Chapter 10 The endocrine system

The endocrine history

Presenting symptoms (Table 10.1)

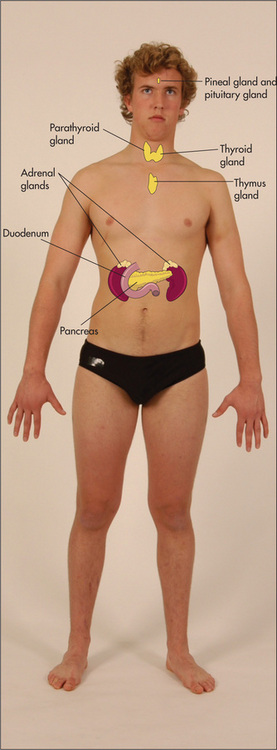

Hormones control so many aspects of body function that the manifestations of endocrine disease are protean. Symptoms can include changes in body weight, appetite, bowel habit, hair distribution, pigmentation, sweating, height and menstruation, galactorrhoea (unexpected breast-milk production—in men and women), as well as polydipsia, polyuria, lethargy, headaches and loss of libido and erectile dysfunction. Many of these symptoms have other causes as well and must be carefully evaluated. On the other hand, the patient may know which endocrine organ or group of endocrine organs has been causing a problem. In particular, there may be a history of a thyroid condition or diabetes mellitus. A list of common symptoms associated with various endocrine diseases is presented in Table 10.1. In this section some of the important symptoms associated with endocrine disease will be discussed.

| Major symptoms |

Changes in sweating

Increased sweating is characteristic of hyperthyroidism, phaeochromocytoma, hypoglycaemia and acromegaly, but may also occur in anxiety states and at the menopause (page 411).

Changes in hair distribution

Hirsutism refers to an increased growth of body hair in women. The clinical evaluation and differential diagnosis are presented on page 315. The absence of facial hair in a man suggests hypogonadism, while temporal recession of the scalp hair in women occurs with androgen excess. The decrease in adrenal androgen production that occurs as a result of hypogonadism, hypopituitarism or adrenal insufficiency can cause loss of axillary and pubic hair in both sexes.

Lethargy

This common symptom can be due to a number of different diseases. Patients with hypothyroidism, Addison’s disease and diabetes mellitus can present with this problem. Anaemia, connective tissue diseases, chronic infection (e.g. HIV, infective endocarditis), drugs (e.g. sedatives, diuretics causing electrolyte disturbances), chronic liver disease, renal failure and occult malignancy may also result in lethargy. Importantly, depression is a common cause of this symptom (page 411).

Changes in pigmentation

Increased pigmentation may be reported in primary adrenal insufficiency, Cushing’s syndrome or acromegaly. Decreased pigmentation occurs in hypopituitarism. Localised depigmentation is characteristic of vitiligo, which may be associated with certain endocrine diseases such as Hashimoto’sa disease with hypothyroidism and Addison’s disease with adrenal insufficiency as well as other auto-immune conditions.

Changes in stature

Tallness may occur in children for constitutional reasons (tall parents) or, rarely, may reflect growth hormone excess (leading to gigantism), gonadotrophin deficiency, Klinefelter’s syndromeb, Marfan’s syndrome or generalised lipodystrophy. Short stature can also result from endocrine disease, as discussed on page 313.

Menstruation

Failure to menstruate is termed amenorrhoea.

Apparent primary amenorrhoea can also occur if menstrual flow cannot escape: for example, if there is an imperforate hymen.

Past history

Patients with diabetes mellitus have an important chronic condition (Questions box 10.7, page 316). Treatment may be with diet, insulin or oral hypoglycaemic agents. One must determine how well the patient understands the condition, and whether he or she understands the principles of the diabetic diet and adheres to it. Find out how the blood sugar levels are monitored and whether or not the patient adjusts the insulin dose. Most patients should now be able to monitor their own blood sugar levels at home using a glucometer. There is now good evidence that tight control of blood sugar levels reduces the incidence of diabetic complications. Patients should have records of home blood sugar measurements, and may know the results of tests such as the haemoglobin A1c (a measure of average blood sugar levels) and of tests of renal function and for protein in the urine.

The endocrine examination

A formal examination of the whole endocrine system is set out on page 322. Usually there will be some clue from the history and general inspection to indicate what specific endocrine diseases should be pursued.

The thyroid

The thyroid glandc

Examination anatomy

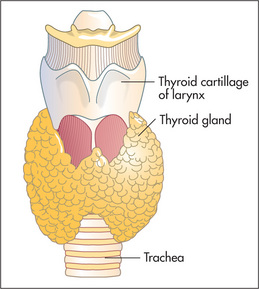

Even when it is not enlarged, the thyroid (Figure 10.2) is the largest

endocrine gland. Enlargement is common, occurring in 10% of women and 2% of men and more commonly in iodine-deficient parts of the world. The normal gland lies anterior to the larynx and trachea and below the laryngeal prominence of the thyroid cartilage. It consists of a narrow isthmus in the middle line (anterior to the second to fourth tracheal rings and 1.5 cm in size), and two larger lateral lobes each about 4 cm long. Although the position of the larynx varies, the thyroid gland is almost always about 4 cm below the larynx.

Inspection

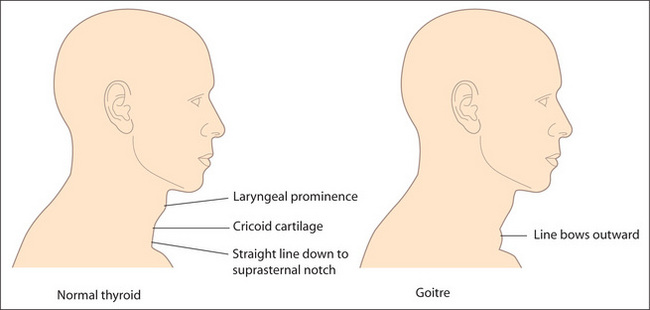

The normal thyroid may be just visible below the cricoid cartilage in a thin young person (Table 10.2).1,2. Usually only the isthmus is visible as a diffuse central swelling. Enlargement of the gland, called a goitre (Latin guttur, ‘throat’), should be apparent on inspection (see Good signs guide 10.1), especially if the patient extends the neck. Look at the front and sides of the neck and decide whether there is localised or general swelling of the gland. In normal people the line between the cricoid cartilage and the suprasternal notch should be straight. An outward bulge suggests the presence of a goitre (Figure 10.3). Remember that 80% of people with a goitre are biochemically euthyroid, 10% are hypothyroid and 10% are hyperthyroid.

| Midline |

* Aulus Celsus (page 297), the Roman medical writer who was active early in the 1st century AD, was the first to publish work distinguishing a goitre from cervical lymphadenopathy.

GOOD SIGNS GUIDE 10.1 Detection of a goitre (compared with ultrasound findings)

| Sign | Positive LR | Negative LR* |

| No goitre on inspection or palpation | 0.4 | — |

| Goitre palpated and visible only on neck extension | NS | — |

| Goitre palpated and visible with neck in normal position | 26.3 | — |

NAS = not significant.

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

Figure 10.3 The thyroid and goitre

Adapted from McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edition, St Louis, Saunders, 2007.

The temptation to begin touching a swelling as soon as it has been detected should be resisted until a glass of water has been procured. The patient takes sips from this repeatedly so that swallowing is possible without discomfort. Ask the patient to swallow, and watch the neck swelling carefully. Only a goitre or a thyroglossal cyst, because of attachment to the larynx, will rise during swallowing. The thyroid and trachea rise about 2 cm as the patient swallows; they pause for half a second and then descend. Some non-thyroid masses may rise slightly during swallowing but move up less than the trachea and fall again without pausing. A thyroid gland fixed by neoplastic infiltration may not rise on swallowing, but this is rare. Swallowing also allows the shape of the gland to be seen better.

Inspect the skin of the neck for scars. A thyroidectomy scar forms a ring around the base of the neck in the position of a high necklace. Also look for prominent veins. Dilated veins over the upper part of the chest wall, often accompanied by filling of the external jugular vein, suggest retrosternal extension of the goitre (thoracic inlet obstruction). Rarely, redness of the skin over the gland occurs in cases of suppurative thyroiditis.

Palpation

Palpation is best begun from behind (Figure 10.4) but warn the patient. Both hands are placed with the pulps of the fingers over the gland. The patient’s neck should be slightly flexed so as to relax the sternomastoid muscles. Feel systematically both lobes of the gland and its isthmus.

| 1 Carcinoma (5% of palpable nodules)—fixed to surrounding tissues, palpable lymph nodes, vocal cord paralysis, hard, larger than 4 cm (most are, however, smaller than this) |

| 2 Adenoma—mobile, no local associated features |

| 3 Big nodule in a multinodular goitre—palpable multinodular goitre |

Repeat the assessment while the patient swallows

Palpate the cervical lymph nodes (page 228). These may be involved in carcinoma of the thyroid.

Move to the front. Palpate again. Localised swellings may be more easily defined here. Note the position of the trachea, which may be displaced by a retrosternal gland.

Pemberton’s sign

Ask the patient to lift both arms as high as possible. Wait a few moments, then search the face eagerly for signs of congestion (plethora) and cyanosis. Associated respiratory distress and inspiratory stridor may occur. Look at the neck veins for distension (venous congestion). Ask the patient to take a deep breath in through the mouth and listen for stridor. This is a test for thoracic inlet obstruction due to a retrosternal goitre or any retrosternal mass.3 (Lifting the arms up pulls the thoracic inlet upward so that the goitre occupies more of this inflexible bony opening.)

Examination of the thyroid should be part of every routine physical examination. Causes of a goitre are listed in Table 10.4.

| Causes of a diffuse goitre (patient often euthyroid) |

| Causes of a solitary thyroid nodule |

Hyperthyroidism (thyrotoxicosis)

This is a disease caused by excessive concentrations of thyroid hormones. The cause is usually overproduction by the gland but may sometimes be due to accidental or deliberate use of thyroid hormone (thyroxine) tablets; thyrotoxicosis factitia. Thyroxine is sometimes taken by patients as a way of losing weight. The cause may be apparent in these cases if a careful history is taken (Questions box 10.1). The anti-arrhythmic drug amiodarone which contains large quantities of iodine can cause thyrotoxicosis in up to 12% of patients in low-iodine-intake areas.

Questions box 10.1

Questions to ask the patient with suspected hyperthyroidism

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

Many of the clinical features of thyrotoxicosis are characterised by signs of sympathetic nervous system overactivity such as tremor, tachycardia and sweating. The explanation is not entirely clear. Catecholamine secretion is usually normal in hyperthyroidism; however, thyroid hormone potentiates the effects of catecholamines, possibly by increasing the number of adrenergic receptors in the tissues.

The commonest cause of thyrotoxicosis in young people is Graves’ disease,d an autoimmune disease where circulating immunoglobulins stimulate thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) receptors on the surface of the thyroid follicular cells.

Examine a suspected case of thyrotoxicosis as follows (see Good signs guide 10.2).

| Sign | Positive LR | Negative LR |

| Pulse | ||

| ≥90/min | 4.4 | 0.2 |

| Skin | ||

| Moist and warm | 6.7 | 0.7 |

| Thyroid | ||

| Enlarged | 2.3 | 0.1 |

| Eyes | ||

| Eyelid retraction | 31.5 | 0.7 |

| Lid lag | 17.6 | 0.8 |

| Neurological | ||

| Fine tremor | 11.4 | 0.3 |

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

General inspection

Look for signs of weight loss, anxiety and the frightened facies of thyrotoxicosis.

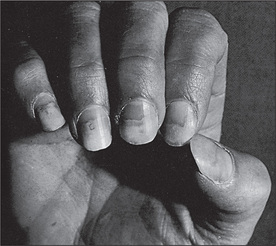

The hands

Look at the nails for onycholysis (Plummer’se nails) (Figure 10.6). Onycholysis (where there is separation of the nail from its bed) is said to occur particularly on the ring finger, but can occur on all the fingernails, and is apparently due to sympathetic overactivity. Inspect now for thyroid acropathy (acropathy is another term for clubbing), seen rarely in Graves’ disease but not with other causes of thyrotoxicosis.

Inspect for palmar erythema and feel the palms for warmth and sweatiness (sympathetic overactivity).

The eyes

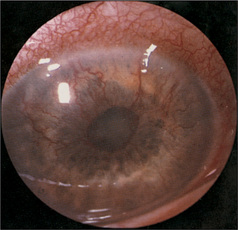

Examine the eyes for exophthalmos, which is protrusion of the eyeball from the orbit (Figure 10.7, Table 10.5). This may be very obvious, but if not, look carefully at the sclerae, which in exophthalmos are not covered by the lower eyelid. Next look from behind over the patient’s forehead for exophthalmos, where the eye will be visible anterior to the superior orbital margin. Now examine for the complications of proptosis, which include: (i) chemosis (oedema of the conjunctiva and injection of the sclera, particularly over the insertion of the lateral rectus); (ii) conjunctivitis; (iii) corneal ulceration (due to inability to close the eyelids); (iv) optic atrophy (rare and possibly due to optic nerve stretching); and (v) ophthalmoplegia (the inferior rectus muscle power tends to be lost first, and later convergence is weakened).

| Bilateral |

Next examine for the components of thyroid ophthalmopathy, which are related to sympathetic overactivity and are not specific for Graves’ disease. Look for the thyroid stare (a frightened expression) and lid retraction (Dalrymple’s signf), where there is sclera visible above the iris. Test for lid lag (von Graefe’s signg) by asking the patient to follow your finger as it descends at a moderate rate from the upper to the lower part of the visual field. Descent of the upper lid lags behind descent of the eyeball.

The neck

Examine for thyroid enlargement, which is usually detectable (60%–90% of patients). In Graves’ disease the gland is classically diffusely enlarged and is smooth and firm. An associated thrill is usually present but this finding is not specific for thyrotoxicosis caused by Graves’ disease. Absence of thyroid enlargement makes Graves’ disease unlikely, but does not exclude it. Possible thyroid abnormalities in patients who are thyrotoxic but do not have Graves’ disease include a toxic multinodular goitre, a solitary nodule (toxic adenoma), and painless, postpartum or subacute (de Quervain’sh) thyroiditis. In de Quervain’s thyroiditis there is typically a moderately enlarged firm and tender gland. Thyrotoxicosis may occur without any goitre, particularly in elderly patients. Alternatively, in hyperthyroidism due to a rare abnormality of trophoblastic tissue (a hydatidiform mole or choriocarcinoma of the testis or uterus), or excessive thyroid hormone replacement, the thyroid gland will not usually be palpable.

If a thyroidectomy scar is present, assess for hypoparathyroidism (Chvostek’si or Trousseau’sj signs; page 311). These signs are most often present in the first few days after operation.

The chest

Gynaecomastia (page 315) occurs occasionally. Examine the heart for systolic flow murmurs (due to increased cardiac output) and signs of congestive cardiac failure, which may be precipitated by thyrotoxicosis in older people.

The legs

Look first for pretibial myxoedema. This takes the form of bilateral firm, elevated dermal nodules and plaques, which can be pink, brown or skin-coloured. They are caused by mucopolysaccharide accumulation. Despite the name, this occurs only in Graves’ disease and not in hypothyroidism. Test now for proximal myopathy and hyperreflexia in the legs which is present in only about a quarter of cases.

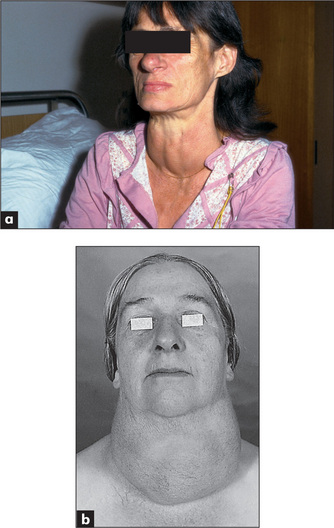

Hypothyroidism (myxoedema)

Hypothyroidism (deficiency of thyroid hormone) is due to primary disease of the thyroid or, less commonly, is secondary to pituitary or hypothalamic failure (Table 10.6). Myxoedema implies a more severe form of hypothyroidism. In myxoedema, for unknown reasons, hydrophilic mucopolysaccharides accumulate in the ground substance of tissues including the skin. This results in excessive interstitial fluid, which is relatively immobile, causing skin thickening and a doughy induration.

| Causes of thyrotoxicosis |

TSH = thyroid stimulating hormone. HCG = human chorionic gonadotrophin.

* Carl von Basedow (1799–1854), German general practitioner, described this in 1840 (Jod = iodine in German).

The symptoms of hypothyroidism are insidious but patients or their relatives may have noticed cold intolerance, muscle pains, oedema, constipation, a hoarse voice, dry skin, memory loss, depression or weight gain (Questions box 10.2).

Questions box 10.2

Examine the patient with suspected hypothyroidism as follows (see Good signs guide 10.3).

GOOD SIGNS GUIDE 10.3 Hypothyroidism

| Sign | Positive LR | Negative LR |

| Skin | ||

| Coarse | 5.6 | 0.7 |

| Cool and dry | 4.7 | 0.9 |

| Cold palms | NS | NS |

| Dry palms | NS | NS |

| Periorbital puffiness | 2.8 | 0.6 |

| Puffiness of wrists | 2.9 | 0.7 |

| Loss of eyebrow hair | 1.9 | NS |

| Speech | ||

| Hypothyroid speech | 5.4 | 0.7 |

| Thyroid gland | ||

| Goitre | 2.8 | 0.6 |

| Pulse | ||

| <70/min | 4.1 | 0.8 |

NS = not significant.

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007.

The arms

Test for proximal myopathy (rare) and a ‘hung-up’ biceps or Achilles tendon reflex (see below).

The face

Inspect the face (Figure 10.8). The skin, but not the sclerae, may appear yellow due to hypercarotenaemia. The skin may be generally thickened, and alopecia may be present, as may vitiligo (an associated autoimmune disease).

The thyroid gland

Many cases of hypothyroidism are not associated with an enlarged gland as there is little thyroid tissue. The exceptions include severe iodine deficiency, enzyme deficiency (inborn errors of metabolism), late Hashimoto’s disease or treated (with radioactive iodine) thyrotoxicosis (Table 10.6).

The legs

There may be non-pitting oedema. Ask the patient to kneel on a chair with the ankles exposed. Tap the Achilles tendon with a reflex hammer. There is apparently normal (in fact slightly slowed) contraction followed by delayed relaxation of the foot in hypothyroidism (the ‘hung-up’ reflex). Examine for signs of peripheral neuropathy and for other uncommon neurological abnormalities associated with hypothyroidism (Table 10.7).

| Common |

The pituitary

Panhypopituitarism (all pituitary hormones are deficient)

This is a deficiency of most or all of the pituitary hormones and is usually due to a space-occupying lesion or destruction of the pituitary gland (Table 10.8). Hormone production is often lost in the following order: (i) growth hormone (dwarfism in children, insulin sensitivity in adults); (ii) prolactin (failure of lactation after delivery); (iii) gonadotrophins (loss of secondary sexual characteristics, secondary amenorrhoea in women, loss of libido and infertility in men); (iv) TSH (hypothyroidism); and (v) ACTH (hypoadrenalism, with loss of secondary sexual hair due to decreased adrenal androgen production).

| Space-occupying lesion |

* Harold Sheehan (b. 1900), professor of pathology, Liverpool, England, described the syndrome in 1937.

Questions to ask the patient with suspected pan-hypopituitarism

General inspection

The patient may be of short stature (failure of growth hormone secretion before growth is complete). Look for pallor of the skin (due to anaemia or occasionally ACTH deficiency because of the loss of its melanocyte-stimulating activity), fine-wrinkled skin and lack of body hair (due to gonadotrophin deficiency). There may be complete absence of the secondary sexual characteristics (Table 10.9) if gonadotrophin failure occurred before puberty.

| This occurs at puberty in response to pituitary gonadotrophins | |

| Males | |

The face

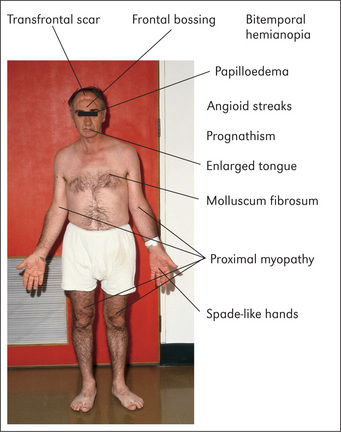

Look at the face more closely. Multiple skin wrinkles around the eyes are characteristic of gonadotrophin deficiency. Inspect the forehead carefully for hypophysectomy scars—transfrontal scars will be apparent (Figure 10.9) but not transsphenoidal ones, as this operation is performed through the base of the nose, via an incision under the upper lip.

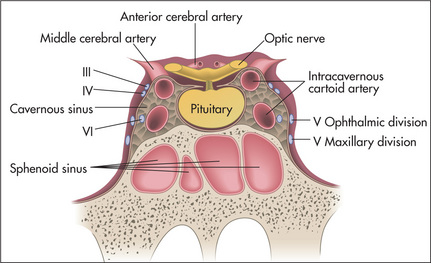

Examine the eyes (Chapter 13). The visual fields must be assessed for any defects, especially bitemporal hemianopia (an enlarging pituitary tumour may compress the optic chiasm), and the fundi examined for optic atrophy (optic nerve compression from a pituitary tumour). Assess the third, fourth, sixth and first divisions of the fifth cranial nerves, as these may be affected by extrapituitary tumour expansion into the cavernous sinus (Figure 10.10).

Feel the facial hair over the bearded area in men for normal beard growth (which is lost with gonadotrophin deficiency).

The ankle reflexes

Test for ‘hung-up’ jerks (Figure 10.11). These are an important sign of pituitary hypothyroidism. Occasionally, pituitary hypothyroid patients may be slightly overweight, but the classical myxoedematous appearance is usually absent.

Acromegalyk

This is excessive secretion of growth hormone, typically due to an eosinophilic pituitary adenoma.l Growth hormone stimulates the liver and other tissues to produce somatomedins which in turn promote growth. Growth hormone is also a protein anabolic hormone exerting its effects at the ribosomal level, and it is diabetogenic as it exerts an anti-insulin effect in muscle and increases hepatic glucose release. The disease has a very gradual onset and patients may not have noticed symptoms. Most patients, however, have headache caused by stretching of the dura by the enlarging pituitary tumour.

The arms

Proximal myopathy may be present (page 391). Palpate behind the medial epicondyle (the ‘funny bone’) for ulnar nerve thickening.

The face

Look in the mouth for an enlarged tongue that may not fit neatly between the teeth. The teeth themselves may be splayed and separated, with malocclusion as the jaw enlarges. The lower jaw may look square and firm (as it does on some American actors). When the jaw protrudes it is called prognathism (Greek pro ‘forwards’, gnathos ‘jaw’).

The lower limbs

Look for signs of osteoarthritis in the hips especially, and knees (page 269), and for pseudogout. Foot drop may be present because of common peroneal nerve entrapment (page 376).

The adrenals

Cushing’s syndrome

This is due to a chronic excess of glucocorticoids. Steroids have multiple effects on the body, due to stimulation of the DNA-dependent synthesis of select messenger ribonucleic acids (RNAs). This leads to the formation of enzymes, which alter cell function and result in increased protein catabolism and gluconeogenesis. Remember that Cushing’s disease is specifically pituitary ACTH overproduction, while Cushing’s syndrome is due to excessive steroid hormone production from any cause (Table 10.10; see Good signs guide 10.4, Questions box 10.4).

| Exogenous administration of excess steroids or ACTH (most common) |

| Adrenal hyperplasia |

ACTH = adrenocorticotrophic hormone.

GOOD SIGNS GUIDE 10.4 Cushing’s syndrome

| Sign | Positive LR | Negative LR |

| Vital signs | ||

| Hypertension | 2.3 | 0.8 |

| Body habitus | ||

| Moon face | 1.6 | 0.1 |

| Central obesity | 3.0 | 0.2 |

| General obesity | 0.1 | 2.5 |

| Skin findings | ||

| Thin skinfold (women) | 115.6 | 0.2 |

| Plethora | 2.7 | 0.3 |

| Hirsutism (women) | 1.7 | 0.7 |

| Ecchymoses | 4.5 | 0.5 |

| Red or purple striae | 1.9 | 0.7 |

| Acne | 2.2 | 0.6 |

| Extremities | ||

| Proximal muscle weakness | NS | 0.4 |

| Oedema | 1.8 | 0.7 |

NS = not significant.

From McGee S, Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2007

Questions box 10.4

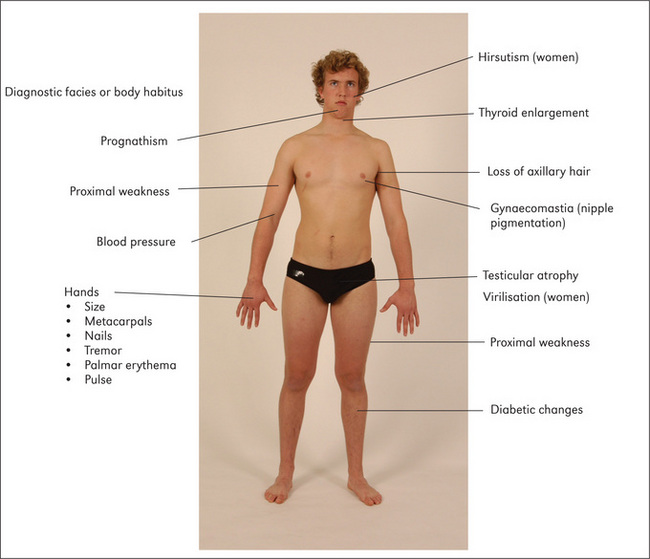

Standing

Have the patient undress to the underpants and, if possible, stand up (Figure 10.12). Look from the front, back and sides. Note moon-like facies and central obesity. The limbs appear thin despite sometimes very gross truncal (mostly intra-abdominal rather than subcutaneous fat) obesity.n This is the characteristic fat distribution that occurs with steroid excess. Bruising may be present (due to loss of perivascular supporting tissue–protein catabolism). Look for excessive pigmentation on the extensor surfaces (because of melanocyte-stimulating-hormone [MSH]-like activity in the ACTH molecule). Ask the patient to squat at this point to test for proximal myopathy, due to mobilisation of muscle tissue or excessive urinary potassium loss. Look at the back for the ‘buffalo hump’, which is due to fat deposition over the interscapular area. Palpate for bony tenderness of the vertebral bodies due to crush fractures from osteoporosis (a steroid anti-vitamin-D effect and increased urinary calcium excretion may be responsible in part for disruption of the bone matrix).

The abdomen

Lay the patient in bed on one pillow. Examine the abdomen for purple striae, which are due to weakening and disruption of collagen fibres in the dermis, leading to exposure of vascular subcutaneous tissues. In patients with Cushing’s syndrome these are wider (1 cm) than those seen in people who have gained weight rapidly for other reasons. They may also be present near the axillae on the upper arms or on the inside of the thighs. Palpate for adrenal masses (rarely a large adrenal carcinoma will be palpable over the renal area). Palpate for hepatomegaly due to fat deposition or rarely to adrenal carcinoma deposits.

The legs

Palpate for oedema (due to salt and water retention). Look for bruising and poor wound healing.

Synthesis of signs

Certain signs are of some aetiological value in Cushing’s syndrome.

Addison’s diseasep

This is adrenocortical hypofunction with reduction in the secretion of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids. It is most often due to autoimmune disease of the adrenal glands. Other causes are listed in Table 10.11.

| Chronic |

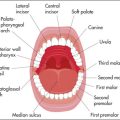

If this disease is suspected, look for cachexia. Then, with the patient undressed, look for pigmentation in the palmar creases (Figure 10.13), elbows, gums and buccal mucosa, genital areas and in scars. This occurs because of compensatory ACTH hypersecretion in primary hypoadrenalism (when there is adrenal disease), as ACTH has melanocyte-stimulating activity. Also inspect for vitiligo (localised hypomelanosis), an autoimmune disease that is commonly associated with autoimmune adrenal failure.

Take the blood pressure and test for postural hypotension. Remember that the rest of the autoimmune disease cluster may be associated with autoimmune adrenal failure (Table 10.12).

TABLE 10.12 A classification of conditions found in various combinations in autoimmune polyglandular syndromes

| Type I (rare autosomal recessive) | Type II (more common, HLA DRB1, DQA1, DQB1) |

Calcium metabolism

Primary hyperparathyroidism

This is due to excess parathyroid hormone (Table 10.13), which results in an increased serum calcium level, increased renal phosphate excretion and increased formation of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol by activation of adenyl cyclase in the bone and kidneys. Primary hyperparathyroidism causes problems with ‘stones’ (renal stones), ‘bones’ (osteopenia and pseudogout), ‘abdominal groans’ (constipation, peptic ulcer and pancreatitis) and ‘psychological moans’ (confusion) (Questions box 10.5).

| Primary |

Questions box 10.5

Other causes of hypercalcaemia are listed in Table 10.14.

TABLE 10.14 Important causes of hypercalcaemia

| Primary hyperparathyroidism |

| Carcinoma (from bone metastases or humoral mediators) |

| Thiazide diuretics |

| Vitamin D excess |

| Excessive production of vitamin D metabolites: e.g. sarcoidosis, certain T cell lymphomas |

| Thyrotoxicosis |

| Associated with renal failure (e.g. severe secondary hyperparathyroidism) |

| Multiple myeloma |

| Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia |

| Prolonged immobilisation or space flight |

Hypoparathyroidism

This results in hypocalcaemia with neuromuscular consequences (tetany) (Questions Box 10.6).

Questions box 10.6

It is usually a postoperative complication after thyroidectomy, but can be idiopathic. Hypocalcaemia can also result from end-organ resistance to parathyroid hormone (pseudohypoparathyroidism) (Table 10.15).

| Hypoparathyroidism: after thyroidectomy, idiopathic |

| Malabsorption |

| Deficiency of vitamin D |

| Chronic renal failure |

| Acute pancreatitis |

| Pseudohypoparathyroidism |

| Magnesium deficiency |

| Hypocalcaemia of malignant disease |

Next test for hyperreflexia, again due to neuromuscular irritability.

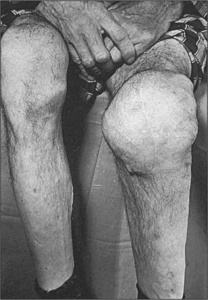

Pseudohypoparathyroidism

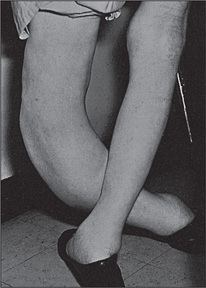

In this disease the patients have tetany (due to hypocalcaemia) as well as typical skeletal abnormalities. These include short stature, a round face, a short neck, thin stocky build and very characteristically short fourth or fifth fingers or toes (due to metacarpal or metatarsal shortening; this can be unilateral or bilateral) (Figure 10.14). Ask the patient to make a fist to demonstrate the characteristic clinical signs.

Syndromes associated with short stature

These conditions begin in childhood.

General inspection

First measure the height of the patient; in children this should be compared with percentile charts for age and sex. Look for the classical appearance of Turner’s syndrome, Down syndrome, achondroplasia or rickets (Figure 10.15), which may explain the short stature. The height of parents and siblings should be checked as well.

Note any evidence of weight loss, including loose skinfolds, which may suggest a nutritional cause (starvation, malabsorption or protein loss). Look for signs of hypopituitarism or hypothyroidism, or steroid excess. Sexual precocity (early onset of secondary sexual characteristics) causes relative tallness at first but short stature later.

Turner’s syndrome (45XO)

Sexual infantilism (failure of development of secondary sexual characteristics)—female genitalia.

Hirsutism

This is excessive hairiness in a woman beyond what is considered normal for her race (Table 10.16). It is caused by androgen (including testosterone) excess. In the examination of such a patient, it is important to decide whether virilisation is also present. Virilisation is the appearance of male secondary sexual characteristics (clitoromegaly, frontal hair recession, male body habitus and deepening of the voice) and indicates that excessive androgen is present.

| Polycystic ovary syndrome (commonest cause) |

| Idiopathic |

| Adrenal: androgen-secreting tumours e.g. Cushing’s syndrome, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, virilising tumour (more often a carcinoma than an adenoma) |

| Ovarian: androgen-secreting tumour |

| Drugs: phenytoin, diazoxide, streptomycin, minoxidil, anabolic steroids e.g. testosterone |

| Other: acromegaly, porphyria cutanea tarda |

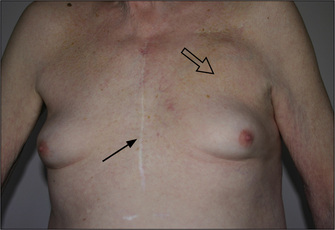

Gynaecomastia (Figure 10.16)

This is ‘true’ enlargement of the male breasts.5 Careful examination will detect up to 4 cm of palpable breast tissue in 30% of normal young men; this percentage increases with age. These men are unaware of any breast abnormality. Gynaecomastia occurs in up to 50% of adolescent boys, and also in elderly men in whom it is due to falling testosterone levels. Fat deposition (‘false’ enlargement) in obese men can be confused with gynaecomastia.

Examine the breasts (page 435) for evidence of localised disease (e.g. malignancy, which is rare), tenderness, which indicates rapid growth, and any discharge from the nipple. Detection of breast tissue in men is best performed with the patient sitting up. Squeeze the breast behind the patient’s nipple between the thumb and forefinger. Try to detect an edge between subcutaneous fat and true breast tissue.

Finally, examine the visual fields and fundi for evidence of a pituitary tumour.

Causes of pathological gynaecomastia are summarised in Table 10.17.

TABLE 10.17 Differential diagnosis (causes) of pathological gynaecomastia

| Increased oestrogen production |

Diabetes mellitusq

Diabetes mellitus is characterised by hyperglycaemia due to an absolute or relative deficiency of insulin. The causes of diabetes are listed in Table 10.18. The disease can present with asymptomatic glycosuria detected on routine physical examination or with symptoms of diabetes (Table 10.1), ranging from polyuria to coma as a result of diabetic ketoacidosis (Questions box 10.7).

| Criteria for diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: fasting plasma venous blood sugar level of 7.0 mmol/L or more (≥126 mg/dL), or a 2-hour postprandial blood sugar level of 11.1 mmol/L or more (≥200 mg/dL), on more than one occasion. |

| I. Type 1 |

Questions box 10.7

Questions to ask the diabetic patient

! denotes symptoms for the possible diagnosis of an urgent or dangerous problem.

General inspection (Figure 10.17)

The patient may be comatose due to dehydration, acidosis or plasma hyperosmolality. Kussmaul’s breathing (‘air hunger’) is present in diabetic ketoacidosis due to the acidosis (this occurs because fat metabolism is increased to compensate for the lack of availability of glucose; excess acetyl-coenzyme A is produced, which is converted in the liver to ketone bodies, and two of these are organic acids).

The lower limbs

Unlike most other systematic examinations, assessment of the diabetic can profitably begin with the legs, as many of the major physical signs are found to be here. In particular, vascular and neurological abnormalities in the feet must not be missed.6

Inspection

Note any leg ulcers, particularly on the toes or any area of the feet exposed to pressure (Figure 10.18). These ulcers are due to a combination of ischaemia and peripheral neuropathy (the cause of the neuropathy is unknown, but may be related to small vessel ischaemia and glycosylation of neural proteins).

Figure 10.18 Diabetic (neuropathic) ulcer

From McDonald FS, ed., Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine, with permission. © Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press.

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum is a reasonably specific skin manifestation of diabetes mellitus, but is rare (fewer than 1% of diabetics) (Figure 10.19). It is found over the shins, where a central yellow scarred area is surrounded by a red margin when the condition is active. These plaques may ulcerate.

Figure 10.19 Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum

From McDonald FS, ed., Mayo Clinic images in internal medicine, with permission. © Mayo Clinic Scientific Press and CRC Press.

Inspect the knees for the very rare Charcot’s joints (grossly deformed disorganised joints, due to loss of proprioception or pain, or both; this leads to recurrent and unnoticed injury to the joint) (Figure 10.20).

The face

The eyes

Test visual acuity. This may be permanently impaired because of retinal disease or temporarily disturbed because of changes in the shape of the lens associated with hyperglycaemia and water retention. Look for Argyll Robertson pupilsr, which are a rare complication of diabetes.

Using the ophthalmoscope, begin by examining for rubeosis (new blood vessel formation over the iris, which can cause glaucoma) (Figure 10.21). Then note any cataracts, which are related to sorbitol deposition in the lens (when glucose is present in high concentrations in the tissues it is converted to sorbitol by aldose reductase).

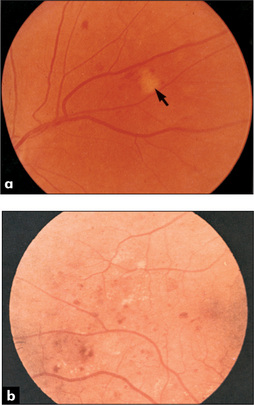

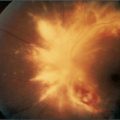

Non-proliferative changes (Figure 10.22) are directly related to ischaemia of blood vessels and include: (i) two types of haemorrhages—dot haemorrhages, which occur in the inner retinal layers, and blot haemorrhages, which are larger and which occur more superficially in the nerve fibre layer; (ii) microaneurysms, which are due to vessel wall damage; and (iii) two types of exudates—hard exudates, which have straight edges, and soft exudates (cottonwool spots), which have a fluffy appearance.

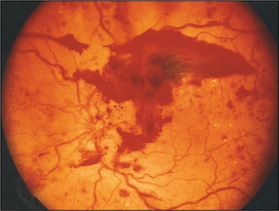

Proliferative changes (Figure 10.23) are changes in blood vessels in response to ischaemia of the retina. They are characterised by new vessel formation, which can lead to vitreal haemorrhage, scar formation and eventually retinal detachment. The detached retina appears as an opalescent sheet that balloons forward into the vitreous. The underlying choroid is visible through the detached retina as a bright red-coloured sheet. Look also for laser scars (small brown or yellow spots), which are secondary to photocoagulation of new vessels by laser therapy.

Paget’ss disease (osteitis deformans)

Head and face

Inspect the scalp for enlargement in the frontal and parietal areas and measure the head circumference (greater than 55 cm is usually abnormal). There may be prominent skull veins. Palpate for increased bony warmth and auscultate over the skull for systolic bruits. Both of these are due to increased vascularity of the skull vault. Oddly enough, bronchial breath sounds may be audible over the pagetic skull through the stethoscope. These are due to increased bone conduction of air. An area of very localised bony swelling and warmth may indicate development of a bony sarcoma (1% of cases of Paget’s disease may develop this complication).

The back

Inspect for kyphosis (due to vertebral involvement causing collapse of the vertebral bodies). Tap for localised tenderness, feel for warmth and auscultate for systolic bruits over the vertebral bodies.

1. Alvi A, Johnson JT. The neck mass. A challenging differential diagnosis. Postgrad Med. 1995;97:87-90. 93–94. Reviews how the history and examination narrow the differential diagnosis

2. Siminoski K. Does this patient have a goiter? JAMA. 1995;273:813-817. A guide to examining the thyroid

3. Wallace C, Siminoski K. The Pemberton sign. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:568-569. Describes the sign, due to a retrosternal goitre compressing cephalic venous inflow (and in some tracheal airflow)

4. McGee S. Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. St Louis: Saunders; 2007.

5. Braunstein GD. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:490-495. A good review

6. Edelson GW, Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Ciacco G. The acutely infected diabetic foot is not adequately evaluated in an inpatient setting. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2372-2378. All patients evaluated had undergone a less than adequate foot examination. Of admitted patients, 31% did not have their pedal pulses documented; 60% of the admitted patients were not evaluated for the presence or absence of protective sensation

Greenspan FS, Gardner DG, editors. Basic and clinical endocrinology, 8th edn, New York: Lange Medical/McGraw Hill, 2007.

Hegedus L. Clinical practice. The thyroid nodule. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1764-1771.

Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR. Williams textbook of endocrinology, 11th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

a Hakaru Hashimoto (1881–1934), Japanese surgeon.

b Harry Fitch Klinefelter (b. 1912), Baltimore physician, described the condition when he was a medical student.

c The first person to distinguish an enlarged thyroid from cervical lymphadenopathy was the Roman medical writer Aulus Aurelius Cornelius Celsus (53 BC–7 AD). He is more famous for describing the four cardinal signs of inflammation: redness, swelling, heat and tenderness.

d Robert Graves (1796–1853), Dublin physician.

e Henry Plummer (1874–1936), physician at the Mayo Clinic, USA.

f John Dalrymple (1803–52), British ophthalmic surgeon.

g Friedrich von Graefe (1828–70), professor of ophthalmology in Berlin, described this in 1864. He was one of the most famous ophthalmologists of the 19th century; Horner was one of his pupils. He died of tuberculosis at the age of 42.

h Fritz de Quervain (1868–1940), professor of surgery, Berne, Switzerland.

i Franz Chvostek (1835–84), Viennese physician.

j Armand Trousseau (1801–1867), Parisian physician.

k The acral parts are the hands and feet.

l Acromegaly was first described by Pierre Marie in 1886 and was first called hyperpituitarism by Harvey Cushing in 1909.

m From the Latin—habitus = the state or condition of a thing.

n The enthusiastic student can calculate the central obesity index. This is the sum of three truncal circumferences (neck, chest and waist) divided by six peripheral ones (arms, thighs and legs on both sides). A normal index is less than 1.

o Warren Nelson (1906–64), American endocrinologist.

p Thomas Addison (1793–1860) described the disease in 1849. Addison, Bright and Hodgkin made up the famous trio of physicians at Guy’s Hospital, London.

q This disease was called diabetes by ancient Greek and Roman physicians because the word diabetes means a siphon, referring to the large urine volume. Rather courageously, they distinguished diabetes mellitus from diabetes insipidus by the sweet taste of the urine: mellitus, ‘sweet’; insipidus, ‘tasteless’.

r Douglas Argyll Robertson (1837–1909), a Scottish ophthalmic surgeon and President of the Royal College of Surgeons, described these in 1869. The pupils are small, irregular and unequal, and react briskly to accommodation but not to light. Tertiary syphilis is another cause.

s Sir James Paget (1814–99), a surgeon at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, was also Queen Victoria’s doctor.