Chapter 13 The eyes, ears, nose and throat

The eyes

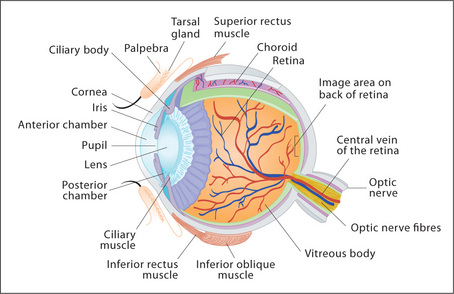

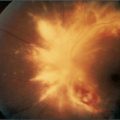

Examination anatomy (Figure 13.1)

The structure of the eye is shown in Figure 13.1. Many of these structures can be examined as outlined below.

Examination method

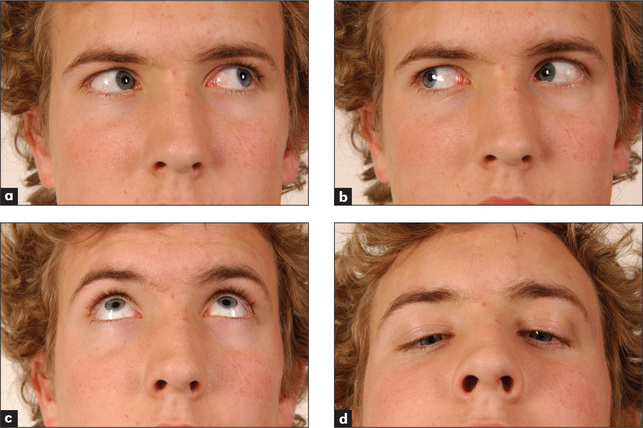

Figure 13.4 The cranial nerves III, IV & VI: voluntary eye movements

(a) ‘Look to the left.’ (b) ‘Look to the right.’ (c) ‘Look up.’ (d) ‘Look down.’

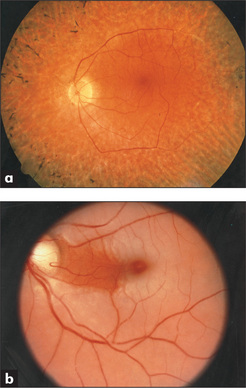

Examine the retinas (Figure 13.5; see also Figure 11.8, page 336). Focus on one of the retinal arteries and follow it into the optic disc. The normal disc is round and paler than the surrounding retina. The margin of the disc is usually sharply outlined but will appear blurred if there is papilloedema or papillitis, or pale if there is optic atrophy. Look at the rest of the retina, especially for the retinal changes of diabetes mellitus or hypertension.

There are two main types of retinal change in diabetes mellitus: non-proliferative and proliferative. Non-proliferative changes include: (1) two types of haemorrhages—dot haemorrhages, which occur in the inner retinal layers, and blot haemorrhages, which are larger and occur more superficially in the nerve fibre layer; (2) microaneurysms (tiny bulges in the vessel wall), which are due to vessel wall damage; and (3) two types of exudates—hard exudates, which have straight edges and are due to leakage of protein from damaged arteriolar walls, and soft exudates (cottonwool spots), which have a fluffy appearance and are due to microinfarcts. Proliferative changes include new vessel formation, which can lead to retinal detachment or vitreous haemorrhage.

Hypertensive changes can be classified from grades 1 to 4:

It is important to describe the changes present rather than just give a grade.

The causes of common eye abnormalities are summarised in Table 13.3.

| Cataracts |

CSF = cerebrospinal fluid.

* Sigvald Refsum, 20th century Norwegian physician.

† Theodor von Leber (1840–1917), Göttingen and Heidelberg ophthalmologist.

‡ John Laurence (1830–1874), London ophthalmologist; Robert Charles Moon (1844–1914), American ophthalmologist; and Arthur Biedl (1869–1933), professor of physiology, Prague.

Diplopia

If the diplopia is binocular, consider the common causes:

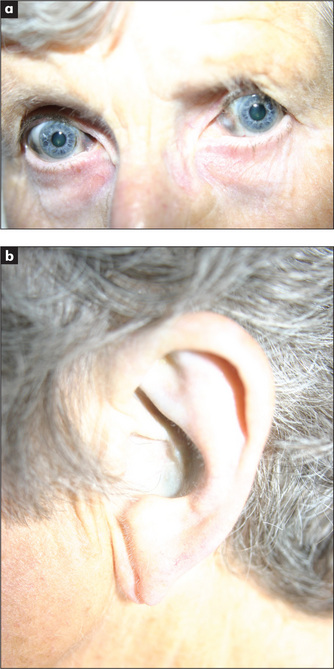

Horner’s syndrome

* Sweating unaffected, as tumour localised to internal carotid artery.

Clinical approach

The syndrome includes partial ptosis (as sympathetic fibres supply the smooth muscle of both eyelids) and a constricted pupil (unbalanced parasympathetic action) which reacts normally to light (Figure 13.6). Remember the other causes of ptosis (Table 13.5).

| Cause | Associated features |

| Age-related stretching of levator muscle or aponeurosis | Common, often asymmetrical |

| Orbital tumour or inflammation | Orbital abnormality |

| Horner’s syndrome | Constricted pupil, reduced sweating |

| Third nerve palsy | Eye ‘down and out’, dilated pupil |

| Myasthenia gravis or dystrophical myotonica | Extraocular muscle palsies, muscle weakness |

| Congenital or idiopathic |

Test for a difference (decrease) in the sweating over each eyebrow with the back of the finger (absence of this sign does not exclude the diagnosis).b

Horner’s syndrome may be part of the lateral medullary syndrome.c

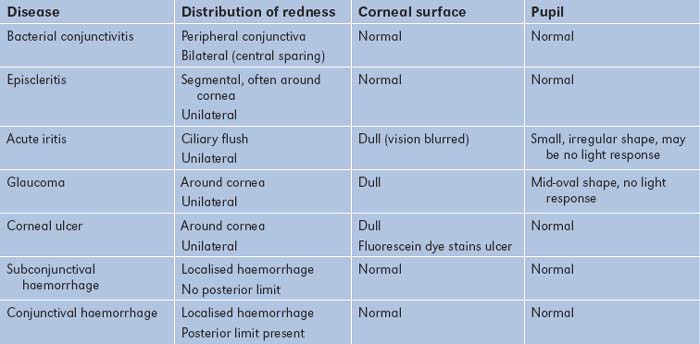

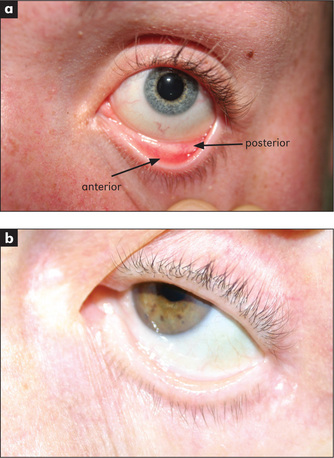

Iritis

Iritis (anterior uveitis) presents with pain, photophobia and unilateral eye redness (Tables 13.1 and 13.2). On examination of the eye, there is classically a ciliary flush with dilated vessels around the iris. Hypopyon refers to pus in the anterior chamber; a fluid level may be seen. The pupil is usually irregular. There may also be new vessel formation over the iris.

Shingles

Herpes zoster involving the first (ophthalmic) division of the trigeminal nerve may result in uveitis and keratitis, and threaten vision. The tip of the nose, cornea and iris are all innervated by the nasociliary nerve (a branch of the trigeminal nerve). The appearance of vesicles on the tip of the nose (Hutchinson’sd vesicles) in patient with herpes zoster indicates an increased risk of ophthalmic complication (LR 3.5).1

Eyelid

Two conditions of the eyelid are worth remembering:

The ears

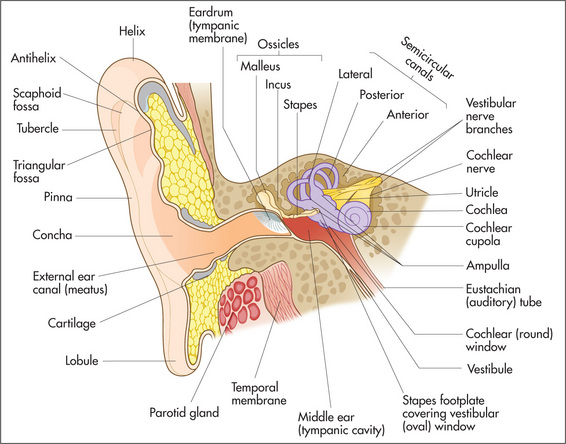

Examination anatomy

The pinna, external auditory canal and ear drum are easily assessed with simple equipment (Figure 13.9). Tests of hearing can also provide information about the severity and anatomical site of hearing loss.

Examination method

Ear examination consists of inspection and palpation, auriscopic examination and testing hearing.

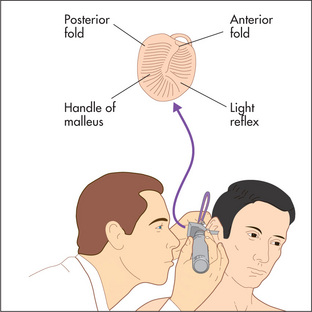

Auriscopic examination of the ears requires use of an earpiece that fits comfortably in the ear canal to allow inspection of the ear canal and tympanic membrane (Figure 13.10). This examination is essential if there is a history of recent deafness or a painful ear. Examination is also necessary in the patient who has had a head injury. Always examine both ears!

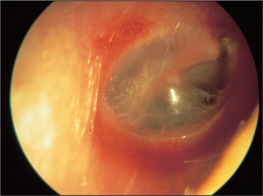

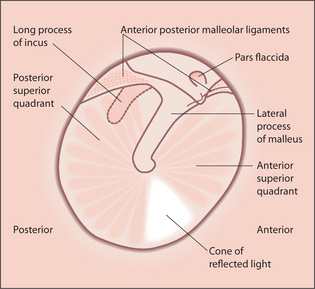

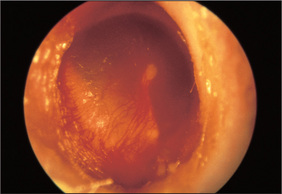

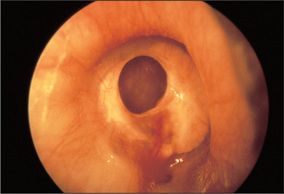

Inspect the tympanic membrane (ear drum) by introducing the speculum further into the canal in a forward but downward direction. The normal tympanic membrane is greyish and reflects light from the centre at approximately 5 or 7 o’clock (Figures 13.11 and 13.12). Note the colour, transparency and any evidence of dilated blood vessels (hyperaemia—a sign of otitis media) (Figure 13.13). Look for bulging or retraction of the tympanic membrane. Bulging can suggest underlying fluid or pus in the middle ear. Perforation of the tympanic membrane should be noted (Figure 13.14).

Figure 13.11 The tympanic membrane as viewed through an otoscope

From Mir MA, Atlas of Clinical Diagnosis, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Saunders, 2003, with permission.

Figure 13.12 The detail of the tympanic membrane

From Mir MA, Atlas of Clinical Diagnosis, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Saunders, 2003, with permission.

Figure 13.13 Otitis media with hyperaemia of the tympanic membrane

From Mir MA, Atlas of Clinical Diagnosis, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Saunders, 2003, with permission.

Figure 13.14 Perforated tympanic membrane

From Mir MA, Atlas of Clinical Diagnosis, 2nd edn.Edinburgh: Saunders, 2003, with permission.

If a middle ear infection is suspected, pneumatic auriscopy can be useful. Use a speculum large enough to occlude the external canal snugly. Attach a rubber squeeze bulb to the otoscope. When the bulb is squeezed gently, air pressure in the canal is increased and the tympanic membrane should move promptly inward. Absence of, or a decrease in, movement is a sign of fluid in the middle ear.

To test hearing, whisper numbers 60 cm away from one of the patient’s ears while the other ear is distracted by movement of the examiner’s finger in the auditory canal. Then repeat the process with the other ear. With practice the normal range of hearing is appreciated. Next perform Rinné’s and Weber’s tests (page 347):

The nose

Examination method

Nose examination consists of inspection, palpation and testing the sense of smell.

Palpate the nasal bones. Then feel for facial swelling or signs of inflammation. Block each nostril to assess any obstruction by asking the patient to inhale. If there is a history of anosmia (loss of smell), test smell as described in Chapter 11 (cranial nerve I).

The throat

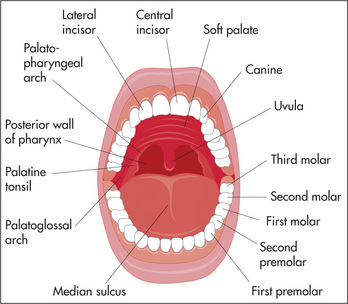

Examination method

Throat examination consists of inspection and palpation.

Palpate the tongue for lumps (wear gloves). Palpate the salivary glands. Examine the cervical lymph nodes.

Pharyngitis

Clinical criteria are available for determining whether the pharyngitis is likely due to beta-haemolytic streptococcus or not. The absence of cough, along with a history of fever, presence of a pharyngeal exudate on examination and anterior cervical adenopathy together strongly predict the presence of this infection, while the absence of the last three strongly suggests that the infection is not due to beta-haemolytic streptococcus. It is important to recognize this because beta-haemolytic streptococcus infection of the pharynx can lead to direct infectious complications (otitis media, sinusitis, peritonsillar abscess [quinsy] and submandibular space infection [Ludwig’se angina]) and to indirect complications (acute rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis). Glomerulonephritis is not prevented by antibiotic therapy.

a Johann Friedrich Horner (1831–1886), professor of ophthalmology, Zürich, described this in 1869.

b Enophthalmos or retraction of the eye, which is often mentioned as a feature of Horner’s syndrome, probably does not occur in humans. It may occur in cats. Horner’s original paper was very specific about miosis and ptosis, but only casually mentioned that ‘the position of the eye seemed very slightly inward’. Apparent enophthalmos results from a combination of ptosis and an elevated lower lid (upside-down ptosis).

c Occlusion of any of the following vessels may result in this syndrome: vertebral; posterior inferior cerebellar; superior, middle or inferior lateral medullary arteries.

d Sir Jonathon Hutchinson (1828–1913). Among other appointments he was surgeon to Moorfields Eye Hospital. He was president of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1889, elected to the Royal Society in 1882 and knighted in 1908.

e Wilhelm Ludwig (1790–1865) was an army surgeon during the Napoleonic wars and a Russian prisoner of war for 2 years. He became court doctor to King Frederick II and was professor of surgery and midwifery at Tübingen. He described submandibular cellulitis in his first paper, published 20 years after he became a professor. The patient described was Queen Catherine of Würtenberg.