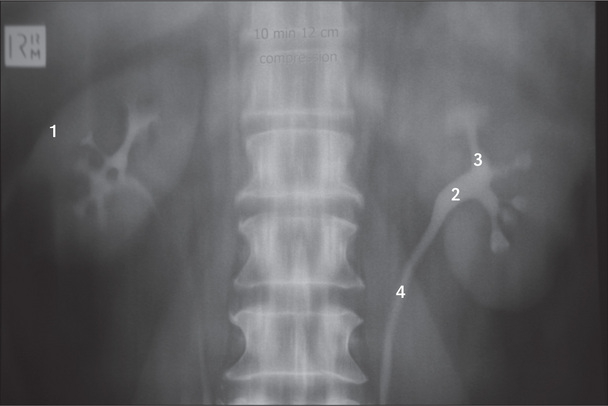

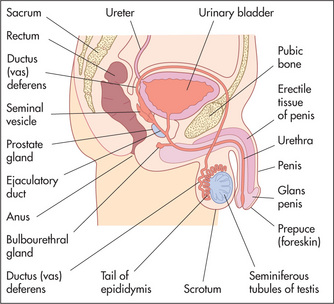

Examination anatomy

Figure 7.1 shows an outline of the anatomy of the urinary tract. Figure 7.2 shows the arterial supply of the kidneys as demonstrated on a CT renal angiogram and Figure 7.3 shows the outline of the renal collecting system. Problems with function can arise in any part, from the arterial blood supply of the kidneys, the renal parenchyma, the ureters and bladder (including their innervation), to the urethra.

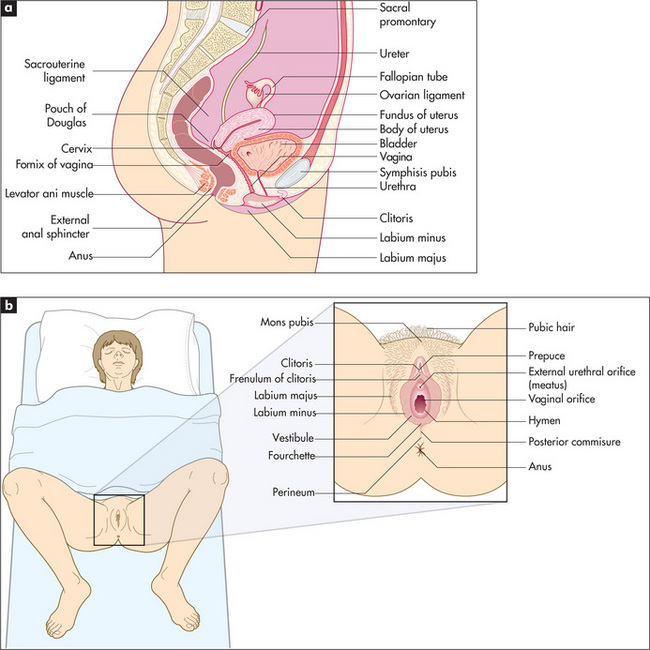

Basic male and female reproductive anatomy is shown in Figures 7.9 (page 216) and 7.13 (page 218).

Change in appearance of the urine

Some patients present with discoloured urine. A red discoloration suggests haematuria (blood in the urine).1 Urethral inflammation or trauma, or prostatic disease, can cause haematuria at the beginning of micturition which then clears, or haematuria only at the end of micturition (Table 7.3). Patients with porphyria can have urine that changes colour on standing. Consumption of certain drugs (e.g. rifampicin) or of large amounts of beetroot and, rarely, haemoglobinuria (due to destruction of red blood cells and release of free haemoglobin) can cause red discoloration of the urine (page 212). Patients with severe muscle trauma may have myoglobinuria as a result of muscle breakdown. This can also cause red discoloration. Foamy, tea-coloured or brown urine may be a presenting sign of nephrosis or kidney failure. It is worth noting that the colour of the urine is not a reliable guide to its concentration.

| 1 Favours urinary tract infection |

Urinary tract infection (UTI)

Urinary tract infection is much more common in women than in men, but there are a number of risk factors for the disease (Table 7.4). It can be strongly suspected on the basis of the patient’s symptoms.2 These include: dysuria (pain or stinging during urination), frequency (need to pass small amounts of urine frequently), haematuria, and loin (more suggestive of upper UTI) or back pain. Physical examination may reveal fevers, rigors, lower abdominal discomfort and loin pain when the renal angle is balloted posteriorly. The latter findings are more suggestive of complicated UTI or pyelonephritis. The presence of a vaginal discharge is against the diagnosis. Elderly patients with a urinary tract infection often present with confusion and few other symptoms or signs. A UTI in a male or frequent, relapsing or recurrent UTI in a female suggests an anatomical abnormality and requires urological evaluation.

| Female sex |

| Coitus |

| Pregnancy |

| Diabetes |

| Indwelling urinary catheter |

| Previous UTI |

| Lower urinary tract symptoms of obstruction |

Urinary obstruction

Urinary obstruction is a common symptom in elderly men and is most often due to prostatism (now called lower urinary tract symptoms—LUTS) or bladder outflow obstruction. The patient may have noticed hesitancy (difficulty starting micturition—urination), followed by a decrease in the size of the stream of urine and terminal dribbling of urine. Strangury (recurrently, a small volume of bloody urine is passed with a painful desire to urinate each time) and pis-en-deux/double-voiding (the desire to urinate despite having just done so) may occur.3 When obstruction is complete, overflow incontinence of urine can occur. Obstruction is associated with an increased risk of urinary infection.

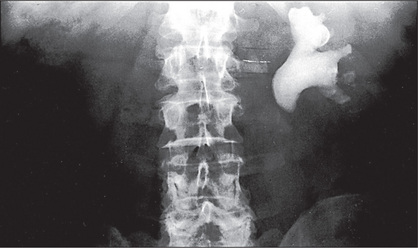

Renal calculi can cause ureteric obstruction (Figure 7.4). The presenting symptom here, however, is usually severe colicky or constant loin or lower quadrant pain which may radiate down towards the symphysis pubis or perineum or testis (renal colic). Urinary obstruction can be a cause of acute renal failure (kidney injury) (Table 7.5).

Table 7.5 Causes of acute renal failure (acute kidney injury, AKI*)

| a. Onset over days |

| This is defined as a rapid deterioration in renal function severe enough to cause accumulation of waste products, especially nitrogenous wastes, in the body. Usually the urine flow rate is less than 20 mL/hour or 400 mL/day, but occasionally it is normal or increased (high-output renal failure). |

| Prerenal |

| Fluid loss: blood (haemorrhage), plasma or water and electrolytes (diarrhoea and vomiting, fluid volume depletion) |

| Hypotension: myocardial infarction, septicaemic shock, drugs |

| Renovascular disease: embolus, dissection or atheroma |

| Increased renal vascular resistance: hepatorenal syndrome |

| Renal |

| Acute-on-chronic renal failure (precipitated by infection, fluid volume depletion, obstruction or nephrotoxic drugs)—see Table 7.7 |

| Acute renal disease: |

Note: Anuria may be due to urinary obstruction, bilateral renal artery occlusion, rapidly progressive (crescentic) glomerulonephritis, renal cortical necrosis or a renal stone in a solitary kidney.

* Levin A, Warnock D, Mehta R, Kellum J, Shah S, Melitoris B, Ronco C. Improving outcome for AKI. Am J Kidney Dis 2007; 50(1):1–4.

Urinary incontinence

Causes of established urinary incontinence include: (i) stress incontinence (instantaneous leakage after the stress of coughing or after a sudden rise in intra-abdominal pressure of any cause)—this problem is more common in women due to vaginal deliveries or an atrophic vaginal wall postmenopause causing a hypermobile urethra; (ii) urge incontinence (overactivity of the detrusor muscle) which is characterised by an intense urge to urinate and then leakage of urine in the absence of cough or other stressors—this occurs in men and women; (iii) detrusor underactivity—this is rare and is characterised by urinary frequency, nocturia and the frequent leaking of small amounts of urine from neurological disease; (iv) overflow incontinence (urethral obstruction)—this occurs typically in men with disease of the prostate, and is characterised by dribbling incontinence after incomplete urination; and (v) a vesico/urethral fistula—a complication of obstructed labour.

Chronic renal failure (chronic kidney disease)

Adequacy of renal function is defined by the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). This is the volume of blood filtered by the kidneys per unit of time. The normal range is 90–120 mL/min. The GFR is estimated by calculating the clearance of creatinine (a normal breakdown product of muscle) from the blood. The serum creatinine and urea levels also provide a measure of accumulation of uraemic toxins and therefore of renal function. Most laboratories now provide an estimated GFR (eGFR) measurement calculated from the serum creatinine and the patient’s age and sex.

A new definition and classification of chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been introduced. CKD is defined as kidney damage or GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 3 months or more, irrespective of cause.5 Further kidney disease has been divided into 6 groups according to GFR (Table 7.6). These allow planning of investigations and treatment that might slow progression of the disease.

Table 7.6 Classification of chronic kidney disease by glomerular filtration rate (GFR)

| Stage | Description | GFR (mL/min/1.73 m3) |

| – | Increased risk for chronic kidney disease (e.g. diabetes, hypertension) | >90 |

| 1 | Kidney damage but normal GFR | >90 |

| 2 | Kidney damage and mild GFR reduction | 60–89 |

| 3 | Moderate reduction in GFR | 30–59 |

| 4 | Severe reduction in GFR | 15–29 |

| 5 | Kidney failure | <15 |

A uraemic patient may present with anuria (defined as failure to pass more than 50 mL urine daily), oliguria (less than 400 mL urine daily), nocturia (the need to get up during the night to pass urine) or polyuria (the passing of abnormally large volumes of urine) (page 297). Nocturia may be an indication of failure of the kidneys to concentrate urine normally, and polyuria may indicate complete inability to concentrate the urine.

The more general symptoms of renal failure include anorexia, vomiting, fatigue, hiccups and insomnia. Pruritus (a general itchiness of the skin), easy bruising and oedema due to fluid retention may also be present. Other symptoms indicating complications include bone pain, fractures because of renal bone disease, and the symptoms of hypercalcaemia (including anorexia, nausea, vomiting, constipation, increased urination, mental confusion) because of tertiary (or primary) hyperparathyroidism.a Patients may also present with the features of pericarditis, hypertension, cardiac failure, ischaemic heart disease, neuropathy or peptic ulceration.

Find out whether the patient is undergoing dialysis and whether this is haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. There are a number of important questions that must be asked of dialysis patients (Questions box 7.2).

Questions box 7.2

Questions to ask the dialysis patient

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

A common form of treatment for renal failure is renal transplantation. A patient may know how well the graft is functioning, and what the most recent renal function tests have shown. Find out whether the patient knows of rejection episodes, how these were treated, and if there has been more than one renal transplant. It is necessary to ascertain if there have been any problems with recurrent infection, urine leaks or side-effects of treatment. Long-term problems with immunosuppression may have occurred, including the development of cancers, chronic nephrotoxicity (e.g. from cyclosporin or tacrolimus), obesity and hypertension from steroids, or recurrent infections. The patient should be aware of the need to avoid skin exposure to the sun and women should know that they need regular Papanicolaoub (Pap) smears for cancer surveillance.

Menstrual and sexual history

A menstrual history should always be obtained. The menarche or date of the first period is important (page 296). The regularity of the periods over the preceding months or years and the date of the last period are both relevant. The patient may complain of dysmenorrhoea (painful menstruation) or menorrhagia (an abnormally heavy period or series of periods).

The sexual history is also relevant.6 Ask about contraceptive methods and the possibility of pregnancy.7 Ask men about erectile dysfunction (impotence). Erectile dysfunction is defined as inability to achieve or maintain a satisfactory erection, for more than 3 months. Most causes are organic (neurogenic [e.g. diabetes] or vascular, or drug related [e.g. beta-blockers, thiazide diuretics]), with a slow onset and loss of morning erections in older men.

Treatment

A detailed drug history must be taken. Note all the drugs, including steroids and immunosuppressants, and their dosages. In patients with decreased renal function, the dosages of many drugs that are cleared by the kidneys must be adjusted. The patient with chronic renal failure should be well informed about the need for protein, phosphate, potassium, fluid or salt restriction. Patients with urinary tract infections may have had a number of courses of antibiotics. Treatment of hypertension should be documented. Certain drugs should be used with caution. For example, non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs can worsen renal function or cause CKD.

Family history

Some forms of renal disease are inherited. Polycystic kidney disease, for example, is an autosomal-dominant condition. Ask about diabetes and hypertension in the family. A family history of deafness and renal impairment suggests Alport’sc syndrome, a hereditary form of nephritis. A family history of kidney disease of any type is a risk factor for development of CKD.

The genitourinary examination

A set examination of the genitourinary system is not routinely performed. However, if renal disease is suspected or known to be present then certain signs must be sought. These are mostly the signs of chronic renal failure (uraemia) and its causes (Table 7.7). On the other hand, examination of the male genitalia or female pelvis is part of the routine general examination.

Table 7.7 Causes of chronic renal failure (chronic kidney disease, CKD*)

| This is defined as a severe reduction in nephron mass over a variable period of time resulting in uraemia.† |

| 1 Glomerulonephritis |

| 2 Diabetes mellitus |

| 3 Systemic vascular disease |

| 4 Analgesic nephropathy |

| 5 Reflux nephropathy |

| 6 Hypertensive nephrosclerosis |

| 7 Polycystic kidney disease |

| 8 Obstructive nephropathy |

| 9 Amyloidosis |

| 10 Renovascular disease |

| 11 Atheroembolic disease |

| 12 Hypercalcaemia, hyperuricaemia, hyperoxaluria |

| 13 Autoimmune diseases |

| 14 Haematological diseases |

| 15 Toxic nephropathies |

| 16 Granulomatous diseases |

| 17 Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis |

| Clinical features suggesting that renal failure is chronic rather than acute |

| Small kidney size (except with polycystic kidneys, diabetes, amyloidosis and myeloma) |

| Renal bone disease |

| Anaemia (with normal red blood cell indices) |

| Peripheral neuropathy |

* Levey A, Eckarrdt K, Tsukanoto Y, Levin A, Coresh J, Rossert J, Zeeuw W, Hostetter T, Lamiere N, Eknoyan G. Definition and classification of CKD: A position statement of KDIGO. Kidney Int 2005; 67:2089–2100.

† Note that this list is not all-inclusive.

General appearance

The general inspection remains crucial. Look for hyperventilation, which may indicate an underlying metabolic acidosis. Hiccupping may be present and can be an ominous sign of advanced uraemia. There may be the ammoniacal fish breath (‘uraemic fetor’) of kidney failure. This musty smell is not easy to describe but once detected is easily remembered. Patients with chronic renal failure commonly have a sallow complexion (a dirty brown appearance or ‘uraemic tinge’). This may be due to impaired excretion of urinary pigments (urochromes) combined with anaemia. The skin colour may be from slate grey to bronze, due to iron deposition in dialysis patients who have received multiple blood transfusions, but these signs are becoming less frequent with the use of exogenous erythropoietin. In terminal renal failure, patients become drowsy and finally sink into a coma due to nitrogen or toxin retention. Twitching due to myoclonic jerks, and tetany and epileptic seizures due to neuromuscular irritability or a low serum calcium level, occur late in renal failure. Over-vigorous correction of acidosis (e.g. with bicarbonate infusions) may also precipitate seizures and coma. There may be typical skin nodules related to calcium phosphate deposition.

The hands

The nails should be inspected: look for leuconychia; Muehrcke’s nailsd refer to paired white transverse lines near the end of the nails; these occur in hypoalbuminaemia (e.g. nephrotic syndrome).8 A single transverse white band (Mees’ lines,e Figure 7.5) may occur in arsenic poisoning, as well as in renal failure. Half-and-half nails (distal nail brown or red, proximal nail pink or white) are also seen in chronic renal failure. Non-pigmented indented transverse bands can occur with any cause of a catabolic state (Beau’s linesf).

Figure 7.5 Mees’ lines

From McDonald FS, ed., Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine, with permission. © Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press.

The arms

An arterio-venous fistula may be visible and palpable in the forearm. A working fistula has a characteristic buzzing feel. This is used for vascular access for dialysis (Figure 7.6).

The chest

Examine the heart and lungs. In chronic renal failure there may be congestive cardiac failure due to fluid retention, and hypertension as a result of sodium and water retention or excess vasoconstrictor activity or both. Signs of pulmonary oedema may also be present due to uraemic lung disease (a type of non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema associated with typical ‘bat’s wing’ pattern on chest X-ray; see Figure 4.61, page 99), volume overload or uraemic cardiomyopathy.

The abdominal examination

Abdominal examination is performed as described on page 194. However, particular attention must be paid to the following.

Inspection

The presence of a Tenckhoff catheter (peritoneal dialysis catheter) should be noted. It is important to look for nephrectomy scars (see Figure 6.18, page 165). These are often more posterior than one might expect. It may be necessary to roll the patient over and look in the region of the loins. Renal transplant scars are usually found in the right or left iliac fossae. A transplanted kidney may be visible as a bulge under the scar, as it is placed in a relatively superficial plane. Peritoneal dialysis results in small scars from catheter placement in the peritoneal cavity; these are situated on the lower abdomen, at or near the midline.

Palpation

Particular care is required here so that renal masses (Table 7.8) are not missed. Remember that an enlarged kidney usually bulges forwards, while perinephric abscesses or collections tend to bulge backwards. Transplanted kidneys in the right or left iliac fossa may be palpable as well. In polycystic kidney disease, hepatomegaly from hepatic cysts may be found (Table 7.9). Feel for the presence of an enlarged bladder. Also palpate for an abdominal aortic aneurysm. In the patient with abdominal pain, renal colic should be suspected if there is renal tenderness (positive LR 3.6) or loin tenderness (positive LR 27.7).9

| 1 Unilateral palpable kidney |

Table 7.9 Adult polycystic kidney disease

| If you find polycystic kidneys, remember these very important points. |

| 1 Take the blood pressure (75% have hypertension). |

| 2 Examine the urine for haematuria (due to haemorrhage into a cyst) and proteinuria (usually less than 2 g/day). |

| 3 Look for evidence of anaemia (due to chronic renal failure) or polycythaemia (due to high erythropoietin levels). Note that the haemoglobin level is higher than expected for the degree of renal failure. |

| 4 Note the presence of hepatomegaly or splenomegaly (due to cysts). These may cause confusion when one is examining the abdomen. |

| 5 Tenderness on palpation may indicate an infected cyst. |

| Note: Subarachnoid haemorrhage occurs in 3% of patients with polycystic kidney disease due to rupture of an associated intracranial aneurysm. As polycystic kidney disease is an autosomal-dominant condition, all family members should also be assessed. |

Balloting

From the French word meaning to shake about, balloting is an examination technique for palpating the kidney by attempting to flick it forward. One hand is placed under the renal angle and the examiner’s fingers flick upwards while the other hand, placed anteriorly in the right or left upper quadrant, waits to feel the kidney move upwards and then float down again (Figure 7.7).

Percussion

This is necessary to confirm the presence of ascites by examining for shifting dullness. Also percuss for an enlarged bladder. Obesity and ascites make direct percussion of the bladder difficult. This is an opportunity to attempt auscultatory percussion.10 The diaphragm of the stethoscope is placed just above the border of the symphysis pubis and direct percussion of the abdominal wall performed, starting at the subcostal margin in the middle line. There is a sudden increase in loudness when the upper border of the bladder is reached. It is even possible to estimate the volume of urine in the bladder by this method. An upper border less than 2 cm from the stethoscope suggests a fairly empty bladder, while an upper border more than 8 cm higher corresponds to a urine volume of between 750 mL and a litre.

Auscultation

The important sign here is the presence of a renal bruit. Renal bruits are best heard above the umbilicus, about 2 cm to the left or right of the midline. Listen with the diaphragm of the stethoscope over both these areas. Next ask the patient to sit up, and listen in both flanks. The presence of a systolic and diastolic bruit is important. A diastolic component makes the bruit more likely to be haemodynamically significant. Its presence suggests renal artery stenosis due to fibromuscular dysplasia or atherosclerosis. Approximately 50% of patients with renal artery stenosis will have a bruit. In a patient with hypertension that is difficult to control, the presence of a systolic/diastolic abdominal bruit has a positive LR for renal artery stenosis of over 40.9 On the other hand, if only a soft systolic bruit is audible, at least half these patients do not have any significant renal artery stenosis. In such cases the aorta or splenic artery may be the source of the sound. The absence of hypertension makes the diagnosis of renal artery stenosis less likely. The occurrence of unexplained pulmonary oedema of sudden onset (‘flash’ pulmonary oedema) in a patient with renal impairment and hypertension makes a diagnosis of renal artery stenosis more likely.

The back

Gentle use of the clenched fist to strike the patient in the renal angle is known as Murphy’s kidney punch (Figure 7.8) and is designed to elicit renal tenderness in patients with renal infection. Similar information may be gained from more gentle balloting of the renal angle when the patient lies supine. Look also for sacral oedema in a patient confined to bed, particularly if the nephrotic syndrome or congestive cardiac failure is suspected. The presence of ulcerations of the toes suggests atheroembolic disease.

The legs

The important signs here are oedema, purpura (page 226), livedo reticularis (a red-blue reticular pattern from vasculitis or atheroembolic disease), pigmentation, scratch marks and signs of peripheral vascular disease. Examination for peripheral neuropathy and myopathy is indicated, as in the arms. Gouty tophi or the presence of gouty arthropathy may very occasionally provide an explanation for the patient’s renal failure (although secondary uric acid retention is common with chronic renal failure, it rarely causes clinical gout).

The urine

Colour

| Colour | Underlying causes |

| Very pale or colourless | Dilute urine (e.g. overhydration, recent excessive beer consumption, diabetes insipidus, post-obstructive diuresis) |

| Yellow-orange | Concentrated urine (e.g. dehydration) |

| Bilirubin | |

| Tetracycline, anthracene, sulfasalazine, riboflavin, rifampin | |

| Brown | Bilirubin |

| Nitrofurantoin, phenothiazines; chloroquine, senna, rhubarb (yellow to brown or red) | |

| Pink | Beetroot consumption |

| Phenindione, phenolphthalein (laxatives), uric acid crystalluria (massive) | |

| Red | Haematuria, haemoglobinuria, myoglobinuria (may also be pink, brown or black) |

| Porphyrins, rifampicin, phenazopyridine, phenytoin, beetroot | |

| Green | Methylene blue, triamterene |

| Black | Severe haemoglobinuria |

| Methyldopa, metronidazole, unipenem | |

| Melanoma, ochronosis; porphryins, alkaptonuria (red to black on standing) | |

| White/milky | Chlyuria |

Transparency

Fainter cloudiness may be due to bacteria. Pus, chyle or blood can cause a more turbid appearance.

Specific gravity

There is a rough correlation between the specific gravity of the urine and its osmolarity. For example, a specific gravity of 1.002 corresponds to an osmolarity of 100 mOsm/kg, while a specific gravity of 1.030 corresponds to 1200 mOsm/kg.

Protein

The colours are compared with a chart provided. The strip tests give only a semi-quantitative measure of urinary protein (+ to ++++) and, if positive, must be confirmed by other tests. It is very important to note that the dipstick is sensitive to albumin but not to other proteins. A reading of + of proteinuria may be normal, as up to 150 mg of protein a day is lost in the urine. Causes of abnormal amounts of protein in the urine are listed in Tables 7.11 and 7.12. Chemical dipsticks do not detect the presence of Bence-Jones proteinuriag (immunoglobulin light chains).

| Persistent proteinuria |

| 1. Renal disease |

| Almost any renal disease may cause a trace of proteinuria. Moderate or large amounts tend to occur with glomerular disease (Table 7.12). |

| 2. No renal disease (functional) |

| Exercise |

| Fever |

| Hypertension (severe) |

| Congestive cardiac failure |

| Burns |

| Blood transfusion |

| Postoperative |

| Acute alcohol abuse |

| Orthostatic proteinuria |

| Proteinuria that occurs when a patient is standing but not when recumbent is called orthostatic proteinuria. In the absence of abnormalities of the urine sediment, diabetes mellitus, hypertension or reduced renal function, this entity probably has a benign prognosis. |

| Definition |

| 1 Proteinuria (>3.5 g per 24 hours) (Note: the other features can all be explained by loss of protein.) |

| 2 Hypoalbuminaemia (serum albumin <30 g/L, due to proteinuria) |

| 3 Oedema (due to hypoalbuminaemia) |

| 4 Hyperlipidaemia (due to increased LDL and cholesterol, possibly from loss of plasma factors that regulate lipoprotein synthesis) |

| Causes |

| Primary renal pathology |

| 1 Membranous glomerulonephritis |

| 2 Minimal change glomerulonephritis |

| 3 Focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis |

| Secondary renal pathology |

| 1 Drugs: e.g. penicillamine, lithium, heroin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| 2 Systemic disease: e.g. SLE, diabetes mellitus, amyloidosis |

| 3 Malignancy: e.g. carcinoma, lymphoma, multiple myeloma |

| 4 Infections: e.g. hepatitis B, hepatitis C, infective endocarditis, malaria, HIV |

LDL = low density lipoprotein.

SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

Glucose and ketones

A semi-quantitative measurement of glucose and ketones is available. Glycosuria usually indicates diabetes mellitus, but can occur with other diseases (Table 7.13). False-positive or false-negative results can occur with vitamin C (large doses), bacteria, oxidising detergents and hydrochloric acid, tetracyclines or levodopa ingestion.

| Glycosuria |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Other reducing substances (false-positives): metabolites of salicylates, ascorbic acid, galactose, fructose |

| Impaired renal tubular ability to absorb glucose (renal glycosuria) |

| • e.g. Fanconi* syndrome (proximal renal tubular disease) |

| Ketonuria |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis |

| Starvation |

* Guido Fanconi (1892–1972), Zürich paediatrician. Considered a founder of modern paediatrics, he described this in 1936. It had previously been described by Guido De-Toni in 1933 and is sometimes called the De-Toni-Fanconi syndrome.

Ketones in the urine of patients with diabetes mellitus are an important indication of the presence of diabetic ketoacidosis (Table 7.13). The three ketone bodies are acetone, beta-hydroxybutyric acid and acetoacetic acid. Lack of glucose (starvation) or lack of glucose availability for the cells (diabetes mellitus) causes activation of carnitine acetyltransferase, which accelerates fatty-acid oxidation in the liver. However, the pathway for the conversion of fatty acids becomes saturated, leading to ketone body formation. The strip colour tests react only to acetoacetic acid. Ketonuria may also be seen associated with fasting, vomiting and strenuous exercise.

Blood

Blood in the urine (haematuria) is abnormal and can be seen with the naked eye if 0.5 mL is present per litre of urine (Table 7.14). Blood may be a contaminant of the urine when women are menstruating. A positive dipstick test is abnormal and suggests haematuria, haemoglobinuria (uncommon) or myoglobinuria (also uncommon). The presence of more than a trace of protein in the urine in addition suggests that the blood is of renal origin. False-positives may occur when there is a high concentration of certain bacteria and false-negative results can occur if vitamin C is being taken.

Table 7.14 Causes of positive dipstick test for blood in the urine

| Haematuria |

| Renal |

| Glomerulonephritis |

| Polycystic kidney disease |

| Pyelonephritis |

| Renal cell carcinoma |

| Analgesic nephropathy |

| Malignant hypertension |

| Renal infarction, e.g. infective endocarditis, vasculitis |

| Bleeding disorders |

| Renal tract |

| Cystitis |

| Calculi |

| Bladder or ureteric tumour |

| Prostatic disease, e.g. cancer, benign prostatic hypertrophy |

| Urethritis |

| Haemoglobinuria |

| Intravascular haemolysis, e.g. microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia, march haemoglobulinuria, prosthetic heart valve, paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria, chronic cold agglutinin disease |

| Myoglobinuria |

| This is due to rhabdomyolysis (muscle destruction): |

Nitrite

If positive, this usually indicates infection with bacteria that produce nitrite. More-specific dipstick tests for white cells are now available; a positive test has an LR of 4.2 for a urinary infection and a negative test has an LR of 0.3.9

The urine sediment

Look for red blood cells, white blood cells and casts.

Red blood cells (RBCs)

These appear as small circular objects without a nucleus. Usually none are seen, although up to 5 RBCs/low-power field (lpf) may be normal in very concentrated urine. If their numbers are increased, try to determine whether the RBCs originate from the glomeruli (more than 80% of the RBCs are dysmorphic—irregular in size and shape) or the renal tract (the RBCs are typically uniform).

Male genitalia

Inspect the genitals (Figures 7.9 and 7.10) for evidence of mucosal ulceration. This can occur in a number of systemic diseases, including Reiter’s syndrome and the rare Behçet’s syndrome. For aesthetic and protective reasons, it is essential to wear gloves for this examination. Retract the foreskin to expose the glans penis. This mucosal surface is prone to inflammation or ulceration in both infective and connective tissue diseases (Table 7.15). Look also for urethral discharge. If there is a history of discharge, attempt to express fluid by compressing or ‘milking’ the shaft. Any fluid obtained must be sent for microscopic examination and culture.

| Ulcerative |

| Herpes simplex (vesicles followed by ulcers: tender) |

| Syphilis (non-tender) |

| Malignancy (squamous cell carcinoma: non-tender) |

| Chancroid (Haemophilus ducreyi infection: tender) |

| Behçet’s syndrome |

| Non-ulcerative |

| Balanitis, due to Reiter’s syndrome or poor hygiene |

| Venereal warts |

| Primary skin disease, e.g. psoriasis |

| Note: Always consider HIV infection. |

Palpate each testis gently using the fingers and thumb of the right hand or cradle the testis between the middle and index fingers of the right hand and palpate it with the ipsilateral thumb.13 The testes are normally equal in size, smooth and relatively firm. Absence of one or both testes may be due to previous excision, failure of the testis to descend, or a retractile testis. In children the testes may retract as examination of the scrotum begins because of a marked cremasteric reflex. A maldescended testis (one that lies permanently in the inguinal canal or higher) has a high chance of developing malignancy. An exquisitely tender, indurated testis suggests orchitis.14 This is often due to mumps in postpubertal patients and occurs about 5 days after the parotitis. An undescended testis may be palpable in the inguinal canal, usually at or above the external inguinal ring. The presence of small firm testes suggests an endocrine disease (hypogonadism) or testicular atrophy due to alcohol or drug ingestion.

A varicocele feels like a bag of worms in the scrotum. The testis on the side of the varicocele often lies horizontally. It is unclear whether this is a cause or effect of the varicocele. A left varicocele is sometimes found when there is underlying left renal tumour or left renal vein thrombosis. The significance of the rarer right varicocele is disputed.15

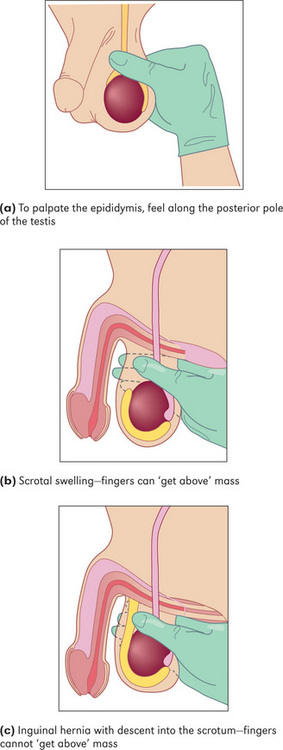

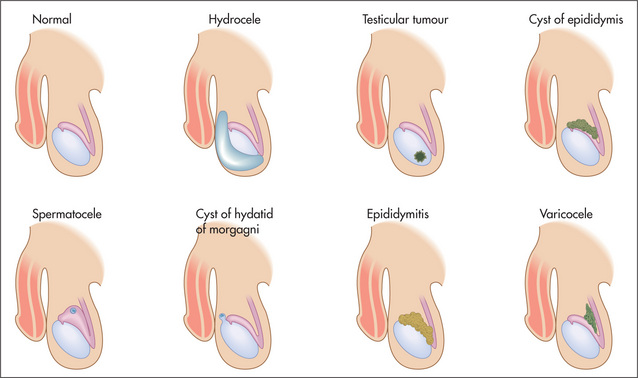

Differential diagnosis of a scrotal mass (Figure 7.11)

If a mass is palpable in the scrotum, decide first whether it is possible to get above it. Have the patient stand up. If no upper border is palpable, it must be descending down the inguinal canal from the abdomen and is therefore an inguino-scrotal hernia (page 178).

Figure 7.11 Differential diagnosis of a scrotal mass

Adapted from Dunphy JE, Botsford TW. Physical examination of the surgical patient. An introduction to clinical surgery, 4th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1975.

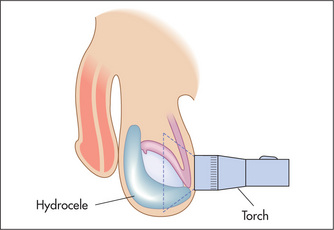

If it is possible to get above the mass, it is necessary to decide whether it is separate from or part of the testis, and to test for translucency. This is performed using a transilluminoscope (a torch) (Figure 7.12). With the patient in a darkened room, a small torch is applied to the side of the swelling by invaginating the scrotal wall. A cystic mass will light up while a solid mass remains dark.

A mass that is part of the testis and that is solid (non-translucent) is likely to be a tumour, or rarely a syphilitic gumma. The testes may be enlarged and hard in men with leukaemia. A mass that is cystic (translucent) with the testis within it is a hydrocele (a collection of fluid in the tunica vaginalis of the testis). A mass that appears separate from the testis and transilluminates is probably a cyst of the epididymis, while a similar mass that fails to transilluminate is probably the result of chronic epididymitis. By feeling along the testicular–epididymal groove it is usually possible to separate an epididymal mass from the testis itself.

Pelvic examination

The pelvic examination should be performed as the final part of any complete physical examination.16 It is essential to obtain informed consent and for male students and doctors to have a chaperone. The patient’s privacy must be promised and ensured. Gloves must be worn (Figure 7.13).

Figure 7.13 Basic female reproductive anatomy

From Douglas G, Nicol F and Robertson C, Macleod’s Clinical Examination, 12th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2009, with permission

The perineum should be brightly illuminated by a lamp. Put a glove on each hand. Inspect first the external genitalia. Note any rash (e.g. sclerotic white areas of leucoplakia, or redness, swelling and excoriation from thrush or trichomoniasis), ulceration, warts, scars, sinus openings or other lesions. Separate the labia with the thumb and forefinger of the right hand. A Bartholinh cyst or abscess is palpated between the thumb and index finger in the posterior part of the labia major; the normal gland is impalpable. Note the size and shape of the clitoris, and the presence or absence of a discharge from the urethral orifice and vaginal outlet. A bloody vaginal discharge suggests menstruation, a miscarriage, cancer or a cervical polyp or erosion. A purulent discharge suggests vaginitis, cervicitis or endometritis (e.g. gonorrhoea) or a retained tampon. Trichomonas vaginalis causes a frothy, watery, pale, yellow-white discharge, while thrush (Candida albicans) causes a thick cheesy discharge associated with excoriations and pruritus. Physiological discharge may be present, this is almost colourless.

Next insert the lubricated index and middle finger into the vagina. Locate the cervix first: it normally points towards the posterior vaginal wall. Note the position, size, shape, consistency, tenderness and mobility. Next palpate the anterior, posterior and lateral fornices. Usually the ovaries are not palpable. If a mass is palpable, its characteristics and location should be noted.

Summary

Examination of a patient with chronic kidney disease: a suggested method (Figure 7.14)

Figure 7.14 Chronic kidney disease examination

Sit the patient up and palpate the back for tenderness and sacral oedema.

Examine the heart for signs of pericarditis or cardiac failure and the lungs for pulmonary oedema.

1. Marazzi P, Gabriel R. The haematuria clinic. BMJ. 1994;308:356.

2. Bent S, Nallamothu BK, Simel DL. Does this woman have an acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection? JAMA. 2002;287(20):2701-2710. Dysuria, frequency, haematuria, back pain and costovertebral tenderness increase the likelihood of urinary tract infection (positive LRs between 1.5 and 2.0). No vaginal discharge or irritation decreased the likelihood

3. Dawson C, Whitfield H. Urological evaluation (ABC of urology). BMJ. 1996;312:695-698. This article provides useful definitions and interpretation of symptoms

4. Moe S, Cunningham J, Goodman W, Martin K, Olgaard K, Ott S, Sprague S, Lamiere N, Eknoyan G. Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: A position statement of the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2006;69:1945-1953.

5. Levey A, Eckarrdt K, Tsukanoto Y, Levin A, Coresh J, Rossert J, Zeeuw W, Hostetter T, Lamiere N, Eknoyan G. Definition and classification of CKD: A position statement of KDIGO. Kidney Int. 2005;67:2089-2100.

6. Dean J. ABC of sexual health: examination of patient with sexual problems. BMJ. 1998;317:1641-1643.

7. Bastian LA, Pistcitelli JT. Is this patient pregnant? Can you reliably rule in or rule out early pregnancy by clinical examination? JAMA. 1997;278:586-591. Clinical features (amenorrhoea, morning sickness, tender breasts, enlarged uterus after 8 weeks with a soft cervix) cannot reliably diagnose early pregnancy—a pregnancy test, however, can

8. Muehrcke RC. The fingernails in chronic hypoalbuminaemia: a new physical sign. BMJ. 1956;1:1327-1328. The classic description of this sign

9. McGee S. Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders; 2007.

10. Guarino JR. Auscultatory percussion of the urinary bladder. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1823-1825. This careful study makes a convincing case for the use of this technique, especially in obese patients or those with ascites

11. Guinan P, Bush I, Ray V, et al. The accuracy of the rectal examination in the diagnosis of prostate carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:499-503. Suggests that rectal examination is an excellent technique for distinguishing benign prostatic hyperplasia and cancer, but this has subsequently been questioned

12. Schroder FH. Detection of prostate cancer. BMJ. 1995;310:140-141.

13. Zornow DH, Landes RR. Scrotal palpation. Am Fam Physician. 1981;23:150-154. Describes standard examination techniques

14. Rabinowitz R, Hulbert WCJr. Acute scrotal swelling. Urol Clin Nth Am. 1995;22:101-105.

15. Roy CR, Wilson T, Raife M, Horne D. Varicocele as the presenting sign of an abdominal mass. J Urol. 1989;141:597-599. A sign of late-stage renal cell carcinoma, due to testicular vein compression, but can be on the left or right side!

16. Deneke M, Wheeler L, Wagner G, Ling FW, Buxton BH. An approach to relearning the pelvic examination. J Fam Pract. 1982;14:782-783. Provides some useful hints

a In secondary hyperparathyroidism, serum calcium is low and phosphate is high. In tertiary hyperparathyroidism, where parathyroid function has become autonomous, serum calcium and phosphate levels are both high.

b Georgios N Papanicolaou (1884–1962). After studying at the University of Athens he worked in the pathology department at New York Hospital.

c Cecil Alport, 1880–1959, South African physician who worked in London and Egypt, described this syndrome in 1927 while working at St Mary’s Hospital, London.

d RC Meuhrcke reported this sign in the British Medical Journal in 1956.

e RA Mees, Dutch physician, reported this sign in 1919. It had previously been reported (1901) in the Lancet by E Reynolds among drinkers of beer contaminated by arsenic in the north of England.

f Joseph Honoré Simon Beau (1806–1865), Paris physician.

g Henry Bence-Jones (1818–73), physician at St George’s Hospital, London, described this in 1848.

h Caspar Bartholin Secundus (1655–1738), professor of philosophy at Copenhagen at the age of 19, then professor of medicine, anatomy and physics. He described the glands in 1677.