Chapter 1 The general principles of history taking

An extensive knowledge of medical facts is not useful unless a doctor is able to extract accurate and succinct information from a sick person about his or her illness. In all branches of medicine, the development of a rational plan of management depends on a correct diagnosis or sensible, differential diagnosis (list of possible diagnoses). Except for patients who are extremely ill, taking a careful medical history should precede both examination and treatment. A medical history is the first step in making a diagnosis; it will often help direct the physical examination and will usually determine what investigations are appropriate. More often than not, an accurate history suggests the correct diagnosis, whereas the physical examination and subsequent investigations merely serve to confirm this impression.1,2 The history is also, of course, the least expensive way of making a diagnosis.

Bedside manner and establishing rapport

History taking requires practice and depends very much on the doctor–patient relationship.3 It is important to try to put the patient at ease immediately, because unless a rapport is established, the history taking is likely to be unrewarding.

There is no doubt that the treatment of a patient begins the moment one reaches the bedside or the patient enters the consulting rooms. The patient’s first impressions of a doctor’s professional manner will have a lasting effect. One of the axioms of the medical profession is primum non nocere (the first thing is to cause no harm).4 An unkind and thoughtless approach to questioning and examining a patient can cause harm before any treatment has had the opportunity to do so. You should aim to leave the patient feeling better for your visit. This is a difficult technique to teach. Much has been written about the correct way to interview patients, but each doctor has to develop his or her own method, guided by experience gained from clinical teachers and patients.5–8

To help establish this good relationship, the student or doctor must make a deliberate point of introducing him- or herself and explaining his or her role. This is especially relevant for students or junior doctors seeing patients in hospital. A student might say: ‘Good afternoon, Mrs Evans. My name is Jane Smith; I am Dr Osler’s medical student. She has asked me to come and see you.’ A patient seen at a clinic should be asked to come and sit down, and be directed to a chair. The door should be shut or, if the patient is in the ward, the curtains drawn to give some privacy. The clinician should sit down beside or near the patient so as to be close to eye level and give the impression that the interview will be an unhurried one.9,10 It is important here to address the patient respectfully and use his or her name and title. Some general remarks about the weather, hospital food or the crowded waiting room may be appropriate to help put the patient at ease, but these must not be patronising.

Obtaining the history

The final record must be a sequential, accurate account of the development and course of the illness or illnesses of the patient (Appendix I, page 461). There are a number of methods of recording this information. Hospitals may have printed forms with spaces for recording specific information. This applies especially to routine admissions (e.g. for minor surgical procedures). Follow-up consultation questions and notes will be briefer than those of the initial consultation; obviously, many questions are only relevant for the initial consultation. When a patient is seen repeatedly at a clinic or in a general practice setting, the current presenting history may be listed as an ‘active’ problem and the past history as a series of ‘inactive’ or ‘still active’ problems.

A sick patient will sometimes emphasise irrelevant facts and forget about very important symptoms. For this reason, a systematic approach to history taking and recording is crucial (Table 1.1).11

| 1 Presenting (principal) symptom (PS) |

| 2 History of presenting illness (HPI) |

Introductory questions

The next step after introducing oneself should be to find out the patient’s major symptoms or medical problems. Asking the patient ‘What brought you here today?’ can be unwise, as it often promotes the reply ‘an ambulance’ or ‘a car’. This little joke wears thin after some years in clinical practice. It is best to attempt a conversational approach and ask the patient ‘What has been the trouble or problem recently?’ or ‘When were you last quite well?’ For a follow-up consultation some reference to the last visit is appropriate, for example: ‘How have things been going since I saw you last?’ or ‘It’s about … weeks since I saw you last, isn’t it? What’s been happening since then?’ This lets the patient know the clinician hasn’t forgotten him or her. Some writers suggest the clinician begin with questions to the patient about more general aspects of his or her life. There is a danger that this attempt to establish early rapport will seem intrusive to a person who has come for help about a specific problem, albeit one related to other aspects of his or her life. This type of general and personal information may be better approached once the clinician has shown an interest in the presenting problem or as part of the social history. The best approach and timing of this part of the interview must vary, depending on the nature of the presenting problem and the patient’s and clinician’s attitude. Encourage patients to tell their story in their own words from the onset of the first symptom to the present time.

When a patient stops volunteering information, the question ‘What else?’ may start things up again.8 However, some direction may be necessary to keep a garrulous patient on track later during the interview. It is necessary to ask specific questions to test diagnostic hypotheses. For example, the patient may not have noticed an association between the occurrence of chest discomfort and exercise (typical of angina) unless asked specifically. It may also be helpful to give a list of possible answers. A patient with suspected angina who is unable to describe the symptom may be asked if the sensation was sharp, dull, heavy or burning. The reply that it was burning makes angina less likely.

The clinician must learn to listen with an open mind.10 The temptation to leap to a diagnostic decision before the patient has had the chance to describe all the symptoms in his or her own words should be resisted. Avoid using pseudo-medical terms; and if the patient uses these, find out exactly what is meant by them, as misinterpretation of medical terms is common.

Some patients may have medical problems that make the interview difficult for them; these include deafness and problems with speech and memory. These must be recognised by the clinician if the interview is to be successful. See Chapter 2 for more details.

History of the presenting illness

Current symptoms

Onset (Mode of onset and pattern)

Find out whether the symptom came on rapidly, gradually or instantaneously. Some cardiac arrhythmias are of instantaneous onset and offset. Sudden loss of consciousness (syncope) with immediate recovery occurs with cardiac but not neurological disease. Ask whether the symptom has been present continuously or intermittently. Determine if the symptom is getting worse or better, and, if so, when the change occurred. For example, the exertional breathlessness of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may come on with less and less activity as it worsens. Find out what the patient was doing at the time the symptom began. For example, severe breathlessness that wakes a patient from sleep is very suggestive of cardiac failure.

Associated symptoms

Here an attempt is made to uncover in a systematic way symptoms that might be expected to be associated with disease of a particular area. Initial and most thorough attention must be given to the system that includes the presenting complaint (see Questions box 1.1, page 9). Remember that while a single symptom may provide the clue that leads to the correct diagnosis, usually it is the combination of characteristic symptoms that most reliably suggests the diagnosis.

Questions box 1.1

The systems review

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous (alarm) problem.

Cardiovascular system

Respiratory system

Haematological system

Current treatment and drug allergies

Ask the patient whether he or she is currently taking any tablets or medicines (the use of the word ‘drug’ may cause alarm); the patient will often describe these by colour or size rather than by name and dose. Then ask the patient to show you all his or her medications, if possible, and list them. Note the dose, length of use, and the indication for each drug. This list may provide a useful clue to chronic or past illnesses, otherwise forgotten. Remember that some drugs are prescribed as transdermal patches or subcutaneous implants (e.g. contraceptives and hormonal treatment of carcinoma of the prostate). Ask whether the drugs were taken as prescribed. Always ask specifically whether a woman is taking the contraceptive pill, because this is not considered a medicine or tablet by many who take it. The same is true of inhalers, or what many patients call their ‘puffers’.

There may be some medications or treatments the patient has had in the past which remain relevant. These include corticosteroids, chemotherapeutic agents (anti-cancer drugs) and radiotherapy. Often patients, especially those with a chronic disease, are very well informed about their condition and their treatment. However, some allowance must be made for patients’ non-medical interpretation of what happened.10

Note any adverse reactions in the past. Also ask specifically about any allergy to drugs (often a skin reaction or episode of bronchospasm) and what the allergic reaction actually involved, to help judge if it was really an allergic reaction.12 The patient often confuses an allergy with a side-effect of a drug.

Menstrual history

For women, a menstrual history should be obtained; it is particularly relevant for a patient with abdominal pain, a suspected endocrine disease or genitourinary symptoms. Write down the date of the last menstrual period. Ask about the age at which menstruation began, if the periods are regular, or whether menopause has occurred. Ask if the symptoms are related to the periods. Do not forget to ask a woman of childbearing age if there is a possibility of pregnancy; this, for example, may preclude the use of certain investigations or drugs.13 Observing the well-known axiom that ‘every woman of childbearing years is pregnant until proven otherwise’ can prevent unnecessary danger to the unborn child and avoid embarrassment for the unwary clinician. Ask about any miscarriages. Record gravida (the number of pregnancies) and para (the number of births of babies over 20 weeks’ gestation).

The past history

Ask the patient whether he or she has had any serious illnesses, operations or admissions to hospital in the past. Don’t forget to inquire about childhood illnesses and any obstetric or gynaecological problems. Previous illnesses or operations may have a direct bearing on the current health of the patient. It is worth asking specifically about certain operations that have a continuing effect on the patient’s health; for example, operations for malignancy, bowel surgery or cardiac surgery—especially valve surgery. Implanted prostheses are common in surgical, orthopaedic and cardiac procedures. These may involve a risk of infection of the foreign body, while magnetic metals—especially cardiac pacemakers—are a contraindication to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Chronic kidney disease may be a contraindication to X-rays using iodine contrast materials and MRI scanning using gadolinium contrast. Pregnancy is usually a contraindication to radiation exposure (X-rays and nuclear scans—remember that CT scans cause hundreds of times the radiation exposure of simple X-rays).

The social and personal history

Smoking

Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for vascular disease, chronic lung disease, several cancers and peptic ulceration, and may damage the fetus (Table 1.2). Cigar and pipe smokers typically inhale less smoke than cigarette smokers, and overall mortality rates are correspondingly lower in this group, except from carcinoma of the oral cavity, larynx and oesophagus.

| 1 Cardiovascular disease |

* Individual risk is influenced by the duration, intensity and type of smoke exposure, as well as by genetic and other environmental factors. Passive smoking is also associated with respiratory disease.

Alcohol

Ask whether the patient drinks alcohol.14 If so, ask what type, how much and how often. If the patient claims to be a social drinker, find out exactly what this means. In a glass of wine, a nip (or shot) of spirits, a glass of port or sherry, or a 200 mL (7 oz) glass of beer, there are approximately 8–10 g of alcohol (1 unit = 8 g). In the UK, the current recommended safe limits are 21 units (168 g of ethanol) a week for men and 14 units (112 g of ethanol) for women; weekly consumption of more than 50 units for men and 35 units for women defines a high-risk group. Alcohol becomes a major risk factor for liver disease in men if more than 80 g and in women if more than 40 g are taken daily for 5 years or longer. The National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC) in Australia recommends a maximum alcohol intake of no more than 40 g per day for males on average (and 20 g per day for females) with two alcohol-free days a week. Alcoholics are notoriously unreliable about describing their alcohol intake, so it may be important to suspend belief and sometimes (with the patient’s permission) talk to the relatives.

Certain questions can be helpful in making a diagnosis of alcoholism; these are referred to as the CAGE questions:15

If the patient answers ‘yes’ to any of these questions, this suggests there may be a serious alcohol dependence problem. The complications of alcohol abuse are summarised in Table 1.3.

| Gastrointestinal system |

Occupation and education

Ask the patient about present occupation;16 the WHACS mnemonic is useful here:17

Finding out exactly what the patient does at work can be helpful (page 113). Note particularly any work exposure to dusts, chemicals or disease; for example, mine and industrial workers may have the disease asbestosis. Find out if any similar complaints have affected fellow workers.

The family history

Many diseases run in families. For example, ischaemic heart disease that has developed at a young age in parents or siblings is a major risk factor for ischaemic heart disease in the offspring. Various malignancies, such as breast and large-bowel carcinoma, are more common in certain families. Both genetic and common environmental exposures may explain these familial associations. Some diseases (e.g. haemophilia) are directly inherited.18

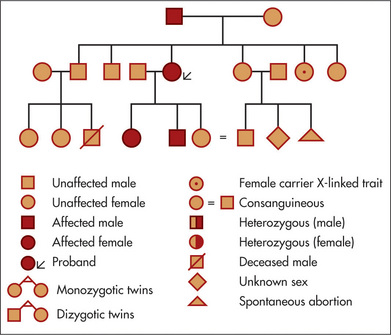

Ask about any history of a similar illness in the family. Inquire about the health and, if relevant, the causes of death and ages of death of the parents and siblings. If there is any suggestion of a hereditary disease, a complete family tree should be compiled showing all members affected (Figure 1.1). Patients can be reluctant to mention that they have relatives with mental illnesses, epilepsy or cancer, so ask tactfully about these diseases. Consanguinity (usually first cousins marrying) increases the probability of autosomal recessive abnormalities in the children; ask about this if the pedigree is suggestive.

Systems review

As well as detailed questioning about the system likely to be diseased, it is essential to ask about important symptoms and disorders in other systems (Questions box 1.1), otherwise important diseases may be missed.19,20 An experienced clinician will perform a targeted systems review, based on information already obtained from the patient; clearly it is not realistic to put all of the listed questions to a patient.

When recording the systems review, list important negative answers (‘relevant negatives’). Remember: if other recent symptoms are unmasked, more details must be sought; relevant information is then added to the history of the presenting illness. Before completing the history, it is often valuable to ask what the patient thinks is wrong, and what he or she is most concerned about. General and sympathetic questions about the effect of a chronic or severe illness on the patient’s life are important for establishing rapport and for finding out what else might be needed (both medical and non-medical) to help the patient.

Skills in history taking

In summary, several skills are important in obtaining a useful and accurate history.21 First, establish rapport and understanding. Second, ask questions in a logical sequence. Start with open-ended questions. Listen to the answers and adjust your interview accordingly. Third, observe and provide non-verbal clues carefully. Encouraging, sympathetic gestures and concentration on the patient that makes it clear he or she has your undivided attention are most important and helpful, but are really a form of normal politeness. Fourth, proper interpretation of the history is crucial.

Your aim should be to obtain information that will help establish the likely anatomical and physiological disturbances present, the aetiology of the presenting symptoms and the impact of the symptoms on the patient’s ability to function. (In Chapter 2, some advice on how to take the history in more challenging circumstances is considered.) This type of information will help you plan the diagnostic investigations and treatment, and to discuss the findings with, or present them to, a colleague if necessary (see page 462). First, however, a comprehensive and systematic physical examination is required.

These skills can be obtained and maintained only by practice.

1. Longson D. The clinical consultation. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1983;17:192-195. Outlines the principles of hypothesis generation and testing during the clinical evaluation

2. Nardone DA, Johnson GK, Faryna A, et al. A model for the diagnostic medical interview: nonverbal, verbal and cognitive assessments. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:437-442. Verbal and non-verbal questions and diagnostic reasoning are reviewed in this useful article

3. Bellet PS, Maloney MJ. The importance of empathy as an interviewing skill in medicine. JAMA. 1991;266:1831-1832. Distinguishes between empathy, reassurance and patient education

4. Brewin T. Primum non nocere? Lancet. 1994;344:1487-1488. Review of a key principle in clinical management

5. Platt FW, McMath JC. Clinical hypocompetence: the interview. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:898-902. A valuable review of potential flaws in interviewing, condensed into five syndromes: inadequate content, database flaws, defects in hypothesis generation, failure to obtain primary data and a controlling style

6. Coulehan JL, et al. ‘Tell me about yourself’: the patient-centred interview. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1079-1084.

7. Fogarty L, et al. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:371-379.

8. Barrier P, et al. Two words to improve physician–patient communication: What else? Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:211-214.

9. Blau JN. Time to let the patient speak. BMJ. 1999;298:39. The average doctor’s uninterrupted narrative with a patient lasts less than 2 minutes (and often much less!), which is too brief. Open interviewing is vital for accurate history taking

10. Smith RC, Hoppe RB. The patient’s story: integrating the patient- and physician-centered approaches to interviewing. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:470-477. Patients tell stories of their illness, integrating both the medical and psychosocial aspects. Both need to be obtained, and this article reviews ways to do this and to interpret the information

11. Beckman H, Markakis K, Suchman A, Frankel R. Getting the most from a 20-minute visit. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:662-664. A lot of information can be obtained from a patient even when time is limited, if the history is taken logically

12. Salkind AR, Cuddy PG, Foxworth JW. The rational clinical examination. Is this patient allergic to penicillin? An evidence-based analysis of the likelihood of penicillin allergy. JAMA. 2001;285(19):2498-2505.

13. Ramosaka EA, Sacchetti AD, Nepp M. Reliability of patient history in determining the possibility of pregnancy. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:48-50. One in ten women who denied the possibility of pregnancy, in this study, had a positive pregnancy test

14. Kitchens JM. Does this patient have an alcohol problem? JAMA. 1994;272:1782-1787. A useful guide to making this assessment

15. Beresford TP, Blow FC, Hill E, Singer K, Lucey MR. Comparison of CAGE questionnaire and computer-assisted laboratory profiles in screening for covert alcoholism. Lancet. 1990;336:482-485.

16. Newman LS. Occupational illness. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1128-1134. The importance of knowing the occupation for the diagnosis of an illness cannot be overemphasised

17. Blue AV, Chessman AW, Gilbert GE, Schuman SH, Mainous AG. Medical students’ abilities to take an occupational history: use of the WHACS mnemonic. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42(11):1050-1053.

18. Rich EC, Burke W, Heaton CJ, Haga S, Pinsky L, Short MP, Acheson L. Reconsidering the family history in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):273-280.

19. Hoffbrand BI. Away with the system review: a plea for parsimony. BMJ. 1989;198:817-819. Presents the case that the systems review approach is not valuable. A focused review still seems to be useful in practice (see below)

20. Boland BJ, Wollan PC, Silverstein MD. Review of systems, physical examination, and routine test for case-finding in ambulatory patients. Am J Med Sci. 1995;309:194-200. A systems review can identify unsuspected clinically important conditions

21. Simpson M, Buchman R, Stewart M, et al. Doctor–patient communication: the Toronto consensus statement. BMJ. 1991;303:1385-1387. Most complaints about doctors relate to failure of adequate communication. Encouraging patients to discuss their major concerns without interruption or premature closure enhances satisfaction and yet takes little time (average 90 seconds). Factors that improve communication include use of appropriate open-ended questions, giving frequent summaries, and the use of clarification and negotiation. Giving premature advice or reasurance, or inappropriate use of closed questions, badly affects the interview. These skills can be learned but require practice