6

The ECG in Patients with Chest Pain or Breathlessness

Chest pain is a very common complaint, and when reviewing the ECG of a patient with chest pain it is essential to remember that there are causes other than myocardial ischaemia ( Box 6.1).

There are a few features of chest pain that make the diagnosis obvious. Chest pain that radiates to the teeth or jaw is probably cardiac in origin; pain that is worse on inspiration is either pleuritic or due to pericarditis; and pain in the back may be due to either myocardial ischaemia or aortic dissection. The ECG will help to differentiate these causes of pain but it is not infallible – for example, if an aortic dissection affects the coronary artery ostia, it can cause myocardial ischaemia.

THE ECG IN PATIENTS WITH CONSTANT CHEST PAIN

THE ECG IN ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

If a patient has chest pain and there is ECG evidence of myocardial ischaemia but a normal plasma troponin level, then the diagnosis is acute coronary syndrome due to unstable angina. Myocardial necrosis causes a rise in the level of plasma troponin (either troponin T or troponin I), and a high-sensitivity assay can detect a very small rise. By some definitions, any such rise in a clinical situation suggesting myocardial ischaemia justifies a diagnosis of myocardial infarction. However, the plasma troponin level may also rise in other conditions, which may also be associated with chest pain ( Box 6.2). It is essential to remember that the plasma troponin level may not rise for up to 12 h after the onset of chest pain due to a myocardial infarction.

Thus the ECG is an essential tool in the diagnosis of an acute coronary syndrome. Importantly, it also distinguishes between two categories of myocardial infarction whose management is different. The first is infarction associated with ST segment elevation, known as ‘ST segment elevation myocardial infarction’ or ‘STEMI’, and the second is ‘non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction’ or ‘NSTEMI’. Differentiation is important because a STEMI requires immediate treatment by thrombolysis or percutaneous intervention (PCI – i.e. angioplasty and probably stenting), although after 6 h the benefit of this treatment is largely lost. An NSTEMI may also require PCI but with considerably less urgency, and the patient is initially treated with some form of heparin, anti-platelet agents and a beta-blocker.

UNSTABLE ANGINA

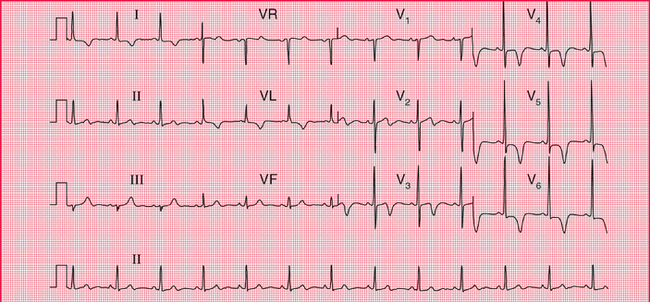

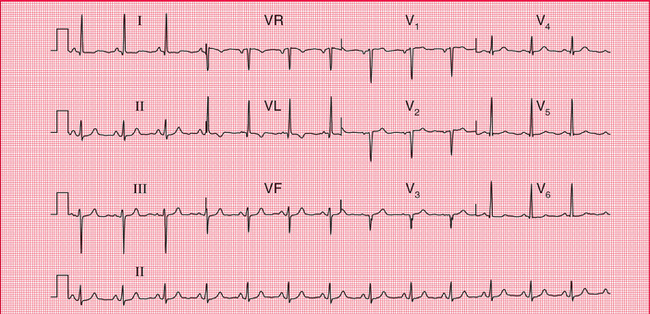

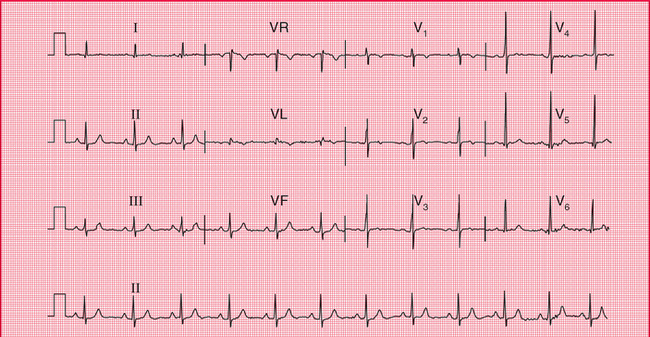

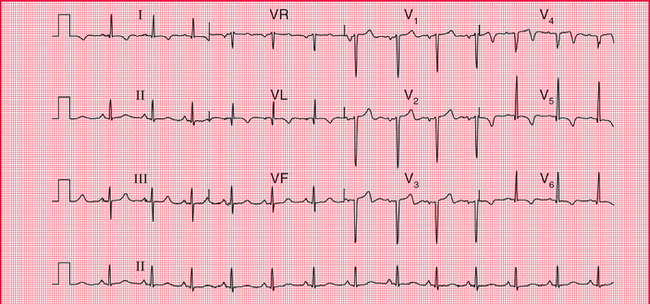

In unstable angina there is ST segment depression while the patient has pain ( Fig. 6.1). Once the pain has resolved the ECG returns to normal, or to its previous state if the patient has had a myocardial infarction in the past.

STEMI

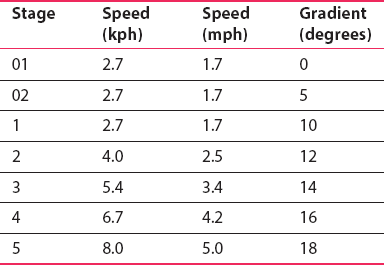

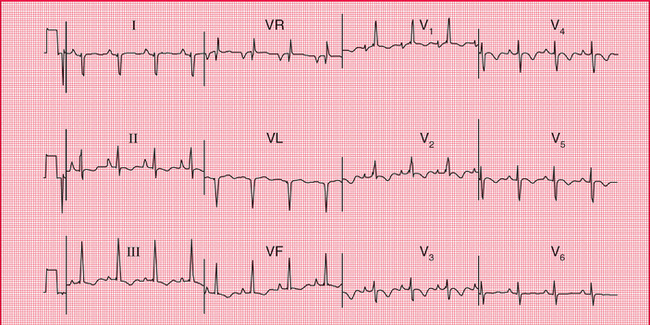

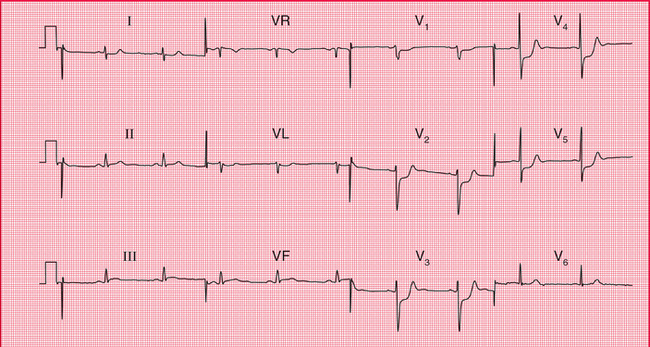

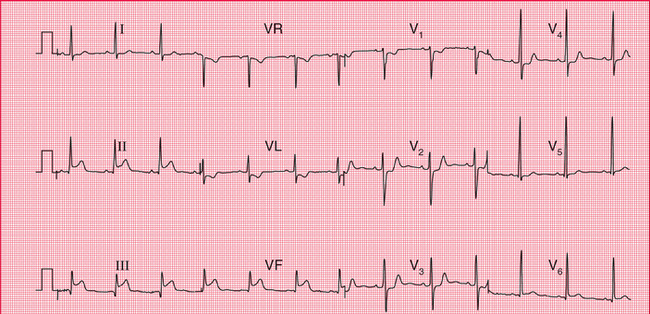

Figures 6.2–6.5 show ECGs from different patients with anterior infarctions, at increasing times from the onset of symptoms.

An old anterior infarction can also be diagnosed from an ECG that shows a loss of R wave development in the anterior leads without the presence of Q waves ( Fig. 6.6). These changes must be differentiated from those due to chronic lung disease, in which the characteristic change is a persistent S wave in lead V6. This is sometimes called ‘clockwise rotation’ because the heart has rotated so that the right ventricle occupies more of the precordium, and seen from below the rotation is clockwise ( Fig. 6.7).

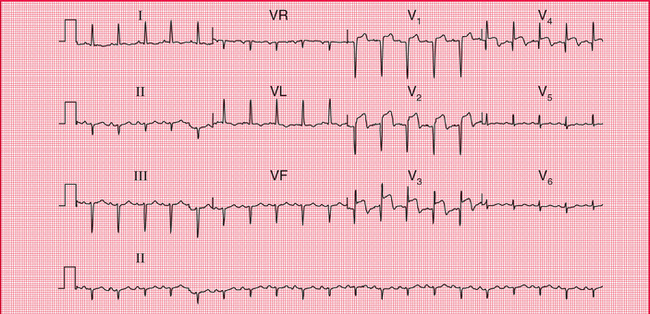

Fig. 6.3 ST segment elevation and Q waves in acute anterior ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

Note

Fig. 6.4 ST segment elevation and marked Q waves in acute anterior ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

Note

Fig. 6.6 Old anterior myocardial infarction with poor R wave progression in the anterior leads

Note

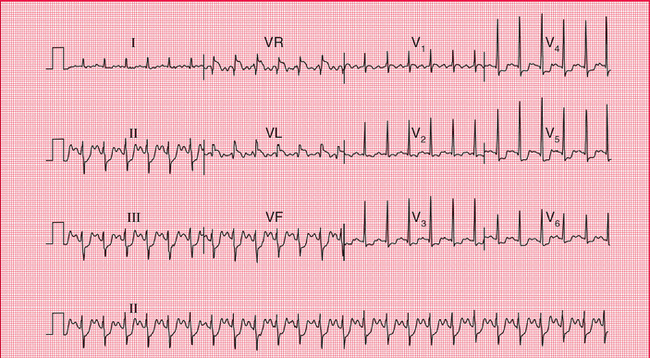

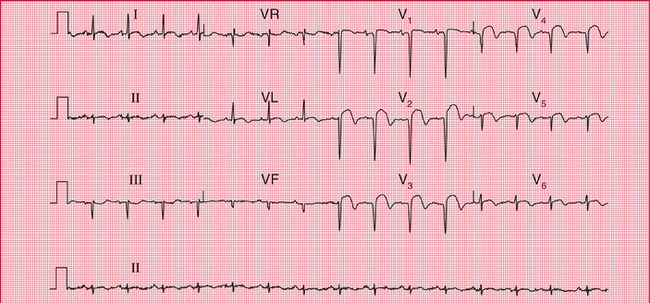

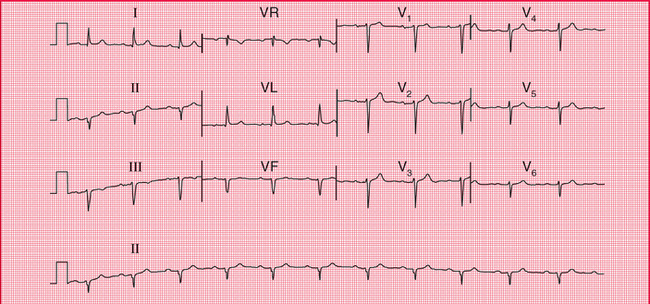

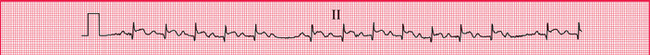

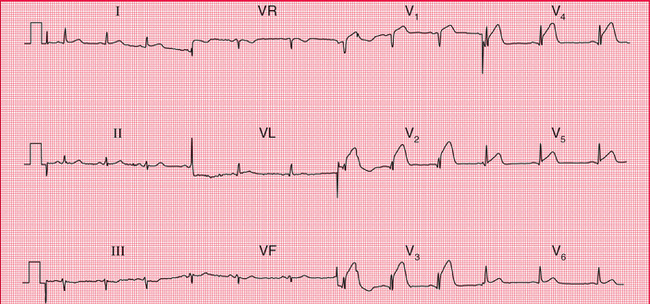

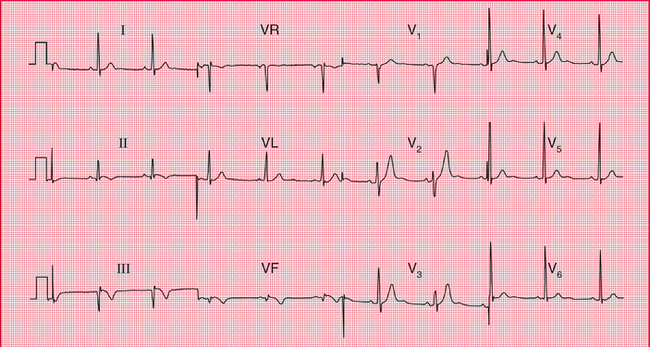

Figures 6.8–6.10 are ECGs from a patient recorded a few hours after the onset of chest pain and a few days later, and they show the patterns of inferior infarction. Figure 6.8 shows a classic inferior STEMI, with, in addition, T wave inversion in lead VL. A few days later ( Fig. 6.9), Q waves have appeared in leads III and VF, the ST segments have reverted almost to the baseline, and the T wave in lead VL is no longer inverted. During the acute phase of an inferior STEMI, conduction disturbances are quite common, as exemplified by the second degree block in Figure 6.10, showing the rhythm strip of an ECG recorded a few hours after that shown in Figure 6.8.

Fig. 6.10 Second degree (Wenckebach) heart block in inferior myocardial infarction (same patient as in Fig. 6.8)

Note

When an infarction develops in the posterior wall of the left ventricle, Q waves can only be elicited by placing the chest lead on the patient′s back. In a routine ECG there will be a dominant R wave in lead V1, caused by unopposed anterior depolarization ( Fig. 6.11.)

NSTEMI

In NSTEMI there is no ST segment elevation, but there is T wave inversion in the leads corresponding to the site of myocardial damage ( Fig. 6.12). With time the T waves may revert to normal, but inversion may persist. Q waves do not develop, and for this reason a distinction used to be made between ‘Q wave’ and ‘non-Q wave’ infarction. On the whole, Q-wave infarctions are STEMIs and non-Q wave infarctions are NSTEMIs. However, there is now treatment (PCI or thrombolysis) that can prevent Q wave development in a STEMI, making the Q/non-Q differentiation redundant.

THE ECG IN PATIENTS WITH INTERMITTENT CHEST PAIN

Patients with angina may have a normal ECG when they are pain-free, although frequently the ECG shows evidence of a previous infarction. Patients whose chest pain is due to oesophageal disease or to muscular disorders, or whose pain is ‘nonspecific’, will also have a normal ECG.

For more on exercise testing see pp. 270-284

For more on exercise testing see pp. 270-284

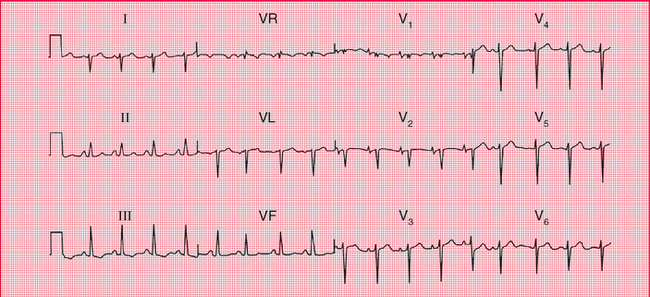

Exercise testing can be performed on a treadmill or an exercise bicycle, the former being more commonly used in the UK. After recording the ECG at rest, exercise is rcise testing, progressively increased in stages of 3 min. The pp. 270–284 most commonly used protocol is that devised by Bruce ( Table 6.1). The two low-level stages (the 144 ‘modified Bruce protocol’), both at 2.7 kph but with a 0% or 5% gradient, can be used when a patient′s exercise tolerance is markedly limited.

A diagnosis of cardiac ischaemia can confidently be made if there is horizontal ST segment depression of at least 2 mm. If the ST segments are depressed but upward-sloping, there is probably no ischaemia. Figures 6.13 and 6.14 show the ECG of a patient at rest and after exercise causing angina.

THE ECG IN PATIENTS WITH BREATHLESSNESS

Some causes of breathlessness are summarized in Box 6.3.

BREATHLESSNESS DUE TO HEART DISEASE

REMINDERS

CARDIAC HYPERTROPHY

Right atrial hypertrophy

Right ventricular hypertrophy

Left atrial hypertrophy

Left ventricular hypertrophy

BREATHLESSNESS DUE TO LUNG DISEASE

Pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism often presents as a combination of chest pain and breathlessness. Although the chest pain is characteristically one-sided and pleuritic, a major embolus affecting the main pulmonary arteries may cause pain resembling that of myocardial infarction. Patients with pulmonary hypertension usually complain of breathlessness but not pain.

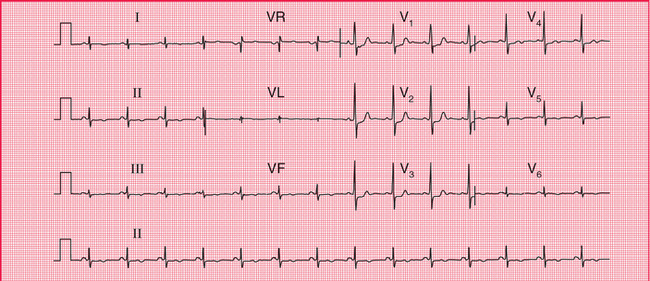

With pulmonary embolism the most common ECG finding is sinus tachycardia with no other abnormality ( Fig. 6.15), so the ECG is not a very useful diagnostic tool. However, the appearance of right bundle branch block, or the changes associated with right ventricular hypertrophy (right axis deviation, a dominant R wave in lead V1, and T wave inversion in leads V1-V3) would strongly support the diagnosis. If the patient develops permanent pulmonary hypertension, the full ECG picture of right ventricular hypertrophy will persist.

For more on pulmonary embolism, see pp. 247-250

For more on pulmonary embolism, see pp. 247-250

The commonly quoted ‘S1Q3T3’ pattern (i.e. right axis deviation with a prominent S wave in lead I and a Q wave and an inverted T wave in lead III) is seen in Figure 6.15, and is commonly quoted as an indicator of pulmonary embolism. In practice, it is not a very reliable indicator unless it is seen to appear in repeated recordings.

Chronic lung disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary fibrosis and other intrinsic lung diseases do not usually cause the ECG changes associated with severe pulmonary hypertension, but there may be right axis deviation and, more often, clockwise rotation of the heart ( Fig. 6.16). This is because the heart is rotated, with the right ventricle occupying more of the precordium than usual.

For more on STEMI, see pp. 214-240

For more on STEMI, see pp. 214-240