chapter 6 The essence of good health

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

As community attitudes evolve, healthcare costs spiral and evidence accumulates, the community and general practitioners are steadily recognising the importance of moving towards more holistic and wellness-based models of healthcare. Models such as Dean Ornish’s lifestyle program for heart disease have been shown to significantly reduce costs while also leading to better therapeutic outcomes.1

Among the great advances in healthcare in the twentieth century were antibiotics, anaesthetics and immunisation, with the genetic revolution just beginning to gain momentum. Despite these significant discoveries, the greatest burden of illness in affluent countries is due to lifestyle-related illnesses.2 Cardiovascular disease is still the leading cause of death, followed closely by cancer. It is predicted that by 2030 depressive illnesses will be the leading burden of disease.3 The trends in obesity, inactivity, drug use and mental illness are far from encouraging, and the long-term impact of these determinants of health may be far greater than expected. They all interact synergistically to predispose towards illness; and conversely, positive strategies to enhance health also act synergistically.

THE ESSENCE MODEL

This chapter gives an outline of the ESSENCE model of healthcare. ESSENCE is a mnemonic:

The ESSENCE approach is a comprehensive framework to assist in the prevention and management of illness as well as promoting wellness. It is holistic in its focus, designed to complement conventional medical care and is eminently applicable to the primary care setting.4 ESSENCE has been the basis for the Health Enhancement Program (HEP) taught as core curriculum for all medical students at Monash University, Melbourne. It serves to enhance the personal wellbeing of the practitioner as well as to foster patient wellbeing and provide clinical knowledge and skills.5

For lifestyle interventions to be optimally effective, a structured, systematic and comprehensive approach to dealing with a range of relevant variables needs to be used. This helps the planning, implementation and evaluation of lifestyle and healthcare plans. This chapter gives an overview of the model and its relevance to a condition such as cardiovascular disease, and illustrates its application to a case of multiple sclerosis.

EDUCATION

In the conventional sense, education is also protective of health, and a lack of formal education by itself is a risk factor for poor health.9 Indeed, one of the most powerful ways to improve health in developing countries is to improve literacy rates among women.

STRESS MANAGEMENT

In the ESSENCE model, ‘stress’ refers not just to stress in the common sense of the word, but also mental health in the broadest sense. Good mental health is central to being able to make and maintain other lifestyle improvements. This is illustrated in the Ornish lifestyle program for heart disease, in which stress management was the vital factor in ensuring that all the other lifestyle factors could be implemented and maintained.1,10 We well know that making healthy lifestyle changes while stressed, anxious or depressed is difficult, if not impossible.

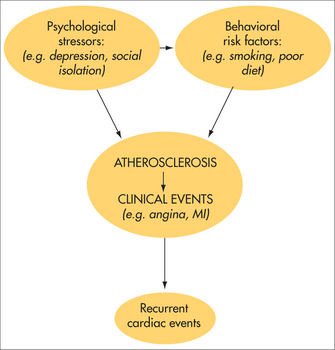

Mental health has a profound and direct effect upon physical health and recovery from illness. To illustrate, it is well known that depression is a major independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (Fig 6.1)11—chronic severe depression increases the risk of cardiovascular disease fivefold—but less well known is the evidence that the addition of a comprehensive psychologically based stress-management plan to conventional cardiac rehabilitation nearly halves the risk of subsequent cardiac events.12 One effective stress-management program reduced cardiac events by 74% over a 5-year follow-up compared with usual care alone.13 So improving mental health is important for quality of life, to facilitate other healthy lifestyle changes and for its direct physiological health benefits.

SPIRITUALITY

The influence of spirituality on health is not always easy to determine, and yet evidence clearly points to it having an important role in the prevention and management of a range of psychological and physical diseases14,15 as well as helping the individual to cope, especially with chronic and life-threatening disease.16

Although some doctors may believe that spirituality is not the domain of the medical practitioner, evidence suggests that approximately 80% of patients wish to discuss spiritual matters with their doctors in certain circumstances, such as when confronting a life-threatening illness.17 If doctors are to incorporate spiritual and religious issues where the need arises, then patient-appropriate language, an attitude of cultural and religious tolerance, and appropriate referral sources, will be essential in underpinning that conversation. These issues will be discussed in more depth in the chapter on spirituality (Ch 12).

EXERCISE

Exercise in itself is a therapeutic tool18 and lack of exercise ranks second to smoking as a cause of disability and death in Australia.19 There is an enormous amount of evidence on the beneficial effects of exercise in preventing and managing virtually any condition, and yet exercise is not a central part of the management plan as often as it should be. Obviously the type, duration and intensity of exercise needs to be tailored to an individual’s needs, tastes, health and abilities.

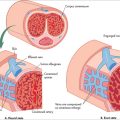

The important role of exercise can be illustrated using an example of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Apart from reducing all-cause mortality,20 regular exercise also decreases disease-specific mortality from CVD.21–23 This is through a variety of effects, such as improvements in lipid profile, reduced thrombogenesis, improvement in insulin resistance and reduction of blood pressure. If exercise is prescribed for CVD it has positive side effects, such as benefits for osteoporosis and diabetes,24 and reduced cancer risk (including lung, colon, breast and prostate).25–27 Exercise also has an important role in mental health for old and young—for example, it is therapeutic for depression28 and anxiety.29 These issues will also be explored in a subsequent chapter.

NUTRITION

Deficient diets are a more major source of illness than tends to be acknowledged in medical education and this no doubt is reflected in clinical practice. Carefully chosen supplements may play a role in some circumstances, but they are not a replacement for a healthy diet. For example, beta-carotene supplements are probably not effective in preventing cancer,30 whereas beta-carotene-rich foods are.31,32 Research has shown that:

Women in the highest quartile of plasma total carotenoid concentration (marker of intake of vegetables and fruit) had significantly reduced risk for a new breast cancer event (HR 0.57) [that is, a 43% reduction in risk of recurrence].33

and that:

Vegetable and, particularly, fruit consumption contributed to the decreased risk … These results indicate the importance of diet, rather than supplement use, in concert with endogenous antioxidant capabilities, in the reduction of breast cancer risk.34

A similar picture is seen in CVD. Fish oils, due to their high concentration of omega-3 fatty acids, for example, produce benefits for triglyceride35 and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) profiles,36 prevention of arrhythmias,37,38 reduction of blood pressure39 and reduction of atherogenesis,40 and they have antithrombotic and antiplatelet activity.

For the greater part of clinical practice, the dietary advice given by doctors tends to be non-specific. Perhaps this is a reflection of the level of attention given to the topic in medical education and literature, but if the effects attributable to healthy nutrition were attributable to a pharmaceutical product, then a doctor would probably be negligent in not knowing about it in detail and prescribing it widely. The important role of nutrition will also be explored in Chapter 10.

CONNECTEDNESS

‘Connectedness’ or social support is important at any age or situation in life. For children and adolescents, connectedness at home and at school is strongly protective against comorbidities such as depression, suicide, drug and alcohol abuse, teenage pregnancy, crime and violence.41 The presence of ‘functional relationships’ is associated with a better recovery from depression. Social marginality or isolation has been shown to predispose to heart disease, cancer, depression, hypertension, arthritis, schizophrenia, tuberculosis and overall mortality.42 All-cause mortality in socially isolated males was 2–3 times higher and in women was 1.5 times higher over a 12-year follow-up than in people who were more socially connected.43 With regard to heart disease, socioeconomic and occupational factors are independent risk factors,44,45 but even when a person has well-established heart disease, their social context has a profound effect on recovery. There was a fourfold increased in the death rate following acute myocardial infarction (AMI) for people who were socially isolated and experiencing high levels of stress.46 Those over 65 years of age were three times more likely to die following an AMI if they had poor social support, as measured by the simple question: ‘Can you count on anyone to provide you with emotional support (talking over problems or helping you to make a difficult decision)?’47 So connectedness plays an important role in the prevention and management of any disease and at any stage of the life cycle. The GP is well placed to provide emotional support, to encourage patients to seek out sources of social support, and in some settings to facilitate support in the form of support groups.

ENVIRONMENT

‘Environment’ means much more than air, water and earth, as important as these are. It includes the number and types of chemicals we are exposed to, domestically and occupationally. It includes the radiation and electromagnetic fields to which we are exposed.48 Importantly, it includes the social and sensory environment we create for ourselves. An overly noisy medical environment, for example, is associated with poorer health and higher stress.49

Sunlight can play both a positive and a negative role for health, depending on the amount and type of sun exposure. Although sunburn increases the incidence of malignant melanoma, regular moderate doses of sunlight help to reduce the incidence of a range of illnesses including depression, heart disease, a number of cancers including melanoma, multiple sclerosis and osteoporosis, to name a few.50

USING ESSENCE IN PRACTICE

CASE STUDY

Helen is a 37-year-old woman with a past history of multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosed when she was 32 years old. She has recently moved from interstate with her husband and two children and now presents to you with a view to finding a new GP. At the initial consultation you find that she has only mild ongoing neurological impairment by way of some weakness in her left leg and numbness in the right leg. She is interested in taking an active part in the management of her MS and wants to take a holistic approach to her illness.51 You encourage her in her endeavour and make a long appointment for next week for her to come back to discuss the ESSENCE approach. In the meantime you explore further background information about lifestyle factors and MS to help inform yourself more fully. At the follow-up consultation you discuss the following issues with her.

Education

You provide the patient with education in the following information and self-help strategies, as well as by suggesting a readable and authoritative text on the subject of lifestyle factors and MS.52

Stress management

Psychological health has a significant impact on the progression of MS and on how a person copes with it.53–55 You inform Helen about the basic principles of how stress affects immune function and autoimmune conditions, and suggest that stress management is a vital part of improving psychological wellbeing and of assisting her in making and maintaining other lifestyle changes. Helen expresses interest in joining the evening stress management classes being held in your practice.

Exercise

For MS patients, regular exercise can increase general fitness and strength, reduce disability,56 improve mood and coping, reduce the number of falls and fractures, enhance social interaction and improve immune function. You discuss and agree on an ‘exercise prescription’, which includes attending her local fitness centre and walking regularly with her husband, in the morning and late afternoon sun where possible. You also encourage Helen to explore the MS Society’s hydrotherapy program.

Nutrition

Studies of dietary interventions for the management of MS57–59 have suggested that MS patients on a low-fat diet (less than 20 g/day) may have lower death rates, disability and numbers of MS exacerbations than those not on a low-fat diet. Supplements with omega-3 fatty acids may also be associated with significant reductions in the frequency and severity of relapses.60 Fish and flaxseed oils, high in omega-3 fatty acids, have significant anti-inflammatory properties in a range of conditions including MS, and fish oils are also an excellent source of vitamin D. Vitamin D enhances immune function, and seems to reduce the incidence and progression of MS.61 Potentially protective nutrients for MS patients include vegetable protein, dietary and cereal fibre, other vitamins (C, thiamin and riboflavin), calcium and potassium.62 You inform Helen of these findings, and she is keen to start including these dietary changes in her diet and will also explore using some selected dietary supplements under your guidance.

Connectedness

Stressful life events and an unsupportive social life are associated with the onset and exacerbation of a variety of autoimmune diseases.63 Helen says that she gets great support from her family, although moving interstate has been a source of potential concern. She also finds that going to the MS Society has given her great support and that attending the hydrotherapy classes will enhance this even further.

Environment

Countries with lower levels of sunshine have significantly higher incidences of MS. Within countries, those regions with more sunlight also have a substantially lower incidence.64,65 The progression of MS over an 11-year period was nearly halved (odds ratio (OR) 0.53) for those with higher residential sun exposure.66 High residential exposure and occupational exposure combined was associated with an OR of 0.24, that is, a quarter chance of dying over that 11-year period compared to those with low sun exposure. The benefits of sunlight may be due to the direct effects of sunlight on immune function, melatonin levels67 and vitamin D.68 Helen says that she has tended to avoid sunshine and will make an effort to get at least 20 minutes of sun exposure daily and that linking it to her exercise times will be a sensible way of doing that.

1 Ornish D, Brown SE, Scherwitz LW, et al. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? Lancet. 1990;336:129-133.

2 Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1747-1757.

3 Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442.

4 Hassed C. The ESSENCE of healthcare. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34(11):957-960.

5 Hassed C, de Lisle S, Sullivan G, et al. Enhancing the health of medical students: outcomes of an integrated mindfulness and lifestyle program. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(3):387-398.

6 Lehrer PM, Sargunaraj D, Hochron S. Psychological approaches to the treatment of asthma. J Consult Clinical Psychol. 1992;60(4):639-643.

7 Syme SL, Balfour JL. Explaining inequalities in coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1997;350(9073):231-232.

8 Syme SL. Mastering the control factor. The Health Report, ABC Radio. Health Report transcript. Online. Available: www.abc.net.au/rn, 9 November 1998.

9 Eckert JK, Rubinstein RL. Older men’s health. Sociocultural and ecological perspectives. Med Clin North Am. 1999;83(5):1151-1172.

10 Ornish D, Scherwitz L, Billings J, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1998;280:2001-2007.

11 Bunker SJ, Colquhoun DM, Esler MD, et al. ‘Stress’ and coronary heart disease: psychosocial risk factors. Med J Aust. 2003;178(6):272-276.

12 Linden W, Stossel C, Maurice J. Psychosocial interventions for patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Int Med. 1996;156(7):745-752.

13 Blumenthal J, Jiang W, Babyak MA, et al. Stress management and exercise training in cardiac patients with myocardial ischaemia. Arch Int Med. 1997;157:2213-2223.

14 Koenig HG. Religion and medicine II: religion, mental health, and related behaviors. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2001;31(1):97-109.

15 Townsend M, Kladder V, Ayele H, et al. Systematic review of clinical trials examining the effects of religion on health. South Med J. 2002;95(12):1429-1434.

16 Sullivan MD. Hope and hopelessness at the end of life. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(4):393-405.

17 McCord G, Gilchrist VJ, Grossman SD, et al. Discussing spirituality with patients: a rational and ethical approach. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(4):356-361.

18 Bauman A. Updating the evidence that physical activity is good for health: an epidemiological review 2000–2003. J Sci Med Sport. 2004;7(1 Suppl):6-19.

19 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Heart, stroke and vascular diseases—Australian facts 2001. National Heart Foundation of Australia, National Stroke Foundation of Australia (Cardiovascular Disease Series No 14). AIWH Cat. No. CVD 13. Canberra: AIWH, 2001.

20 Kampert J, Blair S, Barlow C, et al. Physical activity, fitness and all cause and cancer mortality. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:542-547.

21 Maiorana A, O’Driscoll G, Cheetham C, et al. Combined aerobic and resistance exercise training improves functional capacity and strength in CHF. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:1565-1570.

22 Berlin J, Colditz G. A meta-analysis of physical activity in the prevention of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:612-628.

23 Tanasescu M, Leitzmann MF, Rimm EB, et al. Exercise type and intensity in relation to coronary heart disease in men. JAMA. 2002;288:1994-2000.

24 Helmrich S, Ragland D, Paffenbarger R. Prevention of non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus with physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26:649-660.

25 Colditz G, Cannuscio C, Grazier A. Physical activity and reduced risk of colon cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:649-667.

26 Thune I, Lund E. The influence of physical activity on lung cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 1997;70:57-62.

27 Friedenreich CM, McGregor SE, Courneya KS, et al. Case-control study of lifetime total physical activity and prostate cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(8):740-749.

28 Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, Kampert JB, et al. Exercise treatment for depression. Efficacy and dose response. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(1):1-8.

29 Byrne A, Byrne DG. The effect of exercise on depression, anxiety and other mood states: a review. J Psychosom Res. 1993;13(3):160-170.

30 Hennekens CH, et al. Lack of effect of long-term supplementation with beta carotene on the incidence of malignant neoplasms and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(18):1145-1149.

31 Omenn GS, Goodman GE, Thornquist MD, et al. Effects of a combination of beta carotene and vitamin A on lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(18):1150-1155.

32 Shekelle RB, Lepper M, Liu S, et al. Dietary vitamin A and the risk of cancer in the Western Electric study. Lancet. 1981;2(8257):1186-1190.

33 Rock CL, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, et al. Plasma carotenoids and recurrence-free survival in women with a history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(27):6631-6638.

34 Ahn J, Gammon MD, Santella RM, et al. Associations between breast cancer risk and the catalase genotype, fruit and vegetable consumption, and supplement use. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(10):943-952.

35 Jeppesen J, Hein HO, Suadicani P, et al. Triglyceride concentration and ischemic heart disease: an eight-year follow up in the Copenhagen Male Study. Circulation. 1998;97(11):1029-1036.

36 Vanschoonbeek K, de Maat MP, Heemskerk JW. Fish oil consumption and reduction of arterial disease. Nutrition. 2003;133:657-660.

37 de Lorgeril M, Salen P. Alpha-linolenic acid and coronary heart disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2004;14(3):162-169.

38 McLennan PL, Abeywardena MY, Charnock JS. Dietary fish oil prevents ventricular fibrillation following coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion. Am J Heart. 1988;116(3):709-717.

39 Geleijnse JM, Grobbee DE. Blood pressure response to fish oil supplementation: meta regression analysis of randomised trials. J Hypertension. 2002;20(8):1493-1499.

40 von Schacky C. The role of omega-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular disease. Curr Atherocler Rep. 2003;5(2):139-145.

41 Resnick MD, Bearman P, Blum R, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm; findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278(10):823-832.

42 Pelletier K. Mind–body health: research, clinical and policy applications. Am J Health Promot. 1992;6(5):345-358.

43 House J, Landis K, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540-545.

44 Lantz PM, House JS, Lepkowski JM, et al. Socioeconomic factors, health behaviours, and mortality: results from a nationally representative prospective study of US adults. JAMA. 1998;279(21):1703-1708.

45 North FM, Syme SL, Feeney A, et al. Psychosocial work environment and sickness absence among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(3):332-340.

46 Ruberman W, Weinblatt E, Goldberg JD, et al. Psychosocial influences on mortality after AMI. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:552-559.

47 Berkman LF, Leo-Summers L, Horwitz RI. Emotional support and survival after AMI: a prospective, population-based study of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:1003-1009.

48 Henshaw DL. Does our electricity distribution system pose a serious risk to public health? Med Hypotheses. 2002;59(1):39-51.

49 Topf M. Hospital noise pollution: an environmental stress model to guide research and clinical interventions. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(3):520-528.

50 Hassed C. Are we living in the dark ages? The importance of sunlight. Aust Fam Physician. 2002;31(11):1039-1041.

51 Jelinek G, Hassed CS. Managing multiple sclerosis in primary care: are we forgetting something? Qual Prim Care. 2009;17(1):55-61.

52 Jelinek G. Taking control of multiple sclerosis. Melbourne: Hyland House, 2000.

53 Mohr DC, Hart SL, Julian L, et al. Association between stressful life events and exacerbation in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. BMJ. 2004;328(7442):731. Epub 19 March 2004.

54 Martinelli V. Trauma, stress and multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2000;21(4 Suppl 2):S849-S852.

55 Ackerman KD, Stover A, Heyman R, et al. Relationship of cardiovascular reactivity, stressful life events, and multiple sclerosis disease activity. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17(3):141-151.

56 Patti F, Ciancio MR, Cacopardo M, et al. Effects of a short outpatient rehabilitation treatment on disability of multiple sclerosis patients—a randomised controlled trial. J Neurol. 2003;250(7):861-866.

57 Swank RL, Dugan BB. Effect of low saturated fat diet in early and late cases of multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1990;336(8706):37-39.

58 Swank RL. Multiple sclerosis: fat–oil relationship. Nutrition. 1991;7(5):368-376.

59 Swank RL, Goodwin JW. How saturated fats may be a causative factor in multiple sclerosis and other diseases. Nutrition. 2003;19(5):478.

60 Nordvik I, Myhr KM, Nyland H, et al. Effect of dietary advice and omega-3 supplementation in newly diagnosed MS patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2000;102(3):143-149.

61 Hayes CE. Vitamin D: a natural inhibitor of multiple sclerosis. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59(4):531-535.

62 Ghadirian P, Jain M, Ducic S, et al. Nutritional factors in the aetiology of multiple sclerosis: a case control study in Montreal, Canada. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:845-852.

63 Homo-Delarche F, Fitzpatrick F, Christeff N, et al. Sex steroids, glucocorticoids, stress and autoimmunity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1991;40(4–6):619-637.

64 O’Reilly MA, O’Reilly PM. Temporal influences on relapses of multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol. 1991;31(6):391-395.

65 McMichael AJ, Hall AJ. Does immunosuppressive ultraviolet radiation explain the latitude gradient for multiple sclerosis? Epidemiology. 1997;8:642-645.

66 Freedman DM, Dosemeci M, Alavanja MC. Mortality from multiple sclerosis and exposure to residential and occupational solar radiation: a case-control study based on death certificates. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57(6):418-421.

67 Hutter CD, Laing P. Multiple sclerosis: sunlight, diet, immunology and aetiology. Med Hypotheses. 1996;46(2):67-74.

68 Green MH, Petit-Frere C, Clingen PH, et al. Possible effects of sunlight on human lymphocytes. J Epidemiol. 1999;9(6 Suppl):S48-S57.