9 The Evidence Base

Definition of Evidence-Based Practice

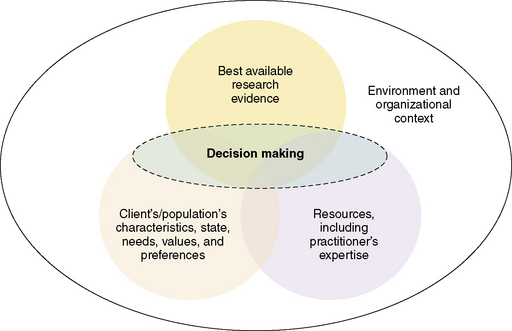

The term evidence-based practice was coined in the 1990s and has been widely embraced by most healthcare disciplines.1 Evidence-based practice (EBP) integrates the best scientific research evidence with clinical expertise of healthcare practitioners and patient and/or family preferences to facilitate clinical decision making.2 Decisions are based upon factors from each domain: the clinical situation, the patient and family preferences, and the research evidence, and individualized to the circumstances. There are multiple models of EBP between and within healthcare disciplines. The conceptual model described by Satterfield et al is a interdisciplinary model based upon the strengths of EBP models and processes from medicine, nursing, psychology, social work, and public health1 (Fig. 9-1). The strength of pediatric palliative care practice stems from the interdisciplinary collaboration of multiple healthcare disciplines. EBP is an approach to problem solving that addresses the needs of the organization, the individual practitioner, the patient, and the family to promote high-quality healthcare. Organizational experiences of quality improvement and financial data, combined with clinical research, clinical experience, and patient and/or family preferences promote shared decision making based upon all contextual factors.3 Palliative care is a relatively young discipline and pediatric palliative care is even younger. The evidence base in palliative care is not robust and there is a paucity of evidence specific to pediatrics.4

Fig. 9-1 The interdisciplinary model of evidence-based clinical decisions.

(Adapted from Satterfield et al. Toward a transdisciplinary model of evidence based practice. Milbank Quarterly, 2009; 87(2), 368–390.)

Evidence-based practice is a process as well as a practice descriptor.5 The process involves defining a practice issue, searching the literature for current research, critically appraising the evidence, synthesizing the evidence to make recommendations for changes in practice, implementing the recommended changes, and evaluating the outcomes. EBP relies on a holistic approach to decision making based less upon expert opinion. Translation of the domains of EBP, scientific research, clinical expertise, and patient and/or family preferences into practice produces products such as changes in clinical practice, clinical guidelines, organizational standards of practice, and opportunities for fostering a research agenda in pediatric palliative care.

The healthcare professions involved in pediatric palliative care, including medicine, nursing, psychology, social work, child life and others, are a science and applied professions with equal contributions to the art and science of clinical practice. The perceived value of evidence may vary depending upon the discipline of practice. Traditional evidence-based medicine relies heavily on randomized clinical trials, yet this approach to generations of evidence is not as practical for pediatric palliative care, where a vulnerable patient population is often excluded from clinical research.6 Most palliative care research is adult-focused and this is one of the challenges to creating pediatric palliative care evidence-based guidelines (Table 9-1). The narrow scope of pediatric palliative care may be too focused for most standard literature search engines. The value of expert clinicians within and between disciplines is unclear and often underestimated in determining EBP recommendations. Evidence must be defined broadly and considered within the context of the specific clinical issue. Evidence is published in a wide variety of journals pertinent to a spectrum of diseases.

TABLE 9-1 Assumptions and Challenges of Evidence-Based Practice in Pediatric Palliative Care

| Assumptions | Challenges |

|---|---|

|

1. The healthcare professions involved in pediatric* palliative care, including medicine, nursing, psychology, social work, child life and others, are a science and an applied profession with equal contribution to the art and science of clinical practice.

2. Evidence is the synthesis of scientific knowledge, clinical expertise and patient and family preferences to guide shared decision making.

|

* (Pediatrics is defined as the care of children, adolescents and young adults.)

Adapted from Satterfield, JM, Spring, B, Brownson, RC, Mullen, EJ, Newhouse, RP, Walker, BB, et al. (2009). Toward a transdisciplinary model of evidence-based practice. The Milbank Quarterly, 87 (2), 368-390; and Newhouse, RP, Dearholt, SL, Poe, SS, Pugh, LC, & White, KM (2007). Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model and Guidelines. Indianapolis: Sigma Theta Tau International.

Levels of Evidence Used in Practice Guideline Development and Implications for Pediatrics

The development of clinical practice guidelines for the management of a variety of diseases and conditions brings together experts to review and summarize current evidence, evaluate the quality of the evidence, and make recommendations for practice. The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP) brought together leaders of five national organizations representing hospice and palliative care. This task force followed a rigorous process of evidence review and consensus development to produce the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care in 2003, with an update in 2009.7 The National Quality Forum, a private, nonprofit membership organization recognized for its national leadership in healthcare quality improvement, reviewed and adopted the NCP guidelines as the basis for its Framework for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality Measurement and Reporting. Clinicians and clinical organizations identified 38 best practices for implementation.8 Quality indicators are being developed to evaluate the impact of those practices.

All clinical recommendations are not equivalent. Their importance will vary with the likelihood of significant benefit or harm avoidance to the patient. The evidence and experience that provides the foundation for the recommendation will also vary in quality depending on the methods used to produce the results. Frameworks have been developed to rate these factors within a set of clinical guidelines. These frameworks use a letter designation for how strongly the practice recommendation is made or how uniform the consensus is for the recommendation, and a numeral designation for the quality of the evidence supporting that recommendation (Tables 9-2 and 9-3).

TABLE 9-2 Framework for Rating Recommendations for Clinical Practice

| Strength of recommendation | Quality of evidence for the recommendation | Modified coding for pediatrics |

|---|---|---|

* Studies that include children or children and adolescents but not studies limited to post-pubertal adolescents.

Adapted from Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents: Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1 infected adults and adolescents; Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral agents in Pediatric HIV Infection. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/Guidelines/GuidelineDetail.aspx?MenuItem=Guidelines&Search=Off& GuidelineID=7&ClassID=1, and http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/Guidelines/GuidelineDetail.aspx?MenuItem=Guidelines&Search=Off&GuidelineID=8&ClassID=1. Department of Health and Human Services. Published August 16, 2010.

TABLE 9-3 National Comprehensive Cancer Network Categories of Evidence and Consensus

| Category 1: The recommendation is based on high level evidence (e.g., randomized controlled trials) and there is uniform NCCN consensus. |

| Category 2A: The recommendation is based on lower level evidence and there is uniform NCCN consensus. |

| Category 2B: The recommendation is based on lower level evidence and there is non-uniform NCCN consensus (but no major disagreement). |

| Category 3: The recommendation is based on any level evidence but reflects major disagreement. |

| All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise specified. |

National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. NCCN categories of evidence and consensus. Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp.

Other research designs that generate evidence include prospective non-randomized trials and observational cohorts; retrospective record reviews, interviews, or surveys; cross sectional studies; qualitative, ethnographic research; and case series or reports. Observational studies may yield associations but cannot determine cause and effect; hence, they are rated lower than RCTs for quality of evidence to support a particular clinical intervention. Similarly, qualitative studies are considered a source of credible evidence but are considered less informative about cause and effects than RCTs.9 Expert consensus is the least-rigorous level of evidence but recognizes the knowledge accumulated through serial observations by experts in the field. It is therefore possible to have strong recommendations that are supported only by expert opinion.

The Working Group on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children is made up of experts from different disciplines. This group is rating their clinical recommendations in the manner described above. However, they recognized that some of their strongest recommendations were based on the adoption of practices proved efficacious in rigorous, well-powered clinical trials of adult patients with minimal supporting evidence in a pediatric population. Following the framework above would result in a rating the supporting evidence as Level III—Expert Opinion. Yet this did not adequately reflect the high quality and compelling results of the evidence that could and should be applied to children with the same life-threatening condition. Therefore the Working Group has modified its rating system to recognize the application in pediatrics of evidence developed in studies of adult patients. An asterisk is added to the numeral to designate that the primary evidence is taken from adult studies and that there is evidence in smaller and more focused pediatric studies that support its application in children.10

Ideally, strong evidence underpins all treatment decisions, yet many clinical situations still demand that clinicians use their best professional judgment in the absence of conclusive evidence. This is precisely the definition of evidence-based practice: the integration of individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence in the care of individual patients.11

There are several reasons why a conclusive level of evidence is difficult to obtain in pediatric palliative care. First, designing and conducting randomized trials with seriously ill or dying patients of any age requires meticulous attention to the treatment alternatives, the burden of outcome assessment,12 and the need for short-term outcome measures given the likelihood that patients may die early in the study. Second, many important questions in palliative care are not answerable through randomized clinical trial design. Finally, the questions that can be answered through RCT, such as comparing two medications for treatment of a specific symptom, are more difficult to conduct in pediatric populations due to a smaller sample of eligible patients, the wide variation in physical development associated with age, and the diversity of disease conditions.13 Although not ideal, pediatric clinicians must sometimes make treatment decisions based on strong evidence obtained in adult trials and the presumption that there is likelihood of similar benefit in children.14

Searching the Palliative Care Literature

Palliative care is a broad category of clinical practice, crossing disciplines, diseases, and ages from prenatal to geriatrics. Thus, literature specific to pediatric palliative care is difficult to identify. Defining a search filter for evidence is essential. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms may not elucidate the true intent of palliative care due to the diffuse nature of the subject area. Using a medical librarian skilled in database searches will help clinicians narrow the focus and screen articles quickly for inclusion or exclusion in review. Hand searches will often be necessary to augment electronic database searches. Multiple text words and phrases are needed in addition to traditional MeSH terms15 (Table 9-4). In a 2007 study, use of this search strategy provided 64.7 percent sensitivity, 92 percent specificity, and 91.1 percent accuracy.16 Information pertinent to searches specific to pediatric palliative care are lacking. However, using the key terms listed in Table 9-4 does yield inclusion of pediatric literature. It is encouraging that the number of clinical trials found in the literature is increasing, although still limited. In a recent systematic review, only 7.22 percent of palliative care literature was noted to be clinical trials.4 Most palliative care research is qualitative or descriptive in nature, thus placing the level of evidence at Level III.3 Clinicians are then challenged to use this level of evidence in conjunction with clinical expertise and patient and/or family preferences to optimize decision making.17

TABLE 9-4 Key MeSH and Text Terms for Searching the Palliative Care Literature

Adapted from Sladek RM,Tieman J, Currow DC (2007): Improving search filter development: a study of palliative care literature. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 7 (18), 1-7.

Examples of EBP in Pediatric Palliative Care

As stated earlier, the science of pediatric palliative care is emerging and critiquing the pediatric palliative care literature is challenging often due to the lack of randomized, controlled trials. Non-randomized clinical studies, cohort studies and even expert opinion provide a base of evidence upon which to plan care. An exemplar is an outstanding example of skilled practice leading to increased knowledge of a subject area.18 Several exemplars exist in pediatric palliative care that demonstrate the commitment to improve the quality of care through the use of evidence-based practice, although not randomized controlled trials. These include use of symptom control, coping strategies, and outcomes of competence, confidence, and the ability to deal with personal grief when caring for dying children with interdisciplinary palliative care. As is the case with much of the palliative care literature, the following three exemplars are retrospective or cross-sectional cohort studies and qualitative or descriptive case studies that provide valuable evidence to influence practice changes.

Looking beyond where children die: determinants and effects of planning a child’S location of death20—LEVEL II, A

Efforts to Build the Evidence Base in Pediatric Palliative Care

Research specifically designed to answer pediatric palliative care questions may benefit from this multicenter approach. The collaboration of several palliative care programs helps to achieve the necessary sample size and to increase the generalization of the study results. Study design can range from RCT to observational cohort studies to cross-sectional surveys. Although single-site studies may be limited by the available sample of eligible patients, specific types of questions, such as the pharmacokinetics of a new medication, may be answered through intensive evaluation of fewer subjects. Other study designs might generate new hypotheses or questions to be answered in future larger, multicenter studies. The “n-of-1 clinical trial” is recognized as an important method for determining the optimum regimen for an individual patient.22 It too may generate hypotheses for larger studies.

Limitations of Evidence in Pediatric Palliative Care

Each child and family receiving palliative care is unique. The usefulness of evidence must be viewed in light of both the individual and specific contextual factors surrounding the clinical practice decisions. Randomized controlled clinical trials are few in palliative care and even less common for pediatrics. Qualitative evidence is valuable and should be considered as appropriate. Clinicians must be skilled at critical appraisal of the evidence. Many models of EBP exist and should be examined for appropriateness to goals of the clinician, the institution, and the patient and family. EBP should not be used as mandatory practice standards but should be guidelines for clinical decision making in light of these goals. The practice of pediatric palliative care is broad but the evidence is often from a narrow focus of a specific symptom or issue. A holistic perspective is required for optimal decision making in pediatric palliative care and isolated evidence must be evaluated in the context of the broad picture. Decisions must be individualized and reassessed throughout the continuum of care. Efficacy of treatment must be evaluated at regular intervals and the treatment plan adjusted as the patient’s condition changes and/or new evidence emerges.23 Education of clinicians, patient, and families is paramount to success of any EBP initiative.

1 Satterfield J.M., Spring B., Brownson R.C., Mullen E.J., Newhouse R.P., Walker B.B., et al. Toward a transdisciplinary model of evidence-based practice. Milbank Q. 2009;87(2):368-390.

2 DiCenso A., Ciliska D., Guyatt G. Introduction to evidence-based nursing. In: DiCenso A., Guyatt G., Ciliska D., editors. Evidence-Based Nursing: A Guide to Clinical Practice. St Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:3-19.

3 Newhouse R.P., Dearholt S.L., Poe S.S., Pugh L.C., White K.M. Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model and Guidelines. Indianapolis: Sigma Theta Tau International, 2007.

4 Tiemann J., Sladek R., Currow D. Changes in the quantity and level of evidence of palliative and hospice care literature: the last century. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(35):5679-5683.

5 Rutledge D.N., Bookbinder M. Processes and outcomes of evidence-based practice. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2002;18(1):3-10.

6 Lorenz K., Lynn J., Morton S.C., Dy S., Mularski R., Shugarman L., et al. End-of-life Care and Outcomes, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 110. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2004. Prepared by the Southern California Evidence-based Practice Center, under Contract No 290–02–0003

7 National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. ed 2. 2009. Available at www.nationalconsensusproject.org. Accessed May 28, 2010

8 National Quality Forum. A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality. Washington, DC: National Quality, 2006.

9 Powers B.A. Critically appraising qualitative evidence. In: Melnyk B.M., Fineout-Overholt E.,., editors. Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing & Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice. Philadelphia,: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:127-167.

10 Working Group on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection. In press. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/PediatricGuidelines.pdf.. Accessed May 28, 2010

11 Sackett D.L., Rosenberg W.M., Gray J.A., Haynes R.B., Richardson W.S. Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71-72.

12 AAHPM. Statement on Palliative Care Research Ethics. 2007. Available at http://www.aahpm.org/positions/researchethics.html Accessed February 6, 2010

13 American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee of Drugs. guidelines for the ethical conduct of studies to evaluate drugs in pediatric populations. Pediatrics. 1995;95(2):286-294.

14 Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: General considerations for pediatric pharmacokinetic studies for drugs and biological products. 1998. Available at www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm072114.pdf. November 30, Accessed February 10, 2010

15 Sladek R., Tieman J., Fazekas B.S., Abernathy A.P., Currow D.C. Development of a subject search filter to find information relevant to palliative care in the general medical literature. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006;94(4):394-401.

16 Sladek R.M., Tieman J., Currow D.C. Improving search filter development: a study of palliative care literature. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7(18):1-7.

17 Whitney S.N., Holmes-Rovner M., Brody H., Schneider C., McCullough L.B., Volk R.J., et al. Beyond shared decision making: an expanded typology of medical decisions. Med Decis Making. 2008;28:699-705.

18 Giordano B.P. Clinical exemplars demonstrate perioperative nurses’ courage and commitment to quality patient care. AORN. 1996;63(1):15-18.

19 Wolfe J., Hammel J.M., Edwards K.E., Duncan J., Comeau M., Breyer J., Aldridge S.A., Grier H.E., Berde C., Dussel V., Weeks J.C. Easing of suffering in children with cancer: is care changing? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1717-1723.

20 Dussel V., Kreicburgs U., Hilden J.M., Watterson J., Moore C., Turner B.G., Weeks J.C., Wolfe J. Looking beyond where children die: determinents and effects of planning a child’s location of death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(1):33-43.

21 Rushton C.H., Reder E., Hall B., Comello K., Sellers D.E., Hutton N. Interdisciplinary interventions to to improve pediatric palliative care and reduce health care professional suffering. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(4):922-933.

22 Evans C.H., Ildstad S.T., editors. Small clinical trials: issues and challenges. 2001. Available at http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10078&page=155 Accessed Feb. 10, 2010

23 American College of Physicians & American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Principles of Palliative Care Practice ACP PIER & AHFS DI® Essentials™. 2009. http://online.statref.com/titleinfo/fxid-92.html. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009