The Gastrointestinal System

SYSTEMWIDE ELEMENTS

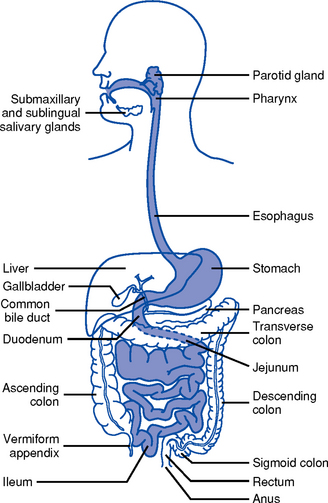

1. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract (Figure 8-1)

i. Lips, gums and teeth, and inner structures of the cheeks, tongue, hard and soft palate, and salivary glands

ii. Chewing prepares food by softening and moving it around, mixing it with saliva, and forming a bolus

iii. Skeletal muscles for chewing are coordinated by cranial nerves V, VII, IX, X, XI, XII

iv. Saliva aids in swallowing; approximately 570 ml/day of saliva is secreted. Submandibular, parotid, and sublingual salivary glands along with minor salivary glands in the oral mucosa secrete mixed saliva, which is 99% water and 1% solids, and includes electrolytes and organic protein molecules.

i. Extends from the cricoid cartilage to the level of the sixth cervical vertebra

ii. Swallowing receptors are stimulated by the autonomic nervous system when a food bolus moves toward the back of the mouth. The motor impulses to swallow are transmitted via cranial nerves V, IX, X, and XII.

i. Transports food from the mouth to the stomach and prevents retrograde movement of the stomach contents

ii. Collapsible tube about 25 cm long that lies posterior to the trachea and the heart

(a) Begins at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra and extends through the mediastinum and diaphragm to the level of the first thoracic vertebra, where it attaches to the stomach below the level of the diaphragm

(b) Upper portion of the esophagus is striated skeletal muscle, which is gradually replaced by smooth muscle so that the lower third of the esophagus is totally smooth muscle

(c) Motor and sensory impulses for swallowing and food passage derive from the vagus nerve. Lower esophagus also innervated by splanchnic and sympathetic neurons. Food moves by the strong muscular contraction of peristalsis and by gravity. In the absence of gravity, nutrients transported by muscular contractions.

(d) Sphincters: Hypopharyngeal (proximal) prevents air from entering the esophagus during inspiration; gastroesophageal (distal) prevents gastric reflux into the esophagus

(a) Arterial supply: Celiac trunk includes the gastric, pyloric, right, and left gastroepiploic arteries

(b) Venous drainage: Splanchnic bed drains the entire GI tract; gastric vein drains the stomach and esophagus

(c) Direct drainage into the azygous and hemiazygous veins of the mediastinum; all of these then drain into the portal vein

i. Food storage reservoir and site of the start of the digestive process. Normal capacity is 1000 to 1500 ml but can hold up to 6000 ml.

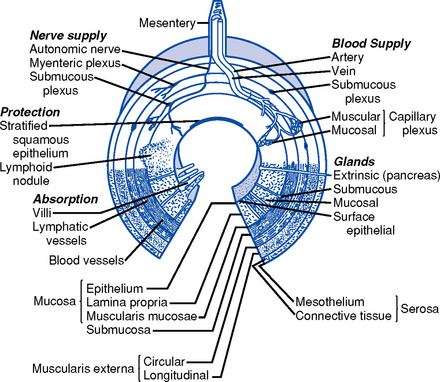

ii. Layers of the stomach and intestinal wall (Figure 8-2)

(a) Mucosa: Cells produce mucus that lubricates and protects the inner surface. These cells are replaced every 4 to 5 days. This layer receives the majority of the blood supply of the stomach.

(1) Epithelium: Contains the gastric, cardiac, fundic, and pyloric glands

a) Gastric cells: Contain microvilli that monitor intragastric pH

b) Cardiac glands: Secrete alkaline mucus, a lubricant that continually bathes and protects the epithelial lining from autodigestion

(2) Lamina propria: Contains lymphocytes; site of gut immunologic response

(b) Submucosa: Contains connective tissue and elastic fibers, blood vessels, nerves, lymphatic vessels, and structures responsible for secreting digestive enzymes

(c) Circular and longitudinal smooth muscle layers: Continue the modification of food into a liquid consistency and move it along the GI tract. Movements are tonic and rhythmic, occurring every 20 seconds. Electrical activity is constantly present in the smooth muscle layers.

(1) Hormone secreted in response to distention of antrum or fundus by food

(2) Stimulates secretion of hydrochloric acid by the parietal cells and secretion of pepsin by chief cells

(b) Histamine: Hormone secreted by mast cells in the presence of food that is critical to the regulation of gastric acid secretions

(a) Is proportional to the volume of material in the stomach

(b) Depends on the character of the ingested material: Liquids, digestible solids, fats, indigestible solids

(c) Factors accelerating gastric emptying: Large volume of liquids; anger; insulin

(d) Factors inhibiting gastric emptying: Fat, protein, starch, sadness, duodenal hormones

(1) Coordinated by the vomiting center in the medulla in response to afferent impulses from various regions of the body

(2) Stimuli that induce vomiting: Tactile stimulation to the back of the throat, increased intracranial pressure (ICP), intense pain, dizziness, anxiety

(3) Autonomic nervous system discharge may precede vomiting: Sweating, increased heart rate, increased salivation, nausea, muscular force by the diaphragm and abdomen

(a) Arterial: Celiac artery flows into the right gastric artery, left gastric artery, gastroduodenal artery, and finally into the right gastroepiploic artery; the splenic artery flows into the left gastroepiploic artery

(b) Venous drainage: Splanchnic bed drains the entire GI tract, the gastric vein drains the stomach and esophagus; both vessels drain into the portal vein

(a) Intrinsic nervous system (intramural neurons) within the wall of the GI tract is independent of central nervous system controls

(1) Myenteric (Auerbach’s) plexus: Located between the circular and longitudinal muscles; stimulation increases muscle tone, contractions, velocity, and excitation of the digestive tract

(2) Submucosal (Meissner’s) plexus: Located between the circular and submucosal layers; influences secretions of the digestive tract; contains secretomotor and enteric vasodilator neurons

(b) Extrinsic system: Via the central nervous system, parasympathetic system, and sympathetic system

(1) Parasympathetic: Fibers arise from the medulla and spinal segments (i.e., vagus nerves)

a) Cranial segments: Transmission via the vagus nerve; innervate the stomach, pancreas, and first half of the small intestine

b) Sacral segments: Innervate the distal half of the large intestine, sigmoid, rectum, and anus

c) Enhances function of the intrinsic nervous system and the secretion of acetylcholine

d) Increases glandular secretion and muscle tone; decreases sphincter tone

(2) Sympathetic: Motor and sensory fibers arise from the thoracic and lumbar segments; distribution is via the sympathetic ganglia (i.e., celiac plexus)

2. Middle GI tract: Small intestine

a. Approximately 5 m long; extends from the pylorus to the ileocecal valve

b. Consists of three divisions: Duodenum, jejunum, ileum

c. Primary function is absorption of nutrients

d. Layers of the intestinal wall (Figure 8-2)

i. Mucosa: Innermost layer; receives the majority of the blood supply; the predominant site of nutrient absorption

(a) Epithelium: Covered with villi and microvilli that increase the surface area of the small intestine several hundred times; contain glands, crypts of Lieberkühn (intestinal glands) that secrete approximately 2 L of fluid every 24 hours and goblet cells that secrete mucus

(b) Lamina propria: Contains lymphocytes; site of gut immunologic responsiveness

ii. Submucosa: Contains loose connective tissue and elastic fibers, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves

iii. Muscularis: Muscle layer; function is involuntary and involved in motility

iv. Serosa: Outermost layer; protects and suspends intestine within the abdominal cavity

e. Peristalsis: Propulsive movements that move the intestinal contents toward the anus. Approximately 3 to 5 hours is necessary for passage through the entire small intestine.

i. Arterial: Derived from the celiac artery (first portion of the duodenum) and the superior mesenteric arteries (remainder of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum)

ii. Venous drainage: Splanchnic bed drains the entire GI tract

g. Innervation: Same as for stomach

h. Small intestine digestive enzymes not secreted, but integral components of the mucosa

i. Bile and pancreatic enzymes are secreted into the duodenum

ii. In the jejunum and the ileum, food is digested and absorbed

iii. Up to 3000 ml/day of digestive enzymes (e.g., lipase, amylase, maltase, and lactase)

i. Secretin: Secreted by the mucosa of the duodenum in response to acidic gastric juice from the stomach and to alcohol ingestion

(a) Augments the action of cholecystokinin (CCK)

(b) Stimulates release of the alkaline component of pancreatic juice and the secretion of water

ii. CCK: Secreted by the mucosa of the jejunum in response to the presence of fat, protein, and acidic contents in the intestine

(a) Increases contractility and emptying of the gallbladder and blocks the increased gastric motility caused by gastrin

(b) Stimulates secretion of pancreatic digestive enzymes, bicarbonate, and insulin

iii. Gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP): Secreted by the mucosa of the upper portion of the small intestine in response to the presence of carbohydrates and fat in the intestine; inhibits gastric acid secretion and motility, slowing the rate of gastric emptying

iv. Vasoactive intestinal peptide: Secreted throughout the gut in response to acidic gastric juice in the duodenum

(a) Main effects are similar to those of secretin

(b) Stimulates the secretion of intestinal juices to decrease the acidity of chyme and inhibits gastric secretion

v. Somatostatin: Secreted throughout the intestine in response to vagal stimulation, ingestion of food, and release of CCK, GIP, glucagon, and secretin

(a) Inhibits the secretion of saliva, gastric acid, pepsin, intrinsic factor, and pancreatic enzymes

(b) Inhibits gastric motility, gallbladder contraction, intestinal motility, and blood flow to the liver and intestine

vi. Serotonin: Secreted throughout the intestine in response to vagal stimulation, increased luminal pressure, and the presence of acid or fat in the duodenum; inhibits gastric acid secretion and mucin production

j. Functions: Almost all absorption occurs in the small intestine via four mechanisms: Active transport, passive diffusion, facilitated diffusion, and nonionic transport

i. Vitamins are absorbed primarily in the intestine by passive diffusion, except for the fat-soluble vitamins, which require bile salts for absorption, and vitamin B12, which requires intrinsic factor

ii. Water absorption: Approximately 8 L of water per day is absorbed by the small intestine

iii. Electrolyte absorption: Most occurs in the proximal small intestine

iv. Iron absorption: Absorbed in the ferrous form in the duodenum

v. Carbohydrate absorption: Complex carbohydrates are broken down into monosaccharides or basic sugars (fructose, glucose, galactose) by specific enzymes (e.g., amylase, maltase)

vi. Protein absorption: Protein is broken down into amino acids and small peptides; essential amino acids are lysine, phenylalanine, isoleucine, valine, methionine, leucine, threonine, and tryptophan

i. Approximately 6.5 cm in diameter and 1.5 m long; extends from terminal ileum at the ileocecal valve to the rectum

ii. Ileocecal valve: Prevents return of feces from the cecum into the ileum

i. Cecum: Blind pouch to which the appendix is attached; about 2.5 cm from the ileocecal valve

ii. Ascending colon: Extends from the cecum to the lower border of the liver, where it forms the right hepatic flexure

iii. Transverse colon: Crosses the upper half the abdominal cavity, curving downward at the lower end of the spleen at the left colonic (splenic) flexure anterior to the small intestine

iv. Descending colon: Extends from the splenic flexure to the sigmoid colon

v. Sigmoid colon: S-shaped curve extending from the descending colon to the rectum

c. Layers of the large intestine wall (Figure 8-2): No villi and no secretion of digestive enzymes. Layers similar to those of the middle GI tract with exceptions:

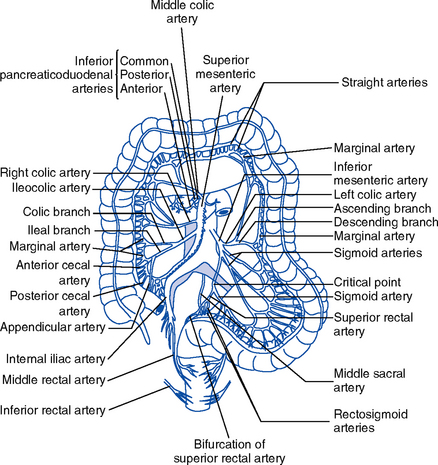

(a) Superior mesenteric artery supplies the ascending colon and part of the transverse colon

(b) Inferior mesenteric artery feeds the transverse colon, sigmoid colon, and upper rectum

(c) Hypogastric arteries give rise to the middle and inferior rectal and hemorrhoidal arteries

(d) Rectal arteries, which arise from the internal iliac arteries, supply the distal rectum

i. Absorption of water and electrolytes: Approximately 500 ml of chyme (the byproduct of digestion) enters the colon per day and, of this, 400 ml of water and electrolytes are reabsorbed

ii. Breakdown of cellulose by enteric bacteria

iii. Synthesis of vitamins (folic acid, vitamin K, riboflavin, nicotinic acid) by enteric bacteria

iv. Storage of fecal mass until it can be expelled from the body

(a) Takes approximately 18 hours from the time food enters the colon until the intestinal contents reach the distal portion of the colon

(b) Time from ingestion of food to defecation of the residue may be 24 hours or longer

(a) Peristalsis: Propulsive movements that push GI contents toward the anus

(b) Haustral churning is the major type of movement in the colon

(c) Factors that enhance motility: Bacterial enterotoxins, viral infections of the gut, regional enteritis, ulcerative colitis, increased bile salts, osmotic overload, laxatives

(d) Factors that inhibit motility: Low-bulk diet, parenteral nutrition, bed rest, dehydration, ileus, fasting, drugs

(e) Poor motility causes more absorption, and the development of hard feces in the transverse colon causes constipation

(f) Aging causes a reduction in peristalsis and decreased GI motility throughout the GI system

f. Innervation: Same as for the stomach and small intestine

i. The gut encounters a variety of potentially harmful substances daily; these can include natural toxins in food, insecticides, preservatives, chemical waste products, and airborne particulate matter that is swallowed.

ii. Mechanisms exist within the GI tract to protect the integrity of the gut and thus the individual

iii. Fluid and cellular layers

(a) Aqueous layer: Stationary layer immediately adjacent to the microvillus border of the enterocytes; consists of acids, digestive enzymes, and bacteria depending on the location in GI lumen

(b) Mucosal barrier: Physical and chemical barriers that protect the wall of the gut from harmful substances. Surfaces of the stomach, intestine, biliary and pancreatic ducts, and gallbladder have cells that synthesize and release mucus.

(c) Epithelial cells: Tight junctions between cells regulated by hormones and cytokines make them relatively impervious to large molecules and bacteria; rapid proliferation of cells minimizes the adherence of flora. The level of permeability varies within the various segments of the GI tract.

(d) Mucus-bicarbonate barrier: Forms a layer of alkalinity between the epithelium and luminal acids that neutralizes the pH and protects against surface shear

iv. Motility: Prevents bacteria in the distal small intestine from migrating proximally into the sterile parts of the upper GI system

(1) Expulsion of toxic substances as a result of stimulation of the vomiting center in the medulla

(2) Barrier against the reflux of duodenal contents back into the stomach

(b) Colon: Moves pathogens and potential carcinogens out of the body

v. Gut immunity: Necessary because the gut is a reservoir of potentially pathogenic bacteria

(a) B lymphocytes that bear surface immunoglobulin A (IgA) or synthesize secretory IgA that prevents antigens from binding to mucous cells

vi. Gastric acid: Intragastric pH below 4.0 is essential

vii. Commensal bacteria: Natural gut flora are stable and protective in a healthy person by competing with pathogenic species for nutrients and attachment sites, and produce inhibitory substances against pathogenic species

(a) Stomach, duodenum, and jejunum are sterile

(b) Ileum contains aerobic and anaerobic bacteria: Dietary intake is a major factor in determining intestinal flora

(c) Large intestine contains large numbers of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, and smaller numbers of yeast and fungi

viii. Impaired gut barrier function facilitates bacterial translocation, which is the egress of bacteria and/or their toxins across the mucosal barrier and into the lymphatic vessels and portal circulation

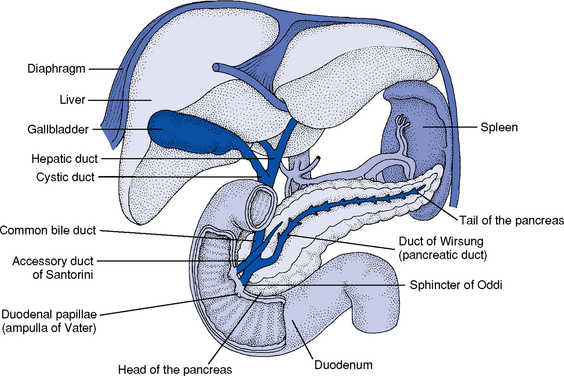

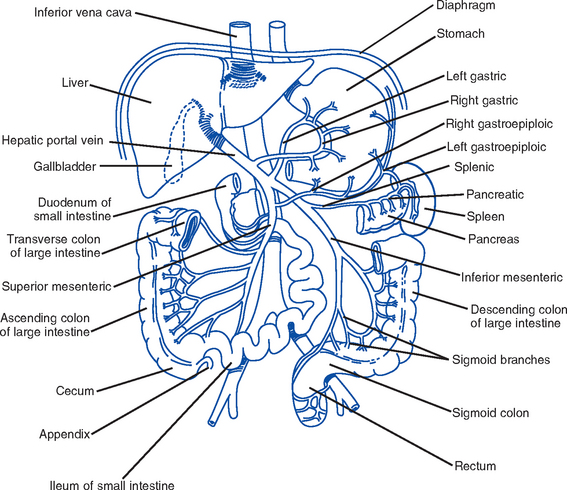

4. Accessory organs of digestion (Figure 8-4)

i. Largest solid organ, weighing approximately 3 lb (1500 g), located in the right upper quadrant, beneath the diaphragm

ii. Consists of three lobes divided into eight independent segments, each of which has its own vascular inflow, outflow, and biliary drainage. Because of this division into self-contained units, each can be resected without damaging those remaining.

(a) Right lobe: Anterior (segments V and VIII) and posterior (segments VI and VII)

(b) Left lobe: Medial (segment IV) and lateral (segments II and III); the left lobe extends across the midline into the left upper quadrant

iii. Microscopically the liver consists of functional units called lobules composed of portal triads in which the bile ducts, hepatocytes, and artery are located. The portal triads are then bounded by sinusoids and a central vein. A cross section of a classic lobule or acinus is hexagonal.

iv. Blood supply (Figure 8-5): Derived from both a vein and an artery

(a) 25% of cardiac output flows through the liver per minute

(b) Portal vein (after draining the mesenteric veins and pancreatic and splenic veins) and hepatic artery (off the aorta via the celiac trunk) enter the liver at the porta hepatis or hilum (a horizontal fissure in the liver, containing blood and lymph vessels, nerves, and the hepatic ducts)

(c) 75% is supplied by the portal vein; each segment receives a branch of the portal vein and 25% is supplied by the hepatic artery

(d) Small branches of each of these vessels enter the acinus at the portal triad (an area in the liver consisting of the portal vein, branches of the hepatic artery, and tributaries to the bile duct

(e) Functionally, the liver can be divided into three zones, based on oxygen supply. Zone 1 encircles the portal tracts where the oxygenated blood from hepatic arteries enters. Zone 3 is located around the central veins, where oxygenation is poor. Zone 2 is located in between.

(f) Blood from both the portal vein and the hepatic artery mixes together in the hepatic sinusoids and then flows through the sinusoids to the hepatic venules (zone 3) through the central veins, branches of the hepatic vein

(1) Found between plates (layers) of hepatocytes; have a porous lining with fenestrations that allows nutrients in the blood plasma to wash freely over exposed surfaces (the spaces of Disse)

(2) Sinusoidal lining consists of endothelial cells, Kupffer cells, perisinusoidal fat-storing cells, and pit cells.

(h) Venous drainage: Begins in the central veins in the center of the lobules; central veins empty into the hepatic veins, which empty into the inferior vena cava

v. Biliary duct system for draining bile

(a) Begins at the sinusoidal level as bile canaliculi, which branch into ductules, intralobular bile ducts, and larger intrahepatic ducts

(b) Intrahepatic ducts come together at the porta hepatis to form the common hepatic duct, which becomes the common bile duct after joining with the cystic duct and drains into the duodenum

vi. Physiology: The liver is a metabolically complex organ with interrelated digestive, metabolic, exocrine, hematologic, and excretory functions. The many functions it performs are interwoven; each lobe is an independent functional unit, so that up to 80% of the liver can be destroyed and it will regenerate.

(a) Digestive functions: Plays a role in the synthesis, metabolism, and transport of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins

(1) Carbohydrates: Maintains normal serum glucose levels by

a) Glycogen storage: Approximately 900 kcal of glycogen reserves are stored in the adult liver

b) Glycogenesis: Conversion of excess carbohydrates to glycogen for storage in the liver as a metabolic reserve

c) Glycogenolysis: Conversion of large stores of glycogen in muscles and liver to glucose

d) Gluconeogenesis: Manufacture of glucose from noncarbohydrate substrate (fat, fatty acids, glycerol, amino acids)

a) Bile secretion for fat digestion plays a role in fat and lipid synthesis, metabolism, and transport

b) Principal site of synthesis and degradation of lipids (cholesterol, phospholipids, lipoprotein): Produces approximately 1000 mg of cholesterol per day

c) Exogenous lipoprotein metabolism

d) Endogenous lipoprotein metabolism: Major lipoprotein synthesized by the liver is very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL); one third of VLDL remnants are converted to low-density lipoprotein (LDL)

e) Conversion of excess carbohydrate to triglyceride, which is stored as adipose tissue

f) Conversion of triglyceride to glycerol and fatty acids for energy

g) Storage of triglyceride and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K)

h) Storage of fats, cholesterol, proteins, vitamin B12, and minerals

a) Production of plasma proteins (albumin, prealbumin, transferrin, clotting factors, haptoglobin, ceruloplasmin, α1-antitrypsin, complement, α-fetoprotein)

b) Deamination: Metabolism of amino acids

c) Transamination: Conversion of amino acids to ammonia, conversion of ammonia to urea for urinary excretion

(b) Endocrine functions: Metabolism of glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, hormones

(d) Hematologic functions: Synthesis of bilirubin, coagulation factors

b. Gallbladder: Pear-shaped saclike organ that serves as a reservoir for bile

i. Attached to the inferior surface of the liver in the area that divides the right and left lobes (gallbladder fossa)

ii. Approximately 7 to 10 cm long; holds and concentrates approximately 30 ml of bile

iii. Blood supply: Arterial blood supply is from the cystic artery; venous drainage is via a network of small veins.

iv. Innervation: Splanchnic nerve, right branch of the vagus nerve

v. Cystic duct attaches the gallbladder to the common hepatic duct

(a) Union of the cystic duct and the common hepatic duct forms the common bile duct

(b) Common bile duct either joins the pancreatic duct outside the duodenum or forms a common channel through the duodenal wall at the ampulla of Vater

(c) Intraduodenal segment of the common bile duct and the ampulla is the sphincter of Oddi

vi. Presence of CCK in the blood (in response to chyme in the duodenum)

vii. Bile is composed of water, bile salts, and bile pigments

(a) Bile salts are responsible for the absorption and emulsification of fat and fat-soluble vitamins

(b) Bile pigments: High in cholesterol and phospholipids, give feces a brown color

(c) Bilirubin is the major bile pigment; it is a breakdown product of hemoglobin metabolism from senescent red blood cells

(1) Total: Indirect bilirubin plus direct bilirubin; when total bilirubin level is elevated and the cause is unknown, indirect and direct bilirubin fractions can be measured

(2) Indirect (unconjugated): Bilirubin bound to albumin before it binds to glucuronic acid; fat soluble. Causes of elevation of indirect bilirubin concentration in serum include the following:

a) Any hemolytic process (e.g., ABO mismatch in blood transfusion, β-hemolytic streptococcal infection)

b) Gilbert’s syndrome, a common disorder characterized by a mild, chronic fluctuating increase in the level of unconjugated bilirubin

c) Inherited deficiency of bilirubin, which results in variations of the Crigler-Najjar syndrome

(3) Direct (conjugated): Bilirubin bound to glucuronic acid, water soluble; concentration elevates with biliary tract obstruction (except cystic duct), diffuse biliary tract damage, acute cellular rejection after liver transplantation. Causes of elevation of direct bilirubin concentration in serum include the following:

a) Bile duct obstruction (e.g., stones, tumor, biliary stricture after liver transplantation)

c) Necrosis of the bile duct (e.g., hepatic artery thrombosis)

d) Autoimmune diseases of biliary stasis (e.g., primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis)

e) Inherited disorders of conjugated bilirubin excretion (e.g., Dubin-Johnson syndrome, Rotor’s syndrome)

c. Pancreas: Soft, flattened gland with a lobular structure but without an external capsule

i. 12 to 20 cm long, located in the retroperitoneal area

ii. Head lies in the C-shaped curve of the duodenum at the level of the body of L2

iii. Body extends horizontally behind the stomach

iv. Tail is contiguous with the spleen, lying between the two layers of the peritoneum that form the lienorenal ligament at the level of the body of L1

(a) Arterial blood supplies from the celiac axis, which divides into the common hepatic, splenic, and left gastric arteries and the superior mesenteric artery

(b) Venous drainage via the portal vein, which is formed by the joining together of the superior mesenteric and splenic veins

(a) Sympathetic efferent innervations via the greater, lesser, and least splanchnic nerves have an inhibitory function

(b) Parasympathetic innervation via the vagal nerves, which stimulate exocrine secretion

vii. Duct of Wirsung: Main pancreatic duct whose terminal end, the sphincter of Oddi in the ampulla of Vater, empties into the duodenum; shares the sphincter of Oddi with the common bile duct

viii. Duct of Santorini: Accessory pancreatic duct (present in 40% to 70% of persons) that lies anterior and opens into the second part of the duodenum proximal to the duct of Wirsung

ix. Pancreatic secretions: Consist of aqueous and enzymatic components

(1) Acinar cells (part of the exocrine function of the pancreas) secrete the pancreatic enzymes

(2) Amylase (for digestion of starches) and lipase (for digestion of fats) are secreted as active enzymes

(3) Pancreatic proteases are secreted as inactive precursors and are converted to active enzymes in the lumen of the small intestine (for digestion of proteins)

x. Food in the intestine stimulates the secretion of enzymes. Changes in the proportions of various nutrients in the diet result in changes in the proportions of enzymes in the pancreatic secretions. Adaptation of the pancreatic secretions is accomplished by hormones that operate at the level of gene expression:

(a) GIP and secretin increase the expression of the lipase gene

(b) CCK increases the expression of the protease genes

(c) In diabetic individuals, insulin regulates the expression of the amylase gene; however, how amylase expression is normally regulated in nondiabetic individuals is unknown

(d) Certain conditions decrease pancreatic secretion: Pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, tumors, and protein deficiency

xi. Endocrine cells found in the islets of Langerhans

(a) Alpha cells secrete glucagon, which is responsible for glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis

(b) Beta cells secrete insulin, which facilitates the use of glucose by tissues

(c) Delta cells secrete somatostatin, which inhibits the secretion of insulin, glucagon, and growth hormone

(d) Polypeptide cells are associated with the hypermotility of the GI tract and diarrhea

Patient Assessment

ii. History of present illness

iii. Past medical conditions (e.g., neurologic conditions, cirrhosis, diabetes), eating disorders, or communicable diseases (e.g., viral hepatitis, jaundice)

iv. Surgical history (e.g., appendectomy, gastric bypass)

vi. Pain: Location, duration, character, severity, alleviating and aggravating factors, relationship to changes in eating, bowel habits, or position

vii. Oral health status: Teeth, gums, tongue, pharynx

viii. Nausea or vomiting: Duration, alleviating and aggravating factors, description of vomitus (undigested food, unrecognizable digested product, blood—bright red or resembling coffee grounds), timing, and relationship to pain

ix. Loss of appetite (loss of desire or interest in food), duration, association with other symptoms

x. Dysphagia: Difficulty in swallowing, types of foods and/or liquids causing difficulty

xi. Heartburn (dyspepsia, reflux): Duration, alleviating and aggravating factors

xii. Fecal elimination: Diarrhea or constipation, color of stools, presence of blood (black, maroon, or bright red color); clay-colored stool—absence of bile pigment as a result of biliary obstruction or advanced cirrhosis

xiii. Urinary elimination: Color of urine; dark (tea-colored) urine—acute hepatocellular necrosis or severe biliary obstruction

xvii. Muscle wasting, atrophy: Wasting of the muscle over the temporal bones in the face or the thenar muscle of the thumb

i. Carcinoma, liver disease, pancreatitis, peptic ulcer disease

ii. Diabetes mellitus, anemia, tuberculosis

iii. Inflammatory bowel disease: Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis

i. Substance abuse: Tobacco use, alcohol use, drug use

ii. Sexual history: Heterosexual, homosexual relationships; involvement with prostitutes

d. Medication history (all medications evaluated but specifically herbal supplements, vitamins, anabolic steroids, motility agents, antacids, histamine or proton pump inhibitors, anticholinergics, antibiotics, antidiarrheals, laxatives, enemas, narcotics, sedatives, barbiturates, stimulants, antihypertensives, diuretics, anticoagulants, analgesics, nonsteroidal, steroids, chemotherapy agents)

2. Nursing examination of patient

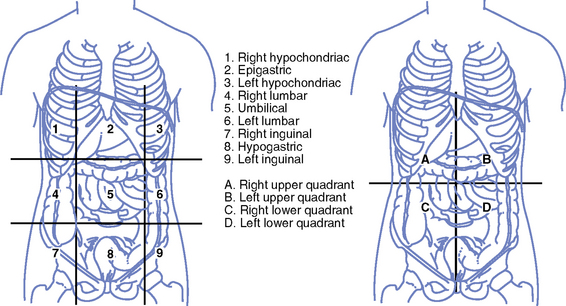

(a) Anatomic landmarks are used to locate and describe normal and abnormal assessment findings

(1) Xiphoid process, subcostal margins, costovertebral angle

(2) Abdominal quadrants (Figure 8-6), midline of abdomen

(3) Umbilicus, rectus abdominus muscle

(4) Anterior superior iliac spine, symphysis pubis, inguinal ligament

(b) General appearance: Physical signs of altered nutritional status (e.g., cachexia, obesity)

(c) Oral cavity: Gingivitis, lesions (e.g., herpes simplex, Candida albicans, leukoplakia), ability to swallow, presence of odors (e.g., ketones, fetor, alcohol)

(d) Abdominal profile: Evaluate with the patient lying supine on the examination table or bed

(1) Symmetry, size (girth), and contour of the abdomen from the costal margins to the symphysis pubis (flat, rounded, scaphoid, protuberant)

a) Abdominal distention can be due to fluid, fat, flatus, fetus, feces, malignancies, nonmalignant tumors

b) Asymmetry can be due to these causes as well as to obstructions, cysts, or scoliosis

(2) Condition of umbilicus (protruding; nodular; inverted; with calculus, ecchymoses, or drainage)

(3) Caput medusa: Engorged abdominal veins around the umbilicus are seen in patients with portal hypertension or obstruction of the superior or inferior vena cava

(4) Collateral vessels that come to the skin surface and traverse the abdomen: Seen in obesity and ascites

(5) Masses, visible peristalsis or pulsations

(6) Striae, ecchymoses, hematomas, scars, wounds, stomas, hernias, engorged veins, diastasis recti, fistulas, tubes, or drains

(7) Spider angiomas: Found above the umbilicus on the anterior and posterior thorax, head, neck, and arms

ii. Auscultation: Performed in all quadrants before percussion and palpation to note location and characteristics of bowel and other sounds

(a) Normal bowel sounds: Low-pitched, continuous gurgles heard in abdominal quadrants

(1) Factors related to hypoactive or absent sounds: Peritonitis, paralytic ileus, anesthesia, inflammation, electrolyte imbalance, gastric or intraabdominal bleeding, pneumonia, both mechanical and nonmechanical obstruction

(2) Factors related to hyperactive sounds: Hyperkalemia, gastroenteritis, gastric or esophageal bleeding, diarrhea, laxative use, mechanical obstruction

(c) Bruit: Denotes increased turbulence or significant dilatation

(1) Aortic bruit can be heard 2 to 3 cm above the umbilicus in the epigastric area and denotes partial aortic occlusion

(2) Hepatic bruit can be heard over the liver and may indicate primary liver cancer, alcoholic hepatitis, or vascular liver metastases

(3) Renal artery bruit can be heard to the left and/or right of midline in the epigastric areas in renal artery stenosis

(4) Iliac artery bruit can be heard in the left and/or right inguinal areas

(5) Venous hum or murmur heard over the liver denotes liver disease such as alcoholic hepatitis, hemangiomas, or dilated periumbilical circulation

(6) Friction rub over the spleen denotes inflammation or infarction of the spleen

(7) Peritoneal friction rub indicates peritoneal irritation

(8) Hepatic friction rub over the liver can be heard in cases of abscess and various types of hepatitis (e.g., syphilitic)

(1) Tympany is noted when percussing air-filled organs such as the stomach

(2) Resonance is noted when striking air-filled lungs

(3) Dullness is noted over solid organs such as the liver or spleen

(b) Percussion to evaluate the sizes of the liver and spleen

(1) Liver size can be estimated by percussing from the right clavicle straight down the right midclavicular line to detect changes in percussion tones

a) Beginning at the midclavicular line below the umbilicus, percuss for the lower edge of the liver. Over the bowel, the percussion tone is tympanic and transitions to dull, which denotes the lower edge of the liver.

b) At the level of the fifth intercostal space, percuss downward. The percussion tone transitions from the resonance of the lung tissue to dull, which denotes the upper edge of the liver.

c) Distance between the upper and lower edges of the liver at the midclavicular line is normally about 12 cm. A span of greater than 12 cm or less than 6 cm is abnormal. Gas in the colon, pregnancy, or tumors can impair accurate assessment of the liver span.

(2) Spleen can be percussed (dull tones) only if grossly enlarged (e.g., portal hypertension) at the left midclavicular line below the left costal margin. To determine the presence of masses or abnormal fluid (ascites) and air collections:

a) Collections can be confirmed by shifting dullness (fluid remains dependent with changes in position)

b) Fluid waves can be elicited by placing the hands on either side of the abdomen, then tapping one hand against the abdomen and feeling the wave transmitted to the opposite hand

c) Difference between fluid and fat can be determined by placing the hands on either side of the abdomen, having an assistant place his or her hand on the midline, and then pressing downward with one hand. Transmission of fat waves will be halted by the center hand, whereas fluid waves will continue toward the opposite hand.

(a) Light and deep palpation are done to determine the tone of the abdominal wall (relaxed, tense, rigid), areas of tenderness or pain, and the presence and characteristics of masses. Light palpation is done prior to deep palpation to determine areas of tenderness or resistance (guarding); observe the patient’s face for nonverbal signs of discomfort.

(b) Visceral tenderness: Dull, poorly localized (e.g., bowel obstruction)

(c) Somatic tenderness: Sharp, well localized (e.g., late appendicitis, capsular stretching of the swollen liver)

(d) Rebound tenderness: Occurs when palpation is suddenly withdrawn; associated with peritonitis

(e) Contralateral tenderness: Tenderness on the side opposite palpation (e.g., early appendicitis)

(f) Referred tenderness: Tenderness in an area distant from the source (e.g., right shoulder blade pain referred from the gallbladder)

(g) Murphy’s sign: Severe right upper quadrant tenderness elicited on deep palpation under the right costal margin, exacerbated by deep inspiration and associated with cholecystitis

(h) To determine liver size: Palpate at the patient’s right side

(1) Right flank area is supported with the left hand and the fingertips of the right hand are slid under the right costal margin, using firm pressure

(2) Fingertips are advanced as the patient inhales deeply and the liver edge moves 1 to 3 cm downward

(3) Fingertips are held steady as the patient exhales and inhales again, and the smooth (normal) edge of the liver may be felt moving past the fingertips

(4) The liver is not normally palpated more than 1 to 2 cm below the right costal margin (in cases of alcoholic liver disease or fatty liver disease, the liver may be enlarged with the margins projecting down into the abdomen 4 to 5 cm)

(i) To determine spleen size: Palpate from the patient’s right side

(1) Left flank area is supported with the right hand and the fingertips of the left hand are slid under the left costal margin, using firm pressure

(2) Fingertips are advanced as the patient inhales deeply and the spleen edge moves 1 to 3 cm downward

(3) Fingertips are held steady as the patient exhales and inhales again, and the smooth (normal) edge of the spleen may be felt moving past the fingertips

(4) The spleen is not normally palpable, except in cases of enlargement or inferior displacement

3. Appraisal of patient characteristics: Patients in critical care units with acute GI problems have conditions that vary in complexity. During their hospitalization their clinical status may move along the continuum of care from improvement to deterioration in a nonlinear fashion. This potential for gradual or abrupt changes in clinical condition with possibly life-altering effects creates barriers in the ability to monitor life sustaining functions with precision. Clinical attributes of patients with acute GI disorders that the nurse needs to assess include the following:

i. Level 1—Minimally resilient: A 24-year-old female college student admitted in fulminant liver failure due to autoimmune hepatitis with encephalopathy, coagulopathy, and acute renal failure

ii. Level 3—Moderately resilient: A 68-year-old male accountant with a ruptured appendix who develops sepsis and acute renal failure

iii. Level 5—Highly resilient: A 16-year-old male high school student with blunt abdominal trauma after a motor vehicle accident. He was wearing a seatbelt and the vehicle air bags deployed.

i. Level 1—Highly vulnerable: A 45-year-old female diagnosed with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis who experiences an esophageal variceal hemorrhage during hospitalization

ii. Level 3—Moderately vulnerable: A 56-year-old attorney with acute pancreatitis, high fever, and positive blood culture results, which indicate septicemia

iii. Level 5—Minimally vulnerable: A 24-year-old Chinese male with acute hepatitis B viremia

i. Level 1—Minimally stable: An 84-year-old male who came to the emergency department with a ruptured aortic aneurysm and develops a bowel ischemia following surgery to repair his aorta

ii. Level 3—Moderately stable: A 62-year-old newly retired male with colon cancer who is undergoing chemotherapy after tumor resection

iii. Level 5—Highly stable: A 45-year-old homemaker who has undergone a cholecystectomy for gallstones and had no prior health problems

i. Level 1—Highly complex: A 36-year-old grocery store clerk with cirrhosis and newly diagnosed liver cancer who is listed for liver transplantation shortly after separating from his wife and moving back in with his parents

ii. Level 3—Moderately complex: An 18-year-old male who suffered abdominal trauma in a motor vehicle accident that killed his girlfriend

iii. Level 5—Minimally complex: A 34-year-old married mechanic after small bowel resection for Crohn’s disease

i. Level 1—Few resources: An illiterate 78-year-old widower with no children who has a small bowel obstruction due to cancer and has minimal income, has no transportation, and cannot afford his medications or insurance copayment

ii. Level 3—Moderate resources: A 48-year-old field worker with cirrhosis with decompensations of encephalopathy and ascites who has a 17-year-old son. He has medical and Supplemental Security Income disability benefits that will cover the cost of medications.

iii. Level 5—Many resources: A 58-year-old college professor, who is married with three grown children who live locally and who has chronic hepatitis C cirrhosis

i. Level 1—No participation: A 51-year-old migrant field worker with no known family in the United States who has encephalopathy from fulminant liver failure due to exposure to agricultural chemicals

ii. Level 3—Moderate level of participation: A 68-year-old widow being discharged following an upper GI bleed from a peptic ulcer. She underwent gastric resection and her primary caregiver will be her daughter.

iii. Level 5—Full participation: A 25-year-old secretary with a mild episode of pancreatitis, recovering without complications and planning her follow-up care with her husband and a good family friend who is a nurse

g. Participation in decision making

i. Level 1—No participation: A 98-year-old female with Alzheimer’s disease who has no family and who has been in a motor vehicle accident with severe abdominal injuries, renal failure, and sepsis

ii. Level 3—Moderate level of participation: A 45-year-old businessman, married with two young children, who has esophageal cancer and is undergoing esophageal resection followed by chemotherapy. The patient and his wife are overwhelmed by the changes in their lives and unsure of what the treatment options and posthospitalization issues are.

iii. Level 5—Full participation: A 34-year-old tennis coach with severe gastroenteritis that resolved after 2 days in the hospital who is planning to continue his recovery using vacation time

i. Level 1—Not predictable: A 43-year-old health food store manager who suddenly develops jaundice, elevated liver enzyme levels, and encephalopathy with no prior history or risk factors for liver disease

ii. Level 3—Moderately predictable: A 34-year-old Vietnamese general manager with jaundice, abnormal liver test results, malaise, and hepatosplenomegaly after returning from a trip to South America

iii. Level 5—Highly predictable: A 40-year-old store manager who recently underwent liver transplantation and is progressing well toward discharge

ii. Serum electrolyte, glucose, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, calcium, magnesium, ammonia, and cholesterol levels

iii. Liver function tests: Total protein, albumin, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT; formerly serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase [SGPT]), aspartate aminotransferase (AST; formerly serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase [SGOT]), alkaline phosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase, γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels

iv. Serum bilirubin level: Total, indirect, direct

vi. Serum amylase, lipase, cholinesterase levels

vii. Prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR)

viii. Level of α-fetoprotein, a tumor marker used to diagnose liver cancer; level of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9), a tumor marker used for the diagnosis of pancreatic or hepatobiliary cancer

ix. Carcinoembryonic antigen level

x. Levels of smooth muscle antibody (SMA), antimitochondrial antibody (AMA), antinuclear antibody (ANA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), and anti–liver-kidney microsomal antibody (anti-LKM antibody), an assay used to diagnose autoimmune disorders

xii. Hepatitis serologic testing (hepatitis A, B, C)

xiii. Blood cultures (if an infectious process is suspected or with new onset of ascites or abdominal pain)

xiv. Urine: Amylase, lipase, and bilirubin levels; culture and sensitivity testing; urinalysis; microalbumin level

(a) Total iron-binding capacity, serum iron level, ferritin level

(b) Serum transferrin, prealbumin, retinol-binding protein levels

xvi. Stool: Occult blood, fat, protein, ova and parasites, cultures

i. Abdominal flat-plate radiography: To visualize the position, size, and structure of the abdominal contents, truncal skeleton, and soft tissues of the abdominal wall. Dilated bowel loops, free air, fluid accumulations, and intramural bowel gas can be identified on plain radiographic films.

ii. Upper GI series: Contrast is used to visualize the position, contours, and size of the entire upper GI tract (especially the stomach and duodenum); to detect ulcers, tumors, strictures, and obstructions. Barium swallow is used to examine swallowing, motility, and emptying in the esophagus.

iii. Small bowel follow-through: To visualize the small bowel from the ligament of Treitz to the ileocecal valve to detect ulcers, tumors, diverticula, polyps, and inflammatory bowel disease

iv. Lower GI series: Barium enema is used to visualize the position, contours, and size of the entire lower GI tract; to detect ulcers, tumors, strictures, obstructions, polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, and diverticula; and to evaluate melena after inconclusive upper GI series

v. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) or upper endoscopy: Visualization and photography of the esophagus, stomach, and proximal duodenum by means of an endoscope

(a) To detect obstruction, strictures, ulcers, or tumors

(b) To evaluate melena, hematemesis, heme-positive nasogastric drainage, dysphagia, odynophagia, dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting, or unexplained abdominal pain

(c) To perform biopsy and obtain brush cytology and culture specimens; to place stents; to remove foreign bodies; to place feeding tubes; or to control bleeding

vi. Flexible sigmoidoscopy: Visualization and photography of the rectum, sigmoid colon, and descending colon up to 65 cm by means of a flexible sigmoidoscope or colonoscope

(a) To detect inflammatory disease, tumors, obstruction, strictures, and polyps

(b) To evaluate unexplained chronic diarrhea or pain, lower GI bleeding

(c) To perform biopsy, obtain specimens for brush cytology studies, perform polypectomy, and obtain culture specimens; to remove foreign bodies; and to control bleeding

vii. Colonoscopy: Visualization and photography of the colon from the rectum to the ileocecal valve by means of a colonoscope

(a) To detect polyps, strictures, obstruction, tumors, or inflammatory disease

(b) To evaluate lower GI bleeding, unexplained chronic abdominal pain, unexplained iron-deficiency anemia, or changes in bowel patterns

(c) To perform biopsy, obtain specimens for brush cytology studies, perform polypectomy, and obtain culture specimens; to remove foreign bodies; and to control bleeding

viii. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): Visualization and photography of the biliary and/or pancreatic ducts by means of a flexible (fiberoptic) endoscope

(a) To detect tumors, bile duct stones, obstruction, and pancreatitis

(b) To evaluate jaundice, elevated levels on liver tests, and chronic unexplained abdominal pain

(c) To perform biopsy and obtain specimens for brush cytology studies and cultures; to place stents; or to remove stones

ix. Angiography: Selective catheterization of the visceral arterial system and portal venous system, to reveal vessel sizes, patency, and flow rates of the vessels as well as the direction of the blood flow

x. Cholangiography: Radiopaque dye is used to enhance the radiograph and allow visualization of the gallbladder and bile ducts

xi. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen: Can be done with or without intravenous, oral, or rectal contrast

(a) To visualize the gallbladder, liver, pancreas, spleen, loops of the small and large intestine, extrahepatic bile ducts, and portal vein

(b) To determine the presence of vascular problems, infection, tumors, and pancreatic pseudocyst

(c) Use of contrast-enhanced images allows for improved visualization of tumors, vascularity of masses, and differences within bowel loops

xii. Positron emission tomography (PET): Use of radioisotopes (carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and fluorine, and some metals like copper and gallium and their decay products) to reveal physiologic function, not anatomic structure. It is used to evaluate for colorectal, liver, pancreatic, and neuroendocrine diseases.

xiii. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

(a) Same applications as CT with a greater potential for tissue characterization and a greater ability to diagnose and characterize diffuse liver and pancreatic disease

(b) Can also detect arterial and venous blood flow, vessel patency, bile ducts, and the presence of strictures within the ducts

(c) Less effective than CT for evaluating disorders of the bowel because the movement of the intestine degrades MRI images

xiv. Ultrasonography of the abdomen: To visualize the sizes and echotextures of the gallbladder, liver, pancreas, and spleen; to determine the presence or absence of disease (fatty infiltration, cirrhosis), the cause of masses (cysts, abscesses, tumors), and the presence of foreign bodies (gallstones); to evaluate the bile ducts and accumulation of fluids; and to determine the direction of blood flow, the development of collateral vessels, and vessel patency.

i. Biopsy: Needle or forceps aspiration of tissue from the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, colon, rectum, or liver or soft tissues masses for histologic analysis

ii. Abdominal paracentesis: Withdrawal of peritoneal fluid for diagnostic purposes or symptomatic relief by means of a large-bore needle

iii. Peritoneoscopy (laparoscopy): Examination of the structures and organs within the abdominal cavity by means of a laparoscope

iv. Gastric lavage: Insertion of a gastric tube through the nose or mouth to examine the gastric contents or secretions for occult blood or pH

v. Schilling’s test: Vitamin B12 absorption test to determine whether vitamin B12 absorption is defective and if the cause is intrinsic factor deficiency. Oral radioactively labeled vitamin B12 and intrinsic factor, and intramuscular nonradioactive vitamin B12 are administered, and 24- to 48-hour urine excretion is measured.

Patient Care

1. Inability to establish or maintain a patent airway

a. Description of problem: With acute hemorrhage or encephalopathy there may be an inability to maintain the airway due to altered levels of consciousness or possible aspiration due to vomiting. Clinical findings may include altered rate and depth of respirations, decreased oxygen saturation, dyspnea or tachypnea, and cyanosis.

b. Goals of care: Reestablish and maintain a patent airway

c. Collaborating professionals on health care team: Physician, nurse, anesthesiologist, respiratory therapist, radiologist

d. Interventions: See Chapter 2

e. Evaluation of patient care: Patent airway and no signs of aspiration

a. Description of problem: Associated with hemorrhage, GI fluid and blood losses, third-spacing, or sepsis. Clinical findings may include the following:

i. Anxiety or diminished mental status

ii. Tachycardia; decreased pulse pressure, cardiac output, and cardiac index

iii. Orthostatic hypotension progressing to profound hypotension

v. Decreased hemoglobin level, hematocrit, and platelet count; increased INR; hematemesis or melena

b. Goals of care: Restore normal circulating fluid volume

c. Collaborating professionals on health care team: Physician, nurse, laboratory technician, pharmacist, blood bank personnel

d. Interventions: See Chapters 3 and 5

e. Evaluation of patient care: Restoration of adequate circulating volume as evidenced by vital signs, cardiac filling pressures, serum electrolyte and lactate levels, urine output, and oxygen delivery

3. Electrolyte and/or acid-base imbalances

a. Description of problem: May be related to hemorrhage, GI losses, third-spacing, sepsis, or renal failure (see Chapters 2 and 5 for specific clinical findings)

b. Goals of care: Restore and maintain electrolyte balance and normalize pH

c. Collaborating professionals on health care team: Physician, nurse, pharmacist, laboratory technician, respiratory therapist

d. Interventions: See Chapters 2 and 5

e. Evaluation of patient care: Maintenance of normal values for serum electrolytes, lactate, and arterial blood gases

a. Description of problem: May be associated with inadequate intake, anorexia (intake less than body requirements) due to nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, reduced absorption, or increased metabolic needs

b. Goals of care: Ensure that minimum daily requirements for both calories and nutrients are met

c. Collaborating professionals on health care team: Physician, dietitian, total parenteral nutrition team, pharmacist

i. Perform accurate monitoring and recording of patient weight; monitoring of intake and output, including calorie count

ii. Assess bowel sounds and for signs of malabsorption or obstruction

iii. Complete a comprehensive nutritional assessment, including increases in energy requirements

iv. Administer oral and/or parenteral nutritional support and monitor the patency of feeding tubes if used

v. Monitor for complications of central venous catheters if used

vi. Monitor patient response to and tolerance of the nutritional regimen (e.g., electrolyte balance, hydration, hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia)

SPECIFIC PATIENT HEALTH PROBLEMS

1. Pathophysiology: Condition of complex etiology characterized by the sudden onset of abdominal pain, associated with inflammation of the peritoneal cavity and usually necessitating emergency surgical intervention

a. Perforated or ruptured viscus (esophagus, stomach, liver, pancreas, gallbladder, bile duct, bowel, appendix, or diverticulum) caused by erosion, technical error during surgery or other procedure, foreign body, trauma, or infection

b. Perforated or ruptured blood vessel as in peptic ulcer disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, tumor, or trauma

c. Bowel ischemia: Decrease in blood flow or tissue perfusion that can be acute or chronic, occlusive or nonocclusive

i. Arterial occlusion (embolus or thrombus)

ii. Venous occlusion (hypercoagulable state, trauma)

iii. Nonocclusive (cardiopulmonary bypass, vasoconstrictive medication, dehydration, shock, or congestive heart failure)

d. Bowel obstruction: Blockage of the forward flow of intestinal contents

i. Classification: Acute, subacute, chronic, or intermittent (only acute obstruction leads to infarction or strangulation)

(a) Intrinsic: Originates within the lumen of the intestine

(b) Extrinsic: Originates outside the lumen of the intestine

(a) Simple: Does not occlude blood supply

(b) Strangulated: Occludes blood supply

(c) Closed loop: Obstruction at each end of an intestinal segment

(a) Mechanical (gallstones, tumor, impactions, foreign bodies, inflammatory bowel diseases, adhesions, volvulus, intussusception)

(b) Functional (paralytic ileus after abdominal surgery or caused by electrolyte imbalances, peritonitis, spinal fractures, megacolon, ischemia, pancreatitis)

a. Persistent severe abdominal pain, referred pain

b. Nausea, vomiting, reflux, or anorexia

c. Alteration in bowel patterns

d. Abdominal distention; hyperactive or hypoactive bowel sounds

e. Guarding of the abdomen, rebound tenderness

4. Diagnostic study findings: Differential diagnosis is complex

i. Elevated white blood cell (WBC) count with a shift to the left: Elevated segmented neutrophil and basophil counts, increased numbers of bands (immature neutrophils)

ii. Elevated alkaline phosphatase level

iii. Findings consistent with a diagnosis of pancreatitis; elevated serum amylase, lipase levels

iv. Findings consistent with hemorrhage

v. Arterial blood gas levels: Metabolic acidosis

vi. Blood and body fluid culture results positive for infectious organisms

i. Abdominal flat-plate radiography: Alteration in the position, size, or structure of abdominal contents; free air or free fluid in the abdomen

ii. Abdominal ultrasonography: Masses (cysts, abscesses, tumors), foreign bodies (gallstones), infarction

iii. Cholangiography: Cholangitis

iv. ERCP: Biliary or pancreatic stones, obstruction of ducts

v. Arteriography: Bleeding, infarction

vi. Abdominal CT or MRI: Vascular problems, infection, masses, or pancreatic pseudocyst

c. EGD: Bleeding from peptic ulcer, esophageal tear

d. Flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy: Lower GI ulceration, perforation, bleeding, abscess, ischemia

e. Abdominal paracentesis: Blood, bile, pus, urine, or feces in abdominal cavity

f. Peritoneoscopy (laparoscopy): Bleeding, perforation, rupture, abscess, ischemia

a. Restore hemodynamic equilibrium and fluid balance

b. Restore electrolyte balances

c. Restore optimal GI function

6. Collaborating professionals on health care team: Physician, nurse, dietitian, respiratory therapist, pharmacist, radiologist or technician, consultant (e.g., hepatologist, infectious disease specialist)

a. Anticipated patient trajectory: Patients with an acute abdomen can differ greatly in their clinical course and status at discharge, depending on factors such as age and preexisting conditions. Throughout their course of recovery and discharge, patients with an acute abdomen may be expected to have needs in the following areas:

i. Positioning: As the patient’s condition and comfort dictate

ii. Skin care: Postoperative wound care and pressure relief are required, because the patient is susceptible to skin breakdown from diarrhea, fistula formation, wound drainage, dehydration, hypotension, and malnutrition

iii. Pain management: Hypotension makes pain management more complex; however, dosage reduction and nonpharmacologic techniques may be effective. Frequent reassessment and gradual titration of medication required. (See discussion of pain in Chapters 4 and 10.)

iv. Nutrition: Nutritional needs will be increased because of increased metabolic needs. There will have been a reduction in intake prior to surgery because of the acute condition. Postoperatively the reduction in intake will continue in the face of increased metabolic demands of surgery, fever, wound healing, and complications such as infection. Cause of the condition and the caloric requirements will determine how these metabolic needs are met (enteral or parenteral route).

v. Infection control: Patients with blunt or penetrating trauma, infection, or pancreatitis will have an increased risk of infectious complications secondary to the ruptured viscus or translocation of bacteria. Vigilance is required to identify signs and symptoms of an infectious process early and initiate treatment promptly.

vi. Transport: Patient will undergo a variety of diagnostic tests and procedures, which will require that the patient be maintained in a mobile environment. Monitoring of various tubes, drains, and catheters is required in addition to monitoring of vitals signs.

vii. Discharge planning: Patient may need assistance at home for dressings, intravenous antibiotics, wound care, parenteral or enteral nutrition. Physical therapy may also be required.

viii. Pharmacology: Patients will be receiving a complex variety of medications postoperatively (antibiotics, insulin, narcotics, anxiolytics, vasopressors, inotropic agents, proton pump inhibitors, diuretics, cathartics)

ix. Psychosocial issues: Due to the acute nature of the illness, the family may be unprepared for role changes and financial issues. There may be significant alteration in body image and/or resumption of prior roles in the family.

x. Treatments: Postoperatively the patient can receive noninvasive treatments (motility agents) as well as invasive treatments (additional surgery)

xi. Ethical issues: Living will, durable power of attorney for health care, refusal of treatment, consent for treatment

(a) Mechanism: Translocation of bacteria through the lumen of an ischemic GI tract, abscess, invasive monitoring lines

Acute (Fulminant) Liver Failure

a. Clinical syndrome defined as the development of hepatic encephalopathy within 8 weeks of symptoms or within 2 weeks of the onset of jaundice

b. Occurs in individuals with a history of normal liver function and is characterized by massive hepatocellular necrosis as evidenced by a raised serum alanine transaminase level; prolonged coagulation and hypoglycemia can also occur

c. Except in cases of acute fulminant liver failure caused by acetaminophen toxicity, the mortality rate is 80% to 100% without liver transplantation

a. Viral hepatitis: Acute hepatitis A and B

c. Acetaminophen toxicity: Liver failure from intentional overdose and unintentional therapeutic misadventure has a better prognosis than that resulting from other causes

d. Hepatotoxic drugs or substances

e. Mushroom poisoning (e.g., due to Amanita phalloides, Amanita verna, and Amanita venosa; Galerina autumnalis, Galerina marginata, and Galerina venenata; Gyromitra species)

f. Viral infections: Herpesvirus family, especially in immunocompromised patients

g. Acute Wilson’s disease, acute Budd-Chiari syndrome

h. Veno-occlusive disease and graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation

a. Prodromal symptoms (vague, flulike symptoms), fever

c. Hyperventilation, respiratory alkalosis

d. Hepatic encephalopathy (confusion): Rapid progression to hepatic coma

e. Profound coagulopathy and hypoglycemia

k. Eventual cardiovascular collapse

l. Liver is enlarged during the acute inflammatory stage, then becomes atrophied as hepatocellular necrosis progresses

i. Increased levels of AST, ALT, and, to a lesser degree, alkaline phosphatase and GGT. Severe elevations followed by a progression back to normal that may be misinterpreted as improvement in the patient’s status but is not a favorable sign if it occurs in the setting of increasing PT, INR, and bilirubin levels; indicates near-complete hepatocellular necrosis.

ii. Increased serum bilirubin, creatinine, BUN levels

iv. Levels of factors V and VII less than 20% of normal (poor prognostic sign)

v. Decreased serum glucose level, hemoglobin level, and hematocrit

vi. Increased serum lactate level, serum ammonia level, and WBC count

vii. Positive results on cultures of body fluids

viii. Positive results on hepatitis serologic testing or tests for autoimmune markers depending on cause

6. Collaborating professionals on health care team: Physician, nurse, pharmacist, laboratory technician, respiratory therapist, consultant

a. Anticipated patient trajectory: Very unstable with long recovery. Liver transplantation may be necessary when progression of liver failure continues; this requires either a graft from a living donor or a cadaveric liver. Patients may be expected to have needs in the following areas:

i. Positioning: Head of bed raised 30 degrees for treatment of increased ICP

ii. Skin care: Itching can be severe with the onset of jaundice; scratching is unconscious, which results in excoriations; in patients with prolonged coagulation times, this can result in hematoma formation

iii. Pain management: Difficult due to liver failure. Pain is rare because encephalopathy inhibits the reception of transmitted pain impulses. Consultation with a hepatologist necessary if pain medication required.

iv. Nutrition: Metabolic rate can be increased; fluid balance is a problem with renal failure. Special enteral and parenteral solutions required due to liver and renal dysfunction.

v. Infection control: Immobility, altered level of consciousness, invasive lines, and depressed immune system results in increased risk of infection

vi. Transport: Monitor for changes in ICP; mobile environment increases the risk of infection

vii. Discharge planning: Recovery is long, and the patient and family will need assistance with home care, rehabilitation, medications, office visits

viii. Pharmacology: Patient will be taking a complex regimen of medications, and alternative choices (shorter-acting drugs or drugs with shorter half-lives) and dosing patterns (every 12 hours instead of every 6 or 8 hours) will be required due to liver dysfunction

ix. Psychosocial issues: Acuity of the situation will have a profound impact on the family and increase stress

(b) Invasive: Surgery, endoscopy with esophageal variceal ligation or sclerosis, colonoscopy with cauterization, angiography with embolization

xi. Ethical issues: Cause of the liver disease can affect the potential for liver transplantation and may lead to a discussion regarding end-of-life issues

(a) Mechanism: Depressed immune system and breaks in the skin barrier due to monitoring needs; altered level of consciousness and risk of aspiration

ii. Brainstem herniation (most common cause of death in fulminant liver failure) or intracranial hemorrhage

(a) Mechanism: Increased coagulation times increase the risk of intracranial bleeding and pulmonary hemorrhage; increased risk of hypoxia, which increases the risk of cerebral edema

(a) Treatment option for fulminant liver failure and end-stage liver disease, and certain cases of hepatoma

(b) Liver disease may reoccur in the transplanted liver

(c) Currently approximately 20,000 patients need liver transplantation; however, only about 6000 are done per year

(1) Cadaveric (deceased) donor

b) Either entire liver or split liver can be used

c) Donor and recipient are matched by blood group, age, size

a) Donor provides 60% of his or her liver

b) Donor between the ages of 21 and 45 years in most cases

c) Recipient usually in healthier condition than those receiving cadaveric organs due to the ability to transplant earlier in the disease course

d) During the early postoperative period the patient requires monitoring for primary nonfunction of the new liver, monitoring for improvement in mentation and levels of coagulation factors, and monitoring for infection

8. Evaluation of patient care: Normalization of liver functions, neurologic function, renal function, and vital signs

Chronic Liver Failure: Decompensated Cirrhosis

a. Cirrhosis is a chronic and usually slowly progressive disease of the liver involving the diffuse formation of connective tissue (fibrosis), nodular regeneration of the liver after necrosis, and chronic inflammation

b. Changes are often irreversible

c. Once the diagnosis of cirrhosis has been made, there is generally a 5- to 10-year period prior to decompensation

a. Alcoholism (Laënnec’s cirrhosis): Development of cirrhosis preceded by a reversible stage of alcoholic hepatitis

i. Viral hepatitis (chronic active hepatitis B, C, F, or G

ii. Drug or toxin induced (prescription drugs, herbs, heavy metals)

c. Autoimmune diseases of biliary stasis (primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis)

d. Inborn errors of liver metabolism: Wilson’s disease (copper metabolism), hemochromatosis (iron metabolism), α1-antitrypsin deficiency

e. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, associated with obesity, hyperlipidemia, protein-calorie malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, chronic corticosteroid use, jejunoileal bypass, short bowel syndrome

a. Fatigue, alteration in sleep pattern: Insomnia, day-night reversal

c. Muscle wasting, weight loss

d. Abdominal distention with ascites

e. Anemia, hematomas, ecchymoses

g. Fetor hepaticus: Musty breath, poor dentition

h. Altered mental status, asterixis

i. Visible stigmata of liver disease: Jaundice, temporal and upper body muscle wasting, parotid enlargement, spider angiomas, palmar erythema, leukonychia, possible clubbing of the fingers, testicular atrophy, gynecomastia in males, striae, the development of abdominal wall collaterals, caput medusae

j. Umbilical hernia, incisional hernia, splenomegaly

k. Hyperdynamic circulation: Increased heart rate, systolic ejection murmur

l. Possible decrease in lung sounds in the bases because of pleural effusions

m. Hepatic bruit (hepatoma or alcoholic hepatitis superimposed on cirrhosis)

a. Laboratory: Depend on the cause and stage of disease

i. ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, GGT levels: Not usually markedly elevated in advanced cirrhosis but depends on the cause of the liver disease

ii. Bilirubin level: Elevated in advanced cirrhosis except in diseases of biliary stasis, in which it is elevated early in the disease

iii. PT, INR: Prolonged PT and increased INR; the most sensitive index of synthetic liver function in a readily available laboratory test

iv. Platelet count: May be decreased due to splenomegaly

v. Blood ammonia level: May be elevated (may be affected by a variety of factors not related to liver disease)

vi. Hemoglobin level, hematocrit: Decreased

vii. BUN, creatinine levels: Decreased until hepatorenal syndrome occurs

viii. Serum sodium level: Decreased (at times critically)

ix. Hepatitis serologic findings: Variable

x. Ascitic fluid: WBC increased absolute neutrophil count, culture results positive for a specific organism

i. CT: Liver volume decreased, spleen volume increased, possible presence of ascites or tumor

ii. MRI, magnetic resonance venography, magnetic resonance arteriography, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography: To evaluate organs, vessels, bile ducts for abnormalities (portal vein thrombosis, liver cancer)

iii. Abdominal ultrasonography: To determine liver and spleen sizes, portal vein patency, presence of hepatoma, bile duct dilatation, presence of small amounts of ascites

c. ERCP: May show dilated bile ducts or beading (narrowing) of ducts

d. Upper GI endoscopy: Reveals esophageal, gastric, and/or duodenal varices

e. Abdominal paracentesis if ascites present: To test fluid for infection (important)

6. Collaborating professionals on health care team: Physician, nurse, dietitian, laboratory technician, physical therapist, consultant (hepatologist, gastroenterologist, surgeon)

a. Anticipated patient trajectory: Patient with chronic liver failure may plateau prior to decompensation then deteriorate rapidly. Patients may be expected to have needs in the following areas:

i. Positioning: Development of orthostatic hypotension dictates the need for slow, deliberate movements to prevent dizziness and falls. Patient with encephalopathy may not be able to coordinate thoughts and movements.

ii. Skin care: Skin will be very dry, and there will be an increase in bruising due to reduction of the platelet count and levels of coagulation factors

iii. Pain management: See Acute (Fulminant) Liver Failure

iv. Nutrition: Ascites may cause early satiety; low zinc levels in liver disease may result in diminished taste or metallic taste; patients develop severe muscle wasting and malnutrition

v. Infection control: Depressed immune system increases the risk of infection; presence of ascites creates the risk of peritonitis

vi. Transport: Mobile environment increases the risk of infection; ascites creates the risk for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

vii. Discharge planning: Recovery periods are short and rehospitalization can be frequent as the patient decompensates. Family and patient will need assistance with home care, rehabilitation, medications, office visits.

viii. Pharmacology: See Acute (Fulminant) Liver Failure

ix. Psychosocial issues: Chronicity of the situation will have a profound impact on the family unit and increase stress. Depression can occur in both the patient and primary caregiver.

x. Treatments: See Acute (Fulminant) Liver Failure

xi. Ethical issues: Lack of available organs and prolonged hospitalizations increase the risk of sepsis, which prevents transplantation and leads to discussions of withdrawal of life support

(1) Increased hydrostatic pressure (higher than 10 mm Hg) within the portal venous system as a result of disruption of the normal liver architecture, which increases the resistance to blood flow into and out of the liver (25% of the cardiac output per minute)

(2) Development of esophageal varices and gastroesophageal variceal bleeding

(3) Splenomegaly: Increased size and congestion of the spleen as a result of portal hypertension, with backward venous congestion via the splenic vein, which results in pancytopenia (anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia)

(1) Restriction on the amount of weight to be lifted (no more than 40 lb)

(2) Frequent monitoring for consequential cytopenia

(3) Use of β-blockers or scheduled endoscopic treatments

(4) Sarfeh shunts may be used for refractory bleeding

(5) Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stents may be used for refractory bleeding

(a) Mechanism: Caused by transudation of fluid from the liver surface as a result of portal and lymphatic hypertension and increased membrane permeability, which lead to increased hydrostatic pressure and decreased oncotic pressure in the portal venous system, characterized by a rise in hepatic sinusoidal pressure, excess hepatic lymph, and hypoalbuminemia

iii. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

(a) Mechanism: Reduced caloric intake, reduced synthesis of albumin by the liver, increased caloric needs

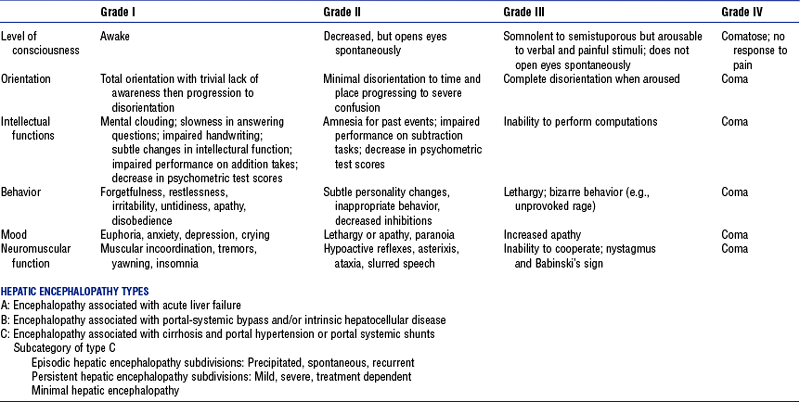

(1) Neuropsychiatric syndrome that develops when nitrogenous and other potentially toxic compounds arising from gut flora accumulate as a result of impaired transformation and elimination

(2) Four grades of alteration of mentation (Table 8-1)

TABLE 8-1

Clinical Assessment of Hepatic Encephalopathy

From Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, et al: Hepatic encephalopathy—definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998, Hepatology 35:716-721, 2002.

(a) Mechanism: Variety of pulmonary conditions develop as a result of hypoxemia, increased intrapulmonary vascular shunting, and changes in intrapleural and intraabdominal pressures; for example, pleural effusions, hepatopulmonary syndrome (pulmonary capillary vasodilation and intrapulmonary shunts)

8. Evaluation of patient care: Optimization of liver function, neurologic function, vital signs, renal function