Chapter 6 The gastrointestinal system

The gastrointestinal history

Presenting symptoms (Table 6.1)

Abdominal pain

| Major symptoms |

Frequency and duration

Try to determine whether the pain is acute or chronic, when it began and how often it occurs.

Aggravating and relieving factors

Pain due to peptic ulceration may or may not be related to meals. Eating may precipitate ischaemic pain in the gut. Antacids or vomiting may relieve peptic ulcer pain or that of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Defaecation or passage of flatus may relieve the pain of colonic disease temporarily. Patients who get some relief by rolling around vigorously are more likely to have a colicky pain, while those who lie perfectly still are more likely to have peritonitis.

Heartburn and acid regurgitation

Heartburn refers to the presence of a burning pain or discomfort in the retrosternal area. Typically, this sensation travels up towards the throat and occurs after meals or is aggravated by bending, stooping or lying supine. Antacids usually relieve the pain, at least transiently. This symptom is due to regurgitation of stomach contents into the oesophagus. Usually these contents are acidic, although occasionally alkaline reflux can induce similar problems. Associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux may be acid regurgitation, in which the patient experiences a sour or bitter-tasting fluid coming up into the mouth. This symptom strongly suggests that reflux is occurring. Some patients complain of a cough that troubles them when they lie down. In patients with gastro

Questions to ask a patient presenting with recurrent vomiting

denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

oesophageal reflux disease, the lower oesophageal sphincter muscle relaxes inappropriately. Reflux symptoms may be aggravated by alcohol, chocolate, caffeine, a fatty meal, theophylline, calcium channel blockers and anticholinergic drugs, as these lower the oesophageal sphincter pressure.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is difficulty in swallowing. Such difficulty may occur with solids or liquids. The causes of dysphagia are listed in Table 6.2. If a patient complains of difficulty swallowing, it is important to differentiate painful swallowing from actual difficulty.1 Painful swallowing is termed odynophagia and occurs with any severe inflammatory process involving the oesophagus. Causes include infectious oesophagitis (e.g. Candida, herpes simplex), peptic ulceration of the

| Mechanical obstruction |

Questions to ask the patient with acid reflux or suspected gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD)

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

oesophagus, caustic damage to the oesophagus or oesophageal perforation.

If the patient complains of food sticking in the oesophagus, it is important to consider a number of anatomical causes of oesophageal blockage.1 Ask the patient to point to the site where the solids stick. If there is a mechanical obstruction at the lower end of the oesophagus, most often the patient will localise the dysphagia to the lower retrosternal area. However, obstruction higher in the oesophagus may be felt anywhere in the retrosternal area. If heartburn is also present, for example, this suggests that gastro-oesophageal reflux with or without stricture formation may be the cause of the dysphagia. The actual course of the dysphagia is also a very important part of the history to obtain. If the patient states that the dysphagia is intermittent or is present only with the first few swallows of food, this suggests either a lower oesophageal ring or oesophageal spasm. However, if the patient complains of progressive difficulty swallowing, this suggests a stricture, carcinoma or achalasia. If the patient states that both solids and liquids stick, then a motor disorder of the oesophagus is more likely, such as achalasia or diffuse oesophageal spasm.

Diarrhoea

Questions to ask a patient who reports difficulty swallowing

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

to an increased interest in defaecation.

Clinically, diarrhoea can be divided into a number of different groups based on the likely disturbance of physiology.2

Questions to ask the patient presenting with diarrhoea

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

disappearance with fasting and by large-volume stools related to the ingestion of food. Osmotic diarrhoea occurs due to excessive solute drag; causes include lactose intolerance (disaccharidase deficiency), magnesium antacids or gastric surgery.

Constipation

It is important to determine what patients mean if they say they are constipated.3 Constipation is a common symptom and can refer to the passage of infrequent stools (fewer than three times per week), hard stools or stools that are difficult to evacuate. This symptom may occur acutely or may be a chronic problem. In many patients, chronic constipation arises because of habitual neglect of the impulse to defecate, leading to the accumulation of large, dry faecal masses. With constant rectal distension from faeces, the patient may grow less aware of rectal fullness, leading to chronic constipation. Constipation may arise from ingestion of drugs (e.g. codeine, antidepressants and aluminium or calcium antacids), and with various metabolic or endocrine diseases (e.g. hypothyroidism, hypercalcaemia, diabetes mellitus, phaeochromocytoma, porphyria, hypokalaemia) and neurological disorders (e.g. aganglionosis, Hirschsprung’sb disease, autonomic neuropathy, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis). Constipation can also arise after partial colonic obstruction from carcinoma; it is, therefore, very important to determine whether there has been a recent change in bowel habit, as this may indicate development of a malignancy. Patients with very severe constipation in the absence of structural disease may be found on a transit study to have slow colonic transit; such slow-transit constipation is most common in young women.

Constipation is common in the later stages of pregnancy.

A chronic but erratic disturbance in defaecation (typically alternating constipation and diarrhoea) associated with abdominal pain, in the absence of any structural or biochemical abnormality, is very common; such patients are classified as having the irritable bowel syndrome.4 Patients who report abdominal pain plus two or more of the following symptoms—abdominal pain relieved by defaecation, looser or more frequent stools with the onset of abdominal pain, passage of mucus per rectum, a feeling of incomplete emptying of the rectum following defaecation and visible abdominal distension—are more likely to have the irritable bowel syndrome than organic disease.

Bleeding

Patients may present with the problem of haematemesis (vomiting blood), melaena (passage of jet-black stools) or haematochezia (passage of bright-red blood per rectum). Sometimes patients may present because routine testing for occult blood in the stools is positive (page 183). It is important to ensure that if vomiting of blood is reported, this is not the result of bleeding from a tooth socket or the nose, or coughing up of blood.

Haematemesis indicates that the site of the bleeding is proximal to or at the duodenum. Ask about symptoms of peptic ulceration; haematemesis is commonly due to bleeding chronic peptic ulceration, particularly from a duodenal ulcer. Acute peptic ulcers often bleed without abdominal pain. A Mallory-Weiss tear usually occurs with repeated vomiting; typically the patient reports first the vomiting of clear gastric contents and then the vomiting of blood. Less-common causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding are presented in Table 6.3.

| Upper gastrointestinal tract |

CRST = calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly and telangiectasia.

* George Kenneth Mallory (b. 1900), professor of pathology, Boston, and Soma Weiss (1898–1942), professor of medicine, Boston City Hospital described this syndrome in 1929.

† Georges Dieulafoy (1839–1911), Paris physician.

‡ Edvard Ehlers (1863–1937), German dermatologist, described the syndrome in 1901, and Henri Alexandre Danlos (1844–1912), French dermatologist, described the syndrome in 1908.

§ Pierre Ménétrier (1859–1935), French physician.

# Johann Friedrich Meckel the younger (1781–1833), Professor of Surgery and Anatomy at Halle. His father and grandfather were also professors of anatomy.

Questions to ask a patient presenting with constipation

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

Questions to ask the patient who presents with vomiting blood (haematemesis)

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem. !

from the upper gastrointestinal tract, although right-sided colonic and small bowel lesions can occasionally be responsible. Massive rectal bleeding can occur from the distal colon or rectum, or from a major bleeding site higher in the gastrointestinal tract. With substantial lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding, it is important to consider the presence of angiodysplasia or diverticular disease (where bleeding more often occurs from the right rather than the left colon, even though diverticula are more common in the left colon). Less-common causes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding are presented in Table 6.3.

Jaundice

Usually the relatives notice a yellow discoloration of the sclerae or skin before the patient does. Jaundice is due to the presence of excess bilirubin being deposited in the sclerae and skin. The causes of jaundice are described on page 185. If there is jaundice, ask about the colour of the urine and stools; pale stools and dark urine occur with obstructive or cholestatic jaundice because urobilinogen is unable to reach the intestine. Also ask about abdominal pain; gallstones, for example, can cause biliary pain and jaundice.5

Pruritus

This symptom means itching of the skin, and may be either generalised or localised. Cholestatic liver disease can cause pruritus which tends to be worse over the extremities. Other causes of pruritus are discussed on page 445.

Abdominal bloating and swelling

A feeling of swelling (bloating) may be a result of excess gas or a hypersensitive intestinal tract (as occurs in the irritable bowel syndrome). Persistent swelling can be due to ascitic fluid accumulation; this is discussed on page 175. It may be associated with ankle oedema.

Lethargy

Tiredness and easy fatiguability are common symptoms for patients with acute or chronic liver disease, but the mechanism is not known. This can also occur because of anaemia due to gastrointestinal or chronic inflammatory disease. Lethargy is also very common in the general population and is not a specific symptom.

Treatment

Questions to ask the patient presenting with jaundice

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem. !

hypersensitivity reaction to chlorpromazine or other phenothiazines, sulfonamides, sulfonylureas, phenylbutazone, rifampicin or nitrofurantoin. Anabolic steroids and the contraceptive pill can cause dose-related cholestasis. Fatty liver can occur with alcohol use, tetracycline, valproic acid or amiodarone. Large blood-filled cavities in the liver called peliosis hepatis can occur with anabolic steroid use or the contraceptive pill. Acute liver cell necrosis can occur if an overdose of paracetamol (acetaminophen) is taken.

Social history

The alcohol history is very important, particularly as alcoholics often deny or understate the amount they consume (see Table 1.3, page 7).6 Contact with anybody who has been jaundiced should always be noted. The sexual history should be obtained. A history of any injections (e.g. intravenous drugs, plasma transfusions, dental treatment or tattooing) in a patient who presents with symptoms of liver disease is important, particularly as hepatitis B or C may be transferred in this way.

Family history

A family history of colon cancer, especially of familial polyps, or inflammatory bowel disease is important. Ask about coeliac disease in the family. A positive family history of jaundice, anaemia, splenectomy or cholecystectomy may occur in patients with haemolytic anaemia (due to haemoglobin abnormalities or auto-immune disease) or congenital or familial hyperbilirubinaemia.

The gastrointestinal examination

Examination of the gastrointestinal system includes a complete examination of the abdomen. It is also important to search for the peripheral signs of gastrointestinal and liver disease. Some signs are more useful than others.7

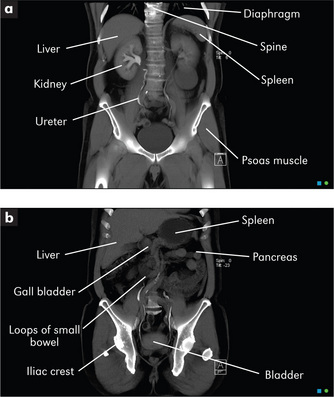

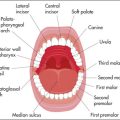

Examination anatomy

An understanding of the structure and function of the gastrointestinal tract and abdominal organs is critical for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal disease (Figure 6.1). The mouth is the gateway to the gastrointestinal tract. It and the anus and rectum are readily accessible to the examiner, and both must be examined carefully in any patient with suspected abdominal disease. The position of the abdominal organs can be quite variable, but there are important surface markings which should be kept in mind during the examination.

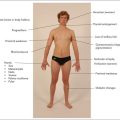

Positioning the patient

For the proper examination of the abdomen it is important that the patient be lying flat with the head resting on a single pillow (Figure 6.2). This relaxes the abdominal muscles and facilitates abdominal palpation. Helping the patient into this position affords the opportunity to make a general inspection.

General appearance

Jaundice

The yellow discoloration of the sclerae (conjunctivae) and the skin that results from hyperbilirubinaemia is best observed in natural daylight (page 185). Whatever the underlying cause, the depth of jaundice can be quite variable.

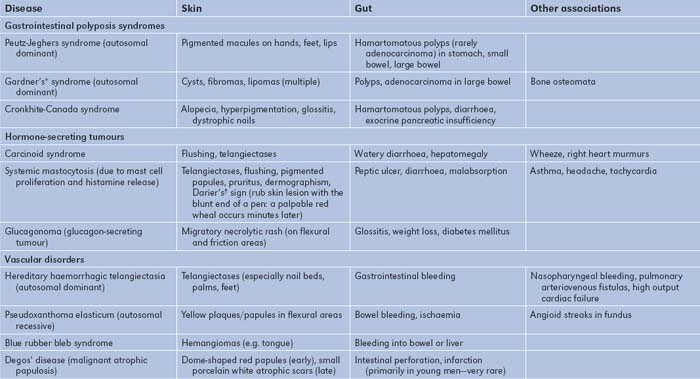

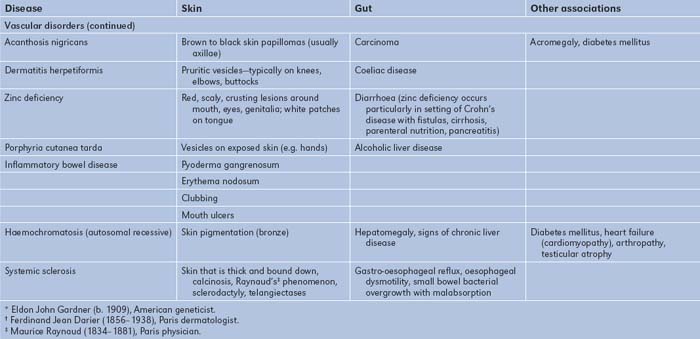

Skin

The gastrointestinal tract and the skin have a common origin from the embryoblast. A number of diseases can present with both skin and gut involvement (Figures 6.3–6.8, Table 6.4).8

Figure 6.3 (above) Glucagonoma: migratory rash involving the groin

From McDonald FS, ed., Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine, with permission. © Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press.

Figure 6.4 (right) Dermatitis herpetiformis

From McDonald FS, ed., Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine, with permission. © Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press.

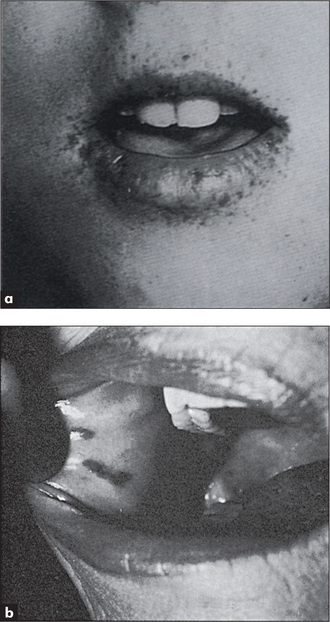

Figure 6.5 Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, with discrete brown-black lesions of the lips

Figure (a) from Jones DV et al, in Feldman M et al, Sleisenger & Fordtran’s gastrointestinal disease, 6th edn, Chapter 112. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1998, with permission. Figure (b) from McDonald FS, ed., Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine, with permission. © Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press.

Figure 6.6 Acanthosis nigricans: (a) axilla; (b) chest wall

From McDonald FS, ed., Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine, with permission. © Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press.

Figure 6.7 (right) Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia involving the lips

From McDonald FS, ed., Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine, with permission. © Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press.

Pigmentation

Generalised skin pigmentation can result from chronic liver disease, especially in haemochromatosis (due to haemosiderin-stimulating melanocytes, to produce melanin). Malabsorption may result in Addisonian-type pigmentation (‘sunkissed’ pigmentation) of the nipples, palmar creases, pressure areas and mouth (page 311).

Peutz-Jeghersc syndrome

Freckle-like spots (discrete, brown-black lesions) around the mouth and on the buccal mucosa (Figure 6.5) and on the fingers and toes, are associated with hamartomas of the small bowel (50%) and colon (30%), which can present with bleeding or intussusception. In this autosomal dominant condition the incidence of gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma is increased.

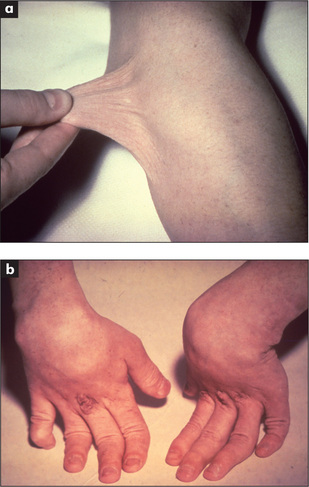

Acanthosis nigricans

These are brown-to-black velvety elevations of the epidermis due to confluent papillomas and are usually found in the axillae and nape of the neck (Figure 6.6). Acanthosis nigricans is associated rarely with gastrointestinal carcinoma (particularly stomach) and lymphoma, as well as with acromegaly, diabetes mellitus and other endocrinopathies.

Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndromed)

Multiple small telangiectasia occur in this disease. They are often present on the lips and tongue (Figure 6.7), but may be found anywhere on the skin. When they are present in the gastrointestinal tract they can cause chronic blood loss or even, occasionally, torrential bleeding. An associated arteriovenous malformation in the liver may be present. This is an autosomal dominant condition and is uncommon.

Mental state

Assess orientation (page 380). The syndrome of hepatic encephalopathy, due to decompensated advanced cirrhosis (chronic liver failure) or fulminant hepatitis (acute liver failure), is an organic neurological disturbance. The features depend on the aetiology and the precipitating factors (page 188). Patients eventually become stuporous and then comatose. The combination of hepatocellular damage and portosystemic shunting due to disturbed hepatic structure (both extrahepatic and intrahepatic) causes this syndrome. It is probably related to the liver’s failure to remove toxic metabolites from the portal blood. These toxic metabolites may include ammonia, mercaptans, short-chain fatty acids and amines.

The hands

Nails

Leuconychia

When chronic liver or other disease results in hypoalbuminaemia, the nail beds opacify (the abnormality is of the nail bed and not of the nail), often leaving only a rim of pink nail bed at the top of the nail (Terry’s nails;eFigure 6.9). The thumb and index nails are most often involved. The exact mechanism is uncertain. It may be that the explanation is compression of capillary flow by extracellular fluid.

The arms

Inspect the upper limbs for bruising. Large bruises (ecchymoses) may be due to clotting abnormalities. Hepatocellular damage can interfere with protein synthesis and therefore the production of all the clotting factors (except factor VIII, which is made elsewhere in the reticuloendothelial system). Obstructive jaundice results in a shortage of bile acids in the intestine, and therefore may reduce absorption of vitamin K (a fat-soluble vitamin), which is essential for the production of clotting factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX and X.

Look for muscle wasting, which is often a late manifestation of malnutrition in alcoholic patients. Alcohol can also cause a proximal myopathy (page 391).

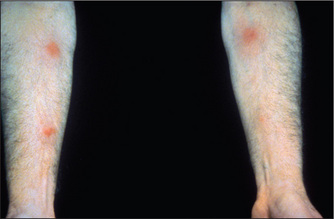

Scratch marks due to severe itch (pruritus) are often prominent in patients with obstructive or cholestatic jaundice. This is commonly the presenting feature of primary biliary cirrhosish before other signs are apparent. The mechanism of pruritus is thought to be retention of an unknown substance normally excreted in the bile, rather than bile salt deposition in the skin as was earlier thought.

Spider naevii (Figure 6.10) consist of a central arteriole from which radiate numerous small vessels which look like spiders’ legs. They range in size from just visible to half a centimetre in diameter. Their usual distribution is in the area drained by the superior vena cava, so they are found on the arms, neck and chest wall. They can occasionally bleed profusely. Pressure applied with a pointed object to the central arteriole causes blanching of the whole lesion. Rapid refilling from the centre to the legs occurs on release of the pressure.

The differential diagnosis of spider naevi includes Campbell de Morganjspots, venous stars and hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Campbell de Morgan spots are flat or slightly elevated red circular lesions that occur on the abdomen or the front of the chest. They do not blanch on pressure and are very common. Venous stars are 2- to 3-cm lesions that can occur on the dorsum of the feet, legs, back and the lower chest. They are due to elevated venous pressure and are found overlying the main tributary to a large vein. They are not obliterated by pressure. The blood flow is from the periphery to the centre of the lesion, which is the opposite of the flow in the spider naevus. Lesions of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (page 228) occasionally resemble spider naevi.

Palpate the axillae for lymphadenopathy (page 229). Look in the axillae for acanthosis nigricans.

The face

Eyes

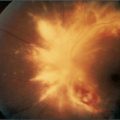

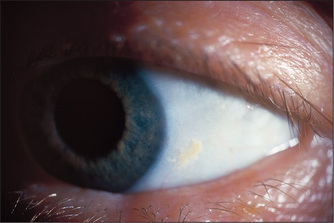

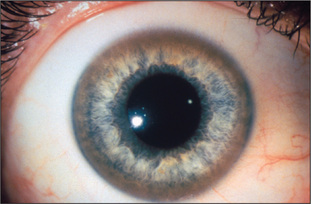

Look first at the sclerae for signs of jaundice (Figure 6.11) or anaemia. Bitot’sk spots are yellow keratinised areas on the sclera (Figure 6.12). They are the result of severe vitamin A deficiency due to malabsorption or malnutrition. Retinal damage and blindness may occur as a later development. Kayser-Fleischer ringsl (Figure 6.13) are brownish green rings occurring at the periphery of the cornea, affecting the upper pole more than the lower. They are due to deposits of excess copper in Descemet’s membranem of the cornea. Slit-lamp examination is often necessary to show them. They are typically found in Wilson’s disease,n a copper storage disease that causes cirrhosis and neurological disturbances. The Kayser-Fleischer rings are usually present by the time neurological signs have appeared. Patients with other cholestatic liver diseases, however, can also have these rings. Iritis may be seen in inflammatory bowel disease (page 191).

Figure 6.12 Bitot spot: focal area of conjunctival xerosis with a foamy appearance

From Mir MA, Atlas of Clinical Diagnosis, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Saunders, 2003, with permission.

Figure 6.13 Kayser-Fleischer rings

From McDonald FS, ed., Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine, with permission. © Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press.

Xanthelasma are yellowish plaques in the subcutaneous tissues in the periorbital region and are due to deposits of lipids (see Figure 4.19, page 57). They may indicate protracted elevation of the serum cholesterol. In patients with cholestasis, an abnormal lipoprotein (lipoprotein X) is found in the plasma and is associated with elevation of the serum cholesterol. Xanthelasma are common in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis.

Periorbital purpura following proctosigmoidoscopy (‘black eye syndrome’) is a characteristic sign of amyloidosis (perhaps related to factor X deficiency) but is exceedingly rare (Figure 6.14).

Salivary glands

Next inspect and palpate the cheeks over the parotid area for parotid enlargement (Table 6.5). Ask the patient to clench the teeth so that the masseter muscle is palpable; the normal parotid gland is impalpable but the enlarged gland is best felt behind the masseter muscle and in front of the ear. Parotidomegaly that is bilateral is associated with alcoholism rather than liver disease per se. It is due to fatty infiltration, perhaps secondary to alcohol toxicity with or without malnutrition. A tender, warm, swollen parotid suggests the diagnosis of parotiditis following an acute illness or surgery. A mixed parotid tumour (a pleomorphic adenoma) is the commonest cause of a lump. Parotid carcinoma may cause a facial nerve palsy (page 343). Feel in the mouth for a parotid calculus, which may be present at the parotid duct orifice (opposite the upper second molar). Mumps also causes acute parotid enlargement which is usually bilateral.

| Bilateral |

* Johann von Mikulicz-Radecki (1850–1905), professor of surgery, Breslau. He described this condition in 1892.

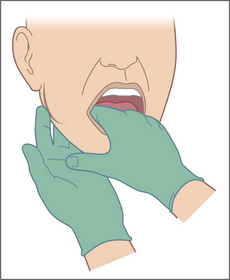

Submandibular gland enlargement is most often due to a calculus. This may be palpable bimanually (Figure 6.15). The examiner’s gloved index finger is placed on the floor of the mouth beside the tongue, feeling between it and fingers placed behind the body of the mandible. It may also be enlarged in chronic liver disease.

The mouth

The teeth and breath

The very beginning of the gastrointestinal tract is, like the very end of the tract, accessible to inspection without elaborate equipment.9 Look first briefly at the state of the teeth and note whether they are real or false. False teeth will have to be removed for a complete examination of the mouth. Note whether there is gum hypertrophy (Table 6.6) or pigmentation (Table 6.7). Loose-fitting false teeth may be responsible for ulcers and decayed teeth may be responsible for fetor (bad breath).

| 1 Phenytoin |

| 2 Pregnancy |

| 3 Scurvy (vitamin C deficiency: the gums become spongy, red, bleed easily and are swollen and irregular) |

| 4 Gingivitis, e.g. from smoking, calculus, plaque, Vincent’s* angina (fusobacterial membranous tonsillitis) |

| 5 Leukaemia (usually monocytic) |

* Jean Hyacinthe Vincent (1862–1950), professor of forensic medicine and French Army bacteriologist, described this in 1898.

TABLE 6.7 Causes of pigmented lesions in the mouth

| 1 Heavy metals: lead or bismuth (blue-black line on the gingival margin), iron (haemochromatosis—blue-grey pigmentation of the hard palate) |

| 2 Drugs: antimalarials, the oral contraceptive pill (brown or black areas of pigmentation anywhere in the mouth) |

| 3 Addison’s disease (blotches of dark brown pigment anywhere in the mouth) |

| 4 Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (lips, buccal mucosa or palate) |

| 5 Malignant melanoma (raised, painless black lesions anywhere in the mouth) |

Other causes of fetor are listed in Table 6.8. These must be distinguished from fetor hepaticus which is a rather sweet smell of the breath. It is an indication of severe hepatocellular disease and may be due to methylmercaptans. These substances are known to be exhaled in the breath and may be derived from methionine when this amino acid is not demethylated by a diseased liver. Severe fetor hepaticus that fills the patient’s room is a bad sign and indicates a precomatose condition in many cases. The presence of fetor hepaticus in a patient with a coma of unknown cause may be a helpful clue to the diagnosis.

TABLE 6.8 Causes of fetor (bad breath)

| 1 Faulty oral hygiene |

| 2 Fetor hepaticus (a sweet smell) |

| 3 Ketosis (diabetic ketoacidosis results in excretion of ketones in exhaled air, causing a sickly sweet smell) |

| 4 Uraemia (fish breath: an ammoniacal odour) |

| 5 Alcohol (distinctive) |

| 6 Paraldehyde |

| 7 Putrid (due to anaerobic chest infections with large amounts of sputum) |

| 8 Cigarettes |

The tongue

Enlargement of the tongue (macroglossia) may occur in congenital conditions such as Down syndrome (page 314) or in endocrine disease, including acromegaly (page 307). Tumour infiltration (e.g. haemangioma or lymphangioma) or infiltration of the tongue with amyloid material in amyloidosis can also be responsible for macroglossia.

Mouth ulcers

This is an important topic because a number of systemic diseases can present with ulcers in the mouth (Table 6.9). Aphthous ulceration is the commonest type seen (Figure 6.16). This begins as a small painful vesicle on the tongue or mucosal surface of the mouth, which may break down to form a painful, shallow ulcer. These ulcers heal without scarring. The cause is completely unknown. They usually do not indicate any serious underlying systemic disease, but may occur in Crohn’so disease or coeliac disease. HIV infection may be associated with a number of mouth lesions (page 457). Angular stomatitis refers to cracks at the corners of the mouth; causes include deficiencies in vitamin B6, vitamin B12, folate and iron.

| Common |

* Halusi Behçet (1889–1948), Turkish dermatologist. He described the disease in 1937.

† Hans Reiter (1881–1969), Berlin bacteriologist, described this in 1916.

Candidiasis (moniliasis)

Fungal infection with Candida albicans (thrush) causes creamy white curd-like patches in the mouth which are removed only with difficulty and leave a bleeding surface. The infection may spread to involve the oesophagus, causing dysphagia or odynophagia. Moniliasis is associated with immunosuppression (steroids, tumour chemotherapy, alcoholism or an underlying immunological abnormality such as HIV infection, or haematological malignancy), where it is due to decreased host resistance. Broad-spectrum antibiotics, which inhibit the normal oral flora, are also a common cause, because fungal overgrowth is permitted. Faulty oral hygiene, iron deficiency and diabetes mellitus can also be responsible. Rarely, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, a distinct syndrome comprising recurrent or persistent oral thrush, fingernail or toenail bed infection and skin involvement, occurs; in some of these patients, endocrine diseases such as hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism or Addison’s disease are associated (page 305).

The neck and chest

Palpate the cervical lymph nodes. It is particularly important to feel for the supraclavicular nodes, especially on the left side. These may be involved with advanced gastric or other gastrointestinal malignancy, or with lung cancer. The presence of a large left supraclavicular node (Virchow’s node) in combination with carcinoma of the stomach is called Troisier’s sign.p Look for spider naevi.

In males, gynaecomastia may be a sign of chronic liver disease. Gynaecomastia may be unilateral or bilateral and the breasts may be tender (Figure 6.17). This may be a sign of cirrhosis, particularly alcoholic cirrhosis, or of chronic autoimmune hepatitis. In chronic liver disease, changes in the oestradiol-to-testosterone ratio may be responsible. In cirrhotic patients, spironolactone, used to treat ascites, is also a common cause. Gynaecomastia may also occur in alcoholics without liver disease because of damage to the Leydig cellsq of the testis from alcohol. A number of drugs may rarely cause gynaecomastia (e.g. digoxin, cimetidine).

The abdomen

Self-restraint is no longer required and it is now time to examine the abdomen itself.

Inspection

The patient should lie flat, with one pillow under the head and the abdomen exposed from the nipples to the pubic symphysis (see Figure 6.2). It may be preferable to expose this area in stages to preserve the patient’s dignity.

Does the patient appear unwell? The patient with an acute abdomen may be lying very still and have shallow breathing (page 186).

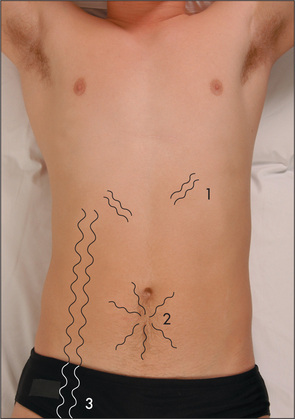

Inspection begins with a careful look for abdominal scars, which may indicate previous surgery or trauma (Figure 6.18). Look in the area around the umbilicus for laparoscopic surgical scars. Older scars are white and recent scars are pink because the tissue remains vascular. Note the presence of stomata (end-colostomy, loop colostomy, ileostomy or ileal conduit) or fistulae. There may be visible abdominal striae following weight loss.

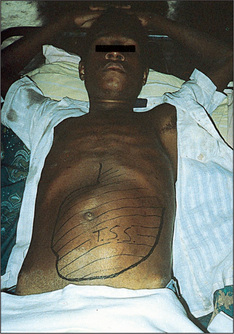

Generalised abdominal distension (Figure 6.19) may be present. All the causes of this sound as if they begin with the letter ‘F’: fat (gross obesity), fluid (ascites), fetus, flatus (gaseous distension due to bowel obstruction), faeces, ‘filthy’ big tumour (e.g. ovarian tumour or hydatid cyst) or ‘phantom’ pregnancy. Look at the shape of the umbilicus, which may give a clue to the underlying cause. An umbilicus buried in fat suggests that the patient eats too much. However, when the peritoneal cavity is filled with large volumes of fluid (ascites) from whatever cause, the abdominal flanks and wall appear tense and the umbilicus is shallow or everted and points downwards. In pregnancy the umbilicus is pushed upwards by the uterus enlarging from the pelvis. This appearance may also result from a huge ovarian cyst.

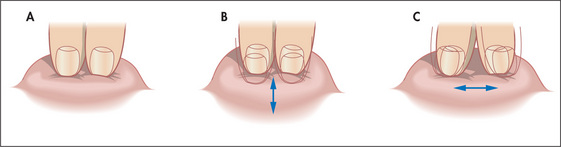

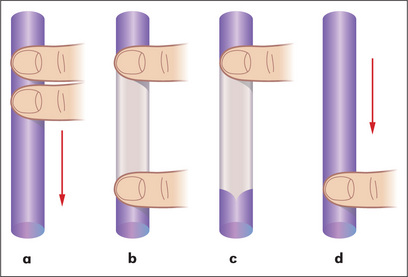

Figure 6.19 Abdomen distended with ascites: umbilicus points downwards, unlike cases of distension due to a pelvic mass

Prominent veins may be obvious on the abdominal wall. If these are present, the direction of venous flow should be elicited at this stage. A finger is used to occlude the vein and blood is then emptied from the vein below the occluding finger with a second finger. The second finger is removed and, if the vein refills, flow is occurring towards the occluding finger (Figure 6.20). Flow should be tested separately in veins above and below the umbilicus. In patients with severe portal hypertension, portal to systemic flow occurs through the umbilical veins, which may become engorged and distended (Figure 6.21). The direction of flow then is away from the umbilicus. Because of their engorged appearance they have been likened to the mythical Medusa’s hair after Minerva had turned it into snakes; this sign is called a caput Medusae (head of Medusa) but is very rare (Figure 6.22). Usually only one or two veins (often epigastric) are visible. Engorgement can also occur because of inferior vena caval obstruction, usually due to a tumour or thrombosis but sometimes because of tense ascites. In this case the abdominal veins enlarge to provide collateral blood flow from the legs, avoiding the blocked inferior vena cava. The direction of flow is then upwards towards the heart. Therefore, to distinguish caput Medusae from inferior vena caval obstruction, determine the direction of flow below the umbilicus; it will be towards the legs in the former and towards the head in the latter. Prominent superficial veins can occasionally be congenital.

Figure 6.20 Detecting the direction of flow of a vein

Adapted from Swash M, ed. Hutchison’s clinical methods, 20th edn. Philadelphia: Baillière Tindall, 1995, with permission.

Figure 6.21 Distended abdominal veins in a patient with portal hypertension

From Mir MA, Atlas of Clinical Diagnosis, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Saunders, 2003, with permission.

Figure 6.22 Prominent veins on the abdominal wall

Based on Swash M, ed. Hutchison’s clinical methods, 20th edn. Philadelphia: Baillière Tindall, 1995.

Skin lesions should also be noted on the abdominal wall. These include the vesicles of herpes zoster, which occur in a radicular pattern (they are localised to only one side of the abdomen in the distribution of a single nerve root). Herpes zoster may be responsible for severe abdominal pain that is of mysterious origin until the rash appears. The Sister Josephr nodule is a metastatic tumour deposit in the umbilicus, the anatomical region where the peritoneum is closest to the skin. Discoloration of the umbilicus where a faintly bluish hue is present is found rarely, in cases of extensive haemoperitoneum and acute pancreatitis (Cullen’s signs—the umbilical ‘black eye’). Skin discoloration may also rarely occur in the flanks in severe cases of acute pancreatitis (Grey-Turner’s signt).

Stretching of the abdominal wall severe enough to cause rupture of the elastic fibres in the skin produces pink linear marks with a wrinkled appearance, which are called striae. When these are wide and purple-coloured, Cushing’s syndrome may be the cause (page 309). Ascites, pregnancy or recent weight gain are much more common causes of striae.

Palpation

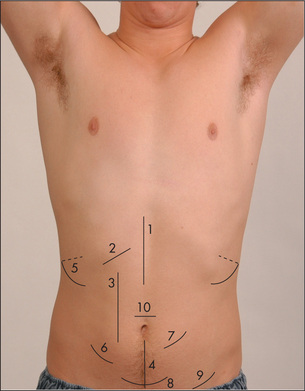

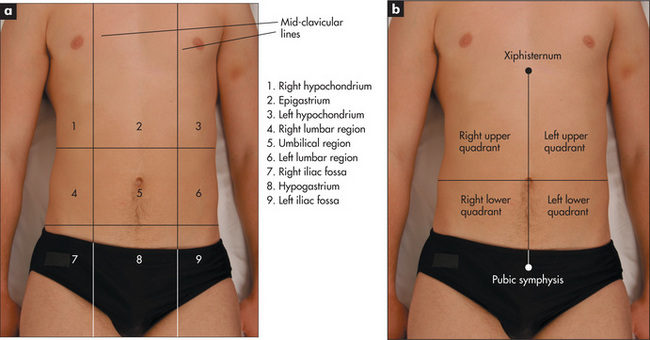

For descriptive purposes the abdomen has been divided into nine areas or regions (Figure 6.23). Palpation in each region is performed with the palmar surface of the fingers acting together. For the palpation of the edges of organs or masses, the lateral surface of the forefinger is the most sensitive part of the hand.

Palpation should begin with light pressure in each region. All the movements of the hand should occur at the metacarpophalangeal joints and the hand should be moulded to the shape of the abdominal wall. Note the presence of any tenderness or lumps in each region. As the hand moves over each region, the mind should be considering the anatomical structures that underlie it. Deep palpation of the abdomen is performed next, though care should be taken to avoid the tender areas until the end of the examination. Deep palpation is used to detect deeper masses and to define those already discovered. Any mass must be carefully characterised and described (Table 6.10).

| For any abdominal mass all the following should be determined: |

| 1 Site: the region involved |

| 2 Tenderness |

| 3 Size (which must be measured) and shape |

| 4 Surface, which may be regular or irregular |

| 5 Edge, which may be regular or irregular |

| 6 Consistency, which may be hard or soft |

| 7 Mobility and movement with inspiration |

| 8 Whether it is pulsatile or not |

| 9 Whether one can get above the mass |

The liver

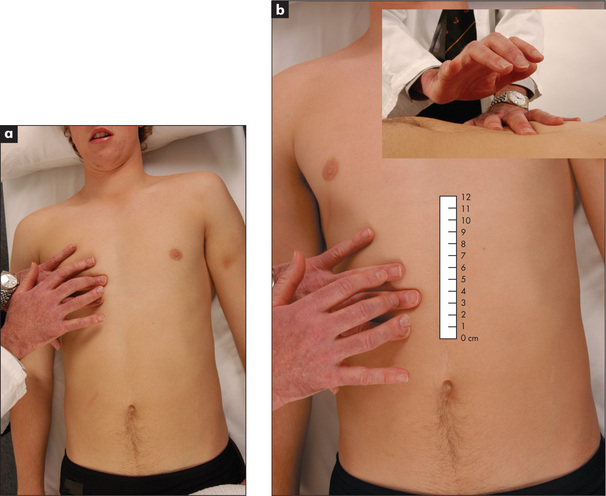

Feel for hepatomegaly (Figure 6.24).10 With the examining hand aligned parallel to the right costal margin, and beginning in the right iliac fossa, ask the patient to breathe in and out slowly through the mouth. With each expiration the hand is advanced by 1 or 2 cm closer to the right costal margin. During inspiration the hand is kept still and the lateral margin of the forefinger waits expectantly for the liver edge to strike it.

If the liver edge is palpable the total liver span can be measured. Remember that the liver span varies with height and is greater in men than women, and that inter-observer error is quite large for this measurement. The normal upper border of the liver is level with the sixth rib in the midclavicular line. At this point the percussion note over the chest changes from resonant to dull (Figure 6.25a). To estimate the liver span (Figure 6.25b), percuss down along the right midclavicular line until the liver dullness is encountered and measure from here to the palpable liver edge. Careful assessment of the position of the midclavicular line will improve the accuracy of this measurement. The normal span is less than 13 cm. Note that the clinical estimate of the liver span usually underestimates its actual size by 2 to 5 cm.

Other causes of a normal but palpable liver include ptosis due to emphysema, asthma or a subdiaphragmatic collection, or a Riedel’s lobe.u The Riedel’s lobe is a tongue-like projection of the liver from the right lobe’s inferior surface; it can be quite large and rarely extends as far as the right iliac fossa. It can be confused with an enlarged gallbladder or right kidney.

Many diseases cause hepatic enlargement and these are listed in Table 6.11. Detecting the liver edge below the costal margin clinically is highly specific (100%) but insensitive (48%)—positive LR 2.5, negative LR 0.5.10,11 Remember, the diseased liver is not always enlarged; a small liver is common in advanced cirrhosis, and the liver shrinks rapidly with acute hepatic necrosis (due to liver cell death and collapse of the reticulin framework).

| Hepatomegaly |

* George Budd (1808–1882), professor of medicine, King’s College Hospital, London, described this in 1845. Hans Chiari (1851–1916), professor of pathology, Prague, described it in 1898.

The gallbladder

The gallbladder is occasionally palpable below the right costal margin where this crosses the lateral border of the rectus muscles. If biliary obstruction or acute cholecystitis is suspected, the examining hand should be oriented perpendicular to the costal margin, feeling from medial to lateral. Unlike the liver edge, the gallbladder, if palpable, will be a bulbous, focal, rounded mass which moves downwards on inspiration. The causes of an enlarged gallbladder are listed in Table 6.12.

| With jaundice

4. Mucocele of the gallbladder due to a stone in Hartmann’s† pouch and a stone in the common bile duct (very rare)

|

| Without jaundice |

* Abraham Vater (1684–1751), Wittenberg anatomist and botanist.

† Henri Hartmann (1860–1952), professor of surgery, Paris.

Murphy’s signv should be sought if cholecystitis is suspected (Good signs guide 6.1). On taking a deep breath, the patient catches his or her breath when an inflamed gallbladder presses on the examiner’s hand, which is lying at the costal margin. Other signs are less helpful.

GOOD SIGNS GUIDE 6.1 Cholecystitis

| Sign | Positive LR | Negative LR |

| Murphy’s sign | 2.0 | NS |

| Back tenderness | 0.4 | 2.0 |

| Right upper quadrant mass | NS | NS |

NS = not significant.

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

The clinician examining for an enlarged gallbladder must always be mindful of Courvoisier’s law,w which states that, if the gallbladder is enlarged and the patient is jaundiced, the cause is unlikely to be gallstones. Rather, carcinoma of the pancreas or lower biliary tree resulting in obstructive jaundice is likely to be present. This is because the gallbladder with stones is usually chronically fibrosed and therefore incapable of enlargement. Note that if the gallbladder is not palpable, and the patient is jaundiced, some cause other than gallstones is still possible, as at least 50% of dilated gallbladders are impalpable (Good signs guide 6.2).

GOOD SIGNS GUIDE 6.2 Gallbladder

| Sign | Positive LR | Negative LR |

| Detecting obstructed bile duct in jaundiced patient | ||

| Palpable gallbladder | 26.0 | 0.7 |

| Malignant obstruction in patient with obstructive jaundice | 2.6 | 0.7 |

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

The spleen

The spleen enlarges inferiorly and medially (Figure 6.26). Its edge should be sought below the umbilicus in the midline initially. A two-handed technique is recommended. The left hand is placed posterolaterally over the left lower ribs and the right hand is placed on the abdomen below the umbilicus, parallel to the left costal margin (Figure 6.27a). Don’t start palpation too near the costal margin or a large spleen will be missed. As the right hand is advanced closer to the left costal margin, the left hand compresses firmly over the rib cage so as to produce a loose fold of skin (Figure 6.27b); this removes tension from the abdominal wall and enables a slightly enlarged soft spleen to be felt as it moves down towards the right iliac fossa at the end of inspiration (Figure 6.27c).

If the spleen is not palpable, the patient must be rolled onto the right side towards the examiner (the right lateral decubitus position) and palpation repeated. Here one begins close to the left costal margin (Figure 6.27d). As a general rule, splenomegaly becomes just detectable if the spleen is one-and-a-half to two times enlarged. Palpation for splenomegaly is only moderately sensitive but highly specific. The positive LR of splenomegaly when the spleen is palpable is 9.6 and the negative LR of splenomegaly if the spleen is not palpable is 0.6.11 The causes of splenomegaly are listed in Table 8.8 (page 230). The causes of hepatosplenomegaly are listed in Table 6.13.

| Chronic liver disease with portal hypertension |

| Haematological disease, e.g. myeloproliferative disease, lymphoma, leukaemia, pernicious anaemia, sickle cell anaemia |

| Infection, e.g. acute viral hepatitis, infectious mononucleosis, cytomegalovirus |

| Infiltration, e.g. amyloid, sarcoid |

| Connective tissue disease, e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Acromegaly |

| Thyrotoxicosis |

The kidneys

The first important differential diagnosis to consider, if a right or left subcostal mass is palpable, must be a kidney. An attempt to palpate the kidney should be a routine part of the examination. The bimanual method is the best. The patient lies flat on his or her back. To palpate the right kidney, the examiner’s left hand slides underneath the back to rest with the heel of the hand under the right loin. The fingers remain free to flex at the metacarpophalangeal joints in the area of the renal angle. The flexing fingers can push the contents of the abdomen anteriorly. The examiner’s right hand is placed over the right upper quadrant.

When palpable, the kidney feels like a swelling with a rounded lower pole and a medial dent (the hilum). However, it is unusual for a normal kidney to be felt as clearly as this. The lower pole of the right kidney may be palpable in thin, normal persons. Both kidneys move downwards with inspiration. The causes of kidney enlargement are listed in Table 7.8 (page 210).

It is particularly common to confuse a large left kidney with splenomegaly. The major distinguishing features are: (i) the spleen has no palpable upper border—the space between the spleen and the costal margin, which is present in renal enlargement, cannot be felt; (ii) the spleen, unlike the kidney, has a notch that may be palpable; (iii) the spleen moves inferomedially on inspiration while the kidney moves inferiorly; (iv) the spleen is not usually ballottable unless gross ascites is present, but the kidney is, again because of its retroperitoneal position; (v) the percussion note is dull over the spleen but is usually resonant over the kidney, as the latter lies posterior to loops of gas filled bowel; (vi) a friction rub may occasionally be heard over the spleen, but never over the kidney because it is too posterior.

Other abdominal masses

The causes of a mass in the abdomen, excluding the liver, spleen and kidneys, are summarised in Table 6.14.

| Right iliac fossa |

Stomach and duodenum

Although many clinicians palpate the epigastrium to elicit tenderness in patients with suspected peptic ulcer, the presence or absence of tenderness is not helpful in making this diagnosis. With gastric outlet obstruction due to a peptic ulcer or gastric carcinoma (page 194), the ‘succussion splash’ (the sign of Hippocrates) may occasionally be present but unfortunately this entertaining sign is more of historical interest than practical use now. In a case of suspected gastric outlet obstruction, after warning the patient what is to come, grasp one iliac crest with each hand, place your stethoscope close to the epigastrium and shake the patient vigorously from side to side. The listening ears eagerly await a splashing noise due to excessive fluid retained in an obstructed stomach. The test is not useful if the patient has just drunk a large amount of milk or other fluid for his or her ulcer; the clinician must then return 4 hours later, having forbidden the patient to drink anything further.

Aorta

Arterial pulsation from the abdominal aorta may be present, usually in the epigastrium, in thin normal people. The problem is to determine whether such a pulsation represents an aortic aneurysm (usually due to atherosclerosis) or not. Measure the width of the pulsation gently with two fingers by aligning these parallel to the aorta and placing them at the outermost palpable margins. With an aortic aneurysm, the pulsation is expansile (i.e. it enlarges appreciably with systole) (Figure 6.28). If an abdominal aortic aneurysm is larger than 5 cm in diameter, it usually merits surgical repair. The sensitivity of examination for finding an aneurysm of 5 cm or larger is 82%.12,13 The sensitivity of the examination for detecting an aneurysm increases pari passu with the size of the aneurysm. The overall LR for a significant aneurysm when one is suspected on palpation is 2.7, with a negative LR of 0.43 if the examination is normal.11

Bladder

An empty bladder is impalpable. If there is urinary retention, the full bladder may be palpable above the pubic symphysis. It forms part of the differential diagnosis of any swelling arising out of the pelvis. It is characteristically impossible to feel the bladder’s lower border. The swelling is typically regular, smooth, firm and oval-shaped. The bladder may sometimes reach as high as the umbilicus. It is unwise to make a definite diagnosis concerning a swelling coming out of the pelvis until you are sure the bladder is empty. This may require the insertion of a urinary catheter.

Testes

Palpation of the testes should be considered if indicated during the abdominal examination (page 215). Testicular atrophy occurs in chronic liver disease (e.g. alcoholic liver disease, haemochromatosis); its mechanism is believed to be similar to that responsible for gynaecomastia.

Anterior abdominal wall

The skin and muscles of the anterior abdominal wall are prone to the same sorts of lumps that occur anywhere on the surface of the body (Table 6.15). So to avoid embarrassment it is important not to confuse these with intra-abdominal lumps. To determine whether a mass is in the abdominal wall, ask the patient to fold the arms across the upper chest and sit halfway up. An intra-abdominal mass disappears or decreases in size, but one within the layers of the abdominal wall will remain unchanged.

| Lipoma |

| Sebaceous cyst |

| Dermal fibroma |

| Malignant deposits—e.g. melanoma, carcinoma |

| Epigastric hernia |

| Umbilical or paraumbilical hernia |

| Incisional hernia |

| Rectus sheath divarication |

| Rectus sheath haematoma |

Pain can arise from the abdominal wall; this can cause confusion with intra-abdominal causes of pain. To test for abdominal wall pain, feel for an area of localised tenderness that reproduces the pain while the patient is supine. If this is found, ask the patient to fold the arms across the upper chest and sit halfway up, then palpate again (Carnett’s test: described by JB Carnett in 1926). If the tenderness disappears, this suggests that the pain is in the abdominal cavity (as tensed abdominal muscles are protecting the viscera), but if the tenderness persists or is greater, this suggests that the pain is arising from the abdominal wall (e.g. muscle strain, nerve entrapment, myositis).14–16 However, the Carnett test may occasionally be positive when there is visceral disease with involvement of the parietal peritoneum producing inflammation of the overlying muscle (e.g. appendicitis).

Percussion

Liver

The liver borders should be percussed routinely to determine the liver span. If the liver edge is not palpable and there is no ascites, the right side of the abdomen should be percussed in the midclavicular line up to the right costal margin until dullness is encountered. This defines the liver’s lower border even when it is not palpable. The upper border of the liver must always be defined by percussing down the midclavicular line. Loss of normal liver dullness may occur in massive hepatic necrosis, or with free gas in the peritoneal cavity (e.g. perforated bowel).

Spleen

Percussion over the left costal margin may be more sensitive than palpation for detection of enlargement of the spleen. Percuss over the lowest intercostal space in the left anterior axillary line in both inspiration and expiration with the patient supine (Figure 6.29). Splenomegaly should be suspected if the percussion note is dull or becomes dull on complete inspiration. Percussion appears to be more sensitive than palpation for the detection of splenomegaly. If the percussion note is dull, palpation should be repeated.

Bladder

An area of suprapubic dullness may indicate the upper border of an enlarged bladder or pelvic mass.

Ascites

The percussion note over most of the abdomen is resonant, due to air in the intestines.17 The resonance is detectable out to the flanks. When peritoneal fluid (ascites) collects, the influence of gravity causes this to accumulate first in the flanks in a supine patient. Thus, a relatively early sign of ascites (when at least 2 litres of fluid have accumulated) is a dull percussion note in the flanks (Good signs guide 6.3). With gross ascites, the abdomen distends, the flanks bulge, umbilical eversion occurs (see Figure 6.19) and dullness is detectable closer to the midline. However, an area of central resonance will always persist. Routine abdominal examination should include percussion starting in the midline with the finger pointing towards the feet; the percussion note is tested out towards the flanks on each side.

| Sign | Positive LR | Negative LR |

| Inspection | ||

| Bulging flanks | 1.9 | 0.4 |

| Oedema | 3.8 | 0.2 |

| Palpation and percussion | ||

| Flank dullness | NS | 0.3 |

| Shifting dullness | 2.3 | 0.4 |

| Fluid wave | 5.0 | 0.5 |

NS = not significant.

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

If (and only if) dullness is detected in the flanks, the sign of shifting dullness should be sought.17 To detect this sign, while standing on the right side of the bed percuss out to the left flank until dullness is reached (Figure 6.30a). This point should be marked and the patient rolled towards the examiner. Ideally 30 seconds to 1 minute should then pass so that fluid can move inside the abdominal cavity and then percussion is repeated over the marked point (Figure 6.30b).

Figure 6.30 Shifting dullness

The presence of bulging in the flanks has good sensitivity and specificity for the detection of ascites. Shifting dullness has both good sensitivity and specificity. The presence of ankle oedema increases the likelihood of ascites. (See Good signs guide 6.3.)

The causes of ascites are listed in Table 6.16.

TABLE 6.16 Classification of ascites by the serum ascites to albumin concentration gradient

| High gradient (>11g/L) |

* Patients with a high serum-to-ascites albumin gradient most often have portal hypertension (97% accuracy).

Auscultation

Friction rubs

These indicate an abnormality of the parietal and visceral peritoneum due to inflammation, but are very rare and non-specific. They may be audible over the liver or spleen. A rough creaking or grating noise is heard as the patient breathes. Hepatic causes include a tumour within the liver (hepatocellular cancer or metastases), a liver abscess, a recent liver biopsy, a liver infarct, or gonococcal or chlamydial perihepatitis due to inflammation of the liver capsule (Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndromex). A splenic rub indicates a splenic infarct.

Venous hums

A venous hum is a continuous, low-pitched, soft murmur that may become louder with inspiration and diminish when more pressure is applied to the stethoscope. Typically it is heard between the xiphisternum and the umbilicus in cases of portal hypertension, but is rare. It may radiate to the chest or over to the liver. Large volumes of blood flowing in the umbilical or para-umbilical veins in the falciform ligament are responsible. These channel blood from the left portal vein to the epigastric or internal mammary veins in the abdominal wall. A venous hum may occasionally be heard over the large vessels such as the inferior mesenteric vein or after portacaval shunting. Sometimes a thrill is detectable over the site of maximum intensity of the hum. The Cruveilhier-Baumgarteny syndrome is the association of a venous hum at the umbilicus and dilated abdominal wall veins. It is almost always due to cirrhosis of the liver. It occurs when patients have a patent umbilical vein, which allows portal-to-systemic shunting at this site. The presence of a venous hum or of prominent central abdominal veins suggests that the site of portal obstruction is intrahepatic rather than in the portal vein itself.

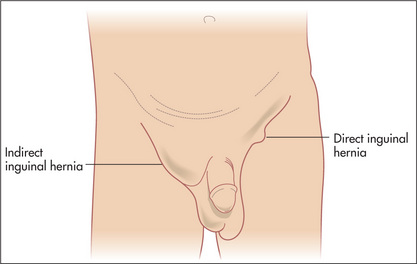

Hernias

The principal sign of a hernia is that of a lump in the groin region. Naturally, not all lumps in the region are hernias (Table 6.17). A lump that is present on standing or during manoeuvres that raise intra-abdominal pressure (such as coughing or straining), and that disappears on recumbency, is easily identified as a hernia. Some hernias, however, are irreducible. Another term used for irreducible is incarcerated, but this term is probably best avoided. Some irreducible hernias contain bowel, which may become obstructed, giving rise to symptoms of small bowel obstruction in addition to the irreducible lump. Sometimes the bowel contents’ blood supply becomes jeopardised, and these are known as strangulated hernias; they are usually painful, red, tense and tender.

| Above the inguinal ligament |

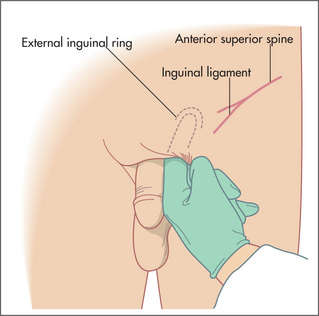

Examination technique

Inspection is carried out initially. Pay careful attention to scars from previous surgery, which may be difficult to see. Look for obvious lumps and swellings. Before palpation is commenced the patient is asked to turn the head away from the examiner and to cough. The examiner’s eyes should be fixed in the region of the pubic tubercle (see below) and note the presence of a visible cough impulse. The patient is then asked to cough again with the examiner inspecting the opposite side.

Inguinal hernias

Inguinal hernias typically bulge above the crease of the groin. They arise from a deficiency above the inguinal ligament and this is where they are usually felt (Figure 6.31). The inguinal ligament lies between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. The pubic tubercle is just above the attachment of the adductor longus tendon to the pubic bone (feel the upper medial aspect of the thigh to palpate the tendon). The internal inguinal ring lies 2 cm above the midpoint of the inguinal ligament.

An indirect inguinal hernia protrudes through the deep inguinal ring. The best surface marking for this point is just above the midpoint of the inguinal ligament, which is halfway between the pubic tubercle and the anterior superior iliac spine (it is the position where the spermatic cord structures enter the inguinal canal). This is lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. A direct hernia, on the other hand, pushes into the inguinal canal posteriorly through a region of weakness known as Hesselbach’s triangle.z This triangle is bounded inferiorly by the inguinal ligament, laterally by the inferior epigastric vessels and medially by the lateral border of the rectus sheath.

The student may be asked to differentiate between direct and indirect inguinal hernias. However, clinically this is difficult and the true nature of an inguinal hernia can often be determined only at the time of operation. The muscular defect in a direct hernia is usually larger than that of an indirect hernia, and as such direct hernias are typically easier to demonstrate and usually reduce immediately and spontaneously. An indirect hernia may often be felt on palpation to slide along the direction of the inguinal canal under the examining fingers.

A large inguinal hernia may descend through the external ring immediately above the pubic tubercle into the scrotum. Gentle invagination of the scrotum with the tip of the gloved little finger in the external ring may be performed to confirm an indirect hernia in men but this can be difficult to interpret without substantial experience (Figure 6.32). A maldescended testis can be confused with an inguinal hernia; always confirm that there is a testis in each scrotum. A large inguinal hernia may present as a lump in the scrotum. It is important initially in this situation to ascertain whether one can get above the lump. If so, the lump is of primary intrascrotal pathology and is not a hernia.

Femoral hernias

Femoral hernias typically bulge into the groin crease at its medial end. Hence they occur lateral to and below the pubic tubercle, just medial to the femoral pulse (about 2 cm away) (Table 6.17). They are less common than inguinal hernias and are not related to the inguinal canal. They are usually smaller and firmer than inguinal hernias and quite commonly do not exhibit a cough impulse. They are frequently irreducible. As such, they are commonly mistaken for an enlarged inguinal lymph node. A cough impulse is rare from a femoral hernia and needs to be distinguished from the thrill produced by a saphena varix when a patient coughs.

Remember that hernias are often bilateral and that two different types may occur on the one side. Sometimes there is also a hydrocele (Figure 7.11, page 217)—one can get above a hydrocele in the inguinal canal but not a hernia.

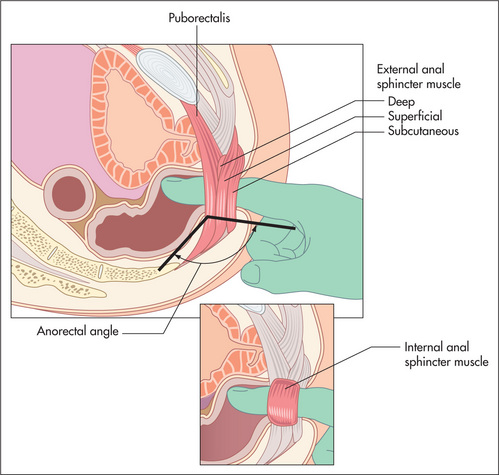

Rectal examination (Figure 6.33)

Figure 6.33 The rectal examination: regional anatomy

From Talley NJ, American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008; 108: 802–803, with permission.

The abdominal examination is not complete without the performance of a rectal examination.18,19 It should be considered in all patients admitted to hospital who are over the age of 40, unless the examiner has no fingers, the patient no anus, or acute illness such as myocardial infarction presents a temporary contraindication.

If there is rectal prolapse, straining may cause a dark red mass to appear at the anal verge; mucosal prolapse causes the appearance of radial folds and concentric folds are a sign of complete prolapse. This mass is continuous with the perianal skin and is usually painless. In cases of mucosal rectal prolapse, the prolapsed mucosa can be felt between the examiner’s thumb and forefinger.

Slowly increasing pressure is applied with the pulp of the finger until the sphincter is felt to relax slightly. At this stage the finger is advanced into the rectum slowly. During entry, sphincter tone should be assessed as normal or reduced. The accuracy of this assessment has been questioned in the past, but more recently has been shown to correlate well with anorectal manometry measurements.20 This resting tone is predominantly (70%–80%) attributable to the internal anal sphincter muscle. Reduced sphincter tone may indicate a sphincter tear. A high anal resting tone may contribute to difficulties with evacuation.

Palpation of the anterior wall of the rectum for the prostate gland in the male and for the cervix in the female is performed first. The normal prostate is a firm, rubbery bilobed mass with a central furrow. It becomes firmer with age. With prostatic enlargement, the sulcus becomes obliterated and the gland is often asymmetrical. A very hard nodule is apparent when a carcinoma of the prostate is present. The prostate is boggy and tender in prostatitis. A mass above the prostate or cervix may indicate a metastatic deposit on Blumer’s shelf.aa

The finger is then rotated clockwise so that the left lateral wall, posterior wall and right lateral wall of the rectum can be palpated in turn. Then the finger is advanced as high as possible into the rectum and slowly withdrawn along the rectal wall. A soft lesion, such as a small rectal carcinoma or polyp, is more likely to be felt this waybb (Table 6.18). Ask the patient to squeeze your finger with the anal muscles as a further test of anal tone.

| Rectal carcinoma |

| Rectal polyp |

| Hypertrophied anal papilla |

| Diverticular phlegmon (recent or old) |

| Sigmoid colon carcinoma (prolapsing into the pouch of Douglas*) |

| Metastatic deposits in the pelvis (Blumer’s shelf) |

| Uterine or ovarian malignancy |

| Prostatic or cervical malignancy (direct extension) |

| Endometriosis |

| Pelvic abscess or sarcoma |

| Amoebic granuloma |

| Foreign body |

Note: Faeces, while palpable, also indent.

* James Douglas (1675–1742), Scottish anatomist and male midwife, physician to Queen Caroline (wife of George II) in London.

The pelvic floor—special tests for pelvic floor dysfunction

The first test is simple: ask the patient to strain and try to push out your finger. Normally, the anal sphincter and puborectalis should relax and the perineum should descend by 1–3.5 cm. If the muscles seem to tighten, particularly when there is no perineal descent, this suggests paradoxical external anal sphincter and puborectalis contraction, which in fact are blocking normal defaecation (pelvic floor dyssynergia). Second, press on the posterior rectal wall and ask if this causes pain; this suggests puborectalis muscle tenderness, which can also occur in pelvic floor dyssynergia. Third, assess whether the anal sphincter and the puborectalis contract when you ask your patient to contract or squeeze the pelvic floor muscles. Puborectalis contraction is perceived as a ‘lift’; that is, the muscle lifts the examining finger toward the umbilicus. Many patients with faecal incontinence cannot augment anal pressure when asked to squeeze. Finally, place your other hand on the anterior abdominal wall while asking the patient to strain again. This provides some information on whether the patient is excessively contracting the abdominal wall (e.g. by performing an inappropriate Valsalva manoeuvre) and perhaps also the pelvic floor muscles while attempting to defaecate, which may impede evacuation. However, the exact value of this test is unclear.

Proctosigmoidoscopy

Procedure

Once the sigmoidoscope has been advanced as far as possible, it should be withdrawn gradually while the circumference of the mucosa is inspected carefully. Look behind for the valves of Houston.cc It is possible to sample faeces from areas away from the anal margin, which can be tested for occult blood and subjected to microbiological examination. Mucosal lesions can also be biopsied.

Common abnormalities seen on sigmoidoscopy

Testing of the stools for blood

False-negative results are not uncommon with colorectal neoplasms because they bleed intermittently. Hence, testing for faecal occult blood from the glove after a rectal examination is of little value,21 and more sensitive and specific testing (e.g. colonoscopy) is required, depending on the clinical setting.

Examination of the gastrointestinal contents

Faeces

Steatorrhoea

Steatorrhoea results from malabsorption of fat. In severe pancreatic disease, oil (triglycerides) may be passed per rectum and this is virtually pathognomonic of pancreatic steatorrhoea (lipase deficiency).

Vomitus

Faeculent vomiting

Brownish-black fluid in large volumes may be vomited in cases of acute dilatation of the stomach. A succussion splash will usually be present. Acute dilatation may occur in association with diabetic ketoacidosis or following abdominal surgery. It represents a medical emergency because of the risk of aspiration; there is a need for urgent placement of a nasogastric tube (see Figure 6.42, page 194).

Urinalysis

Note that testing of the urine can be very helpful in diagnosing liver disease.

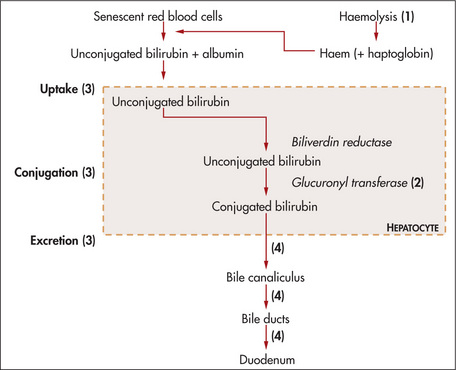

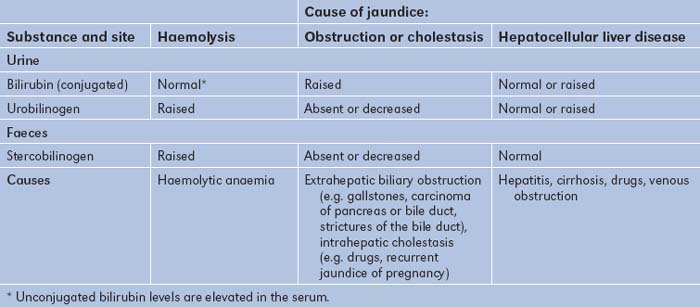

An understanding of the reasons for the presence of bilirubin or urobilinogen in the urine necessitates an explanation of the metabolism of these substances (Figure 6.34).

Total biliary obstruction, from whatever cause, results in absence of urinary urobilinogen, as no conjugated bilirubin reaches the bowel, resulting in pale stools (absence of stercobilin). The conjugated bilirubin, unable to be excreted (the rate-limiting step), leaks from the hepatocytes into the blood and from there is excreted into the urine (normally there is no bilirubin detected in urine). This results in dark urine (excess conjugated bilirubin). Acute liver damage, as in viral hepatitis, may sometimes initially result in excessive urinary urobilinogen, because the liver is unable to re-excrete the urobilinogen reabsorbed from the bowel. These changes are summarised in Table 6.19.

Examination of the acute abdomen

It is very important to try to determine whether a patient who presents with acute abdominal pain requires an urgent operation or whether careful observation with reassessment is the best course of action.22,23 First, take note of the general appearance of the patient. The patient who is obviously distressed with pain or who looks unwell often is, and conversely some reassurance can be gained if a patient does not look sick and appears comfortable.

Assess the patient’s vital signs immediately and recheck these at frequent intervals. Signs of reduced circulating blood volume and dehydration, including tachycardia, postural hypotension, tachypnoea, vasoconstriction and sweating, are of great concern. These signs associated with abdominal pain are usually an indication of substantial intra-abdominal blood loss (such as a ruptured aortic aneurysm), or of substantial fluid losses (e.g. due to acute pancreatitis), or of septic shock (as with a perforated viscus or abscess). Take the patient’s temperature.

Palpate very gently. The presence or absence of peritonism is first assessed. Peritonism is an inflammation that causes pain when peritoneal surfaces are moved relative to each other (Table 6.20; see also Good signs guide 6.4). Traditionally, rebound tenderness is used to assess whether peritonism is present or not. However, if peritonism is present, this test is far more uncomfortable (and cruel) than eliciting tenderness to light percussion. If the patient is extremely apprehensive, ask him or her first to cough; the reaction will be a guide to the degree of peritonism and also its location. Palpation is then continued slowly, but more deeply if possible and if masses are sought. Do not forget to palpate for the pulsatile mass of a ruptured aneurysm. This may be quite indistinct.

| Severe abdominal pain with rigidity of the entire abdominal wall and prostration |

GOOD SIGNS GUIDE 6.4 Peritonitis

| Sign | Positive LR | Negative LR |

| Abdominal examination | ||

| Guarding | 2.6 | 0.6 |

| Rigidity | 5.1 | NS |

| Rebound tenderness | 2.1 | 0.5 |

| Abnormal bowel sounds | NS | 0.8 |

| Rectal examination | ||

| Rectal tenderness | NS | NS |

| Other tests | ||

| Positive abdominal wall tenderness test | 0.1 | NS |

NS = not significant.

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

Auscultation is now performed. In the presence of a bowel obstruction (Good signs guide 6.5), bowel sounds will be louder, more frequent and high-pitched. In an ileus from any cause, bowel sounds are usually reduced or absent.

GOOD SIGNS GUIDE 6.5 Acute bowel obstruction

| Sign | Positive LR | Negative LR |

| Inspection of the abdomen | ||

| Visible peristalsis | 18.8 | NS |

| Abdominal distension | 9.6 | 0.4 |

| Palpation | ||

| Guarding | NS | NS |

| Rigidity | NS | NS |

| Rebound tenderness | NS | NS |

| Auscultation | ||

| Increased (obstructed) bowel sounds | 5.0 | 0.6 |

| Abnormal bowel sounds | 3.2 | 0.4 |

| Rectal examination | ||

| Rectal tenderness | NS | NS |

NS = not significant.

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

Urinalysis may show glycosuria and ketonuria in diabetic ketoacidosis (which can cause acute abdominal pain), haematuria in renal colic, bilirubinuria in cholangitis or proteinuria in pyelonephritis (page 200).

Examine the respiratory system for signs of consolidation, a pleural rub or pleural effusion, and examine the cardiovascular system for atrial fibrillation (a major cause of embolism to a mesenteric artery) or for signs of a myocardial infarction. Examine the back for evidence of spinal disease that may radiate to the abdomen. Remember that herpes zoster may cause abdominal pain before the typical vesicles erupt.

Consider the symptoms and signs of appendicitis.22 Malaise and fever is usually associated with abdominal pain, which is at first worst in the hypogastrium and then moves to the right iliac fossa. The examination will often reveal tenderness and guarding in the right iliac fossa. The pain and tenderness are usually maximum over McBurney’s point.dd He described this point as  to 2 in (3.8 to 5.0 cm) along a line from the anterior superior iliac spine to the umbilicus. Rovsing’s signee is another way of testing rebound tenderness. Press over the patient’s left lower quadrant, then release quickly; this causes pain in the right iliac fossa. The psoas sign is positive when the patient lies on the left side and the clinician attempts to extend the right hip. If this is painful and resisted, the sign is positive. When the appendix causes pelvic inflammation, rectal examination evokes tenderness on the right side. These signs are of variable usefulness (Good signs guide 6.6).

to 2 in (3.8 to 5.0 cm) along a line from the anterior superior iliac spine to the umbilicus. Rovsing’s signee is another way of testing rebound tenderness. Press over the patient’s left lower quadrant, then release quickly; this causes pain in the right iliac fossa. The psoas sign is positive when the patient lies on the left side and the clinician attempts to extend the right hip. If this is painful and resisted, the sign is positive. When the appendix causes pelvic inflammation, rectal examination evokes tenderness on the right side. These signs are of variable usefulness (Good signs guide 6.6).

GOOD SIGNS GUIDE 6.6 Appendicitis

| Sign | Positive LR | Negative LR |

| Vital signs | ||

| Fever | 1.8 | 0.5 |

| Abdominal examination | ||

| Severe right lower quadrant tenderness | NS | 0.2 |

| McBurney’s point tenderness | 3.4 | 0.4 |

| Rovsing’s sign | 2.5 | 0.7 |

| Rectal examination | ||

| Rectal tenderness | NS | NS |

| Others | ||

| Psoas sign | NS | NS |

NS = not significant.

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

Remember that in elderly patients these signs may be reduced or absent.23

Correlation of physical signs and gastrointestinal disease

Liver disease

Signs

The presence of two or more of the following signs suggests cirrhosis: (i) spider naevi; (ii) palmar erythema; (iii) splenomegaly or ascites; (iv) abnormal collateral veins on the abdomen; (v) ascites. See also Good signs guide 6.7.

| Sign | Positive LR | Negative LR |

| General appearance | ||

| Weight loss | NS | NS |

| Skin | ||

| Spider naevi | 4.7 | 0.6 |

| Palmar erythema | 9.8 | 0.5 |

| Distended abdominal veins | 17.5 | 0.6 |

| Abdomen | ||

| Ascites | 4.4 | 0.6 |

| Palpable spleen | 2.9 | 0.7 |

| Palpable gallbladder | 0.04 | 1.4 |

| (Courvoisier’s law) | ||

| Palpable liver | NS | NS |

| Liver tenderness | NS | NS |

NS = not significant.

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

Portal hypertension

Causes

Hepatic encephalopathy

Grading

Causes

Encephalopathy may be precipitated by:

Dysphagia

Dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing) and odynophagia (pain on swallowing) are important symptoms of underlying organic disease. It is important to examine such patients carefully for likely causes (see Table 6.2, page 148).

Signs

Assessment of gastrointestinal bleeding

Determining the possible bleeding site

The causes of acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage are listed in Table 6.3, page 151.

Examine the patient with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding for signs of chronic liver disease and portal hypertension. Part of the assessment should include inspection of the vomitus and stools (pages 183–184) and a rectal examination. Remember that, of patients with chronic liver disease and upper gastrointestinal bleeding, only about half are bleeding from varices. The others are usually bleeding from peptic ulceration (either acute or chronic). Look for evidence of a bleeding diathesis.

Finally, examine the patient for any evidence of skin lesions that can be associated with vascular anomalies in the gastrointestinal tract, although these are rare (Tables 6.3, 6.4). For example, pseudoxanthoma elasticum is an autosomal recessive disorder of elastic fibres that results in xanthoma-like yellowish nodules, particularly in the axillae or neck. These patients may also have angioid streaks of the optic fundus and angiomatous malformations of blood vessels that can bleed into the gastrointestinal tract. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is a group of connective tissue disorders resulting in fragile and hyperextensible skin (Figure 6.35). In a number of types, blood vessels are involved. Type IV is characterised by gastrointestinal tract bleeding, spontaneous bowel perforation, minimal skin hyperelasticity and minimal joint hyperextension.

Malabsorption

Signs

Classification of malabsorption

Inflammatory bowel disease

Ulcerative colitis

Crohn’s disease

Bowel dilatation

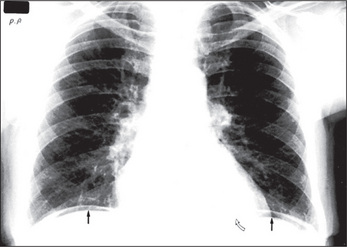

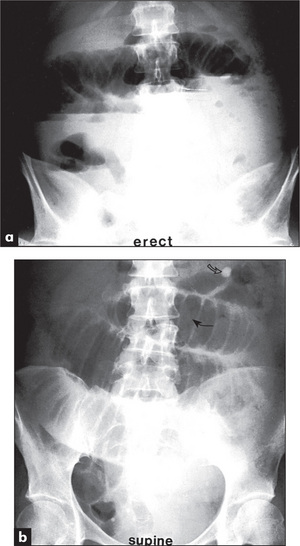

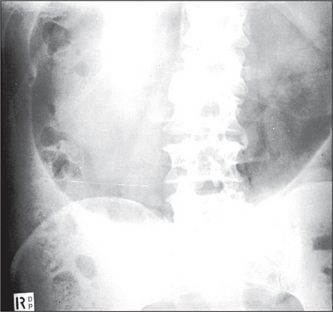

When an ileus (Figure 6.39) or obstruction (Figures 6.40 and 6.41) is present, it is possible to distinguish small- from large-bowel dilatation. The large-bowel loops are peripheral, few in number, have diameters greater than 5 cm, contain faeces, and have haustral margins that do not extend across the bowel lumen. In contrast, the small-bowel loops are central, multiple, between 3 and 5 cm in diameter, and do not contain faeces. Valvulae conniventes which extend completely across the bowel lumen are seen in the jejunal loops.

With gastric dilatation, the stomach may be massively enlarged and distended with air (Figure 6.42).

Calcification

Calcification shows up well against the grey, soft-tissue densities.

About 90% of renal stones are calcified (Figure 7.4, page 203), whereas only 10% of gallstones are calcified. To identify radiolucent gallstones, an ultrasound examination is the test of choice.

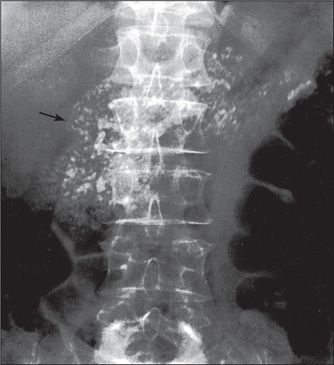

Calcification may be seen in the pancreas in chronic pancreatitis (Figure 6.43).

Summary

The gastrointestinal examination: a suggested method (Figure 6.44)

Figure 6.44 Gastrointestinal system

Then go to the face. Note any scleral abnormality (jaundice, anaemia or iritis). Look at the corneas for Kayser-Fleischer rings. Feel for parotid enlargement; then inspect the mouth with a torch and spatula for angular stomatitis, ulceration, telangiectasiae and atrophic glossitis. Smell the breath for fetor hepaticus. Now look at the chest for spider naevi and in men for gynaecomastia and loss of body hair.

1. Hendrix TR. Art and science of history taking in the patient with difficulty swallowing. Dysphagia. 1993;8:69-73. A very good review of the key historical features that must be obtained when a patient presents with trouble swallowing

2. Talley NJ. Chronic unexplained diarrhea: what to do when the initial workup is negative? Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2008;8(3):178-185.

3. Talley NJ, Lasch KL, Baum CL. A gap in our understanding: chronic constipation and its comorbid conditions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(1):9-19. Jan

4. Ford AC, Talley NJ, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Vakil NB, Simel DL, Moayyedi P. Will the history and physical examination help establish that irritable bowel syndrome is causing this patient’s lower gastrointestinal tract symptoms? JAMA. 2008;300(15):1793-1805.

5. Theodossi A, Knill-Jones RP, Skene A. Interobserver variation of symptoms and signs in jaundice. Liver. 1981;1:21-32. The history and examination permitted a correct clinical diagnosis in jaundiced patients two-thirds of the time