3 THE ELBOW

Applied Anatomy

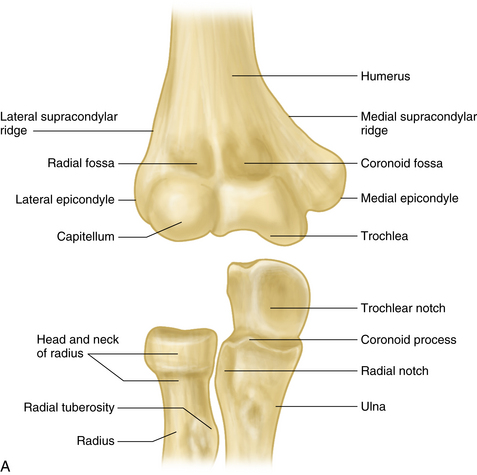

The elbow joint acts as both a hinge and a swivel, providing a stable link for lifting, pushing, or gripping and for positioning the hand in space. The hinge is formed by the humeroulnar (trochleoulnar) and humeroradial (capitelloradial) articulations at the cubital joint. The trochleoulnar is the principal joint, and the swivel is formed by the proximal radioulnar joint. These three joints share a common synovial cavity (Figure 3-1A).

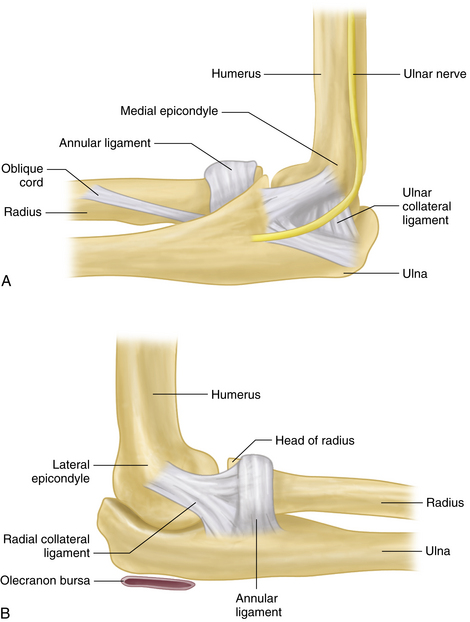

Stability of the elbow depends upon congruity of the articulating bones, anterior capsule, ligaments, and surrounding muscles. The ulnar and radial collateral ligaments provide medial and lateral stability to the joint. The cup-shaped annular ligament encircles the radial head and holds it in the radial notch of the proximal ulna (Figure 3-2A, B).

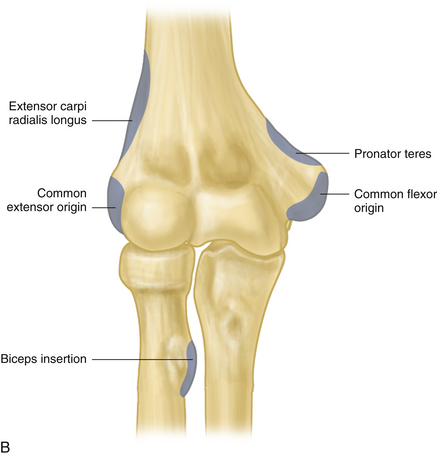

The common flexor tendon of the elbow (pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, flexor digitorum superficialis, and flexor carpi ulnaris) takes origin from the medial epicondyle and supracondylar ridge of the humerus. The common extensor tendon (extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis, brachioradialis, extensor digitorum communis, extensor carpi ulnaris, and anconeus) originates from the lateral epicondyle, supracondylar ridge, and distal humerus. The biceps tendon crosses the elbow joint to insert into the radial tuberosity (see Figure 3-1B).

The ulnar nerve runs in a bony groove behind the medial epicondyle (the cubital tunnel; Figure 3-2A). The olecranon bursa, a subcutaneous cushion at the olecranon process, is synovially lined but is anatomically separate from the elbow joint (see Figure 3-2B).

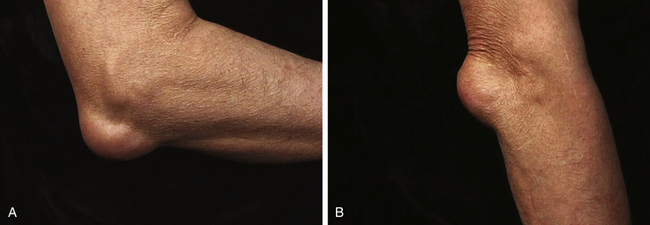

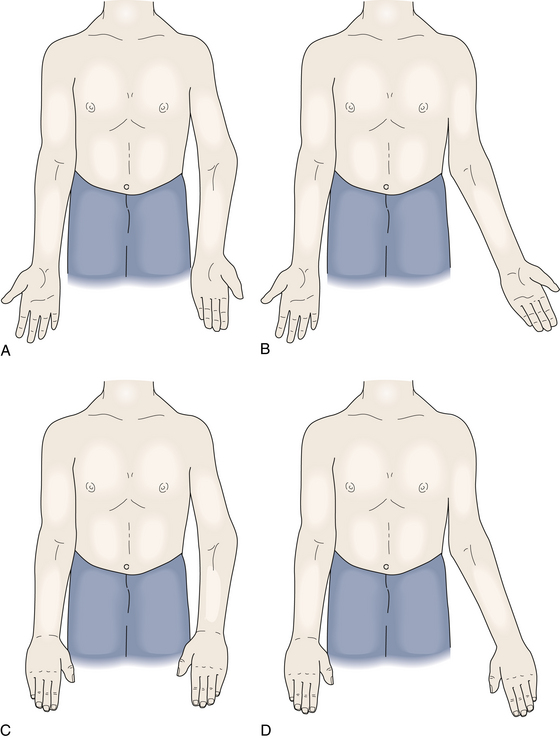

With the elbow in full extension, there is normally a slight valgus angulation of the forearm with respect to the humerus. This angulation, referred to as the carrying angle, is due to the oblique shape of the trochlea (see Figure 3-1A) and is normally ~5° to 10° in men and ~10° to 25° in women (Figure 3-3). This angle allows the forearms to clear the hips during the normal arm swing of ambulation and is important for carrying objects at the side, without requiring shoulder abduction. Excessive deviation of the forearm away from the body is referred to as cubitus valgus, and deviation of the forearm toward the body is called cubitus varus.

FIGURE 3-3 CARRYING ANGLE.

A, Right arm: normal; left arm: varus. B, Right arm: normal; left arm: valgus.

Pronation of the forearm and hand (palm of hand facing posteriorly in anatomic position) and supination (palm facing anteriorly in anatomic position) occur at the proximal and distal radioulnar joints, as the radial head pivots on the capitellum while the distal radius rotates around the distal ulna (see Figure 3-3). Normal pronation is ~75° and supination is ~85°. The pronator teres and pronator quadratus are the principal pronators, and the biceps and supinator muscles are the primary supinators of the radioulnar joints. A minimum total arc of pronation–supination of ~100° is required for normal activities.

History

Elbow pain is commonly caused by a relatively small number of conditions that include periarticular (tendinitis and bursitis), articular (arthritis), bone (fracture and dislocation), or neurologic problems (Table 3-1).

| Periarticular |

| Olecranon bursitis |

| Lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow) |

| Medial epicondylitis (golfer’s elbow) |

| Articular |

| Arthritis: crystalline (gout and pseudogout), rheumatoid, psoriatic; osteoarthritis (secondary); septic |

| Trauma: dislocation |

| Osseous |

| Trauma: fracture |

| Neurologic |

| Cubital tunnel syndrome (ulnar nerve) |

| Radiculopathy (referred pain due to cervical disk lesion) |

An initial screening history should readily identify those patients with elbow pain secondary to fracture or dislocation, and an appropriate radiographic and orthopedic assessment can be initiated. A history of unusually intense or repetitive recreational or occupational activity is important, particularly in patients with suspected tendinitis. Furthermore, pain characteristics may suggest neurologic involvement (burning, tingling, and radiation), and associated symptoms in the neck and shoulder or wrist and hand may suggest pain referral from a site other than the elbow. Additional articular symptoms in other sites may suggest a more generalized process, such as rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis.

Physical Examination

INSPECTION

With the elbows in full extension, observe the carrying angle, noting any valgus or varus angulation. Inspect the elbow for erythema (acute inflammation or infection) or any vesicular rash, such as Herpes zoster. Check the extensor surface of the elbow for any subcutaneous nodules (rheumatoid nodules or gouty tophi) or cutaneous psoriasis (psoriatic arthritis). Inspect the olecranon for any visible swelling (olecranon bursitis; Table 3-2).

| Basic Exam |

| INSPECTION |

| ____ Note carrying angle |

| ____ Inspect elbow (rashes, abrasions, or skin breaks) |

| PALPATION |

| ____ Palpate olecranon surface (subcutaneous nodules, tophi) |

| ____ Palpate olecranon bursa (bursal swelling; nodules, tophi) |

| ____ Palpate lateral joint line (synovial swelling) |

| RANGE OF MOTION |

| ____ Assess elbow flexion |

| ____ Assess elbow extension |

| ____ Check forearm pronation and supination |

| SPECIAL TESTING: LATERAL EPICONDYLITIS |

| ____ Palpate lateral epicondyle and ~1 cm distally |

| ____ Test resisted wrist extension |

| SPECIAL TESTING: MEDIAL EPICONDYLITIS |

| ____ Palpate medial epicondyle and ~1 cm distally |

| ____ Test resisted wrist flexion and forearm pronation |

| SPECIAL TESTING: ULNAR NEUROPATHY |

| ____ Palpate nerve in ulnar groove |

| ____ Check Tinel sign |

| ____ Palpate for snapping ulnar nerve |

| ____ Test forced elbow flexion (~60 seconds) |

| ____ Inspect interosseous muscles and assess strength of fifth finger to resisted abduction |

| ____ Check sensation in fourth and fifth fingers |

| SPECIAL TESTING: LIGAMENTOUS LAXITY |

| ____ Stress medial and lateral collateral ligaments |

PALPATION

Slide your other hand along the forearm to the olecranon surface. Note any palpable subcutaneous nodules or swelling of the olecranon bursa. Swelling of the olecranon bursa presents itself as visible and/or palpable distension directly overlying the olecranon, often looking like the comic character Popeye (Figure 3-4).

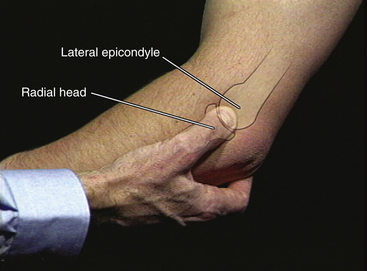

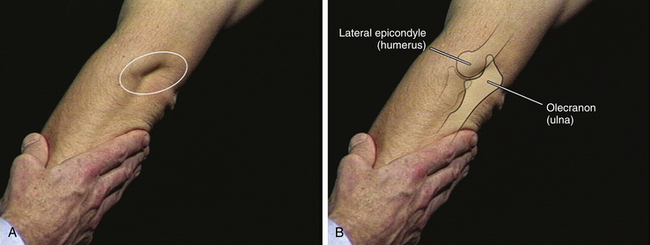

Next, identify the small depression normally present between the olecranon and the lateral epicondyle, which is especially visible during full extension (Figure 3-5). This depression is the first area to be obliterated by an elbow effusion. Now, use your examining thumb to identify and palpate the lateral epicondyle. Slide your thumb slightly distally while you gently pronate and supinate the forearm with your other hand still in the “handshake” position. You can now feel the patient’s radial head, moving under your palpating thumb. The joint space between the lateral epicondyle and radial head should now be readily appreciable with only skin and subcutaneous tissue between your thumb and the joint line itself. Next, continue palpating the joint line while you bring the elbow into full extension. Note whether there is any pain or resistance to full extension, frequently seen with elbow joint synovitis (Figure 3-6).

FIGURE 3-5 INSPECTION OF THE LATERAL JOINT LINE.

A, Normal sulcus visible in extension. B, Bony anatomy present beneath the sulcus.

Swelling of the elbow joint results in progressive obliteration of the normal small lateral sulcus and a “boggy” or thickened feel to the usually well-defined depression (joint line) between the lateral epicondyle and radial head. Furthermore, synovial distension may produce a visible or palpable bulge when the elbow is moved into full extension, as intraarticular pressure increases.

RANGE OF MOTION

Next, flex and extend each elbow. Full elbow flexion places the proximal forearm against the distal biceps (~150° to 160°). Elbow extension returns the joint to the outstretched anatomical position (0°). Place your hand under the olecranon to assist you in detecting any deficit in full extension (flexion contracture). Return the elbow to 90° of flexion and assess forearm pronation and supination.

SPECIAL TESTING

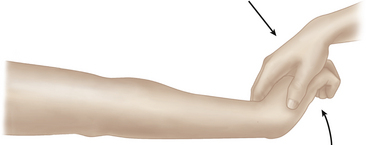

Next, if appropriate, assess for the presence of lateral epicondylitis (“tennis elbow”). Bring the elbow into partial flexion and identify the lateral epicondyle with your thumb. Palpate the lateral epicondyle and apply progressively increasing pressure to the epicondyle itself. Then, move ~1 cm distally and again apply pressure. Note any focal tenderness. Next, place the elbow in full extension and support the forearm with your arm. Ask the patient to make a fist and “cock it back” (fingers flexed and wrist extended). Supply downward force against the dorsum of the hand against the patient’s resistance. Note any lateral elbow pain (Figure 3-7).

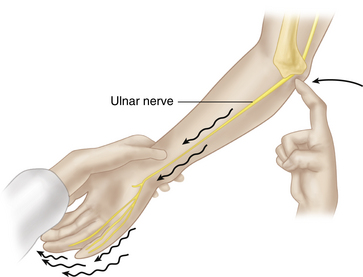

If indicated, assess for ulnar nerve irritation or compression in the cubital tunnel. Palpate the ulnar nerve at the medial aspect of the elbow, in the ulnar groove. Tap lightly over the ulnar nerve (Tinel sign, Figure 3-8) and note any pain or tingling radiating to the forearm and lateral hand (fourth and fifth digits). Next, palpate the ulnar groove during elbow flexion and extension. Note whether the nerve slips in and out of the ulnar groove. Finally, move the elbow into full flexion for ~60 seconds. Note any tingling or numbness in the ulnar aspect of the hand. Complete your assessment by checking for interosseous wasting and abduction strength of the fifth finger. Check sensory function over the fourth and fifth fingers. Note any deficits.

Common Disorders of the Elbow

OLECRANON BURSITIS

The olecranon bursa is one of the few bursae where irritation and inflammation present as clinically visible and palpable swelling (Figure 3-4). Acute trauma may lead to hemorrhagic swelling within the bursa. Repetitive pressure on the olecranon may cause chronic swelling. The two most common inflammatory conditions affecting the olecranon bursa are rheumatoid arthritis and gout. The bursa may swell suddenly and painfully in acute gout; may swell gradually with minimal pain, warmth, or erythema in rheumatoid arthritis; or may swell imperceptibly over time with the development of rheumatoid nodules or gouty, tophaceous deposits.

ELBOW JOINT SWELLING

Elbow joint swelling is usually experienced by the patient as a deep, poorly localized ache aggravated by motion, especially at the extremes of flexion and extension. The greater the acuteness of inflammation, the more likely the patient is to hold the elbow at ~70° of flexion, the position of lowest intraarticular pressure. Chronic elbow synovitis, as in rheumatoid arthritis, may be minimally tender or not tender at all, with no accompanying warmth or visible erythema; acute inflammatory synovitis, as in acute crystalline arthritis, may exhibit all the cardinal features of inflammation. If the elbow joint is the site of an acute inflammatory monoarthritis, it is imperative, as with all acute monoarthritides, to aspirate the joint to check for crystals or infection.

Aspiration and Injection of the Elbow

OLECRANON BURSA

Using a retracted ballpoint pen, mark the skin on the ulnar surface ~1 cm distal to the olecranon bursa. Prep the skin with iodine solution and allow to air dry, then prep with alcohol. Using a 22 gauge needle, inject 1% or 2% lidocaine subcutaneously at the site of your skin mark and advance proximally into the bursa. Use an 18 gauge needle on a 10 mL syringe for aspiration. While you advance the needle with your dominant hand, use your nondominant hand to squeeze the bursa between your gloved thumb and index fingers to help guide the needle into the bursa. Occasionally, the bursal fluid is loculated, and you will need to make a series of passes with the needle to aspirate fluid (your nondominant hand is invaluable here in helping stabilize and center the bursa). Aspirate the bursal fluid. If clinically appropriate, inject corticosteroid (Figure 3-9). This subcutaneous “tunnel” technique avoids puncturing the bursa on its exposed extensor surface and decreases the likelihood of fluid leakage with elbow flexion subsequent to aspiration.

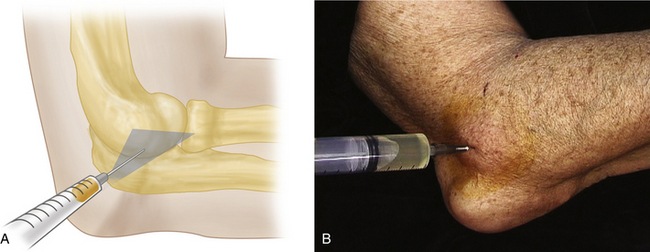

Elbow Joint

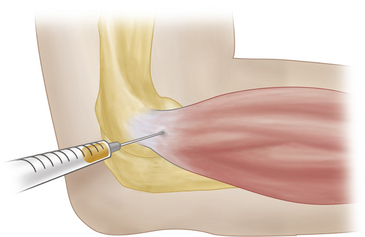

With the elbow in ~45° of flexion, identify the lateral epicondyle, the radial head, and the tip of the olecranon. These three points form a triangle, the center of which is the entry point for the lateral approach to the elbow joint. Palpate at the center of this imaginary triangle, and use a retracted ballpoint pen to make a mark at this site. Prep the skin with iodine and allow to air dry, then prep with alcohol. Use a 22 gauge needle and 1% or 2% lidocaine to create a skin wheel. Now, direct the needle along a plane parallel to an imaginary line connecting the lateral and medial epicondyles. (Using this angle of needle entry, rather than perpendicular to the skin surface, may make successful aspiration much easier; Figure 3-10A). As you advance the needle, inject lidocaine until you enter the joint space. Once in the joint space, change syringes and aspirate with a 10 mL syringe. Occasionally, the synovial fluid is loculated and may be difficult to aspirate initially. You may need to rotate the needle or make several small changes in needle depth to obtain fluid (gentle, rather than forceful, suction is often the most effective). Aspirate the joint completely if possible. If clinically appropriate, inject corticosteroid.

Lateral Epicondyle

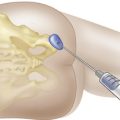

Using a retracted ballpoint pen, mark the skin at the point of maximum tenderness, usually ~1 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle (Figure 3-11). Prep the skin with iodine and allow to air-dry, then prep with alcohol. Using a 25 gauge needle, inject 1% or 2% lidocaine into the skin. Advance into and through the extensor tendon and inject additional lidocaine. Leave the needle in place, exchange syringes, and inject a corticosteroid preparation. After completing the procedure, it is useful to repeat resisted elbow extension. If the injection has been appropriately placed, there should be a dramatic decrease in pain with this provocative maneuver, frequently surprising the patient.

Allander E. Prevalence, Incidence and Remission Rates of Common Rheumatic Diseases and Syndromes. Scand. J. Rheumatol.. 1974;3:145-153.

Binder A.I., Hazleman B.L. Lateral Humeral Epicondylitis: A Study of Natural History and the Effect of Conservative Therapy. Br. J. Rheumatol.. 1983;22:73-76.

Buehler M.J., Thayer D.T. The Elbow Flexion Test: A Clinical Test for the Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. Clin. Orthop. 1988;233:213-216.

Canoso J.J., Barza M. Soft Tissue Infections. Clin. Rheum. Dis. 1993;19:293-309.

Kraushaar B.S., Nirschl R.P. Tendinosis of the Elbow (tennis elbow). J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1999;81:259-278.

Magee D.J. Orthopedic Physical Assessment, fourth ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2002.

Regan W.D., Morrey B.F. The Physical Examination of the Elbow. In: Morrey B.F., editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1993.

Yocum L.A. The Diagnosis and Non-operative Treatment of Elbow Problems in the Athlete. Clin. Sports Med. 1989;8:439-451.