Chapter 25 The epidemiology of obstetrics

MATERNAL MORTALITY

A maternal death is defined by the International Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death (ICD-10) as the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days after abortion, miscarriage or delivery that are due to direct or indirect maternal causes. These deaths are divided into direct, indirect, late and incidental (Box 25.1). The maternal mortality rate is the number of such deaths per 100 000 maternities.

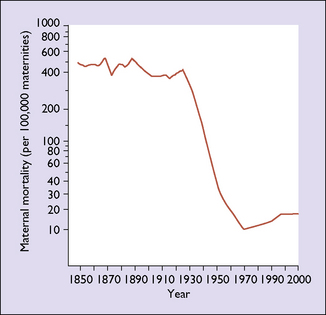

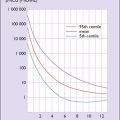

In most developed countries the maternal death rate remained about the same from 1850 to 1934, when it began to fall. In the period before the mid-1930s it was about 500 per 100 000; by the mid-1980s, in many industrialized countries it had fallen to fewer than 10 per 100 000 maternities (Fig. 25.1). The initial fall was due to the control of infections by better obstetric care and the introduction of antibiotics. The second factor was that most women availed themselves of good-quality antenatal care, which enabled complications to be detected early and treatment to be offered, usually in well-equipped hospitals staffed by trained medical attendants. Blood became increasingly and quickly available from blood banks, which considerably reduced the deaths due to haemorrhage. Sociological changes have also occurred in the past 60 years: fewer women now have more than three children, and most have their pregnancies before the age of 35. Higher parity and advancing age increase the risk of maternal death. There has been a small rise in the maternal mortality rates in some developed countries in the last decade. Whether this is due to women with medical conditions that previously precluded pregnancy having children, increasing maternal age, the rise in obesity or better ascertainment of cases is not clear.

Causes of maternal death

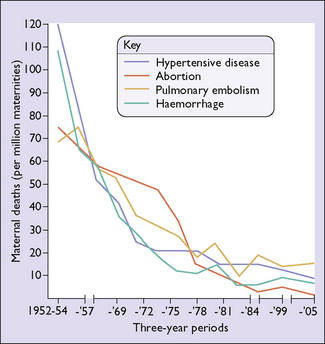

These reports have been published in the UK since 1952 and in Australia since 1965. The total direct and indirect deaths per 100 000 maternities had risen from 9.83 in the 1985–7 triennium to 12.45 in 2003–5. This may be due to underreporting in earlier years, but emphasizes that there is no room for complacency in modern maternity units in the developed world. The major contributing factors to suboptimal care are poor liaison between healthcare professionals, failure to appreciate the severity of the condition, and wrong diagnosis. Table 25.1 shows the most common causes of death, Table 25.2 the percentage associated with substandard care, and Figure 25.2 illustrates the changes with time in the major causes of maternal death in England and Wales. Maternal deaths can be reduced further, particularly those associated with anaesthesia, ectopic gestation, sepsis and pulmonary embolism.

Table 25.1 Major causes of maternal deaths per million maternities in the UK 1985–2005

| CAUSE | DEATHS |

|---|---|

| Direct | |

| Thrombosis and thromboembolism | 14–22 |

| Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia | 7–12 |

| Haemorrhage | 3–9 |

| Amniotic fluid embolus | 4–8 |

| Early pregnancy (ectopic and miscarriage) | 5–8 |

| Sepsis | 4–9 |

| Anaesthetic | 1–3 |

| Indirect | |

| Cardiac | 8–23 |

| Psychiatric | 4–9 |

| Malignancies | 3–5 |

| Coincidental | 12–26 |

| Late | 10–40 |

Table 25.2 Direct and indirect maternal deaths United Kingdom 2003–2005 assessed as having substandard care

| CAUSE OF DEATH | % WITH SUBSTANDARD CARE |

|---|---|

| Direct | |

| Thromboembolism | 56 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 67 |

| Cerebral embolism | 13 |

| Pre-eclampsia/eclampsia | 72 |

| Haemorrhage | 59 |

| Amniotic fluid embolism | 41 |

| Early pregnancy | 79 |

| Sepsis | 78 |

| Anaesthetic | 100 |

| All direct | 64 |

| Late direct | 55 |

| Indirect | |

| Cardiac | 46 |

| Psychiatric | 42 |

| Malignancy | 50 |

PERINATAL MORTALITY

Before perinatal mortality can be discussed, some terms need to be clarified.

Perinatal death is a stillbirth (or fetal death) or neonatal death

The definitions of the mortality rates and ratios is summarized in Box 25.2. For international comparison the WHO perinatal mortality rate refers to all births of at least 1000 g birthweight or when the birthweight is unknown, of at least 28 weeks’ gestation and neonatal deaths occurring within 7 days of birth. In many developed nations the PMR is around 6 per 1000 births. In the few developing countries that have been able to publish reasonably reliable data the PMR is between 35 and 55 per 1000 births.

Social factors affecting the PMR

Analysis of perinatal mortality

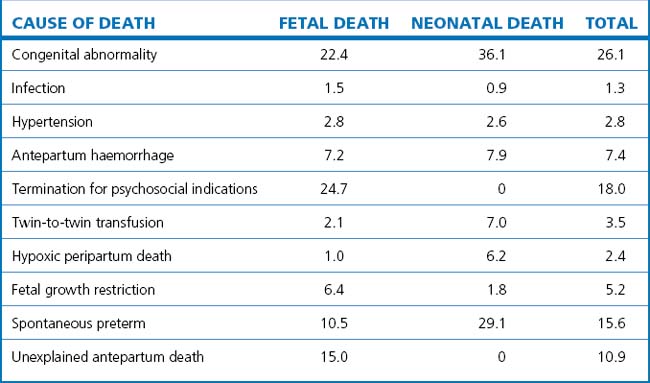

Perinatal deaths are classified according to their aetiology and not by the immediate cause of death. The accurate determination of the specific factors leading to the neonatal death enables health professionals to identify correctable problems. The principal causes of perinatal deaths in Victoria, Australia are shown in Table 25.3.

MANAGEMENT OF FETAL INTRA-UTERINE DEATH

Management

If spontaneous labour has not started 3 weeks after the diagnosis, or if the woman chooses immediate treatment, labour is induced by prostaglandin E2 vaginal pessaries or gel, as described on page 189. Alternatives are to prescribe mifepristone 600 mg/day for 3 days, misoprostol 100–200 μg 12-hourly for four doses, or the prostaglandin analogue sulprostone, 1 μg/min IV, until the fetus is expelled. Using any of these methods, 50% of women will expel the fetus in 12 hours and 90% in 24 hours.

Investigations

The basic investigations to determine the cause of death that should be offered are listed in Box 25.3. An autopsy should be offered, as the reason for the death is changed by the autopsy findings in up to 25% of cases. The findings can have significant implications for counselling and for the management of another pregnancy.