CHAPTER 19 The Effect of Substance Use Disorders on Children and Adolescents

Health professionals, including primary care pediatricians and developmental-behavioral pediatricians, encounter large numbers of children, adolescents, pregnant women, and other family members or adult caretakers who have or are affected by alcohol and other drug-related problems. Developmental-behavioral pediatricians and other health professionals are in an ideal position to identify substance use disorders and related problems in the children, adolescents, and families whom they care for and should be able to provide preventive guidance, education, and intervention. Although it is easiest to identify substance use disorders and related problems in children, adolescents, and families who are most severely affected, the bigger challenge is to identify affected individuals early in their involvement and to intervene quickly and effectively. The magnitude of the problem, the nature and effect of substance use disorders on individuals and families, and the role of the health care professional in the prevention, intervention, and treatment of substance use disorders must be appreciated.

INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE

According to data from the 2004 National Survey of Drug Use and Health,1 formerly called the National Household Survey, 121 million and 70.3 million U.S. citizens, aged 12 and older, are estimated to be current users of alcohol and tobacco, respectively. In 2004, about 10.8 million underage persons aged 12 to 20 (28.7%) reported drinking alcohol in the previous month. Past-month alcohol use rates ranged from 16.4% among Asians to 19.1% among black persons, 24.3% among Native Americans or Alaska Natives, 26.6% among Hispanic persons, and 32.6% among white persons. Nearly 7.4 million (19.6%) individuals in the age group were binge drinkers, and 2.4 million (6.3%) were heavy drinkers. Among persons aged 12 to 20, binge drinking was reported by 22.8% of white persons, 19.0% of Native Americans or Alaska Natives, 19.3% of Hispanic persons, and 18.0% of persons reporting belonging to two or more races. However, binge drinking was reported by only 9.9% of black persons and 8.0% of Asians. Among youths aged 12 to 17 in 2004, an estimated 3.6 million (14.4%) had used a tobacco product in the previous month, and 3.0 million (11.9%) had used cigarettes. Current cigarette use increased with age up to the mid-20s and then declined. An estimated 2.8% of 12- or 13-year-olds, 10.9% of 14- or 15-year-olds, and 22.2% of 16- or 17-year-olds were current cigarette smokers in 2004.

Another 19.1 million United States citizens (7.9% of the population) aged 12 years or older currently use illicit drugs.1 Among all youths aged 12 to 17 in 2004, 10.6% were current users of illicit drugs: 7.6% used marijuana, 3.6% used prescription-type drugs for nonmedical reasons, 1.2% used inhalants, 0.8% used hallucinogens, and 0.5% used cocaine.

The highest rate of illicit drug use, 19.4%, was reported among young adults aged 18 to 25 years. It is estimated that 22.5 million U.S. citizens met criteria for alcohol or drug dependence. The percentages of dependence were highest among Native Americans and persons of multiracial heritage: 20.2% and 12.2%, respectively. White and African American individuals had similar rates of dependence: 9.6% and 8.3%, respectively. Asian Americans had the lowest rates of dependence, 4.7%, whereas the rate for Hispanic Americans was 9.8%.2

Among pregnant women aged 15 to 44 years, 3.3%, representing slightly more than 130,000 births per year, reported using illicit drugs the month before interview; this rate was significantly lower than the rate among women who were not pregnant (10.3%).1,3 Rates of drug use during pregnancy were highest among Native Americans/Alaska Natives (10.1%) and persons reporting a heritage of two or more races (11.4%). In 2002, marijuana was the most widely used illicit drug among pregnant women (2.9%).3 Of all pregnant women in the United States, 1% used illicit drugs other than marijuana, including cocaine (or crack), heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, or any prescription-type psychotherapeutic for nonmedical use of. Alcohol and tobacco remain significant preventable threats to favorable birth and neurodevelopmental outcomes. Among pregnant women, aged 15 to 25 years, 5% reported alcohol binge drinking (five or more drinks at the same time or within a couple of hours of each other) on at least one day within the month before the survey. Seventeen percent of pregnant women smoked cigarettes within the month before the survey.1

TOBACCO

Tobacco kills more individuals in the United States each year than do all other substances and firearms combined.4 The average smoker starts smoking at age 12 years. Adolescent smokers are more likely to become nicotine dependent through smoking fewer cigarettes a day than are adult smokers.5 Worldwide, the Global Youth Tobacco Survey6 reports that 24% of youth surveyed began smoking before age 10, and younger women aged 13-15 years are as likely to use tobacco products as are young men. Adolescents see the positive aspects of smoking as helping with boredom, dealing with stress, staying thin, and appearing more mature, and they acknowledge negative aspects such as its making their teeth yellow, interfering with playing sports, being harder to quit, and causing bad breath.

Pharmacology

Human and animal studies confirm the addictive effects of nicotine, the primary active ingredient in cigarettes.7,8 It produces a syndrome of dependence and withdrawal. Nicotine is absorbed by multiple sites in the body, including the lungs, skin, gastrointestinal tract, and buccal and nasal mucosa. The average nicotine content of one cigarette is 10 mg, and the average nicotine intake per cigarette ranges from 1.0 to 3 mg. Nicotine, as delivered in cigarette smoke, has a half-life of 10 to 20 minutes, with an elimination half-life of 2 to 3 hours. Nicotine’s effect on the brain takes less than 20 seconds. The action of nicotine is mediated through nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. These receptors are located on noncholinergic presynaptic and postsynaptic sites in the brain. Cotinine is the major metabolite of nicotine via C-oxidation. It has a biological half-life of 19 to 24 hours and can be detected in urine, serum, and saliva.

Clinical Manifestations

Adverse health effects of smoking include chronic cough, increased mucus production, and wheezing. Smoking during pregnancy is associated with an average decrease in fetal weight of 200 g.9 Smoking in combination with the use of estrogen-containing oral contraceptives is associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction.10 Tobacco smoke induces hepatic smooth endoplasmic reticulum and, as a result, may also influence metabolism of drugs and of endogenously produced hormones. Phenacetin, theophylline, and imipramine are examples of drugs affected in this manner.

Treatment

Consensus panels recommend the use of the “five As” (ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange) and of nicotine replacement therapy in adults and adolescents, although evidence of efficacy in adolescents is limited. Nicotine patch studies to date in adolescents are suggestive of a positive effect on reducing withdrawal symptoms and that pharmacotherapy should be combined with behavioral therapy to reach higher cessation and lower relapse rates. Medications such as bupropion are not approved for use in anyone younger than 18 years; however, some pilot studies in adolescents report cessation efficacy. Clinical practice guidelines are available for practical office-based counseling strategies.11 Health supervision and supportive counseling are necessary components of smoking cessation management in adolescents and older adults, because relapse is common (Table 19-1).

TABLE 19-1 The Five As: Brief Strategies to Help Adolescents Quit Tobacco Use

| Ask | Systematically identify all tobacco users, as well as tobacco experience at every visit. |

From Houston TP, Adger H, Bavishi M: The AFP Guide to Teen Tobacco Use Prevention and Treatment, Illinois Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics and Illinois Department of Public Health, 2002.

ALCOHOL

By 12th grade, close to three fourths of adolescents in high school report having used alcohol at some point, 25% having had their first drink before age 13 years.12 The initiation of alcohol use at an early age is associated with an increased risk for alcohol-related problems. Although a legal drug, alcohol contributes to more deaths than do all the other illicit drugs combined. Among studies of adolescent trauma victims, alcohol is reported to be a factor in 32% to 45% of hospital admissions.13 Motor vehicle crashes are the most frequent type of event associated with alcohol use; the injuries reported span a wide variety, including self-inflicted wounds. Adolescents with alcohol-positive findings were also more likely to report a history of prior injury.2 A study by the Institute of Medicine calls for U.S. society at large to address the underage drinking crisis responsible for costly traffic fatalities, violent crime, and other negative behaviors in youth.14

Clinical Manifestations

Alcohol acts primarily as a central nervous system (CNS) depressant. It produces euphoria, grogginess, and talkativeness; impairs short-term memory; and increases the pain threshold. Alcohol’s ability to produce vasodilation and hypothermia is also centrally mediated. At very high serum levels, respiratory depression occurs. Alcohol’s inhibitory effect on pituitary antidiuretic hormone release is responsible for its diuretic effect. The gastrointestinal complications of alcohol use can occur as a result of a single large ingestion. The most common is acute erosive gastritis, which is manifested by epigastric pain, anorexia, vomiting, and guaiac-positive stools. Less commonly, vomiting and midabdominal pain may be caused by acute alcoholic pancreatitis; diagnosis is confirmed by the finding of elevated serum amylase and lipase activities.

In addition to the general risk factors noted for substance use, a positive family history of alcohol abuse is significant. The genetic influences for the predisposition to alcoholism are supported by family, twin, and adoption studies.15–18 Children of alcoholic parents demonstrate a threefold to ninefold increased risk for alcoholism.

OPIATES

Heroin is hydrolyzed to morphine, which undergoes hepatic conjugation with glucuronic acid before excretion, usually within 24 hours of administration. The route of administration influences the timing of the onset of action. When the drug is inhaled (“snorted”), almost 30 minutes are required before the desired effect is achieved. Ingestion through the subcutaneous route (“skin-popping”), produces the effect within minutes; when the drug is injected intravenously, the effect is immediate. Tolerance develops with regard to the euphoric effect and only rarely to the inhibitory effect on smooth muscle, which causes both constipation and miosis.

MDMA

MDMA is a synthetic, psychoactive drug chemically similar to the stimulant methamphetamine and the hallucinogen mescaline. Street names for MDMA include “ecstasy,” “XTC,” and “hug drug.” In high doses, MDMA can interfere with the body’s ability to regulate temperature. This can lead to a sharp increase in body temperature (hyperthermia), resulting in liver, kidney, and cardiovascular system failure. Research in humans suggests that chronic MDMA use can lead to changes in brain function, affecting cognitive tasks and memory. MDMA can also lead to symptoms of depression several days after its use. These symptoms may occur because of MDMA’s effects on serotonergic neurons. The serotonin system plays an important role in regulating mood, aggression, sexual activity, sleep, and sensitivity to pain. A study in nonhuman primates showed that exposure to MDMA for only 4 days caused damage of serotonin nerve terminals that was evident 6 to 7 years later.

Hallucinogens

TREATMENT

An individual is considered to have a “bad trip” when the setting causes the user to become terrified or panicked. These episodes should be treated by removing the individual from the aggravating situation or setting and attempting to reestablish contact with reality through calm verbal interaction. Any physical complications such as hyperthermia, seizure, or hypertension should be treated supportively. “Flashbacks”—LSD-induced states that occur after the drug has worn off—and tolerance to the effects of the drug are additional complications of its use.

FAMILY EFFECTS OF ALCOHOL AND OTHER DRUG USE

Children of Parents Affected by Substance Use Disorders

The familial effects of substance use disorders, particularly for alcoholism, are well documented. Approximately one fourth of all children in the United States younger than 18 years are exposed to familial alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence.19 Furthermore, it has been shown that children of an alcoholic parent are overrepresented in the mental health and general medical systems. They have higher rates of injury, poisoning, admissions for mental disorders and substance abuse, and general hospital admissions; longer lengths of stay; and higher total health care costs. Children of an alcoholic parent are at higher risk for learning disabilities. The effects of prenatal exposure to alcohol and the fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS)—the term generally applied to children who have been exposed and display a certain constellation of symptoms, such as growth retardation, CNS involvement to include behavioral and/or intellectual impairment, and characteristic facies (short palpebral fissures, thin upper lip, and elongated, flattened midface and philtrum)—are well known.

Some studies have demonstrated that parental alcoholism is associated with increased risk for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in offspring, conduct disorder, or anxiety disorders. These offspring have been shown to have more diagnosable psychiatric disorders (i.e., depression, ADHD, conduct disorder) and lower reading and math achievement scores.

Children of substance-abusing parents are at risk for neglect. These children appear to have more behavior disorders, anxiety disorders, poorer competency scores, and higher scores on both internalizing and externalizing subscales of the Child Behavior Checklist than do control groups of children.20,21 Other investigators have questioned whether the increased psychiatric problems seen in these children are caused by the parental substance abuse or by the comorbid psychiatric disorders in these parents.22 For example, there may be a link between both substance abuse and antisocial personality disorder (a frequent comorbid psychiatric disorder) in parents and conduct disorder in offspring or a link between both substance abuse and major depression in parents and conduct disorder in offspring.23,24 Finally, the children of substance-abusing parents are at extreme risk to abuse substances themselves. This increased risk arises from two phenomena: First, there is a genetic predisposition for the development of substance use disorders; second, these children often receive inadequate parental supervision, which itself is a risk factor for the initiation of substance abuse.25,26

Core Competencies for Addressing Children and Adolescents in Families Affected by Substance Use Disorders

National leaders from pediatrics, family medicine, nursing, social work, and adolescent health have previously collaborated in the development of a set of core competencies (Core Competencies for Involvement of Health Care Providers in the Care of Children and Adolescents in Families Affected by Substance Abuse) that outline the core knowledge, attitudes, and skills that are essential for meeting the needs of children and youth affected by substance use disorders in the family.27 These core competencies outline a model of practice and delineate the desired knowledge and skills of health professionals in this area. The model is an attempt to recognize and account for individual differences among health providers. Furthermore, it represents a recognition that although primary health and behavioral professionals may be responsible for identifying the problem, they should not be expected to manage it by themselves. Accordingly, three distinct levels of care are articulated that allow for flexibility of individuals to choose their role and degree or level of involvement (Table 19-2). A baseline or minimal level (level I) of competence is established, and all primary health care professionals should strive to achieve it. However, most developmental-behavioral pediatricians want and are expected to do more than is indicated in the level I competencies. For health professionals who desire competence at a higher level (levels II and III), a different and more advanced set of knowledge and skills is required.

TABLE 19-2 Core Competencies for Involvement of Health Care Providers in the Care of Children and Adolescents in Families Affected by Substance Abuse

EARLY IDENTIFICATION OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

In one study, 38% of Americans stated they had a family member with alcoholism.28 Because of its high prevalence and lack of socioeconomic boundaries, developmental-behavioral pediatricians should expect to encounter families with alcoholism and other drug use disorders routinely. Several studies suggest strongly that children of women who are problem drinkers have an increased risk of experiencing serious, unintentional injuries and that children exposed to two parents with alcohol problems are at even greater risk.29 Studies of the link between parental substance abuse and child maltreatment suggest that substance abuse is present in at least half of families known to the public child welfare system.30

Another study indicated that fewer than half of pediatricians ask about problems with alcohol when taking a family history.32 In contrast, Graham and colleagues33 found that patients wanted their physicians to ask about family alcohol problems and believed that the physician could help them and/or the abusing family member deal with their problems. A family history of alcohol and other drug abuse is more likely than many other aspects of history to affect a child’s immediate and future health. A thorough understanding of family members’ use of alcohol or other drugs is as important as a history for hypertension, cancer, or diabetes mellitus. In addition, family problems with alcohol or other drugs can jeopardize a parent’s ability to carry out necessary therapeutic regimens for their child.

Third, as adolescents grows older, it is increasingly important to identify their own alcohol and other drug use problems, because children from homes or who have parents with substance use disorders are at higher risk for developing their own problems with alcohol and other drugs.

INTERVIEWING CHILDREN, YOUTH, AND FAMILIES

Since the 1980s, there has been an increasing level of interest in, and appreciation for, the complexity of communication skills needed to establish effective physician-patient/family relationships. In efforts to organize concepts and knowledge about medical interviewing, investigators have established useful models for the medical interview.34 In one particularly useful model for child and adolescent health care, the medical interview is viewed as having three central functions: (1) to collect information regarding a potential problem; (2) to respond to the patient and family’s emotions; and (3) to educate the family and influence behavior.35 These functions are highly germane to the identification and intervention of children living with substance-abusing parents, because all three functions may need to occur simultaneously and are necessary to promote the well-being of these children adequately.

Collecting Information

To collect information about potential parental substance use disorders, health care providers need to (1) screen for and identify the family alcohol or drug problem; (2) understand the child’s response to his or her perceived situation; (3) monitor changes in the child’s behavior or health condition; and (4) provide themselves with a knowledge base regarding the child and family that is sufficient for developing and implementing a treatment plan. Children should be encouraged to tell their story in their own words. The physician may be required to help create or facilitate the child’s narration, to organize the flow of the interview, to use appropriate open- and closed-ended questions to clarify and summarize information, to show support and reassurance, and to monitor nonverbal cues.34 Health care providers need to acquire the knowledge base of psychosocial and family issues that contribute to the child or adolescent’s health condition. In addition, they may need to understand and respond to the child or adolescent patient and the family unit. Many children of substance-abusing parents display particular illness behaviors: that is, they develop a particular way of responding to their perceived overall situation. It is well established that children and youth, on the basis of individual and cultural differences, respond in different ways to similar biomedical and psychosocial conditions. Without an understanding of the psychological and social underpinnings of illness behavior, the clinician may fail to collect all the relevant information related to the child’s health problems.

Establishing Rapport

The second function of the interview involves the communication of interest, respect, support, and empathy between the clinician and the parent and between the clinician and the child or adolescent, with the goal of forming a relationship with the family.34,35 By recognizing and responding to the child and family’s emotional responses, the provider can ensure the child or family’s willingness to provide information and can ensure relief of the child’s physical or psychological distress. Attending to a child’s or family’s emotions is essential for effective communication and treatment planning with any emotionally complex issue, particularly one as potentially controversial as parental substance abuse. The clinician needs to hear the child’s (or the family’s) story with all its associated emotional distress. The emotions may range from fear to sadness, anger, or shame. The ability of a child or family member to verbalize these feelings in the presence of someone who can tolerate them and not be frightened is, in itself, therapeutic. A nonusing but affected parent may be as confused and frightened about the problem as the child. The open communication of fear and anxiety has been found to be related to satisfaction and compliance.36 The empathic clinician, by understanding the child’s situation, can decrease the child’s and family’s anxiety, thereby increasing their trust, with associated willingness to offer more complete information and follow through with treatment recommendations.

Education and Behavior Change

Dealing with parental substance abuse requires education of the family and behavior change for the young patient but also for all family members. The third function of the medical encounter must build on the successes of the first two functions. Care must be taken to ensure the child’s and family’s understanding of the nature of addiction, its influence on family function and individual family members, and its role in undermining a child’s health. The physician will probably need to negotiate additional assessment or treatment of family members, as well as a specific treatment plan for the child’s physical and mental conditions. Emphasis may need to be placed on the child and family’s coping styles and simple first-pass efforts at lifestyle change. This requires understanding and working with the social and psychological consequences of the parental substance use disorder.

A DEVELOPMENTAL LIFESPAN PERSPECTIVE ON SCREENING

Infancy and Early Childhood

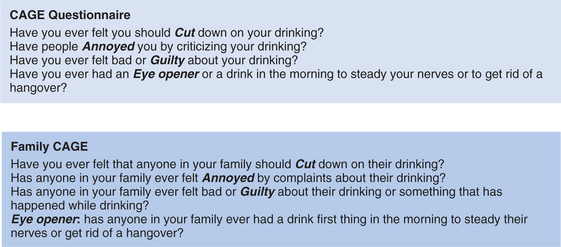

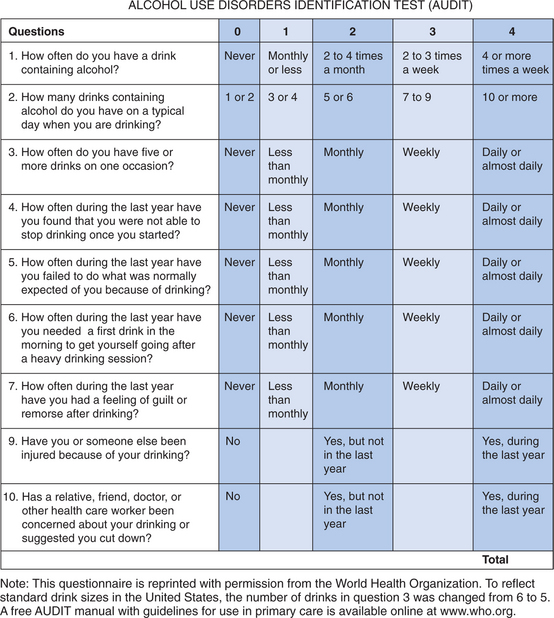

During a child’s infancy and early childhood, the target of screening efforts continues to be the parents. A good way to begin an interview with a parent may be by asking, “How are things going for you?” When verbal or nonverbal responses indicate depression, fatigue, unhappiness, or other emotional or interpersonal discomforts, it may be useful to pursue the underlying causes such as personal or spousal substance use. For example, “People handle stress in different ways. Some people exercise, some sleep, some people eat more, others smoke cigarettes or use alcohol or other drugs. How are you handling it?” The objective during infancy and early childhood is to reduce the amount and frequency of ATOD use occurring in the family and to which the young child is exposed. Child health care providers should learn about the alcohol and other drug use habits of all parents of infants and young children. This can be done in the context of a global family health assessment. Emphasis should be placed on how alcohol or drug use can affect parenting decisions, exacerbate stress and marital problems in the home, create a potentially unsafe home environment, and model drug use behaviors for children. The use of established screening tools such as the CAGE questionnaire (to be described) and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) may be helpful (Figs. 19-1 and 19-2).37–40 If parents already have made a change in their alcohol or other drug use habits, this change should be reinforced. At a minimum, screening young adult parents for substance use disorders raises an important issue, gives feedback to the parents, and establishes the willingness of the provider to discuss the issue at a later time, if needed.

FIGURE 19-2 Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT).

(From the World Health Organization. To reflect standard drink sizes in the United States, the number of drinks in question 3 was changed from 6 to 5. A free AUDIT manual with guidelines for use in primary care is available online at www.who.org.)

Adolescence

Families continue to exert significant influence on adolescents and on the behaviors in which teenagers choose to engage. Early identification of families with alcohol- or drug-related problems is crucial for preventing substance abuse among adolescents themselves. Family issues to address include parent-child interactions and maladaptive family problem solving, which often involve avoidance of issues and conflict.41,42 Families with marital discord, financial strains, social isolation, and disrupted family rituals (such as mealtimes, holidays, and vacations) also increase an adolescent’s risk of problematic alcohol use.43 Adolescents are particularly at risk if parents are either excessively permissive or punitive or if parents offer little praise or seem persistently neglectful of the adolescent.

Clear parent-defined conduct norms are an important protective factor.42,44,45 Adolescents least likely to use alcohol or other drugs are emotionally close to their parents, receive advice and guidance from their parents, have siblings who are intolerant of drug use, and are expected to comply with clear and reasonable conduct rules. The parents of nonusers typically provide praise and encouragement, engender feelings of trust, and are sensitive to their children’s emotional needs. Alcohol and/or other drug use should be included as a primary consideration in all behavioral, family, psychosocial, or related medical problems. The identification and assessment of high-risk behaviors and predisposing risk factors are key aspects in the early recognition of alcohol-related problems. As a routine part of the adolescent’s visit, there should be an assessment of risk by reviewing risk factors and behaviors with youths and their parents.

APPROACHES TO SCREENING

Screening for Alcohol- or Drug-Related Problems in the Family

In many instances, family problems related to alcohol and drug use are subtle and identifying them requires a deliberate and skilled screening effort. On the basis of the nature of a presenting medical problem or as a result of problem areas in the psychosocial history, screening may involve asking the child or adolescent patient questions directly, asking questions that are developmentally appropriate, and addressing their perceptions of problematic substance use in the family. The clinician can begin by asking a simple but important screening question: “Have you ever been concerned about someone in your family who is drinking alcohol or using other drugs?” This question sets the groundwork for possible later discussion. It also lets the family and the child or adolescent know that the clinician believes that use of alcohol and other drugs is a health concern and that the clinician is willing and able to assist the family. (The Web sites for the National Association for Children of Alcoholics [www.nacoa.org] and Contemporary Pediatrics [http://www.contemporarypediatrics.com/contpeds/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=141246] provide an extended discussion of strategies, tools, resources, and tips on organizing the office visit.)

Because of the high prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use, many authorities recommend that all adults be screened with a validated survey instrument such as the CAGE questionnaire (for which each letter in the acronym refers to one of the questions) or the AUDIT.46 The CAGE questionnaire is brief but was designed primarily to detect dependence. The AUDIT is longer but detects a spectrum of unhealthy drinking (see Figs. 19-1 and 19-2).

The CAGE questionnaire is a four-item alcohol screening instrument with demonstrated relevance for primary care in clinical, educational, and research settings (see Fig. 19-1).37–39 The questions concern whether the respondent has ever needed to cut down on their drinking, felt annoyed by complaints about his or her drinking, felt guilty about his or her drinking; or had an eye-opener—that is, a drink—first thing in the morning.

One technique for maximizing the usefulness of responses to screening questions is to apply them to all members of the household. The Family CAGE is a modified version of the commonly used CAGE questionnaire that simply broadens the standard CAGE items to include “anyone in your family” (see Fig. 19-1). The Family CAGE questions can be used to provide a proxy report regarding another individual, such as a parent or an older sibling. For example, if the patient is a 12-year-old who currently is not using alcohol or other drugs but is concerned about a parent’s use of alcohol, the health care professional could screen for concerns about the parent’s alcohol use by asking the child the CAGE questions in the following manner: “Do you think your mother needs to cut down on her alcohol use? Does your mother get annoyed at comments about her drinking? Does your mother ever act guilty about her drinking or something that happened while she was drinking? Does your mother ever have a drink early in the morning as an eye-opener?” One or more positive answers to the Family CAGE can be considered a positive screen result, and additional assessment is needed. The Family CAGE is intended to screen for alcohol problems in families, not to diagnose family alcoholism. A positive finding on the Family CAGE implies a greater relative risk for alcoholism in the family and should be followed by a more thorough diagnostic assessment. In one study, one positive response on the Family CAGE was more sensitive than a question about perceived family alcohol problems.47 The specificity of the Family CAGE for family alcohol problems was 96%; the positive predictive value, 90%; the sensitivity, 39%; and the negative predictive value, 62%.47 The Family CAGE results are also correlated with the degree of family stress, of family communication problems, and of marital dissatisfaction and with use of drugs other than alcohol. The ability to use the Family CAGE in this manner offers the potential for great flexibility for the pediatric encounter and provides a comfortable way of collecting pertinent screening information about or from children or adolescent patients and parents. By substituting the words drug use for drinking, the Family CAGE also can be used to screen for problematic use of drugs other than alcohol.48

Screening for the Effect of Family Substance Abuse

A longer written screening tool that may be useful is the Children of Alcoholics Screening Test.49,50 This test was developed as an assessment tool that could identify older children, adolescents, and adult children of alcoholics. It is a 30-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure patients’ attitudes, feelings, perceptions, and experiences related to their parents’ drinking behavior, using a “yes”/“no” format. It may be useful when a written questionnaire is the preferred method with older children or adolescents.

The Family Drinking Survey also addresses how family members have been affected by a family member’s alcoholism.51 It is adapted from the Children of Alcoholics Screening Test, the Howard Family Questionnaire, and the Family Alcohol Quiz from Al-Anon and is suitable for use with adolescent patients or nonusing parents. It addresses the effects of family alcoholism on the patient’s emotions, physical health, interpersonal relationships, and daily functioning. Many substance-abusing parents themselves are children of substance abusers. Inquiring about family histories of addiction while completing a three-generation genogram with parents can help them put their own substance abuse in an intergenerational context. This motivates some parents to seek treatment to prevent passing this self-destructive behavior on to their own children as their parents did to them. Acknowledging their own childhood experiences can also sensitize parents to the emotional devastation they are causing their children.

An important consideration of children, youths, and parents is the confidentiality of the information gathered. Although many family members are eager to facilitate help for the alcoholic family member, others are more reluctant. If the presenting child or adolescent patient or nonusing parent is reluctant to share his or her concerns, the physician can encourage individual counseling. Attendance at meetings of Al-Anon, Alateen, or Adult Children of Alcoholics groups is important for family members. Whether the family member affected does or does not obtain treatment, other family members may need to learn to care for themselves, and 12-step programs can be extremely supportive.

Screening Measures for Older Adolescents or Adult Family Members

The signs and symptoms of alcohol and other drug abuse in adolescents often are subtle. More telling than physical signs may be the indication of dysfunctional behaviors. A sudden lapse in school attendance, falling grades, or deterioration in other life areas may become more apparent as alcohol or other drug use escalates.52 Often problems with interpersonal relationships, family, school, or the law become more evident as use increases. Depressive symptoms such as weight loss, change in sleep habits and energy level, depressed mood or mood swings, and suicidal thoughts or attempts may be presenting symptoms of alcohol or other drug use. A general psychosocial assessment of an adolescent’s functioning is the most important component of a screening interview for alcohol misuse or abuse. It may be helpful to begin with a discussion of general topical areas, including home and family relationships, school performance and attendance, peer relationships, recreational and leisure activities, vocational aspirations and employment, self-perception, and legal difficulties. The information gathered helps determine whether alcohol or other drug use is a cause of behavioral dysfunction and the degree of patient impairment.

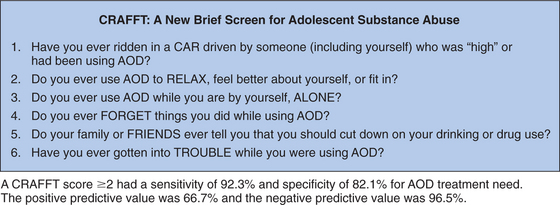

Although no single measure has been recommended for screening adolescents, the CRAFFT questionnaire (whose acronym is based on the questions) (Fig. 19-3), a brief screening tool that has been validated in adolescents, has been used by many clinicians and is easy to use.53 Others find tools such as the AUDIT to be helpful because they incorporate questions about drinking quantity, frequency, and binge behavior, along with questions about consequences of drinking. A more detailed discussion of adolescent substance abuse screening and assessment is available in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Treatment Improvement Protocol.54

EARLY INTERVENTION FOR SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

Developmental-behavioral pediatricians and others can have a major influence on families when there is an alcohol- or drug-related concern. Health providers can screen for problem use; offer interventions, support, information, and referrals; and provide guidance and direction for children at risk. Early intervention is a transitional component in the continuum of substance abuse care, between prevention and treatment, and can be distinguished in terms of target population and specific objectives.55 A useful definition of early intervention would include services directed at (1) individuals or families whose use of ATOD places them or other family members at an unacceptably high level of risk for negative consequences, (2) individuals whose use of ATOD has resulted in clinically significant dysfunctions or consequences for themselves or family members, and (3) individuals or families who exhibit specific problem behaviors hypothesized to be precursors to ATOD problems. In the case of children of substance-abusing parents, an early intervention for the parent and family also should be viewed as prevention for the child. In addition, interventions by primary care providers, which lead to changes in the family’s functioning and overall health, can be seen to affect the entire family.

HEALTH AND NEURODEVELOPMENTAL OUTCOME STUDIES OF CHILDREN WITH INTRAUTERINE DRUG EXPOSURE

At the individual level, a parent with a history of drug dependence may impart genetic and environmental risk factors that contribute to poor neurobehavioral and neurodevelopmental outcomes in his or her children.56–59 There is a higher incidence of childhood-onset ADHD and conduct disorder in individuals with alcohol and illicit drug dependence than in those without substance abuse disorders.60,61 Women who become dependent on alcohol or drugs are shown to have had higher rates of depression, suicidal behavior, anxiety, and withdrawn behaviors during childhood.57,62 In addition, women who abuse drugs are more likely to have experienced physical abuse and sexual abuse than their non-drug-dependent peers.63

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Related Disorders

FAS is one of the leading identifiable and preventable causes of mental retardation and birth defects, occurring in 0.2 to 1.5 infants per 1000 live births in the United States.64 Approximately 4 million infants each year are estimated to have been exposed to alcohol during gestation. It is estimated that 20% of pregnant women drink occasionally and fewer than 1% drink heavily. FAS occurs in 30% to 40% of pregnancies in which a women drinks heavily (more than one drink of 1.5 oz of distilled spirits, 5 oz of wine or 12 oz of beer per day). Although there is evidence of a dose response effect of alcohol on the developing fetus, no safe amount of alcohol consumption during pregnancy has been identified. Of importance is that FAS is 100% preventable; if a mother-to-be does not drink alcohol during pregnancy, her child will not have FAS.

FAS is associated with physical characteristics that include growth retardation, microcephaly, short palpebral fissures, flat midface, long philtrum, and thin upper lip.65 A stepwise discriminant analysis of three facial features (ratio of reduced palpebral fissure length to inner canthal distance; smoothness of the philtrum; and thinness of the upper lip) identified children with FAS with 100% accuracy.66 Sensitivity and specificity for identification of FAS by the three facial features were unaffected by race, age, and gender. CNS anomalies may include agenesis of the corpus callosum and cerebellar hypoplasia.67

Multiple studies have demonstrated alcohol’s neurobehavioral teratogenic effects. Neuropsychological disorders associated with alcohol exposure include ADHD, depression, suicidal ideation, mental retardation, and learning disabilities.68–71 Children with intrauterine alcohol exposure also are at risk for poor motor coordination, social functioning, and judgment that may place the child at further risk for poor school performance.68

In 1996, the Institute of Medicine proposed using the terms alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder and alcohol-related birth defects to describe the spectrum of clinical findings associated with alcohol exposure.72 Furthermore, in 2004, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention73 released a report containing diagnostic criteria for FAS, including recommendations for prevention of alcohol exposure during pregnancy. There is currently general consensus that prenatal alcohol exposure results in a wide range of adverse effects that, as a whole, have been called fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Birth defects associated with alcohol exposure affect multiple organ systems. The most common alcohol-related malformations include cardiac anomalies (e.g., atrial septal defects, ventricular septal defects, tetralogy of Fallot), skeletal anomalies (e.g., hypoplastic nails, shortened fifth digits, scoliosis, hemivertebrae, Klippel-Feil syndrome, radioulnar synostosis), renal anomalies (e.g., aplastic or dysplastic kidneys, horseshoe kidneys), ocular anomalies (e.g., strabismus, retinal vascular anomalies), and auditory impairments.

The annual U.S. cost of alcohol related disorders ranges from $75 million to $249.7 million.74,74a). Approximately 60% to 75% of the cost is attributable to care of individuals with FAS who have mental retardation. An estimated $75 million per annum is spent for supervised environments for individuals with IQs in the range of 70 to 85.74a

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Web site (http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fas/faqs.htm) that answers frequently asked questions about FAS. Additional educational resources for caregivers and providers of services for children with fetal alcohol syndrome spectrum disorders include the Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Family Resource Institute (1-800-999-3429) http://www.fetalalcholsyndrome.org.

Tobacco

Nicotine, a colorless liquid alkaloid, is the active ingredient in tobacco. Ninety percent of nicotine is absorbed from inhalation, and the liver subsequently metabolizes 80% to 90% of the nicotine. The physiological effects of smoking one cigarette are similar to injecting 1 mg of nicotine intravenously.75). Nicotine is one the most toxic drugs known. It binds to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the fetal brain, causing disruption of synaptic activity, cell loss, and neuronal damage. It has been determined that fetuses in the second and third trimesters are particularly susceptible to the negative effects of tobacco exposure, inasmuch as the number of nicotine receptor binding sites tends to increase significantly during these periods.76

Other biological studies indicate that carbon monoxide and nicotine lower maternal uterine blood flow by up to 38%.9 This in turn reduces the concentration of oxygen in maternal tissues and fetal cord blood, thereby leading to fetal hypoxia and malnutrition. This chronic hypoxia may disrupt neuronal pathways and impair cognitive development.77,78

The teratogenic effects of smoking tobacco and passive transmission through environmental tobacco smoke are extensively documented in the literature. Children exposed to nicotine in utero have an increased risk for low birth weight, defined as birth weight of less than 2500 g.79 This increased risk, resulting from intrauterine growth retardation, demonstrates a dose-response relationship at the rate of 5% weight reduction per pack of cigarettes smoked per day.78 These infants weigh approximately 150 to 250 g less than non-tobacco-exposed infants and account for 20% to 30% of all infants with low birth weight.9

Inadequate fetal lung development and poor neonatal pulmonary functioning are associated with prenatal exposure to tobacco. Jaakkola and Gissler79 tested the causal effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on asthma development in childhood in a population-based cohort of Finnish singleton births (N = 58,841). These authors postulated that the direct effect of prenatal smoking on the risk for development of asthma in the first 7 years of life would be partially mediated by the presence of intrauterine growth retardation and preterm delivery. The results demonstrated that children whose mothers smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day during pregnancy had a 36% higher chance of developing asthma in the first 7 years of life. There appeared to be a small reduction in the direct effect when intrauterine growth retardation and preterm delivery were added to the model, which suggests that these mediating factors account for only a small proportion of the effect.

NEURODEVELOPMENTAL OUTCOME

Law and colleagues9 examined the effects of smoking during pregnancy on neurobehavioral functioning in newborns. The NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale80 was completed for 56 neonates 48 hours after birth. Examiners were unaware of the prenatal smoking exposure status of the infants. Maternal smoking was measured through the Timeline Follow Back interview of smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy81 and salivary cotinine bioassay. The results were suggestive of neurotoxic effects of in utero tobacco exposure on neurobehavior. Specifically, the exposed infants showed evidence of increased excitability, hypertonia, and stress/abstinence symptoms in the CNS, gastrointestinal system, and visual field. These findings were demonstrated at a dose rate (6 cigarettes per day) lower than the 10 cigarettes per day that is traditionally cited in the literature on the dose-response relationship. The authors noted that establishing these neuroteratogenic effects at birth may provide compelling evidence for the role of prenatal tobacco exposure, over and above postnatal contextual factors, on the development of long-term deficits such as lower IQ and ADHD.

Cornelius and associates76 examined the longitudinal effects of prenatal smoking on neuropsychological functioning in a sample of 593 children. Participants were monitored prospectively from the fourth month of gestation to age 10 years. Neuropsychological tests were conducted at the 10-year follow-up to assess the effect of gestational smoking on learning, memory, problem solving, mental flexibility, attention, and eye-hand coordination. These longitudinal data demonstrated an adverse effect of gestational smoking on learning, memory, problem solving, and eye-hand coordination. These results remained statistically significant even when other prenatal and current maternal substance abuse, demographic, psychological, and environmental variables were accounted for. Fried and coworkers82 found that prenatal cigarette exposure was negatively associated with overall intelligence in a sample of 145 adolescents aged 13 to 16 years old.

Prenatal nicotine exposure is also associated with deficits in language development.78 Results from the Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study83 revealed that children prenatally exposed to cigarettes had decreased responsiveness on auditory items on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) at 12 and 24 months of age. Delays in language development continued to exist at age 4 years. Cognitive deficits, specifically on measures of verbal intelligence, reading, and language, continued to persist into early adolescence, which constitutes further evidence of the dose-dependent response noted at earlier ages.84

The literature clearly demonstrates that prenatal tobacco exposure is a risk factor for development of behavior problems, specifically aggressive and antisocial behaviors.85 This relationship also seems to follow a dose-response effect between the amount of prenatal exposure and the emergence of behavior problems.78 Of importance is that although researchers have attempted to account for confounding factors when analyzing the statistical relationship between prenatal exposure and childhood conduct problems, the strength of the relationship relies primarily on correlational data. The effect of the relationship appears to be reduced when other known confounding factors are analyzed.

Silberg and colleagues86 tested the causal relationship between prenatal tobacco exposure and childhood conduct disorder in a sample of 538 white male twins. General linear models were used to examine the direct effect of prenatal smoking on childhood conduct disorder. Mothers’ conduct disorder symptoms in childhood were included as an operationalization of the latent variable “antisociality.” The effects of prenatal smoking were significantly reduced when mothers’ childhood conduct disorder symptoms and age were included in the model.

Cocaine

Cocaine use during pregnancy is associated with adverse outcomes that include higher risk of sexually transmitted disease and of pregnancy-related complications such as premature rupture of membranes, abruption of the placenta, and fetal demise in comparison with women without a history of cocaine use.87,88 In a case-control study of 400 maternal-infant dyads (200 with maternal cocaine use and 200 without drug use),87 infants born to mothers with a history of cocaine use had a significantly higher risk of having respiratory distress syndrome, congenital syphilis, and prolonged hospital stay.

NEURODEVELOPMENTAL OUTCOME

Early case reports led to many premature conclusions about neurodevelopmental outcome of children with intrauterine cocaine exposure. One meta-analysis of 118 studies of children with intrauterine cocaine exposure demonstrated that 92% of the studies included children with exposure to multiple drugs, including alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and opiates.89 Over time, more sophisticated techniques were developed to identify and quantify cocaine and other drug use, and data collection and statistical analyses improved.

Impairment of brain growth in children with intrauterine cocaine/polydrug exposure (IUDE) is documented in multiple studies.90–93 Disturbances of neuronal migration and differentiation have been reported in human infants exposed to cocaine during gestation.94,95 The most common neurological anomaly found in children with cocaine/polydrug exposure is microcephaly.96

In a study of children with cocaine/polydrug exposure, mean birth head circumference for infants with only cocaine exposure was 1.71 standard deviations smaller than the mean, whereas head circumference was 1.0 and 1.52 standard deviations below the mean for infants exposed only to opiates and those exposed to cocaine and opiates, respectively.92 Preliminary data from a small case-control magnetic resonance imaging study suggested smaller white matter volumes in the frontal lobes of children with cocaine or polydrug exposure than in those of children without drug exposure.97 Midline prosencephalic developmental abnormalities, including agenesis of the corpus callosum, septo-optic dysplasia, and absence of the septum pellucidum, have been reported in case studies of children with intrauterine cocaine exposure.98

Cranial ultrasound data obtained during the neonatal period demonstrated that 35% of infants with intrauterine cocaine or polydrug exposure had one or more intracranial abnormalities.99 Ultrasound findings were suggestive of degenerative changes or focal infarctions of the basal ganglia. In addition, schizencephaly and neuronal heterotopias have been documented in children born to cocaine-dependent mothers.94,95,98

Differences in attention, distractibility, and visual memory have been reported in infants with cocaine or polydrug exposure.100–103 Studies of young school-aged children with IUDE have documented significantly higher externalizing (e.g., inattention, aggression, disruptive behavior) and internalizing behavior problems (e.g., withdrawn, anxious behaviors). Delaney-Black and associates104 demonstrated gender and duration-specific effects of prenatal cocaine, finding that behavior of school-aged boys was more significantly and negatively affected by cocaine exposure than that of girls. In a study of 145 children (111 with IUDE and 34 nonexposed children) by Butz and coworkers,105 parents and caretakers of children with intrauterine drug exposure reported significantly more overall behavior problems, especially anxious or depressed behaviors and deficits in attention in their children. In addition, stress levels were higher in caretakers of children with intrauterine drug exposure than in those of children without drug exposure.102

A longitudinal case-cohort study of 476 children (253 cocaine-exposed and 223 non-cocaine-exposed infants) documented performance deficiencies on measures of visual attention in 7-year-old children with intrauterine cocaine exposure, after adjusting for medical and sociodemographic variables and for alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco exposure.100

In a meta-analysis of 36 studies that met stringent criteria, including using only prospective controlled studies whose evaluators were unaware of drug of exposure and whose participants included children with cocaine exposure, without substantial opiate, amphetamine, or phencyclidine exposure, Frank and associates106 concluded that if exposure to other drugs was controlled statistically or in the study design, prenatal cocaine exposure was not found to contribute to growth retardation. In addition, the majority of studies in which researchers controlled for other drug exposure did not reveal an association between intrauterine cocaine exposure and adverse cognitive and language outcomes. Three of the six studies analyzed demonstrated deficient motor skills in the first 7 months. Of most significance, findings did support a relationship between cocaine exposure and less affective expression during infancy and early childhood, as well as less optimal scoring on behavior rating scales and tests of sustained attention.

The Maternal Lifestyle Study is a prospective, longitudinal, multisite study (funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Administration on Children, Youth and Families; and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment) to determine the association between cocaine and opiate exposure and developmental and behavioral outcome; a host of medical and psychosocial covariates are controlled.89 Phase I, conducted between 1993 and 1995, included 11,811 mother-infant dyads. Meconium samples were collected from the infants for enzyme-multiplied immunoassay for cocaine, opiates, tetrahydrocannabinol, amphetamines, and phencyclidine, followed by gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy confirmation. In phase II, 1388 mother-infant dyads with and without drug exposure and matched for race, gender, and gestational age from the pool of 11,811 were studied. After adjustment for other drug exposure, results from the 1-month evaluation demonstrated subtle but consistent differences, including lower arousal, poorer quality of movement and self-regulation, increased hypertonia on the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale, and longer interpeak intervals I to III and shorter interpeak intervals III to V on auditory brain response testing. At 3 years of age, cocaine exposure was not associated with BSID-Second Edition Mental Developmental Index, Psychomotor Developmental Index, or Behavior Record Scale scores.107

Marijuana

One large prospective study of more than 7000 pregnant women revealed no associations between marijuana use during pregnancy and low birth weight, preterm delivery, or abruptio placentae.108 Another study of more than 700 infants revealed no increased incidence of pregnancy, labor, or delivery complications in association with marijuana use during pregnancy.109 In addition, two large prospective studies—the Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study (OPPS)110 and the Maternal Health Practices and Child Development Projects (MHPCD)109—provide much of the knowledge about the effects of intrauterine marijuana exposure. Initiated in 1978, the OPPS is an ongoing longitudinal investigation of 190 children born to middle class, primarily college-educated women, of whom 140 had a history of marijuana use during pregnancy and 50 did not. The MHPCD recruited 763 primarily low-income women from Pittsburgh during the fourth month of pregnancy from 1983 to 1985 to monitor the developmental outcome of their children with and without exposure to marijuana and alcohol.109

These studies, along with others, revealed that marijuana use during pregnancy was not associated with fetal growth retardation.109–111

NEURODEVELOPMENTAL OUTCOME

Neonatal findings reported in infants with prenatal marijuana exposure include increased tremors and startles, abnormal sleep patterns characterized by decreased quiet sleep, and poorer habituation to light.109,110). Interestingly, in a prospective study of 24 Jamaican infants with marijuana exposure who were compared with nonexposed neonates, there were no differences between the groups on day 3, when the infants were assessed with the Brazelton Neonatal Assessment Scale, and at 1 month. Infants with heavy marijuana exposure demonstrated improved autonomic stability, quality of alertness, less irritability, and better self-regulation. Dreher’s112 study is important because the neonates in this study were generally exposed to higher potency marijuana and were less likely to be exposed to other drugs than were neonates in U.S. and Canadian studies.

Outcome evaluation of 12- and 24-month-old children with intrauterine marijuana exposure enrolled in the OPPS revealed no association between the BSID scores and marijuana exposure after home environment was controlled for. Marijuana exposure was negatively correlated with the home environment.113

Unadjusted hierarchical regression analyses of young elementary school-aged children with second trimester intrauterine marijuana exposure revealed that these children had more errors of commission on the Continuous Performance Test,114 which was suggestive of increased impulsivity in marijuana-exposed children in comparison with children with no exposure.115 At 10 years of age, children with heavy marijuana exposure during the first trimester had lower scores on the design memory and screening index of the Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning116; in addition, the finding of increased commission errors persisted.117 The magnitude of the marijuana effects were small at this age, and on structural equation modeling, there were no significant associations between marijuana exposure and neuropsychological domains.117 Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of young adults, 18 to 21 years of age, with prenatal marijuana exposure demonstrated increased neural activity in bilateral prefrontal cortex and right premotor cortex and decreased cerebellar activation during response inhibition.118 More commission errors continued to be present in young adults exposed to marijuana.118

In summary, intrauterine marijuana exposure appears to be associated with persistent deficits in prefrontal lobe functioning, as evidenced by both the longitudinal MHPCD and OPPS. As a result, children with intrauterine marijuana exposure have deficiencies in the stability of attention (e.g. the ability to maintain attention over time), as well as impulsivity.115,119

Opiates

The majority of studies suggest that infants with intrauterine opiate exposure weigh less and have smaller head circumferences than do their non-drug-exposed peers.120–124 Infants with gestational opiate exposure have been reported to have a higher incidence of respiratory distress and infections and longer hospitalizations, attributable to withdrawal- and non-withdrawal-related morbidity.121,122,124

One of the major morbid conditions in infants with in utero opiate exposure is neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), or neonatal drug withdrawal. NAS is characterized by CNS and gastrointestinal symptoms, including irritability, tremors, disrupted sleep patterns, rigidity, seizures, poor suck, vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, poor weight gain, temperature instability, and diaphoresis.125–128

The incidence of NAS varies in frequency and onset, depending of the dose and type of maternal opiate use.120,122,129 Because of methadone’s 15- to 57-hour half-life, neonatal withdrawal may not be observed until 72 hours after birth; however, the onset may be protracted and can occur up to 4 weeks after birth. In contrast, withdrawal from heroin is usually evident within 24 to 72 hours. Symptoms of NAS may be measured by a variety of instruments, including those developed by Finnegan127 and Lipsitz130 to determine whether pharmacological management is necessary.

Phenobarbital and diazepam have also been used to treat NAS. Phenobarbital reduces the irritability, tremulousness of NAS but does not control gastrointestinal signs. Poor feeding, weight gain, and feeding time was noted during phenobarbital therapy for NAS in comparison with paregoric. In addition, phenobarbital may cause CNS depression. In a study by Kaltenbach and Finnegan,129 infants with NAS initially treated with phenobarbital were more likely to require a second drug to control NAS than were those treated with paregoric. A phenobarbital loading dose of 16 mg/kg in 24 hours controlled most narcotic symptoms, with maintenance doses of 2 to 8 mg/kg/day. Diazepam, 1 to 2 mg of every 8 hours, may result in rapid suppression of NAS signs; however, diazepam may cause CNS depression, poor suck, and late-onset seizures.

NEURODEVELOPMENTAL OUTCOME

A comparison of paregoric, phenobarbital (loading), phenobarbital (titration), diazepam, and no treatment (for infants with mild NAS symptoms) in infants with opiate exposure demonstrated no differences among the groups on the 6-month BSID Mental Developmental Index score.129 In a longitudinal study of 39 infants (16 methadone-exposed infants and 23 non-drug-exposed infants) in which partial-order scalogram analyses were used to study the differences among the scores on the subtests of the Infant Behavior Rating, only motor coordination was different between the methadone-exposed and non-drug-exposed infants at 4 months, after family and medical risk factors were adjusted. By 12 months, the attention subtest distinguished between the two groups of infants.131 Rosen and Johnson123 studied 64 children, of whom 41 had been exposed to methadone and 23 had not been exposed, at ages 6, 12, and 18 months. At 12 and 18 months, significant differences, favoring the non-drug-exposed infants, were found in mean Mental Developmental Index and Psychomotor Developmental Index scores on the BSID. In the Maternal Lifestyle Study of children with cocaine and opiate exposure, 1227 infants (474 with cocaine exposure, 50 with opiate exposure, and 48 with cocaine and opiate exposure) were evaluated through 3 years of age.107 Opiate exposure was not associated with overall Mental Developmental Index score at 2 or 3 years of age.

PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

Home-based nursing intervention is one type of community-based educational intervention used for women who are drug dependent and for their children. By providing education, access to services, and enrichment experiences in the natural environment, home-based intervention are designed to promote the health and well-being of children and families at risk for poor developmental outcomes. Nurses are especially suited to provide intervention because of their expertise in the areas of women’s and children’s health, their capacity for handling complex clinical issues, and their ability to teach health awareness while improving access to medical care.132

Black and associates133 examined the effect of a home intervention designed to support parenting and child development through the first 18 months post partum. Modest improvements were noted in recovery, emotional responsiveness of the mother, and attitudes toward parenting for the women in the intervention. There were no developmental differences between the intervention and control children at the 18-month follow-up. The findings revealed only modest changes on drug use and parenting behaviors as a result of the home intervention. In another randomized study of home-based nursing intervention for a cohort of 100 children with intrauterine drug exposure,134 mothers perceived that children who received home-based nursing intervention had significantly fewer behavior problems.

Hofkosh and coworkers135 found a similar pattern of results, noting that the developmental capabilities of the children in their home-based clinical intervention were age appropriate at 1 year. These authors noted that the ability of the mother to provide a developmentally supportive environment most significantly affected child development.

Schuler and associates136 conducted a home-based nursing intervention for 131 women with active substance abuse problems up to 24 months after delivery. A preintervention-postintervention randomized control design was used with follow-up assessments at 6-month intervals through 24 months and yearly thereafter. The program was divided into two components. The parent component focused on teaching the parent to identify and to appropriately use family, community, and social systems for a range of services, including public assistance, domestic violence, and drug treatment. The child component focused on enhancing maternal-child relations by teaching parents how to play with their children in order to promote age-appropriate developmental skills. This home-based nursing intervention entailed a combination of the Infant Health and Development Program and the HELP at Home curriculum from the Hawaii Early Learning Program137 that was modified to apply specifically to substance-abusing mothers and their children. Results indicate that children in the early intervention group demonstrated significant improvements in motor and mental development in comparison with children in the control group up to 18 months post partum. There were no differences between the groups on language development. Mothers receiving the intervention and mothers in the control group had similar rates of ongoing drug use: 43% and 36%, respectively.

There was no significant effect of the home-based intervention on maternal-child relations as operationalized by maternal competence and observed child responsiveness during mother-child interactions at the 18-month follow-up.138 A sample of 108 cocaine-abusing mothers using the same home-based intervention139 exhibited significant improvements in cognitive scores on the BSID after the home-based intervention. Ongoing maternal drug use was associated with poor infant cognitive developmental outcomes through 18 months post partum. These results suggest that ongoing maternal drug use is a critical environmental factor that appears to adversely affect the outcome of intervention trials in children exposed to IUDE.

Other types of treatment approaches to improve maternal-child relations with drug-dependent mothers have focused on inclusion of multiple treatment methods within one model to provide a more comprehensive and holistic drug treatment approach. McComish and colleagues140 evaluated the efficacy of a family-focused residential drug treatment program for drug-dependent women and their children. Significant improvements in the mother’s parenting knowledge and treatment retention were noted. This study also demonstrated the importance of inclusion of children in early intervention with drug-dependent mothers. Although the children in the intervention did not initially show signs of developmental delay, longitudinal data revealed signs of motor and language delay for some of the children in the intervention group. Thus, early detection and, consequently, early treatment of developmental delays occurred in the children as a result of their participation in this comprehensive residential program.

Although most studies have focused on adult mothers, substance abuse among mothers younger than 20 years is also an important public health concern. Studies show that young drug-abusing mothers are at increased risk for parenting problems because of a variety of factors, including lack of parenting experience, less education, and lack of financial resources. Furthermore, these mothers may have their own problems understanding and developing basic psychoemotional developmental skills such as developing trust, problem solving, and impulse control.141 Field and coworkers142 examined the effect of a multimodal intervention for adolescent mothers and their children with IUDE. The participants in this study attended a 4-month treatment program located within their vocational school. Mothers received drug and social rehabilitation, parenting and vocational courses, and relaxation therapy. Infants were placed in a nursery while their mothers attended high school or General Educational Development (GED) preparation classes. The mothers volunteered as teacher-aid trainees in the nursery and learned parenting skills while tending to their babies. At the 6-month follow-up, the mother-child interactions and child developmental outcomes of mothers and infants in the treatment group were similar to those of a non-drug-exposed control group.

The Mom Empowerment Too (ME2) program combined community-based nursing and drug treatment through a participatory action research model for a young adult population. Participatory action research allowed researchers to collect outcome data while modifying aspects of the intervention in response to the feedback of the participants.143 Public health nurses used a variety of treatment modalities to provide case management services; access to drug treatment, medical care, and social services; educational and parenting classes; group therapy; and life skills training. The children (from birth to age 5 years) took part in developmental and health-promoting exercises while their parents attended their sessions. The investigators documented improvements in taking responsibility and learning to trust. Both areas of improvement are related to effective parenting.

In summary, intrauterine tobacco and illicit drug exposure are associated with adverse infant health outcomes. Studies suggest that infants exposed to these substances are at risk for attention and behavioral deficits during childhood. Data suggest that nicotine exposure places the child at risk for poorer cognitive outcome. Data concerning the causal associations between illicit drug exposure and cognitive outcome are less conclusive. More research is necessary to develop comprehensive prevention and intervention programs for this vulnerable population.

1 Office of Applied Studies. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health Report: Pregnancy and Substance Abuse. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004.

2 Office of Applied Studies: Results from the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (DHHS Publication No. SMA 05–4062, NSDUH Series H-28). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005. (Available at: http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/p0000016.htm#2k4; accessed 1/23/06.)

3 Office of Applied Studies. Illicit Drug Use in the Past Month among Females Aged 15 to 44, by Pregnancy Status and Demographic Characteristics: Percentages, 2002. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2002.

4 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2004.

5 DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Rigotti NA, et al. Development of symptoms of tobacco dependence in youths: 30 month follow up data from the DANDY study. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:228-235.

6 MMWR, Use of Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Among Students Aged 13–15 Years-Worldwide, 1999–2005, 55(20):553–556, May 26, 2006.

7 Henningfield J. Nicotine medications for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(18):1196-1202.

8 Moolchan E, Ernst M, Henningfield J, et al. A review of tobacco smoking in adolescents: Treatment implications. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(6):682-693.

9 Law KL, Stroud LR, Lagasse LL, et al. Smoking during pregnancy and newborn neurobehavior. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1318-1323.

10 Acute myocardial infarction and combined oral contraceptives. Results of an international multicentre case-control study. WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Lancet. 1997;349:1202-1209.

11 Fiore M, Bailey W, Cohen S, et al. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: A US P ubl ic Health Ser vice Report. JA M A. 2000;283(24):324. 4–3254

12 Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings, 2004(N I H Publication No. 05–5726). Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2005.

13 Smothers BA, Yahr HT, Ruhl CE. Detection of Alcohol Use Disorders in General Hospital Admissions in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:749-756.

14 Bonnie RJ, O’Connell ME, editors. Committee on Developing a Strategy to Reduce and Prevent Underage Drinking, Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, National Research Council, Institute of Medicine: Reducing Underage Drinking, A Collective Responsibility. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003.

15 Goodwin DW, Schulsinger F, Hermansen L, et al. Alcohol problems in adoptees raised apart from alcoholic biological parents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973;28:238-243.

16 Goodwin DW, Schulsinger F, Knop J, et al. Alcoholism and depression in adopted-out daughters of alcoholics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34:751-755.

17 Bohman M. Some genetic aspects of alcoholism and criminality: A population of adoptees. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:269-276.

18 Cloninger CR, Bohman M, Sigvardsson S. Inheritance of alcohol abuse: Cross fostering analysis of adopted men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:861-868.

19 Grant BF. Estimates of US children exposed to alcohol abuse and dependence in the family. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:112-115.

20 Wilens TE, Biederman J, Kiely K, et al. Pilot study of behavioral and emotional disturbances in the high-risk children of parents with opioid dependence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(6):779-785.

21 Stanger C, Higgins ST, Bickel WK, et al. Behavioral and emotional problems among children of cocaine-and opiate-dependent parents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:421-428.

22 Clark DB, Pollock N, Bukstein OG, et al. Gender and comorbid psychopathology in adolescents with alcohol dependence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1195-1203.

23 Merikangas KR, Stolar M, Stevens DE, et al. Familial transmission of substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:973-979.

24 Nunes EV, Weissman MM, Goldstein RB, et al. Psychopathology in children of parents with opiate dependence and/or major depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:1142-1151.

25 Chilcoat HD, Anthony JC. Impact of parent monitoring on initiation of drug use through late childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:91-100.

26 Stronski SM, Ireland M, Michaud PA, et al. Protective correlates of stages in adolescent substance use: A Swiss national study. J Adolesc Health. 2000;26:420-427.

27 Adger HJr, Macdonald DI, Wenger S. Core competencies for involvement of health care providers in the care of children and adolescents in families affected by substance abuse. Pediatrics. 1999;103(5, pt 2):1083-1084.

28 Harford TC. Family history of alcoholism in the United States: Prevalence and demographic characteristics. Br J Addict. 1992;87:931-935.

29 Bijur PE, Kurzon M, Overpeck MD, et al. Parental alcohol use, problem drinking, and children’s injuries. JAMA. 1992;267:3166-3171.

30 Murphy JM, Jellinek M, Quinn QD, et al. Substance abuse and serious child maltreatment: Prevalence, risk, and outcome in a court sample. Child Abuse Negl. 1991;15:197-211.

31 Greer SW, Bauchner H, Zuckerman B. Pediatricians’ knowledge and practices regarding parental use of alcohol. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:1234-1237.

32 Duggan AK, Adger H, McDonald EM, et al. Detection of alcoholism in hospitalized children and their families. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145:613-617.

33 Graham AV, Zyzanski S, Reeb K, et al. Physician documentation of family alcohol problems. J Subst Abuse. 1994;6:95-103.

34 Lazare A, Putnam S, Lipkin M. Functions of the medical interview. In: Lipkin M, Putnam S, Lazare A, editors. The Medical Interview: Clinical Care, Education, and Research. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1995:3-19.

35 Cohen-Cole SA. The Medical Interview: The Three Function Approach. St Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1991.

36 Hall JA, Roter DL, Rand CS. Communication of affect between patient and physician. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22:18-30.

37 Ewing JE. Detecting alcoholism: The CAGE questionnaire. JA M A. 1984;252:1905-1907.

38 Bush B. Screening for alcohol abuse using the CAGE questionnaire. Am J Med. 1987;82:231-235.

39 King M. At risk drinking among general practice attenders: Validation of the CAGE questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1986;16:213-217.

40 Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. Addiction. 1993;88:791-804.

41 Hops H, Tildesley E, Lichtenstein E, et al. Parent-adolescent problem solving interactions and drug use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1990;16:239-258.

42 Denoff MS. An integrated analysis of the contribution made by irrational beliefs and parental interaction to adolescent drug abuse. Int J Addict. 1988;23:655-669.

43 Wolin SJ, Bennett LA, Noonan DL, et al. Disrupted family rituals: A factor in the intergenerational transmission of alcoholism. Stud Alcohol. 1980;41:199-214.

44 Kandel DB, Andrews K. Processes of adolescent socialization by parents and peers. Int J Addict. 1987;22:319-342.