Chapter 107 The Ethics of Wilderness Medicine

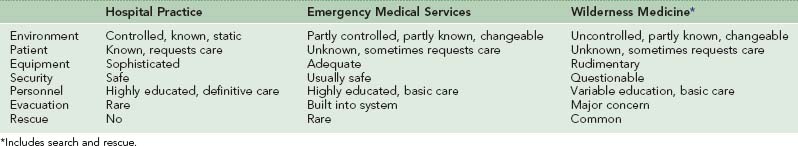

Ethics is the application of moral values and principles to guide human action. Providing care for others often involves intense human interactions and health care providers must frequently examine ethical issues in their work. Although the moral issues in wilderness medicine are an extension of traditional medical ethics, they are not directly comparable with the moral issues that arise either in medicine delivered in health care facilities or the care delivered by urban emergency medical services. Wilderness medicine is unique, and its special attributes create unique ethical problems (Table 107-1). The working environment, concepts that involve standards of care, safety of the rescuers and patients, and even the relationship between the provider and the patient are different in a remote environment than in a traditional medical setting. For example, a hospital’s working environment is rarely a factor considered by the hospital-based practitioner in the determination of what medical care to deliver, but the working environment is of major concern in the wilderness. Similarly, whereas patients usually have a clear legal relationship with the hospital practitioner and arrive requesting care, neither condition is necessarily true in the wilderness setting. Even more striking are the differences between the hospital and the wilderness settings with regard to equipment availability, personnel training, the need for evacuation or rescue, and the provision for the safety of those involved. All of these differences can lead to unique ethical dilemmas in wilderness medicine.

TABLE 107-1 Differences Between Hospital Practice, Emergency Medical Services, and Wilderness Medicine

Application of Values and Principles to Guide Human Activities

Sources of Values

Moral values are the guideposts used to structure an individual’s actions in life. They signify a person’s duties and responsibilities, what is important to them, and how they interact with others. Thomas Aquinas said that there are three vital things for each person: “to know what he ought to believe; to know what he ought to desire; and to know what he ought to do.”1

Professional schooling and interactions further refine how a person’s values are applied. For example, one reason that medical students take anatomy courses is to destroy an ingrained cultural value against mutilating the dead. This allows them to accept and acquire the values of beneficial mutilation (i.e., surgery), handling the dead (i.e., resuscitation, pathology, transplantation), and invading another’s body (i.e., invasive medical procedures).9 In addition, when exposed to clinical practice, medical students, nurses, medics, and other health care providers learn to adopt the values of their preceptors. In any residency program, trainees learn intrinsic professional values, and the majority of trainees behave remarkably like the faculty.

Values in Modern Biomedical Ethics

The concept of comparative or distributive justice suggests that all individuals and groups in society should share equitably in the benefits and burdens of that society. Many society-wide decisions about the allocation of limited health care resources are based on this principle. However, it is a fallacy to extrapolate from this valid principle the idea that individual clinicians can arbitrarily limit or terminate care on a case-by-case basis simply because there exists a need to limit resource expenditures.15

Values Applicable to Wilderness Medicine

Safety or Security

The ethical question here is how much risk and responsibility untrained volunteers have in this type of wilderness crisis. A second issue that has to be considered is the capability of the group to attempt a rescue without endangering themselves and possibly creating the need for a second rescue. As a member of the hiking group, the father in this situation had a responsibility to help; however, because he was technically incapable of the rescue, his only responsible avenue of action was to seek help. Alternatively, bystanders have no fundamental responsibility to help or to assume any risk beyond what they are willing to assume. The man who agreed to be lowered into the crevasse would have been acting ethically if at any point in the rescue attempt he had signaled to the group to pull him up without helping the victims or if he had walked away and not allowed himself to be lowered into the trench in the first place. Despite entreaties from others, bystanders need not justify their participation or nonparticipation to anyone but themselves.20

In contrast, Ernest Shackelton, the appointed leader of a 19th-century attempt to be the first to reach the South Pole, had the responsibility to do his utmost to see his men safely home. During the voyage, their ship broke up in the ice, and the men had to pull lifeboats over ice to reach open sea while struggling against all odds to reach safety. Shackelton’s steady and undaunted leadership is credited with helping all of his men to reach safety.16

A unique ethical problem that arises in wilderness settings—and that has often led to disasters—is when the team (especially the nonmedical team leader) ignores or overrides the medical person’s decision. Individual team members have been harmed and multiple team members lost because factors other than the team members’ safety and well-being were given priority.14,22 Heeding the demands of safety is especially important, because the majority of people who are in the wilderness have risk-taking personalities, leading them to downplay security in favor of adventure.

Utility

The ultimate application of utility in remote settings was described in the great survivor story of the men of the Essex; this is the doomed whaling ship that was the basis for Herman Melville’s Moby Dick.21 As was common after shipwrecks, the men drew lots to decide who would be sacrificed and die so that the others in the small boat could live a little longer without starvation.24 One can argue that, if all of the men consented to this process, then it was ethical, but the very nature of the situation put each man under such extreme duress that it would be questionable if any man’s consent could be considered voluntary. In these types of extreme circumstances, the ethics of draconian decisions such as survivor cannibalism are always fraught with paradoxic ethical dilemmas.9

Decision-Making Capacity and Consent

Many ethical dilemmas in emergency medical care revolve around ascertaining a patient’s decision-making capacity, often linked with consent to—or, more often, refusal of—a medical procedure. Because a basic canon of both ethics and law, as stated by Justice Cardozo, is that “[e]very human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body,”23 these decisions about what action to take can often be made clearer by understanding what is meant by the term decision-making capacity and how it relates to consent. (Note that the word competent is often used when capacity is really what is meant. Competent, meaning, “possessing the requisite natural or legal qualifications,” is a legal term; competency can be determined only by the court.19)

Capacity is always decision-specific rather than global. To have adequate decision-making capacity in any particular circumstance, a person must understand the available options and the consequences of acting on the various options, and he or she must be able to compare any chosen option against the costs and benefits related to a relatively stable framework of personal values and priorities3,4 (Box 107-1). This last requirement is the most difficult to understand and requires a subjective interpretation. The easiest way to assess it is to ask why the individual made such a decision. Disagreement with the physician’s recommendation is not in and of itself grounds for determining whether a person is incapable of making his or her own decisions. In fact, even the refusal of lifesaving medical care may not prove that the person is incapable of making valid decisions if it is made on the basis of firmly held religious beliefs (e.g., a Jehovah’s Witness refusing a blood transfusion).

BOX 107-1

Components of Decision-Making Capacity

From Buchanan AE: The question of competence. In Iserson KV, Sanders AB, Mathieu D, editors: Ethics in emergency medicine, ed 2, Tucson, Ariz, 1995, Galen Press.

A person must be permitted to consent to or to refuse any medical intervention if he or she has decision-making capacity for that decision and if the clinician respects the patient’s autonomy. Three general types of consent exist: presumed, implied, and informed. Presumed consent, sometimes called emergency consent, covers the necessary lifesaving procedures that any reasonable person would wish to have if he or she was lacking decision-making capacity; controlling hemorrhage and securing an airway in an unconscious victim of a fall are common examples. Implied consent is when a person with decision-making capacity cooperates with a procedure, such as holding out an arm to donate blood or to allow initiation of an intravenous line. Informed consent is when a person who retains decision-making capacity is given all of the pertinent facts regarding the risks and benefits of a particular procedure, understands them, and voluntarily agrees to undergo the procedure.11

Bioethical Decision-Making Process*

CHOOSING an Action in the Standard Setting

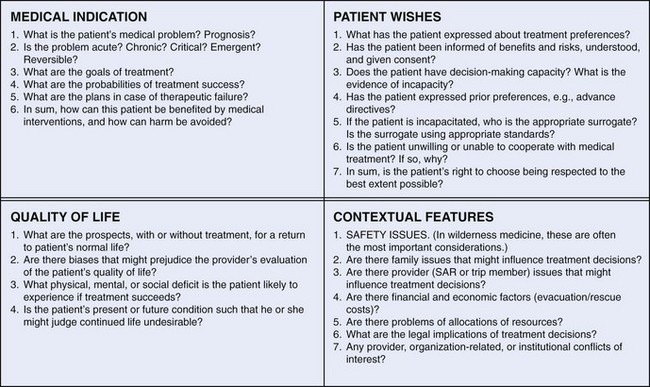

Jonsen and colleagues12 have suggested four groups of factors to consider when determining a course of action in the face of a bioethical dilemma in the standard clinical paradigm. These include the medical indications for the action, the patient’s preferences, consideration of the quality of life, and other contextual factors. These can be seen as an “ethical square,” with the top two boxes (i.e., the first two factors) having more weight (Figure 107-1).

Bioethicists normally feel most comfortable helping to resolve cases using only the medical indications and patients’ wishes, which are all above the double line in Figure 107-1. When these factors are ambiguous, however, two other sets of factors must be considered: contextual factors and quality of life. In the wilderness setting, the primary contextual factor is safety. This may overshadow all other considerations involved in a victim’s treatment. Other contextual factors include financial implications of various treatments and the effect of various options on other trip members. In the standard medical situation, this is, admittedly, a fuzzy area. Related to these—and even more nebulous—are quality-of-life factors. These relate to the nature of a person’s current and presumed future existence as viewed by others. For those who retain decision-making capacity, their autonomous decisions reflect their view of life. In the wilderness setting, time and circumstances usually do not allow clinicians to make quality-of-life judgments.

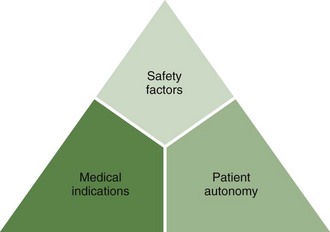

CHOOSING an Action in the Wilderness

The importance of safety factors in the wilderness setting leads to the altered diagram of decision making for ethical problems in wilderness medicine (Figure 107-2). This includes three groups of factors to consider when choosing a course of action: safety, medical indications, and patient autonomy. Within this decision-making model, safety factors must be given the most weight.

Using an Algorithm as a Guide for a Decision

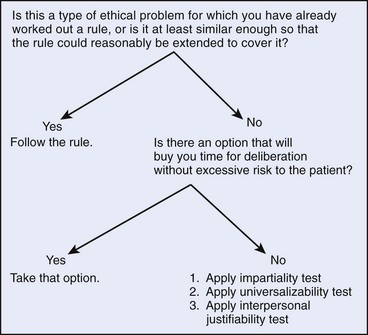

In bioethics, although disagreements may arise regarding the optimal course of action chosen using a specific set of values, general agreement often exists as to what constitutes ethically wrong actions. The method of ethical case analysis described in Figure 107-3 is designed to provide the emergency practitioner with prompt assistance for selecting an ethically correct—although not necessarily a theoretically “best” —course of action.7 This method applies equally well both in the wilderness setting and in the normal hospital setting.

FIGURE 107-3 A rapid approach to emergency ethical problems.

(Modified from Iserson KV: An approach to ethical problems in emergency medicine. In Iserson KV, Sanders AB, Mathieu D, editors: Ethics in emergency medicine, ed 2, Tucson, Ariz, 1995, Galen Press.)

The first step in using the algorithm in Figure 107-3 is to use a known precedent. This is the simplest solution to an ethical dilemma but requires planning in advance, including reading and thinking about ethical problems. Many physicians and other health care professionals are not prepared to do this. Just as with any emergency procedure, wilderness medicine physicians and health care professionals should be prepared with a course of action for the most common ethical dilemmas likely to occur in the wilderness setting.

With no precedent on which to rely and no way to buy time, the health care professional must select a possible course of action and test it for ethical viability. The impartiality test, the universalizability test, and the interpersonal justifiability test are drawn from three different philosophical theories. First, the impartiality test is applied. The practitioner asks whether he or she would ask to have this action performed if he or she was in the patient’s place. In essence, this is a form of the Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have done unto you.” According to John Stuart Mill, this espouses “the complete spirit of the ethics of utility.”18 Second, the universalizability test asks if the health care professional would feel comfortable having all practitioners perform this action in all relevantly similar circumstances. This generalizes the action and asks whether developing a universal rule for the contemplated behavior is reasonable. This is merely a restatement of Kant’s categorical imperative: “Act as if the maxim of thy act were to become by thy will a universal law of nature.”13 Finally, the interpersonal justifiability test asks if the practitioner can supply good reasons to others for his or her action. Will peers, superiors, or the public be satisfied with the action taken and reasons for it? This test uses David Gauthier’s basic theory of consensus values as a final screen for a proposed action.6 If all three tests can be answered in the affirmative, the health care professional can be reasonably assured that the proposed action falls within the scope of morally acceptable actions. However, if the proposed action fails any of these tests, the algorithm must be applied to another proposed action.

Ethical Dilemmas in Wilderness Medicine

With its unique setting and mode of practice, wilderness medicine provides practitioners with situations that are rarely seen by most other providers. These dilemmas can be grouped into three categories: standards of care, priority in care, and the decision-making process (Box 107-2). As might be expected, some of the issues in each group deal with provider–patient dilemmas, whereas others have more to do with group or governmental policies. These dilemmas have few parallels in other areas of medical practice (except perhaps battlefield medical practice or medical care during major disasters), resulting in ethical decisions that differ from those in standard medical settings. Such dilemmas include providing euthanasia for potentially nonfatal medical conditions, abandoning patients, and prioritizing medical care for original patients and rescue team members. However, the ethical decision-making process used to sort through these dilemmas is similar to that used in other settings; this is a basic truism sometimes obscured by the unique setting and issues of wilderness medical care. A limited discussion of these ethical dilemmas and the values involved follows.

BOX 107-2 Ethical Dilemmas in Wilderness Care

Standard-of-Care Dilemmas

Priority-in-Care Dilemmas

Standard-of-Care Dilemmas

Limited Resources

Although commercially available standardized medical kits are usually designed on the basis of medical criteria, it is vital to recognize that some types of treatment will be implicitly unavailable because of what is excluded from these kits. No one is expected to carry a fully stocked emergency department into the field, but clearly identifying the ethical dilemmas that are entailed in compiling these kits helps team members with their decisions. For example, if a decision to not carry antiarrhythmic medications or a defibrillator is made and if a team member suffers a cardiac rhythm abnormality, then there will be little that can be done for him or her. Some people may omit medical kit items that could be useful, such as intravenous solutions. As the medical person on one doomed expedition to the Himalayan peak Nanda Devi recalled, “[My] irritation grew as [I] remembered [being] pressured into leaving intravenous fluids behind.”22 Such pre-expedition resource decisions may jeopardize a team member. It helps if team members know in advance that these decisions were made and even participate in making them.

Giving Authority to Untrained Personnel

The following hypothetical case illustrates both the questions raised in this type of dilemma and the application of the Rapid Approach to Emergency Ethical Problems (see Figure 107-3). A backcountry excursion sets out with a medical provider who is unprepared for orthopedic emergencies. When a group member dislocates her shoulder, the provider is unwilling to go beyond his level of training by attempting shoulder relocation, although the victim (as well as the rest of the party) encourages the attempt. Another member of the party with even less training volunteers to attempt the maneuver; the clinician is then in a double bind, seemingly forced either to overextend his skills or to acquiesce to even less knowledgeable medical care for the victim.

Using step 3, the provider attempts to choose an action that is ethically acceptable (by applying the ideas found in Figure 107-2), even if it is not the optimal action that he or she might select if more time were available to consider the problem. Possible actions in this case might include attempting a reduction, allowing the layperson to attempt a reduction, simply immobilizing the victim’s shoulder, leaving the victim and going for help, or ignoring the situation and leaving the decision to someone else. The provider must first choose a course of action (remembering that not deciding is also a course of action) and then decide whether the choice falls within the scope of ethically acceptable behavior. For example, if the proposed action is shoulder immobilization, the three tests of impartiality (i.e., the Golden Rule), universalizability (i.e., “Should every practitioner do as I plan to do?”), and interpersonal justifiability (i.e., “Would I be ashamed to have my actions publicized?”) should be applied to this action. If the action passes all three tests, it is probably ethically acceptable and may be used. Remember that ethically acceptable actions may differ with the circumstances or the wilderness group involved.

Priority-in-Care Dilemmas

Triage Choices: Whom to Rescue First and How to Distribute Resources

Three ethical dilemmas result from wilderness triage questions that are unlikely to occur elsewhere (with the exception of battlefield settings).5 The first dilemma arises when the wilderness practitioner knows all the victims and may have personal ties to at least one. This is unlike normal triage scenarios and complicates any decision about who receives treatment, especially if resources are limited. For example, during an outbreak of giardiasis in a party of 12, the provider may have only enough metronidazole (Flagyl) to treat 5 people. Another more serious example would be a lightning strike in the midst of 6 people, with only one other individual capable of providing assistance. In each case, the medical practitioner applying triage criteria may be torn between medical and personal concerns.

An ethical dilemma also arises when a rescue team member is injured while out in the field. Should rescue teams treat their injured team member before, or instead of, other victims? Wilderness rescue is an inherently dangerous operation. Although the safety record of some organized and experienced rescue groups has been excellent, this is not universal, particularly with ad hoc rescue attempts.10 Where should the team’s priorities lie? Again, an analogy can be drawn with triage parameters in emergency care. The principle of triage is that, as long as resources are available, the most seriously injured are treated first. Those who cannot be saved with available resources or be evacuated in time to be saved are given only comfort measures. This situation logically and morally prevails in wilderness medical care. However, emotion rather than reason often influences actions, so the wilderness health care provider must ensure that ethical decision making prevails.

Issues of Survival

In some situations, the lives of expedition members may be put at immediate risk if an injured person receives optimal assistance. One well-known example is high-altitude climber Simon Yates, who, while trying to lower his injured climbing partner, Joe Simpson, down to base camp in the Peruvian Andes, found himself in a situation in which he had to either cut the lowering rope tethering his partner, almost assuredly killing him, or risk also dying himself.25 (He chose to cut the rope and, unbelievably, Simpson survived.)

In another example, a diver may surface too quickly and suffer an air embolism. Reviewing the ethical considerations in wilderness medicine’s ethical triangle (see Figure 107-2), both medical indications and possibly patient autonomy influence the decision to rapidly transport the victim to a recompression chamber. However, even with the medical urgency of the situation, the other divers’ safety mandates that the boat remain in the area until the other divers are on board. This example demonstrates again that, in the wilderness setting, security factors are primary when making ethical decisions.

Decision-Making Dilemmas

Euthanasia

Controversy continues to rage in society and medicine over the concept of active euthanasia (i.e., mercy killing). In wilderness medicine, however, euthanasia may be less ethically problematic, although it is a very sensitive issue to discuss and a devastating event for those involved. Active euthanasia may be an ethically acceptable alternative for the rare situation in which a patient will die either because he or she cannot be rescued from the wilderness environment or because the survival of group members would be jeopardized by attempting to evacuate or remain with him or her until help arrives. The seriously injured person on a high-altitude climb with inclement weather quickly approaching and the injured caver in a flooding cave are two examples. In these cases, euthanasia is based on the beneficence of relieving suffering in a doomed individual (although many in the medical profession believe that euthanasia violates professional principles), security for other members of the party (not creating more victims), and perhaps patient autonomy.2

Further complicating the preceding scenarios is the question of whether such patients should be simply left to die (i.e., passive euthanasia) or more humanely killed (i.e., active euthanasia). This question should be given serious consideration, because many incidents of passive euthanasia in wilderness settings occur, especially in high-risk or remote areas. For example, passive euthanasia has occurred several times on expeditions to Mt Everest when unconscious hypothermic climbers were left to die when conditions made it difficult or impossible to get them down.22 The ethical question of what is best for the injured individual almost always comes in direct conflict with other team members’ lack of confidence in their (or their medical person’s) prognosis and their unwillingness to implement active euthanasia. The lack of certainty about prognosis may sometimes be justified. For example, during a disastrous expedition to Mt Everest, a physician climber who was left for dead (active euthanasia was not discussed among team members) survived by eventually making it to camp on his own.

Dilemmas in Wilderness Policies

Ethical decision making plays a part in policies governing wilderness medicine. The values of beneficence and nonmaleficence make proposed and actual rules for wilderness medical practice untenable. These policies include when to stop searches, prohibition of motorized vehicles in wilderness areas, no-rescue areas, prohibition of environmental destruction, and restriction of medical providers’ roles (see Giving Authority to Untrained Personnel, earlier).

When to Stop Searches

Without a body or corpse, it is difficult for managers of wilderness searches to know when to stop searching for someone who is presumed lost. Resource-allocation decisions (i.e., distributive justice) create the contours of the solution to this kind of ethical dilemma. The parameters include available resources, probability of finding the lost person, danger to searchers, and the likelihood of survivability under existing conditions. An example of such a dilemma occurred near Mt Rainier, when a hunter briefly lost consciousness and became separated from his group. Fortunately, he was a strong, heavy man who could draw on fat stores for energy and warmth for several days. His hunting companions immediately began a search, followed by a formal search and rescue by a trained team the next morning. The dilemma was when to stop or pause the search because of bad weather, risks to the searchers, and the probability that the hunter was dead as a result of a preexisting heart condition. Severe weather did cause the search to be halted after 4 days because of danger to the searchers, but it was to resume the next day after the weather had cleared. Before the search could be resumed, however, the victim found his way to a road, where he encountered a ranger. As this case illustrates, searches will often last beyond the point at which the victim is believed to be dead in hopes of finding them alive or at least finding the corpse. It is the search leader’s responsibility to continue the search process as long as it is reasonable to do so.20

No-Rescue Areas

Perhaps the most pernicious concept proposed to govern wilderness medical care is that of the “no-rescue area,” into which adventurers would go with the foreknowledge that no rescue would be available.17 This is akin to playing Russian roulette: people entering these wilderness areas put life and limb at risk while society condones and presumably enforces a requirement to not assist those in need. All explorers pushing the envelope of what is possible have entered these areas. The first men in space, and certainly Neal Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, knew that rescue from the surface of the moon was not an option. The early mountaineers did not venture above 8000 m (26,247 feet) expecting a rescue if things went bad. Today, the space shuttle has a backup plan, and climbers have been rescued from the highest altitudes. Is it reasonable to designate areas and to pursue adventures where no rescue would be attempted or even contemplated?

Summary

Enjoying the wilderness and being capable and willing to provide care in remote settings fulfill many human desires. The challenges and decisions that sometimes need to be made can call an individual’s values into question and haunt the individual for a long time. Preparing for these situations by thoughtfully selecting medical equipment, seeking out additional skills, and having difficult conversations with participants before a trip occurs can be as important as physical training. Sometimes, despite thorough preparation, unforeseeable events happen, and the decision tools presented in the algorithm in Figure 107-3 can be helpful to the provider and patient.

1 Aquinas T: Two precepts of charity. 1273.

2 Backer HD. Wilderness medicine. In Iserson KV, Sanders AB, Mathieu D, editors: Ethics in emergency medicine, ed 2, Tucson, Ariz: Galen Press, 1995.

3 Buchanan AE. The question of competence. In Iserson KV, Sanders AB, Mathieu D, editors: Ethics in emergency medicine, ed 2, Tucson, Ariz: Galen Press, 1995.

4 Drane JF. Competency to give an informed consent: A model for making clinical assessments. JAMA. 1984;252:925.

5 Frisina ME. Ethical principles and the practice of battlefield health care. Military Chaplains’ Review. 1991;Spring:925.

6 Gauthier DP. Morals by agreement. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1986.

7 Iserson KV. An approach to ethical problems in emergency medicine. In Iserson KV, Sanders AB, Mathieu D, editors: Ethics in emergency medicine, ed 2, Tucson, Ariz: Galen Press, 1995.

8 Iserson KV. Bioethics. In Rosen P, Barkin RM, editors: Emergency medicine: Concepts and clinical practice, ed 4, St Louis: Mosby, 1998.

9 Iserson KV. Death to dust: What happens to dead bodies?, ed 2. Galen Press, Tucson, Ariz, 2001..

10 Iserson KV. Injuries in search and rescue volunteers: A 30-year experience. West J Med. 1989;151:352.

11 Iserson KV. Pediatric bioethics. In: Reisdorff EJ, Roberts MR, Wiegenstein JG, editors. Pediatric emergency medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1992.

12 Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ. Clinical ethics, ed 4. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998.

13 Kant I. Fundamental principles of the metaphysics of morals. 1785. Translation from]. Hutchins RM, editor. Kant: The great books. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1952.

14 Kauffman AJ, Putnam WL. K2: 1939 tragedy—the full story of the ill-fated Wiessner expedition. Seattle: The Mountaineers; 1992.

15 Landesman BM. Physician attitudes toward patients. In Iserson KV, Sanders AB, Mathieu D, editors: Ethics in emergency medicine, ed 2, Tucson, Ariz: Galen Press, 1995.

16 Lansing A. Shackelton’s valiant voyage. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1960.

17 McAvoy L, Dustin D. You’re losing your right to be alone. Backpacker. 1984;12:60.

18 Mill JS. Utilitarianism. London, 1861]. Hutchins RM, editor. The great books. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1952.

19 Nolan JR, Connolly MJ. Black’s law dictionary, ed 5. St Paul, Minn: West Publishing; 1979.

20 Nunn B. Panic rising: True life survivor tales from the great outdoors. Seattle, Wash: Sasquatch Books; 2003.

21 Philbrick N. In the heart of the sea: The tragedy of the whaleship Essex. New York: Penguin Putnam; 2000.

22 Roskelley J. Nanda Devi: The tragic expedition. Harrisburg, Penn: Stackpole Books; 1987.

23 Schloendorff v. Society of New York Hospital. 105 N.E. 92, 93. 1914.

24 Simpson AWB. Cannibalism and the common law: The story of the tragic last voyage of the Mignonette and the strange legal proceedings to which it gave rise. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1984.

25 Simpson J. Touching the void. London: Butler & Tanner; 1988.