Chapter 3 The general principles of physical examination

Students beginning their training in physical examination will be surprised at the formal way this examination is taught and performed.1,2 There are, however, a number of reasons for this formal approach. The first is that it ensures the examination is thorough and that important signs are not overlooked because of a haphazard method.3 The second is that the most convenient methods of examining patients in bed, and for particular conditions in various other postures, have evolved with time. By convention, patients are usually examined from the right side of the bed, even though this may be more convenient only for right-handed people. When students learn this, they often feel safer standing on the left side of the bed with their colleagues in tutorial groups, but many tutors are aware of this device, particularly when they notice all students standing as far away from the right side of the bed as possible.

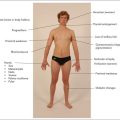

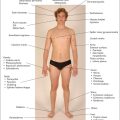

The danger of a systematic approach is that time is not taken to stand back and look at the patient’s general appearance, which may give many clues to the diagnosis. Doctors must be observant, like a detective (Conan Doyle based his character Sherlock Holmes on an outstanding Scottish surgeon).4 Taking the time to make an appraisal of the patient’s general appearance, including the face, hands and body, conveys the impression to the patient (and to the examiners) that the doctor or student is interested in the person as much as the disease. This general appraisal usually occurs at the bedside when patients are in hospital, but for patients seen in the consulting room it should begin as the patient walks into the room and during the history taking, and continue at the start of the physical examination.

Diagnosis has been defined as ‘the crucial process that labels patients and classifies their illnesses, that identifies (and sometimes seals) their likely fates or prognoses and that propels us towards specific treatments in the confidence (often unfounded) that they will do more good than harm’.5

First impressions

First, decide how sick the patient seems to be: that is, does he or she look generally ill or well? The cheerful person sitting up in bed reading Proust (Figure 3.1) is unlikely to require urgent attention to save his life. At the other extreme, the patient on the verge of death may be described as in extremis or moribund. The patient in this case may be lying still in bed and seem unaware of the surroundings. The face may be sunken and expressionless, respiration may be shallow and laboured; at the end of life, respiration often becomes slow and intermittent, with longer and longer pauses between rattling breaths.

Vital signs

Certain important measurements must be made during the assessment of the patient. These relate primarily to cardiac and respiratory function, and include pulse, blood pressure, temperature and respiratory rate. For example, an increasing respiratory rate has been shown to be an accurate predictor of respiratory failure.6 Patients in hospital may have continuous ECG and pulse oximetry monitoring on display on a monitor; these measurements may be considered an extension of the physical examination.

The vital signs must be assessed at once if a patient appears unwell. Patients in hospital have these measurements taken regularly and charted. They provide important basic physiological information.

Facies

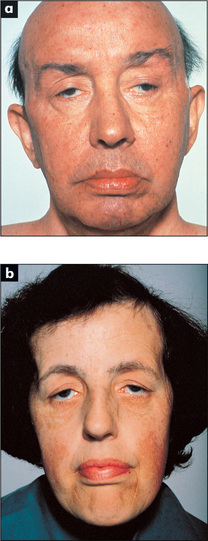

A specific diagnosis can sometimes be made by inspecting the face, its appearance giving a clue to the likely diagnosis. Other physical signs must usually be sought to confirm the diagnosis. Some facial characteristics are so typical of certain diseases that they immediately suggest the diagnosis, and are called the diagnostic facies (Table 3.1 and Figure 3.2). Apart from these, there are several other important abnormalities that must be looked for in the face.

| Amiodarone (anti-arrhythmic drug)—deep blue discoloration around malar area and nose |

| Acromegalic (page 307) |

| Cushingoid (page 309) |

| Down syndrome (page 314) |

| Hippocratic (advanced peritonitis)—eyes are sunken, temples collapsed, nose is pinched with crusts on the lips and the forehead is clammy (page 27) |

| Marfanoid (page 50) |

| Mitral (page 57) |

| Myopathic (page 391) |

| Myotonic (page 392) |

| Myxoedematous (prolonged hypothyroidism) (page 305) |

| Pagetic (page 320) |

| Parkinsonian (page 396) |

| Ricketic (page 314) |

| Thyrotoxic (page 302) |

| Turner’s syndrome (page 314) |

| Uraemic (page 207) |

| Virile facies (page 315) |

Figure 3.2 Some important diagnostic facies: (a) myopathic; (b) myotonic

From Mir MA, Atlas of Clinical Diagnosis, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Saunders, 2003, with permission.

Cyanosis

This refers to a blue discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes; it is due to the presence of deoxygenated haemoglobin in superficial blood vessels. The haemoglobin molecule changes colour from blue to red when oxygen is added to it in the lungs. If more than about 50 g/L of deoxygenated haemoglobin is present in the capillary blood, the skin will have a bluish tinge.7 Cyanosis does not occur in anaemic hypoxia because the total haemoglobin content is low. Cyanosis is more easily detected in fluorescent light than in daylight.

Central cyanosis means that there is an abnormal amount of deoxygenated haemoglobin in the arteries and that a blue discoloration is present in parts of the body with a good circulation, such as the tongue. This must be distinguished from peripheral cyanosis, which occurs when the blood supply to a certain part of the body is reduced and the tissues extract more oxygen than normal from the circulating blood: for example, the lips in cold weather are often blue, but the tongue is spared. The presence of central cyanosis should lead one to a careful examination of the cardiovascular (Chapter 4) and respiratory (Chapter 5) systems (see also Table 3.2).

| Central cyanosis |

Pallor

A deficiency of haemoglobin (anaemia) can produce pallor of the skin and should be noticeable, especially in the mucous membranes of the sclerae if the anaemia is severe (less than 70 g/L of haemoglobin). Pull the lower eyelid down and compare the colour of the anterior part of the palpebral conjunctiva (attached to the inner surface of the eyelid) with the posterior part where it reflects off the sclera. There is usually a marked difference between the red anterior and creamy posterior parts (see Figure 13.3a, page 425). This difference is absent when significant anaemia is present. Although this is at best a crude way of screening for anaemia, it can be specific (though not sensitive) when anaemia is suspected for other reasons as well (Good signs guide 3.1). It should be emphasised that pallor is a sign, while anaemia is a diagnosis based on laboratory results.

| Sign | Positive LR* | Negative LR† |

| Pallor at multiple sites | 4.5 | 0.7 |

| Facial pallor | 3.8 | 0.6 |

| Palm crease pallor | 7.9 | NS |

| Conjunctival pallor | 16.7 | − |

NS = not significant.

* Positive likelihood ratio: when the finding is present, describes the probability change. The higher the LR is above 1, the more likely there is disease.

† Negative likelihood ratio: when the finding is absent, describes the probability change. The closer the LR is to 0, the more likely there is not disease.

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

Facial pallor may also be found in shock, which is usually defined as a reduction of cardiac output such that the oxygen demands of the tissues are not being met (Table 3.3). These patients usually appear clammy and cold and are significantly hypotensive (have low blood pressure) (page 27). Pallor may also be a normal variant due to a deep-lying venous system and opaque skin.

Hair

Bearded or bald women and hairless men not uncommonly present to doctors. These conditions may be a result of more than the rich normal variations of life, and occasionally are due to endocrine disease (Chapter 10).

Weight, body habitus and posture

Look specifically for obesity. This is most objectively assessed by calculation of the body mass index (BMI), where the weight in kilograms is divided by the height in metres squared. Normal is less than 25°kg/m2. A BMI of ≥ 30 indicates frank obesity. Morbid obesity is a BMI ≥40. Medical risks are increasingly recognised in association with obesity (Table 3.4).

TABLE 3.4 Medical conditions associated with obesity (BMI ≥ 30)

Severe underweight (BMI <18.5) is called cachexia.8 Look for wasting of the muscles, which may be due to neurological or debilitating disease, such as malignancy.

Note excessively short or tall stature, which may be rather difficult to judge when the patient is lying in bed (page 313). Inspect for limb deformity or missing limbs (rather embarrassing if missed in viva voce examinations) and observe if the physique is consistent with the patient’s stated chronological age. A number of body shapes are almost diagnostic of different conditions (Table 3.5). If the patient walks into the examining room, the opportunity to examine gait should not be lost: the full testing of gait is described in Chapter 11.

TABLE 3.5 Some body habitus syndromes

Hydration

Although this is not easy to assess, all doctors must be able to estimate the approximate state of hydration of a patient.9–11 For example, a severely dehydrated patient is at risk of death from developing acute renal failure, while an overhydrated patient may develop pulmonary oedema.

For a traditional assessment of dehydration (Table 3.6), inspect for sunken orbits, dry mucous membranes and the moribund appearance of severe dehydration. Reduced skin turgor (pinch the skin: normal skin returns immediately on being released) occurs in moderate and severe dehydration (this traditional test is not of proven value, especially in the elderly, whose skin may always be like that). The presence of dry axillae increases the likelihood of dehydration and a moist tongue reduces the likelihood, but the other signs are in fact of little proven value (Good signs guide 3.2).

TABLE 3.6 Classical physical signs of dehydration (of variable reliability—see Good signs guide 3.2)

Note: Total body water in a man of 70 kg is about 40 L.

Good signs guide 3.2 Hypovolaemia

| Sign | Positive LR | Negative LR |

| Dry axillae | 2.8 | NS |

| Dry mucous membranes; nose and mouth | NS | 0.3 |

| Sunken eyes | NS | 0.5 |

| Confusion | NS | NS |

| Speech not clear | NS | 0.5 |

NS = not significant.

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

Take the blood pressure (page 54) and look for a fall in blood pressure when the patient sits or stands up after lying down. The patient should stand, if he or she can, for at least 1 minute before the blood pressure is taken again (the inability of the patient to stand because of postural dizziness is probably a more important sign than the blood pressure difference). This is called postural hypotension. An increase in the pulse rate of 30 or more, when the patient stands, is also a sign of hypovolaemia.

Assessment of the patient’s jugular venous pressure is one of the most sensitive ways of judging intravascular volume overload, or overhydration (see Chapter 4).

The hands and nails

There is probably no subspecialty of internal medicine in which examination of the hands is not rewarding. The shape of the nails may change in some cardiac and respiratory diseases, the whole size of the hand may increase in acromegaly (page 307), gross distortion of the hands’ architecture occurs in some forms of arthritis (page 250), tremor or muscle wasting may represent neurological disease (page 354), and pallor of the palmar creases may indicate anaemia (Table 3.7). These and other changes in the hands await you later in the book.

| Nail sign | Some causes | Page no. |

| Blue nails | Cyanosis, Wilson’s disease, ochronosis | 25 |

| Red nails | Polycythaemia (reddish-blue), carbon monoxide poisoning (cherry-red) | 236 |

| Yellow nails | Yellow nail syndrome | 132 |

| Clubbing | Lung cancer, chronic pulmonary suppuration, infective endocarditis, cyanotic heart disease, congenital, HIV infection, chronic inflammatory bowel disease, etc. | 50 |

| Splinter haemorrhages | Infective endocarditis, vasculitis | 50 |

| Koilonychia (spoon-shaped nails) | Iron deficiency, fungal infection, Raynaud’s disease | 224 |

| Pale nail bed | Anaemia | 224 |

| Onycholysis | Thyrotoxicosis, psoriasis | 301 |

| Non-pigmented transverse bands in the nail bed (Beau’s lines) | Fever, cachexia, malnutrition | 208 |

| Leuconychia (white nails) | Hypoalbuminaemia | 159 |

| Transverse opaque white bands (Muehrcke’s lines) | Trauma, acute illness, hypoalbuminaemia (also caused by chemotherapy) | 208 |

| Single transverse white band (Mees’ lines) | Arsenic poisoning, renal failure (also caused by chemotherapy or severe illness) | 208 |

| Nailfold erythema and telangiectasia | Systemic lupus erythematosus | 282 |

| ‘Half and half nails’ (proximal portion white to pink and distal portion red or brown: Terry’s nails) | Chronic renal failure, cirrhosis | 208 |

Temperature

The temperature should always be recorded as part of the initial clinical examination of the patient. The normal temperature (in the mouth) ranges from 36.6°C to 37.2°C (98°F to 99°F) (Table 3.8). The rectal temperature is normally higher and the axillary and tympanic temperature lower than the oral temperature (Table 3.8). In very hot weather the temperature may rise by up to 0.5°C. Patients who report they have a fever are usually correct, as is a mother who reports that her child’s forehead is warm and that fever is present (Good signs guide 3.3).

| Normal | Fever | |

| Mouth | 36.8°C | >37.3°C |

| Axilla* | 36.4°C | >36.9°C |

| Rectum | 37.3°C | >37.7°C |

* Tympanic temperatures are similar to axillary ones.

| Sign | Positive LR | Negative LR |

| Patient says has fever | 4.9 | 0.2 |

| Warm forehead | 2.5 | 0.4 |

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

There is a diurnal variation; body temperature is lowest in the morning and reaches a peak between 6.00 and 10.00 p.m. The febrile pattern of most diseases follows this diurnal variation. The pattern of the fever (pyrexia) may be helpful in diagnosis (Table 3.9).

| Type | Character | Examples |

| Continued | Does not remit | Typhoid fever, typhus, drug fever, malignant hyperthermia |

| Intermittent | Temperature falls to normal each day | Pyogenic infections, lymphomas, miliary tuberculosis |

| Remittent | Daily fluctuations >2°C, temperature does not return to normal | Not characteristic of any particular disease |

| Relapsing | Temperature returns to normal for days before rising again | Malaria: |

| Tertian—3-day pattern, fever peaks every other day (Plasmodium vivax, P. ovale); Quartan—4-day pattern, fever peaks every 3rd day (P. malariae) | ||

| Lymphoma: | ||

| Pel-Ebstein* fever of Hodgkin’s disease (very rare) | ||

| Pyogenic infection |

Note: The use of antipyretic and antibiotic drugs has made these patterns unusual today.

* Pieter Pel (1859−1919), Professor of Medicine, Amsterdam; Wilhelm Ebstein (1836–1912), German physician

Very high temperatures (hyperpyrexia, defined as above 41.6°C) are a serious problem and may result in death. The causes include heat stroke from exposure or excessive exertion (e.g. in marathon runners), malignant hyperthermia (a group of genetically determined disorders in which hyperpyrexia occurs in response to various anaesthetic agents [e.g. halothane] or muscle relaxants [e.g. suxamethonium]), the neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and hypothalamic disease.

Hypothermia is defined as a temperature of less than 35°C. Normal thermometers do not record below 35°C and therefore special low-reading thermometers must be used if hypothermia is suspected. Causes of hypothermia include hypothyroidism and prolonged exposure to cold (page 304).

Smell

Certain medical conditions are associated with a characteristic odour.12 These include the sickly sweet acetone smell of the breath of patients with ketoacidosis, the sweet smell of the breath in patients with liver failure, the ammoniacal fish breath (‘uraemic fetor’) of kidney failure and, of course, the stale cigarette smell of the patient who smokes. This smell will be on his or her clothes and even on the referral letter kept in a bag or pocket next to a packet of cigarettes. The recent consumption of alcoholic drinks may be obvious and ‘bad breath’, although often of uncertain cause, may be related to poor dental hygiene, gingivitis (infection of the gums) or nasopharyngeal tumours. Chronic suppurative infections of the lung can make the breath and saliva foul-smelling. Skin abscesses may be very offensive, especially if caused by anaerobic organisms or Pseudomonas spp. Urinary incontinence is associated with the characteristic smell of stale urine, which is often more offensive if the patient has a urinary tract infection. The smell of bacterial vaginosis is usually just described as offensive. Severe bowel obstruction and the rare gastrocolic fistula can cause faecal contamination of the breath when the patient belches. The black faeces (melaena) caused by gastric bleeding and the breakdown of blood in the gut has a strong smell, familiar to anyone who has worked in a ward for patients with gastrointestinal illnesses. The metallic smell of fresh blood, sometimes detectable during invasive cardiological procedures, is very mild by comparison.

Evidence-based clinical examination

History taking and physical examination are latecomers to evidence-based medicine. There are big efforts in all areas of medicine to base practice on evidence of benefit.

By their nature, physical signs tend to be subjective and one examiner will not always agree with another. For example, the loudness of a murmur or the presence or absence of fingernail changes may be controversial. There are often different accepted methods of assessing the presence or absence of a sign, and experienced clinicians will often disagree about whether, for example, the apex beat is in the normal position or not. Even apparently objective measurements such as the blood pressure can vary depending on whether Korotkov sound IV or V (page 55) is used, and from minute to minute for the same patient. Some physical signs are present only intermittently; the pericardial rub may disappear before students can be found in the games room to come and listen to it.

You may find it helpful to use the following mnemonics to help you remember this: SpIn = Specific tests when positive help to rule In disease and SnOut = Sensitive tests when negative help rule Out disease.

The likelihood that a test or sign result will be a true positive or negative depends on the pre-test probability of the presence of the condition. For example, if splinter haemorrhages (page 50) are found in the nails of a well manual labourer they are likely to represent a false positive sign of infective endocarditis. This sign is not very sensitive or specific and in this case the pre-test probability of the condition is low. If splinters are found in a sick patient with known valvular heart disease and a new murmur, the sign is likely to be a true positive in this patient with a high pre-test probability of endocarditis. This pre-test probability analysis of the false and true positive rate is based on Bayes’ theorem.

A useful way to look at sensitivity and specificity is the likelihood ratio (LR). A positive LR,

indicates that the presence of a sign is likely to occur that much more often in an individual with the disease than in one without it. The higher the positive LR, the more useful is a positive sign. A negative likelihood ratio increases the likelihood that the disease is absent if the sign is not present.

Remember that if the LR is greater than 1 there is an increased probability of disease; if the LR is less than 1 there is a decreased probability of disease.

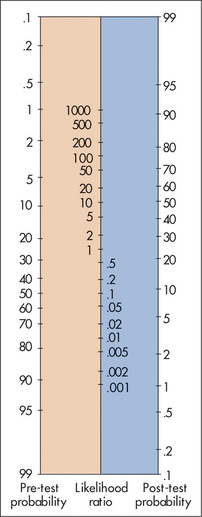

All these figures are calculated on a population suspected of disease; it would be quite incorrect to apply them to an asymptomatic group of people. Fagan’s nomogram (Figure 3.3) can be used to apply LRs to clinical problems if the pre-test probability of the condition is known or can be estimated. Remember, positive LRs of 2, 5 and 10 increase the probability of disease by 15%, 30% and 45%, respectively. Similarly, negative LRs of 0.5, 0.2 and 0.1 decrease the probability of disease by 15%, 30% and 45% respectively.

When the pre-test probability is very low, even a high positive LR does not make the disease very likely. A line is drawn from the pre-test probability number through the known LR and ends up on the post-test probability number. For example, if the pre-test probability of the condition is low, say 10 (10%) and a sign is present which has an LR of 2, the post-test probability of the condition being present is only about 20%. We have included the LRs in tables of Good signs guides in most chapters of this book.

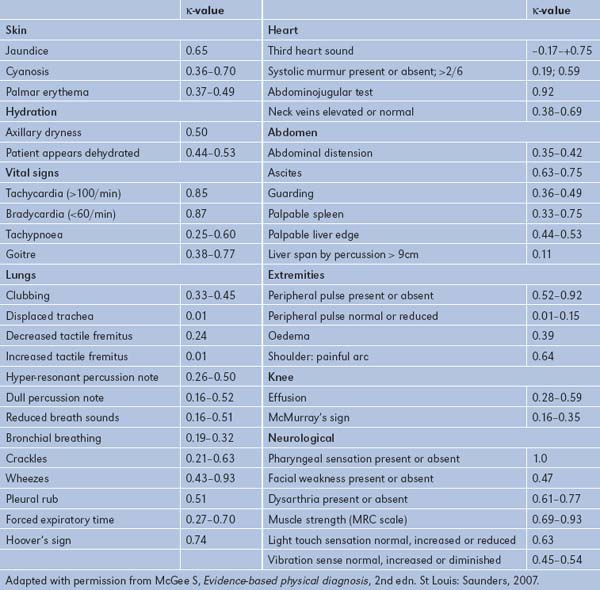

Inter-observer agreement (reliability) and the κ-statistic

The LR of a sign assumes that the sign is present but there is considerable variability in the agreement between observers about the presence of many signs. There are a number of reasons for this low reliability (Table 3.10).

TABLE 3.10 Important reasons for inter-observer disagreement

| 1 The sign comes and goes; e.g. basal crackles in heart failure, a fourth heart sound |

| 2 Some of the observers’ technique may be imperfect; e.g. not asking the patient to cough before declaring the presence of lung crackles consistent with heart failure |

| 3 Some signs are intrinsically subjective; e.g. the grading of the loudness of a murmur |

| 4 Preconceptions about the patient based on other observations or the history may influence the observer; e.g. goitre may seem readily palpable when a patient is known to have thyroid disease |

| 5 The examination conditions may not be ideal; e.g. attempting to listen to the heart in a noisy clinic when the patient is sitting in a chair and not properly undressed |

The κ (kappa) statistic is a way of expressing the inter-observer variation for a sign or test. Values are between 0 and 1, where 0 means the agreement about the sign is the same as it would be by chance and 1 means complete (100%) agreement. Occasionally values of less than 0 are obtained when inter-observer agreement is worse than should occur by chance. By convention a κ-value of 0.8 to 1 means almost or perfect agreement, 0.6 to 0.8 substantial agreement, 0.2 to 0.4 fair agreement, and 0 to 0.2 slight agreement. A selection of signs and their κ-values is listed in Table 3.11. Remember that a high κ-value means agreement about the presence of a sign, not that the sign necessarily has a high LR. A low κ-value may be an indication that the sign is a difficult one to elicit accurately, especially for beginners, but it does not always mean that the sign is not useful.

1. Sacket DL. The science of the art of clinical examination. JAMA. 1992;267:2650-2652. Examines the limitations of current research in the field of clinical examination

2. Sackett DL. A primer on the precision and accuracy of the clinical examination (the rational clinical examination). JAMA. 1992;267:2638-2644. An important article examining the relevance of understanding both precision (reproducibility among various examiners) and accuracy (determining the truth) in clinical examination

3. Wiener S, Nathanson M. Physical examination: frequently observed errors. JAMA. 1976;236:852-855. This article categorises errors, including poor skills, under-reporting and over-reporting of signs, use of inadequate equipment and inadequate recording

4. Fitzgerald FT, Tierney LMJr. The bedside Sherlock Holmes. West J Med. 1982;137:169-175. Here deductive reasoning is discussed as a tool in clinical diagnosis

5. Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Tugwell P. Clinical epidemiology. A basic science for clinical medicine. Boston: Little, Brown & Co; 1985. The perceived commonness of diseases affects our approach to their diagnosis

6. Cretikos MA, Bellomo R, Hillman K, Chen J, Finfer S, Flabouris A. Respiratory rate: the neglected vital sign. Med J Aust. 2008;188(11):657-659.

7. Martin L, Khalil H. How much reduced hemoglobin is necessary to generate central cyanosis? Chest. 1990;97:182-185. This useful article explains the chemistry of haemoglobin and its colour change

8. Detsky AS, Smalley PS, Chang J. Is this patient malnourished? JAMA. 1994;271:54-58. Assessment of nutrition is an important part of the examination but needs a scientific approach

9. Gross CR, Lindquist RD, Woolley AC, et al. Clinical indicators of dehydration severity in elderly patients. J Emerg Med. 1992;10:267-274. This important and urgent assessment is more difficult in elderly sick patients

10. Koziol-McLain J, Lowenstein SR, Fuller B. Orthostatic vital signs in emergency medicine department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:606-610. These signs help in the assessment of the severity of illness in emergency patients but there is a wide range of normal

11. McGee S, Abernethy WBIII, Simel DL. Is this patient hypovolemic?. JAMA 1999;281:1022-1029. The most sensitive clinical features for large-volume blood loss are severe postural dizziness and a postural rise in pulse rate of >30 beats a minute, not tachycardia or supine hypotension. A dry axilla supports dehydration. Moist mucous membranes and a tongue without furrows make hypovolaemia unlikely; assessing skin turgor, surprisingly, is not of proven value.

12. Hayden GF. Olfactory diagnosis in medicine. Postgrad Med. 1980;67:110-115. 118 Describes characteristic patient odours and their connections with disease, although the diagnostic accuracy is uncertain

Beaven DW. Color atlas of the nail in clinical diagnosis, 3rd edn. Chicago: Mosley Year Book; 1996.

Browse NL. An introduction to the symptoms and signs of surgical disease, 4th edn. London: Edward Arnold; 2005.

Joshua AM, Celermajer DS, Stockler MR. Beauty is in the eye of the examiner: reaching agreement about physical signs and their value. Intern Med J. 2005;35:178-187.

Lumley JJP. Hamilton Bailey’s demonstrations of physical signs in clinical surgery, 18th edn, Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1997.

McGee S. Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. Saunders: St Louis; 2007.

McHardy KC, et al. Illustrated signs in clinical medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone; 1997.

Orient JM. Sapira’s art and science of bedside diagnosis, 3rd edn. Baltimore: Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Schneiderman H, Peixoto AJ. Bedside diagnosis. An annotated bibliography of literature on physical examination and interviewing, 3rd edn. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 1997. A superb summary of the evidence base for clinical examination

Zatouroff M. Color atlas of physical signs in general medicine, 2nd edn. Chicago: Mosby Year Book; 1996.