Chapter 6 The Elbow

The elbow is a strong hinge joint that allows flexion and rotation of the forearm. It also provides the bony origin for most of the extrinsic muscles of the wrist and hand. It is frequently affected by inflammatory and traumatic conditions that seriously alter its function. Osteoarthritis is rare, however.

Anatomy

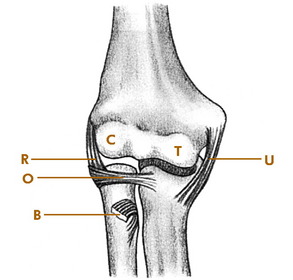

The elbow joint is formed by the articulation between the humerus and the radius and ulna (Fig. 6-1). The humerus widens distally to form the lateral and medial condyles. The capitellum of the lateral condyle articulates with the radial head, and the trochlea articulates with the ulna. The head of the radius also articulates with the lateral aspect of the ulna and is held in position by the orbicular ligament. Medial and lateral collateral ligaments provide additional stability.

Examination

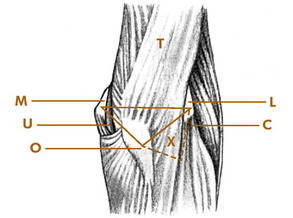

The tip of the olecranon process and the epicondyles form useful bony landmarks (Fig. 6-2). When the elbow is fully extended and viewed from behind, these points form a straight, transverse line. With the elbow flexed, they form an isosceles triangle. Just distal to the lateral epicondyle lies the radial head. These two points, along with the olecranon process, form another triangle on the posterolateral aspect of the joint. This triangle is occupied by the anconeus muscle. This area usually bulges when the joint is distended by fluid and is an excellent site for joint aspiration.

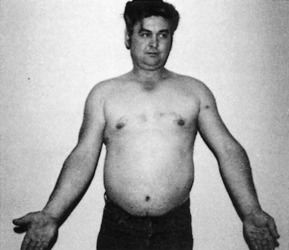

With the forearm in the supinated position, an angle is formed with the arm at the elbow joint. This is referred to as the “carrying angle” and normally measures 15 to 20 degrees. Alterations in this angle may occur following injury or infection, especially in the young, and may lead to excessive cubitus valgus or even varus (Fig. 6-3).

Roentgenographic Anatomy

The roentgenographic features of the elbow are well visualized by standard anteroposterior and 90-degree flexion lateral views (Fig. 6-4). Comparison views of the opposite elbow should be obtained whenever necessary. Oblique views are helpful when the diagnosis is uncertain.

Epicondylitis

Epicondylitis is one of a large group of musculoskeletal disorders commonly termed “overuse syndromes.” Although it is often called an inflammatory condition, degeneration (tendinosis) is usually present instead, often with the development of local neovascular tissue. The condition is characterized by pain at the origin of the flexor muscles at the medial epicondyle or the extensor muscles at the lateral epicondyle. Some cases may start with a direct blow, but the cause is usually unknown. Minor tears in the tendinous attachments of these muscles are often present. The disorder is common in individuals whose activities require repeated use of the extensor or flexor mechanism of the forearm. The lateral side (“tennis elbow”) is more commonly involved. In tennis players, the backhand swing seems to be the main offender. Involvement of the medial epicondyle is often called “golfer’s elbow.”

CLINICAL FEATURES

The onset is usually gradual. A dull ache that worsens with use of the involved muscles appears over the affected epicondyle. Palm-down lifting is painful. Activities that require rotation and grasping, such as opening a jar, increase the pain. The pain often radiates into the forearm. Extension or flexion of the hand against resistance reproduces the pain at the affected epicondyle (Fig. 6-5). The point of maximum tenderness can usually be well localized by digital pressure applied about 1 cm distal to the epicondyle. The roentgenograms are usually normal, although a traction spur or calcification may be present.

TREATMENT

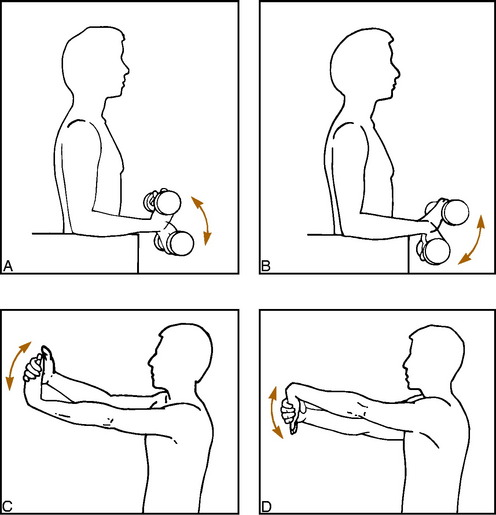

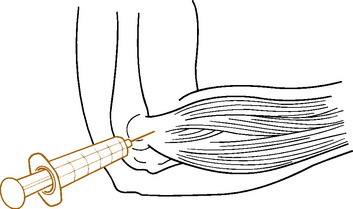

Treatment is similar to that for other “musculotendinous overuse syndromes.” Rest is important, and this can frequently be obtained merely by avoiding the offending activity. Applying ice after exercise can help. A careful exercise program of gentle stretching and strengthening is begun as pain subsides (Fig. 6-6). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are given as necessary. Local infiltration of the affected area with 1 to 2 mL of a steroid/lidocaine mixture often provides permanent or at least long-lasting relief (Fig 6-7). The injection is placed in the area of maximum local tenderness, usually about 1 cm distal to the bony epicondyle, and may be repeated two or three times. A tennis elbow counterforce strap may also be tried. It theoretically works by dampening the force transmitted to the elbow from the hand and wrist (see Chapter 15). Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) has even been tried in epicondylitis, but the results are inconclusive. The disease is usually self-limited, but symptoms may persist for several months before full recovery. Conservative treatment is effective in most cases. Often, spontaneous rupture of the aponeurosis probably occurs, which cures the pain, usually without any significant residual weakness. Surgery is reserved for cases that do not respond to medical management. Eventually, the recreational tennis player may simply have to decide to withdraw from the sport.

Osteochondritis Dissecans

Osteochondritis dissecans is a condition in which a portion of subchondral bone undergoes avascular necrosis. This segment of bone, with its overlying articular cartilage, may partially or completely separate from the adjacent bone and even extrude into the joint to form a loose body. The disorder is most commonly seen in the knee joint, but a similar condition also occurs in the elbow, ankle, and hip joints. The cause is unknown, but it is probably traumatic in origin. Repetitive compression of the lateral elbow joint may be responsible. The condition is sometimes a cause of “Little League elbow.”

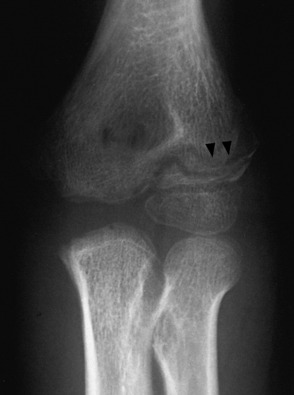

CLINICAL FEATURES

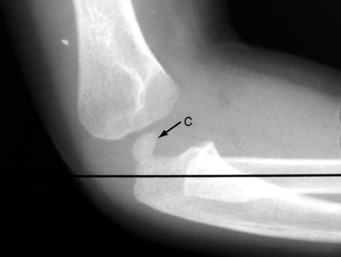

In the elbow, the disorder is most common during adolescence, and males are usually affected. The onset of symptoms is gradual, and a history of trauma may be elicited. The patient frequently complains of a dull, aching pain that is often associated with stiffness. Occasionally, episodes of locking occur if the fragment has become extruded into the joint. The physical findings consist of limitation of motion, local tenderness, and joint effusion. Roentgenographically, the capitellum is the most common site of involvement (Fig. 6-8).

Pronator Syndrome

The median nerve gives off its motor branch, the anterior interosseous nerve, below the elbow as it passes between the two heads of the pronator teres muscle just behind the biceps aponeurosis. An uncommon form of compression neuropathy can occur at this site, which is called pronator syndrome. Entrapment can also cause a very specific clinical presentation, sometimes referred to as the anterior interosseous nerve syndrome if only the motor branch is affected. The etiology is usually some form of localized anatomic compression, but the disorder can follow injury or even a traumatic phlebotomy.

If only the anterior interosseous branch is affected, sensation to the hand is normal. Forearm pain and weakness may develop, and if sufficient compression has occurred, weakness of the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) to the index finger may be present. The patient may then be unable to form a circle when trying to pinch the index and thumb because of inability to flex the distal phalanges of those fingers (Fig. 6-9).

Pulled Elbow

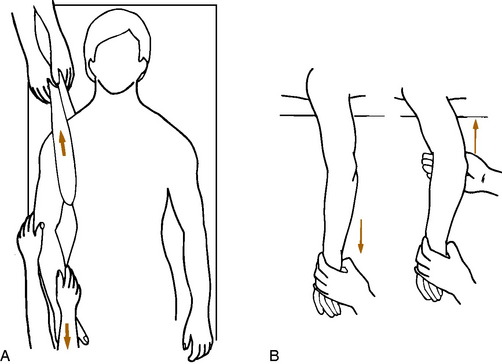

Pulled elbow, or “nursemaid’s elbow,” is a disorder in which the head of the radius becomes subluxed beneath the orbicular ligament (Fig. 6-10). This occurs as a result of longitudinal traction on the hand with the elbow extended and the forearm in a pronated position. A common situation in which this occurs is when a child is lifted up by the wrist or hand.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Pulled elbow is most common between the ages of 1 and 3 years and is rare after the age of 6. Clinically, an audible snap may be heard when the radial head subluxes. The arm is then held motionless at the side in slight flexion and pronation. The radial head is tender. Roentgenographic findings are usually normal, presumably because the subluxation has spontaneously reduced or because reduction occurred in the process of radiographic positioning. Rarely, an abnormality may be visualized (Fig. 6-11).

TREATMENT

Reduction is easily accomplished by supinating and flexing the forearm while applying manual pressure over the radial head (Fig. 6-12). A palpable click can be noted as reduction occurs, and the pain is immediately relieved. Reduction sometimes occurs in the radiology department when the technician places the forearm and the elbow in the flexed and supinated position to obtain a lateral view of the elbow. After reduction, a sling is worn for 5 to 7 days, if needed. Recurrences occasionally take place and are treated in a similar manner.

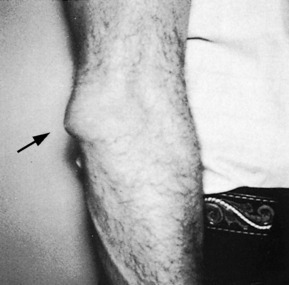

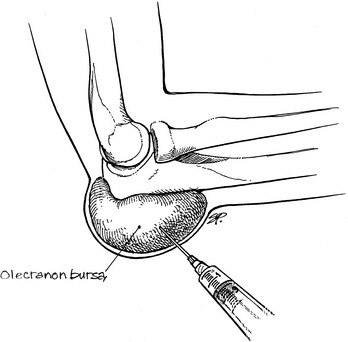

Olecranon Bursitis

With repetitive trauma, a chronic inflammatory reaction may occur that results in the formation of a thickened, rubbery bursa (Fig. 6-13). This bursa is usually not painful, in contrast to the swelling that occurs after an acute injury. Palpation may reveal multiple, small, hard nodules that feel like loose bodies. These usually are not chips of bone but instead represent villous thickenings or tissue debris in the bursa. Aspiration of the bursa may be attempted, but the fluid often recurs. Resolution may be improved by intrabursal injection of 1 mL of steroid (Fig. 6-14). Incision is not recommended because a chronic draining sinus infection often results. If the bursa is chronically painful, excision is recommended. Usually, the bursa will “dry up” eventually on its own, however. Elbow pads or other forms of protection may be helpful.

Dislocation of the Elbow

Dislocation of the elbow is a common injury and is usually posterior in direction (Fig. 6-15). It is generally the result of a fall on the outstretched hand with the elbow extended. Examination will reveal obvious deformity that must be differentiated from a supracondylar fracture. Avulsion fractures of the medial epicondyle and fractures of the radial head occasionally occur at the same time that may require surgical intervention. Reduction is performed as soon as possible. It can usually be accomplished by gentle, steady traction on the wrist with countertraction on the shoulder (Fig. 6-16). A general anesthetic is usually unnecessary. Extension of the elbow to unlock the olecranon may be necessary. After reduction, the elbow is tested for stability, and postreduction roentgenograms are always obtained. Lack of full motion following reduction suggests the possibility of an intraarticular fracture fragment. If the elbow is stable after reduction, it is rested in a sling for a few days. Gentle range-of-motion exercises are instituted as early as possible. Temporary stiffness is common, and full recovery of elbow motion may take several weeks. Motion should never be forced. The patient should be allowed to progress as tolerated. Forced passive motion only encourages more swelling, which leads to more stiffness. Some residual restriction of motion is not uncommon, but it is usually of such a minor degree that it does not interfere with function.

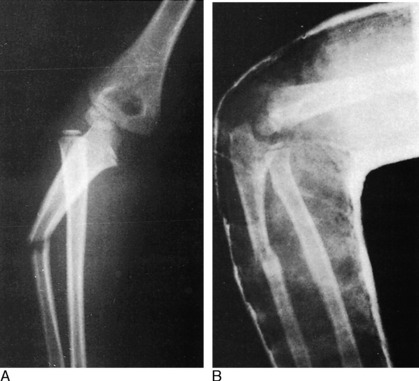

Dislocation of the Radial Head in Children

This is a disorder that is usually traumatic but may occasionally be congenital or developmental in nature. Most traumatic cases dislocate anteriorly (Fig. 6-17). The mechanism of injury is usually a fall on the outstretched pronated arm, and the injury is frequently missed. Some cases may be associated with a “bent” ulna, suggesting a Monteggia type of injury. Congenital dislocations are usually posterior and are frequently bilateral. They may be associated with other congenital anomalies such as Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. Developmental dislocations are usually the result of cerebral palsy or neurologic injury and are commonly posterolateral. These two types of radial head dislocations usually have no pain and little functional impairment. No treatment is required unless symptoms are present.

Fractures of the Elbow Region

FRACTURES OF THE HEAD AND NECK OF THE RADIUS

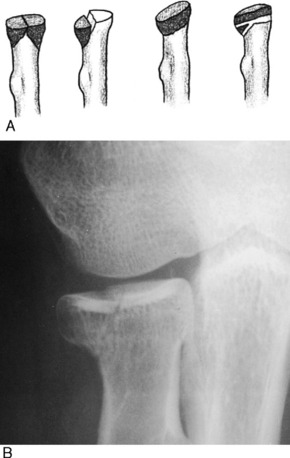

Fractures of the radial head and neck result from a fall on the outstretched hand with the elbow extended (Fig. 6-18). All are characterized by tenderness over the radial head, local swelling, and pain on rotation or flexion of the forearm.

Fig. 6-18 A, Various types of fractures of the radial head or neck that may be treated nonsurgically. B, Typical head fracture in which full, pain-free motion was restored following conservative treatment.

Significantly comminuted fractures in adults are usually treated by early excision of the entire radial head. Otherwise, permanent restriction of joint motion and traumatic arthritis may result. Early removal is especially indicated in grossly comminuted and displaced fractures because the fracture fragments may act as a nidus for soft tissue calcification in the anterior elbow region, and myositis ossificans may result (Fig. 6-19). Open reduction may be considered in fractures with a single large displaced fragment.

FRACTURES OF THE OLECRANON

Fractures of the olecranon usually result from falls on the tip of the elbow (Fig. 6-20). They are either displaced or undisplaced. The extensor mechanism is intact in undisplaced fractures, and further displacement is unlikely. These fractures are easily treated with a posterior splint for 2 weeks, followed by a sling and gradually increasing range-of-motion exercises.

THE SUPRACONDYLAR FRACTURE

This is the most common elbow fracture in children. The distal fragment is usually displaced posteriorly (Fig. 6-21). Neurologic and vascular injuries are not uncommon, but they usually only when the fracture is severely displaced.

Undisplaced or minimally angulated fractures are treated with a posterior splint for 4 to 6 weeks.

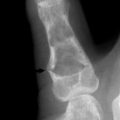

FRACTURE OF THE LATERAL HUMERAL CONDYLE

This is a common fracture in children and is usually a Salter–Harris type IV injury. The fracture is sometimes missed because only a thin line of metaphyseal fragment may be visible, with the remainder of the fracture line crossing the cartilaginous trochlea (Fig. 6-22). It is a potentially serious injury because the fracture line passes through the growth plate and into the joint. Nonunion, malunion, and traumatic arthritis are potential complications.

Displaced fractures usually need open reduction with pinning.

Adams JE. Bone injuries in very young athletes. Clin Orthop. 1968;58:129-140.

Blount WP. Fractures in children. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1955.

Boyd HB, McLeod ACJr. Tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1183-1187.

Ciccotti MG, Charlton WP. Epicondylitis in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20:77-93.

Garden RS. Tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43:100.

Hak DJ, Golladay GJ. Olecranon fractures: treatment options. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:266-275.

March HC. Osteochondritis of the capitellum (Panner’s disease). AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1944;51:682. B

Nirschl RP, Ashman ES. Tennis elbow tendinosis (epicondylitis). Instr Course Lect. 2004;53:587-598.

Tullos HS, King JW. Lesions of the pitching arm in adolescents. JAMA. 1972;220:264-271.